5

Formatting

When people look under the hood, we want them to be impressed with the neatness, consistency, and attention to detail that they perceive. We want them to be struck by the orderliness. We want their eyebrows to rise as they scroll through the modules. We want them to perceive that professionals have been at work. If instead they see a scrambled mass of code that looks like it was written by a bevy of drunken sailors, then they are likely to conclude that the same inattention to detail pervades every other aspect of the project.

You should take care that your code is nicely formatted. You should choose a set of simple rules that govern the format of your code, and then you should consistently apply those rules. If you are working on a team, then the team should agree to a single set of formatting rules and all members should comply. It helps to have an automated tool that can apply those formatting rules for you.

The Purpose of Formatting

First of all, let’s be clear. Code formatting is important. It is too important to ignore and it is too important to treat religiously. Code formatting is about communication, and communication is the professional developer’s first order of business.

Perhaps you thought that “getting it working” was the first order of business for a professional developer. I hope by now, however, that this book has disabused you of that idea. The functionality that you create today has a good chance of changing in the next release, but the readability of your code will have a profound effect on all the changes that will ever be made. The coding style and readability set precedents that continue to affect maintainability and extensibility long after the original code has been changed beyond recognition. Your style and discipline survives, even though your code does not.

So what are the formatting issues that help us to communicate best?

Vertical Formatting

Let’s start with vertical size. How big should a source file be? In Java, file size is closely related to class size. We’ll talk about class size when we talk about classes. For the moment let’s just consider file size.

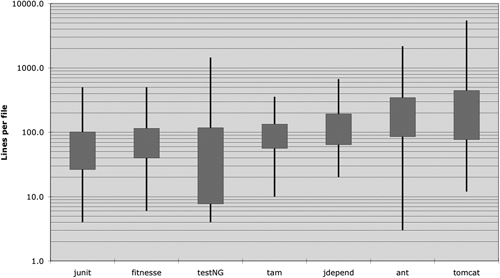

How big are most Java source files? It turns out that there is a huge range of sizes and some remarkable differences in style. Figure 5-1 shows some of those differences.

Seven different projects are depicted. Junit, FitNesse, testNG, Time and Money, JDepend, Ant, and Tomcat. The lines through the boxes show the minimum and maximum file lengths in each project. The box shows approximately one-third (one standard deviation1) of the files. The middle of the box is the mean. So the average file size in the FitNesse project is about 65 lines, and about one-third of the files are between 40 and 100+ lines. The largest file in FitNesse is about 400 lines and the smallest is 6 lines. Note that this is a log scale, so the small difference in vertical position implies a very large difference in absolute size.

1. The box shows sigma/2 above and below the mean. Yes, I know that the file length distribution is not normal, and so the standard deviation is not mathematically precise. But we’re not trying for precision here. We’re just trying to get a feel.

Figure 5-1 File length distributions LOG scale (box height = sigma)

Junit, FitNesse, and Time and Money are composed of relatively small files. None are over 500 lines and most of those files are less than 200 lines. Tomcat and Ant, on the other hand, have some files that are several thousand lines long and close to half are over 200 lines.

What does that mean to us? It appears to be possible to build significant systems (FitNesse is close to 50,000 lines) out of files that are typically 200 lines long, with an upper limit of 500. Although this should not be a hard and fast rule, it should be considered very desirable. Small files are usually easier to understand than large files are.

The Newspaper Metaphor

Think of a well-written newspaper article. You read it vertically. At the top you expect a headline that will tell you what the story is about and allows you to decide whether it is something you want to read. The first paragraph gives you a synopsis of the whole story, hiding all the details while giving you the broad-brush concepts. As you continue downward, the details increase until you have all the dates, names, quotes, claims, and other minutia.

We would like a source file to be like a newspaper article. The name should be simple but explanatory. The name, by itself, should be sufficient to tell us whether we are in the right module or not. The topmost parts of the source file should provide the high-level concepts and algorithms. Detail should increase as we move downward, until at the end we find the lowest level functions and details in the source file.

