11

Understanding Inclusion: Resource Material for Teacher Educators

Anupam Ahuja and Els Heijnen

Inclusion is one of the major challenges faced by education systems around the world. The question of how schools can include all children from the communities they serve and enable them both to participate fully and to achieve well is a pressing concern for teachers and others working with issues of equity and social justice in contemporary and future society.

Education systems and school development is, now, increasingly focused on the right to Education for All (EFA) in one national, mainstream system. In describing its vision for EFA, the Dakar World Education Forum (April 2000) stated clearly that Inclusive Education (IE) is vital if this goal is to be achieved. As a result, many countries, including India, are moving towards developing mainstream IE policies and practices, while taking responsibility for all children!

“The key challenge is to ensure that the broad vision of Education for All as an inclusive concept is reflected in national government and funding agencies’ policies.…”

From: Dakar Framework for Action (2000) — Para 19

What is “Inclusive”?

- Including ALL children who are left out or excluded from school:

- children with disability;

- children who do not speak the language of the classroom;

- children who are at risk of dropping out because they are sick, hungry, or not achieving well;

- girls and boys who should be in school but are not, (e.g. children who work at home, in the fields or who have paying jobs to help their families survive) and

- children who may be enrolled in school but may feel excluded from learning in the classroom (e.g. the ones who sit at the back of the room, and who may soon leave the classroom altogether (dropout) because they are not from the same community

We are responsible for creating a learning environment where ALL children can learn and feel included in the learning community within and outside our classrooms and schools.

The Concept of Inclusion and IE

Inclusion or IE is an integral part of Education for All. There can be no quality education without being inclusive and responsive to learning diversity and other aspects of difference. IE is about building a more just society and ensuring the right to education of all learners, regardless of their individual characteristics or difficulties. This means that IE initiatives have a particular focus on those groups that have, traditionally, been excluded from equal education opportunities. This can only happen if public mainstream schools become more inclusive or, in other words, they become more capable of educating ALL children in their communities. Part of the process, towards IE requires a critical analysis as to why the mainstream system is not successful in providing good quality education for all. It, also, asks for identification of existing resources and innovative practices in local contexts, and examining barriers to participation and learning. Improving the mainstream system, from an inclusive perspective, benefits all children.

The barriers, which different groups of learners encounter, cannot be overcome by developing parallel systems and separate schools or classrooms. However, teachers in mainstream classrooms may need additional professional support to give all children the individual learning support they need, because meeting one child’s needs at the expense of another cannot be a way forward.

The education system has to become responsive to diversity. Teachers need to learn to look at diversity as something positive, which adds value to the education of all children. Local community schools need to be schools for all and no child should be excluded. Effective teaching research has shown that good teaching is good teaching for all children, irrespective of individual differences and that improved teacher training and ongoing professional teacher support may be one of the most important strategies to improve quality education for all.

Inclusive practice varies from context to context and is closely linked to the possibilities and challenges within the education system and the community and to the various barriers associated with the teaching and learning processes.

Developing Inclusive Education

An inclusive school is not simply one, which educates children with disabilities; rather inclusive education is about reducing all barriers to learning and developing ordinary schools, which are capable of meeting the needs of all learners. The development of an IE system means that we have to change the focus of our work so that we can support children in their ordinary schools and maintain them in the communities.

It is important to keep in mind that barriers can be seen:

- within the learner,

- within the centre of learning,

- within the teaching,

- within the family,

- within the education system and

- within social, political and economic contexts.

These barriers can be conceptual, attitudinal, financial, epistemological, structural, temporal and professional. Such barriers become visible when learners do not enrol, do not participate adequately learn or drop out of systems. The question that challenges us all is: How we can plan and implement sustainable educational provision responding to individual circumstances in a holistic manner for ALL children? Can developing inclusive child friendly settings help?

As per Constitutional, legal provisions and/or existing policies schools are open for ‘All Children’ in most of the countries but in practice many children continue to

- The excluded children:

- Physically and intellectually challenged children

- Girls and boys who should be in school but are not, (e.g. children who work at home, in the fields or who have paying jobs to help their families survive)

- Children in living in poverty/slums,

- Children belonging to Ethnic, Linguistic and Religious minorities

- Children affected by hunger, malnourishment, HIV etc.

- Abused children

- Children affected by natural calamities like cyclones, river erosion

- Children in jail or correction centre

- Child victims of trafficking, drug addiction

AND ALSO

- Children who may be enrolled in school but may feel excluded from learning in the classroom e.g. the ones who sit at the back of the room, and who may soon leave the classroom altogether (dropout) because they are not from the same community

- and many others

Exclusion has often a social, financial, ethnic and lingual base

In this chapter, we help teacher educators, such as you, understand and then, discuss the fundamentals of inclusive education with pre-service and in-service teachers. We will clarify the concept of inclusive education and take a close look at how inclusive child friendly schools can be developed. We, also, hope that you along with your students will find the suggested list of readings and website links useful.

What is Inclusive Education?

INCLUSIVE EDUCATION-COMMON BELIEFS

- All children can learn

- All children are different

- Difference can and should be valued

- Learning is enhanced through cooperation with teachers, parents and the community.

- Societies are involved in creating difference

- We all belong and have a role in society

Inclusion is not just an educational philosophy but, more importantly, a process towards the practical changes that must be brought about, in order to help all children learn to their full potential, while recognizing that all children are different and have different individual learning needs and learning speeds, rather than ‘special’ needs. Homogenous classrooms do not exist. The shift towards inclusive thinking and planning will not merely benefit the children we often single out and label as ‘children with special needs’, but it will benefit all children, all teachers, all parents and all headmasters. IE is governed by some common beliefs. In defining inclusion, it is important to highlight the following elements:

| Inclusion IS about: | Inclusion IS NOT about: |

|---|---|

| • Welcoming diversity. | • Reforms of special education alone, but reform of both the formal and non-formal education systems. |

| • Benefits for all learners, not only those who have been previously marginalized or excluded. | • Responding only to diversity, but, also, improving the quality of education of all learners. |

| • Children already in school may feel excluded. | • Special schools, but more about individual support to students who need such things within the regular education system. |

| • Meeting the needs of children with disabilities. | |

| • Providing equal access to education and becoming more flexible and adaptive for certain children, without excluding them. | • Meeting one child’s needs at the expense of another child. |

Source: Adapted from UNESCO (2005). Guidelines for Inclusion: Ensuring Access to Education for All, p. 15, Paris: UNESCO.

Inclusive Education: Some Key Issues

To develop our understanding further, let us focus our attention on some key issues related to IE.

- IE is based on the belief that the right to education is a basic human right for all children and is the foundation for social justice. All children, whatever their difference, have a right to belong to mainstream society, to mainstream development and, therefore, to mainstream education. Though there is a special focus on learners vulnerable to marginalization and exclusion, IE increases the effectiveness of the system in responding to all learners!

- IE is consistent with the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) — ratified by most countries, including India and, thus, legally binding. IE is based on a rights and responsibility analysis showing that national education systems and mainstream schools are responsible for all children.

- IE takes the Education for All (EFA) agenda forward, by finding ways of enabling schools to serve all children in their communities, as part of a national education system.

