Implementation, Problem Solving, and Decision Making in Cultures

Despite apparent differences in complexity of decision problems across cultures, the core issues are essentially the same—fulfillment of human needs, protection of the individual, promoting group survival, and maintenance of community norms and standards

—Mann et al. (1998, p 326)

Introduction

Decision making is fundamental to the job of a manager. Socialization and differing business environments, however, can influence both the decision-making process and the choices. With significant growth in international interactions, it is now more important than ever to understand how people from different nationalities make decisions. Top management team (TMT) member orientation and decision-making style is generally not consistent across national boundaries. Values and beliefs, as they are characterized by national culture, have the potential to influence managerial decision making. Managers now need to know not only about the culture of the person they are interacting with but also about their personality, behavior, communication styles in conflict situations, demographics, and lifestyles.

Not only corporate giants but middle-sized companies are also going global to achieve economies of scale. Managers must not only make strategic choices but also restructure organizations, functions, and processes. Flatter organization structures have led to the growth of globally scattered matrix teams. Today’s cross-cultural teams have to work cross functionally as well as cross-culturally. In the current scenario, teams—marketing, virtual, research and development, production, and product development—are essentially cross-cultural in nature. Team members represent different cultures, each with their unique set of behavioral norms and ability to create, transmit, store, process, and transfer internally defined critical information.

Cross-Cultural Work Group

A cross-cultural work group or team comprises members belonging to different geographic, ethnic, and national boundaries. Team members differ from one another with respect to cultural, mental, and social programming. Groups may be defined in terms of cross-cultural work groups and multinational teams and task groups and may be formal or informal, localized or dispersed, and of short-term or long-term appointment.

|

A typical scenario at the workplace While interacting in a cross-cultural group work, group members of a typical cross-cultural team initially encountered problems relating to language. Members spoke in Japanese, Korean, French, and German. Though translators were utilized, the process took time and proved costly. Then the group resolved to use English as the language of group communication. This created a fresh set of problems. The Japanese could hardly communicate in English, and the Germans’ English was rough and heavily accented. The French were not keen on speaking English at all. The Koreans were aggressive and resisted participation in the conversations. The working of the team was problematic because the group could not sacrifice national preferences for international commitment. However, the group acknowledged that conflicting styles were creating obstacles and that there was a greater need for cooperation. Finally, an international consultant was called to help the group create synergy among themselves. |

Team Development in a Cross-Cultural Work Group

There is a growing realization that individual technical brilliance is no longer the only requisite for effective work performance in independent team assignments. Cross-cultural synergy needs to be realized to bring about desired results.

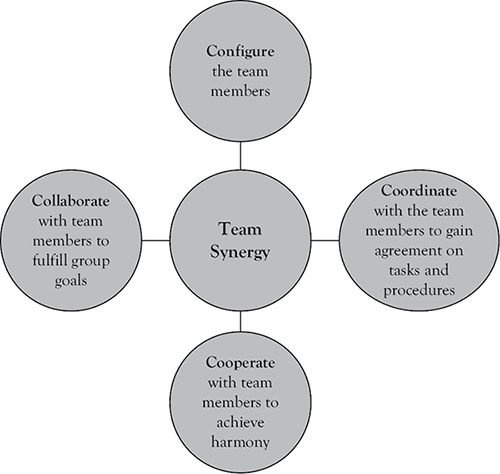

Team development in a cross-cultural work group essentially takes place in four stages (see Figure 7.1 in the following text).

Figure 7.1 Stages in multicultural team development

Configure

The first stage is the group constitution stage. Members come together for the first time and examine, through their particular cultural lenses, the composition of the team and task requirements. The stage can include culture shock, language problems, and ambiguity. Members realize that they are different from each other in terms of nationality and culture. The members, through their particular cultural lens, examine the fit between the members’ culture of origin culture of residence and the task at hand.

Coordinate

The second phase involves gaining agreement on tasks and procedures. Task allocation is determined, taking into consideration the members’ complementary and universal skills. Members agree on best times to schedules meetings, language of instruction, frequency and mode of interaction, decision-making roles and responsibilities, hierarchy, leadership issues, prioritizing of short-term and long-term plans, and behavioral norms.

