![]()

Like many computer aficionados today, Seth Schoen writes all of his software as free software to ensure that the source code—the underlying directions of computer programs—will remain accessible for other developers to use, modify, and redistribute. In so doing, Schoen not only makes technology but also participates in an effort that redefines the meaning of liberal freedom, property, and software by asserting in new ways that code is speech. A tiny portion of a 456-stanza haiku written by Schoen (2001), for example, makes just this claim:

Programmers’ art as

that of natural scientists

is to be precise,

complete in every

detail of description, not

leaving things to chance.

Reader, see how yet

technical communicants

deserve free speech rights;

see how numbers, rules,

patterns, languages you don’t

yourself speak yet,

still should in law be

protected from suppression,

called valuable speech!1

Schoen’s protest poem not only argued that source code is speech but also demonstrated it: the extensive haiku was in fact a transcoding of a short piece of free software called DeCSS, which could be used to decrypt access controls on DVDs in violation of current copyright laws. Schoen did not write this poem simply to be clever. His work was part of a worldwide wave of protests following the arrest of DeCSS’ coauthor, Johansen, and the lawsuits launched against some of those who published the software.

In this chapter, I examine how F/OSS developers like Schoen are reconfiguring what source code and speech mean ethically, legally, and culturally, and the broader political consequences of these redefinitions. I demonstrate how developers refashion liberal precepts in two distinct cultural “locations” (Gupta and Ferguson 1997): the F/OSS project, already covered in detail in the last chapter, and the context of much broader legal battles.

First, I show how F/OSS developers explore, contest, and specify the meaning of liberal freedom—especially free speech—via the development of new legal tools and discourses within the context of the F/OSS project. I highlight how developers concurrently tinker with technology and the law using similar skills, which transform and consolidate ethical precepts among developers. Using Debian as my primary ethnographic example, I suggest that these F/OSS projects have served as an informal legal education, transforming technologists into astute legal thinkers who are experts in the legal technicalities of F/OSS as well as proficient in the current workings of intellectual property law.

Second, I look at how these developers marshal and bolster this legal expertise during broader legal battles to engage in what Charles Tilly and Sidney Tarrow (2006) describe as “contentious politics.” I concentrate on a series of critical events (Sewell 2005): the separate arrests of two programmers, Johansen and Sklyarov, and the protests, unfolding between 1999 and 2003, that they provoked. These events led to an unprecedented proliferation of claims connecting source code to speech, with Schoen’s 456-stanza poem providing one of many well-known instantiations. The events are historically notable because they dramatize what normally exists more tacitly and bring visibility to two important social processes. First, they publicize the direct challenge that F/OSS represents to the dominant regime of intellectual property (and thus clarify the democratic stakes involved), and second, they make more visible and hence stabilize a rival liberal legal regime intimately connecting source code to speech.

The Ethics of Legal Contrast

Debian developers, like other F/OSS developers, are constituted as legal subjects by virtue of being extremely active producers of legal knowledge. This is an outgrowth of three circumstances. For one, developers have to learn basic legal knowledge in order to participate effectively in technological production. They must ascertain, for instance, whether the software license on the software application they maintain is compliant with licensing standards, such as the DFSG. Second, developers tend to closely track broader legal developments, especially those seen as impinging on their practices. Is the Unix company SCO suing IBM over Linux? Has the patent directive passed in the EU Parliament? Information regarding these and other relevant developments is posted widely on IRC channels, mailing lists, and especially Web sites such as Slashdot, Boing Boing, and Reddit. These channels form a crucial part of the discourse of the hacker public. Third and most important, developers largely produce their own legal artifacts, and as a result, there is a tremendous body of legal exegesis (e.g., charters, licenses, and legal texts) in the everyday life of their F/OSS projects. Projects adopt the language of the law to organize their operations, adding a legal layer to the structural sovereignty of these projects.

To be sure, there are some developers who express an overt distaste for discussions of legal policy and actively distance themselves from this domain of polluting politics. But even though the superiority of technical over legal language, even technical over legal labor, is acknowledged among hackers—some hackers will even claim that it is a waste of time (or as stated a bit more cynically yet humorously by one developer: “Writing an algorithm in legalese should be punished with death [ … ] a horrible one, by preference”)—it is critical to recognize that geeks are in fact nimble legal thinkers. One reason for this facility, I suggest, is that the skills, mental dispositions, and forms of reasoning necessary to read and analyze a formal, rule-based system like the law parallel the operations necessary to code software. Both, for example, are logic oriented, internally consistent textual practices that require great attention to detail. Small mistakes in both law and software—a missing comma in a contract or a missing semicolon in code—can jeopardize the system’s integrity and compromise the author’s intention. Both lawyers and programmers develop mental habits for making, reading, and parsing what are primarily utilitarian texts. As noted by two lawyers who work on software and law, “coders are people who write in subtle, rule-oriented, specialized, and remarkably complicated dialects”—something, they argue, that also pertains to how lawyers make and interpret the law (Cohn and Grimmelmann 2003).2

This helps us understand why it has been relatively easy for developers to integrate the law into everyday technical practice and advocacy work, and avoid some of the frustration that afflicts lay advocates trying to acquire legal fluency to make larger political claims. For example, in describing the activists who worked on behalf of the victims of the Bhopal disaster, Kim Fortun (2001, 25–54) perceptively shows how acquiring legal fluency (or failing to adequately do so) and developing the correct legal strategy is frustrating, and can lead to cynicism. Many hackers are similarly openly cynical about the law because it is seen as easily subject to political manipulation; others would prefer not to engage with the law as it takes time away from what they would rather be doing—hacking. Despite this cynicism, I never encountered any expression of frustration about the actual process of learning the law. A number of developers I worked with at the Electronic Frontier Foundation or those in the Debian project clearly enjoyed learning as well as arguing about a pragmatic subset of the law (such as a particular legal doctrinal framework), just as they did with respect to technology. Many developers apply the same skills required for hacking to the law, and as we will see, technology and the law at times seamlessly blend into each other.

To offer a taste of this informal legal scholarship—the relationship between technical expertise and legal understanding, and how legal questions are often tied to moral issues—in one free software project, I will describe some of Debian’s legal micropractices: its routine legal training, advocacy, and exegesis. In order to deepen this picture of how developers live in and through the law, I proceed to a broader struggle—one where similar legal processes are under way, but also are more visible because of the way they have circulated beyond the boundaries of projects proper.