- IE is about transforming mainstream systems (policies and practices) into more responsive systems and is, as such, concerned with all learners — providing equal opportunities in access, participation and learning.

- IE recognizes that every child has unique characteristics, interests, abilities and learning needs and, therefore, if the right to education is to mean anything, systems must be designed and programmes implemented to take into account the wide diversity of these characteristics and needs (e.g. children living in poverty, ethnic, linguistic or cultural minorities, children with disabilities, children from remote or nomadic populations, children of migrant workers).

- IE seeks to understand all barriers to access and learn and recognizes that many children may find learning difficult in ordinary schools as they are currently constituted. Repetition rates and poor learning achievements are importantly linked to what and how teachers teach and interact with learners. Children may find the curriculum uninspiring and irrelevant or they may have problems to understand the language of instruction.

- IE recognizes that mainstream education needs to accommodate different styles and rates of learning, while ensuring quality education to all children through appropriate and differentiated curricula, classroom organizational arrangements and flexible teaching strategies.

- IE is about transforming education focusing on (a) effective teacher education, (b) respecting and responding to diversity, (c) appropriate teaching aids and equipment, (d) professionally supported schools and teachers and (f) active involvement of parents and communities.

Why the Shift to a More Inclusive Ideology?

There have been a number of reasons for a shift to a more right-based ideology — some based on children’s rights and others based on lessons learned from providing services for children with disabilities or ‘special needs’.

We now provide you with a historical perspective of the origins of inclusion and describe the shift from integration towards inclusion. We will dwell further on how IE is based on a human rights approach and how it relates to quality.

IE in India, like elsewhere, is seen by many as a way to provide education for children with disabilities. However, as highlighted earlier, IE is not a special approach that shows us how some learners, such as students with disabilities, can be integrated in regular schools, but it looks into how mainstream systems can be transformed in order to respond to learners’ difference and diversity in a constructive and positive way — which includes, but is not limited to children with disabilities.

Historically, the policy of inclusion has its roots in the education of children with disabilities. Up to the 1970s, it was a normal procedure to place such children in special schools or units, which, often, resulted in exclusion from the culture, curriculum and community of local schools, as well as, mainstream society.

In the 1980s, ‘integration’ took over as the dominant model for educational placement. This model emphasized children’s ‘special needs’ and led to the development and use of individual lesson plans for children who were integrated in mainstream schools. Integration means placing students with mild to moderate impairments in classrooms with their peers without disabilities. Integration implies that you think about in what school or classroom a child would be placed if he or she would not have a disability. It, often, happens in integrated schools/classrooms that children only follow the lessons that they are perceived to be able to follow according to the teacher, and for many academic subjects, these children may receive alternative lessons or remedial teaching in a separate classroom — segregated from their peers. Integrated placement is not synonymous to instructional and social integration, because this depends on the support that is given in school (and the wider community).

Concerns about educational outcomes, costs, societal inequalities and moral imperatives prompted a change of attitude and the adoption of inclusion as a model with inspiration from the Salamanca Statement (1994). The inclusive model is now widely accepted and considered the most effective approach to education for all:

Regular schools with this inclusive orientation are the most effective means of combating discriminatory attitudes, creating welcoming communities, building on an inclusive society and achieving education for all; moreover, they provide an effective education to the majority of children and improve the efficiency and ultimately the cost effectiveness of the entire education system

(Centre for Studies in Inclusive Education, CSIE, Bristol, 1995)

Inclusion is a social and educational philosophy. Those who believe in inclusion believe in social justice, because all people are unique and all should be considered valuable members of society. In education, this means that all children, irrespective of their abilities or disabilities, socioeconomic background, ethnic, language or cultural background, religion or gender go together to the same community school.

Inclusive education

Inclusive education is the process of addressing learners needs within the ‘mainstream’ school, using all available resources to create opportunities to learn in preparing them for life. The emphasis is on reviewing schools and systems and changing them rather than trying to change students.

Source: Stubbs, S (2002 Inclusive Education: Where there are few resources; The Atlas Alliance, in cooperation with NAD

The inclusive philosophy is about: belonging to, contributing to a (school) community and about being respected for who and what you are. The opposite is exclusion, which conveys a sense of rejection, inferiority and powerlessness, and, often, leads to frustration and resentment.

Inclusion and IE do not look at whether or not children are able to follow the mainstream education programme, but at teachers and schools that can adapt educational programmes to individual needs. Central to the programme of IE is the belief that education makes a powerful contribution to the social construction of inclusive communities and an inclusive society. IE is concerned with children’s rights to access and participation, as well as, equal opportunities to engage in lifelong learning and employment. The concept of inclusion is closely related to the concept of child-friendly schools, a concept based on the CRC, also ratified by the Government of India.

Inclusive Education (IE) defined: IE is an approach to improve the education system by limiting and removing barriers to learning and acknowledging individual children’s needs and potential. The goal of this approach is to make a significant impact on the educational opportunities and outcomes of (1) those who attend school, but who, for different reasons, do not achieve adequately and (2) those who are not attending mainstream school, but who could attend if families, communities, schools and education systems were more responsive to their needs and rights.

In our country, there are existing strengths for prompting inclusive practice and these can, primarily, be summarized as:

- Societies are inclusive.

- Education is defined in a larger context.

- Innovations stem from a deep respect for education.

- Initiatives exist at the community level.

- The context, in particular the rural context, is not hindered by a legacy of segregation.

- Community solidarity exists.

- Expertise in utilizing resources has developed.

- ‘Casual inclusion’ is seen in practice.

The development of IE involves:

- Awareness raising and, often, the change of attitudes at all levels of society.

- Support to schools with enrolment of children in need of special attention.

- Development and supply of supplementary teaching and learning materials and aids.

- Development of community participation.

- Development of academic, professional and institutional capabilities and capacities at the national and district level.

The development of inclusion and ‘special needs’ education has, until now, been limited to certain disability categories: blindness, deafness, mental disabilities and physical (motor) disability. Since many more children are struggling with learning and participation, a support structure is needed that can reach out to all learners facing barriers.

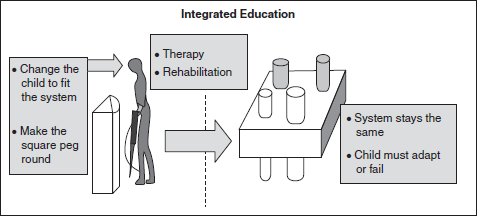

From a traditional perspective, learning and participation problems tend to be seen as a defective condition within the child (see the right panel of the below figure)

From the inclusive perspective, learning difficulties are understood in a full school context assessing the learner, as well as, the context in which learning is taking place see the left panel of the below figure).

Inclusive education and child-friendly school initiatives (discussed in the ensuing text) are both concerned with providing quality education with special emphasis on learners who experience barriers to learning and participation, including those who have a different mother tongue, live in poverty, or from different castes and ethnic groups, with learning difficulties, disabilities and all other disadvantaged groups.

