Chapter 4

Collaboration Methods

Playbooks for Working Together

In 1959, Miles Davis entered the studio to record what would become the best‐selling, most popular jazz recording of all time: Kind of Blue. Even if you don't like mainstream jazz, you'll probably appreciate this album. The songs are approachable, the band sounds great, and every solo is a home run.

Davis was known for forcing his musicians to be spontaneous, so there were no rehearsals for this recording date. In fact, he gave the musicians the music to be recorded only as they entered the studio. Astoundingly, with only one exception, the first complete take of each tune for Kind of Blue was the one that got pressed on the album. In other words, they nailed it on the first try.

How is it possible for a group to come together and spontaneously create such a great work of art? What are the tools that allow for this type of exceptional collaboration? What can we learn from this group?

One of the keys to success in mainstream jazz improvisation is structure. That's right, contrary to popular belief, jazz musicians are not just making things up when they improvise. Instead, the players are well organized and follow common rules of engagement.

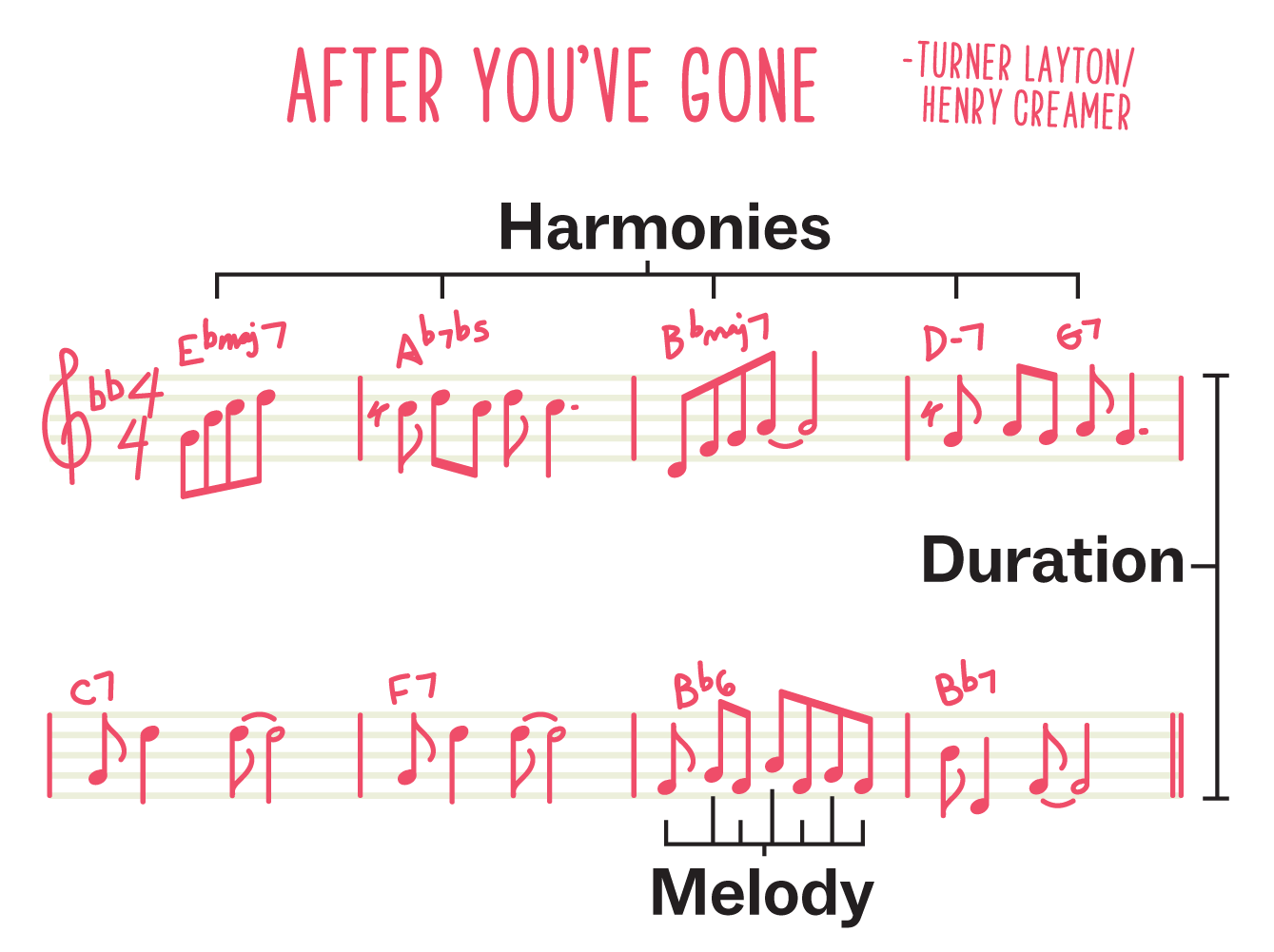

In particular, a “lead sheet” in jazz outlines the form of a tune. The lead sheet provides only three pieces of information: the melody, the harmonies, and the duration. That's it—everything all jazz musicians need to be able to perform as a group. The rest is made up on the fly, or “faked,” as they say. In fact, a collection of lead sheets in jazz is called a “fake book.”

Free jazz contrasts this approach. In free jazz, the improvisation is more total, even including the underlying form. There are no predetermined structures to follow. The result, to the average listener, is often abstract and obtuse. And without highly trained musicians, the music can fall apart quickly.

Now consider how your teams collaborate at work: Are you following the same lead sheet, or are you making up the form as you go? It turns out that much of workplace collaboration is improvised on the fly. Sure, we might have a meeting agenda, but an agenda is just a list of topics that doesn't clarify what the activities will look like. The structure of how we interact, decide, and make sense as a group is largely improvised.

Like free jazz, the results of meetings are often abstract, even chaotic, leaving people unclear, unfocused, and frustrated. We've all experienced the symptoms of bad meetings:

- A few people dominate the conversations

- Boring presentations lull participants to sleep

