13 Explaining path dependence in boundary work for internal and external innovation

The role of corporate collaborative spaces

Introduction

Following the approach of open innovation (Chesbrough et al., 2006) aiming at the systematic hybridization of internal R&D resources with external resources, companies have recently opened up their boundaries to external partners (e.g., customers, suppliers, research centers, universities, and local community) who may provide complementary resources in joint innovation projects. At the same time, consistent with the evidence provided by studies on contextual and social determinants of creativity (Perry-Smith & Shalley, 2003; Shalley & Gilson, 2004), many companies are promoting inter-functional projects and innovation teams. Thus, they have re-designed some of their internal workspaces to foster collaboration, personal interactions, spontaneous socialization, and, thus, divergent thinking and creativity (Jakonen et al., 2017; Leclercq-Vandelannoitte & Isaac, 2016; Waber et al., 2014). As a result, companies have started to embrace collaborative spaces (CSs) and practices with the dual function of promoting internal innovation with internal employees (e.g., R&D and other company departments) and external innovation with a diversity of external stakeholders such as entrepreneurs, freelancers, prosumers, or the civil society at large (Spreitzer et al., 2015). The aim, usually taken for granted, is that these spaces will make both internal and external boundaries more blurred and consequently more easily to tear down, obtaining a positive effect on the organization’s innovation capabilities. However, there has been little research on corporate CSs and boundary work, and even less is known about the role of such spaces for tearing down internal and external organizational boundaries. The aim of our study is to explore these research questions by focusing on the use of CSs for internal and external innovation at the organizational level.

In this research, we argue that the innovation projects that aim at spanning internal and external boundaries may come with a price that has been little considered so far in the literature. In particular, the new organizational practice promising to tear down internal and external boundaries simultaneously could also generate the unexpected consequence of path dependence in internal and external innovation projects, respectively. Given that boundaryless spaces are set up within bounded organizations, employees may find themselves managing increased heterogeneity in innovation projects such as dealing simultaneously with the contrasting collaboration goals, interests, and backgrounds of colleagues from other functions and of their customers and suppliers. On the one hand, this may provide new work experiences helpful for tearing down collaboration boundaries and increase creativity in innovation projects. On the other hand, it may also generate a set of defensive strategies aimed at maintaining power and identity at the organizational level (Santos & Eisenhardt, 2005). Specifically, because boundary breaching does not come without costs as it requires a large amount of efforts and taxes attention and relational resources (Ungureanu & Bertolotti, 2018), it may negatively affect employees’ perceived ability to manage the ensuing complexity. The paradoxical consequence could be that a practice developed to tear down boundaries could make them re-emerge. Consequently, the benefits of corporate CSs could be different from what originally imagined.

We investigate our research questions through an exploratory study conducted in a multinational company operating in the food industry, which has recently created a CS inside its premises with the purpose of promoting innovation projects with internal and external stakeholders. The case reported in this chapter is one of the first examples of such space in Italy, inspired by a design thinking approach. The implications of our study discuss how and why existing and new boundaries may re-emerge as organizations try to tear them down by creating boundaryless CSs. We highlight the role of emergent constraints in terms of attention and relational efforts that boundaryless spaces trigger within bounded organizations.

Theoretical framework

The rise of CSs

In the past few decades, we have witnessed an increased scholarly and managerial attention to how spatial and material realities can affect how organizations operate and trigger changes in employees’ behaviors (Clegg & Kornberger, 2006). Although the first studies on organizational space focused on how the physical characteristics of the space where people ordinarily work affect behaviors (e.g., Davis et al., 2011; De Croon et al., 2005; Oldham & Rotchford, 1983), a more recent scholarly conversation has started to focus on the phenomenon of CSs (coworking, incubation spaces, social innovation centers, fab labs, cultural centers, technology parks, etc.). In the digital organization era, CSs respond to the needs for new organizational knowledge practices, increasing flexibility, and faster responses in the environment. It is interesting to notice that these spaces have been often referred to as “third places.” Accordingly, the CS allows workers to experience and reproduce organizational practices even if they are not part of an organization (Cnossen & Bencherki, 2019).

Till now, potential benefits of CSs have been mainly targeted to knowledge workers, gig workers, and micro start-ups. For knowledge workers and gig workers, these spaces may be an affordable workspace which may offer visibility (Merkel, 2019), legitimacy, and a sense of community (Garrett et al., 2017), thus contributing to avoiding the risks of isolation and job insecurity as well as to building a professional identity (Petriglieri & Obodaru, 2018). Similarly, CSs may satisfy the need for efficiency of start-ups and their desire to join a network of professional relationships which might sustain and accelerate their business ideas (Capdevila, 2015; Spinuzzi, 2012). The systematic hybridization between the internal competences and the external heterogeneous competencies provided by the different actors who work in the CS may sustain creativity, contributing to reducing inertia and avoiding the mere replication of past solutions (Gavetti & Levinthal, 2000).

