CHAPTER 21

Supply/Demand Imbalance

Prostate cancer is the most common form of cancer in men. With the exception of lung cancer, it kills more men than any other form of cancer. According to a paper published in the World Journal of Oncology, in 2018 alone, 1.3 million men were diagnosed with prostate cancer and 359,000 died.1

Metastatic prostate cancer is prostate cancer that has spread to other organs such as the lymph nodes, bones, lungs, or liver. While prostate cancer survival rates have improved dramatically over the last couple of decades, especially in developed countries, metastatic prostate cancer is more serious and has a lower survival rate.

Given the high incidence of prostate cancer, and in particular the dangers associated with metastatic prostate cancer, this area has been viewed as a large market opportunity for any pharmaceutical company that could develop a drug to treat patients burdened by this disease. Medivation had such a drug.

MEDIVATION’S STORY

In 2012, Medivation, a midsized pharmaceutical firm, received approval for Xtandi, a drug used to treat post-chemotherapy prostate cancer patients. Two years later, Medivation received a label expansion that allowed Xtandi to be used prior to chemotherapy.

In the pre-chemotherapy setting, a patient was likely to be on the drug longer than in the post-chemotherapy setting. The number of potential patients was also much larger.

In the six months following the label expansion, Medivation’s stock rose from the mid-forties to the mid-sixties.

In addition to its indication for the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer, Medivation had multiple ongoing trials, including one that could extend Xtandi into non-metastatic and hormone-sensitive prostate cancers as well as advanced triple-negative breast cancer. If these trials were successful, they would expand the drug’s addressable market and increase its peak sales potential.

Xtandi competed against Zytiga from Johnson & Johnson and a generic drug called Casodex. Medivation’s patents on Xtandi were scheduled to last through 2026 in Europe and 2027 in the United States.

Medivation shared the economics of Xtandi with Astellas, a Japanese pharmaceutical company, as part of a 2009 agreement whereby Medivation would sell Xtandi in the United States and receive 50% of the revenues. Astellas was responsible for international sales and paid royalties on these ex-US sales to Medivation. Medivation had one drug in its pipeline: an earlier stage immuno-oncology agent called pidilizumab. It purchased another pipeline asset in 2015 from BioMarin called talazoparib that was in a phase 3 trial for BRCA-mutated breast cancer.

US Xtandi sales had risen rapidly from $57 million in the fourth quarter of 2012 to $144 million in the second quarter of 2014, before any benefit from the new label expansion. With the expanded label, sales rose to $230 million in the fourth quarter of 2014. As a result of this explosive growth, by mid-2015, the sell-side analyst consensus estimates for 2019 US Xtandi revenues had risen to more than $3 billion.

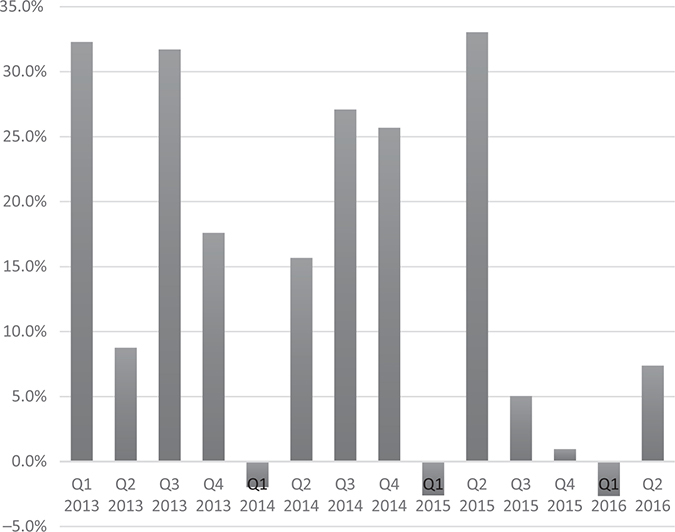

But beginning in the fall of 2015, something unexpected occurred. Prescription trends for Xtandi, which were anticipated to continue growing rapidly, didn’t. Xtandi’s US sales grew much more slowly than expected over the next three quarters, as shown in Figures 21.1 and 21.2. This slowdown would call into question the ultimate market opportunity for Xtandi. By February of 2016, Medivation shares had declined by 60% from their recent peak.

