Valley Line Expansion, Public Involvement, and Sad Don

Heather Stewart and Paul R. Messinger

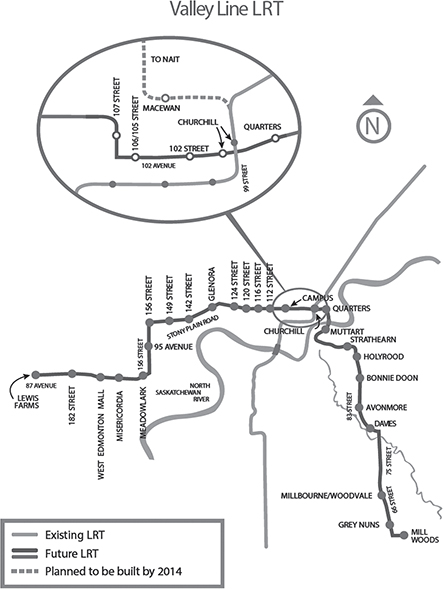

Project management of even one leg of one line of light rail transit (LRT) expansion is extremely complex, involving a large stable of outside consultants and city staff, and this expansion, part of a near doubling of the LRT coverage, was no exception (see Figure 4.1). Concomitant with the scale of the project, there was extensive engagement of the public. And there is a wealth of evidence showing the many ways that participant feedback has been incorporated into designs. But a review of reports and media also reveals processes that are occasionally inconsistent in style and detail, perhaps owing to the wide scope of activities. There was a visible learning curve in responses by public-involvement spokespersons to critical media coverage. Some early media quotes could have been interpreted as dismissive, while later in the process a more polished approach emerged. Documentation of the process was detailed, perhaps even overwhelming for department users and stakeholders. Much of the evaluation process appeared to focus on compiling comments from feedback forms, rather than providing a coherent synthesis.

Due to the size and cost of this project, public goodwill—or occasional lack of it—has had a direct impact on the financial viability of the project and the associated influence on provincial and federal funding decisions. While the overall outcomes for public goodwill and intergovernmental funding have been positive, this experience illustrates the need for a consistent and clear engagement process for long-term projects.

Figure 4.1 Planned LRT expansion

And while not part of the formal engagement process, a particularly noteworthy episode in this history was the adroit use of social and traditional media to mobilize grassroots support for funding at the provincial level.

Context and catalyst

LRT line expansion has been discussed in Edmonton for decades, going back to 1977 when the City of Edmonton approved a southeast LRT leg to Mill woods, at a projected cost of $101 million, but which was never built.31 The idea for expansion was revived in response to a growing urban population and following the development of the City’s “The Way Ahead” Strategic Vision, the “Way We Grow” municipal development plan, the “Way We Move” transportation plan, and the LRT Network Plan.3

Planning

The SE-West LRT Expansion is being conducted in five phases:5

Strategy: Conducted in and prior to 2009, the strategic plans guiding the city’s goals toward 2040 include the Municipal Development Plan, the Transportation Master Plan, and the LRT Network Plan.23,8 The public was consulted through public involvement (PI) activities including surveys.1

Concept: Corridor Definition and Concept Planning, each with their own public-involvement processes, were conducted in 2009 to 2010. A public-involvement plan (PIP) devoted to Concept Planning was developed in March 2009.4

Design 2011 to 2016: This phase includes Preliminary Engineering and Detailed Engineering, with a PIP7 detailing information sharing, idea testing for options in structural aesthetics, LRT stop/station aesthetics, landscaping, public art, transportation network connectivity, noise, and mitigating impacts, as well as active involvement in sound attenuation decision-making. This phase of public involvement was planned to include five stages:9

Design Stage 1: Pre-Consultation (Nov 2011 to Feb 2012),

Design Stage 2: Initiation (Feb to May 2012),

Design Stage 3: Consultation (May to Dec 2012),

Design Stage 4: Refinement (Sept 2012 to June 2013),

Design Stage 5: Conclusion (Jan to Oct 2013).

This phase also included costing and funding plans, which in this case involved extensive public-advocacy initiatives including #yeg4LRT in 2013 to 2014.

