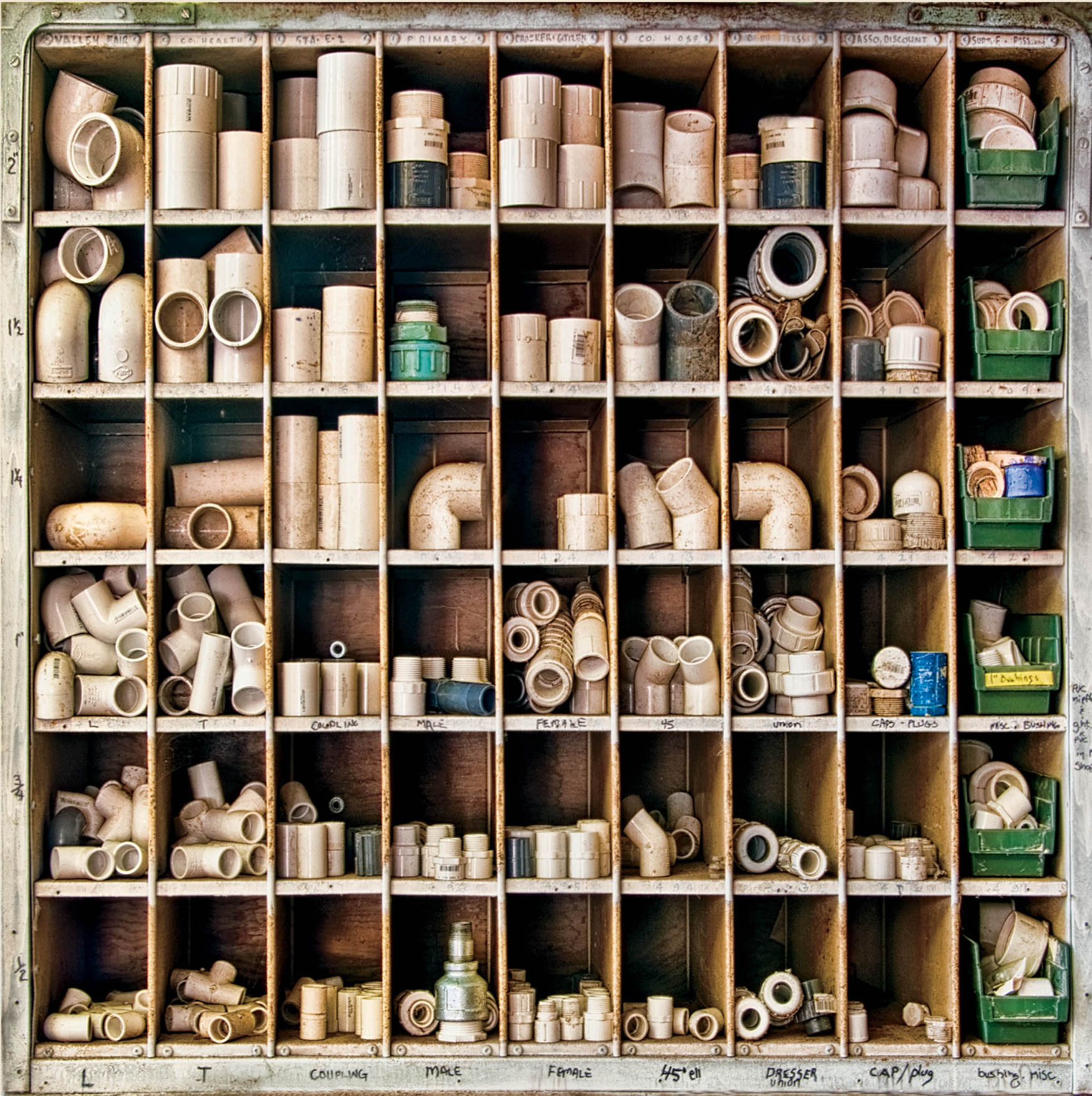

All Squared Away—This grid of plumbing parts, found in a farming toolshed at a Zen monastery near San Francisco, yammered for my attention because of its obvious regularity. There are a lot of rectangles and squares in this composition!

If you’re dealing with a lot of squares in a composition, it’s a good idea to put them into a square boundary. That’s why this image is presented as a square. Looking at the overall composition, it is a grid of rectangles. What’s the one thing that should happen with a grid of rectangular shapes? It is important that the right angles appear as 90˚ angles; the shapes can’t be distorted. This should not be a problem if the camera is positioned smack-dab in the middle of the height of the grid with the focal plane exactly parallel to the grid (see “Moving the Camera Slightly Makes a Big Difference” on page 61).

The sad fact of photographic life is that things are never perfect or ideal. The reality was that when I inspected this image on my studio monitor, some of the rectangles in the grid were bowed and no longer perfectly square. This took some work to correct in Photoshop, but eventually everything was “all squared away.”

Why go to so much trouble with a grid of rectangles full of plumbing supplies? Because the entire visual point of this composition is to relate the outer framing square to the inner grid.

Nikon D300, 18-200mm Nikkor at 38mm, five exposures with shutter speeds ranging from 1/10 of a second to 2 seconds, each exposure at f/10 and ISO 200, tripod mounted.

Combine lines and some right angles, and pretty quickly you get to rectangles and squares. (For the record, a square is just a rectangle where all the sides are the same.)

I know! We’re bypassing the humble—but mighty—triangle. But, don’t worry! The triangle gets its due on page 75.

Rectangles play an especially important role in composition. It’s hard to overstate. With few exceptions, every photographic composition is bounded by a rectangle.

Being bounded by a rectangle has extremely important implications; of course, the rectilinear spaces within a composition have important considerations on their own. Taking this all together—the bounding rectangle, internal rectangles, and the relationships of the internal and bounding rectangles to one another—there is a considerable and valuable tangle of compositional opportunities and considerations involving rectangles in almost every image.

Furthermore, in addition to the bounding rectangle and rectangles internal to an image, there is one other rectangle we need to consider: the rectangle made by the camera’s focal plane.

Just a bit ago, I mentioned exceptions to the rectangular framing. One exception is the tondo, a piece of round art, which you can read about further starting on page 70. In regard to unusual framing and proportions, you might also check out the discussion on “Busting Into and Out of the Frame” starting on page 66.