FIGURE 21.1

US Xtandi Sales2

FIGURE 21.2

US Xtandi Q/Q Sales Growth3

US Xtandi sales beat sell-side expectations almost every quarter between the first quarter of 2012 and the fourth quarter of 2014. However, US Xtandi sales would go on to miss sell-side consensus expectations four out of the next six quarters, between the first quarter of 2015 and second quarter of 2016.

Why were US Xtandi revenues stalling out?

• Xtandi vs. Zytiga: Xtandi was more expensive than Johnson & Johnson’s Zytiga, which made it difficult to gain market share.

• Urologists: Medivation struggled to persuade enough urologists to prescribe Xtandi over other alternatives.

In addition, there were other concerns about Xtandi that weighed on Medivation’s stock price:

• Generic Zytiga: There was some concern about the future competitive environment. Johnson & Johnson’s patent protection on Zytiga was expected to expire in 2018 or 2019, which could facilitate the introduction of a low-cost generic version onto the market. A much lower-cost alternative to Xtandi could have a negative impact on Xtandi’s market share. If Xtandi was already struggling to gain significant market share from Zytiga, what would happen in the future when a low-cost generic version of Zytiga was available?

• New competition: Both Johnson & Johnson and Bayer were running phase 3 trials for new drugs to treat prostate cancer. If either of these drugs were superior to Xtandi with respect to efficacy, side effects, or both, they could limit Xtandi’s sales potential or cause revenues to decline.

However, fundamentals would soon take a backseat to the prospect of Medivation being acquired.

MEDIVATION TAKEOVER BATTLE TIMELINE

Takeover battles often move quickly and dramatically. The Medivation takeover was no exception and involved multiple players and multiple bids.

• On March 22, 2016, Olivier Brandicourt, the CEO of Sanofi, a French pharmaceutical company that was struggling with declines in its diabetes franchise, contacted Medivation’s CEO David Hung, MD. Sanofi was interested in buying Medivation, which set off a fierce takeover battle for control of Medivation and its cancer drug.

• On March 24, Medivation’s board responded by hiring JP Morgan as an advisor.

• In late March, the press got wind of Sanofi’s interest in Medivation and the fact that Medivation had hired bankers.

• On April 3, Dr. Hung informed Olivier Brandicourt that Medivation was not interested in discussing a potential sale of the company.

• On April 15, Sanofi offered to buy Medivation for $52.50, subject to future due diligence. This offer was not disclosed publicly at the time.

• On April 20, an executive from Pfizer reached out to Dr. Hung to say that Pfizer would like to be included in any strategic review process that Medivation would undertake. In other words, if Medivation chose to sell, Pfizer wanted a seat at the bidding table.

• On April 28, Sanofi publicly announced its $52.50 bid for Medivation.

• On April 29, Medivation announced that its board of directors had rejected Sanofi’s bid.

• On May 5, Sanofi went hostile. Sanofi threatened to “remove and replace” the board of Medivation if it did not engage with Sanofi concerning its takeover bid. After the stock market close on May 5th, Medivation reported Xtandi’s US sales were $308 million in the quarter. This represented a quarter-over-quarter decline of 3%. It was 7 points below consensus expectations and reflected the third consecutive quarter of lower than anticipated sales for Medivation’s only approved drug. Xtandi had effectively stopped growing. In addition, Medivation missed consensus EPS expectations by 50%. But Sanofi kept coming.

• On May 25, Sanofi followed through with its threat to start a process that could lead to the removal of Medivation’s eight board members and their replacement by directors selected by Sanofi.

