Chapter 6. Interfaces, Lambda Expressions, and Inner Classes

In this chapter

You have now learned about classes and inheritance, the key concepts of object-oriented programming in Java. This chapter shows you several advanced techniques that are commonly used. Despite their less obvious nature, you will need to master them to complete your Java tool chest.

The first technique, called interfaces, is a way of describing what classes should do, without specifying how they should do it. A class can implement one or more interfaces. You can then use objects of these implementing classes whenever conformance to the interface is required. After discussing interfaces, we move on to lambda expressions, a concise way to create blocks of code that can be executed at a later point in time. Using lambda expressions, you can express code that uses callbacks or variable behavior in an elegant and concise fashion.

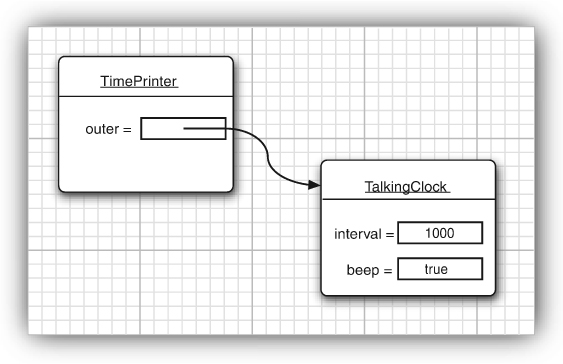

We then discuss the mechanism of inner classes. Inner classes are technically somewhat complex—they are defined inside other classes, and their methods can access the fields of the surrounding class. Inner classes are useful when you design collections of cooperating classes.

This chapter concludes with a discussion of proxies, objects that implement arbitrary interfaces. A proxy is a very specialized construct that is useful for building system-level tools. You can safely skip that section on first reading.

6.1 Interfaces

In the following sections, you will learn what Java interfaces are and how to use them. You will also find out how interfaces have been made more powerful in recent versions of Java.

6.1.1 The Interface Concept

In the Java programming language, an interface is not a class but a set of requirements for the classes that want to conform to the interface.

Typically, the supplier of some service states: “If your class conforms to a particular interface, then I’ll perform the service.” Let’s look at a concrete example. The sort method of the Arrays class promises to sort an array of objects, but under one condition: The objects must belong to classes that implement the Comparable interface.

Here is what the Comparable interface looks like:

public interface Comparable

{

int compareTo(Object other);

}

In the interface, the compareTo method is abstract—it has no implementation. A class that implements the Comparable interface needs to have a compareTo method, and the method must take an Object parameter and return an integer. Otherwise, the class is also abstract—that is, you cannot construct any objects.

![]() NOTE:

NOTE:

As of Java 5, the Comparable interface has been enhanced to be a generic type.

public interface Comparable<T>

{

int compareTo(T other); // parameter has type T

}

For example, a class that implements Comparable<Employee> must supply a method

int compareTo(Employee other)

You can still use the “raw” Comparable type without a type parameter. Then the compareTo method has a parameter of type Object, and you have to manually cast that parameter of the compareTo method to the desired type. I will do just that for a little while so that you don’t have to worry about two new concepts at the same time.

All methods of an interface are automatically public. For that reason, it is not necessary to supply the keyword public when declaring a method in an interface.

Of course, there is an additional requirement that the interface cannot spell out: When calling x.compareTo(y), the compareTo method must actually be able to compare the two objects and return an indication whether x or y is larger. The method is supposed to return a negative number if x is smaller than y, zero if they are equal, and a positive number otherwise.

This particular interface has a single method. Some interfaces have multiple methods. As you will see later, interfaces can also define constants. What is more important, however, is what interfaces cannot supply. Interfaces never have instance fields. Before Java 8, all methods in an interface were abstract. As you will see in Section 6.1.4, “Static and Private Methods,” on p. 322 and Section 6.1.5, “Default Methods,” on p. 323, it is now possible to have other methods in interfaces. Of course, those methods cannot refer to instance fields—interfaces don’t have any.

Now, suppose we want to use the sort method of the Arrays class to sort an array of Employee objects. Then the Employee class must implement the Comparable interface.

To make a class implement an interface, you carry out two steps:

1. You declare that your class intends to implement the given interface.

2. You supply definitions for all methods in the interface.

To declare that a class implements an interface, use the implements keyword:

class Employee implements Comparable

Of course, now the Employee class needs to supply the compareTo method. Let’s suppose that we want to compare employees by their salary. Here is an implementation of the compareTo method:

public int compareTo(Object otherObject)

{

Employee other = (Employee) otherObject;

return Double.compare(salary, other.salary);

}

Here, we use the static Double.compare method that returns a negative if the first argument is less than the second argument, 0 if they are equal, and a positive value otherwise.

![]() CAUTION:

CAUTION:

In the interface declaration, the compareTo method was not declared public because all methods in an interface are automatically public. However, when implementing the interface, you must declare the method as public. Otherwise, the compiler assumes that the method has package access—the default for a class. The compiler then complains that you’re trying to supply a more restrictive access privilege.

We can do a little better by supplying a type parameter for the generic Comparable interface:

class Employee implements Comparable<Employee>

{

public int compareTo(Employee other)

{

return Double.compare(salary, other.salary);

}

. . .

}

Note that the unsightly cast of the Object parameter has gone away.

![]() TIP:

TIP:

The compareTo method of the Comparable interface returns an integer. If the objects are not equal, it does not matter what negative or positive value you return. This flexibility can be useful when you are comparing integer fields. For example, suppose each employee has a unique integer id and you want to sort by the employee ID number. Then you can simply return id - other.id. That value will be some negative value if the first ID number is less than the other, 0 if they are the same ID, and some positive value otherwise. However, there is one caveat: The range of the integers must be small enough so that the subtraction does not overflow. If you know that the IDs are not negative or that their absolute value is at most (Integer.MAX_VALUE - 1) / 2, you are safe. Otherwise, call the static Integer.compare method.

Of course, the subtraction trick doesn’t work for floating-point numbers. The difference salary - other.salary can round to 0 if the salaries are close together but not identical. The call Double.compare(x, y) simply returns -1 if x < y or 1 if x > y.

