2. UNDERSTANDING IT-DRIVEN SERVICE REQUIREMENTS

Don’t ever take a fence down until you know the reason it was put up.

G K Chesterton

2.1 What is a business service?

Think about any airline. BA, United, America, Easy Jet, it doesn’t matter. Now, define the service. Depending on your perspective, this service could be taking people from point A to B. Another person might add the word ‘safely’. Someone else might highlight that buying a ticket is part of that service. What about on-board catering? And we have not even started to discuss the services that begin at the airport, including the check in, baggage membership of frequent flyer clubs, etc. And, remember, the enterprise (that is, the owner of the airline) may only be in business to make money, and not necessarily to provide the best service to the passenger. Now, which of the services we mentioned is a business service and which is IT? The answer is that all are business services that depend on IT and the ‘IT services’ and organisational units we mentioned in chapter one support the lines of business of the air carrier.

A service can be defined from two perspectives: the demand side and the supply side, although both definitions should match with regards to the different outcomes they produce. Suppliers (providers) will often focus on the development and the maintenance of the output that is asked for. Business (or demand) focuses on attaining the outcome. And all parties anticipate that the output should be predicated on those outcomes. Of course, this is not an easy thing to do but mostly through inattention, providers sometimes forget (or perhaps do not know how) to define services from the perspective of customer needs and responsibility. All enterprises depend on IT services in their business processes. A random list of enterprise business services demonstrates this:

• Government subsidy for different business sectors (e.g. agriculture, regional economy) – this will involve a large body, maybe more than one, to organise and execute the processes and multiple IT applications to make it all work.

• Pensions and social security payment – imagine all the activities, processes and underlying IT systems needed to pay pensions and social security to those who are entitled.

• Online education (actually, online just about anything) – including portals, registers and all the different business processes, such as registration, distribution, examinations, etc.

• Insurance agreements – including screening and accepting applicants or paying claims to those who are entitled.

Services are enterprise-wide. As a result, we should focus on designing services that fulfil the requirements of any customer in any sector. A final ‘definitive’ definition of ‘services’ is therefore hard to find. Thus, we prefer an approach in which we define services as having key characteristics, rather than definitive statements that are open to interpretation:

• Services may not be entirely tangible. For example, an ‘office cleaning service’.

• Services comprise of a series of activities. For example, the request and delivery of items that must go through procurement.

• Services are often produced and consumed directly, such as the handling of a request for information or making reservations.

• The customer may (to a greater or lesser extent) participate in the provision of services, such as creating access cards that require a photograph or obtaining photographs for a passport. Another example is that of an office move to a new geographic location.

• The customer participates actively in the service, where services are in fact performed (and manufacturing only takes place) when the customer makes a request. On demand publishing, for example.

• Services are most often not ‘pure IT’ but more often are heavily IT driven.

Enterprise IT services are supported by the IT infrastructure, which is comprised of hardware, software, and computer-related communications. The technology within IT intensive services may:

• Range from access to a single application (such as a payroll system) to a complex set of facilities including many applications (providing state pensions or social services).

• Be provided from a central system or, as is the case with office automation, could be spread across many hardware and software platforms.

Defining an IT service that is deployed in support of business services can be controversial.

According to ITIL, the most widely respected framework for managing the IT infrastructure:

‘A service is the provision, operation and maintenance of an (IT) infrastructure, enabling access to information systems, applications and data to the business transaction of a customer, in support of one or more business areas. It may be perceived by the customer of the service as a coherent and self-contained entity.’

The ITIL definition is predicated on the reality that operational running pertains to all business services and ITIL of course focuses on the ‘effective running and maintenance of the IT infrastructure’.2

In this guide to the fundamentals of collaborative business service design, we focus on a wider definition, which recognises that IT-driven services are defined from a business perspective.

