The suggestion that options are easy paths to riches does not work for conservative portfolio management. As a conservative investor, you want to know exactly how options might or might not work in your portfolio, and also you want the information to be presented clearly and logically. Since this involves a narrow range of possible strategies—only those appropriate in a conservative portfolio—much of the exotic but high-risk potential of options is avoided.

Even the most experienced investor struggles with terminology and the meaning of key concepts, so this chapter covers the important options basics, including explanations of calls and puts in either long or short positions; how option contracts work; expiration of options; strike prices; and time, extrinsic, and intrinsic values. In discussing the range of possible strategies, the purpose is not to recommend any approach but to explore and review all the possibilities.

The Workings of the Options Contract

The mechanics of expiration, strike price, and time, extrinsic, and intrinsic values affect all decisions related to how you should or should not employ options and how risks increase or decrease as you act to create a strategy.

Option Attributes to Determine Value

Collectively, the attributes of the option contract determine its value. Option contracts refer to 100 shares of stock, meaning that each option contract allows the buyer to control 100 shares of the underlying stock. Every option relates specifically to that one stock and cannot be transferred. The premium is the cost (to the buyer) or value (to the seller) of the option. This cost/value is expressed as the value per share, without dollar signs. For example, if an option’s current premium is listed as 6, it is worth $600, and if the current premium is listed as 4.75, it is worth $475. Premium is expressed as a single number for round values (like 6) or with two decimals for all others (such as 4.75 or 4.50).

Expiration occurs for all options. The potential profit period for the option speculator is the flip side of the advantage the short seller enjoys. Just as a short seller of stock sells and has an open position, the short seller sells the option. The short option position can be closed in one of three ways. First, it may expire worthless, in which case the entire premium received by the seller is profit. Second, it may be closed by buying to close at any time, with the difference between the initial sales price and final purchase price representing profit or loss. Third, it may be exercised by the buyer, and the short seller will then be obligated to complete the exercise transaction. When a call is exercised, the seller is required to deliver 100 shares of stock at the strike price. When a put is exercised, the seller is required to take delivery of 100 shares at the strike price. Shares are “assigned” (put to the seller).

Intrinsic, Extrinsic, and Time Values Premium

An option premium has three components: intrinsic value, extrinsic value, and time value. The intrinsic value is equal to the number of points that an option is in the money (ITM). This concept is explained in greater detail later in this chapter. The strike is the price at which an option can be exercised; for example, if a call option has a strike price of 45, it provides the buyer the right (but not the requirement) to buy 100 shares at $45 per share. The money rules, or “moneyness,” for this example are as follows.

- If a 45 call is held on stock currently valued at $47 per share, the option is 2 points ITM.

- If the stock is valued at $45 per share, there is no intrinsic value. This condition—when strike price and stock market value are identical—is called at the money (ATM).

- If the stock is valued below the strike price, there is no intrinsic value. For example, if the strike price is 45 and the stock is selling at $44 per share, the condition is 1 point out of the money (OTM).

The opposite direction applies to puts. ITM intrinsic value refers to the number of points the stock is below the strike price of the option. For example, if the strike price of a put is 40 and the stock is currently selling at $37 per share, the put option contains 3 points of intrinsic value.

Time value and extrinsic value are the portions of the option premium above and beyond intrinsic value. The longer the time to expiration date, the higher the time value. This value decays over time in a predictable manner, accelerating as expiration nears.

Extrinsic value is the key to identifying option opportunities; it is the volatility premium of the options beyond both intrinsic and time values premium, also called implied volatility.

Long-Term Options and Their Advantages

The LEAPS (Long-term Equity AnticiPation Security) is a long-term contract. In comparison, the standard listed option lasts only about nine months maximum. When various strategies are viewed comparing LEAPS options with listed options, that longer expiration makes a lot of difference to both long and short strategies. There is a far higher time value in a long-term LEAPS option, which exists for up to 30 months. If you purchase options, you must expect to pay more for the longer life of the LEAPS option, because you also buy greater time. For the short seller, the longer period translates to higher income; because as a seller, you receive the premium when you open the short position. For that higher premium income, you must also accept a longer exposure period.