• On June 21–22, the Medivation board reversed course and began a process that would eventually lead to the sale of the company. The board directed its bankers to determine who might have an interest in acquiring Medivation and what they would be willing to pay.

• In late June, Medivation and its bankers contacted 12 companies, including Pfizer and 4 others that had expressed interest after the press reported on Sanofi’s interest.

• On June 27, Sanofi offered $58 per share along with a $3 contingent value right (CVR), dependent on the achievement of various future revenue targets. A CVR should be thought of as an option. If a company hits a revenue target or if a future clinical trial outcome is positive, the holder of the CVR can receive up to the face value of the CVR (in this case $3). Following an acquisition, a CVR will trade like a stock or an option in the open market until the revenue target is met or missed, or the clinical trial succeeds or fails.

• On June 30, Medivation once again rejected the Sanofi bid. However, the board also invited Sanofi to join in the strategic review process.

• Between July 7 and July 13, Medivation entered into confidential agreements with five potential acquirers, which provided them access to nonpublic information and allowed them to perform due diligence on Medivation.

• From July 15 to 21, the management team of Medivation gave a series of in-person presentations to each of the potential bidders.

• On July 19–20, Medivation’s bankers asked for preliminary bids by August 8 from the five parties.

• On August 3, CVS Health announced that Xtandi would be one of 29 drugs that would be excluded from its 2017 formulary. This action would make it more difficult for CVS Health’s tens of millions of pharmacy benefit members to receive Xtandi for the treatment of prostate cancer. Did this impact the bidding? Nope.

• On August 8, Pfizer bid $65 in cash for Medivation. Two other firms offered purely cash deals, one for $71 and another for $62–$64. Two other firms offered cash plus contingent value rights, one for $60 in cash and a $10 CVR and another for $63 and a $5 CVR.

• On August 9, Medivation reported that US Xtandi sales once again missed consensus estimates.

• On August 10, Medivation’s board planned to reduce the bidders from five to three. However, the next day, the two firms that had been told their bids were not high enough revised them to $70 and $70.50 in cash.

• On August 14, Medivation bankers asked for definitive proposals from the five remaining bidders.

• On August 19, four of the five firms submitted bids with Pfizer at $77 and the other three at $72.50, $73, and $75.50. On that same day, the four bidders were told to send in their final and best offer. That night, one of the four remaining decided that it would not increase its bid.

• On August 20, Pfizer bid $81.50 and the two other companies offered $80.25 and $80. All the bids were in cash and there were no CVRs. On that same day Medivation’s board accepted the Pfizer bid and publicly announced its decision.

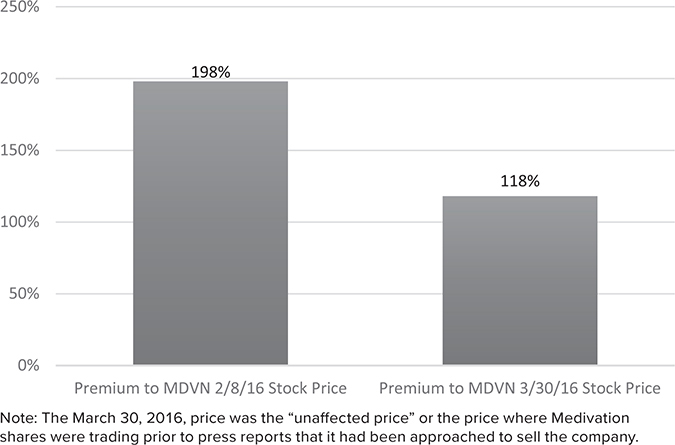

In the end, Pfizer won the takeover battle with a bid of $81.50, which valued Medivation at $14 billion on an enterprise value basis.

FIGURE 21.3

Pfizer Paid a Large Premium to Where Medivation Was Valued by the Market.