“Living Out Legal Meaning”

Just over a thousand volunteers are participating in the Debian project at this time, writing and distributing a Linux-based OS composed over twenty-five thousand individual software applications. In its nascency, Debian was run entirely informally; it had fewer than two dozen volunteers, who communicated primarily through a single email list. To accommodate growth, however, significant changes in policy, procedures, and structure took place between 1997 and 1999. The growth of Debian, as discussed in the last chapter, necessitated the creation of more formal institutional policies and procedures. Central to these procedures is the NMP, which not only screens candidates for technical skills but also serves as a form of legal education.

Several questions in the NMP application cover what is now one of the most famous philosophical and legal distinctions in the world of free software: free beer versus free speech. Common among developers today, this distinction arose only recently, during the early to mid-1990s. A prospective Debian developer comments on the difference in an NMP application: “Free speech is the possibility of saying whatever one wants to. Software [that is] free as in beer can be downloaded and used for free, but no more. Software [that is] free as in speech can be fixed, improved, changed, [or] be used as building block for another [sic] software.”3 Some developers also note that their understanding of free speech is nested within a broader liberal meaning codified in the constitutions of most liberal democracies: “Used in this context the difference is this: ‘free speech’ represents the freedom to use/modify/distribute the software as if the source code were actual speech which is protected by law in the US by the First Amendment. [ … ] ‘[F]ree beer’ represents something that is without monetary cost.”4 This differentiation between free beer and free speech is the clearest enunciation of what, to these developers, are the core meanings of free—expression, learning, and modification. Freedom is understood foremost to be about personal control and autonomous production, and decidedly not about commodity consumption or “possessive individualism” (Macpherson 1962)—a message that is constantly restated by developers: free software is free as in speech, not in beer.

This distinction may seem simple, but the licensing implications of freedom and free speech are complicated enough that the NMP continues with a series of technically oriented questions whose answers start to enter the realm of legal interpretation. Many of these questions concern the DFSG, a set of ten provisions by which to measure whether a license can be considered free. Of these questions, one or two are fairly straightforward, such as:

“Do you know what’s wrong with Pine’s current license in regard to the DFSG?”

After looking at the license on the upstream site it is very clear why Pine is non-free. It violates the following clauses of the DFSG:

1. No Discrimination Against Fields of Endeavor—it has different requirements for non-profit vs. profit concerns.

2. License Must Not Contaminate Other Software—it insists that all other programs on a CD-ROM must be “free-of-charge, shareware, or non-proprietary.”

3. Source Code—it potentially restricts binary distribution [binary refers to compiled source code].

The sample license for an e-mail program, Pine, violates a number of DFSG provisions. With different provisions for nonprofit and for-profit endeavors, as an example, it discriminates according to what the DFSG calls “fields of endeavor.”

Developers are then asked a handful of far more technical licensing questions, among them: “At http://people.debian.org/~joerg/bad.licenses.tar.bz2 you can find a tarball of bad licenses. Please compare the graphviz and three other (your choice) licenses with the first nine points of the DFSG and show what changes would be needed to make them DFSG-free.” The answer clearly demonstrates the depth of legal expertise required to address these questions: “Remove the discriminatory clauses [ … ] allow distribution of compiled versions of the original source code [ … ] replace [sections] 4.3 with 4.3.a and 4.3.b and the option to choose.”5

After successfully finishing the NMP, some developers think only rarely about the law or the DFSG, perhaps only tracking legal developments of personal interest. Even if a developer is not actively learning the law, however, legal discourse is nearly unavoidable because of the frequency with which it appears on Debian mailing lists or chat channels. Informal legal pedagogy thus continues long after the completion of the NMP.

As an illustration, below I quote from an arcane discussion on IRC wherein a developer proposed a new Debian policy that would clarify how non-free-software packages (those noncompliant with their license guidelines) should be categorized so as to make it absolutely clear how and why they cannot be included in the main software repository, which can only have free software. I do not want to emphasize the exact legal or technical details but rather how, late on a Friday night (when the conversation happened), a developer made a policy recommendation, and his peers immediately offered advice on how to proceed, talking about the issue with such sophisticated legal vocabulary that to the uninitiated, it will likely appear as obscure, obtuse, and hard to follow. This is simply part of the “natural” social landscape of most free software projects.

<dangmang> Markel: what is your opinion about making a recommendation in policy that packages in non-free indicate why they’re in non-free, and what general class of restrictions the license has?

<markel> dangmang: well, I am not too keen on mandating people do more work for non-free packages. but it may be a good practice suggestion.

<jabberwalkie> dangmang: Then I would suggest that the ideal approach would be to enumerate all the categories you want to handle first, giving requirements to be in those categories.

<dangmang> Markel: true. could the proposal be worded so that new uploads would have to have it? [ … ]

<jabberwalkie> dangmang: You don’t want to list what issues they fail; you want to list what criteria they meet. [ … ]

<jabberwalkie> dangmang: X-Nonfree-Permits: autobuildable, modifiable, portable.

<markel> the developers-reference should mention it, and policy can recommend it, for starters.

<markel> dangmang: we need to have well defined tags.

<jabberwalkie> mt3t: “gfdl,” “firmware.” [ … ]

<jabberwalkie> mt3t: No “You may not port this to _____.”

<jabberwalkie> mt3t: You wouldn’t believe what people put in their licenses. :)

<dangmang> Markel: right. [ … ] I think I’ll start on the general outline of the proposal, and flesh things out, and hopefully people will have comments to make in policy too when I start the procedure.

More formal legal avenues are also employed. Debian developers may contact the original author (called the upstream maintainer) of a piece of software that they are considering including and maintaining in Debian. Many of these exchanges concern licensing problems that would keep the software out of Debian. In this way, non-Debian developers also undergo informal legal training. Sometimes developers act in the capacity of legal advocates, convincing these upstream maintainers to switch to a DFSG-compliant license, which is necessary if the software is to be included in Debian.

The developers who hold Debian-wide responsibilities must in general be well versed in the subtleties of F/OSS licensing. The FTP masters, who integrate new software packages into the main repository, must check every single package license for DFSG compatibility. Distributing a package illegally could leave Debian open to lawsuits.

