Spiraling Connections: The Practice of Repair in Bektashi Muslim Discourse

Wayne State University

Linguistic anthropologists have long recognized the great variety of speech communities and the perspective that research in different speech communities offers on discourse generalizations and findings (Brody, 1991; Duranti, 1988; Goodwin, 1981; Gumperz, 1982; Hill, 1995; Hymes, 1981; Ochs, 1988). They have also recognized the perspective that research in different speech communities offers on the social construction of cultural categories, for example, the social construction of incompetence as a Foucaultian sort of “dividing-practice,” often expressed in asymmetrical relationships of dependency in certain institutions of Western cultures. In this paper, however, I present a non-Western speech community wherein the central relationship promotes asymmetrical dependency but at the same time profoundly nurtures competence through language.

The purpose of the paper is thus to present cultural perspective on Western social construction of incompetence through language by analyzing interaction in a very different speech community. The speech community is that of a minority Muslim group dating from the 13th century, the Bektashis,1 whose devotion to their spiritual masters, and community-based mystic practices invite parallels with Hasidic communities.2 The central relationship is the age-old one of spiritual master and student, studied here in the religious center of an Albanian Bektashi immigrant community in America. The discourse data is taped weekly dialogues in Turkish with the spiritual master. Such dialogues have long been understood as a main medium of learning of the student with the master. The focus of analysis is the discourse feature of repair as described in Schegloff, Jefferson, and Sacks’ (1977) classic article as well as in Jefferson’s (1987) article on exposed and embedded repair, and how such repair figures in discourse data from 10 years of taped weekly dialogues with the spiritual master.

Repair is often an interactional strategy used to construct incompetence through replicating power asymmetries. The conceptual strength of the category of repair over simple correction is that repair includes self-correction and modification, as well as correction by another. And while the dialogues of master and student are framed by Bektashi tradition as non-confrontational in any direct sense, they are also understood to promote the self-confrontation that is deemed necessary for spiritual growth of the student. What then are the forms and implications of self-correction, other-correction, and repair-opportunity space in such ongoing interaction?

Besides the unusual cultural setting, the 10-year data set of interaction with the same master and student contrasts sharply with the multiple sources and contexts of interaction often cited in studies of repair (exceptions to this are Goodwin, 1990; Philips, 1992; Tannen, 1984). In contrast, the data of this study allows the possibility of studying repair within an evolving relationship over what is for linguists, albeit not historians, the longue durée. In one sense it poses the question to what extent our understanding of repair has been a reflection of data and analysis wherein relationships among participants are deemed irrelevant. In another ethnographic sense this study uses findings from Conversational Analysis on repair and their legalistic forms to contrast and foreground the Bektashi practice of repair.3

In presenting Bektashi practices of repair, I first relate dicta from Conversational Analysis on repair to Bektashi conventions and discourse formulations of interaction. Then I contextualize the immigrant Balkan Muslim community in the larger world of Islamic and Bektashi discourse, and the vulnerability of a student in a particular classic instance of repair by a Bektashi master. After that I present select examples of embedded repair and exposed repair of the master, student, and community. Finally, I summarize findings and speculate on the social construction of incompetence through language and what in Bektashi cultural practice mediates against its construction.

But first, to orient the reader to the Islamic Ottoman cultural world that Bektashi tradition draws from, and to give insight into attitudes toward public construction of incompetence there, I offer a cultural “translation” of a popular American game show by a culture that also draws from a common Islamic Ottoman past. The American game show is “Name That Tune.” Its translation, by the same name, which I witnessed on Turkish television in 1985, draws on the tradition of Turkish classical music that has been passed down from master to student in a fashion similar to the way religious knowledge is passed down among the Bektashis (who have long been Turkish-based). In the American form of “Name That Tune,” incompetence is socially constructed in that the multiple contestants, who are played selections of popular music to identify, are given a limited period of time in which to respond. Sometimes they do not know the tune, the buzzer sounds, and so their relative “incompetence” is made public. As for those who successfully identify the tunes, their performances are compared and they are given prizes whose cash value can also be compared across the program and across different programs.

In contrast, in the Turkish version the music is not popular music but rather modes from the classical musical tradition. Contestants are treated more like guests, they appear one at a time, and are not timed in their responses. There is no buzzer and no one is ever wrong. That is, no one ever makes an error of identification of a mode. Viewers may test themselves in the process, and thus may be privately incorrect, but there is no public display of incompetence. Finally, instead of prizes that can be accorded dollar values and compared, the participants receive the opportunity to perform, that is, to sing from a classical mode, on television.

The conclusion that I would draw from this contrast is not simply that no category of incompetence was constructed in the Turkish version. Rather I would suggest that aspects of the American format were rejected precisely because such categories of incompetence do exist in the Ottoman cultural world but are deemed more serious business. For an owner of a television station to invite people to participate in a way in which they could be publicly shown wrong would be a grave insult. Rather, what is missing is the ambiguous category from Western society of the value of “not winning but playing the game.” Indeed, in Ottoman culture historically there were contests of poets in which the loser lost not just the contest but also his head.4

CONTRASTING FORMULATIONS OF REPAIR: CONVERSATIONAL ANALYSIS AND BEKTASHI WAYS

As mentioned, repair is a common strategy for construction of incompetence through language. Consider, for example, a doctor’s correction of a patient’s reference to “low blood,” or an attorney’s correction of a client’s notion of slander, or for that matter, a judge’s correction of an attorney’s behavior—or even, for a more appropriate comparison, certain interactions of therapist and client (see Ferarra in this volume). Repair, however, includes not just correction by another, but also modification and most significantly self-correction.