Cooperate

The third phase involves building rapport among team members through the exercise of effective interpersonal skills. Barriers to communication include dominance by an individual or a major subgroup, deliberate politeness, and exclusion of certain members. Research reveals that members often adapt their behaviors, behaving not only as they would in their home culture but in the other cultures of the work group also. Crucial outcomes of this phase include trust, cooperation, and communication. Ethnocentric attitudes are explored so that disruptions and misunderstandings are minimized. Teams are quite susceptible to breakup at this juncture.

Collaborate

The fourth phase is reached when the work group begins to function like a work team. The hallmark of this stage is risk-free (no member feels discriminated against) communication. Synergy (group output is more than individual output) replaces groupthink (tendency of individual group members to align their views with the group leader), and the team is focused on task completion.

The following communication variables can impact the level of collaboration achieved:

• Frequency of communication among group members

• Existence of a common language of communication

• Frequency of exchange of task-related information

• Manner in which conflicts are resolved

• Demonstration of positive nonverbal behaviors

• Degree of engagement in informal conversation

• Effectiveness of persuasion and reasoning among members

• Methods of communication

|

Tapas Mohapatra, Implementation Coach at McKinsey & Company, Mumbai When communicating with others, I focus on the “richness” of my idea. I prepare the content thoroughly so that I come across as prepared. It is important for me to pay respect to people belonging to a culture different from mine. This is evident in the small gestures that I make when I am conversing with them. |

It has been noted that diversity creates greater bottlenecks in intraorganization and domestic cultures than in multicultural teams. Employees belonging to the same cultures are often reluctant to recognize internal conflicts within an organization. For instance, there is greater synergy between English-speaking Americans and Canadians than between Anglophone and Francophone Canadians.

Norms of Decision Making in Eastern and Western Societies

There are stark differences between Eastern and Western cultures as to who makes the decision, who is consulted, who gives inputs, and even bases on which decisions that are made. For example, the Western way of decision making has been described as objective, rational, and impersonal, in contrast to the Eastern way of deciding, which is subjective, emotional, and personal. There has also been a strong debate with respect to the positive and negative effects of TMT, demographic heterogeneity on intervening processes, as well as team processes. At one end, assertions have been made that TMT heterogeneity paves the way for an enhanced level of brainstorming, variety of strategies, problem-solving methods, and consequently, better decision making. On the other hand, management scholars contend that heterogeneous teams take too much time to resolve contentious interpersonal issues for the team to focus much on effective decision making. Recent studies have examined the impact of various demographic variables on TMT effectiveness, including TMT tenure, educational background, functional background, and impact on corporate profitability (Grecke and House 2012).

Literature on cross-cultural communication reveals that typically people from all cultures tend to be overconfident in life and those from the Eastern societies even more so. While some cultures are perceived to be more risk averse than others (Western societies), there are other cultures that embrace risk as a way of life (some Asian countries). Some cultures value decision making by consensus (Swedes, Japanese), while others prefer to avoid the use of groupthink altogether. Barriers also arise when fatalistic cultures feel uncomfortable planning for the long term.

|

A study exploring the attitudes of German and Indian students toward strategic aspects of problem solving found that Germans were more vocal and control oriented and committed fewer errors than the Indian students. The Germans were accustomed to making decisions themselves, unlike the Indian students who relied on others’ support to arrive at a decision. Similar results were found in studies examining differences in decision-making and problem-solving processes (weighing alternatives, accepting trade-offs, information choices, etc.) and the use of audiovisual aids among different cultures. The study is not clear as to which employees were more productive—the Germans or the Indians. |

Even cultures in the same geographic zones often differ from each other in their problem-solving and decision-making processes. The Cartesian model, (derived from the French philosopher Descartes), is the basis for French rationalism and the inductive logic that guides French decision making. As a result, the French tend to consider all aspects before arriving at a decision. However, their actions tend to be more subjective and less concrete. They like to explore various options and do not mind having multiple meetings to finalize a market strategy or business decision. They like to demonstrate their intellect by customizing customer solutions. French managers like to present individualistic ideas to demonstrate their intellectual capacity. Decision making is made by the heads of departments, while the middle and the lower managers administer the decisions. Thus, decisions are usually implemented by those who had no say in the original decision making. French control is also tight at various levels to compensate for low levels of commitment from the implementers.