![]() NOTE:

NOTE:

The documentation of the Comparable interface suggests that the compareTo method should be compatible with the equals method. That is, x.compareTo(y) should be zero exactly when x.equals(y). Most classes in the Java API that implement Comparable follow this advice. A notable exception is BigDecimal. Consider x = new BigDecimal("1.0") and y = new BigDecimal("1.00"). Then x.equals(y) is false because the numbers differ in precision. But x.compareTo(y) is zero. Ideally, it shouldn’t be, but there was no obvious way of deciding which one should come first.

Now you saw what a class must do to avail itself of the sorting service—it must implement a compareTo method. That’s eminently reasonable. There needs to be some way for the sort method to compare objects. But why can’t the Employee class simply provide a compareTo method without implementing the Comparable interface?

The reason for interfaces is that the Java programming language is strongly typed. When making a method call, the compiler needs to be able to check that the method actually exists. Somewhere in the sort method will be statements like this:

if (a[i].compareTo(a[j]) > 0)

{

// rearrange a[i] and a[j]

. . .

}

The compiler must know that a[i] actually has a compareTo method. If a is an array of Comparable objects, then the existence of the method is assured because every class that implements the Comparable interface must supply the method.

![]() NOTE:

NOTE:

You would expect that the sort method in the Arrays class is defined to accept a Comparable[] array so that the compiler can complain if anyone ever calls sort with an array whose element type doesn’t implement the Comparable interface. Sadly, that is not the case. Instead, the sort method accepts an Object[] array and uses a clumsy cast:

// approach used in the standard library--not recommended

if (((Comparable) a[i]).compareTo(a[j]) > 0)

{

// rearrange a[i] and a[j]

. . .

}

If a[i] does not belong to a class that implements the Comparable interface, the virtual machine throws an exception.

Listing 6.1 presents the full code for sorting an array of instances of the class Employee (Listing 6.2).

Listing 6.1 interfaces/EmployeeSortTest.java

1 package interfaces;

2

3 import java.util.*;

4

5 /**

6 * This program demonstrates the use of the Comparable interface.

7 * @version 1.30 2004-02-27

8 * @author Cay Horstmann

9 */

10 public class EmployeeSortTest

11 {

12 public static void main(String[] args)

13 {

14 var staff = new Employee[3];

15

16 staff[0] = new Employee("Harry Hacker", 35000);

17 staff[1] = new Employee("Carl Cracker", 75000);

18 staff[2] = new Employee("Tony Tester", 38000);

19

20 Arrays.sort(staff);

21

22 // print out information about all Employee objects

23 for (Employee e : staff)

24 System.out.println("name=" + e.getName() + ",salary=" + e.getSalary());

25 }

26 }

Listing 6.2 interfaces/Employee.java

1 package interfaces;

2

3 public class Employee implements Comparable<Employee>

4 {

5 private String name;

6 private double salary;

7

8 public Employee(String name, double salary)

9 {

10 this.name = name;

11 this.salary = salary;

12 }

13

14 public String getName()

15 {

16 return name;

17 }

18

19 public double getSalary()

20 {

21 return salary;

22 }

23

24 public void raiseSalary(double byPercent)

25 {

26 double raise = salary * byPercent / 100;

27 salary += raise;

28 }

29

30 /**

31 * Compares employees by salary

32 * @param other another Employee object

33 * @return a negative value if this employee has a lower salary than

34 * otherObject, 0 if the salaries are the same, a positive value otherwise

35 */

36 public int compareTo(Employee other)

37 {

38 return Double.compare(salary, other.salary);

39 }

40 }

![]() NOTE:

NOTE:

According to the language standard: “The implementor must ensure sgn(x.compareTo(y)) = -sgn(y.compareTo(x)) for all x and y. (This implies that x.compareTo(y) must throw an exception if y.compareTo(x) throws an exception.)” Here, sgn is the sign of a number: sgn(n) is –1 if n is negative, 0 if n equals 0, and 1 if n is positive. In plain English, if you flip the parameters of compareTo, the sign (but not necessarily the actual value) of the result must also flip.

As with the equals method, problems can arise when inheritance comes into play.

Since Manager extends Employee, it implements Comparable<Employee> and not Comparable<Manager>. If Manager chooses to override compareTo, it must be prepared to compare managers to employees. It can’t simply cast an employee to a manager:

class Manager extends Employee

{

public int compareTo(Employee other)

{

Manager otherManager = (Manager) other; // NO

. . .

}

. . .

}

That violates the “antisymmetry” rule. If x is an Employee and y is a Manager, then the call x.compareTo(y) doesn’t throw an exception—it simply compares x and y as employees. But the reverse, y.compareTo(x), throws a ClassCastException.

This is the same situation as with the equals method discussed in Chapter 5, and the remedy is the same. There are two distinct scenarios.

If subclasses have different notions of comparison, then you should outlaw comparison of objects that belong to different classes. Each compareTo method should start out with the test

if (getClass() != other.getClass()) throw new ClassCastException();

If there is a common algorithm for comparing subclass objects, simply provide a single compareTo method in the superclass and declare it as final.

For example, suppose you want managers to be better than regular employees, regardless of salary. What about other subclasses such as Executive and Secretary? If you need to establish a pecking order, supply a method such as rank in the Employee class. Have each subclass override rank, and implement a single compareTo method that takes the rank values into account.

6.1.2 Properties of Interfaces

Interfaces are not classes. In particular, you can never use the new operator to instantiate an interface:

x = new Comparable(. . .); // ERROR

However, even though you can’t construct interface objects, you can still declare interface variables.