2.2 Service lifecycle

Life would be simple if designing services happened only in a ‘greenfield’. The reality is much harsher. Architectural service design is almost always in a ‘brownfield’ situation, for example. Many decisions have been made in advance, the market is a given, and you must deal with legacy systems and methods that would be costly, if not impossible, to ignore. Policies are set, people have made their mind up about things that you want to change, but cannot, and IT is as usual, changing everything in sight trying to keep up with the latest digitisation strategies and trends.

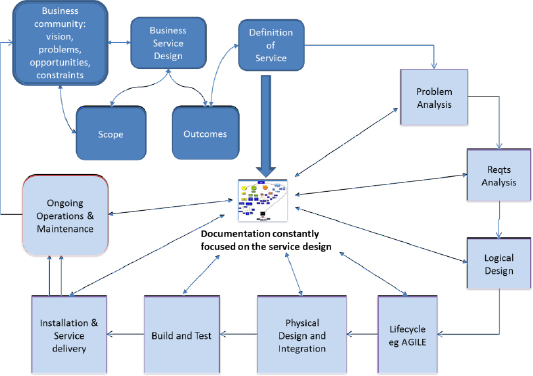

We must accept that services have a lifecycle. They exist and eventually they change. Sometimes, they are retired from use altogether. A service lifecycle (Figure 2.1) is a representation of the complete lifetime of a service from initial conception to final decommissioning. Generically, you will find that any lifecycle model does not differ very much from that shown. The major difference in most is what kind of service (business, IT-driven business, IT development or IT infrastructure) is the subject. This figure is the focus for all the hundreds of IT good practices shown in Figure 1.2.

A project lifecycle, which is really all that a service lifecycle claims to be, can be used for planning purposes. It is the sequence of stages through which services pass. The lifecycle covers the following stages:

• The starting point – when the service need is first specified and written.

Figure 2.1: Service lifecycle

• The service development lifecycle – the period of time that begins with the decision to develop a service and ends when an acceptable service is delivered for implementation.

• The service implementation.

• The service as part of the operation.

• The decision to renew, improve or decommission the service. In the case of renewal or improvement, the lifecycle starts again with development. In the case of decommissioning, activities must be put in place to phase out the service.

Agile development really means just following these same steps very quickly. A total service design must incorporate all aspects of a service. Thus, a business service using IT will almost certainly involve applications development; an engineered device, a radar installation or car, for example, will involve engineers as well as applications developers. So, a service incorporates lots of building blocks. Each building block has its own lifecycle. For example an application, something ‘used’ by someone to transact an automated component of an IT intensive business service, is part of the total service that incorporates the ITIL service lifecycle, which focuses on IT supporting services.

2.3 Requirements origin and perspective

An important success factor to obtain the services that you need (but did not necessarily ask for) is getting the requirements right. This is not as easy as one might think. Somehow, there is a gap between the wants and needs of the business and the offerings suppliers provide.

So, why is it so difficult to get the requirements right? What are the pertinent questions a business should ask their provider of their IT services to get things right? How does the business get a grip on IT development in relation to the IT-driven business processes?

When it comes to designing IT intensive business services and models, approaches are few and far between. To obtain better insight, to correct for prejudices and miscommunications of the necessary requirements, and to get a better grip on IT development, we need to understand all the differing requirements of the different stakeholders and balance these in an optimal design that is fit for use. We used existing best practices to build the approach that we have called business service design. This approach favours:

• A structured working method that improves categorisations and retrieval of essential issues and requirements, and decreases complexity (leading to improved clarity).

• Simultaneously combining analysis and converging perspectives.

• Eliminating error by documenting results.

• Involving all essential stakeholders and their perspectives/concerns.

How do we obtain the correct requirements for your IT-intensive service offering and where do they come from? Well, they arise from all the different stakeholders that have a stake in the service offering. We explicitly state all the stakeholders because we think requirements should come from demand and supply

Of course, it is not the intention for all stakeholders to necessarily agree. Sometimes, requirements cannot be matched because of non-existent technology, or because the costs are too high. What is important is that all stakeholders agree on the service offering that will be designed. And not only from the demand side, the supplier side must also agree because the design must be attainable within the parameters set by the customer.