One class of Debian developers has made legal matters their obsession. These aficionados contribute prolifically to the legal pulse of Debian in debian-legal—a mailing list that because of its legal esoterica and large number of posts, is not for the faint of heart. For those who are interested in keeping abreast but do not have time to read every message posted on debian-legal, summaries link to it in a weekly newsletter, Debian Weekly News. Below, I quote a fraction (about one-fifth) of the legal news items that were reported in Debian Weekly News during the course of 2002 (the numbers are references linking to mailing list threads or news stories):

GNU FDL a non-free License? Several [22] people are [23] discussing whether the [24] GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL) is a free license or not. If the GFDL is indeed considered a non-free license, this would [25] render almost all KDE and many other well known packages non-free since they use the GNU FDL for the documentation. Additionally, here’s an old [26] thread from debian-legal, which may shed some light on the issue.6

RFC: LaTeX Public Project License. Claire Connelly [4] reported that the LaTeX Project is in the process of considering changes to the LaTeX Project Public License. She tried to summarize some of the concerns that Debian people have expressed regarding the changes. Hence, Frank Mittelbach asked for reviews of the draft of version 1.3 of the [5] LaTeX Public Project License rather than of the current version (1.2).7

Enforcing Software Licenses. Lawrence Rosen, general counsel for the [20] Open Source Initiative, wrote an [21] article about the enforceability of software licenses. In particular, he discusses the issue of proving that somebody assented to be bound by the terms of a contract so that those terms will be enforced by a court. Authors who wish to be able to enforce license terms against users of their source code or compiled programs may find this interesting.8

Problematic BitKeeper License. Branden Robinson [3] pointed out that some of us may be exposed to tort claims from BitMover, Inc., the company that produces BitKeeper, the software that is the primary source management tool for the Linux kernel. Your license to use BitKeeper free of charge is revoked if you or your employer develop, produce, sell, or resell a source management tool. Debian distributes rcs, cvs, subversion and arch at least and this seems to be a [4] different case. Ben Collins, however, who works on both the Linux kernel and the subversion project, got his license to use BitKeeper free of charge [5] revoked.9

These are newsletter summaries, which are read by thousands of developers outside the Debian community proper as well as by Debian developers. Practical and immediate concerns are layered on global currents along with more philosophical musings. Some discussions can be short, breeding less than a dozen posts; other topics are multiyear, multilist, and may involve other organizations, such as the FSF. These conversations may eventually expand and reformulate licensing applications.

It is also worth noting how outsiders turn to Debian developers for legal advice. One routine task undertaken in debian-legal is to help developers and users choose appropriate licensing, by providing in-depth summaries of alternative licenses compliant with the DFSG. One such endeavor I witnessed was to determine whether a class of Creative Commons licenses (developed to provide creative producers, such as musicians and writers, with alternatives to copyright) was appropriate for software documentation. Debian developers assessed that the Creative Commons licenses under consideration failed to meet the DFSG’s standards, and suggested that Debian developers not look to them as licensing models. The most remarkable aspect of their analysis is that it concluded with a detailed set of recommendations for alterations to make the Creative Commons licenses more free according to the Debian licensing guidelines. In response to these recommendations, Lessig of Creative Commons contacted Evan Prodromou, one of the authors of this analysis, to try to find solutions to the incompatibilities between the DFSG and some of the Creative Commons licenses.

There is something ironic, on the one hand, about a world-renowned lawyer contacting a bunch of geeks with no formal legal training to discuss changes to the licenses that he created. On the other hand, who else would Lessig contact? These developers are precisely the ones making and therefore inhabiting this legal world. These geeks are training themselves to become legal experts, and much of this training occurs in the institution of the free software project.

Debian’s legal affairs not only produce what a group of legal theorists have identified as everyday legal awareness (Ewick and Silbey 1998; Mezey 2001; Yngvesson 1989). The F/OSS arena probably represents the largest single association of amateur intellectual property and free speech legal scholars ever to have existed. Given the right circumstances, many developers will marshal this expertise as part of broader, contentious battles over intellectual property law and the legality of software—the topic of the next section.

Contentious Politics

If hackers acquire legal expertise by participating in F/OSS projects, they also use and fortify their expertise during broader legal battles. Here I examine one of the most heated of the recent controversies over intellectual property, software, and access: the arrests of Johansen and Sklyarov. These arrests provoked a series of protests and produced a durable articulation of a free speech ethic that under the umbrella of F/OSS development, had been experiencing quiet cultivation in the previous decade. Intellectual property has been debated since its inception (Hesse 2002; Johns 2006; McGill 2002), but as media scholar Siva Vaidhyanathan (2004, 298) notes, in recent times intellectual property debates have “rarely punctured the membrane of public concern.” It was precisely during this period (1999 to 2003), and in part because of these events, that a more visible, notable, and “contentious politics” (Tilly and Tarrow 2006) over intellectual property emerged, especially in North America and Europe.

Before discussing how the emergence of this contentious politics worked to stabilize the connection between speech and code, some historical context is necessary. At the most general level, we can say a free speech idiom formed as a response to the excessive copyrighting and patenting of computer software. Prior to 1976, such an idiom had been rare. The first widely circulated paper associating free speech and source code was “Freedom of Speech in Software,” written by programmer Peter Salin (1991). He characterized computer programs as “writings” to argue that software was unfit for patents, although appropriate for copyrights and thus free speech protections (patents being for invention, and copyright being for expressive content). The idea that coding was a variant of writing was also gaining traction, in part because of the popular publications of Stanford Computer Science professor Donald Knuth (1998; see also Black 2002) on the art of programming. During the early 1990s, a new ethical sentiment emerged among Usenet enthusiasts (many of them hackers and developers) that the Internet should be a place for unencumbered free speech (Pfaffenberger 1996). This sensibility in later years would become specified and attached to technical artifacts such as source code.