Comparable x; // OK

An interface variable must refer to an object of a class that implements the interface:

x = new Employee(. . .); // OK provided Employee implements Comparable

Next, just as you use instanceof to check whether an object is of a specific class, you can use instanceof to check whether an object implements an interface:

if (anObject instanceof Comparable) { . . . }

Just as you can build hierarchies of classes, you can extend interfaces. This allows for multiple chains of interfaces that go from a greater degree of generality to a greater degree of specialization. For example, suppose you had an interface called Moveable.

public interface Moveable

{

void move(double x, double y);

}

Then, you could imagine an interface called Powered that extends it:

public interface Powered extends Moveable

{

double milesPerGallon();

}

Although you cannot put instance fields in an interface, you can supply constants in them. For example:

public interface Powered extends Moveable

{

double milesPerGallon();

double SPEED_LIMIT = 95; // a public static final constant

}

Just as methods in an interface are automatically public, fields are always public static final.

![]() NOTE:

NOTE:

It is legal to tag interface methods as public, and fields as public static final. Some programmers do that, either out of habit or for greater clarity. However, the Java Language Specification recommends that the redundant keywords not be supplied, and I follow that recommendation.

While each class can have only one superclass, classes can implement multiple interfaces. This gives you the maximum amount of flexibility in defining a class’s behavior. For example, the Java programming language has an important interface built into it, called Cloneable. (This interface is discussed in detail in Section 6.1.9, “Object Cloning,” on p. 330.) If your class implements Cloneable, the clone method in the Object class will make an exact copy of your class’s objects. If you want both cloneability and comparability, simply implement both interfaces. Use commas to separate the interfaces that you want to implement:

class Employee implements Cloneable, Comparable

![]() NOTE:

NOTE:

Records and enumeration classes cannot extend other classes (since they implicitly extend the Record and Enum class). However, they can implement interfaces.

![]() NOTE:

NOTE:

Interfaces can be sealed. As with sealed classes, the direct subtypes (which can be classes or interfaces) must be declared in a permits clause or be located in the same source file.

6.1.3 Interfaces and Abstract Classes

If you read the section about abstract classes in Chapter 5, you may wonder why the designers of the Java programming language bothered with introducing the concept of interfaces. Why can’t Comparable simply be an abstract class:

abstract class Comparable // why not?

{

public abstract int compareTo(Object other);

}

The Employee class would then simply extend this abstract class and supply the compareTo method:

class Employee extends Comparable // why not?

{

public int compareTo(Object other) { . . . }

}

There is, unfortunately, a major problem with using an abstract base class to express a generic property. A class can only extend a single class. Suppose the Employee class already extends a different class, say, Person. Then it can’t extend a second class.

class Employee extends Person, Comparable // ERROR

But each class can implement as many interfaces as it likes:

class Employee extends Person implements Comparable // OK

Other programming languages, in particular C++, allow a class to have more than one superclass. This feature is called multiple inheritance. The designers of Java chose not to support multiple inheritance, because it makes the language either very complex (as in C++) or less efficient (as in Eiffel).

Instead, interfaces afford most of the benefits of multiple inheritance while avoiding the complexities and inefficiencies.

![]() C++ NOTE:

C++ NOTE:

C++ has multiple inheritance and all the complications that come with it, such as virtual base classes, dominance rules, and transverse pointer casts. Few C++ programmers use multiple inheritance, and some say it should never be used. Other programmers recommend using multiple inheritance only for the “mix-in” style of inheritance. In the mix-in style, a primary base class describes the parent object, and additional base classes (the so-called mix-ins) may supply auxiliary characteristics. That style is similar to a Java class with a single superclass and additional interfaces.

![]() TIP:

TIP:

You have seen the CharSequence interface in chapter 3. Both String and StringBuilder (as well as a few more esoteric string-like classes) implement this interface. The interface contains methods that are common to all classes that manage sequences of characters. A common interface encourages programmers to write methods that use the CharSequence interface. Those methods work with instances of String, StringBuilder, and the other string-like classes.

Sadly, the CharSequence interface is rather paltry. You can get the length, iterate over the code points or code units, extract subsequences, and lexicographically compare two sequences. Java 17 adds an isEmpty method.

If you process strings, and those operations suffice for your tasks, accept CharSequence instances instead of strings.

6.1.4 Static and Private Methods

As of Java 8, you are allowed to add static methods to interfaces. There was never a technical reason why this should be outlawed. It simply seemed to be against the spirit of interfaces as abstract specifications.

Up to now, it has been common to place static methods in companion classes. In the standard library, you’ll find pairs of interfaces and utility classes such as Collection/Collections or Path/Paths.

You can construct a path to a file or directory from a URI, or from a sequence of strings, such as Paths.get("jdk-17", "conf", "security"). In Java 11, equivalent methods are provided in the Path interface:

public interface Path

{

public static Path of(URI uri) { . . . }

public static Path of(String first, String... more) { . . . }

. . .

}

Then the Paths class is no longer necessary.

Similarly, when you implement your own interfaces, there is no longer a reason to provide a separate companion class for utility methods.

As of Java 9, methods in an interface can be private. A private method can be static or an instance method. Since private methods can only be used in the methods of the interface itself, their use is limited to being helper methods for the other methods of the interface.

6.1.5 Default Methods

You can supply a default implementation for any interface method. You must tag such a method with the default modifier.

public interface Comparable<T>

{

default int compareTo(T other) { return 0; }

// by default, all elements are the same

}

Of course, that is not very useful since every realistic implementation of Comparable would override this method. But there are other situations where default methods can be useful. For example, in Chapter 9 you will see an Iterator interface for visiting elements in a data structure. It declares a remove method as follows:

public interface Iterator<E>

{

boolean hasNext();

E next();

default void remove() { throw new UnsupportedOperationException("remove"); }

. . .

}

If you implement an iterator, you need to provide the hasNext and next methods. There are no defaults for these methods—they depend on the data structure that you are traversing. But if your iterator is read-only, you don’t have to worry about the remove method.

A default method can call other methods. For example, a Collection interface can define a convenience method

public interface Collection

{

int size(); // an abstract method

default boolean isEmpty() { return size() == 0; }

. . .

}

Then a programmer implementing Collection doesn’t have to worry about implementing an isEmpty method.

![]() NOTE:

NOTE:

The Collection interface in the Java API does not actually do this. Instead, there is a class AbstractCollection that implements Collection and defines isEmpty in terms of size. Implementors of a collection are advised to extend AbstractCollection. That technique is obsolete. Just implement the methods in the interface.