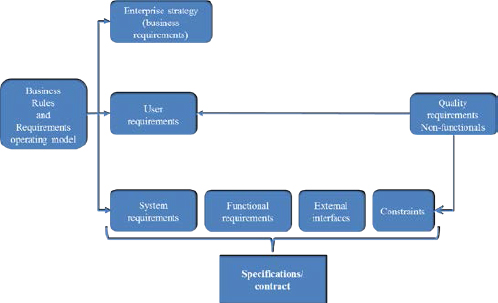

We distinguish between different sets or groups of requirements in Figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2: The requirement roadmap

Strategic business requirements comprise business requirements and business rules. Business requirements define objectives and strategies that define the mission and vision of the enterprise. For example, accountability and responsibilities, specific policies about privacy or other restrictions brought about by corporate governance policies.

Within operational requirements one can distinguish functional requirements, system requirements, external interfaces and technical constraints.

• Functional requirements – specify the behaviour of the service and the functions of the services. For example, how it records, computes, transforms or transmits data.

• System requirements – describe the requirements for a service that is composed of multiple parts (systems or other services, such as IT services).

• External interfaces – define and describe the interactions with various other resources, such as services or systems that are (or must be) in place.

• Technical constraints – describe constraints that originate through technology choices (or constraints), policy demands, legislation etc.

There is then a dramatic difference between business rules design and operational/functional design. Operational personnel will need to know (IT) functionality. The business will also want to be assured that accurate processing will take place. However, their primary focus is on the outcome of the information being processed.

The business though cannot abrogate responsibility for technology decisions to the supplier. For example, if a file sharing utility is needed and the decision is entirely at the discretion of the supplier then something (such as Dropbox or a similar offering) might be the proposed technology solution. But the supplier might be completely unaware that corporate policy forbids the use of commercial external platforms.

2.4 Business service design

Business Service Design (BSD) is built on practical principles and best practices. The basic assumptions of BSD are that:

• The target formulated by the customer (‘the business outcome’) becomes ‘a beacon’ for all parties involved in the design throughout the design process.

• There is an owner of the service design offering who feels responsible for the entire quality and effectiveness of the service lifecycle.

• Exploration and design with input from every relevant discipline is possible, including the customer, financial controller, users, CIO or deputy CIO, CIO adviser, strategist, IT management consultant, business consultant, information analyst, IT architect, owner of the service, service manager, programme manager, sourcing manager, purchasing, contract manager, service level manager, account manager. If necessary, even the company cat!

• A service, a system or an application is not simply the design result. The result is a total set of requirements of the desired service (including the business requirements, user requirements, demand-side and customer requirements, and functional and system requirements).

BSD merges the pragmatism and logic of the UK Government Gateway method, which is the method of service blueprinting and that of the stakeholder approach to gaining consensus. This includes the:

• Gateway method – The Gateway process defines review gates, or points throughout the lifecycle of acquisition and/or implementation of products and/or services. Gateways are undertaken for all levels of procurement projects, as defined by the project profile model. Requests for Gateway reviews are initiated by senior responsible owners/project owners.3

• Service blueprinting: This is a customer focused approach for service innovation and service improvement. A service blueprint allows an enterprise to explore all the issues inherent in creating or managing a service. The service processes are visualised, points of contact and accompanying actions and processes are identified, and their relationships, are made explicit.4

• Stakeholder approach: This approach emphasises that the exploration of the enterprise need must arise from two perspectives: those of the stakeholders in the enterprise and those of managers of IT and networks. The stakeholder approach emphasises the importance of investing in relationships with those who have an interest in the stability of these relationships. These stakeholders are organisational units or individuals within the enterprise or, in the environment of the enterprise, whose decisions impact the way the enterprise is operated and managed. Of course, these stakeholders are impacted by the goals of the enterprise. The relations between them are characterised by simultaneous cooperation and competition. In other words, sometimes a stakeholder domain will demand independence from a recommended course of action, such as choosing between solutions. The interdependence between the parties is evident.5