- Politics are played out in real time

- A lack of closure and actionable outcomes

- The result is all talk—and no artifacts or materials to show for it

But what if your teams, instead, were playing from the same page? What if instead of having an agenda and winging it, they used a proven set of methods to guide and direct collaboration? What if everyone understood the basic structure so that they could come in and play well together?

There's actually a wealth of these structures. We call them “guided methods.” They're simple to follow, easy to implement and customize, and deliver better results each time you put them to work. Best of all, they can supercharge your teams’ time collaborating together, whether in‐person or remote and whether synchronously or asynchronously.

Guided Autonomy

A common problem in team collaboration is what we call “blank canvas paralysis”: the group convenes with no plan on how to collaborate. Imagine a team standing in front of a whiteboard asking, “Now what?” Without a plan, the rules of engagement are improvised, often resulting in poor collaboration.

With collaboration methods, getting from point A to point B doesn't have to be a mystery each time. And they work without constraining creativity or the freedom to think outside of the box; instead, methods often have a liberating effect, giving teams the latitude to act and allowing their collective imagination to flourish.

Joe Lalley, founder of Joe Lalley Experience Design, told us:

What collaboration practices need the most improvement in your organization? How might introducing guided methods for deeper connections and better problem‐solving benefit your teams? What's one small thing you can try immediately to get more intentional about collaboration in your organization?

The Games Teams Play

Imagine playing a game with no rules. It wouldn't be fun, would it? It turns out that much of the enjoyment we get while playing comes from an agreed set of guidelines. When everyone knows how the rules work, the participation and involvement increase, and a group can really connect and be creative.

Collaboration methods provide “rules of engagement” for collaboration and allow team members to work together on equal footing, generating better results. And at the same time, methods make work more playful.

Collaboration methods, broadly defined, include any and all exercises, activities, games, frameworks, and techniques that thoughtfully direct team interaction. Think of them like sheet music for team collaboration: They provide a set of rules to follow and allow for creative freedom at the same time.