The expiration, more specifically, the time between opening an option position and the expiration date determines the extrinsic value and affects the decisions made on the long side (purchasers) and the short side (sellers).

Strike Price of Options

The strike price is the second feature that determines the option’s value. The strike price is fixed and, in the event of exercise, determines the cost or benefit to every option position, whether long or short. The proximity of current market value to the strike price of the option also determines the current premium value and the potential for future gain or loss, as well as the likelihood of exercise. For example, if a call’s strike price is 30 (meaning it would be exercised at $30 per share) and the current market value of the stock is $34, the call is 4 points ITM. This option will be exercised in this condition. If the stock’s price declines to $28 per share, the call would be 2 points OTM; and if the price stops at the strike price of $30 per share, it is ATM. These conditions are opposite for puts.

Extrinsic value premium is the intangible portion of the premium value. Extrinsic value varies depending on the volatility of the underlying stock.

The Time Advantage for Short Sellers

For the option seller, time is an advantage. The higher the time value premium when the short position is opened, the greater the advantage. If you were to sell a call with 7 points of time value, you could buy to close the position at a profit if the premium value was lower than the original 7 points. For example, if the stock was 5 points higher than the strike price near expiration, you could close the position and avoid exercise—and make a $200 profit ($700 received when the short position was opened, minus $500 paid to close the position—not considering trading fees).

The intrinsic value of the option premium is equal to the number of points and the option is ITM. For example, if your 40 option is held on stock currently valued at $43 per share, the option contains 3 points of intrinsic value. If that call is currently valued at 5 ($500), it consists of $300 intrinsic value and $200 time and extrinsic values. If your put has a strike price of 30 and the stock is valued at 29, the put has 1 point—$100—of intrinsic value because the stock’s value is 1 point below the put’s strike price. If the current value of the put is 4 ($400), it consists of $100 intrinsic value and $300 time and extrinsic values.

Long and Short

The decision to go long (buy options) or short (sell options) involves analyzing opposite sides of the risk spectrum. Strategies cover the entire range of risk, often only with a subtle change. Long options are disadvantageous in the sense that time works against the buyer; time value disappears as expiration approaches. The less time until expiration, the more difficult it is to profit from buying options; and the longer the time until expiration, the more the speculator must pay to buy contracts. Long options can insure paper profits, but the more popular application of long options is to leverage capital and speculate.

Options present occasional opportunities to take advantage of price swings. When overall market prices fall suddenly, conventional wisdom identifies the occurrence as a buying opportunity; realistically, such price movements make investors fearful, and it is unlikely that many people will willingly place more capital at risk—especially because the paper position of the portfolio is at a loss. Buying options can represent a limited risk for potentially rewarding profits—an opportunity to buy more shares of stock you think of as a long-term hold.

Taking Profits Without Selling Stock

The same argument applies when stock prices rise quickly. Sudden price run-ups are of concern to you as a long-term conservative investor. The dilemma is that you do not want to sell shares and take profits because you want to hold the stock as a long-term investment; at the same time, you expect a price correction. In this situation, you can use long puts to offset price decline.

If you want to hold stock for the long term, you may be willing to ignore short-term price volatility. Even so, few investors can ignore dramatic price movement in their portfolio. When prices plummet or soar, the change in price levels may be only temporary. The tendency for some investors is to sell at the low or to buy at a price peak. In other words, rather than following the wisdom “buy low, sell high,” investors often react to short-term trends and “buy high, sell low.” You can use options to exploit the market roller coaster. Options can help you deal with price volatility on the upside or the downside for fairly low risk and without losing sight of your long-term investment goals.

The question of speculative versus conservative is not easily addressed. Using options to play market prices is speculative; but at times, you can take advantage of that volatility without selling off shares from your portfolio. The same observation applies on the short side of options, where risks are far different and market strategies vary.

Buyer and Seller Positions Compared

When you short options, you do not have the rights that buyers enjoy. Buyers pay for the right to decide whether to exercise or to sell their long positions. When you are short, you receive payment when you open the position, but someone else decides whether to exercise. Time value works to your advantage in the short position, meaning you control risks while creating a short-term income stream.