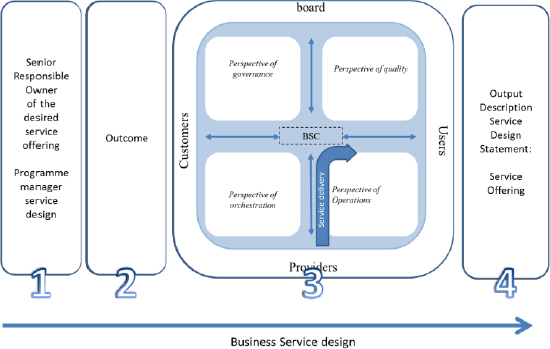

The BSD approach comprises four phases, initially surfacing need and service demand by identifying the senior responsible owner and secondly, the desired outcome of the service offering. The third phase is the analysis and synthesis using ‘the service constellation’ that is central in gathering the service design requirements then, the fourth phase, setting out the description of the final service design offering.

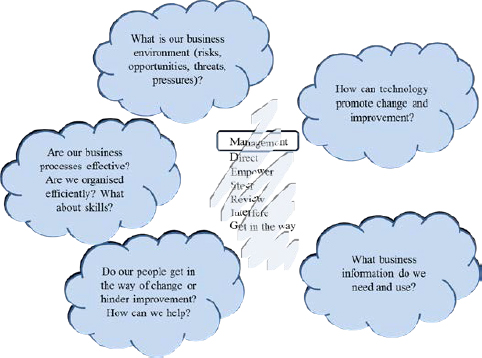

In following the BSD approach, you can work through the four phases using the canvas in Figure 2.3.

1. The senior responsible owner (SRO, a role title found in PRINCE2) is identified and the desired service offering is established. Most likely, this will be the role of the program manager for the service design.

Figure 2.3: Business service design approach

2. It must be clear what the outcome should be. To begin with, you need to have a solid understanding about the service outcomes and output.

3. At the heart of the BSD, there is the service constellation that supports the essential analysis and synthesis of the service offering requirements. The analysis and synthesis go through cycles. Steps in a cycle are:

a. Establishing stakeholders and their need or responsibility

b. Understanding service transactions

c. Understanding needed resources, risks and compliance

d. Choosing instruments for agreement. Finally, the output is translated into the SDS. After the analysis and synthesis, using the service constellation described in section 2.3.3, there are a number of steps you must take before you can compose the elements of the service design into the SDS.

2.4.1 Need and senior responsible owner

The SRO should have a position at the Board/GM level and must be responsible for the commission of a Gateway review of a major project, a survey or a feasibility study, or a complete service design. In this way, we can position the BSD as the overall business architectural transaction.

Someone within the enterprise is responsible for service offering delivery. Depending on the size and type of enterprise, who (manager or team) or what (department or several organisational units), the responsibility will be defined differently. This responsibility is often called service offering management (SOM).6 SOM focuses on the customer and the type of product and/or services they need. Activities that SOM oversees are:

• customer base and need

• service offering

• creation and delivering needed services

To understand the dynamics of the SOM, the enterprise is explored from two perspectives: the perspective of the stakeholders of the service offering and that of management of the enterprise and networks in general, and service delivery specifically.

Stakeholders will be identified from the perspective of those who are responsible that services come to fruition (or even come to an end as we see later) and are maintained. Stakeholders differ in every enterprise and in every service, that you would like to design.

Often a senior responsible service owner has many questions:

• Is this service the one I really need?

• Does the service fit my required outcomes?

• Should I invest in it?

• Can I minimise risks?

• How to involve all the essential stakeholders?

• Will the service add value?

• Can we control costs involved?

• What are the costs?