A newspaper is composed of many articles; most are very small. Some are a bit larger. Very few contain as much text as a page can hold. This makes the newspaper usable. If the newspaper were just one long story containing a disorganized agglomeration of facts, dates, and names, then we simply would not read it.

Vertical Openness Between Concepts

Nearly all code is read left to right and top to bottom. Each line represents an expression or a clause, and each group of lines represents a complete thought. Those thoughts should be separated from each other with blank lines.

Consider, for example, Listing 5-1. There are blank lines that separate the package declaration, the import(s), and each of the functions. This extremely simple rule has a profound effect on the visual layout of the code. Each blank line is a visual cue that identifies a new and separate concept. As you scan down the listing, your eye is drawn to the first line that follows a blank line.

Listing 5-1 BoldWidget.java

package fitnesse.wikitext.widgets;

import java.util.regex.*;

public class BoldWidget extends ParentWidget {

public static final String REGEXP = “’’’.+?’’’”;

private static final Pattern pattern = Pattern.compile(“’’’(.+?)’’’”,

Pattern.MULTILINE + Pattern.DOTALL

);

public BoldWidget(ParentWidget parent, String text) throws Exception {

super(parent);

Matcher match = pattern.matcher(text);

match.find();

addChildWidgets(match.group(1));

}

public String render() throws Exception {

StringBuffer html = new StringBuffer(“<b>”);

html.append(childHtml()).append(“</b>”);

return html.toString();

}

}

Taking those blank lines out, as in Listing 5-2, has a remarkably obscuring effect on the readability of the code.

package fitnesse.wikitext.widgets;

import java.util.regex.*;

public class BoldWidget extends ParentWidget {

public static final String REGEXP = “’’’.+?’’’”;

private static final Pattern pattern = Pattern.compile(“’’’(.+?)’’’”,

Pattern.MULTILINE + Pattern.DOTALL);

public BoldWidget(ParentWidget parent, String text) throws Exception {

super(parent);

Matcher match = pattern.matcher(text);

match.find();

addChildWidgets(match.group(1));}

public String render() throws Exception {

StringBuffer html = new StringBuffer(“<b>”);

html.append(childHtml()).append(“</b>”);

return html.toString();

}

}

This effect is even more pronounced when you unfocus your eyes. In the first example the different groupings of lines pop out at you, whereas the second example looks like a muddle. The difference between these two listings is a bit of vertical openness.

Vertical Density

If openness separates concepts, then vertical density implies close association. So lines of code that are tightly related should appear vertically dense. Notice how the useless comments in Listing 5-3 break the close association of the two instance variables.

Listing 5-3

public class ReporterConfig {

/**

* The class name of the reporter listener

*/

private String m_className;

/**

* The properties of the reporter listener

*/

private List<Property> m_properties = new ArrayList<Property>();

public void addProperty(Property property) {

m_properties.add(property);

}

Listing 5-4 is much easier to read. It fits in an “eye-full,” or at least it does for me. I can look at it and see that this is a class with two variables and a method, without having to move my head or eyes much. The previous listing forces me to use much more eye and head motion to achieve the same level of comprehension.

public class ReporterConfig {

private String m_className;

private List<Property> m_properties = new ArrayList<Property>();

public void addProperty(Property property) {

m_properties.add(property);

}

Vertical Distance

Have you ever chased your tail through a class, hopping from one function to the next, scrolling up and down the source file, trying to divine how the functions relate and operate, only to get lost in a rat’s nest of confusion? Have you ever hunted up the chain of inheritance for the definition of a variable or function? This is frustrating because you are trying to understand what the system does, but you are spending your time and mental energy on trying to locate and remember where the pieces are.

Concepts that are closely related should be kept vertically close to each other [G10]. Clearly this rule doesn’t work for concepts that belong in separate files. But then closely related concepts should not be separated into different files unless you have a very good reason. Indeed, this is one of the reasons that protected variables should be avoided.

For those concepts that are so closely related that they belong in the same source file, their vertical separation should be a measure of how important each is to the understandability of the other. We want to avoid forcing our readers to hop around through our source files and classes.

