Social Role Negotiation in Aphasia Therapy: Competence, Incompetence, and Conflict

Southeastern Louisiana University

University of Southwestern Louisiana

Speech-language therapy is a complex, goal-directed activity undertaken to improve an individual’s communication. Interestingly, by traditional design speech-language therapy harbors an inherent paradox. The goal of therapy is to build communicative competence, yet the assumptions required for treatment demand that the client be incompetent. That is, the therapist expects the client to demonstrate problems with communication. Thus, both parties act in accordance with a presupposition of deficit in the individual targeted for therapy (Damico & Simmons-Mackie, 1996; Kovarsky & Maxwell, 1992; Panagos, 1996; Ripich, 1982; Simmons-Mackie, Damico, & Nelson, 1995). In keeping with this presupposition, the clinician and client implicitly adopt necessary roles as competent expert and incompetent patient in order for therapy to proceed in an orderly and efficient fashion.

The social contract that establishes these roles of competent helper and incompetent person in need of help is instilled through a variety of means. Physical aspects of the setting establish the speech-language pathologist as an expert (Kovarsky, 1989a; Simmons, 1993; Simmons-Mackie, Damico, & Nelson, 1995). For example, characteristic architectural layout, furnishings, and modes of dress dictate an obvious authority hierarchy. This recognizable context dictates prescribed discourse patterns in much the same manner as the authority-biased context of the courtroom (Panagos, 1996). In addition, verbal and nonverbal interactive dynamics of therapy reinforce the social contract between the helper and the one in need of help (Damico & Damico, 1997; Damico & Simmons-Mackie, 1996; Simmons-Mackie, Damico, & Nelson, 1995). For example, components of discourse, such as elicitation of known information, challenge questions, and therapist evaluations, reinforce these roles (i.e., Silvast, 1991; Simmons-Mackie, Damico, & Nelson, 1995; Wilcox & Davis, 1977).

Assumption of the roles of expert and patient is a necessary aspect of the therapy encounter. In order to fulfill the mediational goals of therapy and proceed forward in an orderly and efficient manner, both parties in therapy conform to standardized routines. However, rigid role casting and an inflexible adherence to the structure of therapy can blind the “expert” to the remarkable competence displayed by clients. In such instances, the imposition of the initial social roles of the helper and the one in need of help may prevent the emergence of other social roles that reveal greater competence in the client during therapy. Thus, a paradox occurs when rigid compliance with designated roles (a) prevents the therapist from appreciating highly competent aspects of a client’s communicative behavior, and (b) places the client in the position of adhering to the role of incompetent patient (Kovarsky & Maxwell, 1992).

The remarkable stability of these social contracts adopted in therapy is illustrated through a conversational analysis of an argument between a person with aphasia and her speech-language therapist. The argument provided an interesting contrast with a standard therapy session. The comparison reveals several ways that social interaction in therapy is determined, highlighting the established roles of therapist and patient. Furthermore, the session provided an opportunity to view the person with aphasia both as “incompetent patient” and, in an alternative role, as “competent consumer” within one situation. Such an opportunity emphasizes the complexity of the collusion that takes place within therapy to create social roles.

PARTICIPANTS AND DATA

C, a 50-year-old woman, sustained a left-hemisphere CVA in May 1991. Prior to her stroke, C had been an office manager. She was divorced, self-supporting, and lived alone. Her friends described her as outgoing and independent. After her stroke, C was diagnosed with severe aphasia and apraxia of speech. Initially, her auditory comprehension was moderately impaired and verbal communication was virtually nonexistent. C was enrolled in speech-language therapy in a hospital-based rehabilitation center. She slowly improved until she was able to communicate in single words and short phrases accompanied by gesture and some writing. Scores on the Porch Index of Communicative Ability (Porch, 1981) administered in July 1992 placed C in the 72nd percentile of individuals with aphasia, with a mean score of 12.63. Verbal communication was nonfluent and agrammatic; she primarily produced content words (e.g., nouns, verbs) with a mean length of utterance (MLU) at about 3.5 word forms. During the spring of 1992, C became increasingly concerned about her slow progress in therapy. Her concerns also related to her poor insurance coverage for speech services, and her inability to pay for the services herself.

L was C’s speech-language pathologist. L was a certified speech-language pathologist with over 5 years of experience with adult aphasia. She was well respected by her peers as an aphasia clinician.

The first video-recorded therapy session occurred in January 1992, approximately 8 months after C’s stroke and 2½ months after L and C had started working together. The session was 56 minutes long and yielded 229 turns. There were two treatment tasks. One task focused on auditory comprehension of two-step commands. The other task involved verbal and written picture descriptions. According to the participants, this was a typical treatment session.

The second recorded session occurred in April 1992. This session lasted 11 minutes and comprised 108 turns. Therapy in the second session focused on written and verbal descriptions of commercially available picture cards using an adaptation of Response Elaboration Training (Kearns, 1985). For this task the therapist directed the client to describe a picture, elaborate on the description, then write the elaborated description. This session ended with an argument between L and C.

Both sessions took place in L’s office/treatment room in a hospital clinic. L and C were seated directly across from each other at a table. Sessions were videotaped, transcribed using an adaptation of the Jefferson transcription system (Sacks, Schegloff, & Jefferson, 1974), and analyzed via conversational analysis procedures (i.e., Goodwin & Heritage, 1990; Psathas, 1995). The transcription of the argument is included in the Appendix.

THERAPY AS AN INSTITUTIONALIZED ROUTINE

It is from within the routinized therapeutic context, with its well-defined and expected roles, that the changes discussed in this chapter are most apparent. In the data examined, several aspects of the therapy interaction appeared to be standard features, which served to reinforce the underlying social contract and therapeutic goals.