Perhaps most significantly, what have come to be known as the “encryption wars” in the mid-1990s were waged over the right to freely publish and use software cryptography in the face of governmental restrictions that classified strong forms of encryption as munitions. The most notable juridical case in these struggles was Bernstein v. U.S. Department of Justice. The battles started in 1995 after a computer science student, Daniel J. Bernstein, sued the government to challenge international traffic in arms regulations, which classified certain types of strong encryption as munitions and hence subjected them to export controls. Bernstein could not legally publish or export the source code of his encryption system, Snuffle, without registering as an arms dealer. After years in court, in 1999 the judge presiding over the case concluded that government regulations of cryptographic “software and related devices and technology are in violation of the First Amendment on the grounds of prior restraint.”10

What is key to highlight is how neither Salin’s article nor the Bernstein case questioned copyright as a barrier to speech. With the rise of free software, developers began to launch a direct critique of copyright. The technical production of free software had trained developers to become legal thinkers and tinkerers well acquainted with the intricacies of intellectual property law as they became committed to an alternative liberal legal system steeped in discourses of freedom and, increasingly, free speech. If the first free speech claims among programmers were proposed by a handful of developers and deliberated in a few court cases in the early to mid-1990s, in the subsequent decade they grew social roots in the institution of the F/OSS project. Individual commitments and intellectual arguments developed into a full-fledged collective social practice anchored firmly in F/OSS technical production.

Unanticipated state and corporate interventions, though, raised the stakes and gave this rival legal morality a new public face. Indeed, it was only because of a series of protracted legal battles that the significance of hacker legal expertise and free speech claims became apparent to me. I had, like so many developers, not only taken their free speech arguments about code as self-evident but also taken for granted their legal skills in the making of these claims. Witnessing and participating in the marches, candlelight vigils, street demonstrations, and artistic protests (many of them articulated in legal terms), among a group of people who otherwise tend to shy away from such overt forms of traditional political action (Coleman 2004; Galloway 2004; Riemens 2003), led me to seriously reevaluate the deceptively simple claim: that code is speech. In other words, what existed tacitly became explicit after a set of exceptional arrests and lawsuits.

Poetic Protest

On October 6, 1999, a sixteen-year-old Johansen used a mailing list to release a short, simple software program called DeCSS. Written by Johansen and two anonymous developers, DeCSS unlocks a piece of encryption by the name of CSS (short for content scramble system), a form of Digital Rights Management (DRM) used to regulate DVDs. CSS “is a lock rather than block” (Gillespie 2007, 170) preventing a DVD with CSS from being played on a device that has not been approved by the DVD Copy Control Association (DVD CCA), the organization that licenses CSS to hardware manufactures. Before DeCSS, only computers using either Microsoft’s Windows or Apple’s OS could play DVDs; Johansen’s program allowed Linux users to unlock a DVD’s DRM to play movies on their computers. Released under a free software license, DeCSS soon was being downloaded from hundreds or possibly thousands of Web sites. In the hacker public, the circulation of DeCSS would transform Johansen from an unknown geek into a famous “freedom fighter”; elsewhere, entertainment industry executives saw his program as criminal and sought Johansen’s arrest.

Although many geeks were gleefully using this technology to bypass a form of DRM so they could watch DVDs on their Linux machines, various trade associations sought to ban the software because it made it easier to copy and potentially pirate DVDs (Gillespie 2007). In November 1999, soon after its initial spread, the DVD CCA and the MPAA sent cease-and-desist letters to more than fifty Web site owners and Internet service providers, requiring them to remove links to the DeCSS code for its alleged violation of trade secret and copyright laws, and in the United States, the DMCA. Passed in 1998 to “modernize” copyright for digital content, the DMCA’s most controversial provision outlaws the manufacture and trafficking of technology (which can mean something immaterial, such as a six-line piece of source code, or something physical) capable of circumventing copy or access protection in copyrighted works that are in a digital format. The DMCA outlaws the trafficking and circulation of such a tool, even if it can be used for lawful purposes (such as fair use copying) or is never used. “Now with the DMCA,” media scholar Tartelton Gillespie (2007, 184) perceptively notes, “circumvention is prohibited, meaning that the technologies that automatically enforce these licenses are further assured by the force of the law.”

In December 1999, alleging trade secret misappropriation, the DVD CCA filed a lawsuit against hundreds of individuals, and eventually two cases from this batch moved forward.11 In 2000, the MPAA (along with other trade associations) sued the well-known hacker organization and publication 2600 along with its founder, Eric Corley (more commonly known by his hacker handle, Emmanuel Goldstein), claiming violation of the DMCA.12 Corley would fight the lawsuits, appealing to 2600’s journalistic free speech right to publish DeCSS. As frequently happens with censored material, the DeCSS code at this time was unstoppable; it spread like wildfire.

Simultaneously, the international arm of the MPAA urged prosecution of Johansen under Norwegian law (the DMCA, a US law, had no jurisdiction there). The Norwegian Economic and Environmental Crime Unit took the MPAA’s informal legal advice and indicted Johansen on January 24, 2000, for violating an obscure Norwegian criminal code. Johansen (and since he was underage, his father) was arrested and released on the same day, and law enforcement confiscated his computers. He was scheduled to face trial three years later.

Hackers and other geek enthusiasts discussed, debated, and decried these events, and a few consistent topics emerged. The influence of the court case discussed above, Bernstein v. U.S. Department of Justice, was one such theme. This case established that software could be protected under the First Amendment, and in 1999, caused the overturning of the ban on the exportation of strong cryptography. Programmers could write and publish strong encryption on the grounds that software was speech.

F/OSS advocates, seeing the DeCSS case as a similar situation, hoped that the courts just might declare DeCSS worthy of First Amendment protection. Consider the first message posted on dvd-discuss—a mailing list that would soon attract a multitude of programmers, F/OSS developers, and activist lawyers to discuss every imaginable detail concerning the DeCSS cases:

I see the DVD cases as the natural complement to Bernstein’s case. Just as free speech protects the right to communicate results about encryption, so it protects the right to discuss the technicalities of decryption. In this case as well as Bernstein’s, the government’s policy is to promote insecurity to achieve security. This oxymoronic belief is deeply troubling, and worse endangers the very interests it seeks to protect.13

There were, it turned out, significant differences between Bernstein and DeCSS. In the Bernstein case, hackers were primarily engaged spectators. Furthermore, many free software advocates were critical of Bernstein’s decision to copyright, and so tightly control, all of his software. In the DeCSS and DVD cases, by contrast, many F/OSS hackers became participants by injecting into the controversy notions of free software, free speech, and source code (a language they were already fluent in from F/OSS technical development). Hackers saw Johansen’s indictment and the lawsuits as a violation of not simply their right to software but also their more basic right to produce F/OSS. As the following call to arms reveals, many hackers understood the attempt to restrict DeCSS as an all-out assault:

Here’s why they’re doing it: Scare tactic. [ … ] I know a lot of us aren’t political enough—but consider donating a few bucks and also mirroring the source. [ … ] This is a full-fledged war now against the Open Source movement: they’re trying to stop [ … ] everything. They can justify and rationalize all they want—but it’s really about them trying to gain/maintain their monopoly on distribution.14

Johansen was, for hackers, the target of a law that fundamentally challenged their freedom to tinker and write code—values that acquired coherence and had been articulated in the world of F/OSS production only in the last decade.