Variable Declarations. Variables should be declared as close to their usage as possible. Because our functions are very short, local variables should appear a the top of each function, as in this longish function from Junit4.3.1.

private static void readPreferences() {

InputStream is= null;

try {

is= new FileInputStream(getPreferencesFile());

setPreferences(new Properties(getPreferences()));

getPreferences().load(is);

} catch (IOException e) {

try {

if (is != null)

is.close();

} catch (IOException e1) {

}

}

}

Control variables for loops should usually be declared within the loop statement, as in this cute little function from the same source.

public int countTestCases() {

int count= 0;

for (Test each : tests)

count += each.countTestCases();

return count;

}

In rare cases a variable might be declared at the top of a block or just before a loop in a long-ish function. You can see such a variable in this snippet from the midst of a very long function in TestNG.

…

for (XmlTest test : m_suite.getTests()) {

TestRunner tr = m_runnerFactory.newTestRunner(this, test);

tr.addListener(m_textReporter);

m_testRunners.add(tr);

invoker = tr.getInvoker();

for (ITestNGMethod m : tr.getBeforeSuiteMethods()) {

beforeSuiteMethods.put(m.getMethod(), m);

}

for (ITestNGMethod m : tr.getAfterSuiteMethods()) {

afterSuiteMethods.put(m.getMethod(), m);

}

}

…

Instance variables, on the other hand, should be declared at the top of the class. This should not increase the vertical distance of these variables, because in a well-designed class, they are used by many, if not all, of the methods of the class.

There have been many debates over where instance variables should go. In C++ we commonly practiced the so-called scissors rule, which put all the instance variables at the bottom. The common convention in Java, however, is to put them all at the top of the class. I see no reason to follow any other convention. The important thing is for the instance variables to be declared in one well-known place. Everybody should know where to go to see the declarations.

Consider, for example, the strange case of the TestSuite class in JUnit 4.3.1. I have greatly attenuated this class to make the point. If you look about halfway down the listing, you will see two instance variables declared there. It would be hard to hide them in a better place. Someone reading this code would have to stumble across the declarations by accident (as I did).

public class TestSuite implements Test {

static public Test createTest(Class<? extends TestCase> theClass,

String name) {

…

}

public static Constructor<? extends TestCase>

getTestConstructor(Class<? extends TestCase> theClass)

throws NoSuchMethodException {

…

}

public static Test warning(final String message) {

…

}

private static String exceptionToString(Throwable t) {

…

}

private String fName;

private Vector<Test> fTests= new Vector<Test>(10);

public TestSuite() {

}

public TestSuite(final Class<? extends TestCase> theClass) {

…

}

public TestSuite(Class<? extends TestCase> theClass, String name) {

…

}

… … … … …

}

Dependent Functions. If one function calls another, they should be vertically close, and the caller should be above the callee, if at all possible. This gives the program a natural flow. If the convention is followed reliably, readers will be able to trust that function definitions will follow shortly after their use. Consider, for example, the snippet from FitNesse in Listing 5-5. Notice how the topmost function calls those below it and how they in turn call those below them. This makes it easy to find the called functions and greatly enhances the readability of the whole module.

Listing 5-5 WikiPageResponder.java

public class WikiPageResponder implements SecureResponder {

protected WikiPage page;

protected PageData pageData;

protected String pageTitle;

protected Request request;

protected PageCrawler crawler;

public Response makeResponse(FitNesseContext context, Request request)

throws Exception {

String pageName = getPageNameOrDefault(request, “FrontPage”);

loadPage(pageName, context);

if (page == null)

return notFoundResponse(context, request);

else

return makePageResponse(context);

}

private String getPageNameOrDefault(Request request, String defaultPageName)

{

String pageName = request.getResource();

if (StringUtil.isBlank(pageName))

pageName = defaultPageName;

return pageName;

}

protected void loadPage(String resource, FitNesseContext context)

throws Exception {

WikiPagePath path = PathParser.parse(resource);

crawler = context.root.getPageCrawler();

crawler.setDeadEndStrategy(new VirtualEnabledPageCrawler());

page = crawler.getPage(context.root, path);

if (page != null)

pageData = page.getData();

}

private Response notFoundResponse(FitNesseContext context, Request request)

throws Exception {

return new NotFoundResponder().makeResponse(context, request);