There are thousands of collaboration methods from various fields with many examples to point to. In each case, their function is the same: to make collaboration explicit and deliberate. Teams don't have to guess or react; they can all be on the same page.

Take, for example, the rituals from Agile practice, an approach for developing software that structures how teams priorities and focus on small chunks at a time. Formal methodologies like Scrum guide teams to collaborate in a very intentional way. Exercises such as “planning poker” simulate a game of cards, where participants have effort points to “bet” like chips in a round of poker. It literally brings game‐like interactions into solving problems as a team.

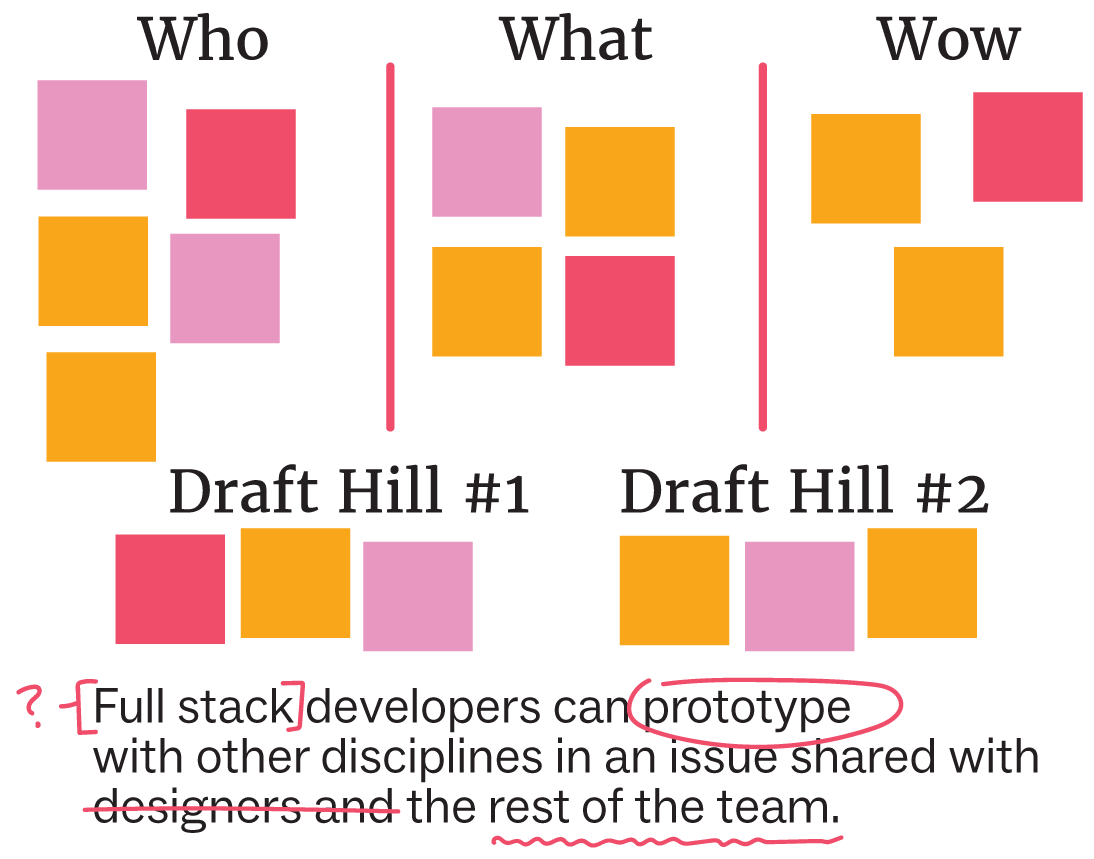

Then there's Hills, a collaboration method pioneered at IBM. It's a simple guided method to get a project team to identify and agree on a measurable problem statement. A Hill consists of three elements:

Who. The customers you're targeting to serve

What. The need they're trying to meet

Wow. How you'll differentiate from competitors by “wow‐ing”

IBM's Hills method guides team collaboration toward a shared mission statement for any effort.