Organizational workplaces as “third places”: The boundary paradox

It is noteworthy that recently CSs have also started to inspire companies to design more open internal workspaces with physical characteristics (e.g., architecture and layout) and functioning logics that recall “third places” (e.g., flexible use of space and time; calls for ideas or innovation projects). Accordingly, extant research on CSs distinguishes between external, commercial coworking spaces (Bouncken et al., 2016) and internal, corporate CSs, i.e., CSs within large corporations such as internal (open) coworking spaces, corporate fab labs, or corporate hybrid spaces (de Vaujany et al., 2019; Leclercq-Vandelannoitte & Isaac, 2016). However, to the best of our knowledge, extant studies have focused mainly on external CSs and the few empirical evidence on corporate CSs is mainly explorative. Nevertheless, extant literature recognizes that the use and the practices that construct these spaces can be very different (Bouncken et al., 2018; Jakonen et al., 2017). Thus, for instance, organizations may adopt the model of the CS to communicate aspects such as openness to external stakeholders (e.g., customers, supplier, and local community), social responsibility and non-territoriality with respect to internal conflicts between organizational functions (e.g., R&D, marketing, and finance) (Elsbach, 2003; Elsbach & Pratt, 2007; Leonard, 2013). Given the importance for organizations of managing their internal and external boundaries, we argue that such new trend entails an unexplored paradox interesting to study.

On the one hand, setting up CSs inside organizations aims at breaking down different types of boundaries, for instance, those between different organizational functions to stimulate the exchange of knowledge and co-creation, by making hierarchies flat, team collaborations more spontaneous, and individuals more willing to participate in team work (e.g., Capdevila, 2013; Colleoni & Arvidsson, 2014; Furnari, 2014; Gandini, 2015). On the other hand, such aspirations may often be at odds with the very nature of organizations. According to Santos and Eisenhardt (2005), boundaries reflect the very essence of the organization, the demarcation line between an organization and its environment, and the nature of boundaries can explain the success or failure of an organization. Boundaries necessarily relate to what is inside and outside the organization. The demarcation strategy chosen by each organization allow for efficiency, power, competence, and identity claims (Comeau-Vallée & Langley, 2019; Langley et al; 2019; Santos & Eisenhardt, 2005). To refer to this paradox, we refer to the concept of “boundary work.”

The general definition of “boundary work” refers to any effort to create, maintain, shape, or shift boundaries affecting groups, occupations, or organizations (Ashforth et al., 2000; Gieryn, 1983; Helfen, 2015; Lamont & Molnár, 2002). It is noteworthy that boundary work may be both about breaching and defending boundaries. The studies of Comeau-Vallée and Langley (2019), Quick and Feldman (2014), Meier (2015), Kellogg (2009), and Ungureanu and Bertolotti, (2018) highlight the possible coexistence of these opposite forms of boundary work within the same context: professional groups can create, maintain, or reconsider interprofessional and occupational distinctions in order to build new, more balanced social orders, oscillating between collaborative and defensive attitudes, and using available tools for such purposes.

The questions that rise are thus related to how organizations reconcile their need for internal-external demarcation and the attempts to create boundaryless spaces within their premises. Particularly, we are interested in understanding how a CS may help an organization manage internal and external boundaries, and whether they actually reach the purposes for which they were set up, considering their goals to become more innovative, on the one hand, and the need to maintain distinctiveness (i.e., efficiency, power, competence, and identity claims), on the other hand.

Context and method

Context: Larnia Group’s design thinking CS

We conducted our case study in the headquarters of an industrial group that we fictitiously name Larnia, a leader in different segments of the food market. The Group excels in production and distribution strategies and invests in continuous product and process innovation. In the last years, Larnia has also started to embrace the paradigm of open innovation by building a CS in the headquarters. The purpose of the CS was to foster innovative cross-functional and multi-stakeholder projects guided by the design thinking approach. The CS was created following a “smart urban” style. It occupies a former factory building that was owned and operated by the Group. It is an open space, with minimalist design furnishings, often created with recycled materials. The space is available to all employees of the company, and also welcomes outsiders (e.g., customers, business partners, consumers, masters’ students, and researchers) who are invited to the design thinking sessions by the organizers of each session. Each group is called upon to solve a need or to optimize a product, or a process, within projects that last for different periods of time, from several weeks to more than a year. The space is managed by employees from Larnia’s R&D department.

Research design, data collection, and analysis: A grounded theory approach

We conducted a field study in Larnia and adopted a grounded theory research approach that entails iterations between data collection, data analysis, and theorizing (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). We conducted 30 semi-structured interviews. The semi-structured interviews were conducted face-to-face and have an average duration of one hour. The interviews were organized around a set of open-ended questions following an interview protocol on the management and use of the CS and the issues arising from its design and use. According to the grounded theory approach, the protocol was continually adjusted and changed during interviews, as to leave the interviewee free in providing us opinions and interpretations. Simple open question included: “Describe the CS”; “Why and when do you enjoy the CS”; “Describe a project in which you participated in the CS”; “Describe the use you have made or made of CS.”

Moreover, 23 interviewees were internal to the organization (coming from seven different functional areas) and seven interviewees were external to the organization, including actors from other organizations like external consultants and masters’ students. All interviews were fully recorded and transcribed. We obtained more than 1,000 pages of field notes that were used to elaborate the grounded model.

The data were analyzed following the grounded theory methodology and three phases of recurrent coding: open, axial, and selective (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). We used the Nvivo software to perform all the stages of coding. During open coding, we focused on the CS itself (features and design) and on the interpretations and uses that informants made of the CS. As we progressed through coding, it became obvious that boundaries were a recurrent theme in the data so we started refining our coding scheme to capture as many distinctions as possible regarding the ways in which informants talked about space and boundaries (e.g., how work boundaries were moved, overcome, or created in the exchange between users of the CS). It also emerged that informants often made distinctions between internal and external use of the CS, so we started thinking about internal and external boundary work, after going from data to theory and back, we came up with the three aggregate categories (described later) further refined our grounded model.