Build: The construction phase of the project is planned to run from 2016 to 2020 through a private contractor. 17

Operate: Active operation of the Valley Line is planned from 2020 to 2050 through a private contractor firm running low-floor LRT trains integrated with the rest of the otherwise publicly operated LRT network.13

Engagement

The public was engaged in several phases:

Corridor Selection

The SE-W corridor selection phase was facilitated by CH2M HILL consultants and representatives from multiple City of Edmonton branches. The process included three elements: Technical Studies, Public Input, and the development of the overall LRT Network Plan which included the SE-W corridor.3

In the public-involvement phase, “a total of 3,811 participants contributed to the public involvement process for both West and Southeast LRT in 2009. Over 94 public involvement activities were held, including questionnaires, workshops, online consultation, stakeholder interviews/meetings, and open houses.”3

Concept Planning

Over 700 people participated6 in the Concept Planning public-involvement Information sharing and idea-testing engagement on LRT Alignment, stations configuration, vehicle access, pedestrian/cyclist impacts, parking, and visual integration. This process shared information and tested ideas using individual and group stakeholder meetings and interviews, a series of neighborhood workshops, open houses, and a final presentation of the Recommended Concept Plan.4

Line Names

A concurrent public-involvement process gathered public feedback as one input toward naming decisions for the expanded multiline Edmonton LRT system. Over 3,000 names were submitted, shortlisted by the City, and sent to market research in 2012. The City of Edmonton Naming Committee then used the market research recommendations to approve five names in early 2013, including the name “Valley Line” for the SE to West route.

Design

The Preliminary Design process carried out five stages of public consultation, as initially planned. But only Stage 4 (Refinement) included an online report with participation numbers, showing four neighborhood-specific meetings with a total of 460 participants. This variation in reporting may be related to the broad group of leading consultants involved in the process, which have formed the “connectEd Transit Partnership” comprised of AECOM, Hatch Mott MacDonald, DIALOG, ISL, GEC, and various other specialized consultants.22

Impact

Corridor Selection

Based on data collected, city administrators screened a shortlist of potential corridors using the criteria of Feasibility, Environment and Community, and the shortlist was then evaluated against a Council-approved rubric of weighted factors to select a final preferred corridor.21

When representatives from the community opposed the preferred 87th Avenue corridor route during public consultations run by Kaleidoscope Consulting, the spokesperson for the process clarified the purposes of public involvement, reminding the public that “The current process is not meant to have stakeholders vote yes or no on the LRT line . . . but to inform them and listen to them.”2 Ultimately the 87th Avenue corridor was approved.

Concept Planning

According to the PIP, “Information from public involvement will be shared with the project team, to be considered along with technical findings and as an input into the technical evaluation process. A summary of all public input will be shared with City Council for review when considering the West and Southeast LRT Concept Plans.”4 The Concept Plan was approved by City Council in January 2011. This included detailed plans of routes in specific neighborhoods. Specific impacts from public involvement were not identified, but plan highlights included the demolition and rebuilding of the Cloverdale footbridge into a combined two-level LRT/pedestrian bridge,10 and the amendment in March 2012 which removed the previously approved Whitemud stop and replaced the Wagner stop with a revised Wagner station.6 A citizen group called Save Edmonton’s Downtown Footbridge organized to try to reverse plans to demolish the existing pedestrian bridge, calling the consultation process “vague” and “confusing”.20

Line Names

The cost to come up with LRT line names including Valley Line was estimated at $20,000 to $30,000. Then-Councilor (now Mayor) Don Iveson explained that the public engagement process was also aimed at helping to generate public advocacy which could help the City to secure more transit funding from provincial and federal governments.18

Design24

The impact of Preliminary Design consultations is reflected in the public presentation of the recommended design.

Stops: Stakeholders confirmed themes for a variety of stop/station elements, such as benches and paving.

Shelter Canopies: Of three shelter canopy options, stakeholders preferred the organic shaped canopy.

Access to Businesses and Communities: Stakeholders value ease of access to businesses and community attractions for pedestrians, cyclists, and vehicles.

Bicycles: Stakeholders indicated they want bicycle parking at or near all stops and bicycle lanes on major roadways.

Noise: Stakeholders voiced concerns about noise from the operation of the LRT.

Vibration: Stakeholders voiced concerns about vibration during construction and operations.

Shortcutting and Parking in Neighborhoods: Stakeholders voiced concerns about people parking in residential neighborhoods to access the LRT or shortcutting through neighborhoods.