• and a hundred more…

As you can see most thoughts often do not focus on the ‘how’ of the service but on the impact and the consequences the service has in the larger scheme of things.

2.4.2 Business service coordination: I think therefore I am

For analysis and understanding purposes, and for the purposes of the BSD, it is necessary to identify someone that takes this delegated role and overall responsibility. This entity is the business service coordination (BSC) role. The BSC can be an individual or an organisational unit in the enterprise and in some cases even a virtual role.

Often the representative of the SRO is positioned in an organisational entity, which also takes decisions about sourcing and managing business information. Often, this role is created when the enterprise has outsourced functions (most frequently IT) and needs to retain knowledge to manage suppliers effectively. In the UK, this is often known as the intelligent customer function. Sometimes, this ‘intelligent customer’ function is called the retained organisation and the design of business services using IT can be part of it.

In many enterprises, you will find that there is no direct relationship between the different stakeholders. Often, a responsible function or agent is placed between the main stakeholders. It is impossible to identify all the specific characteristics of the responsible functions or agents without sound knowledge of the enterprise. BSD is an approach that assists with recognising the requirements and, if necessary, delegating appropriate responsibilities to a business service coordinator, or coordination team/role, so that an architectural service design can be qualified. And afterwards, the BSC role ensures that requirements are allocated to the appropriate roles in the enterprise so that the transactions are met.

2.4.3 Outcome and output must dictate behaviour

The direction of an enterprise, as put down in the mission and vision, answers questions, such as, ‘Where is this going? What business are we in? What business should we be in?’. The strategic directions are beacons to the development and design of business services. We must differentiate between output and outcome. The outcome is the focus of the mission and vision and should be the umbrella of all outputs that result from the different actions in the enterprise.

Output and outcome are not only ‘What you get’, they should be ‘What you expected and what you asked for’. This, of course, takes us back to warranty and fitness for purpose. Too often, the desired outcome is not fully articulated and all parties run off to their happy places and either wait for Christmas to happen, or start coding the reindeer before thinking about what Santa is going to put on the sledge.

Examples of questions to ask:

• What is the scope of the services?

• Where is the service/output delivered?

• When is the service/output delivered?

• Is the intended result(s) fully understood (output)?

• Is this service dependent upon other services?

• When does this service contribute to the mandated/desired output?

• When does this service contribute to the mandated/desired outcome?

• What additional factors can influence the success of this service?

It must be clear to all stakeholders what desired outcome and output should be. A clear description of output and outcome in the architectural service design process is imperative.

2.4.4 Service constellation

The stakeholder approach that is the basis of BSD thinking will help the SRO to understand the specifications of the new or adapted business services in relation to the conditions or opportunities. A Stakeholder is any group or individual who can affect, or is impacted by, the achievement of the purpose of the enterprise.

BSD focuses on the creation and delivery of business service. Hence the canvas in figure 2.3, which is called service constellation, must focus on the four essential groups that make this happen: board, customers, providers and users. Of course, behind and next to these four groups many more are trying to influence the process, output and outcome. So you make sure as Business Service Coordinator the SRO understands the central tensions and forces corresponding to the optimal business service.

Why do we call our image of the stakeholders and their perspectives the service constellation? To us it is similar to the night sky: there are patterns that people can see because they are told they exist (The Plough, Orion’s Belt) and there are some that you just cannot see no matter what you are told, and there are some you find for yourself.

The purpose of the service constellation is to ensure that the service deployed is the one that was desired, and that any design constraint issues (cost, perhaps, or security) were fully explored and understood before everyone signed up to development.

In the third step of BSD, you must navigate the service design constellation to establish service requirements. Seeing our service constellation for the first time can be mind boggling. It comprises many different elements that, when aggregated, help you to understand all the requirements that make up a service offering.

2.4.5 Service design statement

The result of your initial labours is the SDS, or service design statement. That is, a description of the IT intensive business services that you will take forward into the development of one or more services. After navigating the service constellation, you should have gathered all the information needed. Success depends on whether all the information is available to cover all the information in the design and development stages. From a business point of view, you must have all the business information needs to justify further investment and sign off.