Understanding Borders and Frames

As a generalization, the camera captures an image in a rectangular shape and most digital sensors are rectangular or square. However, a print or reproduction of a photograph—while often rectilinear—is sometimes manipulated into a variety of shapes.

Most often, the rectangular shape that was captured by the camera becomes the rectangular frame bounding the image both in its native capture and in a reproduction or print rendering.

When making a photograph, the precise geometric relationship of the camera’s focal plane to the subject matter of your photo is not fixed until the shutter is released. The way you decide to establish this visual relationship has important consequences (see “Moving the Camera Slightly Makes a Big Difference” on page 61).

A study of rectangles starts with acknowledging the crucial, but often understated, role of “framing.” What do I mean by framing? Framing is a word that can mean many things, and the concept causes considerable confusion, so it is important to proceed with clarity.

In this spirit, yes, a picture frame—like the one that sits around a print on the wall—is indeed a frame. But a picture frame made of wood or metal is not what we are talking about here in the context of a photographic image.

A real-world picture frame is a frame only in the most literal sense, although some art does play with the motif of the external frame, perhaps by incorporating it into the image.

Under the Yaquina Bay Bridge—The Yaquina Bay Bridge is a wonderful and massive Art Deco structure that was built in the 1930s along the Oregon coast.

On a chill autumn morning, exploring around the Yaquina Bay Bridge, I walked through an underpass with my camera and tripod. There I found this marvelous structure, framed through the internal peaked arches.

I do often find myself under things such as bridges. A partial explanation for this propensity is that observing scaffolding, structure, and underpinnings allows one to implement visual framing. I like understanding how things are built and this adds to my sense of the poetry of the place.

In the context of the Yaquina Bay Bridge photo, the image is anchored by the outer frame or border of the image itself. Within this outer frame are a series of receding arches. The most distant arch opens a window on the mechanics that support the cantilevered portion of the bridge.

Photographing through the arches allows a pleasing sense of symmetry and framing that uses the power of the outer border to its best compositional advantage.

Nikon D850, 21mm Zeiss Distagon, six exposures with shutter speeds ranging from 1/125 of a second to 1 second, each exposure at f/22 and ISO 64, tripod mounted.

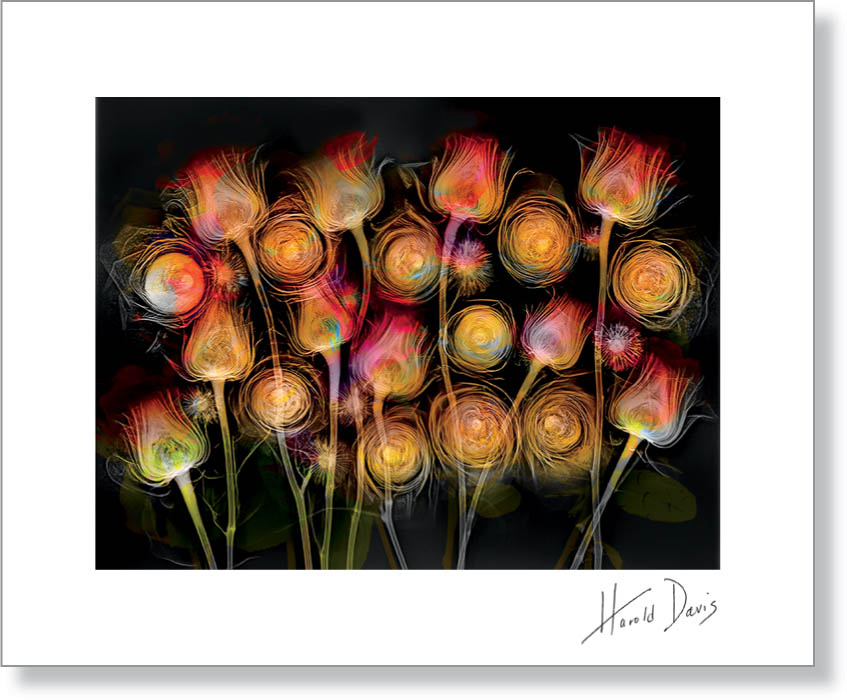

X-Ray Floral Medley Fusion—Working with radiologist and physicist Dr. Julian Köpke, I used an x-ray machine to generate several monochromatic x-ray captures of a composition of roses and ranunculuses. The x-ray machine generated DICOM (medical) files.

I combined the medical files with photography of the same composition on a light box by moving the composition, which had been placed on a sheet of clear plexiglass, from the x-ray machine to the light box. Once it was on the light box, I used my camera and tripod to make a series of captures. All these elements were combined in Photoshop.

The entire image looked quite good framed by a black background and is a popular print of mine. As you can see in the inset below, when I print the image, I leave a white paper border around it as a place to sign the print, and also to create an additional visual border frame and boundary.

Fusion image: DICOM medical x-ray file with light box photo overlay.

The most important part of framing in relationship to photographic composition concerns the boundaries of your image within and surrounding the image itself and does not involve the external picture frame.

All images have compositional boundaries, starting with the perimeter dimensions of the photo. In the case of a print on paper, this compositional boundary is expressed by the edge of the piece of paper, as well as the edges of the photo. In addition, most compositions of any complexity also have a variety of internal borders, boundaries, and frames.

The single most significant frame is that of the image itself. You don’t need to print an image to see this frame. It is perfectly apparent when you look at an image on a monitor or the internet.

One challenge taken on by Composition & Photography is to position photography in relationship to two-dimensional design. Looking at photography from the perspective of two-dimensional design, essentially all photographs must interact in their composition with their own edges.

Let me re-emphasize that the word “frame” can mean a number of different things, including:

- The monitor on which you look at an image.

- The paper border of a print.

- The boundary and edges of the photo itself.

All of these are frames, with the boundaries and edges of the photo being the most universal and useful. Let’s start by looking at how your internal composition can interact well with this photographic frame.

Tondo—In the English Walled Garden area of the Chicago Botanic Garden, a stylized gazebo sports a round porthole to the “outside” world.

I used a rectangular fisheye lens to capture this porthole window in a visual play with the borders of the photo. The circular shape, or tondo, in the center of the image of the image show the kind of bending distortion you would expect from a fisheye lens. This is a reversal of the normal order of things and adds to the interest of the composition.