Establishing the Structure of Participation

Both aphasia therapy sessions began with a period of casual conversation that conformed to textbook recommendations of an initial phase of adjustment and rapport building (Brookshire, 1992; Porch, 1994). The casual conversation consisted largely of the therapist asking questions and the client providing simple answers (primarily yes–no). The therapist effectively controlled and promoted turn sharing (albeit somewhat asymmetrical), which guaranteed continued talk. C provided simple responses and accepted allotted time slots. In effect, the participants cast a casual conversation into a loose form of elicitation sequence in which L asked and C responded. While both L and C participated in this repartee, C did not introduce topics, expand on topics or attempt to demonstrate complex language competence. Rather, L provided “slots” for C to fill with simple answers. As Panagos (1996) suggests, it is the role of the therapist to keep the session moving forward. L successfully moved the conversation along with no difficult repair sequences or misunderstandings typical of C’s nontherapy conversational interactions. The impression was that of a casual conversation controlled and facilitated by the therapist. Thus, the therapist controlled the participation structure of therapy and promoted the flow of activities. In these ways the social contract between therapist and client was clearly negotiated during this opening phase.

Establishing the Therapeutic Framework

After the opening phase of both sessions, therapy tasks were introduced by the therapist using a specific structural framework. The task introduction in the first session is shown in Example 1.

| 63 | L: | Okay. I’m gonna put 10 pictures out. |

| 64 | Awright. These are our pictures that we work with off and on | |

| 65 | and I’m gonna ask you to point to two things for me. | |

| 66 | Okay. Remember how much better you did with this on Monday? | |

| 67 | C: | Yeah |

| 68 | L: | All right. Show me the chair and the brush. |

| 69 | C: | ((points to the chair and brush)) |

A similar introduction to the second session is found in Example #2.

| 32 | L: | Okay. All right. Let’s run through ((clears throat)) |

| 33 | and look at our pictures. | |

| 34 | Remember we had pulled 10 pictures out? | |

| 35 | I’m gonna kind of mix ’em up a little bit. | |

| 36 | Urn::: I want you to tell me in as many words | |

| 37 | as you can, tell me what’s happening in the picture. ((places picture on table)) | |

| 38 | C: | The c couple is bed in. What isy:: ((points to picture)) |

Although the therapy tasks in each session are different, the similarity in basic format and style are revealed in the therapist’s introduction. Each introduction begins with a discourse marker (“Okay,” “Okay. All right”), which signals a shift from the opening phase to the beginning of a treatment task (Kovarsky, 1989a, 1989b, 1990). The therapist, not the client, establishes this shift to the treatment task.

Next, the therapist employs several alignment strategies to enlist the client’s cooperation with the task. First, the therapist joins herself with the client pronominally as in Example 2, lines 32–34 (let us, our pictures, we had pulled). This brings therapist and client together as an established team with a joint past. The therapist further capitalizes on their joint history with “remember we had pulled 10 pictures out” and orients the client to the task. This royal “we” reinforces the roles already established and reminds C of her past cooperation with the task and acquiescence with the format of therapy. In effect, the structure and content of this introduction grounds the activity in a background of past cooperation in keeping with the social contract.

Having marked a shift in structure and established a basis for alignment and cooperation, the therapist moves on to request performance by the client: “I’m gonna ask you to point to two things for me” (Example 1, line 65) and “I want you to tell me” (Example 2, line 36). The therapist, in effect, requests displays of client performance. Such behaviors signal that the therapist has the right or power to dictate; a clear signal of her authority role (Maxwell, 1993). C’s heightened attention, compliance with requests, and virtual absence of counterrequests signals collaboration in this distribution of control, and willing assumption of the “patient taking the cure” role. L’s use of personal pronouns in the directives (I want, for me, tell me) creates another strong solicitation for cooperation with the social contract. These “do it for me” constructions by the expert authority are powerful exhortations for C’s fulfillment of L’s expectations. In addition, the wording “I want you to” (expressed as a desire) and “I’m going to ask you to” (a plan of action) are softer and less imperious than a raw command. Research suggests that speakers often temper requests using polite constructions, or cast requests as opinions (I think you should …), in order to minimize the chance of a refusal (Brown & Levinson, 1978; Button & Lee, 1987; Schiffrin, 1990). Furthermore, these constructions, when used in a routinized manner, signal the beginning of a familiar series of turn constructional units allowing C to prepare for her standard part in the interaction. Thus, the discourse shapes, and is shaped by, the social roles associated with aphasia therapy.

Finally, the heart of the treatment task is characterized by a triad of adjacency units initiated by a therapist request or question. This usually takes the form of a directive, such as “Show me the chair,” or a question, such as “What is the name of this?” Both directives and questions constitute requests to perform. For example, the intent of the question “What is the name of this?” is to request labeling performance.

In nontherapy discourse there are several possible responses to a request (Schiffrin, 1994). The person who receives the request can comply with the request (or attempt to comply), refuse to comply with the request, or derail the request (such as asking for clarification or changing the topic). The following adjacency units are typical of natural discourse: (a) request–fulfill request (or attempt to fulfill request); (b) request–reject request; or (c) request–derail request.

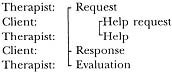

During speech-language therapy, however, the only option available to the client is the first—to fulfill the request. A therapist’s request is followed by a client’s attempt to comply with that request. The client’s response is then followed by the therapist’s evaluation of the response. This produces an adjacency triad consisting of request-response-evaluation (RRE).

If the client is unable to perform the task due to deficit or does not understand the task, then a side sequence ensues in which the therapist offers help to insure that the client performs the task successfully, ultimately completing the RRE sequence as follows:

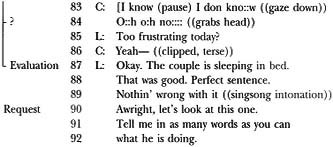

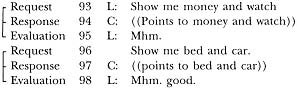

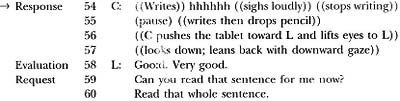

Although the content of RRE sequences varies considerably, the structure of this three-part adjacency sequence is relatively invariable. Once initiated, each party is constrained to fill the slot for the next part of the triad. Several researchers have identified the presence of request (initiation)-response-evaluation sequences in child therapy and classroom discourse (i.e., Bobkoff, 1982; Duchan, 1993; McTear & King, 1991; Mehan, 1979; Ripich et al., 1984). This pattern of request-response-evaluation (RRE) is pervasively evident in C’s language therapy, as in Example 3 from the first session:

The therapist makes the request, the client performs, the therapist evaluates the performance. This predictable structure, along with the routinized phrase (“Show me …”), serves as a resource to the participants allowing them to stay on track efficiently, maintain the flow, and complete the work of instruction in an organized fashion.