Larger or Additional Park ‘N’ Ride Locations: Larger or additional Park ‘N’ Ride locations are needed

Traffic Congestion at 178th Street and 87th Avenue: Suggest elevating tracks over intersection to minimize congestion.14

Funding Negotiations and the Public—OurLRT Coalition against P3s and #yeg4LRT

The south half of the Valley line alone will cost $1.8 billion dollars. While the City of Edmonton is providing $800 million, it required additional funding partners.16

In March 2013, the Federal Government of Canada announced P3 Canada Fund investment of up to $250-million in the southbound Mill Woods half of the Valley Line. This funding requires construction and operational management of the LRT line by a private contractor.11 A coalition of Edmontonians formed to oppose this public–private partnership citing concerns about contract secrecy, erosion of public service delivery, and unionization impacts.12 The City responded with a Frequently Asked Questions sheet on P3s intended to address and alleviate concerns.13

The city concurrently also began the #yeg4LRT campaign, not as a public-involvement initiative for project planning, but as an advocacy campaign to encourage Edmontonians to express support for LRT in order to encourage funding approval by federal and provincial governments. “During the first five days of the campaign, more than 1,000 people tweeted the hashtag #yeg4LRT. A video released on February 20, 2014 was viewed more than 3,000 times on YouTube and reached more than 7,000 users on Facebook.”16

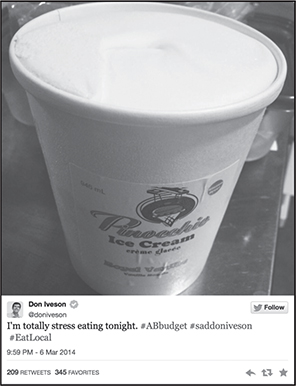

An important part of this phase of engagement began at the impetus of a private citizen seeking to help in a novel way with the use of social media. In the first week of March 2014, after the announcement of the Alberta provincial budget omitted any reference to funding for the south half of the Valley Line, a private individual, Dana DiTomaso, created a Twitter hashtag “SadDonIvenson” that acknowledged the disappointment in the Mayor’s demeanor immediately following a key speech by the Premier of Alberta (see Figure 4.2).28 Mayor Don Ivenson even entered the online conversation with a playful retweet (see Figure 4.3).30 There soon followed 1000 re-Tweets and favorites associated with the hashtag,27 and coverage of the trending social media story by the Huffington Post (a national online media website; Huffington Post 2014).29 The impact of such an action is noted by the students of the second author of this case, who discussed this event in a course paper saying, “A simple response on Twitter appears to be a simple and quick act, but it speaks volumes to the users. When citizens feel that their thoughts are acknowledged, especially by a prominent figure such as the Mayor, it can result in a newfound level of loyalty and top of mind awareness. This level of engagement can result in a deeper level of citizen investment in the form of participation and discussion,” Barry et al. (2014).26

Figure 4.2 Sad Don Hashtag (DiTomaso 2014) 28

Probably equally important, standard communications techniques were also used, including stories on traditional media and grass-roots efforts (letter writing and calls) directed to influence political officials involved, as well as meetings between the Mayor, the Alberta Finance Minister, and other cabinet ministers.

On March 11, about a week later, a commitment of $600 million in funding from the provincial government was announced ($400 million in grants and a $200-million interest-free loan to be repaid over 10 years; Kent 2014).31 A further $150 million of federal funding may be available through the Building Canada fund.19

Figure 4.3 Mayor’s Response (Iveson 2014)

Assessment and Learning

The project management of LRT expansion, even for just one half of one line, is extremely complicated and involves a huge stable of outside consultants and city staff. The task of successfully communicating public-involvement purposes and scope has been very large. The process was well-documented with dozens of key documents available online. A weakness of this documentation is that it was not archived in a user-friendly manner, as copies of public presentations are mixed with PI reports on the project pages, while other reports can only be found on the City Council SIRE archives. Inconsistent file naming practices makes it challenging for public users to find specific information or reassemble a timeline.

Based on review of reports, the process seems to be somewhat inconsistent in style and detail. While there is a wealth of evidence of consideration of and impacts from public feedback, there is also evidence that some Edmontonians felt frustrated that their ideas and concerns were not addressed. In those cases, blame was inevitably assigned to the consultation process. Some responses to these critiques in reports and media came across as dismissive (for example, listing the number of events held rather than addressing concerns about confusing consultations and reminding participants that they are not decision-makers).2,20 There may also have been lack of clarity about the decision process for isolated elements (such as the decision to remove Edmonton’s downtown footbridge). To some extent, however, claims of dismissiveness by the City or consultants or lack of clarity about the process inevitably occur from participants not satisfied with outcomes.