}

private SimpleResponse makePageResponse(FitNesseContext context)

throws Exception {

pageTitle = PathParser.render(crawler.getFullPath(page));

String html = makeHtml(context);

SimpleResponse response = new SimpleResponse();

response.setMaxAge(0);

response.setContent(html);

return response;

}

…

As an aside, this snippet provides a nice example of keeping constants at the appropriate level [G35]. The “FrontPage” constant could have been buried in the getPageNameOrDefault function, but that would have hidden a well-known and expected constant in an inappropriately low-level function. It was better to pass that constant down from the place where it makes sense to know it to the place that actually uses it.

Conceptual Affinity. Certain bits of code want to be near other bits. They have a certain conceptual affinity. The stronger that affinity, the less vertical distance there should be between them.

As we have seen, this affinity might be based on a direct dependence, such as one function calling another, or a function using a variable. But there are other possible causes of affinity. Affinity might be caused because a group of functions perform a similar operation. Consider this snippet of code from Junit 4.3.1:

public class Assert {

static public void assertTrue(String message, boolean condition) {

if (!condition)

fail(message);

}

static public void assertTrue(boolean condition) {

assertTrue(null, condition);

}

static public void assertFalse(String message, boolean condition) {

assertTrue(message, !condition);

}

static public void assertFalse(boolean condition) {

assertFalse(null, condition);

}

…

These functions have a strong conceptual affinity because they share a common naming scheme and perform variations of the same basic task. The fact that they call each other is secondary. Even if they didn’t, they would still want to be close together.

Vertical Ordering

In general we want function call dependencies to point in the downward direction. That is, a function that is called should be below a function that does the calling.2 This creates a nice flow down the source code module from high level to low level.

2. This is the exact opposite of languages like Pascal, C, and C++ that enforce functions to be defined, or at least declared, before they are used.

As in newspaper articles, we expect the most important concepts to come first, and we expect them to be expressed with the least amount of polluting detail. We expect the low-level details to come last. This allows us to skim source files, getting the gist from the first few functions, without having to immerse ourselves in the details. Listing 5-5 is organized this way. Perhaps even better examples are Listing 15-5 on page 263, and Listing 3-7 on page 50.

Horizontal Formatting

How wide should a line be? To answer that, let’s look at how wide lines are in typical programs. Again, we examine the seven different projects. Figure 5-2 shows the distribution of line lengths of all seven projects. The regularity is impressive, especially right around 45 characters. Indeed, every size from 20 to 60 represents about 1 percent of the total number of lines. That’s 40 percent! Perhaps another 30 percent are less than 10 characters wide. Remember this is a log scale, so the linear appearance of the drop-off above 80 characters is really very significant. Programmers clearly prefer short lines.

Figure 5-2 Java line width distribution

This suggests that we should strive to keep our lines short. The old Hollerith limit of 80 is a bit arbitrary, and I’m not opposed to lines edging out to 100 or even 120. But beyond that is probably just careless.

I used to follow the rule that you should never have to scroll to the right. But monitors are too wide for that nowadays, and younger programmers can shrink the font so small that they can get 200 characters across the screen. Don’t do that. I personally set my limit at 120.

Horizontal Openness and Density

We use horizontal white space to associate things that are strongly related and disassociate things that are more weakly related. Consider the following function:

private void measureLine(String line) {

lineCount++;

int lineSize = line.length();

totalChars += lineSize;

lineWidthHistogram.addLine(lineSize, lineCount);

recordWidestLine(lineSize);

}

I surrounded the assignment operators with white space to accentuate them. Assignment statements have two distinct and major elements: the left side and the right side. The spaces make that separation obvious.

On the other hand, I didn’t put spaces between the function names and the opening parenthesis. This is because the function and its arguments are closely related. Separating them makes them appear disjoined instead of conjoined. I separate arguments within the function call parenthesis to accentuate the comma and show that the arguments are separate.