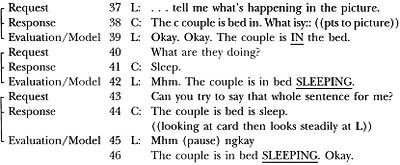

During the second session, this format is initiated and proceeds with each triad ending with an evaluation and model of the target sentence, followed by the next request.

Example 4

Throughout these sequences L and C fulfill the expected therapy discourse format. Talk during tasks is directed toward fulfilling the current RRE sequence relative to the specific stimulus item chosen by the therapist. Side sequences are initiated only to repair misunderstandings or assist the client in obtaining the correct response. A topic change by the client or a client’s refusal to perform the task are not permitted within the context of therapy, and such behaviors are not observed in either session (until the argument ensues).

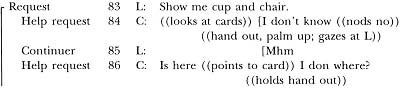

C is an active collaborator in the construction of this discourse pattern. While L presents the request portion of the RRE sequence, C attends carefully and gazes at L. As soon as L completes the instruction, C begins her designated, expected response. The give-and-take is orderly and swift. When C is unable to respond accurately, she signals a need for help (such as gazing steadily at L, verbally requesting help). The following sequence from the first session is an example:

Example 5

C recognizes that her job is to provide the correct answer. However, difficulty providing the correct answer is not unexpected. When C encounters difficulty, she solicits the help of L, who provides cues or prompts. Both parties participate in this enactment of the helper–helpee relationship in order to fulfill therapeutic goals. C accepts the subordinate position and signals her appreciation for the help with a polite “Thank you.” Once C performs the requested behavior, C looks up at L and awaits the evaluation phase of the adjacency triad. In order for this structure to proceed, both parties must accept that L is an expert equipped to help C, the incompetent speaker.

Thus, routine therapy interactions between C and L simultaneously manifest and construct the social roles as therapist and patient. These roles are reflected in the structure of the session and the talk-in-interaction. The norms of therapy conduct are created cooperatively. Here we see a typical example of resources jointly enacted by therapist and client to maintain therapist control, organize the session, and promote cooperation. The client not only adheres to the interactive routines, but looks to the therapist for completion of the adjacency triad. Within the therapeutic context both parties know their place and keep their place, consistent with their negotiated social roles.

CONFLICT WITHIN THE THERAPY ENCOUNTER

At times, however, there is the need or desire for a shift in a participant’s social role—even within the rigid structure of the therapeutic context. In such instances there is a dynamic interplay between the norms of therapy conduct, the expected social roles, the stability of established routines, and the competence required to shift role. This interplay can result in conflict between participants within the therapeutic encounter. The talk involved in negotiating the conflict can be examined, providing insight into these institutionalized routines, social roles, and interactive competencies. Such was the case with L and C. In the second therapy session, which is detailed in the remainder of this chapter, C attempts to shift her social role from that of “a patient in need of help” to the role of “a consumer concerned about the therapy services.” That is, within the session, C begins to allude to her lack of progress and the repetitious therapy task. This requires a shift in C’s social role, but it is a shift that apparently is not accepted by L. Consequently a conflict arises. This conflict is examined to determine how the interaction is structured and advanced, to determine what conflict reveals about the power of talk-in-interaction, and to highlight the communicative competency exhibited by C.

The session containing the conflict of interest begins characteristically with an opening phase and introduction to the task involving joint focus, establishment of common ground by referring to previous tasks and sessions, and requests to perform. The task consists of Response Elaboration Therapy (Kearns, 1985), in which C is asked to verbally describe a picture, progressively expand her descriptions, and write the picture description. This task had been repeated in several past sessions using the same set of pictures.

Signaling the Onset of Conflict via Affective Shift

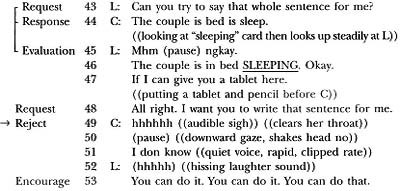

As the therapy activity unfolds, both L and C adhere to the expected structure and therapy proceeds as usual. Then the trouble begins. The first hint of conflict is apparent in Example 6, line 49, when C displays an affective shift that marks the onset of the conflict between the therapist and client.

At this juncture L makes a request (line 48) and C appears to express unwillingness to respond to the request (line 49). The contextualization cues offered by C in line 49 are highly uncharacteristic of her usual response to a request. Unlike prior responses to requests, C does not immediately perform the task nor does she employ the customary signals requesting help. In fact, C shifts her gaze away from L, sighs, and shakes her head as though she is rejecting the request itself.

L recognizes the failure to perform as evidenced by her laugh (line 52) and encouragement to C to perform the task (line 53). It appears that L interprets C’s response as difficulty due to language deficit—a lack of competence to perform the task. This is gleaned from L’s prompt to perform: “You can do it.” L invokes her expert authority to persuade C that the task is within her ability in spite of the language deficit. In other words, L interprets C’s uncharacteristic rejection by employing her stable therapeutic expectation and her interpretation of C’s actions as an “incompetent patient.” In effect, these assumptions construct L’s interpretive framework.