Findings

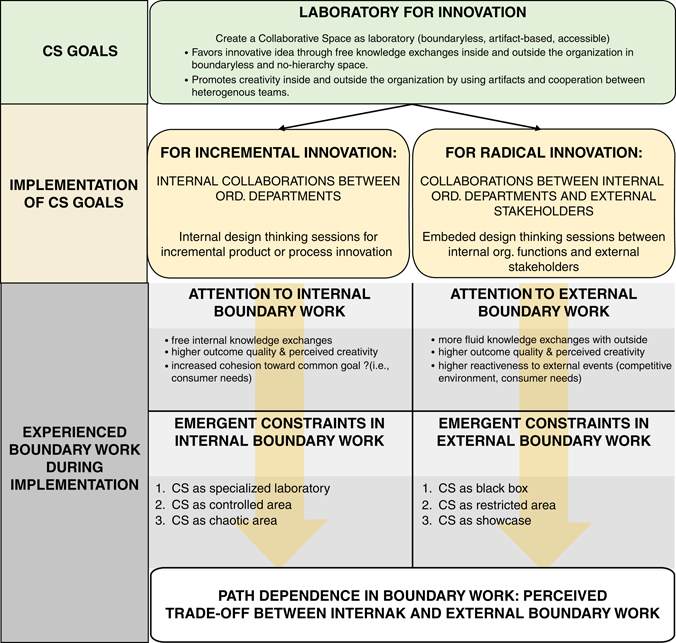

The model that derives from the data analysis (Figure 13.1) identifies three dimensions that concur in explaining the use of the CS for boundary work within Larnia: (1) CS goals, (2) implementation of CS goals, (3) experienced boundary work during implementation.

CS goals

To meet the innovation needs highlighted by the corporate strategy, Larnia decided to create a space in line with the open innovation paradigm, encouraging the search for innovation beyond organizational boundaries, and at the same time by promoting inter-functional projects with a high degree of diversity which aimed at fully exploiting the know-how and internal company skills. The CS, therefore, sets itself clear and defined objectives: to foster the generation of innovative ideas through the free exchange of knowledge between people with highly diverse backgrounds and to promote creativity inside and outside the organization.

The informants explained to us that Larnia designed the CS as a laboratory for innovation guided by the design thinking approach, a human-centered approach to innovation that draws from the designer’s toolkit to iteratively connect the needs of different stakeholders such as customers, consumers, business partners, with the possibilities of technology, and the requirements for business success (Brown, 2008). According to the design thinking paradigm, the sessions are organized in such ways that individuals with different backgrounds and/or cultures take part and feel engaged and fully motivated to bring a personal contribution, taking advantage of the enthusiasm that co-generation of ideas and contamination brings along (Brown, 2008).

During the data analysis, we found that all informants ideally referred to the CS as a laboratory in which it was possible to experiment new forms of aggregation and collaboration on inter-functional projects. According to the informants, the space as a laboratory had to be adaptive and located in a central location of the company for easy access. Additionally, it needed to be informal and equipped with tools to generate easy-to-use artifacts and prototypes that could further encourage the co-generation of ideas between people with very different skills and backgrounds. Physical features such as open spaces, bright colors, modular design, and informal workstations were expected to stimulate and favor free knowledge exchanges inside and outside the organization by tearing down organizational functions and hierarchies. Also, by adopting the design thinking approach, Larnia aimed at promoting creativity inside and outside the organization by encouraging co-creation and joint decision-making inside the CS.

The goal of CS on internal-external boundary work was therefore to help users break down barriers (in terms of goals, hierarchy, or skills) and modify their work boundaries, in order to use a new approach to innovation based on co-creation:

One has to come here with his skills […] and not asserting his authority with his own competence compared to what others are telling you. […] A free and informal space can facilitate both relations with colleagues from other departments and collaborations with people from outside the organization.

(Informant 3, internal)

Implementation of CS goals

We found that despite the goal of using the CS as a laboratory for simultaneous internal and external innovation, Larnia’s CS generally hosted two different types of innovation sessions with different approaches: sessions for incremental innovations that featured internal collaborations between organization departments and sessions for radical innovations that featured collaborations between internal organizational departments and external stakeholders.

The design thinking sessions for incremental innovation with internal collaborations between organization departments were often organized by the members of the R&D department who invited the members of other organizational departments such as Marketing, Quality, Sales, and HR to participate in design thinking sessions organized for a well-defined project. The purpose of the design thinking sessions was often to generate innovative ideas about how to improve existing products or solve pre-existing problems to make product development and product-to-market processes more efficient. All sessions organized aimed at generating exchange and contamination of contents coming from different organizational areas, and at sharing different approaches and best practices for carrying out work activities.

I must say that it was very useful to explore the most important issues and misunderstandings that occur when different business areas interact, not so much to solve the problem but to bring out what was going on and what was wrong with the interactions in a process flow. […] It all happened with people inside Larnia and an external coach (Design Thinking coach) […] we had very different business backgrounds.

(Informant 1, internal)

Sessions for radical innovation are organized as collaborations between internal organizational departments and external stakeholders. These were typically composed of employees from internal departments – e.g., R&D, Marketing – who often launched the challenge and invited to the team external stakeholders such as retail clients, consumers, students, suppliers, and other stakeholders from the public arena as well, for instance, bloggers and journalists. The goal was to develop new idea for new products development. Our informants from Larnia often referred to this type of collaboration as “embedded,” as shown in the following excerpt:

at the time I was in charge of the 3D Printing project and I worked on a first project, we did a first embedded in Italy made by four master’s students […] they were the outsiders, plus five people from Larnia. […] The goal was not to develop a product but a new Business Model, so understanding how to make money from this innovation.