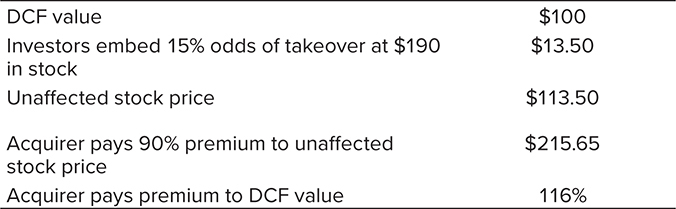

The Medivation management team provided its bankers with internal projections for sales, margins, and FCF through 2032. Medivation’s bankers used these inputs to create a discounted cash flow (DCF) valuation for Medivation’s shares under three scenarios, shown in Table 21.1.

TABLE 21.1

Scenarios for Medivation’s Performance4

Based on my reading of the proxy statement, all of these scenarios assumed different degrees of success for Xtandi in multiple new indications/therapies as well as the successful launch of its two pipeline products. It does not appear that Medivation’s bankers used additional inputs beyond management’s internal projections when creating these discounted cash flow (DCF) analyses.

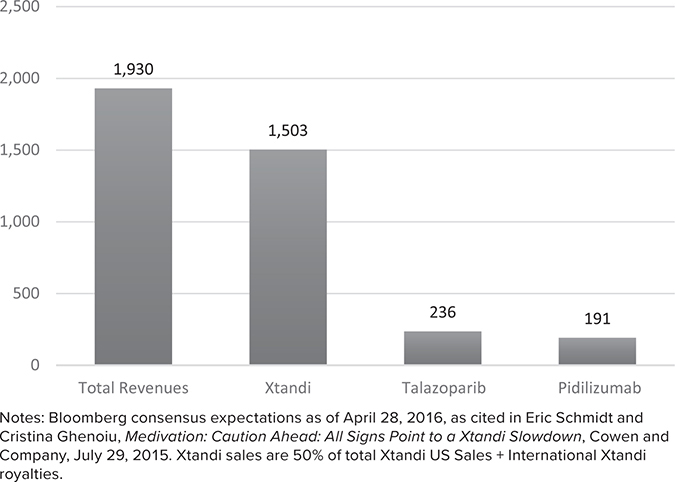

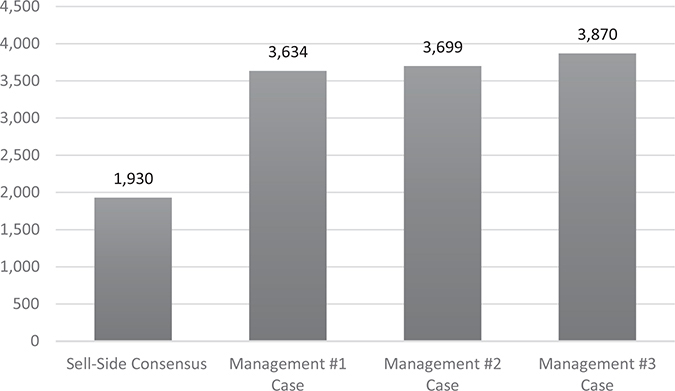

What I find fascinating about these management projections is that they are substantially higher than the consensus estimates from the sell-side analysts who covered Medivation. While most did not publish a 2027 estimate in 2016, their 2022 estimates indicate how aggressive these management assumptions appear. (See Figures 21.4, 21.5, and 21.6.)

FIGURE 21.4

Medivation’s 2022 Consensus Revenue Expectations5

FIGURE 21.5

2022 Medivation Revenue Expectations6

FIGURE 21.6

Management Revenue Projections Appear Aggressive (Percentage Premium Versus 2022 Consensus)7

Management estimates were not just a little bit higher than consensus, they were 88–101% higher than the consensus estimates for 2022. Extrapolating these industry-expert estimates out to 2027, it would be very easy to argue that the proxy’s DCF values were more than double what they would have been if the bankers had used sell-side industry analyst projections instead of management projections.

Another way to illustrate this point is to consider that Medivation’s 2016 revenue projections were $922 million according to the proxy. Scenario 2 (see Table 21.1) predicted revenues ramping up to $7.3 billion by 2027. That is a 21% annual growth rate for the next 11 years!