Within this framework, L’s interpretation bears on the local context (a focus on the task) and L’s belief that C would willingly perform the task if able (the social contract). Thus, C’s rejection is interpreted by L within the context of therapy discourse structure and the roles of therapist–patient. Given this interpretation, one would expect that the expert’s encouragement would help C perform the task—obtain the correct answer—then L and C would resume the routine. In fact, the encouragement does result in C’s performance of the task as follows:

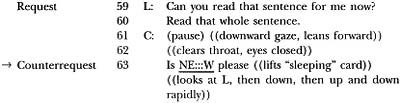

Escalation of Affective Signaling

In Example 7, line 54, C again registers discontent. Although C writes the sentence as requested, she sighs loudly, frowns, audibly drops the pencil, and shoves the completed work at L in an obvious display of dissatisfaction and anger. C’s affect is incongruent with her cooperative performance. However, L ostensibly directs her next turn (line 58) to the cooperative task performance rather than the negative affect by maintaining the request-response-evaluation (RRE) sequence with “Good. Very good.” Although L maintains the integrity of the therapy RRE structure rather than diverge to address C’s affect, it is interesting that L’s evaluation of C’s begrudging performance is considerably more positive than her prior evaluations. L switches from “Okay” and “Mhm” to “Good. Very good.” Possibly this special reward serves several purposes—to reinforce a correct sentence, to reward C’s return to appropriate therapy behavior (fulfilling a request), and to rebuild affective alignment, which has eroded with C’s anger display. L fulfills her role in maintaining the RRE therapy structure in spite of trouble brewing, and crafts her evaluation to insure continuation of this format.

As noted, L does not disrupt the RRE sequence to address C’s affective shift. Rather, she continues with the therapy structure by moving into another request sequence, as follows:

Example 8

Signaling Conflict via Rejection

Clearly, C has not conformed to the expected RRE adjacency triad. Rather, C nonverbally rejects L’s request and offers a counter request (lines 61–63). C’s intent to request is apparent from her intonation and politeness tag “please.” Although retrospectively it is apparent that C is requesting a new task or new picture cards, L expresses confusion over C’s behavior and responds to C’s request with a long repair sequence, which in effect derails C’s request for a new task.

Example 9

| 64 | L:h | New? [What ya mean? |

| 65 | C: | [Yeah, plea::se ((tense voice)) |

| 66 | I don know ((nods “no” rapidly)) | |

| 67 | is is alu ((gestures stop)) | |

| 68 | ((writes “enough”))((loudly drops pencil)) | |

| 69 | PLEA:::SE | |

| 70 | L: | Enough?= |

| 71 | C: | Yeah. |

| 72 | L: | =What ya mean? |

| 73 | C: | Isy ((pointing to “sleeping” card)) |

| 74 | is is is good ((speaks rapidly, points to tablet then to card)) | |

| 75 | is NE:::W ((points to L)) | |

| 76 | L: | What’s new? |

| 77 | What ya [mean it’s new? | |

| 78 | C: | [Is is too |

| ((leans forward and sweeps hand across cards on L’s side of table)) | ||

| 79 | L: | You want anoth[er one? |

| 80 | C: | [Yeah, plea::se. |

After this extended repair sequence, L finally interprets C’s request as a request for a “new card.” However, rather than immediately fulfill C’s request, L repeats the general instructions characteristic of task introductions.

| 81 | L: | What I’d like you to do is go through |

| 82 | and [read it after you’ve written it. |

Thus, L refuses to fulfill C’s request. Instead she appears to interpret C’s utterance as a symptom of misunderstanding of the task requirements, and reverts to the “introducing the task” structure in an attempt to restart the therapy routine and re-enter the RRE sequence. This results in an affective display by C, as follows:

| 83 | C: | [I know (pause) I don kno::w ((gaze down)) |

| 84 | 0::h o:h no:::: ((grabs head)) | |

| 85 | L: | Too frustrating today? |

| 86 | C: | Yeah— ((clipped, terse)) |

| 87 | L: | Okay. The couple is sleeping in bed. |

| 88 | That was good. Perfect sentence. | |

| 89 | Nothin’ wrong with it ((singsong intonation)) | |

| 90 | Awright, let’s look at this one. | |

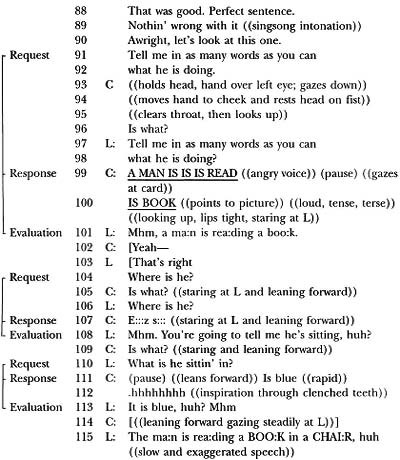

| 91 | Tell me in as many words as you can | |

| 92 | what he is doing. |

In line 85 L again interprets C’s affect as anger and frustration with inability to perform—aphasic incompetence (as in Example 6, line 53). In contrast, there is a decidedly sarcastic tone in C’s response of “yeah” to L’s query “Too frustrating today?” (lines 85, 86). Clearly, L refers to frustration performing the task due to aphasia. C refers to frustration with L’s failure to acknowledge C’s request for a new task; frustration over not being heard as a “competent consumer.” The misunderstanding reflects two different role orientations. L continues to cast C as the frustrated and incompetent “aphasic patient.” C is now casting herself as the “competent consumer” who wants to move on to new material in treatment.

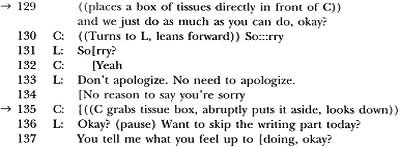

After L expresses sympathy with C’s frustration, the therapist moves to preserve the outline of the RRE sequence in spite of C’s failure to perform. In effect, L makes a request (Example 10, line 81) that C rejects (Example 11, lines 83, 84); then L evaluates (Example 11, lines 87–89) as though C has performed the task, filling the last slot of the three-part sequence and providing a structural entree to continue the session. In Example 12 (a reformat of Examples 10 and 11), the attempt to preserve the RRE structure can be seen.

![]()

L maintains the RRE sequence by evaluating a “ghost” response; that is, L continues as though the patient has fulfilled the request. Once the evaluation slot is filled with a positive evaluation (lines 87–89), the therapist is free to proceed to the next therapy item (line 90). Again L has used a routinized structure to get treatment back on track and disregard C’s attempt to derail the task. The structure of talk repositions C into the patient role and reinforces the therapy contract.