(Informant 2, internal)

Experienced boundary work during implementation

Experiences about boundary work in the CS refer to the way people actually used the CS to shape and shift their work boundaries, both internally and externally. In particular, we found that the CS afforded similar positive experiences (i.e., affordances) when used internally and externally, and different negative experiences (i.e., constraints) for internal and external innovation projects. Importantly, we show that the different goals that Larnia mobilized with respect to internal and external innovation (incremental and radical innovation approach, respectively), even if implemented in the same space, required different work method. Therefore, they mobilized users’ attention and resources differently such that path dependence was created – i.e., innovation problems were constrained by users’ subjective interpretations into pre-existing schemes available to the organization, shaping how internal and external collaborations were implemented, and generating a trade-off between the two.

Free knowledge exchanges internally and externally

Users declared that their experiences with the CS were coherent with their expectations about the CS. The analysis of the interviews suggests that through its affordances in terms of being boundaryless, artifact-based, and accessible, the CS promoted free knowledge exchanges between different business functions which informants deemed important and difficult to experience elsewhere. For instance, many informants referred to the furnishings of the space for the most part modular and mobile, so that the users involved can change the space according to emergent needs at each session of use. Being able to change the space according to one’s needs takes into account the individual needs for control of the work area and on the knowledge exchanges that occur inside of it (Dul et al., 2011; Elsbach & Pratt, 2007). The space also consisted of a large kitchen where it was possible to cook, experiment new ideas, create prototypes, or just sit with other session participants over coffee. A large monitor connected to a computer system was also available for content sharing in the standing area of the kitchen. Informants often referred to this set up as facilitating informal knowledge exchanges and tearing down boundaries in the organizational hierarchy, across departments and when meeting with external stakeholders such as clients, customers, or consultants:

Very, very satisfying, but why? Because […] it was nice to have different people around the kitchen table, some of the Quality or other folks who are absolutely not in my world, to reflect for three months on this channel here, right? We took time every week for three hours, to reflect, that is to just close all the rest and say – well now I concentrate on this thing here.

(Informant 3, internal)

The same aspects were mentioned when we asked informants about external boundary work. For instance, thanks to the design thinking sessions in the CS, knowledge exchanges for radical innovation in collaboration with external stakeholders seemed more fluid, intense, and dynamic than in other more traditional contexts. Widening the boundaries of the space to outsiders meant changing the organizational boundaries and therefore achieving a higher degree of cross-fertilization, which informants argued it was beneficial in terms of innovative and creative ideas.

Higher outcome quality and perceived creativity internally and externally

Informants often mentioned the physical features of the CS such as furniture, plants, windows position, quality of light, sounds and colors which they associated to creativity, more productive knowledge exchanges and innovation. For instance, sofas, armchairs and chairs, and small tables were easy to transport and adapt depending on the space that users intended to create to facilitate brainstorming activities either about radically new product features (external projects) or about improved product features (internal projects). In addition, the space offers many useful objects for constructing artifacts and prototypes (e.g., post-it, Lego blocks, pens, colored pencils, sheets, glue, scissors, and string) necessary during the design thinking sessions, but made available to any user at any time. Referring to these aspects, our informants declared that they perceived themselves and other colleagues as more creative, and also the outcome of the projects in the CS was defined as more creative and innovative.

[output] Let’s say that it was very satisfying from the creative point of view. Some things were totally inapplicable from the point of view of reality due to cost or other reasons, but good ideas came out.

(Informant 7, internal)

Creative outcomes were also mentioned when informants discussed external boundary work. Bringing outsiders into the company provided solutions that were deemed “out of the box” and thus more “original, fun and creative.”

Increased cohesion toward a common goal internally and higher reactiveness externally

Living in the CS and participating in design thinking sessions increased users’ perception of cohesion both internally and externally. Internally, informants reported feeling closer to those people inside the organization with whom they worked in the CS, and abler to set differences apart in order to focus on the company’s needs, instead of the needs of their organizational departments. Externally, not only introducing external stakeholders into the company makes the research for customer needs more effective and the response to the needs of the suppliers targeted and efficient, but it also involves important improvements in terms of speed of response to these needs. Informants often reported that having external actors within the space allowed them to identify external needs more promptly and therefore to improve their response time to market. For instance, the more they collaborated with external stakeholders in the CS, the abler they were to overcome differences in goals and mindsets and the more important the definition and achievement of a common goal became for all of them:

Embeddeds with customers are interesting because also for the customer this is a different space, so surely you win over the fact that it is different, in the sense all the people who come here to see it are affected because there is a choice, a break-with-the-past choice.

(Informant 5, manager of collaborative space)

However, it is interesting to notice that although users identified similar affordances of the CS for internal and external collaboration, they continued to distinguish between incremental projects conducted internally and radical projects conducted with the help of external stakeholders.

Emergent constraints in internal boundary work

In addition to affordances for both internal and external boundary work, our evidence also highlights emergent constraints. Because each type of boundary work (i.e., incremental and radical innovation) was more effortful than initially expected, and required more resources, they became path dependent, i.e., individuals felt constrained by previous goals and experiences to treat the two separately. Consequently, informants experienced a trade-off between the ability to focus on internal boundary work and the ability to perform external boundary work.

CS as specialized laboratory

During interviews, informants often talked about the CS as if it were a specialized space that applied exclusively the design thinking method. For this reason, they often perceived the space as an overly specialized laboratory to which they were invited whenever design thinking sessions were organized. For instance, informants highlighted that the space was not inhabited by the employees according to their spontaneous needs and impulses for creativity, but rather driven by the fixed agenda of the R&D department. For this reason, many of them reported that they felt put down about participating in projects that they “didn’t really feel as their own,” where participation was “not really open and spontaneous” or which outcomes were “not fully understandable from the beginning.”