To be fair, it would be logical to assume that Pfizer’s cost of capital would be lower than Medivation’s. Thus, the Medivation portfolio would be worth more inside of Pfizer than as a stand-alone entity. If Medivation management’s far-above-consensus projections ended up being accurate, it is likely that the DCF value to Pfizer would be greater than the high end of the DCF value used in the three scenarios.

In addition, one might argue that I am ignoring the potential cost synergies that Pfizer might be able to wring out in this acquisition, which is a fair observation. However, the three scenarios already assumed extremely high operating margins in 2027 (79.5%, 79.7%, and 77.3% respectively). Pfizer’s operating margins in 2015 were 36.3%. Best-in-class biotech firms can sometimes achieve mid-fifties operating margins.

Even assuming a lower cost of capital and cost synergies from the transaction, it still appears that Pfizer paid a hefty price for Medivation that would require extraordinary sales growth, sky-high margins, success with Xtandi indication expansion, and future pipeline success to generate reasonable cash-on-cash returns for Pfizer.

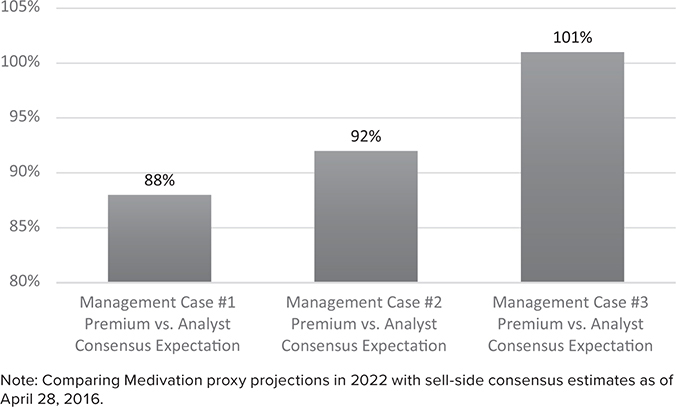

Why was Pfizer willing to pay a 118% premium (see Figure 21.3) to Medivation’s unaffected stock price and, more important, why were two other companies willing to pay almost the same price? Remember, this is not a situation in which Pfizer paid a massive premium to the other bidders. Pfizer and two other companies were all willing to pay essentially the same price.

The answer comes down to these firms’ desperation for a growing asset with intermediate-term patent protection in an attractive part of the pharmaceutical market. These types of assets can support a firm’s revenue growth and help overcome the headwinds associated with patent protection expirations.

Pfizer’s acquisition of Medivation highlights the challenge of engaging in M&A in a space where there is a supply/demand imbalance that heavily favors sellers. While this challenge is not limited to the pharmaceutical industry, it is most pronounced there, given past consolidation, structural industry changes, and the limited patent life of most pharmaceutical products.

BIG PHARMA’S QUEST FOR GROWTH

One of the challenges for big pharma and increasingly big biotech (Biogen, Abbvie, Amgen, Gilead) is the companies’ massive size, with each having more than $10 billion in revenues. Many large pharmaceutical companies such as Pfizer, Bristol-Myers, GSK, and Astra-Zeneca are products of large, mostly cost-driven mergers and, in some cases, multiple, large mergers. In addition, many are victims of their own success. They develop a drug with good clinical outcomes, such as Lipitor or Crestor to lower cholesterol, but then struggle to develop a new drug that is materially better once their innovative drug goes generic and the price drops dramatically.

In 2005, about 60% of drugs dispensed in the United States were generics. By 2018, 90% were. From a purely dispensing perspective, branded pharmaceuticals have lost 75% of their market share to generics over the last 13 years!8

As a result of mergers and past success in developing efficacious drugs, many of these companies have struggled to replace their massive revenue bases through organic, internal R&D. Pharma companies, unlike most other businesses, operate on a treadmill. If they fail to introduce new, innovative drugs that are safe and much more effective than low-cost generic alternatives, their business can literally vanish in a little more than a decade.