The classic article on repair in Conversational Analysis by sociologists Schegloff, Jefferson, Sacks (1977) notes the important place of self-correction in “ordinary conversation” in the first two of its three dicta. (This preference for self-correction has been supported by Moerman, 1977, in Thai conversational data.) Notice also the third dictum for its reference to incompetence:

1. There is an organizational preference for self-correction.

2. Other-initiations overwhelmingly yield self-corrections.

3. Occurrence of other-correction is highly constrained, except in transitional situations of “not yet competent.”

As Bektashi discourse is centrally concerned with relationships—of master and student and human and God—it too has formulations relevant to discourse repair. But based on a much older and more oral culture, and one that does not suffer the weight of authority invested in Western scientific laws, Bektashi rhetoric is quite different from the above dicta. One of these relevant Bektashi formulations is the following aphorism told to me by Bektashi leader Baba Rexheb: “We would never pull the veil from anyone’s face.” Notice that whereas the Conversational Analysis dicta are phrased in the positive, the Bektashi aphorism is phrased in the negative, thereby leaving the larger field of what happens, either self-correction or no correction, unspecified. The implications of this Bektashi saying relate to questions of dignity, that one should never put another human in a position of indignity. In the highly oral culture of Bektashi societies, direct correction by another would often be seen as bringing indignity. Notice also the third dictum under Conversational Analysis. In cultural terms, the constraint on other-correction except in transitional situations of “not yet competent” is grounded in assumptions of progress and development. In contrast, the Bektashi student is understood to be always in transition in spiritual matters; nevertheless there is no public construction of incompetence.

Building on the category of other-correction, there have been further formulations from Conversational Analysis. In particular, Jefferson (1987) developed the distinction in other-correction between exposed and embedded correction, as follows:

exposed correction (whatever has been going on prior to correction is discontinued; correcting becomes the interactional business).

embedded correction (the correction is incorporated into ongoing talk).

In terms of Bektashi formulations relevant to repair, most refer to potential other-initiated correction, but more in terms of warning against drawing any public attention to perpetrators than in measures that differentially dilute this attention. For example, another type of Bektashi commentary relevant to questions of repair is associated with the most important piece of clerical garb, namely the hirka. The hirka is a long sleeveless vest that is traditionally worn by Bektashi dervishes (monks) and Babas (abbots). The outside of the vest is understood to symbolize the vow of poverty of dervishes, while the inside of the vest symbolizes the duty of Bektashi dervishes to “cover the sins of others.” Note that “covering the sins of others” is a positive formulation, stronger than the negatively formulated interdiction “not to pull the veil from anyone’s face.”

A short Bektashi tale serves to make clearer the meaning of the hirka commentary to “cover the sins of others.” The main personage of this tale is Imam Ali, who was both the son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad as well as the bringer of mystic understanding of the Qur’an, and was highly revered by Shi’a-oriented Bektashis.

One day Imam Ali was walking down a narrow road. On either side were dry brick walls that surrounded the courtyards of the houses. One wall was slowly falling down, however, and where a brick had fallen out, Imam Ali could see a man and woman in the courtyard of the home engaged in something they shouldn’t have been doing. Immediately the Imam picked up a brick from the road and put it in the hole so no one could see in, and then walked on.

Unlike other traditions wherein a similar situation led to the stoning of the woman, or at best the shaming of those about to carry out a stoning and then an admonition to the woman, here the Bektashi way is to literally cover the visual access to others’ behavior, to cover their sins without comment.

Yet another dictum of Conversational Analysis on repair (Schegloff, Jefferson, Sachs, 1977, p. 375) relates to the range, in terms of turns at talk, within which repair occurs: “The repair opportunity space is continuous and discretely bounded—three turns long starting from the trouble source turn.” In Bektashi discourse the closest parallel to turns at talk would be couplets, in their rich tradition of spiritual poetry and chants. But the notion behind the Conversational Analysis dictum, that repair occurs relatively close to the trouble source, is of little significance to Bektashi ways. Rather, what is more important is that at some time those who have been corrected recognize this.

For example, in the following Bektashi tale two villagers were on their way to give false testimony for payment in a large town. They stopped at a Bektashi Tekke, a sort of Muslim monastery, on their way and the Bektashi Baba immediately recognized the purpose of their journey. As they sat drinking coffee with the Baba, and no doubt after an appropriate amount of polite small talk, the Baba told them this story:

Far to the north in a Bektashi tekke there took place an initiation ritual of a new member. At the initiation, another member of the tekke recognized that the new initiate was a man who years earlier had stolen a horse from him. After the ritual and the time of muhabbet, or sharing of spiritual chants, the other member started hinting that there was a man among them who didn’t belong, one who had done ill in the past and never paid or come clean. The Baba interrupted this talk with other talk. But again the member hinted more broadly. Again the Baba tried to steer the conversation to other topics, yet the man persisted in stating that there was one there who had done something wrong in the past and who didn’t belong. The Baba then looked directly at the older member and said, “Here we do not mention such things. Here is not the place for such talk.”