At the same time, there were numerous positive impacts of public engagement—with the number of positive outcomes rising as the project progressed. An important contributor to public buy-in appeared to consist of the process of solicitation from the public of names for the line (at low cost), and narrowing the over 3,000 names submitted to a shortlist of 5, for ultimate selection of the name, “Valley Line.” Citizen input was also instrumental for selection of themes for stop/station elements, benches, and paving; choice of organic shaped canopies; confirming the importance of ease of access to businesses and community attractions, provision of bicycle parking and addressing other parking concerns, and further encouragement of Park “N” Ride usage.

An evaluation of the public-involvement process, as well as parti-cipant feedback on the process, was available in general PI Reports in accordance with the PIPs for the Concept and Design phases.24,25 These reports contain much data but very little analysis on how to improve the PI process. They tend to be more of a compilation of information gathered. There is also heavy reliance on open house feedback forms as a measure of public opinion, and little integration of media and social media although both elements were planned for in the PIP. A process or rubric for weighing and analyzing these elements in order to assess the success of the PI process, note weaknesses, and suggest changes, would add practical value. The self-assessed score of “somewhat prepared” in the Design PIP Readiness Test indicates that there was room for improvement on this dimension. A consistent approach to reporting for each step across all public-involvement consultants could be helpful in tracking public involvement and developing clear expectations for the public.

The time span of this case, going back 40 years to 1977, but revived in earnest around 2009, vividly demonstrates the concepts of “hang time” and “churn” (discussed in Chapter 1 of this book). The projected budget alone for the Southeast Leg to Mill Woods has increased from $101 million in 1977 to $1.8 billion in 2014. The participants—citizens, political actors, administrators—were almost completely different from the onset. Neighborhoods and streets have been significantly updated. Public considerations, the green movement, energy costs, city extent, and transportation congestion, have all changed. But what did not happen to a large extent, as elsewhere, such as for the Walterdale Bridge, is decision lock-in and misaligned expectations. The project underwent a very effective “reset” around 2009, with detailed and thoughtful public engagement plans, that were largely carried out. And, if there was a challenge for public involvement, it may have simply been the enormous scope of the project and the volumes of data generated, calling attention to the need for synthesis and transparency for the various participants. A related opportunity arising from the extensive time span is the possibility of learning more about conducting effective public involvement over time.

Due to the size and cost of this project, public support was vital in securing funding from provincial and federal governments. This means that goodwill—or animosity—generated during the public-involvement process has a direct impact on the financial viability of expansive projects such as this. In particular, the advocacy elements of the #yeg4LRT campaign, the “#saddonivenson” thread of tweets and associated coverage, together with use of traditional media and a political “full court press” evidenced flashes of brilliance, and illustrates the importance of mobilizing public opinion for large projects such as this.

Overall, the LRT public-involvement effort merits a positive assessment, with occasional rough edges, but with evidence of increased expertise over time. This experience illustrates the need for a consistent and clearly synthesized engagement process for large projects, the relevance of hang time and participant churn, the need for securing provincial and federal funding for large projects (and the growing role of P3s), and the emerging role of social media and opportunities for new styles of communications. Construction began on the southeast leg of the Valley Line with a groundbreaking ceremony (see Figure 4.4) on April 22, 2016.15,17

Figure 4.4 Mayor Don Iveson was joined in the groundbreaking ceremony by federal Minister of Infrastructure and Communities Amarjeet Sohi, Alberta Minister of Transportation and Minister of Infrastructure Brian Mason, and representatives from Edmonton’s Indigenous communities, the Valley Line Citizen Working Groups and TransEd Partners.15

Sources

1. City of Edmonton 2008 LRT Expansion Public Survey Feedback May 2009.

2. Edmonton Journal April 12 2008 West LRT opposition heats up.

3. City of Edmonton Southeast Light Rail Transit Downtown to Mill Woods Corridor Selection Report March 2009.

4. City of Edmonton West and SE LRT Expansions Concept Public Involvement Plan March 2009.

5. City of Edmonton West and Southeast LRT Milestones Report April 2010.

6. City of Edmonton Southeast LRT Downtown to Millwoods Concept Plan Booklet April 2011.

7. City of Edmonton Southeast to West LRT: Preliminary Design Public Involvement Plan December 2011.

8. City of Edmonton Long-Term LRT Expansion LRT Network Plan March 2012, www.edmonton.ca/documents/PDF/Long_Term_LRT_Network_Plan_March_2012.pdf (accessed on October 1, 2016).