An important use for default methods is interface evolution. Consider, for example, the Collection interface that has been a part of Java for many years. Suppose that a long time ago, you provided a class

public class Bag implements Collection

Later, in Java 8, a stream method was added to the interface.

Suppose the stream method was not a default method. Then the Bag class would no longer compile since it doesn’t implement the new method. Adding a nondefault method to an interface is not source-compatible.

But suppose you don’t recompile the class and simply use an old JAR file containing it. The class will still load, even with the missing method. Programs can still construct Bag instances, and nothing bad will happen. (Adding a method to an interface is binary compatible.) However, if a program calls the stream method on a Bag instance, an AbstractMethodError occurs.

Making the method a default method solves both problems. The Bag class will again compile. And if the class is loaded without being recompiled and the stream method is invoked on a Bag instance, the Collection.stream method is called.

6.1.6 Resolving Default Method Conflicts

What happens if the exact same method is defined as a default method in one interface and then again as a method of a superclass or another interface? Languages such as Scala and C++ have complex rules for resolving such ambiguities. Fortunately, the rules in Java are much simpler. Here they are:

1. Superclasses win. If a superclass provides a concrete method, default methods with the same name and parameter types are simply ignored.

2. Interfaces clash. If an interface provides a default method, and another interface contains a method with the same name and parameter types (default or not), then you must resolve the conflict by overriding that method.

Let’s look at the second rule. Consider two interfaces with a getName method:

interface Person

{

default String getName() { return ""; };

}

interface Named

{

default String getName() { return getClass().getName() + "_" + hashCode(); }

}

What happens if you form a class that implements both of them?

class Student implements Person, Named { . . . }

The class inherits two inconsistent getName methods provided by the Person and Named interfaces. Instead of choosing one over the other, the Java compiler reports an error and leaves it up to the programmer to resolve the ambiguity. Simply provide a getName method in the Student class. In that method, you can choose one of the two conflicting methods, like this:

class Student implements Person, Named

{

public String getName() { return Person.super.getName(); }

. . .

}

Now assume that the Named interface does not provide a default implementation for getName:

interface Named

{

String getName();

}

Can the Student class inherit the default method from the Person interface? This might be reasonable, but the Java designers decided in favor of uniformity. It doesn’t matter how two interfaces conflict. If at least one interface provides an implementation, the compiler reports an error, and the programmer must resolve the ambiguity.

![]() NOTE:

NOTE:

Of course, if neither interface provides a default for a shared method, then we are in the situation before Java 8, and there is no conflict. An implementing class has two choices: implement the method, or leave it unimplemented. In the latter case, the class is itself abstract.

We just discussed name clashes between two interfaces. Now consider a class that extends a superclass and implements an interface, inheriting the same method from both. For example, suppose that Person is a class and Student is defined as

class Student extends Person implements Named { . . . }

In that case, only the superclass method matters, and any default method from the interface is simply ignored. In our example, Student inherits the getName method from Person, and it doesn’t make any difference whether the Named interface provides a default for getName or not. This is the “class wins” rule.

The “class wins” rule ensures compatibility with Java 7. If you add default methods to an interface, it has no effect on code that worked before there were default methods.

![]() CAUTION:

CAUTION:

You can never make a default method that redefines one of the methods in the Object class. For example, you can’t define a default method for toString or equals, even though that might be attractive for interfaces such as List. As a consequence of the “class wins” rule, such a method could never win against Object.toString or Object.equals.

6.1.7 Interfaces and Callbacks

A common pattern in programming is the callback pattern. In this pattern, you specify the action that should occur whenever a particular event happens. For example, you may want a particular action to occur when a button is clicked or a menu item is selected. However, as you have not yet seen how to implement user interfaces, we will consider a similar but simpler situation.

The javax.swing package contains a Timer class that is useful if you want to be notified whenever a time interval has elapsed. For example, if a part of your program contains a clock, you can ask to be notified every second so that you can update the clock face.

When you construct a timer, you set the time interval and tell it what it should do whenever the time interval has elapsed.

How do you tell the timer what it should do? In many programming languages, you supply the name of a function that the timer should call periodically. However, the classes in the Java standard library take an object-oriented approach. You pass an object of some class. The timer then calls one of the methods on that object. Passing an object is more flexible than passing a function because the object can carry additional information.

Of course, the timer needs to know what method to call. The timer requires that you specify an object of a class that implements the ActionListener interface of the java.awt.event package. Here is that interface:

public interface ActionListener

{

void actionPerformed(ActionEvent event);

}

The timer calls the actionPerformed method when the time interval has expired.

Suppose you want to print a message “At the tone, the time is . . .”, followed by a beep, once every second. You would define a class that implements the ActionListener interface. You would then place whatever statements you want to have executed inside the actionPerformed method.

class TimePrinter implements ActionListener

{

public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent event)

{

System.out.println("At the tone, the time is "

+ Instant.ofEpochMilli(event.getWhen()));

Toolkit.getDefaultToolkit().beep();

}

}

Note the ActionEvent parameter of the actionPerformed method. This parameter gives information about the event, such as the time when the event happened. The call event.getWhen() returns the event time, measured in milliseconds since the “epoch” (January 1, 1970). By passing it to the static Instant.ofEpochMilli method, we get a more readable description.

Next, construct an object of this class and pass it to the Timer constructor.

var listener = new TimePrinter(); Timer t = new Timer(1000, listener);

The first parameter of the Timer constructor is the time interval that must elapse between notifications, measured in milliseconds. We want to be notified every second. The second parameter is the listener object.

Finally, start the timer.

t.start();

Every second, a message like

At the tone, the time is 2017-12-16T05:01:49.550Z

is displayed, followed by a beep.

![]() CAUTION:

CAUTION:

Be sure to import javax.swing.Timer. There is also a java.util.Timer class that is slightly different.

Listing 6.3 puts the timer and its action listener to work. After the timer is started, the program puts up a message dialog and waits for the user to click the OK button to stop. While the program waits for the user, the current time is displayed every second. (If you omit the dialog, the program would terminate as soon as the main method exits.)