The highest risk use of options is the uncovered call. When you sell a call, you receive a premium, but you also accept a potentially unlimited risk. If the stock’s market value rises many points and the call is exercised, you will have to pay the difference between the strike price and current market value at the time of exercise. In comparison, the covered call is one of the lowest risk strategies. If you own 100 shares, you can deliver those shares to satisfy exercise, no matter what the market price is. Upon exercise, you keep the premium you were paid.

The capital gain created when a covered call is exercised may produce impressive levels of profit if the basis in stock was lower than the call’s strike. In addition, you earn dividends if you continue to own stock.

Understanding Short Seller Risks

The decision to employ options in either long or short positions defines risk profile; the definition of conservative is rarely fixed or inflexible. It is more likely to define an overall level of attitude about specific strategies while acknowledging that strategies may be appropriate in different circumstances. It is a matter of timing a decision based on the current status of the market, your portfolio, and your personal decision to act or to wait out volatile market conditions.

Calls and Call Strategies

If you buy a call or a put option, you have the right to take certain actions in the future, but you do not have an obligation. If you sell a call or a put, the premium you receive as part of an opening transaction is yours to keep, whether the option is later closed, expires, or is exercised.

Options are contracts that grant specific rights to the buyer and impose specific obligations on the seller. If you think of options as intangible contractual, the discussion of how to use options is easier. For example, in a real estate lease option, you have two parts: a lease specifying monthly rent and other terms, and an option. The option fixes the price of the property. If you decide to exercise that option before it expires, you can buy the property at the specified contractual price even if property values are significantly higher.

Stock market options are the same, but they involve options on stock instead of real estate. Every option refers to 100 shares of stock, and options come in two types: calls and puts. When you buy a call, you acquire the right to buy 100 shares of stock at a specific price (the strike price) before the option expires. All options have fixed expiration dates, so the time element of options is a crucial feature to consider when comparing option values. For the buyer, a relatively small risk of capital potentially fixes the price of 100 shares of stock for several months. If that buyer decides to buy the stock, the call can be exercised to acquire 100 shares at a price below current market value. That is the essence of the call.

Is the Strategy Appropriate?

Buying calls is not an appropriate fit in most applications. Buying calls is the best known and most popular option strategy, but it is usually a purely speculative move. If you are convinced that a stock’s market value is sure to rise before the expiration of an option, you can buy calls as an alternative to outright purchase of shares. This strategy would be appropriate in the following circumstances.

- You are concerned with short-term price volatility, and you do not want to commit funds to buy shares, but you still want to fix the price of stock at the option’s strike price value.

- You want to buy shares, but you do not have funds available now, so buying a relatively cheap call is a sensible alternative (given the chance that you could lose the money).

- You are aware of the risk of loss, and you want to proceed with buying a call anyway, hoping for profits when the price rises.

As with any general rule, there are exceptions. You retain your status as a conservative investor even though circumstances may arise where you want to buy a call. It is not a conservative strategy, but all investment decisions should be driven by circumstances and not by hard-and-fast rules. Although the general rules you set for yourself guide your portfolio decisions, special circumstances and opportunities or limitations can cause exceptions.

Option Terms and Their Meaning

Every call contains a series of terms. These are the type of option, the strike price, the underlying stock, and the expiration date.

The type of option is either a call or a put. The two must be distinguished because they are opposites. All the terms must be specified in an order, including whether you want a call or a put.

The strike price is the price of stock that may be acquired if the option is exercised. This strike price remains unchanged until the option expires, except in cases of stock splits. You have the choice as a buyer of either selling the option to close the position or exercising the option. Upon exercise of a call, you buy shares at the strike price. You “call away” the 100 shares of stock from the call seller. If you exercise a put, you have the right to sell 100 shares, or to “put shares of stock” to the seller and dispose of stock at the fixed strike price.

The underlying stock is the security on which the option is traded. The security cannot be changed; it is fixed. Options are not available on all stocks, but they can be found for most stocks listed on the stock exchanges.

The expiration date is a fixed date in the future specifying when the option expires. This term is critical because after the expiration date, the option no longer exists. As a buyer, you know that the time value premium evaporates if your option is not exercised or sold before the expiration date.

These four terms collectively distinguish every option. None of the terms can be modified or exchanged after you open an option, and the terms determine the option’s value (the premium you pay when you open the option).