From the first sign of trouble in Example 6, L has interpreted the interaction in terms of C’s frustration with performance of a particular therapy item. Initially (Example 6, line 53), L interprets C’s negative affect as difficulty performing the task—an expected symptom of incompetence. Later, L repeats the general instructions (Example 10, line 81), suggesting that C has failed to understand the task overall—a symptom of incompetence. Finally, in Example 11, line 85, L again interprets C’s behavior as a display of frustration in performing the task—a symptom of incompetence. Throughout the interaction L responds to C within the confines of therapeutic role. That is, L is the expert who makes requests; C is the patient who performs requests. If C does not perform, it is due to aphasia (incompetence). L adopts a discourse structure that maintains L’s position in control. Thus, L stays firmly in role and responds to C within the narrow role definitions of therapist and patient.

C, on the other hand, has clearly attempted to extricate herself from addressing the therapy task and is, in fact, questioning L’s control and L’s treatment plan. C adopts the role of a consumer of services who has evaluated the service and found it deficient. She wants a new task and attempts to communicate this request to L.

Maintaining the Therapeutic Focus

Over the next several turns C and L negotiate to maintain the interaction and to avoid conflict. C complies with L’s requests, although C’s affect continues to reflect anger and frustration and she derails the flow of the session with repeated requests for clarification. C appears to struggle not to completely reject her role as patient; however, the session does not proceed as smoothly and seamlessly as usual.

Example 13

C complies with requests, but her performance is characterized by clarification requests and incomplete responses. L appears to interpret this behavior as difficulty performing the task, and adjusts the discourse structure to facilitate C’s task performance. The session continues in this manner with L simplifying requests and accepting approximate responses in deference to C’s frustration. This therapist’s behavior is entirely consistent with the recommendation of aphasia therapy texts to simplify tasks to promote successful performance and reduce frustration (e.g., Davis, 1993). Thus, L continues to judge C’s affect as evidence of “deficit frustration” or incompetence, and consequently reduces the demands.

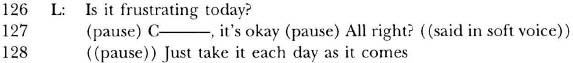

Shifting the Focus From Therapy to Conflict

Up until this point in the interaction, both C and L have maintained their focus on therapy activities. As seen in Example 14, however, the precariously maintained RRE sequence entirely degenerates when C begins to cry (line 125).

| 124 | L: | Is that what you were going to tell me? |

| 125 | C: | I don know is is |

| ((crying, looking down at lap, body turned to side)) | ||

| 126 | L: | Is it frustrating today? |

| 127 | (pause) C———, it’s okay (pause) All right? ((said in soft voice)) | |

| 128 | ((pause)) Just take it each day as it comes | |

| 129 | ((places a box of tissues directly in front of C)) | |

| and we just do as much as you can do, okay? |

L continues to craft utterances suggesting that the problem with the session is C’s incompetence (line 126). L interprets the interaction within their social contract as therapist and patient, without recognizing that C has attempted to shift out of this role. L reinforces her authoritarian role by giving C permission to be frustrated (“it’s okay”) and offering alternatives (“we just do as much as you can do”). Although L is genuinely attempting to console and encourage C, in effect, L is addressing her as an incompetent person. L maintains control of the session and fails to hear the voice of the competent consumer.

At this time C appears to collaborate with L’s participation frame in a variety of ways. She has continued to fulfill requests (lines 99, 107, 111) suggesting that “therapy continues.” Filling the response slots constitutes an implicit acknowledgment of her patient role. After starting to cry, C apologizes for her behavior in a subservient manner; this bolsters L’s power position. Thus, C’s discourse exposes C’s difficulty shifting out of her dependent patient role.

C’s anger is not appeased by L’s “pardon” of her behavior in line 127. Instead the conflict generalizes beyond the therapy task. Note in the following sequence that L has provided a box of tissue (line 129); C abruptly rejects the offer of tissue by roughly returning the box to its original position (line 135). This nonverbal power struggle parallels the verbal argument.

Example 15

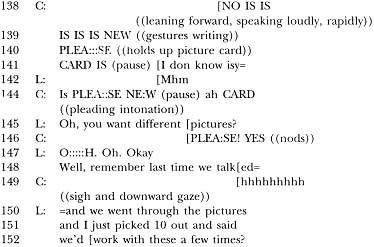

Having nonverbally demonstrated that the conflict continues, C makes another request for a new task as follows:

Example 16

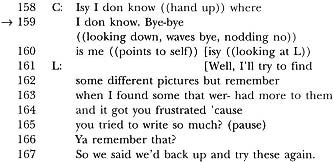

L recognizes C’s request for new pictures; however, L defends her continued use of this task (lines 148, 150). In effect, L’s utterance serves as an implicit rejection of C’s request since it is an accounting of why the task is appropriate. Through this implicit rejection, L is acting to defuse C’s concerns and requests. Consequently, C escalates her demands and meets this rejection with a threat to leave (I don know. Bye bye) in the following sequence (line 159):

Example 17

In response to C’s threat, L makes an offer to find different pictures (“Well, I’ll try. …”). It is remarkable that at this point in the conflict L continues to struggle for control. Her use of the marker “Well” suggests continued disagreement with C’s request and potential noncompliance with the request (Schiffrin, 1987). This is reinforced by her use of the qualifier “I’ll try,” suggesting that she might not find different pictures. L then provides another accounting for the task based on C’s history of difficulty performing other, more difficult tasks (lines 162–167). This accounting also reinforces the patient role by reminding C of her past incompetence.

In response to L’s defense of the task, C defends her request by repeating her threat to leave (“Is bye bye”) and providing an explanation of her motive for the request—financial concerns (line 170: “Is money”). Apparently, C is referring to her limited funds; as a consumer she no doubt wants to make “every minute count.” Thus, C appears to be arguing that doing the same task repeatedly is not cost effective.