The villagers recognized that the Baba knew of their plans. They left the Tekke and journeyed back to their village, abandoning their earlier intentions of giving false testimony.

This is a most discretely negotiated instance of repair. And while there could be seen to be a time constraint in terms of the proposed court testimony, in terms of repair what is important is the eventual recognition of the repair and its discreteness. In terms of Conversational Analysis, however, this then is an example of other-initiated self-correction. That is, the Baba initiated the repair, but the villagers were the ones who followed up on self-correction, all without public mention, that is, without having the veil pulled from their faces.

The Bektashi forms of commentary on repair are here expressed on the canvas of activities including but not restricted to spoken communication. In the following sections, the examples of master-initiated and student-initiated repair show how specific verbal interactions with the Baba are continuous with such commentary.

CONTEXT AND CLASSIC BEKTASHI PRACTICE MEDIATING FOREIGNER INCOMPETENCE

In the last section I reviewed formulations of repair in Conversational Analysis and contrasted these with related Bektashi discourse to familiarize the reader with the very different cultural world of the Bektashis, one that is vitally concerned with relationships and is orally sophisticated. The very fact of the existence of these Bektashi tales and commentary shows that Bektashi tradition has deemed such teachings worthy of attention. In this section I contextualize the particular community in the larger Muslim and Sufi traditions. I also give a classic example of repair by the Bektashi Baba in the context of my study with him.

The immediate setting of research for this paper is an immigrant community of first and second generation Albanians in southeast Michigan. Albanians are a Balkan people with strong oral traditions. Thanks to the technology of the telephone and to the cultural tradition of visiting as the primary social recreation, Albanians are able to live in different parts of the Detroit metropolitan area, but still interact as if they were in a much smaller town. There is a rich variety of discourse forms: from public rhetoric and eulogies by men to laments by women; from songs whose manner of singing represents the earliest polyphony in Europe to spiritual chants individually performed; from gossip and verbal jousting by both men and women to metalanguage about the many Albanian dialects of the mountainous lands where Albanians have long lived on the Western side of the Balkan peninsula.

The community is also Muslim, which adds to an already rich discourse world the special importance accorded the Arabic language by Islam and the Islamic discourse forms of commentary and prayer. Recall that the Qur’an is understood as the Word of God, and that the first pillar of Islam is the shehadah, or creed, whose reciting, with faith that “there is no God but God and Muhammad is His prophet,” is the essence of Islam as well as the oath of conversion. But even more important, the community is Bektashi Muslim, a minority Muslim Order from 13th-century Anatolia, renowned for its spiritual poetry.

Bektashism, like other Muslim Sufi or mystic Orders, affords its members a more personal expression of affiliation and love of God through community rituals and gatherings than is generally available to the Sunni or orthodox Muslim community. Indeed Sufi Orders, like Hasidic communities in Judaism, often stand as a sort of critique of a legalism that has developed in both Islam and Judaism at different times in their histories. Thus the Bektashis have great faith in their spiritual masters, whom they see as intercessors; they place less emphasis on only fulfilling external practices of the letter of the law. This antilegalism mediates against simplistic categorizations of incompetence. The Bektashis also have the distinction of having accepted women as initiated members since their beginning in the 13th century, as well as having a muted belief in reincarnation.

The anchor of the Bektashis is formed by their spiritual masters, who trace their authority through chains of previous spiritual masters; their sense of time is cyclical, as great spiritual masters are embodied again and again. Learning is through being with such a master. In line with this, the data set is taped dialogues with the Bektashi master Baba Rexheb (1901–1995), who lived the last half of his life in America. The language of the dialogues is Turkish, long the main language of this Anatolian Order and of its spiritual chants, but a first language to neither Baba nor myself. Indeed, Baba and I speak different dialects of Turkish, his being a West Rumelian dialect, mine an Istanbul dialect, although we both move into each other’s dialects on occasion. There is even a sense, after study together since 1968, that we have developed a common dialect, affected partly by our common Indo-European first-language backgrounds (Albanian and English), but more by the length of time spent together. The actual taping, however, was from the last 10 years of study, from 1984 to 1994. Thus the earliest taped dialogue represents some newness in getting used to the tape recorder, but not in terms of interacting with each other.

Across the tapes, certain conventions of master-student interaction stand out. First, it is up to the student to ask questions, to initiate inquiry. Secondly, the preponderance of talk is by the master; that is, the master talks, the student listens, but there is also give-and-take. Thirdly, it is the master who initiates closure, thereby eventually giving the floor back to the student should other questions arise. (For a fuller discussion of these conventions, see Trix, 1993.)

Considering the greater knowledge and authority of the master, the expectation would be that repair would tend to originate with the master. Indeed, this is a common occurrence, either when the master initiates repair and the student then self-corrects, or when the master initiates repair and then gradually builds on this repair. Of the first sort, where the master initiates repair and the student self-corrects, a memorable example took place early in my study with Baba.