Hackers moved to organize politically. Many Web sites providing highly detailed information about the DMCA, DeCSS, and copyright history went live, and the Electronic Frontier Foundation launched a formal “Free Jon Johansen” campaign. All this was helping to stabilize the growing links between source code and software, largely because of the forceful arguments that computer code constitutes expressive speech. Especially prominent was an amicus curiae brief on the expressive nature of source code written by a group of computer scientists and hackers (including Stallman) as well as the testimony of one of its authors, Carnegie Mellon computer science professor David Touretzky, a fierce and well-known free speech loyalist. Just as they dissected free software licensing, F/OSS programmers quickly learned and scrutinized these court cases, behaving in ways that democratic theorists would no doubt consider exemplary. Linux Weekly News, for example, published the following overview and analysis of Touretzky’s testimony:

His point was that the restriction of source is equivalent to a restriction on speech, and would make it very hard for everybody who works with computers. The judge responded very well to Mr. Touretzky’s testimony, saying things like [ … ] “I think one thing probably has changed with respect to the constitutional analysis, and that is that subject to thinking about it some more, I really find what Professor Touretzky had to say today extremely persuasive and educational about computer code.” [ … ]

Thus, there are two rights being argued here. One is that [ … ] we have the right to look at things we own and figure out how they work. We even have the right to make other things that work in the same way. The other is that code is speech, that there is no way to distinguish between the two. In the U.S., of course, equating code and speech is important, because protections on speech are (still, so far) relatively strong. If code is speech, then we are in our rights to post it. If these rights are lost, Free Software is in deep trouble.15

In this exegesis, we see again how free software developers wove together free software, source code, and free speech. These connections had recently been absent in hacker public discourse. Although Stallman certainly grounded the politics of software in a vocabulary of freedom, and Bernstein’s fight introduced a far more legally sophisticated idea of the First Amendment for software, it was only with the DeCSS case that a more prolific and specific language of free speech would come to dominate among F/OSS developers, and circulate beyond F/OSS proper. In the context of F/OSS development in conjunction with the DeCSS case, the conception of software as speech became a cultural reality.

Much of the coherence emerged through reasoned political debate. Cleverness—or prankstership—played a pivotal role as well. Prodromou, a Debian developer and editor of one of the first Internet zines, Pigdog, circulated a decoy program that hijacked the name DeCSS, even though it performed an entirely different operation from Johansen’s DeCSS. Prodromou’s DeCSS stripped cascading style sheets data (i.e., formatting information) from HTML pages:

Hey, so, I’ve been really mad about the recent spate of horrible witch hunts by the MPAA against people who use, distribute, or even LINK TO sites that distribute DeCSS, a piece of software used for playing DVDs on Linux. The MPAA has got a bee in their bonnet about this DeCSS. They think it’s good for COPYING DVDs, which, in fact, it’s totally useless for. But they’re suing everybody ANYWAYS, the bastardos!

Anyways, I feel like I need to do something. I’ve been talking about the whole travesty here on Pigdog Journal and helped with the big flier campaign here in SF [ … ] , but I feel like I should do something more, like help redistribute the DeCSS software.

There are a lot of problems with this, obviously. First and foremost, Pigdog Journal is a collaborative effort, and I don’t want to bring down the legal shitstorm on the rest of the Pigdoggers just because I’m a Free Software fanatic.

DeCSS is Born

So, I decided that if I couldn’t distribute DeCSS, I would distribute DeCSS. Like, I could distribute another piece of software called DeCSS, that is perfectly legal in every way, and would be difficult for even the DVD-CCA’s lawyers to find fault with. [ … ]

Distribute DeCSS!

I encourage you to distribute DeCSS on your Web site, if you have one. [ … ] I think of this as kind of an “I am Spartacus” type thing. If lots of people distribute DeCSS on their Web sites, on Usenet newsgroups, by email, or whatever, it’ll provide a convenient layer of fog over the OTHER DeCSS. I figure if we waste just FIVE MINUTES of some DVD-CCA Web flunkey’s time looking for DeCSS, we’ve done some small service for The Cause.16

Thousands of developers posted Pigdog’s DeCSS on their Web sites as flak to further confuse law enforcement officials and entertainment industry executives, since they felt these people were clueless about the nature of software technology. Dozens of these developers (including Johansen) received cease-and-desist letters demanding they take down a version of DeCSS that was completely unrelated to the decryption DeCSS.

Clever re-creations of the original DeCSS source code (originally written in the C programming language) using other languages (such as Perl) also began to proliferate, as did translations into poetry, music, and film. A Web site hosted by Touretzky, called the Gallery of CSS DeScramblers, showcased a set of twenty-four of these artifacts—the point being to demonstrate the difficulty of drawing a sharp line between functionality and expression in software.17 Touretzky, an expert witness in the DeCSS case, said as much in the introductory statement to his gallery:

If code that can be directly compiled and executed may be suppressed under the DMCA, as Judge Kaplan asserts in his preliminary ruling, but a textual description of the same algorithm may not be suppressed, then where exactly should the line be drawn? This web site was created to explore this issue.18

Here is a short snippet (about one-fifth) of the original DeCSS source code written in the C programming language:

void CSSdescramble(unsigned char *sec,unsigned char *key)