The output of the exercise is a Hill statement:

“A sales leader can assemble a response team in under 24 hours without management involvement.”

“It should take no more than 13 minutes for a developer to build and run an app using third‐party APIs.”

Even complex problems, like determining business strategy, can benefit from a methodical approach. For example, the Business Model Canvas, developed by Alexander Osterwalder and the team at Strategyzer, is a collaboration tool for exploring different possible business models. Nine boxes represent the core elements of any business model, and an entire team fills them out one by one. This process is meant to ensure not only that all aspects of the business have been discussed, but also that everyone has been able to contribute on an equal footing.

The Business Model Canvas, developed by Alexander Osterwalder and the team at Strategyzer.

Methods like these are a key tool for collaboration designers to guide team collaboration in a very intentional way. They are your opportunity to make collaboration more deliberate. What's more, collaboration methods create fun and playful shared experiences. It's the moments we play together that really instill a sense of team connectedness and give rise to team empowerment, psychological safety, and strong relationships.

Structures and Patterns

The best collaboration methods share some basic common benefits, including:

- Helping include more voices for a diversity of perspectives

- Promoting imagination and creativity

- Making it easier to spot new patterns and opportunities

- Drawing out better results

- Saving time

Henri Lipmanowicz and Keith McCandless, the authors of The Surprising Power of Liberating Structures, use the term “microstructures” to describe the rituals and habits that shape the way we work with others:

“Consciously or not, microstructures are the way you organize all your routine interactions. They guide and control how groups work together. They shape your conversations and meetings.”1

On their own, these organizing patterns, however, typically don't allow for broad participation and for creativity to flourish. And bad habits of collaboration are all too common, like a few voices dominating conversations and not allowing for diverse perspectives to be heard. However, the authors offer a series of what they call “liberating structures.” These are methods specifically designed to shape collaboration in a way that “liberates” input from the whole group.

For instance, one of their collaboration methods is called “1‐2‐4‐All.” It's simple to use, and fits many different situations. The instructions are right in the title:

- First, participants reflect individually on the topic at hand (1 minute)

- Next, they get into pairs to share and compare each others thoughts (2 minutes)

- Then, groups of four share reflections and improve on their ideas together (2 minutes)

- Finally, the whole group re‐convenes and shares concepts with everyone (3 minutes)

One of the beauties of liberating structures is that they are largely self‐facilitating. That is, they are not only easy to use and approachable, they don't necessarily require a dedicated facilitator to put into action. Teams can agree to use liberating structures, and for the most part, put them into use right away.

The liberating structures framework consists of 33 methods, each representing a tiny shift in how we meet and relate to each other. Other examples include:

Generative Relationships. This technique helps a group understand how they work together. Participants first assess their team in terms of four attributes (Separateness, Tuning, Action, and Reason—or STAR) and then assemble a list of action steps to improve collaboration.

Heard, Seen, Respected (HSR). Teams can actively practice listening and having empathy for each other. Each person shares a story about NOT being heard, seen, or respected. The others listen and reflect on the patterns in the stories and what can be done to improve collaboration. HSR is particularly good for building trust and strengthening relational intelligence in a team.

TRIZ. This method is based on a single, foundational question: “What must we stop doing to make progress on our deepest purpose?” The team makes a collective list to discuss, and the result is often fun yet courageous conversations.

Of course, there are other sources of collaboration patterns as well. One of the best is the collection of activities gathered by Dave Gray, Sunni Brown, and James Macanuf008 in their book Gamestorming. Kursat Ozenc and Margaret Hagan also provide a range of techniques to improve collaboration in Rituals for Work. And one of our favorites is Hyper Island Toolbox, available for free online (https://toolbox.hyperisland.com/). The list goes on and on.

But don't be overwhelmed: A limited set of methods is all that's needed for your team to collaborate better. Your first step to using collaboration methods is adding one simple technique to your team interaction. Just know that there are many more resources out there that help you explore and adapt methods over time.