CS as controlled area

Although it was designed as a free space for anyone in the company, the CS was systematically perceived as belonging to the R&D area. As informants explained, this was because employees from the R&D department had set up the space in an area that previously belonged to their department and were actively managing the site and all the activities organized there. Another reason why the CS was stably associated to the R&D department was the fact that most design thinking sessions were centered around incremental projects (e.g., product improvement topics), which were seen as “R&D people’s thing.” As a consequence, not only did people outside R&D perceive the CS as owned by R&D, but also people working in R&D identified the space as theirs and instrumental to achieving their work objectives. These dynamics further strengthened the identity of the space like a silo and not as an active and integral part of the organization:

At the end of the workshop we asked them (Facility management department) to let us use it a little more, and after a while, we had colonized the space on a permanent basis […] We wanted this to become a space for the whole organization but I know people think it’s our toy, they often come in and say, we went to the R&D people’s area.

(Informant 6, R&D, internal)

CS as chaotic area

Finally, space is experienced by internal employees as always moving and constantly transforming, and consequently also deemed chaotic and noisy. For instance, the space does not seem to adapt to the need for systematic collaboration, structured communication, or individual task concentration, thus reinforcing the idea that the space was set up for group projects and workshops that required less systematic collaboration, for instance, collaboration projects with external stakeholders aiming at radical innovation.

Emergent constraints in external boundary work

Concerning external organizational boundary work, informants complained that external boundary work turned out to be much more complex than expected and, thus, also much more effortful.

CS as black box

As already seen for the internal boundary work, the CS was defined as a black box when it came to interact with external stakeholders for radical innovation projects. In particular, there was little visibility about which external stakeholders entered the CS, when and why. This was also caused by the fact that external stakeholders were always invited by internal employees to enter the CS, and it never happened that a project challenge was launched by external stakeholders, as it never happened that external stakeholders substituted internal employees in creating the project team. As a consequence, informants often lamented that each project with external stakeholders became a black box on which the rest of the organization had little knowledge and control.

CS as restricted area

We also found that projects with external stakeholders were seen by users as restricted and opaque to the rest of the organization. The bureaucratic procedures for access and the barriers to overcome in order to enter the CS made the CS an isolated space also for outsiders. For instance, clients, consultants, and students also had the perception that the space was the propriety of the R&D department. In fact, to access the CS inside Larnia, it was necessary for external stakeholders to have an appointment set with the space manager or with other internal employees. In addition, not only did they have to register at the reception, but an internal member of the organization had to personally pick them up at the reception desk. This procedure was deemed long and onerous and discouraged outsiders from using the space, especially outside the collective design thinking sessions.

CS as showcase

Differently from what happened with internal boundary work, we also found that the CS was used as a showroom for external stakeholders, especially clients and public opinion leaders such as food bloggers and journalists. For instance, whenever working together on open innovation projects was difficult to accomplish, Larnia used the CS as an impression management tool for external stakeholders. This evidence is in line with prior studies on CSs which highlight that such spaces are used for visibility, at times aimed at the organization’s employees or at external clients. In the latter case, the space is used as a showroom for showing products and services to customers (de Vaujany et al., 2019).

Our informants often referred to critical incidents in which managers throughout the company brought suppliers and customers to visit the space in order to impress them using the CS innovative aspect, and thus to convey the image of Larnia as an innovation pioneer, but without allowing them to get immersed in the CS and use it as a generative lab for radical innovation ideas. This was often considered a superficial and inappropriate use of the space that needed to be corrected with time, as to allow for more generative and immersive activities to take place.

In conclusion, the emergent constraints to internal and external boundary work were perceived as complications with respect to initial innovation goals and led to a general perception of the need to increase efforts and attention to both types of boundary work.

Path dependence and CS: Trade-offs between external and internal boundary work

Managers of the CS repeatedly argued that the CS was a critical space which was difficult to animate with shared projects and populate with people with different background. The fact that the space was experimented as having different functions from the ones initially envisaged triggered users’ and space managers’ increasing efforts to make the CS more congruent to the initial goals of Cs as laboratory for innovation. Interestingly, although they dreamed of a CS that blurred internal and external boundaries and encouraged free co-creation, users continued to distinguish between the need to engage in incremental innovation with other internal functions and the need to open up to outsiders to perform radical innovation (i.e., strengthening path dependence). Importantly, as they struggled with the affordances and constraints generated by each type of innovation, users also explained that they needed more resources in terms of time and attention to perform each type of innovation boundary work successfully. Consequently, internal and external boundary works were perceived by our informants as competing and encroaching upon each other:

I have participated in different types of design thinking, with external students and internal ones, with coaches and with clients on different topics, not only on products. If there are external people, you are a little more open to contamination, but if we stay among ourselves in the end it is easy to fall into the same ways […] However, when there’s many of us from different departments and we’re not that used to working together, it’s better not to have also external people because then the complexity just explodes.