{

unsigned int t1,t2,t3,t4,t5,t6;

unsigned char *end=sec+0x800;

t1=key[0]^sec[0x54]|0x100;

t2=key[1]^sec[0x55];

t3=(*((unsigned int *)(key+2)))^(*((unsignedint *)(sec+0x56)));

t4=t3&7;

t3=t3*2+8-t4;

sec+=0x80;

t5=0;

while(sec!=end)

{

t4=CSStab2[t2]^CSStab3[t1];

t2=t1>>1;

t1=((t1&1)<<8)^t4;

t4=CSStab5[t4];

t6=(((((((t3>>3)^t3)>>1)^t3)>>8)^t3)>>5)&0xff;

t3=(t3<<8)|t6;

t6=CSStab4[t6];

t5+=t6+t4;

*sec++=CSStab1[*sec]^(t5&0xff);

t5>>=8;

}

Compare this fragment to another one written in Perl, a computer language that hackers regard as particularly well suited for crafting poetic code because longer expressions can be condensed into much terser, sometimes quite elegant (although sometimes quite obfuscated) statements. And indeed the original DeCSS program, composed of 9,830 characters, required only 530 characters in Perl:

#!/usr/bin/perl -w

# 531-byte qrpff-fast, Keith Winstein and Marc Horowitz

# MPEG 2 PS VOB file on stdin -> descrambled output on stdout

# arguments: title key bytes in least to most-significant order

$_=‘while(read+STDIN,$_,2048){$a=29;$b=73;$c=142;$t=255;@t=map{$_%16or$t^=$c^=($m=(11,10,116,100,11,122,20,100)[$_/16%8])&110;$t^=(72,@z=(64,72,$a^=12*($_%162?0:$m&17)),$b^=$_%64?12:0,@z)[$_%8]}(16..271);if((@a=unx”C*”,$_)[20]&48){$h=5;$_=unxb24,join”“,@b=map{xB8,unxb8,chr($_^$a[—$h+84])}@ARGV;s/ [ … ] $/1$&/;$d=unxV,xb25,$_;$e=256|(ord$b[4])<<9|ord$b[3];$d=$d>>8^($f=$t&($d>>12^$d>>4^$d^$d/8))<<17,$e=$e>>8^($t&($g=($q=$e>>14&7^$e)^$q*8^$q<<6))<<9,$_=$t[$_]^(($h>>=8)+=$f+(~$g&$t))for@a[128..$#a]}print+x”C*”,@a}’;s/x/pack+/g;eval

If Perl allows programmers to write code more poetically (in this case, being terse) than other computer languages, Schoen took up the challenge of publishing a bona fide poem in the form of an epic haiku—456 individual stanzas written over the course of just a few days. Schoen, who was inspired by the clever re-creations of DeCSS compiled in the gallery, wrote the poem to deliver a stark and clear political message. The author asserts that source code is not a metaphor or similar to expression but rather is expression, and he makes this point by re-creating the original DeCSS program as a poem. This bit of poetry is now well known among hackers as an exemplary hack for displaying the cleverness that hackers collectively value. Schoen opens his poem by thanking Touretzky and then moves immediately to abandon his “exclusive rights” clause of the copyright statute, indexing the direct influence of F/OSS licensing.

How to Decrypt a DVD: In Haiku Form

(Thanks, Prof. D. S. T.)

(I abandon my

exclusive rights to make or

perform copies of

this work, U. S. Code

Title Seventeen, section

One Hundred and Six.)

Muse! When we learned to

count, little did we know all

the things we could do

some day by shuffling

those numbers: Pythagoras

said “All is number”

long before he saw

computers and their effects,

or what they could do

by computation,

naive and mechanical

fast arithmetic.

It changed the world, it

changed our consciousness and lives

to have such fast math

us and anyone who cared

to learn programming.

Now help me, Muse, for

I wish to tell a piece of

controversial math,

for which the lawyers

of DVD CCA

don’t forbear to sue:

that they alone should

know or have the right to teach

these skills and these rules.

(Do they understand

the content, or is it just

the effects they see?)

And all mathematics

is full of stories (just read

Eric Temple Bell);

and CSS is

no exception to this rule.

Sing, Muse, decryption

once secret, as all

knowledge, once unknown: how to

decrypt DVDs.

Here, the author first frames the value of programming in terms of mathematics along with its antagonists in the entertainment industry, intellectual property statutes, lawyers, and judges—all of which use software without recognizing, much less truly understanding, the embedded creative labor and expressive value. This critique is made explicit through a question: “Do they understand the content, or is it just the effects they see?” The author then launches into a long mathematical description of the forbidden CSS code represented in DeCSS. The expert explains the “player key” of CSS, which is the proprietary piece that enacts the access control measures:

So this number is

once again, the player key:

(trade secret haiku?)

Eighty-one; and then

one hundred three—two times; then

two hundred (less three)

four; and last (of course not least)

the humble zero

The writer states the access control mathematically, but using words. From these lines alone a proficient enough programmer can deduce the encryption key. Thus the poem makes a similar point to the one made in the amicus brief—namely, that “at root, computer code is nothing more than text, which, like any other text, is a form of speech. The Court may not know the meaning of the Visual BASIC or Perl texts [ … ] but the Court can recognize that the code is text.”19

The author then conveys that many F/OSS programmers conceive of their craft as technically precise (and so functional) yet fundamentally expressive, and as a result, worthy of free speech protection. In formally comparing code to poetry in the medium of a poem, Schoen displays a playful form of clever and recursive rhetoric valued among hackers; he also articulates both the meaning of the First Amendment and software to a general public:

We write precisely

since such is our habit in

talking to machines;

we say exactly

how to do a thing or how

every detail works.

The poet has choice

of words and order, symbols,

imagery, and use

of metaphor. She

can allude, suggest, permit

ambiguities.

She need not say just

what she means, for readers can

always interpret.

Poets too, despite

their famous “license” sometimes

are constrained by rules:

How often have we

heard that some strange twist of plot

or phrase was simply

“Metri causa,” for

the meter’s sake, solely done

“to fit the meter”?

Although this haiku contains novel assertions (the tight coupling between source code and speech), it is also through its inscription into a tangible and especially culturally captivating medium (a hack with playful, recursive qualities) that the assertion is transformed into a firm social fact. Or to put it another way, here a recondite legal argument makes its way into wide and public circulation as well as consumption. This is how discourse meant for public circulation, as Warner (2002, 91) has noted, “helps to make a world insofar as the object of address is brought into being partly by postulating and characterizing it.”