Listing 6.3 timer/TimerTest.java

1 package timer;

2

3 /**

4 @version 1.02 2017-12-14

5 @author Cay Horstmann

6 */

7

8 import java.awt.*;

9 import java.awt.event.*;

10 import java.time.*;

11 import javax.swing.*;

12

13 public class TimerTest

14 {

15 public static void main(String[] args)

16 {

17 var listener = new TimePrinter();

18

19 // construct a timer that calls the listener once every second

20 var timer = new Timer(1000, listener);

21 timer.start();

22

23 // keep program running until the user selects "OK"

24 JOptionPane.showMessageDialog(null, "Quit program?");

25 System.exit(0);

26 }

27 }

28

29 class TimePrinter implements ActionListener

30 {

31 public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent event)

32 {

33 System.out.println("At the tone, the time is " + Instant.ofEpochMilli(event.getWhen()));

34 Toolkit.getDefaultToolkit().beep();

35 }

36 }

6.1.8 The Comparator Interface

In Section 6.1.1, “The Interface Concept,” on p. 312, you have seen how you can sort an array of objects, provided they are instances of classes that implement the Comparable interface. For example, you can sort an array of strings since the String class implements Comparable<String>, and the String.compareTo method compares strings in dictionary order.

Now suppose we want to sort strings by increasing length, not in dictionary order. We can’t have the String class implement the compareTo method in two ways—and at any rate, the String class isn’t ours to modify.

To deal with this situation, there is a second version of the Arrays.sort method whose parameters are an array and a comparator—an instance of a class that implements the Comparator interface.

public interface Comparator<T>

{

int compare(T first, T second);

}

To compare strings by length, define a class that implements Comparator<String>:

class LengthComparator implements Comparator<String>

{

public int compare(String first, String second)

{

return first.length() - second.length();

}

}

To actually do the comparison, you need to make an instance:

var comp = new LengthComparator(); if (comp.compare(words[i], words[j]) > 0) . . .

Contrast this call with words[i].compareTo(words[j]). The compare method is called on the comparator object, not the string itself.

![]() NOTE:

NOTE:

Even though the LengthComparator object has no state, you still need to make an instance of it. You need the instance to call the compare method—it is not a static method.

To sort an array, pass a LengthComparator object to the Arrays.sort method:

String[] friends = { "Peter", "Paul", "Mary" };

Arrays.sort(friends, new LengthComparator());

Now the array is either ["Paul", "Mary", "Peter"] or ["Mary", "Paul", "Peter"].

You will see in Section 6.2, “Lambda Expressions,” on p. 338 how to use a Comparator much more easily with a lambda expression.

6.1.9 Object Cloning

In this section, we discuss the Cloneable interface that indicates that a class has provided a safe clone method. Since cloning is not all that common, and the details are quite technical, you may just want to glance at this material until you need it.

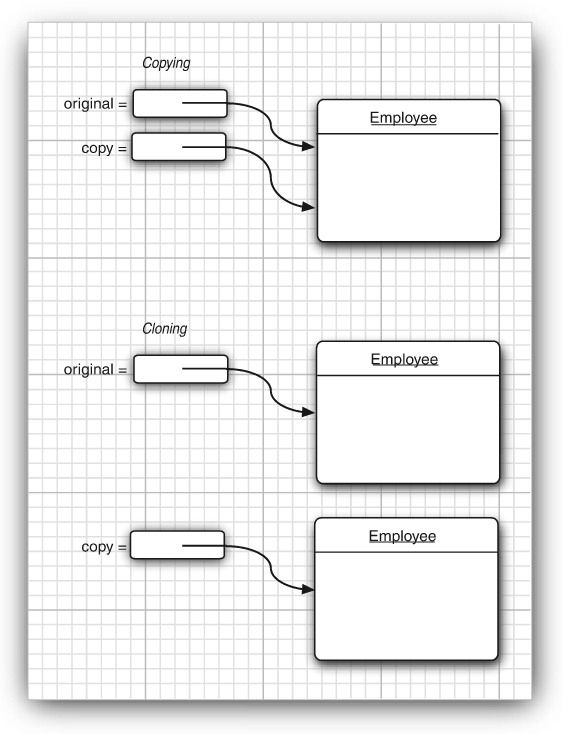

To understand what cloning means, recall what happens when you make a copy of a variable holding an object reference. The original and the copy are references to the same object (see Figure 6.1). This means a change to either variable also affects the other.

var original = new Employee("John Public", 50000);

Employee copy = original;

copy.raiseSalary(10); // oops--also changed original

Figure 6.1 Copying and cloning

If you would like copy to be a new object that begins its life being identical to original but whose state can diverge over time, use the clone method.

Employee copy = original.clone(); copy.raiseSalary(10); // OK--original unchanged

But it isn’t quite so simple. The clone method is a protected method of Object, which means that your code cannot simply call it. Only the Employee class can clone Employee objects. There is a reason for this restriction. Think about the way in which the Object class can implement clone. It knows nothing about the object at all, so it can make only a field-by-field copy. If all instance fields in the object are numbers or other basic types, copying the fields is just fine. But if the object contains references to subobjects, then copying the field gives you another reference to the same subobject, so the original and the cloned objects still share some information.

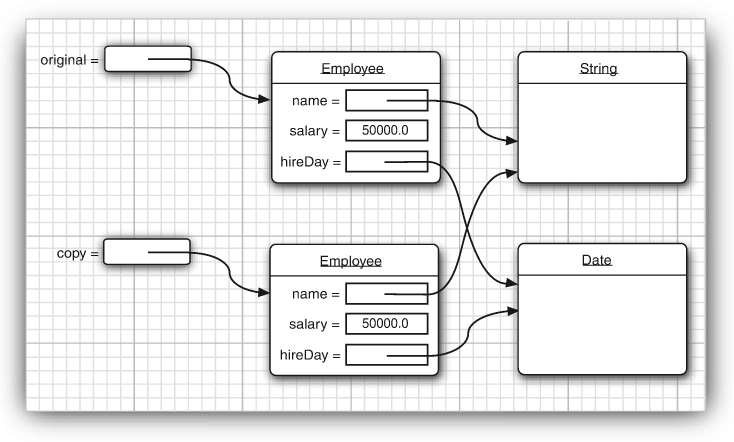

To visualize that, consider the Employee class that was introduced in Chapter 4. Figure 6.2 shows what happens when you use the clone method of the Object class to clone such an Employee object. As you can see, the default cloning operation is “shallow”—it doesn’t clone objects that are referenced inside other objects. (The figure shows a shared Date object. For reasons that will become clear shortly, this example uses a version of the Employee class in which the hire day is represented as a Date.)