Nikon D850, 8-15mm Nikkor fisheye at 15mm, five exposures with shutter speeds ranging from 1/13 of a second to 4

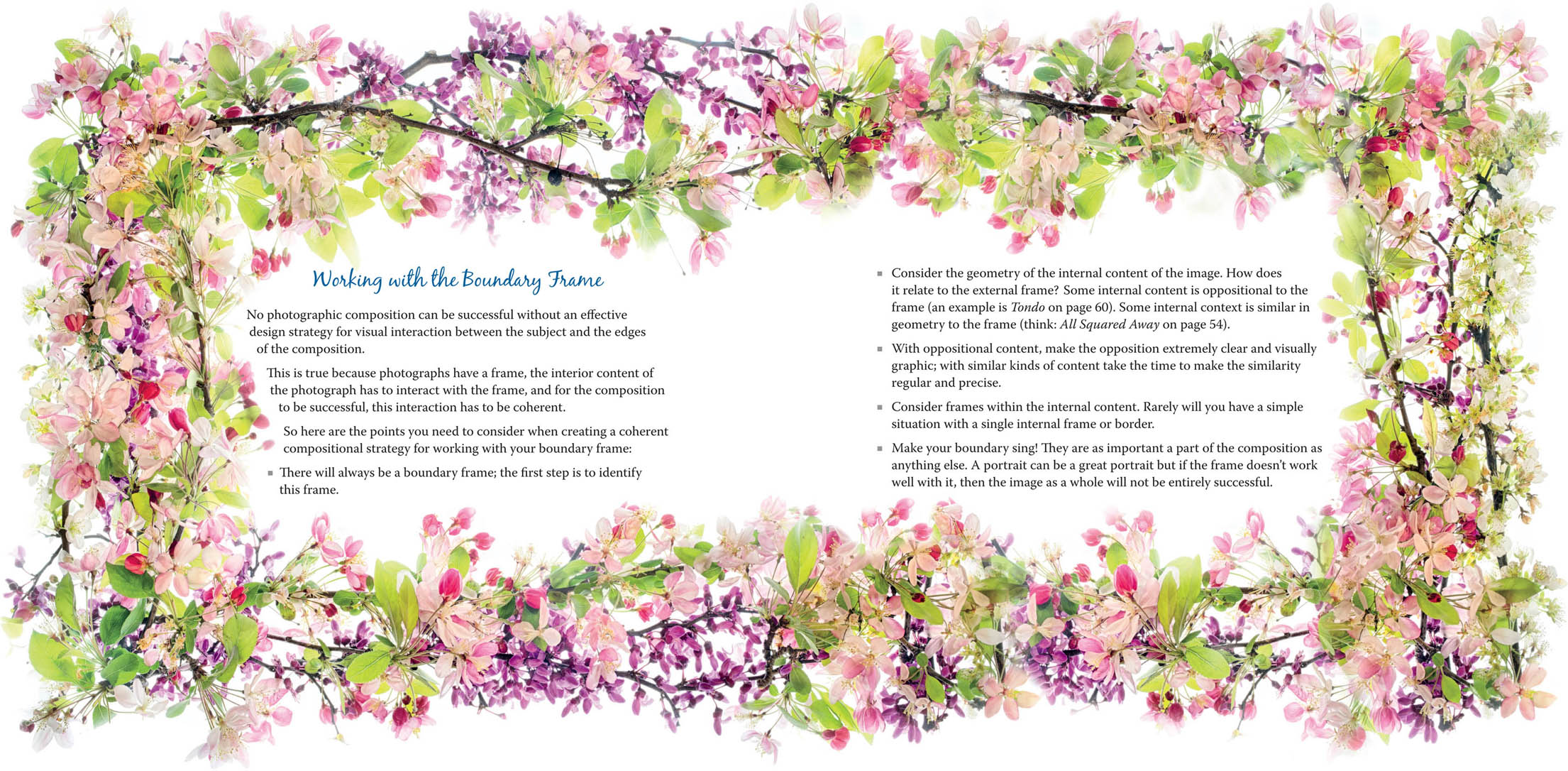

Flowering Branches Frame—It was high springtime near where I live and the branches of flowering trees were magnificent. I brought in a few apple and cherry branches, and I placed them on my light box. My idea was to create a lush floral frame with interior white space. The interior white space could be used eventually to add other design elements, or simply kept as an elegant “picture” frame.

Nikon D850, 55mm Zeiss Otus, seven exposures with shutter speeds ranging from 1/30 of a second to 10 seconds, each exposure at f/16 and ISO 64, tripod mounted.

Metamorphosis—I photographed these beautiful sunflowers, dahlia, and roses—all a little past their prime in the way of wabi-sabi—using an old baking sheet as the background. The title of the image, Metamorphosis, represents the change that comes in life when flowers inevitably fade from their glory. They are beautiful as they age. There will be more flowers. Autumn may tend to winter, but warmth and life will come again in the spring.

When it came time to crop and print Metamorphosis, I noted that the baking sheet acted as an internal frame. With a strong internal frame like this, one does not want to fight the visual dynamics of the image.

It would have been a mistake to use the essentially arbitrary proportions of the digital capture to add another inelegant frame around the baking sheet. So I simply cropped the image closely to the baking sheet’s dimensions. This is slightly off from the original proportions of the capture, but not so much as to be upsetting or alarming, and it creates a visually harmonious image.

Nikon D850, 55mm Zeiss Otus, six exposures with shutter speeds ranging from 1/10 of a second to 6 seconds, each exposure at f/11 and ISO 64, tripod mounted.

Controversy about Proportions

In 1726, Jonathan Swift published his satire Gulliver’s Travels. In this book, the surgeon Lemuel Gulliver traveled to a variety of exotic lands, including Lilliput where the inhabitants were engaged in endless war over which end of an egg was the best to open, the big end or the little end. All this is by way of saying that folks will argue and fight fervently about almost anything.

So it may not surprise you to learn that there is an active and ongoing controversy about cropping proportions of a photograph. “Originalists” maintain that all crops must be in the same proportions as was captured in the camera. On the other hand, hard-core “visualists” just want what serves the image best, and are less concerned about the “authenticity” of any crop.

Well, this is a pretty silly thing to get agitated about. Let me be clear that my sympathies generally fall with the visualists: I want what is best for the image.