Myths, Misconceptions and Barriers

Reforming school systems has a lot to do with changing the culture of classrooms, schools and universities. The change processes towards inclusion, often, begin on a small scale and involve overcoming some obstacles, such as existing attitudes and values, lack of understanding, lack of necessary teaching skills, limited resource and inappropriate organization. Along with these obstacles, there, also, exist certain myths associated with such practice. Some such myths and misconceptions are:

- IE is, often, misunderstood as a concept that applies to children with disabilities only. This limited disability perspective of IE and the following have become an obstacle for real and inclusive mainstream reform.

- The existing resources are too scarce and do not match the challenge involved.

- There is a need to change societal attitudes first, because inclusion is untenable within the atmosphere of stigma and unfriendly attitudes.

- Inclusion will harm both children without and with disabilities by impeding their progress.

- The basic abilities are lacking among teachers and other education implementers and teaching such children is too difficult.

- Diversity, among students, cannot be accommodated in existing under resourced and overcrowded classrooms.

- The existing curriculum is too difficult for children to follow. Children, with special needs, require a separate curriculum and teaching methods.

- Only professionally trained personnel can work with children with ‘special needs’.

- Meeting the needs of children with ‘special needs’ is the role of the Social Welfare Ministry.

The lack of resources is, often, seen as an insurmountable barrier by many practitioners. In this section, we adapt an article from EENET, Issue 5, “Overcoming resource barrier — an EENET Symposium at ISEC” in which using role-play, the difficulties caused by limited resources and how they have been overcome in developing contexts such as ours in Lesotho, Zambia, Uganda and Nepal, is discussed. The content was prepared collaboratively by a small group of participants who had met for the first time at the pre-congress Presentation Skills workshop at ISEC 2005. Though Spontaneous, yet it was an extremely dynamic and inclusive interaction. We hope you will find the reading useful and may, perhaps, plan to engage your students in a similar exercise, while focusing not only on children with disabilities but also on other groups of marginalized or excluded children, such as very poor children, low-caste children or children from different ethnic groups.

We are all so familiar with the excuses for not introducing more inclusive practices in education. As a planning group, we began with a brainstorm to help us understand and analyze the barriers. We, then, divided the excuses into three categories: people; money and material resources; and information. We realized that most of the excuses, or barriers, fitted into the people category, as they were about negative attitudes — regardless of the level of resourcing. We decided to start the symposium with a brainstorm. This enabled participants to air their own views about resource barriers and engaged them in a practical activity of writing their barriers on pieces of A4 paper. They constructed a wall with their barriers, in answer to the question, ‘What are the barriers to inclusion for all?’ This provided an instant visual aid for the session. It, also, demonstrated the fact that attitudinal barriers were a bigger issue than resource barriers.

Participants were asked to consider the following dialogue when watching the role-play:

‘We don’t have the resources for inclusion!’ ‘Excuse me, but you have a fixed idea about inclusion, which gives you a fixed idea about resources. … If you have a flexible idea about inclusion, you can have a more flexible attitude to resources!.’

We cannot do IE because…

- Attitudes are negative — ‘until attitudes change…’;

- Disabled children are not ready (e.g. not toilet trained);

- It will affect the other children (contagious);

- No capacity to learn;

- Parents’ fear of rejection;

- Teachers are trained in special education — ‘I’ll lose my job’;

- Our people are not literate;

- We have got other priorities;

- Our system is too rigid;

- Buildings are not accessible and

- No trained personnel.

Negative attitudes lead people to say: “We don’t have .… therefore we can’t do.…”

This is, especially, true in the richer countries of the North, where the emphasis is on ‘having’ rather than ‘being’.

However, we challenge this by saying: “We are.…therefore we do”.

My name is Deepa Jain. I am a co-coordinator of an inclusive programme in Delhi, India. I would like to ask you a few questions about inclusion.

First, how can I teach your child when I have not had any training?

My name is Palesa Mphohle and I come from Lesotho. I am a parent of a child with mental disability and I am the co-ordinator of the Lesotho Society of Mentally Handicapped Persons (LSMHP) which is a national organization of parents, founded in 1992.

I, also, did not have any special training to be a parent of a disabled child, but by raising my child and exchanging experiences with other parents, I have realized that I have a lot of knowledge about my child. I can help you to teach my child. In Lesotho, parents work with the Ministry of Education’s IE programme. Problem-based learning in schools is better than any ‘special’ training.

Deepa: Why don’t you send your child to a special school?

Palesa: It is a basic human right that every child should have access to education. My child has been born into our community with his brothers and sisters and should be allowed to go to his neighbourhood school with them. The children do not discriminate. In Lesotho, we have found that non-disabled children, also, benefit from having disabled children in their school. They learn that we are all different and that we must care for one another. These children are our future policymakers. How can they implement policies on inclusion if they have not had any experience of it in their own lives?

My name is John Ndiraba Kiyaga and I am from Uganda. I am the director of Action to Positive Change on People with Disabilities (APCPD) and we run a small school on the outskirts of the capital, Kampala.

When I was a child, my mother wanted me to go to a special school far away from my home because she thought that I would get a better education there. I did not want to go and I persuaded her to let me go to my local school. I worked hard at school and got top grades in all the subjects. Everyone knows me in my community and accepts me for who I am.

Deepa: I think we need to build a special unit attached to the local school.

My name is Paul Mumba. I am a teacher from Zambia. In my experience, building a special unit is still segregation because the children are expected to learn separately. When our unit opened, they sent us a special teacher. He said he was only allowed to teach five children with learning difficulties! The children called him, ‘Teacher of the Fools’.

Deepa: OK, so we agree about inclusion, but I have got 100 children in my class. The disabled child cannot keep up and I have got no resources. What can I do?

Palesa: When teachers complain about the size of their class, I tell them that they should work out ways of reducing its size without excluding my child. What difference will it make if they have one less? Why should it be my child that misses out just because the class size is too big? That is the school’s problem, not my child’s problem.

My name is Krishna Lamichanne and I am from Nepal. I work as a community-based rehabilitation worker in a rural area far from the capital city. We have found that the best thing to do, when a disabled child has a problem, is to get everybody together to have a meeting. We invite the child, their parents and the teachers to discuss the problem and we work out ways to overcome it.

Deepa: But surely we do not have all the answers in our own community?

Palesa: There are lots of useful international documents that can help us in our communities. These are the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), the UN Standard Rules and the Salamanca Statement. We need to know about these international instruments, because they are valuable campaigning tools.

John: We did not want to be dependent on external fund givers when we built our school. We had seen so many projects collapse, after the donors had left, so, instead, we identified locally available resources. We recruited teachers who lived in the community and we set up a mobility aids workshop to provide income for the school. We worked hard to convince the parents that they should send their disabled children to school.

Deepa: Thank you for sharing your experiences. They are very encouraging.

We are sure as you adopt IE approaches, interact with stakeholders and observe grassroots level practice more closely, you and your students will come across some other myths and barriers. We need to all work together, at different levels, to see that the barriers are removed and myths get clarified.

Why Inclusive Education?

The movement towards IE can, also, be justified on the following grounds:

- Educational justification: the requirement for inclusive schools to educate all children together — the rich and the poor, boys and girls, with different abilities, from ethnic, language and cultural minority and majority groups — means that they have to develop ways in teaching that respond to individual differences and, thus, benefit all children.