Another use for white space is to accentuate the precedence of operators.

public class Quadratic {

public static double root1(double a, double b, double c) {

double determinant = determinant(a, b, c);

return (-b + Math.sqrt(determinant)) / (2*a);

}

public static double root2(int a, int b, int c) {

double determinant = determinant(a, b, c);

return (-b - Math.sqrt(determinant)) / (2*a);

}

private static double determinant(double a, double b, double c) {

return b*b - 4*a*c;

}

}

Notice how nicely the equations read. The factors have no white space between them because they are high precedence. The terms are separated by white space because addition and subtraction are lower precedence.

Unfortunately, most tools for reformatting code are blind to the precedence of operators and impose the same spacing throughout. So subtle spacings like those shown above tend to get lost after you reformat the code.

Horizontal Alignment

When I was an assembly language programmer,3 I used horizontal alignment to accentuate certain structures. When I started coding in C, C++, and eventually Java, I continued to try to line up all the variable names in a set of declarations, or all the rvalues in a set of assignment statements. My code might have looked like this:

3. Who am I kidding? I still am an assembly language programmer. You can take the boy away from the metal, but you can’t take the metal out of the boy!

public class FitNesseExpediter implements ResponseSender

{

private Socket socket;

private InputStream input;

private OutputStream output;

private Request request;

private Response response;

private FitNesseContext context;

protected long requestParsingTimeLimit;

private long requestProgress;

private long requestParsingDeadline;

private boolean hasError;

public FitNesseExpediter(Socket s,

FitNesseContext context) throws Exception

{

this.context = context;

socket = s;

input = s.getInputStream();

output = s.getOutputStream();

requestParsingTimeLimit = 10000;

}

I have found, however, that this kind of alignment is not useful. The alignment seems to emphasize the wrong things and leads my eye away from the true intent. For example, in the list of declarations above you are tempted to read down the list of variable names without looking at their types. Likewise, in the list of assignment statements you are tempted to look down the list of rvalues without ever seeing the assignment operator. To make matters worse, automatic reformatting tools usually eliminate this kind of alignment.

So, in the end, I don’t do this kind of thing anymore. Nowadays I prefer unaligned declarations and assignments, as shown below, because they point out an important deficiency. If I have long lists that need to be aligned, the problem is the length of the lists, not the lack of alignment. The length of the list of declarations in FitNesseExpediter below suggests that this class should be split up.

public class FitNesseExpediter implements ResponseSender

{

private Socket socket;

private InputStream input;

private OutputStream output;

private Request request;

private Response response;

private FitNesseContext context;

protected long requestParsingTimeLimit;

private long requestProgress;

private long requestParsingDeadline;

private boolean hasError;

public FitNesseExpediter(Socket s, FitNesseContext context) throws Exception

{

this.context = context;

socket = s;

input = s.getInputStream();

output = s.getOutputStream();

requestParsingTimeLimit = 10000;

}

Indentation

A source file is a hierarchy rather like an outline. There is information that pertains to the file as a whole, to the individual classes within the file, to the methods within the classes, to the blocks within the methods, and recursively to the blocks within the blocks. Each level of this hierarchy is a scope into which names can be declared and in which declarations and executable statements are interpreted.

To make this hierarchy of scopes visible, we indent the lines of source code in proportion to their position in the hiearchy. Statements at the level of the file, such as most class declarations, are not indented at all. Methods within a class are indented one level to the right of the class. Implementations of those methods are implemented one level to the right of the method declaration. Block implementations are implemented one level to the right of their containing block, and so on.

Programmers rely heavily on this indentation scheme. They visually line up lines on the left to see what scope they appear in. This allows them to quickly hop over scopes, such as implementations of if or while statements, that are not relevant to their current situation. They scan the left for new method declarations, new variables, and even new classes. Without indentation, programs would be virtually unreadable by humans.