However, the originalists do also have a point. If you are someone who views a lot of photographs—as most folk do in our society—or who works with photography, your compositional eye will have become accustomed to certain proportions, such as 1.5:1. Most post-production software specifically allows you to crop in the original proportions. There’s a kind of internal alarm bell that rings when a photograph is presented outside of these original proportions.

You can almost always get away with a square crop, and an original-proportion crop is, of course, expected. But any other crop may tend to make the viewer think consciously or unconsciously that something is awry.

This isn’t to say that you shouldn’t crop out of proportion. Sometimes an unusual crop is fully warranted. What you should know is that an out-of-proportion or non-square crop will often draw a second glance—for better or for worse.

Busting Into and Out of the Frame

So the frame’s the thing. It will be with every photo. But personally, I always get antsy when there are constraints on creative freedom. The frame is a constraint on my creative freedom and I don’t like it one bit!

So what are you going to do when the two-dimensional design constraints take a bite out of your personal creative freedom? You can ignore the situation and go on making great images in a conventional frame. As they say, “where ignorance is bliss, ‘tis folly to be wise.”

That’s fine. But, why be conventional? If you have to have a frame, and you’re feeling antsy, you can either move toward the frame or move away from the frame. “Moving toward the frame” (busting into the frame) means intentionally adding your own frames to photographs in a potentially highly artificial way.

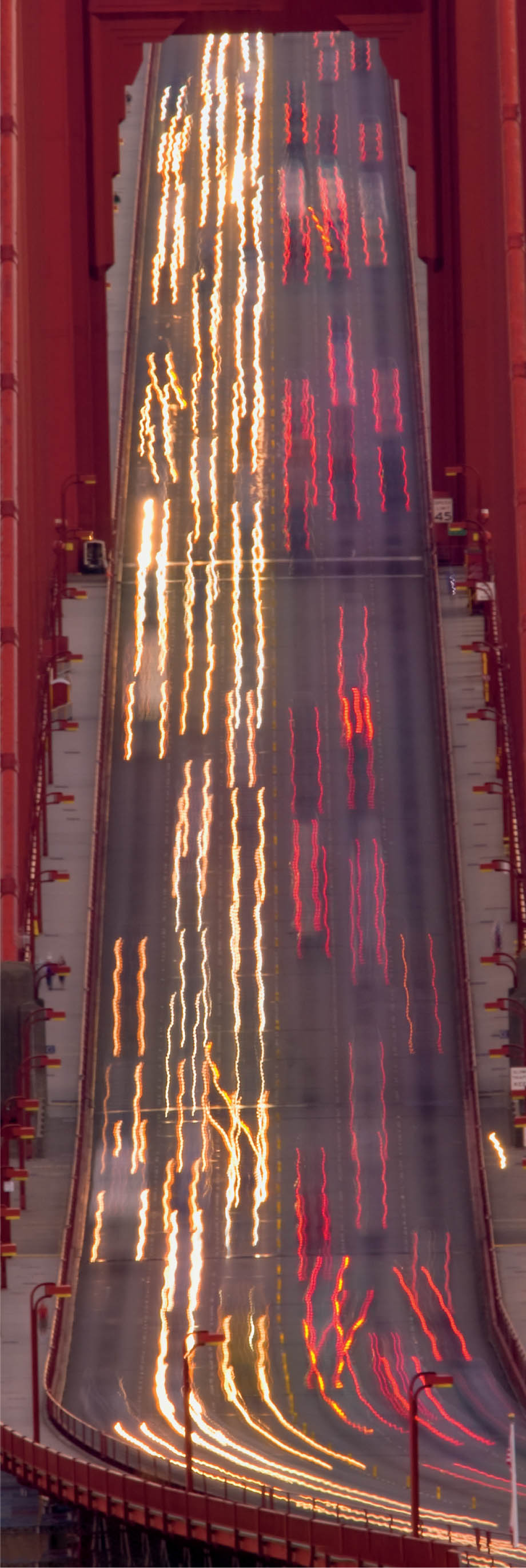

Cars—As late afternoon turned to twilight, I positioned myself on a battlement of the Presidio Battery West in San Francisco. Looking down on the Golden Gate Bridge, I decided to create an image focusing on the traffic on the bridge, so I chose a long telephoto lens (400mm, the equivalent of 600mm in full-frame terms).

With this photograph of traffic, I realized that the important part of the image was the traffic itself. The only way to present this traffic as the essential ingredient of the image was to use an unconventional, thin and long vertical crop.

Nikon D200, 400mm, 3 seconds at f/22 and ISO 100, tripod mounted.

“Busting out of the frame” means placing your image in a context that is not usually thought of as a frame: circles, ovals, spirals, diamonds, having the image ooze out of the rectangle of its frame, adding protrusions to the frame, and so on.

In some cases, such as with journalistic photography, photographers intentionally frame an image so that important parts of the subject are cut off by the frame. This can be used to show busyness, confusion, movement at top speed, or incompleteness. Cutting off a body part or other important element can be a visual indication that something is wrong in the scene. The world is a messy place and using the frame in this way can show it.

There are no rules! Just as what we think of as a “circle” can actually be ovoid or elliptical, a “rectangle” isn’t necessarily a precise and rigid figure with right angles. The concept here is of a generally rectilinear space, but the corners can have some curves, and the lines can have character and be a bit wavy.

Here, we’re not looking for the precision of a geometrician. The key issue when it comes to framing is the relationship of a closed internal space with the outer boundaries of the image. Look for the overall sense and feeling that the shapes and their relationships within the frame convey to the viewer.

Trouble on the Tracks—My inspiration for this collage was the surrealist paintings of René Magritte. In Magritte’s paintings, strange things relating to the framing often happen: snowcapped mountains appear on broken shards of glass; trains tunnel through the sky. So in this image, I used Photoshop to composite an example of a frame within an image showing train tracks that rise through an apparent fold in the landscape; this folds to another portion of the framed image. The idea was to combine apparent plausibility with surreal impossibility.

Landscape: Nikon D810, 28-300mm Nikkor zoom at 150mm, 1/125 of a second at f/8 and ISO 64, tripod mounted; Train tracks: iPhone 6s; images composited in Photoshop.

Dark Angel—When making this image, I asked the model to stand still but move her arms up a step between each exposure. With in-camera multiple exposures, this created a pattern similar to wings. Looking at the image on my studio monitor, it seemed to me that it was closed in and constrained by its visual frame. I decided to go with this effect rather than fighting it, and added a simulated tintype border around the image.