The net effect will be that the overall team‐member experience is improved. People become more engaged and are more likely to connect with each other when their work is guided with methods. Imagine every person and every team having a better experience and working more effectively. Just a small nudge in the right direction can have a dramatic effect on driving business results, which in turn, creates real ROI for your organization.

Combining Methods

You might be wondering, how you can get hundreds or thousands of people in an organization to learn and remember all these methods. It may seem exhausting at first glance.

One way to accelerate the adoption of these methods is to leverage existing frameworks. The LUMA system, for instance, helps teams find the right techniques to use for innovation by guiding collaboration designers in a structured way. LUMA has distilled their portfolio down to 36 of the most effective tools for innovation—the majority of them in common use. You don't need to know them all right away—a handful of them are enough to get started.

The LUMA system is organized into three key design skills: looking, understanding, and making.

Looking. Successful innovation requires curiosity and empathy for the people you serve. This begins and ends with the observation of people. The methods in the category reflect the careful investigation of the human problems you target and innovate around.

Understanding. Innovators must carefully understand the problems they want to solve with critical thinking and rigorous problem framing. Methods in the understanding category help teams do this together in a structured, repeatable way.

Making. Ideas alone have no value. Successful teams put their concepts into action by first representing ideas and then bringing them to life. Imagination, visual representation, and frequent iteration are required to make artifacts that embody your innovation, even in the earliest stages.

Each of these categories is divided into three subcategories, and each subcategory contains four innovation tools. This hierarchical model makes it much easier to identify the tools you need and then put them to use.

The LUMA System

Methods in the LUMA system can be combined and recombined into what are called recipes. In fact, this is its real power. These suggested sequences of individual exercises get the whole team on a path to a solution.

For instance, if a team has challenges aligning on near‐term priorities, there's a recipe that will get them on the same page. It consists of four steps that include input from the whole team:

- “Rose, Thorn, Bud” is an exercise that allows the team to reflect on the topic at hand from multiple perspectives.

- “Affinity Clustering” helps the team find patterns in its reflections.

- “Visualize the Vote” allows team members to highlight clusters that are most important to them individually and then find common patterns across the team.

- “Importance Difficulty Matrix” fosters a discussion around the concepts they agree to move forward with first.

Align a team on near-term priorities

Solicit opinions across a team in order to identify themes and transform them into a shared plan of action.

There are also recipes for strengthening the relational intelligence of a group. A recipe that we've found particularly effective helps teams gain empathy for someone else by learning about their life experiences. There are four steps to this recipe:

- Interviewing. Learn about someone using interviews. Create an interview guide and talk to someone who self‐identifies in a way that is different from you.

- Experience Diagramming. Create a “life line” by visually depicting the emotional experience of your interviewee to get a sense of it over time.

- Rose, Thorn, Bud. Together, visually codify the Experience Diagram so that you can see where positives, negatives, and opportunities lie.

- Alternative worlds. Leverage each other's different perspectives to help generate fresh ideas and shared understanding.

Gain Empathy for Someone Else by Learning about Their Life Experiences

But there's more to LUMA than just a way to organize methods. Even the name is meant as a mnemonic for solving problems together—a profound reminder of the fundamental behaviors at the root of effective collaboration: It calls for us to look carefully, understand deeply, make resourcefully, and adapt accordingly.

Taken together, these form the LUMA principle, which summarizes key actions and attitudes that need to be adopted—both individually and collectively. It's also a sequential process and a dynamic way of operating, in which various mixtures of looking, understanding, and making activities inform adaptive change.

Similar principles and lines of thinking can be found in other organizations. IBM is one of the more successful examples of leveraging the method of design thinking to affect organizational changes. Their Enterprise Design Thinking (EDT) program was built and rolled out over a decade.

Similar to LUMA, EDT offers a complete design thinking toolkit and activation plan. It was originally intended for internal use at IBM, but more recently, they've made it available to the general public and have started consulting clients.