(Informant 8, internal)

Based on this evidence, we concluded that in Larnia, there was a perception of path-dependent boundary work for innovation. Believing that internal boundary work was most suitable for incremental innovation projects and that external boundary work was most suitable for radical innovation projects, directing resources in one direction could come at the expense of the other. Importantly, the perception that internal and external innovations were path dependent was at odds with the initial goal of creating a CS that allowed to do both indiscriminately. This translated in an opposition between the goal of implementing the CS as a laboratory for free internal and external exchanges and the actual experiences that users had of the space – i.e., specialized, controlled, and chaotic area for incremental innovation with internal stakeholders and a black-boxed, restricted showcase for radical innovation with external stakeholders. In other words, what users had meant as a simplification triggered additional complications in Larnia’s management of innovation projects. Specifically, our informants reported that the multiplication of the CS’s affordances and constraints with respect to Larnia’s initial goals led to the perception that the space was becoming increasingly complex and heterogeneous, and that interacting in the CS required increasing relational efforts which could be difficultly sustained internally and externally at the same time.

Discussion and concluding remarks

In this chapter, we have investigated how people experience corporate CSs adopting the perspective of organizational boundaries. Because such spaces are basically designed and implemented to encourage creativity and collaboration among internal members and between the organization and the external stakeholders (de Vaujany et al., 2019; Jakonen et al., 2017), we have focused on the boundary work that corporate CSs require to their users.

Our findings show that corporate CSs imply demanding boundary work both internally and externally. In fact, because companies have traditionally demarcated boundaries (both inside among organizational units and outside with the external environment), the creation of an internal CS open also to external actors requires tearing down internal and external boundaries. However, we have shown that one of the main reasons why this occurs is related to the fact that individuals that set up and use CSs have pre-existing beliefs about how and with whom they can collaborate for innovation purposes. Our evidence suggests that people involved in corporate CSs (both the company’s employees and external stakeholders) are aware that a large amount of boundary work will be required and, as a matter of fact, they experience positive consequences in terms of knowledge exchanges, work quality, and increased cohesion. However, our findings also suggest that several unanticipated constraints may emerge both in internal boundary work and external boundary work. We have shown that a CS may generate high expectations about the possibility of tearing down boundaries and facilitating free knowledge exchanges. The design thinking approach adopted in the CS had the aim of mixing internal and external stakeholders in highly innovative projects and giving this way space to new ways of collaborating. However, we documented that individuals’ pre-conceptions about innovation may push them to use the CS differently than initially intended: as a place for incremental innovation with members of other organizational functions, on the one hand, and as a place for radical innovation with external actors, on the other hand. Individuals’ cognitions thus condition the way the CS is being used, and thus generate discrepancy between initial goals (CS as laboratory) and experienced implementation (specialized, controlled, and chaotic area for incremental innovation and black-boxed, restricted area and showcase for radical innovation).

Interestingly, we show that the efforts devoted to face and reduce such constraints tax too much people’s relational and attentional resources so to generate a trade-off between external and internal boundary work. Enacting the former encroaches upon the ability to perform the latter and vice versa.

Taken together, our findings offer both theoretical contributions and practical implication.

On the theoretical standpoint, we propose the perspective of boundary work and more specifically the perspective of internal and external boundary work to better understand the avant-garde practice of corporate CSs in terms of functioning, benefits, and drawbacks, as well as in terms of perception and experience of individuals involved in such spaces. In doing so, we contribute to the scant extant research on internal, corporate CSs both adding empirical evidence and suggesting a theoretical framework helpful to appreciate the diversity and differences between external and internal CSs, for instance getting a light on why and how an internal innovation hub may effectively work (or does not work) as a makerspace (for employees) and showroom (for customers) at the same time (de Vaujany et al., 2019). In fact, a boundary work perspective seems particularly appropriate to study and comprehend CSs in corporations, where the work is less precarious than for a freelancer and, as result, joining the CS is not a free choice, the interactions may be not voluntary and the CS is an “intentional attempt to make the encounters matter businesswise” (Jakonen et al., 2017). Moreover, large corporations traditionally have marked boundaries in terms of internal functioning and in how they relate with their external environment. Although the creation of a corporate CS can be conceived as a means to tear down boundaries, we show that the risk of cognitive path dependence in innovation projects, and the (likely underestimated) existence of a “double work,” both internal and external, runs the risk of affecting the overall ability of such spaces to attain the goals for which they were first created. Literature on boundary work has not explicitly differentiated between internal and external boundary works but this distinction is key in our model.

Also, literature on innovation has been concerned with path dependence from a technological standpoint, and it has only recently started to explore cognitive determinants such as perceptions and interpretations (Garud et al., 2010; Langlois & Savage, 2001; Thrane et al., 2010; Tripsas & Gavetti, 2000). As a matter of fact, path dependencies in innovation processes are often defined as change process constrained by the prior technologies adopted by an organization (i.e., economies of scale and technological interrelatedness), the pre-existing knowledge at the organizational level (i.e., core competencies), the constraints at the institutional level, which result in self-reinforcing innovation dynamics (Andersen & Howells, 1998; David, 1985; Dosi, 1982; Garud & Karnøe, 2003; Leonard‐Barton, 1992; Nelson and Winter, 1982). The effect of cognitive frames as a trigger of path-dependent behaviors such as the one mentioned earlier is emerging as a stream of research (Kaplan & Tripsas, 2008; Tripsas & Gavetti, 2000). Yet, it is rather surprising that the empirical processes by which cognitions shape innovation processes and create path dependence have not been systematically scrutinized (Garud et al., 2010; Thrane et al., 2010; Tripsas & Gavetti, 2000). For instance, Cohen and Levinthal (1990) argue that “lock-outs” from new technologies or innovation processes potentially occur because individuals are conditioned by their pre-existing knowledge and competencies (see also Thrane et al., 2010; Tripsas & Gavetti, 2000).