Nikon D850, 50mm Zeiss Otus, in-camera multiple exposure with eight exposures at 1/160 of a second at f/8 and ISO 200, tripod mounted; exposures on a black background using radio-fired strobes; tintype frame added in Photoshop.

Tondos and Circles

An uncommon framing shape that you occasionally see is the circle, or as it is called in the painting world, the tondo.

There are several approaches to creating a tondo photographically. One is to use a circular fisheye lens (like the image of Mosta Dome shown on page 24 and the photo opposite).

Another approach is to construct a round image that is tondo-shaped on a solid background, usually bright white, as in a light box, or black. A third way to create a circular image is to use a selection and mask in Photoshop.

When creating a circular image optically, the name of the game is distortion. Whether you like it or not, your image will show distortion and curvature at the edges. The photo shown on page 60 is a good example of a fisheye—in this case horizontal rather than circular—where the center of the image has almost no distortion, but there is a great deal of bending at the edges.

Effective fisheye images embrace this distortion. They also acknowledge the height and inherent depth of field in an extreme wide-angle lens, and balance this compositionally using near-foreground elements as well as more distant subject matter.

Whether the round image is generated with the lens, as a construction, or in Photoshop, the circularity of a round image calls attention to its framing and to the borders of the image.

This means that compositionally it’s important to create structural bridges between the circular inner image and its frame. For example, the blue flowers at the edges of the tondos shown on pages 72–73 touch the round edges.

This kind of structural bridge serves as a visual path to bring the viewer into the core of the image. Without the connection between the outer and inner portions of a round image, a tondo appears disconnected in space and will struggle to supply emotional meaning.

Crystal Ball—This photograph of a decorative pond at Blake Garden in Kensington, California, reminded me of a crystal ball. I decided to handle the framing issues inherent in a fisheye photograph by adding a black border around the circular area, enhancing the sense that this garden pond is floating in space.

Nikon D850, 8-15mm Nikkor fisheye zoom lens at 8mm, 2 seconds at f/22 and ISO 64, tripod mounted.

Flower Tondo and Flower Tondo Inversion—To create these circular images, I began by making a patterned, circular array of alstroemeria (Peruvian Lily), roses, and agapanthus (Lily of the Nile) on the light box. The main organizing principle was a single rose blossom at the center of the image.

I used a high-key layer stack to capture the composition and then reduced it to the version on white shown on page 72, using a black mask to emphasize the circularity. The inversion on page 73 was created using an LAB L-channel color adjustment.

Nikon D850, 85mm Zeiss Otus, six exposures with shutter speeds ranging from 1/30 of a second to 2 seconds, each exposure at f/13 and ISO 64, tripod mounted.

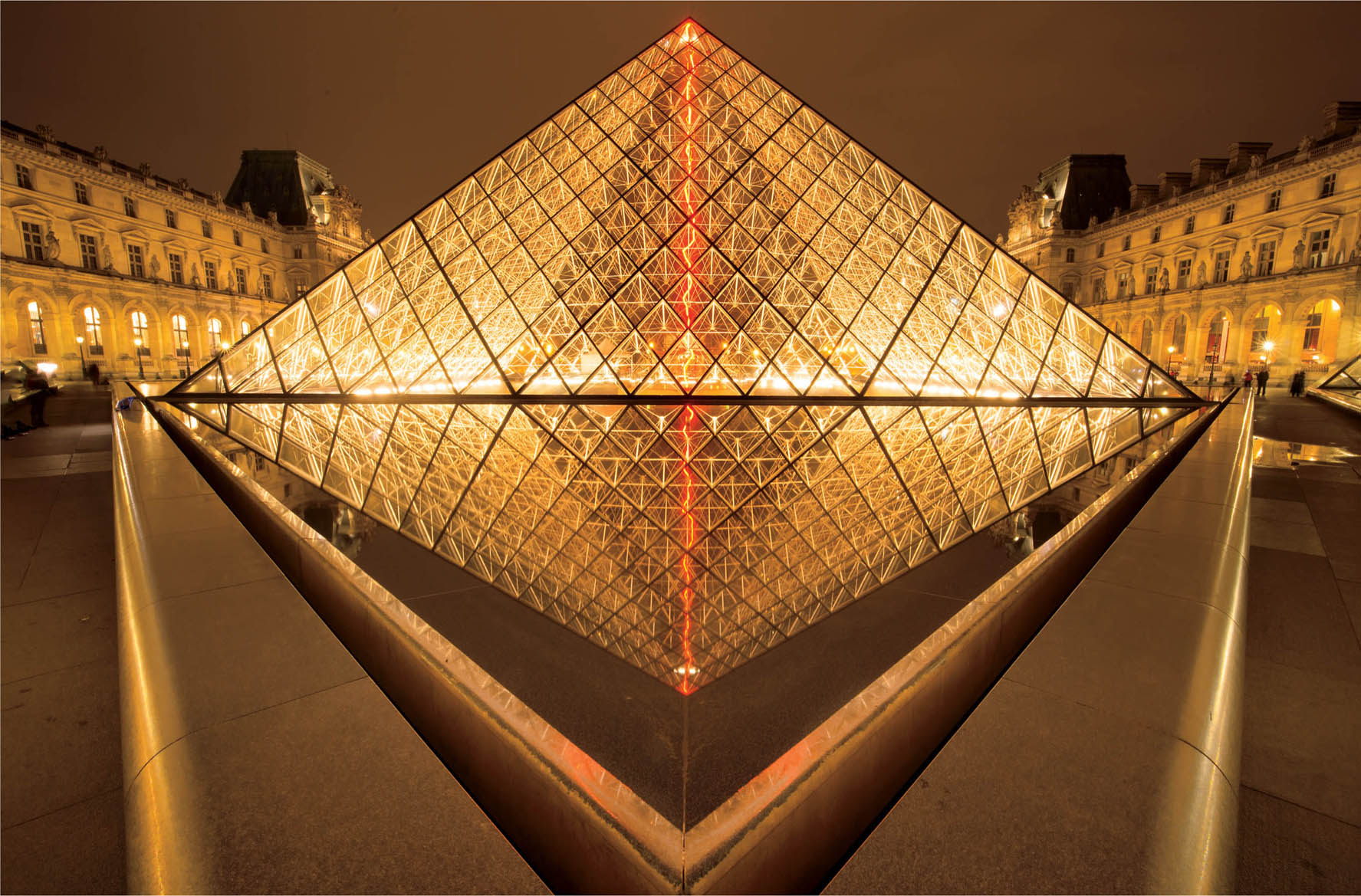

Pyramide—Photographing after dark in the grand courtyard of the Louvre in Paris, France, is great fun! The Pyramide du Louvre, designed by I. M. Pei, becomes an abstraction of triangles and the reflecting pond itself shows triangular shapes.