9. City of Edmonton Preliminary Design Process – Valley Line (SE to W LRT) April 2013, /www.edmonton.ca/documents/PDF/030413_Preliminary_Design_Process_SE_to_W_LRT.pdf (accessed on October 1, 2016).

10. Edmonton Sun, “Proposed Edmonton LRT bridge comes with a possible $65 million price tag,” Angelique Rodrigues, February 6, 2013. www.edmontonsun.com/2013/02/06/proposed-edmonton-lrt-bridge-comes-with-a-possible-65-million-price-tag (accessed on October 1, 2016).

11. Government of Canada and City of Edmonton Announce Public-Private Partnership (P3) to Speed up Light Rail Transit Access for Edmontonians March 2013

12. http://blogs.edmontonjournal.com/2013/09/12/coalition-fighting-p3-planned-for-southeast-edmonton-lrt/ (accessed in April 2014).

13. City of Edmonton P3 Factsheet September 2013.

14. City of Edmonton Valley Line LRT Final Preliminary Design November 2013

15. City of Edmonton Valley Line Project History, https://www.edmonton.ca/projects_plans/valley_line_lrt/concept-planning-project-history.aspx (accessed on October 1, 2016).

16. City of Edmonton YEG 4 LRT public advocacy campaign http://www.4lrt.com/ (accessed in April 2014).

17. City of Edmonton Valley Line (SE to West LRT): Mill Woods to Lewis Farms, webpage, www.edmonton.ca/projects_plans/valley-line-lrt-mill-woods-to-lewis-farms.aspx (accessed October 1, 2016).

18. Edmonton Journal, January 31 2013 City names LRT lines, grumbling follows.

19. Edmonton Journal, March 11, 2014 Edmonton’s Southeast LRT on track after province promises to fill $600 million funding gap.

20. Edmonton Journal, March 19, 2014 Edmonton LRT-expansion critics call for more transparency http://www.edmontonsun.com/2014/03/19/edmonton-lrt-expansion-critics-call-for-more-transparency (accessed in April 2014).

21. City of Edmonton LRT Route Planning & Evaluation Criteria March 2012.

22. City of Edmonton Public Engagement Process Preliminary Design Stage 4 – Refinement Report July 2013.

23. City of Edmonton Report West Light Rail Transit Downtown to Lewis Estates, October 2009; https://www.edmonton.ca/documents/PDF/2009_West_LRT_Corridor.pdf (accessed on October 1, 2016).

24. City of Edmonton. Comment Form Results – West LRT, November 2010.

25. Comment Form Results – South-East LRT, November 2010.

26. Barry, Bianca; Victor Chiu; Allison Leonard; David Manuntag; Shuai Ouyang; Danial Roth; Lowell Tautchin (2014), “Edmonton Online: Assessing the State of Municipal Online Media,” Term Paper for course BUS 480-X50, University of Alberta School of Business (Jan–April, 2014).

27. Dahlen, Jenn. (2014, April 3). Jenn Dahlen Tweet. Retrieved April 2014, from Twitter.com/jenndahl: https://twitter.com/jenndahl/status/451739472556597248

28. DiTomaso, D. (2014, March 6). Dana DiTomaso Tweet. Retrieved April 2014, from Twitter.com/danaditomaso: https://twitter.com/danaditomaso/status/441726080840253440.

29. Huffington Post. (2014, March 7). Sad Don Iveson, Edmonton Mayor, Becomes Awesome Meme. Retrieved April 2014, from Huffington Post: http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2014/03/07/sad-don-iveson-edmonton_n_4921116.html

30. Iveson, D. (2014, March 6). Don Iveson Tweet. Retrieved April 2014, from Twitter.com/doniveson: https://twitter.com/doniveson/status/441800325901471745/photo/1.

31. Kent, Gordon (1014), “It’s a go! $600-million boost from province puts southeast LRT from Mell Woods on track,” Edmonton Journal, pp. 1 & 4, March 12, 2014.