The Cost of Trading

Augmenting the complexity of buying is the trading expense involved. This applies to both sides of the transaction. You are charged a fee when you open the position and another fee when you close it. In any calculation of risk and potential profit or loss, the cost of trading must be included. If you deal with single-option contracts, you limit your exposure to loss. But at the same time, the per-option cost of trading is higher. Option traders often execute transactions using multiple option contracts. This reduces the per-option cost. But buying options is a high-risk venture and using multiple contracts just to reduce per-option trading costs does not reduce overall risk; it increases the risk, because you must put more capital at risk. For the option buyer, trading costs make the proposition even less likely to turn out profitably. The typical trading fee will be about $5 for trading a single option. Entering and then exiting a trade costs about $10.

As a call buyer, the odds are against you. A second possibility is far more interesting and potentially more profitable: selling calls. Selling stock involves the sequence of events that is opposite from when you go long. You must borrow shares of stock to sell, and opening the short position exposes you to the possibility of loss. If the stock’s market value rises, you lose money. Short sellers expect the price of stock to fall. Eventually, they close the position by entering a closing purchase transaction. Short sellers must make enough profit to offset the cost of borrowing stock, trading fees, and the point spread between original selling price and final purchase price.

Selling stock is high risk. If the stock’s value rises, you lose money, and short sellers are continually exposed to that market risk. In comparison, using short options is a less expensive alternative to shorting stock.

In, At, or Out of the Money

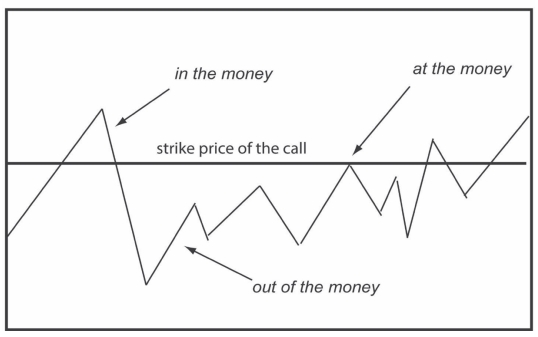

Selling a call is easier than selling short shares of stock, because you do not have to borrow calls to go short. You simply enter a sell order, and the premium (the value of the call) is placed into your account the following day. When you sell a call in this manner, you are in the same market posture as the short seller of stock, but at less risk. You are hoping that the price of stock will fall so that your short call will lose value. This means you will be able to either close the position profitably with a closing purchase transaction or wait for the call to expire worthless. If the market value of the underlying stock remains at the strike price (ATM) or below the strike price of the call (OTM), exercise will not occur. When the stock’s market value is higher than the call’s strike price (ITM), you are at risk of exercise. The proximity of the stock’s current market value to the strike price is summarized in Figure 2.1.

The option’s strike price remains level, but the status of the option relies on stock price movement. This illustrates how a call functions. Whenever the stock’s price is higher than the call’s strike price, the call is ITM, and whenever the stock’s price is below strike price, the call is OTM.

The same logic applies to a put, but the terms are reversed. Referring again to Figure 2.1, if the stock’s price was higher than the strike price of the put, it would be OTM, and if the stock’s price moved below the strike price, the put would be ITM.

Figure 2.1 Strike price and stock price

The relationship between strike price and stock price is critical in opening a short position in options. The short-call position can be one of the highest risk positions. However, it can also be one of the most conservative positions. This riddle is explained by whether you own 100 shares of stock when you sell a call. If you go short with calls and you do not own the stock, risks are theoretically unlimited because the market value of stock can rise indefinitely. This uncovered call strategy is inappropriate for your conservative portfolio. However, when you own 100 shares, those shares are available in the event the call is exercised; in the right circumstances, call selling is highly profitable and conservative. Chapter 3, “Options in Context,” compares short calls in these contradictory risk profiles and Chapter 6, “Options as Cash Generators,” provide in-depth explanations of covered call-writing strategies, the ultimate conservative use of options.

Puts and Put Strategies

The put is the opposite of the call. If you buy a put, you acquire the right (but not the obligation) to sell 100 shares of the underlying stock. If you exercise a put, you sell 100 shares at that strike price, even if the current market value of stock is far below that level. Like the call, the put expires at a specific date in the future.