When making this composition, I used an extreme wide-angle lens (15mm). My idea was to locate the structure of the Pyramide between the earth and sky so that the top of the Pyramide triangle rested against the upper frame of the image and the bottom vertex of the reflected triangle sat toward the bottom of the frame in the pond. The overall visual impact was to create a diamond of lights.

Nikon D800, 15mm Zeiss Distagon, 30 seconds at f/20 and ISO 200, tripod mounted.

Stair Knot—High up in the belfry of an abandoned church in the Cuban city of Trinidad, I laid down on my back and photographed the stairs looking straight up. The resulting image had an almost impossible Escher-like effect with the staircase folding in upon itself. Years after I made the image, I decided to shape the Stair Knot into a triangle. I sent the photo to my iPhone, and used the Fragment app to convert the image into a triangular shape.

Nikon D300, 10.5mm fisheye, 2 seconds at f/22 and ISO 100, tripod mounted; geometric triangular folding added using Fragment on the iPhone.

The Humble but Mighty Triangle

A tripod holds your camera up and the tripod is humble but mighty. From an engineering viewpoint, the tripod and structures made from tripods provide great tensile strength.

But where’s the tripod when it comes to photographic composition?

Pretty much absent except as part of a rectangular composition, and in architectural photography. Maybe we should do something about this—start a trend!

If you want to join the CTU (Club of Triangle Users), consider that a triangle has three sides and three points. Each side and point must relate to and anchor with the surrounding rectangular framing. The only exception to this is when the triangular shape itself has been cut out, as in the image shown on this page.

Let’s emphasize: explicit triangles are fairly rare in compositions. Triangles can be powerful in photos and convey a sense of muscular compositional strength. Within a rectangular framing, triangles need to be clearly anchored at their vertices to the framework of the photo.

Working with Internal Rectangles

An image with internal rectangles is essentially presenting a frame within a frame. This may sound simple, but there is actually no end to the possibilities and complications of internal framing created with rectangles inside an image.

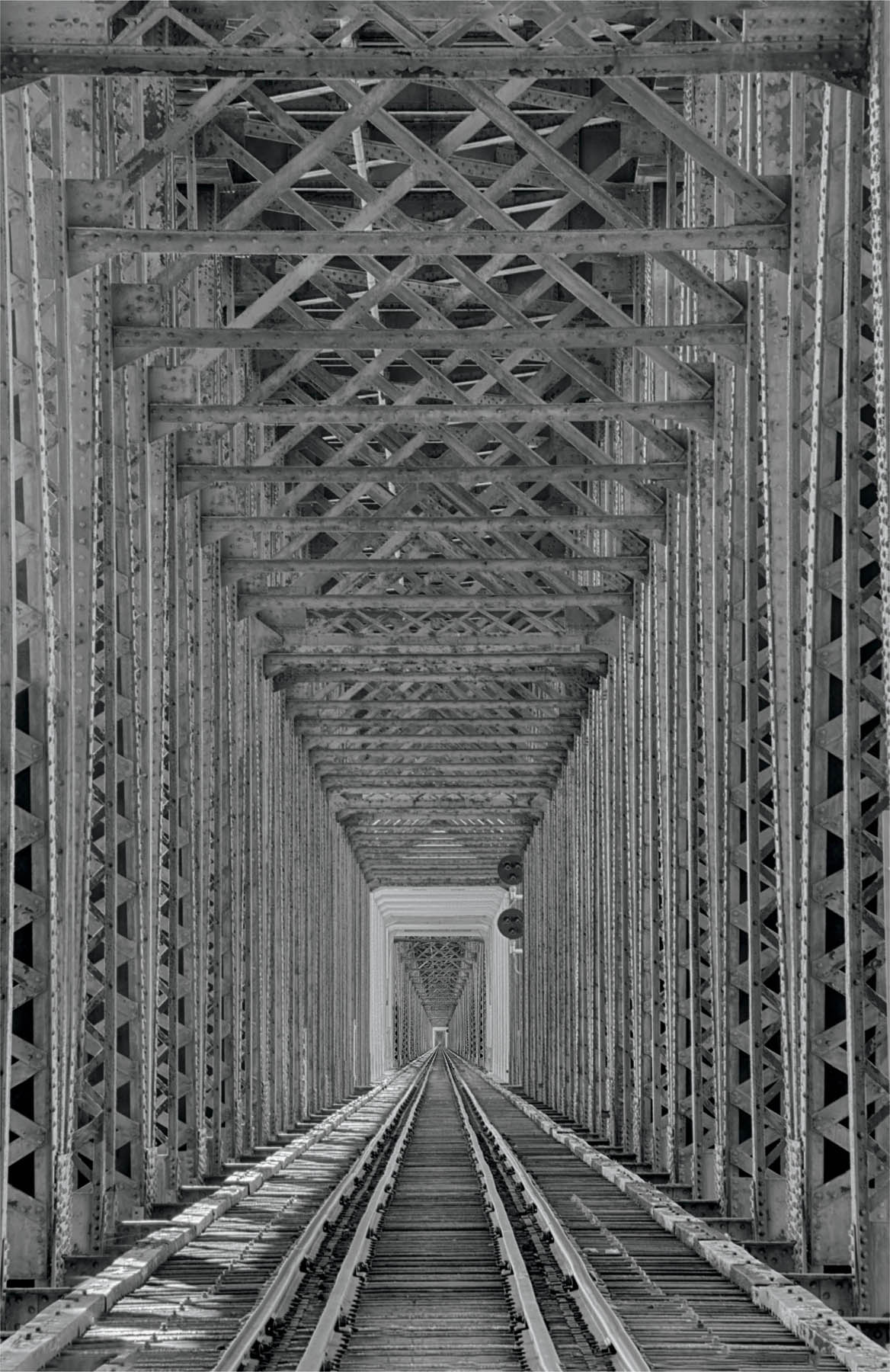

When the internal frames in an image are one after the other in a receding progression—as in Endless Doors on page 15 or Train Bridge, Maine shown opposite—this creates a unique sense of order as well as a visual approach to the infinite. For more about patterns and progressions, see pages 82–107.