Service constellation thinking facilitates extensively checking the service design offering and governing the full-service requirement. From a supplier perspective, you should probably work out some more details to complete the design stage and make the service offering feasible. However, the approach will uncover enough information in the design stage to influence design choices made and understand the capabilities needed. Therefore, at this phase we prefer to describe the output as a description of a service offering, rather than the design of the service offering.

BSC is the link for the enterprise with their customers and the providers of services. The objective of BSC is effective control of results of (insourced and outsourced) services by controlling demand as well as supply. For architectural service design and exploration, the BSC is the delegated service owner and the position where control will be managed. Figure 2.4 illustrates (in the centre) the most likely functions that will be undertaken and the complexity of the overall environment. The BSC can never take over the responsibility of the customer. However, their responsibility is delivering what is needed. The customer has final responsibility for ensuring that what is needed is fit for purpose.

Figure 2.4: The central role of the BSC

2.5 The Business Service Design session

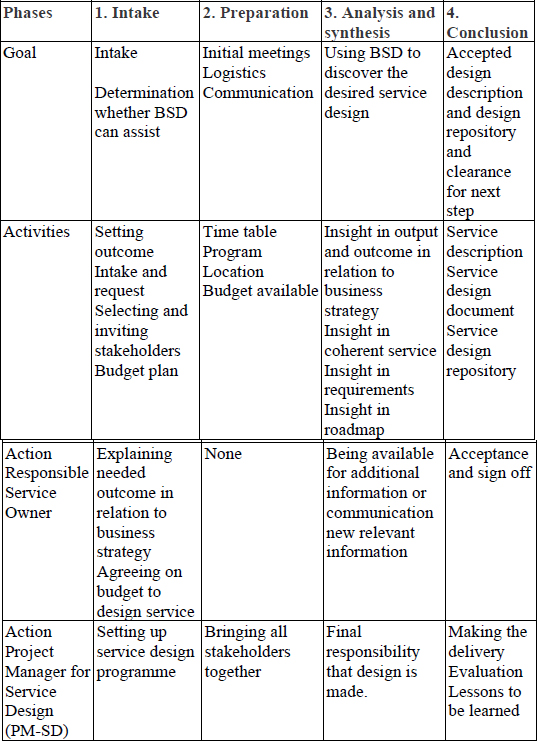

A BSD session generally comprises four phases: intake, preparation, analysis and synthesis and conclusion. Table 2.1 explains the different phases. Depending on the complexity of the service design you will find that the different phases take longer or more stakeholders need to participate. A golden rule does not exist. It depends on you as the leading practitioner, your experience and circumstances such as existing constraints. A constraint may be money (or lack of it), existing capabilities, perhaps even ambition.

Table 2.1: Four phases in a Business Service Design session

A graphical representation of the four phases is illustrated in Figure 2.5. Some people like words, some people like pictures. Whatever your preference, just be sure you cover everything!

Figure 2.5: Four phases in a Business Service Design Session

In the next chapter, we will begin by explaining the needs of the stakeholders and their dynamics.

_____________________

2 ITIL Service Design (2011), 2011 edition, Best Management Practice, Second edition, United Kingdom, Stationery Office.

3 See OCG Gateway, Bureau Gateway, Ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties and Major Projects Authority (MPA) UK Government.

4 See Shostack, G.L. (1984), Designing services that deliver, Harvard Business Review, January–february 1984, pp. 133–139.

5 See Freeman, R.E. (2010), Strategic Management, a stakeholder approach, first printing 1984, digital printed 2010. Cambridge University Press. Mastenbroek, W.F.G. (2005), Conflicthantering en organisatie-ontwikkeling. Proefschrift Leiden, vierde herziene druk, Samsom.

6 Tillman, G. (2008), The business oriented CIO; A guide to market-driven management, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, New Jersey.