Free Dmitry!

The protests, poetry, and debate demonstrate how programmers and hackers quickly became active participants in the drama of law and free software in the digital age. This narrative process by which the law takes on a meaning to individuals through a period of contentious politics would accelerate thanks to the simultaneous (although completely unrelated) DMCA infraction and arrest of another programmer, Sklyarov. Because Sklyarov faced up to twenty-five years in jail, programmers in fact only grew more infuriated with the state’s willingness to police technological innovation and software distribution through the DMCA. After Sklyarov’s arrest, protest against the DMCA and the hacker commitment to a discourse of free speech only increased in emotional intensity, and worked to extend and fortify the narrative process already under way.

This case would also prove far more dramatic than Johansen’s because of the timing and place of the arrest. As mentioned earlier, Sklyarov was arrested while leaving Defcon, one of the largest hacker conferences in the world. During the conference, he had presented a paper on security breaches and weaknesses within the Adobe e-book format. He purportedly violated the DMCA by writing a piece of software for his Russian employer, Elcomsoft, that unlocks Adobe’s e-book access controls and subsequently converts the files into PDF format. For the FBI to arrest a programmer at the end of this conference was a potent statement. It showed that federal authorities would act on corporate demands to prosecute hackers under the DMCA.

FBI agents attend Defcon, but there is a well-known, although tacit, agreement that these agents, immediately identifiable by their L. L. Bean khaki attire (normal Defcon regalia leans toward black clothing, T-shirts, and body piercings), not interfere with the hackers. Despite their presence since the con began in 1993, FBI agents had never arrested a hacker at Defcon. (Typically, any arrests were local, and due to excessively rowdy and drunken behavior.) The first-ever FBI arrest of a hacker signaled a one-sided renegotiation of the relationship between legal authority and the hacker world.

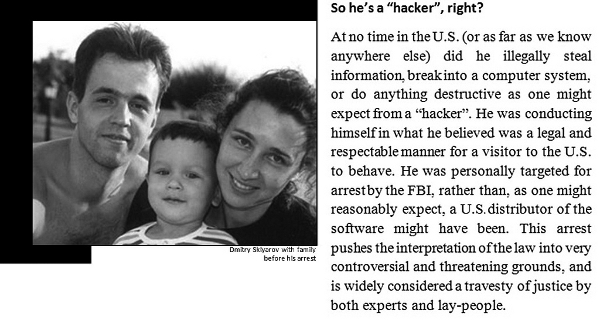

On July 17, 2001, as Sklyarov was leaving the conference, federal agents whisked him away to an undisclosed jail in Nevada. Weeks later, he was released in the middle of a fervent Free Dmitry campaign. Sklyarov’s arrest and related court hearings also prompted conversations built on those initiated by Johansen’s arrest and the resultant DeCSS lawsuits. But the Free Dmitry campaign was organized more swiftly, was more visible, and directly attacked Adobe, the company that had urged the US Department of Justice to make the arrest. Its success, argues media scholar Hector Postigo (2010), followed in part from how quickly activists organized the campaign, which framed the issues in strong but accessible language, and actively sought to distance the association between Dmitry and “hacker,” as an excerpt from one of the organizing pamphlets makes clear, reinforced by the featured family photo included in the flyer (see figure 5.1).

FIGURE 5.1. So he’s a “hacker,” right?

Original pamphlet produced by Barrington King, http://www.wyrdwright.com/sklyarov/ (accessed on September 10, 2010). Excerpt and photo taken from Free Version A, produced with ps2pdf (pdf v 1.3 compatible) by Mike Castleman.

Developers organized protests across US cities (such as Boston, New York, Chicago, and San Francisco) and in Europe as well as Russia. San Francisco, where I was doing my fieldwork at the time, was a hub of political mobilization. Even though Sklyarov was in no fashion part of or identified with the world of F/OSS development, local F/OSS developers were behind a slew of protest activities, including a protest at Adobe’s San Jose headquarters, a candlelight vigil at the San Jose public library, and a march held after Linux World on August 29, 2001, that ended up at the federal prosecutor’s office.

At a fund-raiser that followed the march to the prosecutor’s office, Stallman, the founder of the FSF, and Lessig, the superstar activist-lawyer, gave impassioned speeches. Sklyarov, in a brief appearance, thanked the audience for their support. The mood was electric in an otherwise-cool San Francisco warehouse loft. Lessig, who had recently published his Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace, a book that was changing the way F/OSS developers understood the politics of technology, fired up the already-animated crowd with charged declarations during his speech:

Now this is America, right? It makes me sick to think this is where we are. It makes me sick. Let them fight their battles in Congress. These million-dollar lobbyists, let them persuade Congressmen about the sanctity of intellectual property and all that bullshit. Let them have their battles, but why lock this guy up for twenty-five years?20

Most programmers agreed with Lessig’s assessment: the state had gone too far in its uncritical support of the copyright industries. The protests had an immediate effect. Adobe withdrew its support of the case, and eventually, the court dropped all charges against Sklyarov on the condition that he testify in the subsequent case against his employers, which he did. In December 2002, the jury in that case acquitted Elcomsoft, Sklyarov’s employer. Johansen was acquitted just over a year later because the charges against him were seen as too shaky for prosecution (the law he was arrested under had nothing to do with DRM). Johansen still writes free software (including programs that subvert DRM technologies) as well as a blog, So Sue Me, and is admired among F/OSS hackers.