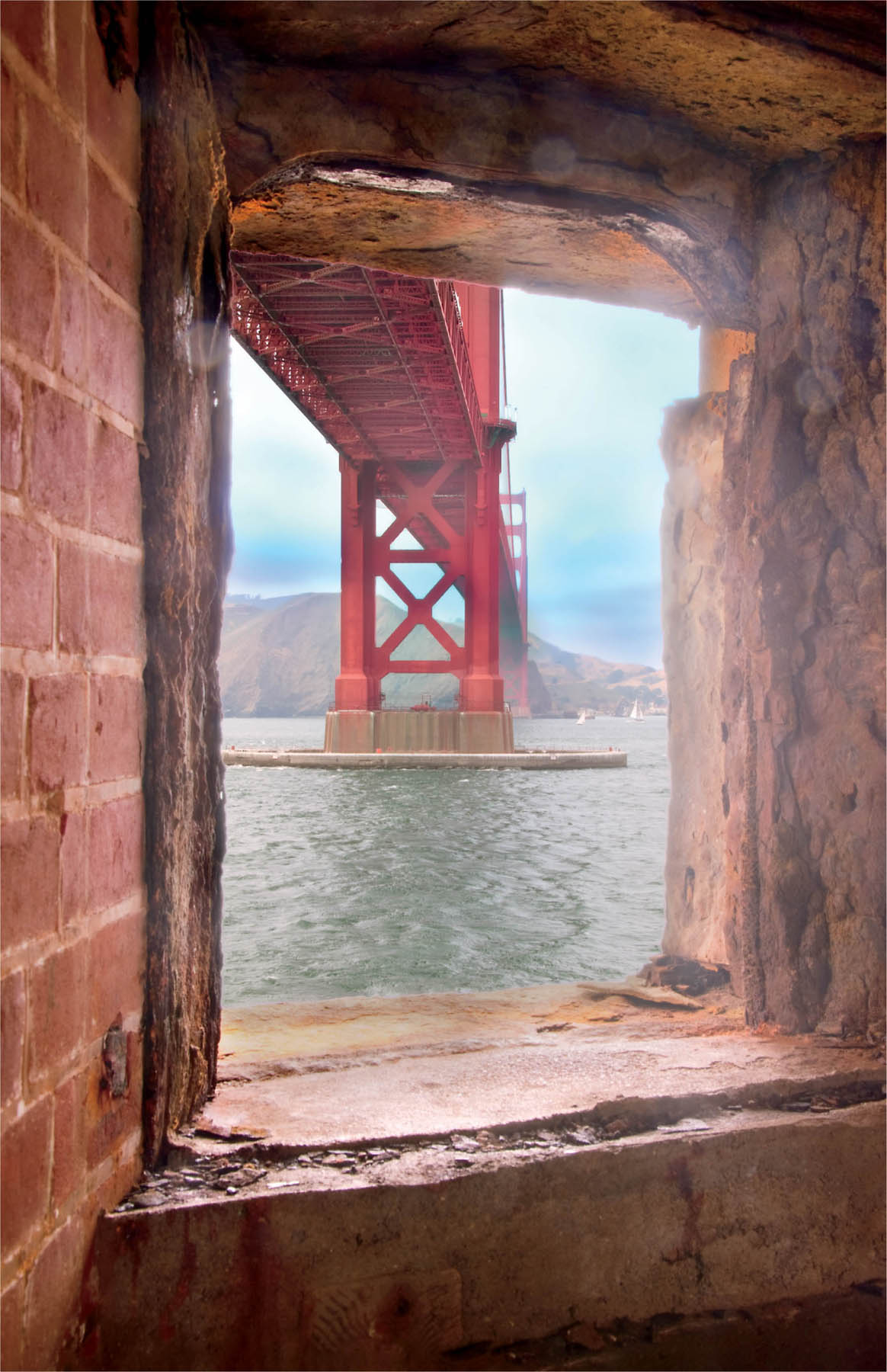

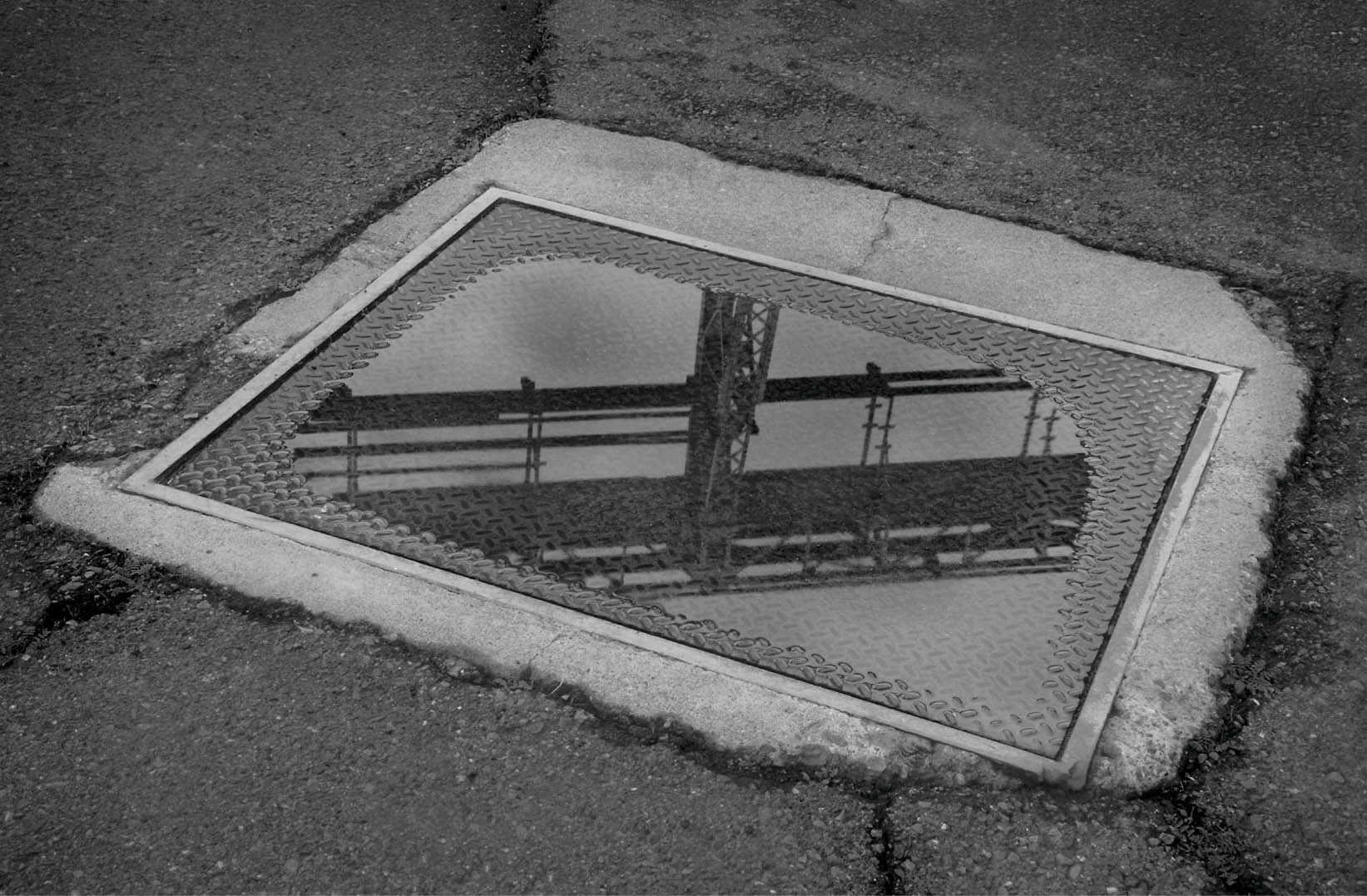

Alternatively, an internal frame can represent a simple shape such as a window or a door, as shown in Golden Gate Window on page 78, or even a reflection in a puddle, as in Framed on page 79.

As you can see, one of the most common and effective motifs in photographic composition is the frame-within-a-frame, whether the inner frame is a literal window, a door, a reflection in a puddle, or sticks in a forest on the edge of a marsh.

The point is that internal framing creates a connection between the viewers’ world outside the image and the more subjective material within the image. Yes, a frame bounds the image, but it is also a frame of regard and connotes passages and transitions.

When you are working with internal rectangles and frames-within-frames, pay special attention to the relationship of these internal frames to the external frame of the image. Your viewers will be scrutinizing this relationship whether they consciously know it or not.

Regularity—or irregularity—matters. A composition where the inner rectangles are lined up in an orderly way presents a very different world view from a composition where the rectangles seem askew or at an angle. In the first case, you have a progression that doesn’t seem to end and represents a reasoned universe. In the second, you have something quirky, unusual, and potentially interesting.

I suggest that you consider the role of internal rectangles and frames-within-frames in any image where you are paying attention to the composition.

Train Bridge, Maine—Exploring the old ship-building town of Bath, Maine, I was surprised to find this almost abandoned train bridge crossing the Kennebec River. Climbing onto the trestle, I hoped not to encounter one of the remaining trains. In the meantime, I could see through my lens an alternating pattern of light and dark rectangles, receding to the infinite vanishing point.

It is interesting that from a compositional point of view, I was not really concerned with the engineering of steel girders when I made this image. The relationship of the internal frames and how they work together is what inspired the image, rather than the idea of a train bridge.

Nikon D810, 28-300mm Nikkor zoom at 250mm, eight exposures with shutter speeds ranging from 1/250 of a second to 1 second, each exposure at f/22 and ISO 64, tripod mounted.

Golden Gate Window—Fort Point, in the shadow of the Golden Gate Bridge, has guarded California since the 1860s. Wandering around the lower levels, I spied this open window with a view out toward the bridge. It seemed to me that the real compositional story was the relationship of the dusty, stone window frame to the view of the bridge and landscape beyond, and the way the window related to the outer image frame.