- Social justification: inclusive schools are able to change attitudes to difference and diversity, by educating all children together and form the basis for a just and tolerant society.

- Economic justification: it is less costly to establish and maintain mainstream schools which provide quality education to all children, than to set up a complex system of different types of schools, specializing in different groups of children.

As teachers, it is also important to note that IE brings quality improvement in teaching and learning because in inclusive and responsive classrooms there is:

- More experience-based, hands-on learning and teaching children to reason.

- More active learning (doing, talking and trying out).

- More responsibility is given to students for their work, goal setting and monitoring.

- More enacting and modelling of the principles of democracy.

- More attention for emotional needs and different cognitive styles of individual students.

- More cooperative activities.

- More reliance upon teachers’ descriptive evaluation of student growth.

AND

- Less whole-class, teacher-directed lecturing and instruction.

- Less passive learning (sitting and listening).

- Less rote memorization.

- Less stress on competition and grading.

- Less tracking and levelling students into ‘ ability groups’.

- Less use of and reliance on standardized tests.

A Child Friendly School (CFS) is (1) a child-seeking school (actively identifying excluded children and provide them with access and learning opportunities) and (2) a child-centred school (acting in the best interest of the ‘whole’ child). |

An Inclusive Learning-Friendly Environment (ILFE) is a formal or non-formal place for learning, where teachers and administrators seek out all available support for finding and teaching all children, while providing special support to children who are enrolled, but excluded from participation and learning. |

CFS reflect an environment of good quality by being:

|

A ‘learning-friendly’ environment is ‘child-friendly’ and ‘teacher-friendly’ and stresses the importance of students and teachers learning together as a learning community. It places children at the centre of learning and encourages their active participation in learning, while, also, fulfilling the needs and interests of teachers. |

Need to Demystify Difference

It is a myth that there are different categories of learners, such as those with ‘special’ and with ‘ordinary’ needs. Education systems have clung to this myth against better judgement. In overcrowded classrooms and where undifferentiated large group instruction is the norm, teachers do not detect individual learning needs. Children, who do not progress in such situations, are easily labelled ‘non-achievers’ or ‘slow learners’. Without the support they need and are entitled to them, subsequently, drop out, while they may find the curriculum irrelevant or have problems to understand the language of instruction.

There is no special education — just education and good teaching is good teaching for all children! Mainstream schools and classrooms need to change into more flexible and resourceful environments. The assumption that there are special schools and learning centres needed for special groups of learners not only serves to divide and exclude but also fails to describe the nature of need, which is regarded as ‘special’. Most factors influencing educational segregation or exclusion have little to do with education. Children from poor homes, working children, migrant workers’ children, and children with disabilities are not out of mainstream schools because of poverty or disability, but because of social prejudice and resistance to change. It has resulted in a situation where disadvantaged children, who have the greatest need of education and of being included in mainstream society, are, thus, the least likely to receive it.

Any child may, at times, suffer exclusion. Critical are those affected in major and permanent ways by where they live (e.g. remote villages, migrant workers’ settlements etc.), how they live (e.g. in poverty, malnourished etc.), what they or their parents do (e.g. sex workers, road workers etc.) and who they are (e.g. with disabilities, from religious minorities etc.). These children are unable to break the cycle of marginalization and discrimination without significant, persistent affirmative action by local communities, national governments and international agencies.

Mainstream systems need to seek out, find and include those learners that have been underserved and mainstream teachers need to learn how to support children for whom learning is difficult due to family circumstances, poverty, earlier experiences, different mother tongue or disability. This should be based on the belief that children, in a classroom, are never homogenous and should not be treated and taught as if they were. There are no ‘special needs’ children. All children have the same needs of belonging, love, security, health, individuality, stimulation and self-esteem and it is normal that the learning needs of individual children differ! ‘Special needs’ has become a new, stigmatizing label which reinforces the deeply entrenched deficit views of ‘difference’, which define certain learners as ‘lacking something’.

‘Special needs’ labels are not useful for teachers, as they say little about how to teach a certain child. A teacher may have two children with learning problems in his/her class that need very different approaches, because children with disabilities are as different from each other as children without disabilities.

Furthermore, many children with disabilities (especially those with visual and hearing impairments) may not have special educational needs at all, provided they are given the assistive devices they need! On the other hand, there are many children who do not have disabilities, but who experience learning problems — arguably all of us do in certain areas, at certain times.

Schools must take up their responsibility to provide quality teaching and learning for all children more seriously. In addition, when seeking explanations for lack of achievement, they must be prepared to consider inadequacies in the teaching-learning conditions, rather than inadequacies in children themselves!

Many of the pioneers of IE were, originally, ardent supporters of special education. However, they have realized the limitations and potential damage of the special needs philosophy and practice, while, also, acknowledging some of its effective approaches, which should now be integrated in quality mainstream education, such as (1) the creative child-focused teaching, responding to individual learning styles, (2) the holistic approach to the child, focusing on all areas of functioning, (3) the close links between families and schools and (4) the development of specific technologies, aids and equipment to facilitate access to education and to help overcome barriers to learning.

For good reasons, much of the attention in the development of IE, to date, has been focused on the school and, particularly, the classroom. However, many of the education barriers may be outside the school — for example at the level of national policy (e.g. IE being an integral part of the mainstream national education policy or not), of the structures of national systems of schooling and teacher education (e.g. IE being part of mainstream teacher education or not) of the way society views diversity (e.g. different ethnic and religious traditions and values included in the mainstream curriculum) of the management of budgets and resources (e.g. rural versus urban schools) etc. IE should be seen in terms of a system-wide quality development, where inclusion is part of the wider attempt to create a more effective system and a more diversity-friendly society.

Most countries in the world (India is not an exception) are multi-cultural, multi-ethnic and multi-lingual and comprise different ways of living. Nevertheless, cultures are, often, seen as monolithic and the voices of the less powerful such as children, those living in poverty, immigrants or people with disabilities may not be heard. Education systems are commonly designed based on homogenous delivery rather than diversity, resulting in marginalization and exclusion, both within and from the systems. IE, ultimately, aims at creating a more inclusive society where difference and diversity is acknowledged, respected and CELEBRATED!

Who Supports Inclusive Education?

The move towards inclusion has involved a series of changes at the societal and classroom level that have been accompanied by elaboration of numerous legal instruments at the international level.

Inclusion has been, implicitly, advocated since the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 and it has been mentioned at all stages in a number of key UN Declarations and Conventions.

How can We Create Inclusive Environments?

We will, now, move on to discus more practical changes at the school level focusing on the role of teachers, parents and educational policy makers, as well as, curricula. However, before doing so, let us spend some more time reflecting on creating conducive environments for learning diversity, as reflected in the following story.

The Animal School: A Fable (by: George Reavis)

Once upon a time, the animals decided they must do something heroic to meet the problems of a ‘new world’ so they organized a school. They had adopted an activity curriculum consisting of running, climbing, swimming and flying. To make it easier to administer the curriculum, all the animals took all the subjects.

The duck was excellent in swimming, in fact, better than her instructor. However, she made only passing grades in flying and was very poor in running. Since she was slow in running, she had to stay after school and, also, drop swimming in order to practise running. This was kept up until her webbed feet were badly worn and she was only average in swimming. However, average was acceptable in school so nobody worried about that, except the duck.