Figure 6.2 A shallow copy

Does it matter if the copy is shallow? It depends. If the subobject shared between the original and the shallow clone is immutable, then the sharing is safe. This certainly happens if the subobject belongs to an immutable class, such as String. Alternatively, the subobject may simply remain constant throughout the lifetime of the object, with no mutators touching it and no methods yielding a reference to it.

Quite frequently, however, subobjects are mutable, and you must redefine the clone method to make a deep copy that clones the subobjects as well. In our example, the hireDay field is a Date, which is mutable, so it too must be cloned. (For that reason, this example uses a field of type Date, not LocalDate, to demonstrate the cloning process. Had hireDay been an instance of the immutable LocalDate class, no further action would have been required.)

For every class, you need to decide whether

1. The default clone method is good enough;

2. The default clone method can be patched up by calling clone on the mutable subobjects; or

3. clone should not be attempted.

The third option is actually the default. To choose either the first or the second option, a class must

1. Implement the Cloneable interface; and

2. Redefine the clone method with the public access modifier.

![]() NOTE:

NOTE:

The clone method is declared protected in the Object class, so that your code can’t simply call anObject.clone(). But aren’t protected methods accessible from any subclass, and isn’t every class a subclass of Object? Fortunately, the rules for protected access are more subtle (see Chapter 5). A subclass can call a protected clone method only to clone its own objects. You must redefine clone to be public to allow objects to be cloned by any method.

In this case, the appearance of the Cloneable interface has nothing to do with the normal use of interfaces. In particular, it does not specify the clone method—that method is inherited from the Object class. The interface merely serves as a tag, indicating that the class designer understands the cloning process. Objects are so paranoid about cloning that they generate a checked exception if an object requests cloning but does not implement that interface.

![]() NOTE:

NOTE:

The Cloneable interface is one of a handful of tagging interfaces that Java provides. (Some programmers call them marker interfaces.) Recall that the usual purpose of an interface such as Comparable is to ensure that a class implements a particular method or set of methods. A tagging interface has no methods; its only purpose is to allow the use of instanceof in a type inquiry:

if (obj instanceof Cloneable) . . .

I recommend that you do not use tagging interfaces in your own programs.

Even if the default (shallow copy) implementation of clone is adequate, you still need to implement the Cloneable interface, redefine clone to be public, and call super.clone(). Here is an example:

class Employee implements Cloneable

{

// public access, change return type

public Employee clone() throws CloneNotSupportedException

{

return (Employee) super.clone();

}

. . .

}

![]() NOTE:

NOTE:

Up to Java 1.4, the clone method always had return type Object. Nowadays, you can specify the correct return type for your clone methods. This is an example of covariant return types (see Chapter 5).

The clone method that you just saw adds no functionality to the shallow copy provided by Object.clone. It merely makes the method public. To make a deep copy, you have to work harder and clone the mutable instance fields.

Here is an example of a clone method that creates a deep copy:

class Employee implements Cloneable

{

. . .

public Employee clone() throws CloneNotSupportedException

{

// call Object.clone()

Employee cloned = (Employee) super.clone();

// clone mutable fields

cloned.hireDay = (Date) hireDay.clone();

return cloned;

} }

The clone method of the Object class threatens to throw a CloneNotSupportedException—it does that whenever clone is invoked on an object whose class does not implement the Cloneable interface. Of course, the Employee and Date classes implement the Cloneable interface, so the exception won’t be thrown. However, the compiler does not know that. Therefore, we declared the exception:

public Employee clone() throws CloneNotSupportedException

![]() NOTE:

NOTE:

Would it be better to catch the exception instead? (See Chapter 7 for details on catching exceptions.)

public Employee clone()

{

try

{

Employee cloned = (Employee) super.clone();

. . .

}

catch (CloneNotSupportedException e) { return null; }

// this won't happen, since we are Cloneable

}

This is appropriate for final classes. Otherwise, it is better to leave the throws specifier in place. That gives subclasses the option of throwing a CloneNotSupportedException if they can’t support cloning.

You have to be careful about cloning of subclasses. For example, once you have defined the clone method for the Employee class, anyone can use it to clone Manager objects. Can the Employee clone method do the job? It depends on the fields of the Manager class. In our case, there is no problem because the bonus field has primitive type. But Manager might have acquired fields that require a deep copy or are not cloneable. There is no guarantee that the implementor of the subclass has fixed clone to do the right thing. For that reason, the clone method is declared as protected in the Object class. But you don’t have that luxury if you want the users of your classes to invoke clone.

Should you implement clone in your own classes? If your clients need to make deep copies, then you probably should. Some authors feel that you should avoid clone altogether and instead implement another method for the same purpose. I agree that clone is rather awkward, but you’ll run into the same issues if you shift the responsibility to another method. At any rate, cloning is less common than you may think. Less than 5 percent of the classes in the standard library implement clone.

The program in Listing 6.4 clones an instance of the class Employee (Listing 6.5), then invokes two mutators. The raiseSalary method changes the value of the salary field, whereas the setHireDay method changes the state of the hireDay field. Neither mutation affects the original object because clone has been defined to make a deep copy.

![]() NOTE:

NOTE:

All array types have a clone method that is public, not protected. You can use it to make a new array that contains copies of all elements. For example:

int[] luckyNumbers = { 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13 };

int[] cloned = luckyNumbers.clone();

cloned[5] = 12; // doesn't change luckyNumbers[5]

![]() NOTE:

NOTE:

Chapter 2 of Volume II shows an alternate mechanism for cloning objects, using the object serialization feature of Java. That mechanism is easy to implement and safe, but not very efficient.