Today, the pharmaceutical industry faces two additional structural challenges.

The PBM Industry

The pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) industry has consolidated over the years, and its power and influence over drug pricing has become a thorn in the side of the pharmaceutical industry. Each of the large PBMs operates a formulary that functions like an “auction for volume” for a class of drugs that are not highly differentiated. In these cases, the PBM will provide a pharmaceutical company with increased market share in return for a big volume discount.

While the PBM’s clients can still access drugs that are not on the formulary, the consumer may have to pay higher out-of-pocket costs and/or the prescribing doctor may have to jump through multiple hoops.

In addition, new drugs that are only modestly better than the generic alternative struggle to gain acceptance because cost-benefit analysis does not justify their use. This issue is most pronounced in areas such as cholesterol and respiratory, which once generated multiple billions in revenues annually but have since seen a rise in the availability of highly efficacious generics. This has greatly diminished the ability of pharmaceutical companies to re-create large revenue drug franchises.

Biosimilars

There are two main kinds of drugs: small-molecule and large-molecule/biotech drugs. Small-molecule drugs are relatively easy for a generic company to manufacture. Once patent protection expires, pricing typically drops dramatically and the innovative pharmaceutical company’s revenues fall 90%+.

However, a large-molecule/biotech drug is much more difficult for a generic company to manufacture, and a branded biotech drug might be protected not only by patents on its chemical composition (like small-molecule drugs) but on its manufacturing process as well. The result is that many biotech drugs can continue to generate revenue well past the expiration of their original chemical composition patent.

Even when a generic company is able to manufacture a biotech drug, it often struggles to gain a regulatory pathway to market. To enter the market, they need to prove that it is producing exactly the same drug as the original. This often requires running multiple trials, which is costly and time-consuming. This ultimately results in less competition, and even when there are biosimilars available, the price of the drug tends to decline materially less than with a small-molecule generic.

However, this is changing. Europe has implemented an improved regulatory mechanism to enable lower-cost biosimilars to come to market, and a similar trend, although with a lag, is emerging in the United States. This only adds to the challenges for big pharma and big biotech as biosimilars put pressure on revenue streams previously thought to be protected from real competition.

THE CHALLENGES FACING BIG PHARMA AND BIG BIOTECH

Large pharmaceutical companies today find themselves with less pricing power than in the past, emerging competition for their biotech drugs, and limited opportunities to re-create large revenue streams in important therapeutic areas. As a result, they face the titanic challenge of trying to replace and grow their massive revenue base organically through internal R&D.

This has forced pharmaceutical firms to price innovative new drugs at higher price points to support their top line. Long term, this strategy could create a backlash from consumers and politicians that could curtail pharmaceutical firms’ pricing power.

Faced with these multiple challenges, many large pharma and large biotech companies have chosen to invest aggressively in oncology (cancer) R&D and also to invest inorganically in oncology acquisitions.

Cancer/oncology is one of the few remaining frontiers for pharmaceutical companies to invest in for several reasons:

• Cancer involves life or death, so price is less important. Annual costs of these drugs can now run in the hundreds of thousands or even millions of dollars per patient for some of the newest, most innovative drugs.

• Within the oncology space, there have been recent advances in immuno-oncology that, from a very high level, involve supercharging the body’s own immune system to fight cancer. This has opened up a whole new area for researchers to explore in the battle against cancer.

• Small innovations and mild improvements in expected survival periods can generate billions in incremental revenues for pharmaceutical companies. Modest improvements in other therapeutic areas struggle to gain widespread acceptance, given the aforementioned cost-benefit analysis and the power of PBMs.

• PBM power is more limited relative to other categories, although this did not stop CVS Health from excluding Xtandi from its formulary in 2017.