The DeCSS lawsuits were decided between 2001 and 2004, and even though the courts were persuaded that the DeCSS was a form of speech, they continued to uphold copyright law and deemed DeCSS unfit for First Amendment protection. In one of the 2600 cases, Universal City Studios Inc. v. Reimerdes, Judge Lewis A. Kaplan went so far as to declare that the court’s decision meant to “contribute to a climate of appropriate respect for intellectual property rights in an age in which the excitement of ready access to untold quantities of information has blurred in some minds the fact that taking what is not yours and not freely offered to you is stealing.”21

Many developers and hackers were deeply disappointed with these decisions, which equated DeCSS with theft, and were shocked about how narrow the consequences of Bernstein turned out to be. Many developers, however, emboldened and galvanized by the collective outpouring they organized or witnessed, continued to assert, in passionate and often considerable legal detail, a different narrative to that of piracy and stealing. Schoen, the DeCSS haiku author who questioned the cultural assumptions and stereotypes at play with Judge Kaplan’s doctrinal reasoning, published one of the most incisive accounts:

It’s hard to avoid the inherent sympathy Judge [Marilyn Hall] Patel bears toward Professor Bernstein (a speaker whose expression is crushed by the awesome might of government bureaucracy) or the equally apparent suspicion with which Judge Kaplan regards Emmanuel Goldstein (a self-avowed hacker seemingly hell-bent on trouble). These attitudes seem to me to be visible behind all the doctrinal questions; without committing myself for all time to a position in a contentious area of legal theory, I would say that Judge Patel fought to show why her case was a free speech case and that Judge Kaplan fought to show why his was not. The question of which approach seems natural would then be not primarily a question of legal doctrines, standards, or precedents. It would instead be a conceptual, cultural battle: shall programs be compared to epidemics of disease (evil, menacing, worthy only of quarantine) or to books in libraries (the cornerstones of our culture and our civilization)?22

Even if the court cases never declared source code as First Amendment speech, the arrests, lawsuits, and protests cemented this connection. Hackers, programmers, and computer scientists would continue to be motivated to transform what is now their cultural reality—a rival liberal morality—into a broader legal one by arguing that source code should be protectable speech under the US Constitution and the constitutions of other nations.

Conclusion

The law, in its formal and informal dimensions, clearly saturated this story, acting as a double-edged sword that constrains and enables (and produces) new possibilities. In an article on liberal law, Jane Collier, Bill Maurer, and Liliana Suarez-Navaz note how liberal law, riddled with productive contradictions, works to sanction an individuated identity. If “bourgeois law is constructed as a system of rules that people are required to obey, whatever their personal desires,” at the same time it also encourages “expressions of individual contention or will, particularly in private contract that legal agencies enforce” (Collier, Maurer, and Suarez-Navaz 1997, 4). While liberal law certainly individuates its citizens (and private contract has been one privileged route by which this is accomplished), free software is just one example of what we might think of as a type of legal populism, especially prevalent in the United States since the civil rights era, under which collectives take the law into their own hands, and whereby the content of the law matters as much as its formal attributes to recharge and change cultural meaning. If the law, to use the formulation offered by Geertz (1983, 184), is “part of a distinctive manner of imagining the real,” what I have shown in this chapter is how the law becomes social reality, and in effect, constitutes particular cultural meanings related to personhood, expression, creativity, and thought.

This period of political protest and avowal, like much of hacker activity, is rooted initially in a defense of the existing hacker lifeworld, insofar as intellectual property law in basic ways challenges the capacity of hackers to do their work. Yet this defense does not merely leave the hacker lifeworld untouched; it in fact transforms it in significant ways, most especially by bringing hackers into more quotidian, though quite persistent, contact with the language of law. Software developers have now deployed and also contested the law to reconfigure central tenets of the liberal tradition—and specifically the meaning of free speech—to defend their productive autonomy.

Many hackers, understood to be technologists, became legal thinkers and tinkerers, undergoing legal training in the context of the F/OSS project while building a corpus of liberal legal theory that links software to speech and freedom. By means of lively protests and prolific discussions, almost continuously between 1999 and 2003, hackers as well as new publics debated the connection between source code and speech. This link became a staple of free software moral philosophy, and has helped add clarity in the competition between two different legal regimes (speech versus intellectual property) for the protection of knowledge and digital artifacts. Now other actors, such as activist lawyers, are consolidating new projects and bodies of legal work that challenge the shape along with the direction of intellectual property law.

To be sure, the idea of free speech has never held a single meaning across the societies that have valued, instantiated, or debated it. Yet it has come to be seen as indispensable for a healthy democracy, a free press, individual self-development, and academic integrity. It is, as one media theorist aptly puts it, “as much cultural commonplace as an explicit doctrine” (Peters 2005, 18). F/OSS is an ideal vehicle for examining how and when technological objects, such as source code, are invested with new liberal meanings, and with what consequences. By showing how developers incorporate legal ideals like free speech into the practices of everyday technical production, I trace the path by which older liberal ideals persist, albeit transformed, into the present.

This is key to emphasize, for even if we can postulate a relation between a product of creative work—source code—and a democratic ideal—free speech, there is no necessary or fundamental connection between them (Ratto 2005). Many academics and programmers have argued convincingly that the act of programming should be thought of as literary—“a culture of innovative and revisionary close reading” (Black 2002, 23; see also Chopra and Dexter 2007). As with print culture of the last two hundred years (Johns 1998), this literary culture of programming has often been dictated and delineated by a copyright regime whose logic is one of restriction. New free speech sensibilities, which fundamentally challenge the coupling between copyright and literary creation, must therefore be seen as a political act and choice, requiring sustained labor and creativity to stabilize these connections.

Hackers have been in part successful in this political fight because of their facility with the law; because of years of intensive technical training, they have not only easily adopted the law but also tinkered with it to suit their needs. This active and transformative engagement with the law raises a set of pressing questions about the current state of global politics and legal advocacy. As Jean Comaroff and John Comaroff (2003, 457) note, the modern nation-state is one “rooted in a culture of legality”—a culture that in recent years has become ever more pervasive, especially in the transnational arena. Whether it is the constitutional recognition of multiculturalism across Latin America and parts of Africa, or new avenues of commoditization like the patenting of seeds, these new political and economic relationships are “heavily inscribed in the language of the law” (ibid.). Given the extent to which esoteric legal codes dominate so many fields of endeavor, from pharmaceutical production to financial regulation to environmental advocacy, we must ask to what extent informal legal expertise, of the sort exhibited by F/OSS developers, is a necessary or useful skill for social actors seeking to contest such regimes, and where and how advocates acquire legal literacy. Legal pedagogy keeps the issues of freedom present, sometimes through the minuscule redefinitions that occur through discussion, legal exegesis, and the production of legal artifacts such as legal tests and guidelines. We must remain alert to these amateur forms of legalism and the alternative social forms that they imply.