Listing 6.4 clone/CloneTest.java

1 package clone;

2

3 /**

4 * This program demonstrates cloning.

5 * @version 1.11 2018-03-16

6 * @author Cay Horstmann

7 */

8 public class CloneTest

9 {

10 public static void main(String[] args) throws CloneNotSupportedException

11 {

12 var original = new Employee("John Q. Public", 50000);

13 original.setHireDay(2000, 1, 1);

14 Employee copy = original.clone();

15 copy.raiseSalary(10);

16 copy.setHireDay(2002, 12, 31);

17 System.out.println("original=" + original);

18 System.out.println("copy=" + copy);

19 }

20 }

Listing 6.5 clone/Employee.java

1 package clone;

2

3 import java.util.Date;

4 import java.util.GregorianCalendar;

5

6 public class Employee implements Cloneable

7 {

8 private String name;

9 private double salary;

10 private Date hireDay;

11

12 public Employee(String name, double salary)

13 {

14 this.name = name;

15 this.salary = salary;

16 hireDay = new Date();

17 }

18

19 public Employee clone() throws CloneNotSupportedException

20 {

21 // call Object.clone()

22 Employee cloned = (Employee) super.clone();

23

24 // clone mutable fields

25 cloned.hireDay = (Date) hireDay.clone();

26

27 return cloned;

28 }

29

30 /**

31 * Set the hire day to a given date.

32 * @param year the year of the hire day

33 * @param month the month of the hire day

34 * @param day the day of the hire day

35 */

36 public void setHireDay(int year, int month, int day)

37 {

38 Date newHireDay = new GregorianCalendar(year, month - 1, day).getTime();

39

40 // example of instance field mutation

41 hireDay.setTime(newHireDay.getTime());

42 }

43

44 public void raiseSalary(double byPercent)

45 {

46 double raise = salary * byPercent / 100;

47 salary += raise;

48 }

49

50 public String toString()

51 {

52 return "Employee[name=" + name + ",salary=" + salary + ",hireDay=" + hireDay + "]";

53 }

54 }

6.2 Lambda Expressions

In the following sections, you will learn how to use lambda expressions for defining blocks of code with a concise syntax, and how to write code that consumes lambda expressions.

6.2.1 Why Lambdas?

A lambda expression is a block of code that you can pass around so it can be executed later, once or multiple times. Before getting into the syntax (or even the curious name), let’s step back and observe where we have used such code blocks in Java.

In Section 6.1.7, “Interfaces and Callbacks,” on p. 326, you saw how to do work in timed intervals. Put the work into the actionPerformed method of an ActionListener:

class Worker implements ActionListener

{

public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent event)

{

// do some work

}

}

Then, when you want to repeatedly execute this code, you construct an instance of the Worker class. You then submit the instance to a Timer object.

The key point is that the actionPerformed method contains code that you want to execute later.

Or consider sorting with a custom comparator. If you want to sort strings by length instead of the default dictionary order, you can pass a Comparator object to the sort method:

class LengthComparator implements Comparator<String>

{

public int compare(String first, String second)

{

return first.length() - second.length();

}

}

. . .

Arrays.sort(strings, new LengthComparator());

The compare method isn’t called right away. Instead, the sort method keeps calling the compare method, rearranging the elements if they are out of order, until the array is sorted. You give the sort method a snippet of code needed to compare elements, and that code is integrated into the rest of the sorting logic, which you’d probably not care to reimplement.

Both examples have something in common. A block of code was passed to someone—a timer, or a sort method. That code block was called at some later time.

Up to now, giving someone a block of code hasn’t been easy in Java. You couldn’t just pass code blocks around. Java is an object-oriented language, so you had to construct an object belonging to a class that has a method with the desired code.

In other languages, it is possible to work with blocks of code directly. The Java designers have resisted adding this feature for a long time. After all, a great strength of Java is its simplicity and consistency. A language can become an unmaintainable mess if it includes every feature that yields marginally more concise code. However, in those other languages it isn’t just easier to spawn a thread or to register a button click handler; large swaths of their APIs are simpler, more consistent, and more powerful. In Java, one could have written similar APIs taking objects of classes that implement a particular interface, but such APIs would be unpleasant to use.

For some time, the question was not whether to augment Java for functional programming, but how to do it. It took several years of experimentation before a design emerged that is a good fit for Java. In the next section, you will see how you can work with blocks of code in Java.

6.2.2 The Syntax of Lambda Expressions

Consider again the sorting example from the preceding section. We pass code that checks whether one string is shorter than another. We compute

first.length() - second.length()

What are first and second? They are both strings. Java is a strongly typed language, and we must specify that as well:

(String first, String second) -> first.length() - second.length()

You have just seen your first lambda expression. Such an expression is simply a block of code, together with the specification of any variables that must be passed to the code.

Why the name? Many years ago, before there were any computers, the logician Alonzo Church wanted to formalize what it means for a mathematical function to be effectively computable. (Curiously, there are functions that are known to exist, but nobody knows how to compute their values.) He used the Greek letter lambda (λ) to mark parameters. Had he known about the Java API, he would have written

λfirst.λsecond.first.length() - second.length()

![]() NOTE:

NOTE:

Why the letter λ? Did Church run out of other letters of the alphabet? Actually, the venerable Principia Mathematica used the ^ accent to denote free variables, which inspired Church to use an uppercase lambda ᴧ for parameters. But in the end, he switched to the lowercase version. Ever since, an expression with parameter variables has been called a lambda expression.

What you have just seen is a simple form of lambda expressions in Java: parameters, the -> arrow, and an expression. If the code carries out a computation that doesn’t fit in a single expression, write it exactly like you would have written a method: enclosed in {} and with explicit return statements. For example,

(String first, String second) ->

{

if (first.length() < second.length()) return -1;

else if (first.length() > second.length()) return 1;

else return 0;

}

If a lambda expression has no parameters, you still supply empty parentheses, just as with a parameterless method:

() -> { for (int i = 100; i >= 0; i--) System.out.println(i); }

If the parameter types of a lambda expression can be inferred, you can omit them. For example,

Comparator<String> comp = (first, second) // same as (String first, String second) -> first.length() - second.length();

Here, the compiler can deduce that first and second must be strings because the lambda expression is assigned to a string comparator. (We will have a closer look at this assignment in the next section.)