Example 18

| 168 | C: | ((looking down, looks up and then down)) |

| 169 | Isy, I don know isy. Is bye-bye | |

| ((waves with rapid expansive gesture)) | ||

| 170 | Is MONEY ISY ((gestures grasping money to self)) | |

| 171 | BYE-BYE ((waves)) | |

| 172 | L: | About money? |

| 173 | C: | YEAH::: IS ME. PLEA::SE |

| 174 | IS NEW ((leans forward; stares at L)) | |

| 175 | L: | OKAY, OKAY. IT’S AWRIGHT! |

| 176 | I’ll find some new ones. | |

| 177 | Can we use these today then | |

| 178 | [since I haven’t picked any new ones out? |

At this point the conflict is clearly the focus of the interaction. For most of the session, both parties have attempted to maintain their roles and avoid entirely shattering the structure of therapy. L has repeatedly pulled the interaction back into the RRE framework of a therapy interaction. She has responded to C based on an expectation of patient behavior and patient frustration, and has altered the task difficulty to reduce C’s frustration with her distressing deficit. C’s assertion of herself as “consumer” was contaminated by continued fulfillment of L’s expectations (performing requests). Thus, both L and C continued to fulfill the social contract between therapist and patient until the conflict became the central focus of the interaction. Once the argument became the central focus, the routines of therapy were abandoned and a power struggle ensued. C was furious that her consumer request went unheeded. L was confused and distraught that C’s aphasic frustration could not be mitigated through therapeutic control. The struggle continued until C finally walked out of treatment.

DISCUSSION

The Complexity of Discourse

Conversational analysis of therapy sessions between L and C revealed remarkable interactive complexity and structure hidden beneath what appeared to be simple activities.

Routine Therapy Discourse. The structure of therapy discourse proved a powerful resource for constructing and maintaining routines of therapy and social roles of competent expert and incompetent patient. For example, the adjacency triad of request-response-evaluation (RRE) was a key feature marking the interaction as a therapy routine. Both L and C knew their part in the RRE sequence and constructed a seamless give-and-take characteristic of an efficient therapy session. As long as this structure was maintained, therapy proceeded and associated social roles were enacted. When trouble was encountered, the therapist played her part flawlessly by employing methods of modifying the talk to insure that C filled the middle slot of the RRE sequence. L simplified requests, rewarded incomplete responses, and even rewarded a “ghost” response in order to continue therapy. Therapy discourse constituted a recognizable, routinized global structure, which both participants enacted in order to achieve remedial goals. Therapy discourse shaped, and was shaped by, the social roles played by each participant.

The Discourse of Argument. Once the routine structure of therapy dissolved, the argument became the discourse focus and the competing roles of competent consumer and incompetent aphasic became readily visible. C’s rejection of the RRE triad and replacement of it with the nontherapy adjacency pair of “request–reject” resulted in a shift into conflict. The argument constituted a negotiation in which the therapist attempted to get back into therapy routines, while C attempted to make her request understood. Both parties participated in the give-and-take of the conflict with competing adjacency pairs of “therapist request–client rejection” and “client request–therapist rejection.” Each participant employed discourse strategies typical of “normal” arguments in an effort to get her way. For example, both used “accountings” for rejecting the other’s request and reasons why their request should be honored. In Example 19, lines 162–167, L provides a reason to continue with the current task:

| 161 | L: | [Well, I’ll try to find |

| 162 | some different pictures but remember | |

| 163 | when I found some that wer- had more to them | |

| 164 | and it got you frustrated ‘cause | |

| 165 | you tried to write so much? (pause) | |

| 166 | Ya remember that? | |

| 167 | So we said we’d back up and try these again. |

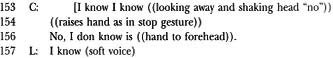

C accounts for her request based on finances (“Is money”) and adds a threat to leave if her request is not fulfilled:

Example 20

| 169 | C: | Isy, I don know isy. Is bye-bye |

| ((waves with rapid expansive gesture)) | ||

| 170 | Is MONEY ISY ((gestures grasping money to self)) | |

| 171 | BYE-BYE ((waves)) |

Another characteristic of nontherapy argument found in L and C’s interaction is the tendency for conflict to override the original argument topic. Thus, the conflict generalizes from the topic of new pictures to C’s rejection of the tissue offer (lines 129–135) and later disagreement regarding the video camera (see Appendix, lines 181–199). Thus, in the “tissue box interaction” C abruptly pushes the box aside, physically demonstrating the power struggle. L is acting as “helper” providing tissues, C rejects help and acts independently. Similarly, at the end of the interaction, L and C “argue” about the best method to turn off the video camera. In other words, the power struggle born within the treatment task overflows into other aspects of the relationship. C no longer plays the role of patient; L continues to treat C as a patient. This negotiation of power and identity across several topic areas is a typical characteristic of argument (Goodwin & Goodwin, 1990; Varenne, 1987).

An additional characteristic of the argument session, which is consistent with nontherapy discourse, is the preference for agreement and avoidance of conflict (Brown & Levinson, 1978; Pomerantz, 1984; Sacks, 1987). This was apparent in the slow onset of the argument. Initially, C uses affective signals to alert the therapist to her dissatisfaction. In effect, C’s early affective displays represent a slow leakage of her consumer role into her role as the patient. As typical of nonaphasic speakers, she avoids open disagreement and upsetting the power balance by delaying an overt demand for a new task—an overt and sudden shift of role. The affective signals identifying her as a “dissatisfied customer” might have been adequate to alert the therapist, if the therapist had not been biased by her own expectations. That is, the therapist expected negative affect to signal “frustration with aphasia” not “consumer dissatisfaction.” Thus, an agreeable solution was not negotiated despite C’s relatively subtle attempts to express her “consumer voice.”

The conflict between C and L constituted an orderly, though sometimes angry, give-and-take proceeding across 80 turns. Although C’s turns were characterized by telegraphic utterances, she employed legitimate speech acts and discourse devices to negotiate turn-taking and to construct meaning. Both C and L moved slowly into the argument as they initially made efforts to avoid disagreement and confrontation. Finally, the argument erupted, proved irreconcilable, and the interaction terminated.