We were reading together the poetry of Omar Khayyám, a Persian poet whose works are best known in the West through the broadly construed 19th-century English translations of Edward Fitzgerald (“a jug of wine, a loaf of bread—and Thou”). Although Baba knew Persian, I did not, and so we were reading these 11th-century poems in Turkish translation. Only, the Turkish translator had left many words in Persian. My reading aloud took on all the features of foreigner incompetence, worsened by my resentment of the translator for not translating more thoroughly. As I stumbled along, it seemed that most often the Persian words I didn’t know referred to “wine glass” or “wine cup” or “wine container.” I reached another Persian word I didn’t know, looked at Baba, and said in Turkish “wine vessel?” Baba looked at me and then said in Albanian, “Fes të kuqë Libohovit?” That is, “Are all who wear red fezzes from Libohova?” Then he sat back, took his prayer beads, or tesbih, from the pocket of his hirka, and told me the following story:

Once there was a shepherd from near Libohova [a town in southern Albania]. Now, you know that in the Ottoman Empire at this time men wore red fezzes, except that on the Western edge of Empire, the Albanians had long worn white felt caps. Only in one town in Albania, in Libohova, the men wore red fezzes, for they had men from their town who had served in the imperial judiciary and were proud of their connection to the center of power.

Well, this shepherd, who had never been beyond the next mountain, was drafted into the Ottoman army and sent to, of all places, the capital city of Istanbul—“Dar es-Saadet” [an old Ottoman name for Istanbul, roughly, “the Abode of Happiness”]. After several years in the army, the shepherd returned and people asked him what Istanbul was like. The shepherd responded, “I never knew there were so many people from Libohova.”

In making every unknown Persian word a wineglass, I had been like the Albanian shepherd who saw every man in a red fez from his provincial frame of reference. But in explaining the parallel, I have left out the pleasure, for both Baba and I laughed. And from that day on we shared a way of referring to other situations where frames of reference were too constricted, and always it was with merriment, building on our earlier shared experience. In terms of Conversational Analysis, this represented an exposed form—we had left off the earlier topic of the poem by Omar Khayyam to focus on the “correction”—and an other-initiated repair at that. But like the villagers who had changed their plans from giving false testimony, mine too was a self-correction. Baba initiated it, but I recognized myself in the shepherd. Of course this “exposed other-initiated self-correction” is known in older parlance as the time-honored genre of parable. Thus, far from constructing incompetence through a direct correction of my error, the Bektashi repair strategy instead allowed me to recognize my situation in the parable. That I was able to do this was a positive experience, and through this, Baba’s and my relationship was strengthened and another memorable connection of shared experience created.

RANGE OF FORMS OF REPAIR: EMBEDDED, EXPOSED, OVEREXPOSED

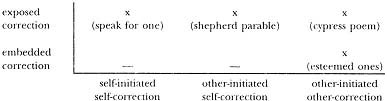

The preceding example of Bektashi repair through telling the parable of the shepherd was described in Conversational Analysis terms as an exposed form of other-initiated self-correction. In Figure 7.1, which summarizes the range of potential repair forms described by Conversational Analysis (CA), the shepherd parable is marked. Notice that this figure is organized is such a fashion that the further to the right and the higher up the gradients, the greater the potential indignity or marking of incompetence. That is, exposed other-initiated other-correction poses much greater indignity potential than embedded self-initiated self-correction.

FIG. 7.1. Potential repair forms and distinctions from Conversational Analysis (marked to show major examples of this study).

Notice also that I do not focus on embedded self-initiated self-correction, or embedded other-initiated self-correction—forms of repair that are often the bedrock of repair studies and certainly have important ramifications for syntax studies (Fox et al., 1996). This is not to say that these do not occur in the 10 years of taped interactions with Baba. Indeed, they are most frequent. However, I choose to focus on the other forms of repair because they are more relevant to questions of creating categories of language incompetence.

What is missing from the Conversational Analysis repertoire is notice of relative levels of authority of the self and other. This is consistent with Conversational Analysis’ lack of interest in backgrounds of interactants. The default assumption is that they are peers, of equal status and authority. That is not at all the case with Bektashi master and student, nor is it the case in many other situations. For example, it matters greatly whether it is the attorney who corrects the judge or the judge the attorney. To compensate for this missing parameter, I always note whether the corrector is master or student, and include a section on the delicate matter of correction of the master by the student. But I begin with more common forms of repair that potentially lead to the creation of incompetence, namely embedded other-initiated other-correction.

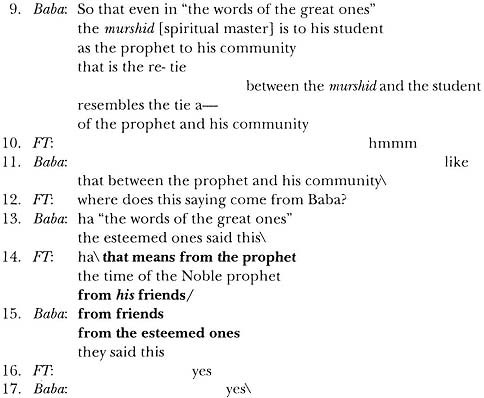

Baba’s embedded other-initiated, other-corrected repairs of my comments only emerged when I transcribed5 tapes of the dialogues; I had not been aware of them during their occurrences. One example of such an embedded repair, which I have translated from Turkish, took place in November 1985. My error was a confusion of the phrase, “esteemed ones” (13th-century spiritual teachers from the time of the organizing of the Sufi Orders) with a separate phrase denoting “friends of the Prophet,” that is, friends of the 7th-century Prophet Muhammad. (Numbers to the left of the transcriptions refer to turns at talk. Here they show that this section was relatively early in the discussion.)