This has set off a mad dash for oncology assets with large pharma and large biotech paying increasingly high prices and valuation multiples. There is simply too much demand and too little supply. As a result, when a business like Medivation becomes available in the oncology space, just about everyone wants it and, in the end, the winning bidder is cursed with a poor return on capital.

But this is not limited to Pfizer/Medivation.

Celgene, facing its own portfolio cliff scenario in the mid-2020s, paid a 93% premium for Juno Therapeutics in 2018.

Even GSK, which exited its oncology business in a value-creating asset swap with Novartis (see Chapter 12), could not resist the temptation to reenter the oncology space. GSK bought Tesaro in 2019 for a 110% premium to its 30-day average stock price. Investors were so disappointed with this acquisition that they knocked $10 billion off GSK’s market value, even though GSK paid only $5 billion for Tesaro.

Eli Lilly bought Loxo Oncology in 2019 for a 68% premium.

Even in non-oncology acquisitions, large pharma and large biotech tend to pay hefty multiples and extremely high premiums to their targets’ trading levels.

In the Medivation proxy, there were 15 medium-size acquisitions listed from 2011–2016, the majority of which were non-oncology related. The average target company was taken out at a 62% premium to its unaffected stock price.

Generally, the market price for a company is a reasonably good proxy for its underlying value. When paying a premium, normally 25–30% in recent years, an acquirer will typically try to justify the deal premium based on deal synergies. But with premiums in the pharmaceutical space ranging from 60% to 120%, there is simply no way the synergies can justify the purchase price.

Moreover, this takeover supply/demand imbalance is not lost on investors. Given the number of acquisitions and the magnitude of the premiums paid, it would be logical to assume that investors price at least some embedded takeover option value in the shares of these companies. Hence, a buyer must not only pay a big premium to the discounted value of its future cash flows, but likely a premium above the already embedded takeover optionality as well (see Table 21.2).

TABLE 21.2

Acquirers of Pharmaceutical Assets Paying Massive Premiums

To clarify, this is not an argument against pharmaceutical companies investing in oncology. In fact, given the fact that cancer is a leading cause of death globally, it makes sense that R&D resources are allocated there. From a financial perspective, the size of the revenue streams available to big pharma and big biotech for innovative oncology drugs justifies significant focus on cancer treatments. However, I am critical of the M&A decisions in this arena. Whether big pharma and big biotech companies buy smaller firms or allow them to remain independent, these innovative drugs will still come to market to benefit patients. The only thing that changes is the corporate ownership of these drugs.

Another reason to be somewhat critical of these oncology acquisitions is the massive cost of the treatments. How sustainable are $2 million annual price tags? While going from $922 million in revenues to $7.3 billion might look great in a spreadsheet, management teams and boards should at least be aware of the risk that extremely high price points for treatment could be curtailed in the future. That is where the returns on these acquisitions go from bad to downright ugly.

HOW SHOULD BIG PHARMA AND BIG BIOTECH RESPOND?

So, there is an incredible M&A supply/demand imbalance for big pharma and big biotech. Revenue bases are too big to grow without M&A, and a limited number of M&A targets exist to drive growth.

Here are some suggestions on what Big Pharma and Big Biotech can do:

Be willing to be smaller. If a firm is too big to grow or even maintain its current revenue base without M&A, it is OK to shrink over time. Returning excess cash to shareholders in buybacks, dividends, or special dividends prior to or during this shrinkage process can deliver substantially higher returns than value-destructive M&A and is a far more viable path than most investors or pharmaceutical executives appreciate. Reduce the firm to a size that enables it to maintain its revenue trajectory over the long term and concentrate R&D in areas of strength and differentiation.

Create a growth company/cash cow structure. If the firm is unable to sustain its top line organically, it should consider splitting into two or more companies. The growth company can have the stronger pipeline and fewer patent cliffs, and focus its R&D resources where the firm is strongest and most differentiated versus peers.