The rabbit started at the top of the class in running, but had a nervous breakdown because of so much makeup work in swimming. The squirrel was excellent in climbing, until he developed frustration in the flying class, where his teacher made him start from the ground up instead of the treetop down. He, also, developed a ‘charlie horse’ from overexertion and, then, got a C in climbing and D in running.

The eagle was a problem child and was disciplined severely. In the climbing class, he beat all the others to the top of the tree, but insisted on using his own way to get there.

At the end of the year, an abnormal eel that could swim exceeding well and, also, run, climb and fly a little, had the highest average and was valedictorian.

The prairie dogs stayed out of school and fought the tax levy because the administration would not add digging and burrowing to the curriculum. They apprenticed their children to a badger and, later, joined the groundhogs and gophers to start a successful private school.

Does this fable have a moral?

Source: EENET Asia Newsletters: Fourth issue, June 2007.

Within the philosophy of IE, it is recognized that problems of non-enrolment, non-attendance, high repetition and dropout rates cannot be solved simply by developing separate policies and systems and special schools. Instead, an approach is needed which views difference as normal and which tries to develop a system that can respond effectively to diversity!

The Cracked Pot

A water bearer in India had two large pots, each hung on the end of a pole which he carried across his neck. One of the pots was perfectly made and never leaked. The other pot had a crack in it and, by the time the water bearer reached his master’s house, it had leaked its water and was only half full.

This went on daily for two years, with the bearer delivering only one and half pots of water to his master’s house. Of course, the perfect pot was proud of its accomplishments. However, the poor cracked pot was ashamed of its own imperfections and was miserable that it was able to accomplish only half of what it had been made to do.

After two years of what it perceived to be a bitter failure, one day it spoke to the water bearer, ‘I am ashamed of myself and I want to apologize to you.’

‘Why?’ asked the bearer. ‘What are you ashamed of?’

‘I have been able, for these past two years, to deliver only half my load because this crack in my side causes water to leak out all the way back to your master’s house. Because of my flaws you have to do all of this work and you do not get full value for your efforts, the pot said.

The water bearer felt sorry for the old, cracked pot, and in his compassion he said, ‘Today, as we return to the master’s house, I want you to notice the beautiful flowers along the path.’

Indeed, as they went up the hill, the old cracked pot took notice of the sun warming the beautiful, wild flowers on the side of the path and this cheered it up a bit. However, at the end of the trail, it still felt bad because it had leaked out half its load and so again the pot apologized to the bearer for its failure.

The bearer said to the pot, “Did you notice that these were flowers only on your side of the path, but not on the other pot’s side? That is because I have always known about your flaws, and I took advantage of it. I planted flower seeds on your side of the path, and every day, while I walked back from the stream, you have watered them. For two years, I have been able to pick these beautiful flowers to decorate my master’s table. Without you being just the way you are, he would not have this beauty to grace his house.”

Each one of us has our own unique flaws. We are all cracked pots. We need not be afraid of our flaws. We need to acknowledge them and we have to learn to convert our weaknesses into our strengths.

Children, too, have their own needs, strengths and weaknesses which we need to cater for in our teaching. A school culture in which all children are valued and welcomed, along with teaching and classroom management methods that are in line with this culture will have a positive impact on all children and adults in a school. The following story helps us understand that inclusion is about all learners.

Knowing How to Teach*

As Ms. Sharma stood in front of her fifth-grade class on the first day of school, she told the children something that was not true. Like most teachers, she looked at her students and said that she liked them all. However, that was impossible, because there, in the front row, slumped in his seat, was a little boy named Rahul.

She had watched Rahul the year before and noticed that he did not play well with other children and that his work was messy. In addition, Rahul could be unpleasant. It got to the point where Ms. Sharma would, actually, take delight in marking his papers with a thick red pen, making bold Xs and then putting a big “F” at the top of his papers. At the school where Ms. Sharma taught, it was required to review each child’s past records. She put Rahul off until the very end. However, when she reviewed his file, she was in for a surprise.

Rahul’s first-grade teacher wrote: ‘Rahul is a bright child with a ready laugh. He does his work neatly and has good manners.… He is a joy to have around.’ His second-grade teacher wrote: ‘Rahul is an excellent student, well liked by his classmates, but he is troubled because his mother has a terminal illness and life at home must be a struggle.’ His third-grade teacher wrote: ‘His mother’s death has been hard on him. He tries to do his best, but his father doesn’t show much interest and his home life will soon affect him, if no steps are taken.’ Rahul’s fourth-grade teacher wrote: ‘Rahul is withdrawn and doesn’t show much interest in school. He doesn’t have many friends and he, sometimes, sleeps in class.’

By now, Ms. Sharma realized the problem and felt extremely uneasy and ashamed of herself. She felt even worse when her students brought her Christmas presents, wrapped in beautiful ribbons and bright paper, except for Rahul. His present was clumsily wrapped in the heavy, brown paper that he probably found somewhere lying around. Ms. Sharma took pains to open it in the middle of the other presents. Some of the children started to laugh when inside she found a bracelet with some of the stones missing and a bottle that was one-half full of perfume. However, she stifled the children’s laughter when she exclaimed how pretty the bracelet was while putting it on, and dabbing some of the perfume on her wrist. Rahul stayed after school that day just long enough to say: ‘Ms. Sharma, today you smelled just like my mom used to.’

After the children left, she cried. On that very day, she decided to stop just teaching reading, writing and arithmetic. Ms. Sharma decided to try to understand her children as individuals and, as she did so, she became a different person. She talked and joked with them and in, particular, applauded Rahul’s achievements. She spent time talking to him and, soon, he began to respond to her loving care. By the end of the year, Rahul had become a confident learner.

A year later, she found a note under her door from Rahul telling her that she was the best teacher he ever had. Six years went by, before she got yet another note from Rahul. He wrote that he had finished high school, stood third in his class and she was still his best teacher. Four years after that, she got yet another letter, saying that while things had been tough at times, he had held on and would soon graduate from college in India with the highest honours. Ms. Sharma was still his best teacher!

Then, four years passed and yet another letter came. This time he explained that after he got his bachelor’s degree, he decided to go a little further. The letter explained that she was still the best and favourite teacher he ever had. However, now, his name was a little longer. The letter was signed, Rahul Mahajan, M.D.

The story does not end there. You see, there was another letter that spring. Rahul said he met a girl and was going to be married. He explained that his father had died a couple of years ago and he was wondering if Ms. Sharma might agree to sit at the wedding in the place that was, usually, reserved for the mother of the groom. Of course, Ms. Sharma did. And, guess what? She wore that bracelet, the one with several stones missing. Moreover, she made sure she was wearing the perfume that Rahul remembered his mother wearing on their last Dushera together.

They hugged each other and Dr. Mahajan whispered in Ms. Sharma’s ear, ‘Thank you, Ms. Sharma for believing in me. Thank you for making me feel important and showing me that I could make a difference.’ Ms. Sharma, with tears in her eyes, whispered back, ‘Rahul, you have it all wrong. You were the one who taught me that I could make a difference. I did not know how to teach, until I met you.’