Therapeutic Insights

This conversational analysis of therapeutic interaction provided two insights into the institution of therapy as experienced by L and C. First, their argument provided a window into the rigid social roles constituted by therapy and exposed routinized features of the institution of therapy that hinder the enactment of multiple social roles.

Second, the argument provided an excellent example of a language-disordered individual demonstrating remarkable interactive competence as she negotiated the talk to maintain a difficult interaction. Furthermore, the analysis demonstrates the “creation” of incompetence via expectation. That is, the therapist expected C to be incompetent, and interpreted the talk in light of this expectation. The expert failed to recognize the interactive competence of her client.

Argument as a Window to Social Role. The finding that argument provided a window into the rigid social roles associated with therapy is consistent with prior research demonstrating that arguments can effectively display social organization and reveal how participants situate themselves in particular types of social contracts (Goodwin & Goodwin, 1990; Maxwell, 1993). This is clearly apparent as this argument session demonstrates the strongly established social roles associated with the institution of aphasia therapy. The analyzed therapy session involved an unstated social contract, which cast the participants into designated roles as expert and patient. The argument exposed the conflicting roles as the participants struggled to negotiate an agreeable interaction. The implied social contract and resulting roles were visible in the discourse structure and content—the talk-in-interaction. In fact, the talk both created and was shaped by these roles.

The drive to maintain the social contract and avoid disagreement was very strong as evidenced in C’s initial vacillation between “performing” and “rejecting” requests, and L’s persistent adherence to the RRE structure. The roles were rigidly wrought and interpretation of talk inconsistent with role expectations proved difficult—in fact, impossible. Thus, the rigid role casting prevented the participants from succeeding in communicating outside of therapeutic expectations. Ultimately, the interaction dissolved and the therapy relationship terminated.

Argument as a Window to Competence. Research has demonstrated that argument in human discourse is a highly complex and organized activity requiring “a process of very intricate coordination between the parties who are opposing each other” (Goodwin & Goodwin, 1990, p. 85; Grimshaw, 1990). Argument entails not only competition, but also cooperation (Schiffrin, 1990). There is a need to collaborate in order to follow some organized and agreed-on sequence that allows both parties to participate and proceed in an orderly, albeit conflicting, fashion (Goodwin & Goodwin, 1990; Schiffrin, 1990). The argument between L and C is an excellent example of an intricate and complex negotiation. From the beginning to the end of the session, L and C engage in an orderly give-and-take of talk. Early on, the discourse conforms to “therapy” routines. While C attempts to communicate her displeasure with the choice of task, this is initially accomplished through affective displays, but the structure of the session is preserved. As the conflict proceeds, C begins to disrupt the RRE routines by rejecting and derailing requests. These are legitimate discourse options available to participants in nontherapy discourse; thus, C uses her “discourse competence” to remove herself from the “therapy options” and perform options permitted to competent speakers. L attempts to keep C on track by reverting to routines of therapy and casting C as a “frustrated patient.”

Both L and C employ normal interactive resources for arguing. They take turns. They threaten. They defend. They raise their voices. Thus, C demonstrates her competence as a discourse partner. Not only has she expertly conformed to the institutionalized discourse routines of therapy, but she also demonstrates the capacity to shift successfully and easily into another discourse genre. In spite of this finely tuned negotiation demonstrating C’s competence as a communicator, C remains cast in the role of the incompetent patient. Which returns us to our first observation: The institution of therapy brought with it a fixed role for C—that of the incompetent patient. The rigid role masks C’s potential as a competent communicator and a competent consumer, able and willing to make decisions regarding her future.

Thus, the argument not only exposes the strong drive of both participants to maintain established therapeutic identities and shape talk to fulfill these roles, but it also reveals competence that has been masked by the institution of aphasia therapy. The therapist was “blind” to the fact that the difficulty encountered with the session was due to a competent human being struggling to extricate herself from a dependent social role. As in all conversation analysis, it is easy to be insightful retrospectively. The reader will appreciate that the transcribed argument, although taking pages to transcribe and analyze, occurred in a matter of minutes; the therapist did not have the luxury of deeply analyzing each utterance. As a caring person who genuinely wanted to improve C’s communication, she was surprised and bewildered by the conflict. We question the institution of traditional therapy, not the therapist. Panagos (1996) raised the possibility that structured therapy, with rigid role casting, can have undesirable side effects. We believe that these data provide an example of potential problems associated with institutionalized therapy routines: specifically, the failure to appreciate potential communicative competence in our clients, the undermining of a client’s communicative confidence, and the potential dissolution of therapeutic relationships. Even though routines of therapy have evolved in order to support the therapist’s position as a mediator and facilitator, these routines can create an atmosphere that fails to foster a client’s competence, confidence, and well-being.

Analysis of this aphasia therapy session raises interesting questions about traditional therapy as an institution. Does the institution of therapy over-enforce nonegalitarian role casting as a means to mediate communication change? Does rigid role casting deprive our clients of an opportunity to successfully experience a variety of communicative roles? Does the institution of therapy prevent us from viewing the interactive competence of individuals cast as “disordered”? What is the effect on communicative competence of such practices?

Further research is needed on the discourse of traditional aphasia therapy. In addition, study of alternative aphasia interventions could provide important insights. Alternatives to traditional aphasia therapy (such as conversation groups focused on social interaction) have been suggested in order to build increased social participation and foster communitive confidence (e.g., Elman & Bernstein-Ellis, 1996; Kagan & Gailey, 1993; Simmons-Mackie, 1997). Research comparing the interactive dynamics of these interventions to traditional therapy discourse might reveal methods of mediating communication change while, at the same time, reinforcing and expanding a variety of social roles. Perhaps further study of the interactions between therapists and clients can increase our understanding of this complex but extremely important aspect of therapeutic effectiveness and help us hear the “other voices” of our clients.

Argument Session Transcript

Setting: Aphasia therapy session between L (speech-language pathologist) and C (client). L and C are seated across from each other at a table in a therapy room.