Our study reaffirms that cognition in general, and in particular interpretations about which innovation problems are more suitable for external vs. internal collaborations, plays a key role in how individuals perform boundary work. By distinguishing between potential trade-offs between internal and external path-dependencies, and by looking at the role of CSs in path dependence, we also contribute to this literature. We suggest that to understand the role of CSs for innovation, it is paramount to investigate the interpretations that organizational members attach to internal and external boundaries, respectively, and analyze the collaboration goals that they set for themselves at the light of these interpretations. Hernes (2004) proposes that organizational actors would act toward three different types of boundaries: physical boundaries (related to physical structure and formal rules that regulate people’s actions and interactions), social boundaries (related to social bonding and identity) and mental boundaries (related to concept and central ideas). The perceptions of unbalance between internal and external boundary work could be influenced by the need to engage differently in the three above boundaries management mechanisms when dealing with internal and external dimensions. Future studies could further explore the relationship between different types of boundary, boundary perceptions, and path dependence.

Our work is not, of course, without limitations: We have conducted a single case study based on interviews with space managers and users. Future studies could consider different settings (for instance, settings in which the CS is managed with a different approach from the design thinking methodology) or provide evidence with different data support, for instance, observations of collaboration instances occurring inside CSs. Although we performed observation in the CS, our study relies primarily on individuals’ self-reports because we were interested in understanding their perceptions and expectations, rather than their actual behaviors. Future studies may compare and contrast users’ cognitions and their actual behavior, for instance, their behavior during design thinking sessions in the CS.

As far as practical implications are concerned, our study suggests to companies engaging in the creation of internal CSs to take into consideration the relational and attentional resources for internal/external boundary work, without assuming that the design of a “boundaryless” space will naturally diminish the need to put them in place. Conversely, managers should provide space users resources in order to manage the boundary work, thus avoiding constraints and trade-offs in internally and externally boundary work. Our study suggests that to foster internal and external collaboration, different types of resources, as well as different types of physical spaces, could be required. Thus, a reasonable insight is that optimizing both collaborative activities at the same time may be challenging, and that path dependence should be taken into consideration when setting up collaborative arrangements for innovation projects.

References

Andersen, B., & Howells, J. (1998). Innovation dynamics in services: Intellectual property rights as indicators and shaping systems in innovation. CRIC Discussion Paper No. 8, University of Manchester.

Ashforth, B. E., Kreiner, G. E., & Fugate, M. (2000). All in a day’s work: Boundaries and micro role transitions. Academy of Management Review, 25(3), 472–491.

Bouncken, R. B., Clauss, T., & Reuschl, A. J. (2016). Coworking-spaces in Asia: A business model design perspective. Conference: Strategic Management Society Special Conference, Contextualizing Strategic Management in Asia: Institutions, Innovation and Internationalization. Chinese University of Hong Kong, 10–12 December.

Bouncken, R. B., Laudien, S. M., Fredrich, V., & Görmar, L. (2018). Coopetition in coworking-spaces: value creation and appropriation tensions in an entrepreneurial space. Review of Managerial Science, 12(2), 385–410.

Brown, T. (2008). Design thinking. Harvard Business Review, 86(6), 1–9.

Capdevila, I. (2013). Knowledge dynamics in localized communities: Coworking spaces as microclusters. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2414121 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2414121. SSRN 2414121.

Capdevila, I. (2015). Co-working spaces and the localised dynamics of innovation in Barcelona. International Journal of Innovation Management, 19(3), 1540004.

Chesbrough, H., Vanhaverbeke, W., & West, J. (Eds.). (2006). Open innovation: Researching a new paradigm. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Clegg, S., & Kornberger, M. (2006). Space, organizations and management theory. Malmö, Sweden: Liber.

Cnossen, B., & Bencherki, N. (2019). The role of space in the emergence and endurance of organizing: How independent workers and material assemblages constitute organizations. Human Relations, 72(6), 1057–1080.

Cohen, W. M., & Levinthal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 128–152.

Colleoni, E., & Arvidsson, A. (2014). Knowledge sharing and social capital building. The role of co-working spaces in the knowledge economy in Milan. Unpublished Report, Office for Youth, Municipality of Milan.

Comeau-Vallée, M., & Langley, A. (2019). The interplay of inter- and intraprofessional boundary work in multidisciplinary teams. Organization Studies, https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840619848020.

David, P. A. (1985). Clio and the economics of QWERTY. The American Economic Review, 75(2), 332–337.

Davis, M. C., Leach, D. J., & Clegg, C. W. (2011). The physical environment of the office: Contemporary and emerging issues. In and G. P. Hodgkinson, & J. K. Ford (Eds.), International review of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 193–237). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

De Croon, E., Sluiter, J., Kuijer, P. P., & Frings-Dresen, M. (2005). The effect of office concepts on worker health and performance: a systematic review of the literature. Ergonomics, 48(2), 119–134.

de Vaujany, F. X., Dandoy, A., Grandazzi, A., & Faure, S. (2019). Experiencing a new place as an atmosphere: A focus on tours of collaborative spaces. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 35(2), 101030.

Dosi, G. (1982). Technological paradigms and technological trajectories: A suggested interpretation of the determinants and directions of technical change. Research Policy, 11(3), 147–162.

Dul, J., Ceylan, C., & Jaspers, F. (2011). Knowledge workers’ creativity and the role of the physical work environment. Human Resource Management, 50(6), 715–734.

Elsbach, K. D. (2003). Relating physical environment to self-categorizations: Identity threat and affirmation in a non-territorial office space. Administrative Science Quarterly, 48(4), 622–654.