Most children that experience barriers to learning (e.g. those from ethnic, language or cultural minorities; those from poor families; those with different disabilities or learning problems, and working children) do not need different or special education — they need more flexible and individualized education. As mentioned, barriers to learning can be located within the child, within the teaching-learning methods, within the school, the education system and the broader social, economic and political contexts. Such barriers manifest themselves in different ways and only become obvious when learning breakdown occurs. Effective teaching and learning is directly related to, and dependent on, the social and emotional well-beings of the learner. It is important to recognize that particular conditions may arise in the lives of children, which impact negatively on their emotional well-being (e.g. domestic violence, exploitation, sexual abuse etc.), thus placing the child at risk of learning breakdown. Inclusive, effective teachers are observant to signs that reveal a child’s emotional well-being. A good teacher helps children learn not only academically but also emotionally and socially. Such a teacher looks for children’s individual strengths and weaknesses, and, thus, for their individual learning and development needs and addresses those effectively.

Negative attitudes and certain assumptions regarding difference and diversity in society, for example related to socio-economic status or disability, remain critical barriers to development. For most part, such negative attitudes manifest themselves in the labelling of learners. Sometimes, these labels are just negative associations between the learner and the system such as ‘drop-outs’, ‘repeaters’ or ‘slow learners’ and while it is important to recognize the impact of such labels on a child’s self-esteem, the most serious consequence of such labelling results when it is linked to school placement or exclusion. Teachers may look for excuses for poor learning results in having many ‘slow learners’ and ‘repeaters’ in their class. They may even point them out, not realizing what this will do to a child’s feelings. Teachers must become more reflective regarding their own practices and change their methods to help different children learn in different ways. It is critical to reflect on teachers’ roles in creating or reducing barriers to learning, as their attitudes and behaviour can either enhance or impede a child’s ability to learn.

Teachers and other adults, may, in that respect, not always be such good role models for children. How, for example, can we expect children to learn to be tolerant and respectful to others, if adults continue to ridicule certain children? And, how can we expect children to learn to resolve conflicts in non-violent ways, if adults continue to use corporal punishment on children?

Factors such as the classroom’s physical environment, the child’s level of psychological comfort in the classroom and the quality of interaction between the teacher and the child affect whether, and to what extent, a child is able to learn and develop to his or her full potential.

IE focuses on what children can do and on their potential for further learning, rather than on failings and shortcomings. This means that teachers need to create learning environments, where all children are encouraged and enabled to reach their potential and where all children feel comfortable about who they are, where they come from, and what they believe in.

Inclusion

Inclusion is the future.

Inclusion is belonging to one race — the human race.

Inclusion is basic human right.

Inclusion is struggling to figure out how to live with one another.

Inclusion is something you do to someone or for someone.

Inclusion is something we do with one another.

It either is or isn’t.

Marsha Forest

An effective support system is essential, if schools are to become inclusive and give every child the opportunity to become a successful learner. ‘Support’ includes everything that enables children to learn. The most important forms of support are available to every school: children supporting children, teachers supporting teachers, parents becoming partners in the education of their children and communities supporting their local schools. There are, also, more formal types of support to mainstream inclusive schools, such as from teachers with specialist knowledge, resource centres and professionals from other sectors.

To facilitate and sustain the process towards educational inclusion, extra financial resources may be needed, however, such resources are needed for better quality education in general! Poor education provision is very costly as it, often, results in high repetition and dropout rates and poor learning achievements. Part of the process towards IE requires a critical analysis on why the mainstream system is not successful in providing good quality education for all. It, also, asks for the identification of existing resources and innovative practices in local contexts and examining barriers to participation and learning. Improving the mainstream system, from an inclusive perspective, benefits all children.

Using Correct Terminology

In this section, we draw your attention to the fact that words are important and teachers, in particular, must make sure that words do not offend or reinforce negative stereotypes. Negative and patronizing language produces negative and patronizing images.

Language can be used to shape ideas, perceptions and attitudes. Words that are in popular use reflect prevailing attitudes in society. Those attitudes are, often, the most difficult obstacles to change. However, positive and respectful attitudes can be shaped through careful use of words that, objectively, explain and inform without judgemental implications.

Words such as impairment, disability and handicap are, often, used interchangeably. The World Health Organization (WHO) carefully defines these three words (see box), but has, in the meantime, decided that these are no longer acceptable in terms of human rights and respect for difference and diversity. Disability is, now, seen as a complex collection of conditions, many of which are created by the social environment. Hence, the management of the problem requires social action and it is the collective responsibility of society, at large, to make the environmental modification necessary for the full participation of children and adults with disabilities in all areas of life.

The issue is, therefore, an attitudinal or ideological one requiring social change, which at the political level becomes a question of human rights. Disability becomes, in short, a political issue!

Impairment: This word refers to an abnormality in the way organs or systems function. Impairment, usually, refers to a medical or organic condition, e.g. short-sightedness, heart problems, cerebral palsy or hearing problems.

Disability: This is the functional consequence of impairment. A child with spina bifida who, because of this impairment cannot walk without the assistance of callipers and crutches, has a disability. However, a person with short-sightedness, who is provided with correcting glasses may see very well and, thus, has impairment, but no disability!

Handicap: This is the social or environmental consequence of a disability. Many people with a disability do, in principle, not feel handicapped. Society, often, makes them handicapped by creating barriers of rejection, discrimination, prejudice and physical access, preventing them from making choices and decisions that affect their lives. For example, if a child who uses a wheelchair cannot enter the community school, he or she will have a handicap in making use of the school. When the school is made accessible for users of wheelchairs, this handicap disappears. Handicaps do, often, reveal the (lack of) flexibility, resources and attitudes of a community in which the person is living.

When talking about persons with a disability, people, often, use words or labels that imply a negative judgement. People say that persons are disabled, are deaf or are mentally retarded, as if that is their only characteristic. Persons are not impaired, disabled or handicapped, but they may have an impairment, disability or handicap as one of their many characteristics.

Talking about ‘the handicapped’, ‘the disabled’ and ‘the deaf’ is rather insulting and hurtful to a person’s dignity. It devalues people and labels them, reinforcing stereotyping. Such labels focus, primarily, on the disability and not on the person. A disability should be considered as one of many other characteristics of the person.

‘Mental retardation’ is another negative label, which hurts the person in question, as well as, his/her family members. It is preferred to use the term ‘intellectual disability’, instead of mental retardation.

As teachers, we need to keep in mind that diversity among people is normal and that, within the different categories of disabilities, people differ as much from each other as within other groups of people. A teacher may have two children with visual impairments in his/her classroom that require very different teaching approaches, due to such normal diversity among people with and without disabilities.

Children, who Learn Together, Learn to Live Together: What Does an Inclusive classroom Look Like?

Most of us look at classrooms as places for serious learning and seldom as a place where students enjoy activities and have a say in what and how they need and want to learn. Classrooms consist of students, who, hopefully, are interested in gaining new knowledge and skills, and teachers, who, hopefully, can facilitate optimal learning to all those different children. The most important part of teaching and learning is the learning environment, especially the ways how teachers and students interact and how such an environment helps different children learn to their best ability.