As a put buyer, three outcomes are possible.

- The put is sold. You can sell the put at any time prior to expiration. Since time value declines over the holding period, it is a highly speculative strategy to buy puts purely for short-term profits. If you believe that stocks in your portfolio are overbought and you want to protect paper profits, long puts can be used as a form of insurance to protect your stock positions.

- The put expires worthless. If you take no action before the expiration date, the long put becomes worthless, and the entire premium you paid would be a loss. When you buy puts, you profit only if the market value of the underlying stock declines; if the value remains at or above the strike price, your put does not appreciate.

- You exercise the put. If the stock’s current market value is far lower than the put’s strike price, you have the right to sell 100 shares at the higher strike price. If you own shares of stock and you bought the put for downside protection, exercise can work as a sensible exit strategy.

The Overlooked Value of Puts

The put’s strategic potential is easily overlooked by investors and speculators. More attention is paid to calls. There are good reasons for this. Short calls can be covered by ownership of 100 shares of stock per call but puts cannot be covered in the same way. The put is more exotic and alien to the mindset of many investors.

Where do puts fit for the conservative investor? Several possible applications of puts are worth considering on both the long and short sides. The best known is the use of long puts for insurance. If you buy one put for every 100 shares of stock, you protect your paper profits; in the event of a decline in the stock’s market value, the put’s premium value increases. Once the stock’s price goes below the put’s strike price, loss of stock value is replaced dollar for dollar in higher put premium value.

This protection of paper profits—a form of insurance—is a conservative strategy. You pay a premium for the put because you fear that stock prices have risen too quickly, but you do not want to take profits in the stock. You can use puts in this situation to keep the stock while protecting profits. This insurance does not have to be expensive. Just as you can select insurance based on varying levels of deductible and copayment dollar values, you can select puts based on their cost and level of protection. You could buy puts at lower strike prices; these would be far cheaper but would provide less protection.

Conservative Guidelines: Selling Puts

Is selling puts a conservative strategy? You must assume several elements to conclude that short puts are appropriate in your conservative portfolio:

- The strike price is a fair price for the stock. Whenever you short a put, you must accept the possibility that the put will be exercised. You must accept the strike price as a price you are willing to pay for the stock.

- The premium you receive justifies the exposure. When you sell options, you are paid the premium. That premium and the length of time you remain exposed to possible exercise must justify the decision.

- The risk range is minimal. When you consider the spread between the put’s strike price and your estimated support price for the stock, minus the put premium, how many points remain?

The uncovered put has the same market risk as the covered call, making short puts conservative and in many cases, preferable to covered calls, because you do not need to own the underlying stock to write short puts.

Listed Options and LEAPS Options

Traditionally, risk assessment for options is based on a short lifespan—eight months or less for listed options. The ever-growing popularity of LEAPS—long-term options that last if 30 months—changes the analysis. Even for the long position, the risk of ever-declining time value takes on a different context when looking two or two and half years ahead.

The availability of long-term options makes long positions more viable in many more situations. Longer-term options contain far greater time value, of course, because time value is just that the value of time. So, compared with a six- or eight-month time span, a 24- to 30-month option has far greater potential—for both long and short positions.

Using Long Calls in Volatile Markets

The not-uncommon situation of a volatile market makes it difficult even for conservative investors to time their decisions. It could make sense to buy LEAPS calls instead of stock. As an initial risk analysis, you cannot lose more than the premium cost of the LEAPS call, so the initial market risk is lower. At the same time, in going long with calls, you acquire the right (but not the obligation) to buy 100 shares of the underlying stock at any time before expiration. If the LEAPS call has 30 months to go, a lot can happen between now and then.

The risk is that the stock’s market value will not rise, or even if it does, it may not rise enough to offset the cost of time value and to appreciate adequately to justify your investment. The solution allows you to reduce the cost of buying the LEAPS call by selling calls on the same stock. If the short calls expire before the long LEAPS call, and if the short call’s strike prices are higher than the strike price of the long call, there is no market risk. A likely scenario in this “covered option” position is that the short call’s time value will decline; it can be closed at a profit and replaced with another short call. It is possible, based on ideal price movement of the underlying stock, that your premium income from selling short calls can repay the entire cost of the long-term long LEAPS position. There are no guarantees, but it is possible.