Consider the following programs that are syntactically and semantically identical:

public class FitNesseServer implements SocketServer { private FitNesseContext

context; public FitNesseServer(FitNesseContext context) { this.context =

context; } public void serve(Socket s) { serve(s, 10000); } public void

serve(Socket s, long requestTimeout) { try { FitNesseExpediter sender = new

FitNesseExpediter(s, context);

sender.setRequestParsingTimeLimit(requestTimeout); sender.start(); }

catch(Exception e) { e.printStackTrace(); } } }

-----

public class FitNesseServer implements SocketServer {

private FitNesseContext context;

public FitNesseServer(FitNesseContext context) {

this.context = context;

}

public void serve(Socket s) {

serve(s, 10000);

}

public void serve(Socket s, long requestTimeout) {

try {

FitNesseExpediter sender = new FitNesseExpediter(s, context);

sender.setRequestParsingTimeLimit(requestTimeout);

sender.start();

}

catch (Exception e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

}

}

Your eye can rapidly discern the structure of the indented file. You can almost instantly spot the variables, constructors, accessors, and methods. It takes just a few seconds to realize that this is some kind of simple front end to a socket, with a time-out. The unindented version, however, is virtually impenetrable without intense study.

Breaking Indentation. It is sometimes tempting to break the indentation rule for short if statements, short while loops, or short functions. Whenever I have succumbed to this temptation, I have almost always gone back and put the indentation back in. So I avoid collapsing scopes down to one line like this:

public class CommentWidget extends TextWidget

{

public static final String REGEXP = “^#[^

]*(?:(?:

)|

|

)?”;

public CommentWidget(ParentWidget parent, String text){super(parent, text);}

public String render() throws Exception {return “”; }

}

I prefer to expand and indent the scopes instead, like this:

public class CommentWidget extends TextWidget {

public static final String REGEXP = “^#[^

]*(?:(?:

)|

|

)?”

public CommentWidget(ParentWidget parent, String text) {

super(parent, text);

}

public String render() throws Exception {

return “”;

}

}

Dummy Scopes

Sometimes the body of a while or for statement is a dummy, as shown below. I don’t like these kinds of structures and try to avoid them. When I can’t avoid them, I make sure that the dummy body is properly indented and surrounded by braces. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been fooled by a semicolon silently sitting at the end of a while loop on the same line. Unless you make that semicolon visible by indenting it on it’s own line, it’s just too hard to see.

while (dis.read(buf, 0, readBufferSize) != -1) ;

Team Rules

The title of this section is a play on words. Every programmer has his own favorite formatting rules, but if he works in a team, then the team rules.

A team of developers should agree upon a single formatting style, and then every member of that team should use that style. We want the software to have a consistent style. We don’t want it to appear to have been written by a bunch of disagreeing individuals.

When I started the FitNesse project back in 2002, I sat down with the team to work out a coding style. This took about 10 minutes. We decided where we’d put our braces, what our indent size would be, how we would name classes, variables, and methods, and so forth. Then we encoded those rules into the code formatter of our IDE and have stuck with them ever since. These were not the rules that I prefer; they were rules decided by the team. As a member of that team I followed them when writing code in the FitNesse project.

Remember, a good software system is composed of a set of documents that read nicely. They need to have a consistent and smooth style. The reader needs to be able to trust that the formatting gestures he or she has seen in one source file will mean the same thing in others. The last thing we want to do is add more complexity to the source code by writing it in a jumble of different individual styles.

Uncle Bob’s Formatting Rules

The rules I use personally are very simple and are illustrated by the code in Listing 5-6. Consider this an example of how code makes the best coding standard document.

public int getWidestLineNumber() {

return widestLineNumber;

}

public LineWidthHistogram getLineWidthHistogram() {

return lineWidthHistogram;

}

public double getMeanLineWidth() {

return (double)totalChars/lineCount;

}

public int getMedianLineWidth() {

Integer[] sortedWidths = getSortedWidths();

int cumulativeLineCount = 0;

for (int width : sortedWidths) {

cumulativeLineCount += lineCountForWidth(width);

if (cumulativeLineCount > lineCount/2)

return width;

}

throw new Error(“Cannot get here”);

}

private int lineCountForWidth(int width) {

return lineWidthHistogram.getLinesforWidth(width).size();

}

private Integer[] getSortedWidths() {

Set<Integer> widths = lineWidthHistogram.getWidths();

Integer[] sortedWidths = (widths.toArray(new Integer[0]));

Arrays.sort(sortedWidths);

return sortedWidths;

}

}