The Danish on the other hand are methodological, pragmatic, and less engaged in their approach to decision making; when they make a report, it is less emotional and more down to earth. They speak in a clear-cut manner and are decisive in their thought process. They usually prefer short meetings to decide strategic issues. The decision makers are usually the implementers, and therefore their commitment level is higher. Control is less tight among the Danes due in part to the concept of responsible autonomy. The Danes gauge effectiveness by teamwork and cooperation as well as the output obtained, than a mere demonstration of their superior intelligence. Actionable goals and realistic implementation plans are strongly emphasized, rather than intellectual debate and argumentative discussion.

In China, the strong influence of the local as well as regional government is evident in the decision-making process. Organizations such as the Ministry of Commerce, People’s Bank of China, State Administration of Taxation, China Banking Regulatory Commission, and State-Owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) are extremely important to foreign investors in operational and financial matters. Experts recommend that investors must exercise patience and diplomacy in their dealings with these agencies especially when seeking permits or approvals.

Japanese problem-solving methods involve the use of jidoka—a method by which problems are resolved as soon as they arise through detailed analysis and discussion so that they do not recur. Continuous improvement or kaizen eliminates anything that is a variation of the standard. Decisions are rarely made at Japanese meetings. Meetings are held either to convey information or to convey a decision already made by the senior management. The idea of nemawashi (roots of a tree) implies that discussions and debates are to take place before the meeting actually takes place. Implicit to this idea are the concepts of honne and tatamae where what one publicly states (tatamae) is often vastly different from what one personally thinks (honne). Decisions are reached through the process of consensus building and is concerned with the preservation of wa (group harmony).

|

In a decision-making situation, an American manager described that the Japanese took days and sometimes weeks to arrive at a decision. The strong need of the Japanese for affiliation was paramount for preserving old relationships and cultivating new ones. Reaching a consensus was a painfully slow process; however, they made up for it by speeding up the implementation. The manager found that in comparison, the Chinese were quicker in deciding, but lacked implementation effectiveness. They liked to exercise power and control to influence the direction of decision making. The Americans were analyzers who analyzed situations and identified possible solutions through a structured decision-making process. Thus, the Americans could work around the prevailing power structure to enforce decision making, unlike the Chinese and the Japanese who are careful not to disturb the prevailing power structure. |

India is a hierarchical society, and positional power is thus considered valuable. Organizational roles are strictly defined, with the attitude of the superior often paternalistic toward the employees. Managers ensure that they know about the family and health aspects of their employees apart from purely professional contexts. Indians do not generally react positively to criticism and tend to withdraw from group meetings when confronted with it. The culture is relationship as well as group oriented; therefore, preserving harmony is important. In terms of decision making, managers and subordinates feel comfortable consulting with each other during important decision-making meetings. Indians are also not averse to risk-taking in business decision making. Decisions are mostly made on the basis of the collective good of those impacted by the decision rather than on the strength of sheer numbers and percentages.

To conclude, cross-cultural group workings involve the intensive use of information and communication technologies, especially for virtual teams that have few if any opportunities for face-to-face interaction. The challenge before multicultural executive teams is twofold. First, they must develop a situational analysis of the business problems confronting the organization and involve the various members in expressing their ideas about desirable solutions, and arrange and rearrange the information for best results. The second challenge would be to quickly resolve differences among team members and spend the team’s valuable time and energy on problem solving. The cultural intelligence of the manager is critical to both processes.

Summary

1. Flatter organization structures have led to the growth of matrix teams scattered globally.

2. In current business environments, teams of all types are essentially cross-cultural in nature.

3. Decision making is fundamental to the job of a manager. However, socialization and differing business environments influence both the decision-making process and the choices that managers make.

4. There is a stark difference between Eastern and Western cultures on certain aspects of decision making, such as who makes the decision, who is consulted, decisions and solving problems, and the values and interests.

5. Even cultures in the same geographic zones often differ from each other in their problem-solving and decision-making processes.

6. Managers now need to know not only about the culture of the person they are interacting with, but also about their personality, behavior, communication styles in conflict situations, demographics, and lifestyle.

7. Team development in a cross-cultural work group essentially takes place in four stages—configure, coordinate, cooperate, and collaborate.

8. The challenge before multicultural executive teams is twofold: one, to develop a situational analysis of the business problem confronting the organization and two, to efficiently resolve differences among themselves and spend time on problem solving. The level of cultural intelligence of the manager is essential to these processes.

Key Terms

• Socialization

• Diversity

• TMT