Transcription 1: Embedded Master-Initiated Master-Correction

Notice how Baba does not bring to my attention that I am only off by 600 years. Rather, he repeats a general word of mine, “friends,” without the incorrect “of the Prophet,” and then restates the correct term, “the esteemed ones.” Then 36 turns later, Baba again cites the aphorism, “the murshid is to the student like the prophet to his community,” only here he directly ascribes this to early Bektashi spiritual leaders. Since the Bektashi Order was founded in the 13th century, this clearly places the source of the quotation. According to strictures of Conversational Analysis this cannot be a repair because it is farther than three turns from the trouble source. A counter argument would be that dialogue of master and student is not ordinary talk, and yet it is very frequent and not at all stilted. Rather, I would say that to be able to identify repair at greater distances, the context of talk and interactants must be taken into consideration. In terms of questions of construction of incompetence, however, what this form of repair shows is a preference for subtle correction that may or may not be picked up, and an avoidance of direct correction.

Another somewhat less common form of repair in dialogues with Baba is exposed self-initiated self-correction by the student. A particular example I have of this on tape took place over a 2-year period and centered around the meaning of the phrase “to speak for someone.” In the first instance of this on tape, in the context of Baba telling me the life story of Ali Baba, the Head Baba was encouraging a young Ali Baba to go back to Albania to a city known for its cantankerous people. The Baba promised “to speak for” the young Ali Baba, and always to be with him. I assumed the phrase meant that the Baba would “supply him with words” whatever the situation. However, when there indeed arose a difficult situation for Ali Baba in Albania, he didn’t make any speeches or use any special words.

Two years later, Baba again told me the story of the life of Ali Baba of Elbasan. In turn 83, Baba noted the Head Baba saying that he would “speak for Ali Baba” should the occasion arise. In turn 114, there is a plot hatched against Ali Baba in the town in Albania, and the Head Baba back in Turkey pauses with his coffee cup in hand, doesn’t drink, just stands there, then announces to the others present that Ali Baba was in a dangerous situation but that now he is safe. A dervish who is present writes down on a piece of paper that on such and such a day the Head Baba said this, and then he puts the piece of paper in his headpiece. Years later Ali Baba goes back to the Bektashi headquarters in Turkey, where he encounters the dervish who much earlier had noted the Head Baba’s strange behavior and comment.

Transcription 2: Exposed Student-Initiated Self-Correction

Baba’s words in Transcription 2 are the third reference to “speaking for someone” in the taped session. Only here, Baba used a different preposition, “with.” Already there was some question in my mind of what the phrase meant, for in the difficult situation in Albania, Ali Baba didn’t make any speeches. Here though I had a hypothesis, unlike my earlier notion in 1984 and 46 turns earlier in this session where I still assumed that “speaking for someone” meant “giving someone the necessary words.” Here I asked if “speaking for someone” meant speaking to God (the “Majesty of Truth” is the Bektashi mystic term for God) for that person, that is, “praying for them.” Baba confirmed that this was the meaning he intended.

What does this example represent for repair opportunity space? Recall that in Conversational Analysis the repair opportunity space is given as up to three turns from the trouble source. Here the immediate trigger for my self-correction in Transcription 2 was Baba’s previous turn, but this was only part of the picture. The tendency is not to interrupt Baba with questions, but along with this, the tendency is for discussions to recycle, so that stories told are told again, often from different perspectives and with added episodes. This spiraling of story and reference over time encourages rethinking of understanding, such that the repair opportunity space, which in Conversational Analysis is deemed as at most three turns from the trouble space, warrants extension.

In the above example of Transcription 2, the trigger for my repair is indeed Baba’s previous turn, but what is corrected was my assumption of what it meant to “speak for someone,” an assumption probably first held when Baba first told me the story of Ali Baba’s life years earlier. On tape there is a reference two years earlier, and in this tape, a reference 46 turns earlier and 15 turns earlier. It would be a diminished human whose reflections only lasted up to three turns.

The situation of learning in Bektashi practice is a stretching in the other direction, where a goal is to become insan-i kamil, that is, “the perfect human”—all that the image of the Majesty of Truth within us makes us long for. Only, as Bektashi discourse also notes, we are “like an ant going on pilgrimage.” How far can we go? As far as we are given strength. But even this ant goes beyond three turns.

Besides student-initiated self-correction, there is also the more problematic student-initiated repair of the master. The power asymmetry of master over student would predict that this would be the least likely sort of repair strategy. From examination of the tapes, such instances do occur, but invariably with some form of modulation, like “excuse me” in the formal second person, along with reference to Baba’s title. Another stricture of these forms of repair is that they occur at places of transition, most notably after Baba has signaled initial closure of a discussion. If these two strictures were omitted there could potentially be another form of incompetence constructed—not the usual one where power asymmetries are replicated but one where they are overthrown. As parents of teenagers may experience, this too can lead to forms of incompetence.