The cash cow business may have limited revenue growth or even shrink, but can pay out large dividends and potentially special dividends to a more yield-focused investor base. In 2019, Pfizer did exactly this by combining its low-to-no-growth off-patent pharmaceutical portfolio with Mylan. In 2020, Merck announced a spin-off of its women’s health, legacy brands, and biosimilars into a separate publicly traded company as well.

Asset swaps. Follow the value creation example of GSK/Novartis. Be willing to trade drugs and pipeline assets in areas where your firm is not a leader for drugs and pipeline assets where you are a recognized scientific leader and innovator. This makes a tremendous amount of sense in the pharmaceutical industry.

Take advantage of non-core divestitures. With oncology the most important focus of many large pharmaceutical companies, these firms may be willing to part with less strategic assets at reasonable prices to help fund organic and inorganic investments in oncology. Scooping up non-core divestitures is exactly what Biogen, a leader in neurology, has done in recent years:

• Paid $75 million up front and as much as $515 million in the future for a Pfizer schizophrenia drug in phase 2b clinical trials.

• Paid $300 million up front and as much as $410 million in the future for a Bristol-Myers anti-tau drug for the treatment of progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP).

• Paid $4 million up front with another $18 million option and as much as $335 million in the future to Japan-based TMS for a stroke drug.

While the ultimate fate of these drugs in the marketplace is important, my focus is on the soundness of the decisions that led Biogen to acquire them. From a purely process standpoint, these appear to be intelligent acquisitions given small up-front payments, non-core divestitures by sellers, and good fit with Biogen’s differentiated capabilities and scientific expertise in neurology.

Split company into smaller entities focused on a specific therapeutic area. This approach offers multiple advantages:

• Brings more focus to the organization

• Lessens bureaucracy

• Reduces the need for large, expensive acquisitions, given the smaller size of the new business

• Allows for smaller acquisitions and partnerships that can move the top line and potentially generate higher returns on capital

Furthermore, some of these spin-offs might become takeover targets in the future and allow the shareholder base of the spin-off to benefit from the supply/demand imbalance.

Focus on parts of business that have more steady revenue streams. Many pharmaceutical companies own non-branded pharmaceutical businesses such as vaccines, over-the-counter medications, and animal health. These businesses tend to have more stable revenue streams and reasonable growth rates, and they face materially less long-term pricing risk.

When Democratic (and increasingly Republicans as well) politicians decry the high cost of prescription drugs, they typically are not targeting over-the-counter medicines such as Tylenol, vaccines, or medicines for cats, fish, and dogs. Big pharma has been selling or spinning off these assets in recent years to take advantage of the higher valuations they command.

For example, in 2013, Pfizer IPOed and then spun off its animal health business, Zoetis, to its shareholders. Over the next five years, Zoetis’s share price almost tripled. While such spins-off make sense in the short term, the challenge is that the remaining business becomes more vulnerable to patent cliffs, and this can drive more value-destructive, high-priced M&A. From a portfolio perspective, pharmaceutical firms are divesting their “good” businesses for a premium to their own valuation multiple only to then pay exorbitant premiums for weaker pharmaceutical assets with finite life spans that generate low returns on capital.

WHAT ARE THE BROADER TAKEAWAYS FOR NON-PHARMACEUTICAL FIRMS?

Companies in other industries can learn from the challenges facing pharmaceutical firms.

• It is difficult to create long-term shareholder value when the supply/demand imbalance favors the sellers. This is where the winner’s curse comes into play. Be open to other forms of capital deployment when the returns from M&A are poor, even if that means the revenue base of the company declines for a time.

• M&A decisions should be completely independent of what is happening in the core business. Whether the top line is growing at 5% or declining at 5% should have no bearing on the return threshold for M&A. M&A should not be utilized to fill a hole in the core business. Entering into M&A for the wrong reasons rarely produces long-term shareholder wealth.

• Look at other options for value creation if you cannot maintain the current revenue base or if the business is struggling to grow as in the past. Splitting the firm into a growth company and a value company with different growth rates, different capital allocation strategies, and different shareholder bases can be an intelligent alternative to low-return M&A.