An inclusive learning environment is not only a place for formal learning but also a place where children have rights: the right to be healthy, to be loved, to be treated with respect, the right to be protected from violence and abuse (including physical or mental punishments) and the right to express his or her opinion and to be supported in education irrespective of learning needs. Such learning environments are, also, defined as child-friendly learning environments.

What are the Characteristics of an inclusive child-Friendly classroom?

- An inclusive and child-friendly classroom does not discriminate, exclude or marginalize any child based on gender, socio-economic background, ethnicity, abilities or disabilities etc. This means that:

- No child is refused enrolling and attending classes for whatever reason.

- Boys and girls have equal learning opportunities.

- Children are all treated the same with respect.

- An inclusive and child-friendly classroom is effective with children, facilitates and supports education of good quality and is child centred. This means that:

- Teachers think about the best interest of each child, when deciding on learning activities.

- Teachers try to adjust the standard curriculum to the learning needs of the students.

- Different teaching methods are used, so that all children can learn, those who learn best by doing, hearing, seeing, moving etc.

- Teaching-learning approaches are used that invite students to think and reason and express their opinions.

- All children are supported to learn and master the basic skills of reading (and listening), writing and arithmetic.

- Children, also, learn by experiencing/discovery and by working together.

- Teachers encourage children to express their feelings through arts and other forms.

- An inclusive and child-friendly classroom is healthy for children. This means that:

- What happens in the classroom, also, promotes children’s health.

- Classrooms/schools are clean, safe and have adequate water and sanitation facilities.

- There are written policies and regular practices that promote good health.

- Health education and life skills are integrated in the curriculum and the teaching-learning activities.

- An inclusive and child-friendly classroom is caring and protective of all children. This means that:

- Children are secure and protected from harm and abuse.

- Children are encouraged to care for each other.

- No physical or mental punishment is used with children.

- There are clear guidelines for conduct between teachers and students and among students (and no bullying is allowed).

- An inclusive and child-friendly classroom involves families and communities. This means that:

- Parents are invited and consulted about the learning of their children.

- Teachers and parents work together to help children learn better in school and at home.

- Teachers and parents, together, care about the children’s health, nutrition and safety — also on the way to and from school.

- Parents and community members are invited for school-community project activities.

What are the Objectives and Goals of an Inclusive and Child-Friendly Classroom?

Goal 1: Encourage children’s participation in the school and community.

Goal 2: Enhance children’s health and well-being.

Goal 3: Guarantee safe and protective environments for children.

Goal 4: Encourage optimal enrolment and completion.

Goal 5: Ensure children’s optimal academic achievement and success.

Goal 6: Raise teachers’ motivation and success.

Goal 7: Mobilize parent and community support for education.

What Role Can Teachers and Students Play to Reach These Goals?

If all teachers and students work together and schools try to become inclusive and child-friendly schools, many of these goals can be achieved as part of the whole school development. If individual teachers try to make their classrooms more inclusive and child-friendly, they may only reach parts of these goals, but these are good first steps. Individual teachers can make their classrooms more inclusive and child-friendly, by trying to implement some of the action points mentioned below.

Goal 1: Participation

- I have made my classroom a welcoming place for all children, also for those from very poor families, those with language difficulties, those with disabilities and those who learn slower than others.

- I involve my students in class meetings, where we discuss and decide on matters that concern their well-being.

- I organize, together with my students, learning activities involving parents and community members, while, also, going out into the community for project learning activities.

- I organize, with my students, a classroom bulletin board or student opinion box, so students can express their ideas and views about school and community issues.

- I arrange different seating arrangements for my class to facilitate different ways of learning and participation.

- I, especially, make sure that students, who are shy or who have learning difficulties, are, also, participating and learning adequately.

Goal 2: Health and Well-Being

- I maintain and regularly update the health records of my students and refer students with problems to health centres.

- I use simple assessment tools to find out whether or not students have hearing, vision or other problems.

- I teach (and role-model) proper waste disposal in my classroom and in the school.

- There are separate toilets for boys and girls and they are kept clean.

Goal 3: Safety and Protection

- My classroom has proper ventilation, lighting and enough space for all students.

- Classroom furniture is sufficient and sized to the age of my students.

- My classroom layout and furniture allow students to interact and do group work.

- My classroom has a bulletin board or a corner that displays helpful learning materials such as posters, illustrations, low-cost and self-made teaching-learning aids, newspaper and magazine clippings and my students’ own work.

- My classroom is maintained and kept clean.

- I have, together with my students, developed classroom rules on how to respect and help each other and on how to behave.

- I have identified different learning needs and difficulties of my students and I provide additional support while, also, asking students to help each other.

- I use positive discipline methods.

Goal 4: Enrollment and Completion

- I try to find out whether or not there are children not coming to school and the reasons why. I will encourage children, who are not in school, to come to school.

- I discuss with students and parents/community members the problem of non-enrolment and how to get all children of school age into school.

- I regularly check on the attendance of my students and address problems concerning non-attendance.

Goal 5: Academic Success

- I know and implement my school’s vision and mission.

- I am familiar with child-centred and child-friendly teaching-learning approaches.

- I ask my students what they already know about a topic, before I start teaching.

- I have sufficient books and teaching aids for my students’ optimal learning.

- I plan and prepare lessons well, while keeping in mind that children have different learning needs and learning styles.

- I have interesting pictures, posters and students’ work on the walls of my classroom.

- I encourage and implement cooperative learning and discovery/active learning (‘learning by doing’) with my students.

- I make topics more interesting and relevant to children’s lives, by inviting community members or parents to the classroom or by going out of the classroom or by using locally available resources as teaching-learning aids.

- I use formative assessment to make sure children are learning and I adjust my teaching methods and contents, if needed.

- I observe and listen to my students and document their learning process and progress.

- I, often, ask open-ended questions to find out how my students think and reason.

- I do not punish my students for giving the wrong answer or solution, but treat mistakes as new opportunities for learning.

Goal 6: Motivation of Teachers

- I try to find ways to further develop professionally, through reading about education, more training or in-service workshops.

- I am professionally supported by the head of school and he or she encourages us to work together as teachers, to support each other.

- I ask the head of school to monitor my performance and identify my areas of strengths (to be shared with other teachers) and weakness (for further professional development).

Goal 7: Community Support

- I invite parents or community members to my classroom to show what is happening in the classroom or for project presentations by the students.

- I meet and discuss with parents and community members matters of concern, such as safety, when going to and from school; violence and abuse risks; allowing children with ‘special needs’ into the school and supporting them; irregular attendance etc.

- I organize literacy classes for illiterate parents.

- I ask parents and communities to contribute to the learning of their children in different ways, while my students can, also, contribute to community needs with special projects.