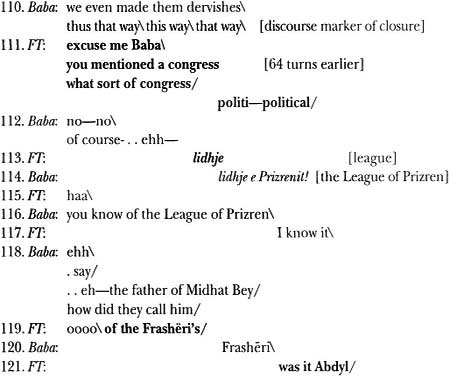

The following example of exposed student-initiated student-correction of the master took place late in 1994, at a transition place near the end of the taped interaction. The correction referred back to an unsuccessful double name search Baba had voiced 64 turns earlier, when he sought the name of a congress and name of its organizer. Again, this counters the Conversational Analysis dictum that repair be conducted within three turns of the trouble source. But unlike the earlier example of correction of the notion of what it meant for a Bektashi Baba to “speak for someone,” here there is no apparent trigger.

Transcription 3: Exposed Student-Initiated Repair of Master

Here, after Baba had summarized the point of the main narrative of our previous talk, I was able to call up Baba’s first unsuccessful name search from 64 turns earlier and give half of its formal designation, lidhje (“league”), in Albanian. Baba immediately picked up on this. He then recalled his second, much earlier unsuccessful name search, which he had had regarding the organizer of the congress. He even remembered the name of the organizer’s son, to which I was able to provide both the family name, “Frasheri,” and the first name of the father, “Abdyl.”

The placement of the exposed student-initiated correction, after the main body of the interaction and Baba’s reiteration of the main point, followed by his discourse marker of closure (“thus that way this way that way”), is significant. As mentioned earlier, one of the conventions of interaction, attested to throughout the 10 years of dialogues and presumably earlier, is that it is the master who draws dialogues to a close through various discourse markers and strategies. After the master’s signal for closure, the student often affirms the closure and then the master confirms this affirmation. Other forms of affirmation are most often connections of earlier associations that I have with the topic of discussion, often from earlier dialogues. Thus, the above correction of the student can be categorized by its location as part of the larger category of connection, only here what was connected was an earlier question of the Baba within the same discussion.

There remains the category of repair of greatest potential indignity, of exposed other-initiated other-corrected repair. This is the form of repair most likely to lead to construction of incompetence. In the following example of this sort, I go beyond Jefferson’s (1987) notion of “exposed,” as having the correction become the focus of attention, to a community notion of “exposed,” meaning “made public fun of.” The interaction leads to the reiteration of the social category of foreigner, a common model of incompetence constructed through language.

The incident occurred in the early 1980s before I had learned much Albanian. I was at the Michigan Bektashi Tekke in the basement, helping the women prepare ritual food for many hundreds of people for the major Bektashi holiday the next day. There were large cauldrons for cooking this food, only they were stored up high in the basement cupboards. As I reached up for one I noted, in my faulty Albanian, that I was “longer” than any of the women there. Immediately I was greeted with cackles by the older Albanian women. All repeated my words of my amazing length. Of course, I was trying to say that I was “taller.” For the rest of the day my words got repeated to much amusement. By the evening, the joke had worn thin. Then at the dinner table, before the meal—a special time of sharing and of poetry and meze, or hors d’oeuvres—again my words were repeated to Baba.

He sat back, closed his eyes, and chanted to me in Turkish the third stanza from the famous 16th-century poet, Pir Sultan Abdal:

Transcription 4: Exposed Master-Initiated Repair of Other-Initiated Other-Correction

Benim uzun boylu servi cinarim,

Yüreğime bir od düştü yanarim,

Kiblim sensin yüzüm sana dönerim,

Mihrabimdir iki kaşin arasi. hu

* * *

My tall and graceful cypress, my plain tree,

A fire strikes my heart, I blaze,

Toward you I pray, I turn always facing you

My prayer niche is between your two brows. hu

The connection was the Turkish phrase in the first line meaning “tall.” But the connection was more than that, for what Baba had done was take my uncomfortable situation and tie it to a poem he loved, a poem that ever after would be mine as well. It was a repair of a repair; that is, Baba was repairing the correction the whole community had been making all day of my Albanian, and the incompetence I had come to feel as outsider. Baba’s repair transformed my embarrassment to pleasure and drew me into the world of Bektashi discourse, long famous for its spiritual poetry.

In so doing he strengthened our relationship and broadened my world of reference. For such connections would I gladly fall on my face again and again.

CONCLUSION

What does this study of the Bektashi practice of repair contribute to understandings of repair and of the social construction of incompetence through language? The last example is the most memorable. In it Baba transformed community attention to my early incompetence in Albanian—a construction of foreignness through language—to connection with him and the Bektashi tradition of mystic poetry. In all fairness though, the immigrant community whose members effected this public construction of incompetence live on a daily basis, in work and bureaucratic situations, with constant construction by English speakers of their incompetence. Yet Baba, their community leader, corrected their initiation and correction of my error with reference to a tradition that recognizes no ethnic boundaries. A strength of Bektashi tradition, one that has made it especially effective in missionary work, is precisely this sort of overarching practice.