Whether you develop your own set of playbooks, like IBM has done with EDT, or rely on a pre‐existing system, finding unique and appropriate ways to combine methods helps educate and scale across teams within an organization.

Making Collaboration Methods an Everyday Practice

Change rarely happens from the top down only; lasting transformation tends to work from the bottom up. Thus, in knowledge work, guided methods help activate better collaboration, interaction by interaction, on the ground level.

Like learning an instrument, the more you play the better you get. You have to break down things into smaller parts. You have to practice. This is a muscle you have to build within and across teams over time.

At first, your aim in applying collaboration methods should simply be to internalize the rules of play. Things might even be awkward at the outset, but once everyone on a team knows the steps and the process, it becomes fluid.

For example, you might want to build more empathy by using a team warm‐up before each meeting. We've found that using a short prompt to begin each interaction can help getting to know your teammates on a personal level. Try something like “What was your first job?” or “What's your favorite bad movie?”

The use of any one guided method like this by itself might seem inconsequential. But over time, as you add and by adding more and more, you'll be able to affect your team's culture in a deliberate way.

The idea is to create a series of “tiny habits,” a behavior change approach pioneered by BJ Fogg. His research shows that transformation happens best by taking baby steps. Tiny habits work by first finding a trigger event and then attaching the new behavior to it.

Fogg recommends using this statement to get started:

For example, if you want to build better habits around dental hygiene, you might try doing this: After I brush my teeth, I'll floss just one tooth. From there you'd move to two teeth, three teeth, and so on. Eventually flossing all of your teeth after you brush becomes an effortless, almost unconscious action.

This approach to behavior design is proven to work for several reasons. The most important of them is time. Making sweeping, team‐wide change takes a lot of effort and time. Just thinking of all of the materials to create and training to deliver for a team to change all at once can crush initiatives. There's something daunting about making large changes that sets them up for failure. Instead, taking incremental steps helps overcome inertia in a realistic way.

Setting up a series of tiny habits your team can practice to improve how they collaborate is a small, achievable goal. It's the kind of change that adds up to transformation over time. And simple guided methods are modular enough that you can start right now—tomorrow in your next team meeting, for instance. With practice, the team will improve over time, cultivating for collaboration each time they gather.

Meta, for instance, broke down activities for team collaboration into manageable chunks in its Facebook Think Kit toolkit for rapid collaboration, ideation, and problem‐solving across teams. It's a series of exercises rooted in design thinking and customer‐centric methods. Each activity has simple instructions and worksheets to help teams follow along visually.

Exercises can be used on their own or combined with “suggested pairings” to achieve goals. The Think Kit allows teams to make creative thinking a habit, one exercise at a time—from setting a North Star together to running a pre‐mortem to creating a storyboard.

Now it's your turn to try it with your team. Start small by introducing just one new activity to bring about change. For instance, if you want to make sure certain voices don't always dominate and that everyone has a chance to speak, you might introduce “popcorning” as a way to take turns. With this method, the last person to speak picks the next, until everyone has had a chance. This helps establish a safe environment where everyone's input is valued.

Find the prompt to invoke popcorning and make a statement around it, for example, “After we initiate feedback gathering in a meeting, we'll use popcorning to regulate turn taking.”

Repeat that behavior until it feels natural for your team

Then introduce another practice that you want to adopt. This might be something like adding short reflections at the end of each meeting using three categories of input in the format “I liked..., I wish..., I wonder...” as taught at the Stanford dSchool. Soon you'll have whole recipes of methods.

Finally, keep in mind that expert collaboration designers are available to guide the habit building. Good collaboration design goes beyond one‐off interactions and helps teams accumulate successful practices over time.

Once you no longer have to think about adding methods, you'll start customizing them. Every team is different, and your playbooks need to be relevant and appropriate to your context. Soon, you'll be jamming from your own lead sheets.

Note

- 1 Microstructures & Design Elements, Liberating Structures, https://www.liberatingstructures.com/design-elements/.