Staring Down the Curriculum Monster

In the process towards more IE, the curriculum may be a major obstacle but, at the same time, also, an important tool for change. The nature of the curriculum, at all phases of education, involves a number of components, which are all important in facilitating or undermining effective learning. Key components of the curriculum include the style and tempo of teaching and learning, the relevance of what is being taught, the way the classroom is managed and organized and materials and equipment used in the teaching-learning process. Developing a curriculum, which is inclusive of all learners, may involve broadening current definitions of learning. Though there is a need for a basic standard curriculum, it should be flexible enough to respond to the needs of all students. It should, therefore, not be rigidly prescribed at a national or central level. Inclusive curricula are constructed flexibly to allow, not only for school-level adaptations and developments, but also for modifications to meet the individual student’s needs. Teachers must learn how to adjust a basic, standard curriculum, in such a way, that it becomes relevant and learning-friendly for different children. It is important to realize that the process of how knowledge, skills and values are transmitted is as important a part of the curriculum as what is learned. IE research and pilot programmes from all over the world — including many low-income countries — suggest some key elements for more inclusive curricula, leaving room for schools and individual teachers to develop adaptations that make better sense in the local context and for the individual learner, such as, for example, assessment based on individual progress rather than on peer competition. Such curricula should not only value academic learning but also teach and model understanding and acceptance of diversity.

Inflexible and content-heavy curricula are, usually, the major cause of segregation and exclusion within a classroom….

From: Open File on Inclusive Education(UNESCO).

Formative Assessment Supportive of Inclusive and Responsive Teaching-Learning

Why do teachers assess students? What do we exactly want to assess and why? Are we collecting information in order to provide documentation of individual student progress? Do we assess to be able to convey our expectations to students? Or, will the information gathered be used to guide or change our teaching? If it is any or all of these, the focus of our assessment is formative and on individual students.

If, instead, data are collected to monitor the outcomes of groups of students or schools and are to be used as a basis for planning and implementing programme improvements, or to provide guidance for the allocation of resources to a programme, the assessment is most, likely, summative and not focusing on individual students.

Teachers ask their students questions so that they know how students are doing and so that students know what else they need to learn. Such assessments can be formative or summative. It is summative when it summarizes what students have learned at the end of an instructional segment, mostly resulting in a score or grade. This kind of assessment dominates in many schools and education systems as their results, typically, ‘count’ and appear on report cards. Summative assessment is, by itself, an inadequate tool for maximizing learning, because waiting till the end of a teaching period to find out how well students have learned is simply too late. In many classrooms and schools, assessment is, also, increasingly used to compare students with one another. This checking and sorting function of assessment tends to dominate in most schools. Grades and scores for different school work, sorts and tracks individuals, separating the ‘qualified’ from those judged less qualified.

Such assessment, also, serves a reporting function: parents, policy makers and teachers look to the different summative assessment tools as proof that students are learning. However, research is, increasingly, revealing that this may not be so for many children.

Thus, how can we reclaim assessment as a way to adjust teaching and learning and enable all students to learn whatever their individual learning differences and needs? How can teachers use assessment to focus on improved learning? Formative assessment may be one of the answers.

Every day, teachers observe students, listen to their conversations and talk with them about their ideas, writings and other work. Teachers try to understand and enhance the students’ thinking and skills. This daily information or input helps teachers to decide what next steps to take to further support student learning and development. When these things are done in a purposeful way, it becomes continuous formative assessment (CFA).

What we need in our schools is a shift from quality control in learning to quality assurance or accountability. Traditional approaches to instruction and assessment involve teaching certain material, and at the end of the teaching, working out who has and who has not learned it — similar to quality control in manufacturing. Assessment for learning though involves adjusting teaching as needed, while the teaching and learning is still taking place — a quality assurance approach. Such quality assurance, also, involves a change of attention from teaching to learning. The emphasis is on what students get out of the process, rather than on what teachers are putting into it. It requires an approach to teaching that facilitates learning and where students, rather than teachers, do most of the work!

Formative assessment kind of blurs the line between teaching and assessment. If done well, assessment is difficult to distinguish from instruction. Everything students do — talking in groups, completing seat-work, asking and answering questions, working on projects, handing in assignments, even sitting silently and looking confused — is a potential source of information for a teacher about how much they understand.

Teachers, who, consciously, use assessment to support learning, take in this information, analyze it, and make instructional decisions that respond to the understandings and misunderstandings that such assessments reveal. As such, CFA is an inclusive strategy that helps teachers to better respond to learning diversity.

Research — consistent across countries, content areas and age groups — shows that using assessment for learning improves student achievement more than external tests or educational reforms. In addition, the research tells us that:

“…Formative assessment helps low achievers more than other students and so reduces the achievement gaps while raising overall standards.…”(1)

On-going assessment and adjustments, on the part of both teacher and student, support the process for optimal learning of every student. Some strategies that facilitate assessment for learning that teachers of all content areas and all levels can use are:

- Clarifying and sharing learning intentions and criteria for success.

- For example: Students may understand learning objectives better when the teacher circulates work samples that a previous class completed, in prompting discussions about quality. Students decide what is good and what is still lacking in the weaker work samples. It helps them to apply better standards themselves.

- Facilitating effective classroom discussions, questions and learning tasks.

- For example: Teachers often spend a lot of time on whole class question-answer sessions. Such sessions check existing knowledge rather than facilitating new learning. Moreover, teachers mostly listen for the ‘correct’ answer. Open-ended questions that enable students to reflect on, clarify and explain their thinking may provide more valuable information for teachers than just a ‘correct’ answer. Questions need to be well planned to either prompt students’ thinking or to provide teachers with information that they can use to adjust teaching to meet learning needs.

- Providing feedback that helps learners to move forward.

- For example: Grades, scores or comments such as ‘good job’ do not make students think. What does cause thinking is feedback that mentions what a student needs to do to improve.

- Activating students as the owners of their own learning.

- For example: Students indicate, with red or green cards to the teacher, whether they have understood or not. Students are allowed to assess their own work.

- Activating students as teaching resources for one another.

- For example: Peer assessment and peer feedback, which focuses on improvements (without grading), because peers, often, communicate more effectively with each other, than adults do with students.

Teaching practices that support these strategies are low-tech, low cost and feasible for individual teachers to implement. As such, they differ greatly from large-scale interventions such as class-size reduction or curriculum reforms which are difficult to initiate or influence by teachers.

Teachers, using assessment for learning, continually look for ways in which they can generate evidence of student learning and they use this evidence to adapt their teaching to better meet their students’ learning needs. Questions and answers, in such a learning environment, decide the direction of instruction, because it reveals how students are thinking and reasoning. This, also, highlights why it is important to ask students who provide correct answers, how they got their answer.

Another assessment for learning is diagnostic or pre-assessment, preceding instruction. Teachers use this kind of assessment to check students’ prior knowledge and skill levels, learners’ interests and learning styles. Pre-assessments provide information to help teachers plan their lessons and to guide differentiated instruction.

(Continuous) formative assessment includes both formal and informal tools, such as ungraded quizzes (e.g. true—false quizzes), purposeful questioning, teacher observations, draft assignments, think-alouds, learning logs and portfolio reviews. Formative assessment outcomes, though, must never result in summative evaluation and grading!

We can make learning more meaningful and sustainable also in summative assessment, by focusing performance goals not on recall of facts or memorized formulas, but on how students transfer knowledge and how they use their knowledge and skills in new situations, thereby demonstrating their understanding and content standards. It, certainly, helps students to see reasons for their learning.