It is at the level of practice that Bektashi tradition can be related to findings of Conversational Analysis on repair. Here there is significant overlap. Where Conversational Analysis asserts the preference for self-correction; Bektashi practice abounds in instances of self-correction, not just at the morphological and phrasal level, but also at higher conceptual levels. Where Conversational Analysis distinguishes embedded and exposed repair strategies; Bektashi practice too shows examples of embedded other-initiated correction of the graduated form, as well as exposed other-initiated correction of parable form.

The main disparity between the Conversational Analysis findings on repair and those exemplified in the data of Bektashi master and student, apart from rhetoric, lies in repair opportunity space. Where Conversational Analysis asserts that correction takes place within three turns of the trouble-source turn, Bektashi practice includes correction at distances of 36 turns (Transcription 1), 46 turns (Transcription 2), or 64 turns (Transcription 3). Some faulty assumptions can even be traced back several years. This longer distance of repair opportunity space in Bektashi practice relates only partly to the convention of reticence in interrupting the master’s discourse and to the convention of the student’s formalized place of participation after the master’s initiation of closure. These conventions serve to heighten attention in the student, as ideas tend to be held longer before they can be referred to or queried.

The spiraling of stories and interlocking narratives across years of study and across single periods of interaction further facilitate such attention and the possibility for later corrections. This spiraling provides the student with appropriate material for affirming the closure of the interaction. This spiraling of stories also allows for reframing of understanding, often times self-corrections, where later narratives make clearer the point of narratives told much earlier. The wealth of shared experiences of previous interactions and the relatively long duration of Bektashi master and student relationships further contribute to the stockpile of potential connecting and redefining references. These can provide scaffolding for more complex ideas and the refining repair of the student’s spiritual understanding.

These Bektashi conventions—specific discourse features of master and student talk, the spiraling of stories over time, and the relatively long relationship of master and student—although they are from somewhat specialized interactions, still shed light on assumptions of interaction of “everyday talk” in Conversational Analysis research. In particular, it appears that the data of Conversational Analysis is from interactions where, unlike the Bektashi master and student, the participants have generally equal claim to the floor. It also appears that the interactions from which Conversational Analysis draws its data do not have broader pedagogic purpose and could involve virtual strangers. Indeed, the question arises to what extent the emphases on morphosyntactic and phrasal repair across a short number of turn sequences reflect the disjointed nature of many data sets in Conversational Analysis. It is intriguing to speculate whether researchers’ lack of concern with ongoing relationships among participants in data of Conversational Analysis is the crucial constraint that bars recognition of repair at greater distance than three turns. But then, the focus on adjacency pairs and close sequences that has characterized Conversational Analysis’s pursuit of an organizational architecture of talk,6 may also blind it to the possibility of longer-distance repair.

With reference to the social construction of language incompetence, recall that at the outset of this chapter I characterized the Bektashi speech community as a sort of contrasting example, one wherein power asymmetries led not to the construction of language incompetence but rather to the nurturing of language competence in a profound manner. This is the Bektashi community at its best, with particular attention to master-student relations. The example of the community derision of my early Albanian provides a valuable counterexample, a context to which Bektashi practice by the leader offers critical commentary. Regarding this context, recall again the example of the culturally linked Turkish game show through which I tried to demonstrate that the cultural context is not one unaware of possibilities of construction of incompetence, but one most wary of such possibilities. One way to guard against such constructions is with clear delineation of role, as with uniforms and ornaments in the military, or vestments among the clergy. These markers serve to narrow appropriate behavior of those confronting the wearers of the garments as well as the behavior of those wearing them. Of course language is the greatest garment of them all.

In American society, however, our concern is more often with construction of incompetence in those not allotted special higher-status clothing, people whose incompetence is often generated through evidence of marked forms of their language. These are the people most subject to “footing” shifts, as Goffman put it (1982)—that is, abrupt changes of alignment in interaction that involve loss of individual identity and merging with a class of, say, “the young,” or “female,” or “minority,” or “teenager,” or “foreigner,” or “incapacitated,” or “old,” or any combination of these. Mediating against such downward shifts of categorization in our society is long-term interaction with an individual wherein novel dialects and communication patterns may develop, or personal development in an individual’s ability to pull himself or herself into another, better-regarded category through schooling, work, and financial resources—these last again expressed through expansion of language repertoires.

In contrast, in the Bektashi tradition of master-student relations, which serves as a model for the larger Bektashi speech community, long-term interaction is the norm, whereas personal development apart from this interaction is irrelevant. The student studies with and serves the master until the master dies. The language of any import is their language of communication. The master continues to intercede for the student after death—there is teaching beyond the grave. Western notions of agency and personal development as grounds for construction of competence are clouded by the understanding of outcomes as based on intercession of earlier spiritual masters, not achievement of individuals in the here and now.

In such a speech community and particularly in the discourse of master and student, repair and correction fall within the larger category of connecting—of connecting the student with the master, as exemplified in the parable of the red fez, and connecting the student with the larger world of Bektashi discourse, as exemplified in Baba’s matching a 16th-century Bektashi spiritual poem with the community’s correction of my error in Albanian adjective choice. In the larger spiritual frame, the repair that the master works to effect is a connecting not with a discourse trouble source but with the source of our being, a sort of “darning of the universe,” since in this life we have all been separated from our true source. In Hasidic terms, there is the notion of repair as “tikkun,” the mending and transforming of this imperfect world.7 In linguistic terms, what matters is communication most personally entered into and yet expressed through the sharing of Bektashi spiritual poetry (Trix, 1993).