Nikon D300, 18-200mm Nikkor zoom at 29mm, two exposures with shutter speeds of 1/20 of a second and 1 second, each exposure at f/22 and ISO 100, tripod mounted.

Framed—During World War II, Mare Island was the largest naval shipyard on the Pacific Coast. Today, it is an area of abandoned cranes, gantries, and dry docks. Exploring Mare Island with my camera, I came across this reflection in a puddle.

I created this simple-looking and interesting composition by positioning the puddle so that the internal frame was at an almost forty-five degree angle to the outer frame, with the reflection horizontally bisecting the image.

Nikon D300, 18-200mm Nikkor zoom at 36mm, 1 second at f/29 and ISO 100, tripod mounted.

A Process of Framing

I’m excited by borders, frames, and boundaries! After all, the real magic happens when one slips from one domain to another—often in shadows, elusively, without being aware of the frame.

By slightly altering a frame, giving it a twist or a tweak, one can change the perception of the viewer and enter the realm of visual sorcery.

At the same time, there is certainly no formula for placing a frame within a frame. Once again, the only rule is that there are no rules. So what I am preaching is mindfulness:

- All images have an outer frame.

- Most images have an inner frame or frames.

- The relationship between the frames in an image, and particularly the inner and outer frames, is very important.

- Sometimes images with internal frames that appear simple are actually quite visually complex. This complexity is often “under the covers.”

- Where does one frame end and another frame begin?

- Can you tell the subject matter that is framed from the content that is doing the framing?

Frames provide the underlying structure for much of creative photography and its compositions. Without the basic frame, there is no content. Without internal frames, there is no dialog between the interior composition and the external world of the frame. So pay particular attention to the questions involving boundaries and borders when you work through the process of framing in your images.

Door, Trapani—Wandering the dusty and decaying Sicilian seaport of Trapani, I enjoyed photographing the ancient architecture of this old city. Along the central avenue, Via Garibaldi, I came across this ornate door with the internal door open to the garden in the courtyard. In the context of a photographic frame, you have the oval door, and within that an inner frame.

Nikon D850, 28-300 Nikkor zoom at 50mm, nine exposures with shutter speeds ranging from 1/15 of a second to 8 seconds, each exposure at f/22 and ISO 64, tripod mounted.