REFERENCES

Bobkoff, K. (1982). Analysis of the verbal and nonverbal components of clinician-client interaction. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Kent State University, OH.

Brookshire, R. H. (1992). An introduction to neurogenic communication disorders. St. Louis, MO: Mosby.

Brown, P., & Levinson, S. (1978). Universals in language usage: Politeness phenomena. In E. Goody (Ed.), Questions and politeness (pp. 58–189). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Button, J., & Lee, J. (Eds.) (1987). Talk and social organization. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters, Ltd.

Damico, J. S., & Damico, S. K. (1997). The establishment of a dominant interpretive framework in language intervention. Language, Speech and Hearing Services in the Schools, 28, 288–296.

Damico, J., & Simmons-Mackie, N. (1996). Maintaining impairment in aphasia therapy: The co-construction of deficit via talk-in-interaction. Paper presented at the International Pragmatics Association Conference, Mexico City.

Davis, G. A. (1993). A survey of adult aphasia and related language disorders. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Duchan, J. (1993). The IRE structure as viewed ethnographically. Presentation at the First International Round Table of Ethnography and Communication Disorders, Urbana, IL.

Elman, R., & Bernstein-Ellis, E. (1996). Effectiveness of group communication treatment for individuals with chronic aphasia. Presentation at the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Annual Convention, Seattle, WA.

Goodwin, C., & Goodwin, M. (1990). Interstitial argument. In A. Grimshaw (Ed.), Conflict talk (pp. 85–117). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Goodwin, C., & Heritage, J. (1990). Conversation analysis. Annual Review of Anthropology, 19, 283–307.

Grimshaw, A. (Ed.). (1990). Conflict talk. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Kagan, A., & Gailey, G. (1993). Functional is not enough: Training conversational partners for aphasic adults. In A. Holland & M. Forbes (Eds.), Aphasia treatment: World perspectives (pp. 199–226). San Diego, CA: Singular.

Kearns, K. (1985). Response Elaboration Training for patient initiated utterances. In R. Brookshire (Ed.), Clinical aphasiology conference proceedings (pp. 196–204). Minneapolis, MN: BRK Publishers.

Klippi, A. (1991). Conversational dynamics between aphasics. Aphasiology, 5, 373–378.

Kovarsky, D. (1989a). An ethnography of communication in child language therapy. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Texas, Austin.

Kovarsky, D. (1989b). On the occurrence of okay in therapy. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 5(2), 137–145.

Kovarsky, D. (1990). Discourse markers in adult-controlled therapy: Implications for child centered intervention. Journal of Childhood Communication Disorders, 13(1), 29–41.

Kovarsky, D., & Maxwell, M. (1992). Ethnography and the clinical setting: Communicative expectancies in clinical discourse. Topics in Language Disorders, 12(3), 76–84.

Maxwell, M. (1993). Conflict talk in a professional meeting. In D. Kovarsky, M. Maxwell, & J. Damico (Eds.), Language interaction in clinical and educational settings (pp. 68–91). Rockville, MD: American Speech-Language-Hearing Association.

McTear, M. F., & King, F. (1991). Miscommunication in clinical contexts: The speech therapy interview. In N. Copeland, H. Giles, & J. M. Weimann (Eds.), Miscommunication and problematic talk (pp. 195–214). London: Sage.

Mehan, H. (1979). Learning lessons. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Panagos, J. (1996). Speech therapy discourse: The input to learning. In M. Smith & J. Damico (Eds.), Childhood language disorders (pp. 41–63). New York: Thieme, Inc.

Pomerantz, A. (1984). Agreeing and disagreeing with assessments: Some features of preferred/dispreferred turn shapes. In J. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eels.), Structures of social action: Studies in conversation analysis (pp. 57–101). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Porch, B. (1981). The Porch index of communicative ability. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Porch, B. (1994). Treatment of aphasia subsequent to the Porch index of communicative ability. In R. Chapey (Ed.), Language intervention strategies in adult aphasia (pp. 178–183). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

Psathas, G. (1995). Conversation analysis: The study of talk-in-interaction. London: Sage.

Ripich, D. N. (1982). Children’s perceptions of speech therapy lessons: A sociolinguistic analysis of role-play discourse. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Kent State University, OH.

Ripich, D. N., Hambrecht, G., Panagos, J. M., & Prelock, P. A. (1984). An analysis of articulation and language discourse patterns. Journal of Childhood Communication Disonkrs, 7(2), 17–26.

Sacks, H. (1987). On the preferences for agreement and contiguity in sequences in conversation. In J. Button & J. Lee (Eds.), Talk and social organization (pp. 152–205). Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters, Ltd.

Sacks, H., Schegloff, E., & Jefferson, G. (1974). A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language, 50, 696–735.

Schiffrin, D. (1987). Discourse markers. London: Cambridge University Press.

Schiffrin, D. (1990). The management of a cooperative self during argument: The role of opinions and stories. In A. Grimshaw (Ed.), Conflict talk (pp. 241–259). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Schiffrin, D. (1994). Approaches to discourse. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Silvast, M. (1991). Aphasia therapy dialogues. Aphasiology, 5, 383–390.

Simmons, N. (1993). An ethnographic investigation of compensatory strategies in aphasia. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA.

Simmons-Mackie, N. (1997). Adult aphasia: Alternatives to traditional approaches. Presentation at the Southwest Conference on Communicative Disorders. Albuquerque, NM.

Simmons-Mackie, N., Damico, J., & Nelson, H. (1995) Interactional dynamics in aphasia therapy. Presentation at the Clinical Aphasiology Conference, Sunriver, OR.

Varenne, H. (1987). Analytic ambiguities in the communication of familial power. In L. Kedor (Ed.), Power through discourse (pp. 129–152). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Wilcox, J., & Davis, G. A. (1977). Speech act analysis of aphasic communication in individual and group settings. In R. Brookshire (Ed.), Clinical aphasiology conference proceedings (pp. 166–174). Minneapolis, MN: BRK Publishers.