Recall yet again the Turkish cultural translation of the American game show, “Name That Tune,” whose focus involved classical Turkish music. In the Turkish form this game demonstrates, as in the Bektashi tradition of learning, a spiraling of listening and performing, of passing on tradition with careful avoidance of creating categories of incompetence. Like the student in the Bektashi tradition, the direction is to replicating the tradition, the emphasis on connecting with that tradition, not defining its boundaries by those publicly constructed as incompetent.

REFERENCES

Birge, J. (1965). The Bektashi order of dervishes. London: Luzac & Co.

Brody, J. (1991). Indirection in the negotiation of self in everyday Tojolab’al women’s conversation. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 1(1), 78–96.

Duranti, A. (1988). Intentions, language, and social action in a Samoan context. Journal of Pragmatics, 12, 13–33.

Feinberg, H. (1972). Teacher and student in Buber’s Hasidic tales. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Department of Education, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

Fox, B., Hayashi, M., & Jasperson, R. (1996). Resources and repair: A cross-linguistic study of the syntactic organization of repair. In E. Ochs, E. Schegloff, & S. Thompson (Eds.), Interaction and grammar. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Goffman, E. (1982). Footing. In Forms of Talk (pp. 124–159). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Goffman, E. (1967). Interaction ritual. New York: Pantheon Books.

Good, D. (1990). Repair and cooperation in conversation. In P. Luff, N. Gilbert, & D. Frohlich (Eds.), Computers & conversation (pp. 133–150). London: Academic Press.

Goodwin, C. (1981). Conversational organization: Interaction between speakers and hearers. New York: Academic Press.

Goodwin, M. H. (1990). He said she said: Talk as social organization among black children. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Gumperz, J. (1982). Discourse strategies. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hill, J. (1995). The voices of Don Gabriel: Responsibility and self in a modern Mexicano narrative. In D. Tedlock & B. Mannheim (Eds.), The dialogic emergence of culture (pp. 97–147). Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Hymes, D. (1981). In vain I tried to tell you: Essays in Native American ethnopoetics. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Jefferson, G., (1974). Error correction as an interactional resource. Language in Society, 2, 188–199.

Jefferson, G. (1987). On exposed and embedded correction in conversation. In G. Button & J. R. E. Lee (Eds.), Talk and social organization (pp. 86–100). Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters Ltd.

Moerman, M. (1977). The preference of self-correction in Tai conversational corpus. Language, 53, 872–882.

Ochs, E. (1988). Culture and language development. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Philips, S. (1992). The routinization of repair in courtroom discourse. In A. Duranti & C. Goodwin (Eds.), Rethinking context (pp. 311–322). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Said, K. (1970). Ali and Nino. New York: Random House.

Schegloff, E. (1987). Recycled turn beginnings: A precise repair mechanism in conversation’s turn-taking organization. In G. Button & J. R. E. Lee (Eds.), Talk and social organization (pp. 70–85). Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters Ltd.

Schegloff, E. A., Jefferson, G., & Sacks, H. (1977). The preference for self-correction in the organization of repair in conversation. Language, 53(2), 361–383.

Sharrock, W., & Anderson, R. (1987). The definition of alternatives: Some sources of confusion in interdisciplinary discussion. In G. Button & J. R. E. Lee (Eds.), Talk and social organization (pp. 290–321). Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters Ltd.

Steinsalt, A. (1993). The tales of the Rabbi Nachman of Braslav [retold with commentary]. London: Jason Aronson.

Tannen, D. (1984). Conversational style: Analyzing talk among friends. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Trix, F. (1993). Spiritual discourse: Learning with an Islamic master. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

1 The best source on the Bektashis in English is still Birge (1937).

2 There are many sources on Hasidism and on particular Hasidic masters. Fewer, however, focus on the student-master relationship. Of these, an interesting one, albeit based on the secondary source of Martin Buber, is Feinberg (1972).

3 Other possible ways of analyzing Bektashi nonconstruction of language incompetence could be with reference to positive and negative politeness, deference and demeanor a la Goffman (1967), or even the concept of “face” in different cultures. However, I prefer the contrast with repair in Conversational Analysis for two main reasons. First, Conversational Analysis is firmly grounded in data that readily compares with my discourse data. Secondly, the unabashedly Western scientific form in which findings of Conversational Analysis are expressed provides a most telling contrast with how Bektashi ways are expressed.

4 For a 20th-century view of these contexts, one in which the winner took the lute of the loser rather than his head, see Kurban Said (1970).

5 Transcription is according to modified conventions of Discourse Analysis transcription, similar to those of Tannen’s book on conversational style (1984).

6 For an interesting discussion of a sociologist’s perspective on the sociological framework of Conversational Analysis as contrasted with the linguistic framework of Discourse Analysis, see Sharrock and Anderson (1987).

7 See Steinsalt (1993, pp. xxii, 1993) for Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav’s (1772–1810) understanding of the use of folktales as a form of tikkun, or “repair of the world,” as a way of raising up divine sparks for the redemption of the world.