Elsbach, K. D., & Pratt, M. G. (2007). The physical environment in organizations. Academy of Management Annals, 1(1), 181–224.

Furnari, S. (2014). Interstitial spaces: Microinteraction settings and the genesis of new practices between institutional fields. Academy of Management Review, 39(4), 439–462.

Gandini, A. (2015). The rise of coworking spaces: A literature review. Ephemera, 15(1), 193–205.

Garrett, L. E., Spreitzer, G. M., & Bacevice, P. A. (2017). Co-constructing a sense of community at work: The emergence of community in coworking spaces. Organization Studies, 38(6), 821–842.

Garud, R., & Karnøe, P. (2003). Bricolage versus breakthrough: Distributed and embedded agency in technology entrepreneurship. Research Policy, 32(2), 277–300.

Garud, R., Kumaraswamy, A., & Karnøe, P. (2010). Path dependence or path creation? Journal of Management Studies, 47(4), 760–774.

Gavetti, G., & Levinthal, D. (2000). Looking forward and looking backward: Cognitive and experiential search. Administrative Science Quarterly, 45(1), 113–137.

Gieryn, T. F. (1983). Boundary-work and the demarcation of science from non-science: Strains and interests in professional ideologies of scientists. American Sociological Review, 48(6), 781–795.

Helfen, M. (2015). Institutionalizing precariousness? The politics of boundary work in legalizing agency work in Germany, 1949–2004. Organization Studies, 36(10), 1387–1422.

Hernes, T. (2004). Studying composite boundaries: A framework of analysis. Human Relations, 57(1), 9–29.

Jakonen, M., Kivinen, N., Salovaara, P., & Hirkman, P. (2017). Towards an economy of encounters? A critical study of affectual assemblages in coworking. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 33(4), 235–242.

Kaplan, S., & Tripsas, M. (2008). Thinking about technology: Applying a cognitive lens to technical change. Research Policy, 37(5), 790–805.

Kellogg, K. C. (2009). Operating room: Relational spaces and microinstitutional change in surgery. American Journal of Sociology, 115(3), 657–711.

Lamont, M., & Molnár, V. (2002). The study of boundaries in the social sciences. Annual Review of Sociology, 28(1), 167–195.

Langley, A., Lindberg, K., Mørk, B. E., Nicolini, D., Raviola, E., & Walter, L. (2019). Boundary work among groups, occupations, and organizations: From cartography to process. Academy of Management Annals, 13(2), 704–736.

Langlois, R. N., & Savage, D. A. (2001). Standards, modularity, and innovation: The case of medical practice. In and R. Garud, & P. Karnøe (Eds.), Path dependence and creation (pp. 149–168). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Leclercq-Vandelannoitte, A., & Isaac, H. (2016). The new office: how coworking changes the work concept. Journal of Business Strategy, 37(6), 3–9.

Leonard, P. (2013). Changing organizational space: Green? Or lean and mean? Sociology, 47(2), 333–349.

Leonard‐Barton, D. (1992). Core capabilities and core rigidities: A paradox in managing new product development. Strategic Management Journal, 13(1), 111–125.

Meier, N. (2015). Collaboration in healthcare through boundary work and boundary objects. Qualitative Sociology Review, 11(3), 60–82.

Merkel, J. (2019). ‘Freelance isn’t free.’ Co-working as a critical urban practice to cope with informality in creative labour markets. Urban Studies, 56(3), 526–547.

Nelson, R. R., & Winter S. G. (1982). An evolutionary theory of economic change. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Oldham, G. R., & Rotchford, N. L. (1983). Relationships between office characteristics and employee reactions: A study of the physical environment. Administrative Science Quarterly, 28: 542–556.

Perry-Smith, J. E., & Shalley, C. E. (2003). The social side of creativity: A static and dynamic social network perspective. Academy of Management Review, 28(1), 89–106.

Petriglieri, J. L., & Obodaru, O. (2018). Secure-base relationships as drivers of professional identity development in dual-career couples. Administrative Science Quarterly, 64(3), 694–736.

Quick, K. S., & Feldman, M. S. (2014). Boundaries as junctures: Collaborative boundary work for building efficient resilience. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 24(3), 673–695.

Santos, F. M., & Eisenhardt, K. M. (2005). Organizational boundaries and theories of organization. Organization Science, 16(5), 491–508.

Shalley, C. E., & Gilson, L. L. (2004). What leaders need to know: A review of social and contextual factors that can foster or hinder creativity. The Leadership Quarterly, 15(1), 33–53.

Spinuzzi, C. (2012). Working alone together: Coworking as emergent collaborative activity. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 26(4), 399–441.

Spreitzer, G., Bacevice, P., & Garrett, L. (2015). Why people thrive in coworking spaces. Harvard Business Review, 93(7), 28–30.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research techniques. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Thrane, S., Blaabjerg, S., & Møller, R. H. (2010). Innovative path dependence: Making sense of product and service innovation in path dependent innovation processes. Research Policy, 39(7), 932–944.

Tripsas, M., & Gavetti, G. (2000). Capabilities, cognition, and inertia: Evidence from digital imaging. Strategic Management Journal, 21(10–11), 1147–1161.

Ungureanu, P., & Bertolotti, F. (2018). Building and breaching boundaries at once: An exploration of how management academics and practitioners perform boundary work in executive classrooms. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 17(4), 425–452.

Waber, B., Magnolfi, J., & Lindsay, G. (2014). Workspaces that move people. Harvard Business Review, 92(10), 68–77.