The basic long–short LEAPS strategy is summarized in Figure 2.2.

.jpg)

Figure 2.2 Long- and short-call strategy

This strategy has two legs. First, you purchase a long call with a 50 strike price, and later, you sell a 55 call. To avoid an uncovered short position, the 55 call must expire at the same time as the long call, or before. If the short call outlasts the long call, you face a period in which that short call will be uncovered.

Using LEAPS Puts in a Covered Capacity

Long LEAPS puts can also be part of a two-step strategy. For example, you purchase LEAPS puts for insurance on existing long stock positions and reduce your insurance cost by selling puts that expire sooner than the LEAPS put and have lower strike prices. This basic strategy—

combining long puts and covering them with short puts—is summarized in Figure 2.3.

.jpg)

Figure 2.3 Long- and short-put strategy

The purpose in covering the put is to reduce the risk of exercise and resulting loss, and at the same time, to reduce the cost of buying the long put. These strategies—covering long options with shorter-term short positions—work best when your estimate of likely price movement in the stock is correct. The wisdom of using either strategy is based on your ability to read intermediate-term volatility trends accurately. The strategies make long positions in options more practical than the purely speculative approach, but profitability is not ensured. The overall purpose of the long option strategy is to maximize the opportunity while identifying worst-case outcomes and setting up the strategies so that you will not lose or so that losses are minimal.

Limiting Your Strategies to Conservative Plays

The basic premise for conservative options trading is: Any strategy should be used only on stocks with sound fundamentals that you bought for their value, not used simply to write options with high volatility. The existence of strong fundamental value in the stock, long-term growth, dividend income, and repetitive options trades maximizes the conservative strategy.

Risk levels of the underlying stock may increase since original purchase date, possibly a signal that the underlying should be reevaluated. Should you sell that stock and find an alternative issue with lower volatility levels? You may be better off respecting your conservative stock standards based on fundamental analysis, writing options with “typical” pricing, and staying away from stocks and options with higher than average volatility.

The idea of avoiding stocks and options with higher than average implied that volatility makes sense in your conservative portfolio. If you restrict your activity to long stock positions, you monitor your portfolio constantly. If the fundamentals change, you replace your hold position with a sell. Not only should that standard be retained, but the implied volatility in option premium can serve as a red flag, enabling you to check other indicators to decide whether you want to keep your long stock position.

Identifying Quality of Earnings

The last word in picking options is that quality of earnings mandates the quantifications of a stock.1 The fundamentals apply only to the stock because options have no tangible value. When the option’s implied volatility changes from the norm, it happens for a reason. It is a symptom and perhaps a signal that the fundamental strength (the quality of earnings) of the stock has changed as well. Anticipation is the spark of the stock market, and more decisions are made in anticipation of future risk, profit, and other change than on any known fundamentals. In adhering to your conservative standards, a highly volatile option premium may be a more cautionary sign than a covered call opportunity.

The next chapter provides an overview of risk assessment in terms of return calculations and explains the many ways to calculate returns.

Class questions for discussion and/or mini-case studies

Multiple choice

- A conservative use of options includes:

a. Uncovered call and put trading.

b. Covered puts.

c. Hedging of equity positions.

d. All of the above.

- There are three forms of value in options. These are:

a. Extrinsic, intrinsic, and time values.

b. Long-term, short-term, and perceived values.

c. Intrinsic, time, and actual values.

d. Volatility, risk, and time values.

- The risk in an uncovered call is:

a. Too great to be part of a conservative strategy.

b. Determined by whether the underlying security is owned.

c. Identical to market risk of a covered call.

d. Nonexistent because exercise will never occur.

Exercise for Discussion

Find an options listing for a stock and identify the levels of risk based on distance between the underlying price and the strike price of the option. Explain why these risks vary and identify the contract with the most conservative attributes.

1 Quality of earnings refers to the fundamental strength of the corporation and to its long-term growth potential. A high quality of earnings translates to greater prospects for long-term growth and fewer unpleasant earnings surprises. One definition of this term is “The amount of earnings attributable to higher sales or lower costs rather than artificial profits created by accounting anomalies such as inflation of inventory” (www.investopedia.com).