If a method has a single parameter with inferred type, you can even omit the parentheses:

ActionListener listener = event ->

System.out.println("The time is "

+ Instant.ofEpochMilli(event.getWhen()));

// instead of (event) -> . . . or (ActionEvent event) -> . . .

You never specify the result type of a lambda expression. It is always inferred from context. For example, the expression

(String first, String second) -> first.length() - second.length()

can be used in a context where a result of type int is expected.

Finally, you can use var to denote an inferred type. This isn’t common. The syntax was invented for attaching annotations (see Chapter 8 of Volume II):

(@NonNull var first, @NonNull var second) -> first.length() - second.length()

![]() NOTE:

NOTE:

It is illegal for a lambda expression to return a value in some branches but not in others. For example, (int x) -> { if (x >= 0) return 1; } is invalid.

The program in Listing 6.6 shows how to use lambda expressions for a comparator and an action listener.

Listing 6.6 lambda/LambdaTest.java

1 package lambda;

2

3 import java.util.*;

4 import javax.swing.*;

5 import javax.swing.Timer;

6

7 /**

8 * This program demonstrates the use of lambda expressions.

9 * @version 1.0 2015-05-12

10 * @author Cay Horstmann

11 */

12 public class LambdaTest

13 {

14 public static void main(String[] args)

15 {

16 var planets = new String[] { "Mercury", "Venus", "Earth", "Mars",

17 "Jupiter", "Saturn", "Uranus", "Neptune" };

18 System.out.println(Arrays.toString(planets));

19 System.out.println("Sorted in dictionary order:");

20 Arrays.sort(planets);

21 System.out.println(Arrays.toString(planets));

22 System.out.println("Sorted by length:");

23 Arrays.sort(planets, (first, second) -> first.length() - second.length());

24 System.out.println(Arrays.toString(planets));

25

26 var timer = new Timer(1000, event ->

27 System.out.println("The time is " + new Date()));

28 timer.start();

29

30 // keep program running until user selects "OK"

31 JOptionPane.showMessageDialog(null, "Quit program?");

32 System.exit(0);

33 }

34 }

6.2.3 Functional Interfaces

As we discussed, there are many existing interfaces in Java that encapsulate blocks of code, such as ActionListener or Comparator. Lambdas are compatible with these interfaces.

You can supply a lambda expression whenever an object of an interface with a single abstract method is expected. Such an interface is called a functional interface.

![]() NOTE:

NOTE:

You may wonder why a functional interface must have a single abstract method. Aren’t all methods in an interface abstract? Actually, it has always been possible for an interface to redeclare methods from the Object class such as toString or clone, and these declarations do not make the methods abstract. (Some interfaces in the Java API redeclare Object methods in order to attach javadoc comments. Check out the Comparator API for an example.) More importantly, as you saw in Section 6.1.5, “Default Methods,” on p. 323, interfaces can declare nonabstract methods.

To demonstrate the conversion to a functional interface, consider the Arrays.sort method. Its second parameter requires an instance of Comparator, an interface with a single method. Simply supply a lambda:

Arrays.sort(words, (first, second) -> first.length() - second.length());

Behind the scenes, the Arrays.sort method receives an object of some class that implements Comparator<String>. Invoking the compare method on that object executes the body of the lambda expression. The management of these objects and classes is completely implementation-dependent, and it can be much more efficient than using traditional inner classes. It is best to think of a lambda expression as a function, not an object, and to accept that it can be passed to a functional interface.

This conversion to interfaces is what makes lambda expressions so compelling. The syntax is short and simple. Here is another example:

var timer = new Timer(1000, event ->

{

System.out.println("At the tone, the time is "

+ Instant.ofEpochMilli(event.getWhen()));

Toolkit.getDefaultToolkit().beep();

});

That’s a lot easier to read than the alternative with a class that implements the ActionListener interface.

In fact, conversion to a functional interface is the only thing that you can do with a lambda expression in Java. In other programming languages that support function literals, you can declare function types such as (String, String) -> int, declare variables of those types, and use the variables to save function expressions. However, the Java designers decided to stick with the familiar concept of interfaces instead of adding function types to the language.

![]() NOTE:

NOTE:

You can’t even assign a lambda expression to a variable of type Object—Object is not a functional interface.

The Java API defines a number of very generic functional interfaces in the java.util.function package. One of the interfaces, BiFunction<T, U, R>, describes functions with parameter types T and U and return type R. You can save your string comparison lambda in a variable of that type:

BiFunction<String, String, Integer> comp = (first, second) -> first.length() - second.length();

However, that does not help you with sorting. There is no Arrays.sort method that wants a BiFunction. If you have used a functional programming language before, you may find this curious. But for Java programmers, it’s pretty natural. An interface such as Comparator has a specific purpose, not just a method with given parameter and return types. When you want to do something with lambda expressions, you still want to keep the purpose of the expression in mind, and have a specific functional interface for it.

A particularly useful interface in the java.util.function package is Predicate:

public interface Predicate<T>

{

boolean test(T t);

// additional default and static methods

}

The ArrayList class has a removeIf method whose parameter is a Predicate. It is specifically designed to pass a lambda expression. For example, the following statement removes all null values from an array list:

list.removeIf(e -> e == null);

Another useful functional interface is Supplier<T>:

public interface Supplier<T>

{

T get();

}

A supplier has no arguments and yields a value of type T when it is called. Suppliers are used for lazy evaluation. For example, consider the call

LocalDate hireDay = Objects.requireNonNullElse(day, new LocalDate.of(1970, 1, 1));

This is not optimal. We expect that day is rarely null, so we only want to construct the default LocalDate when necessary. By using the supplier, we can defer the computation:

LocalDate hireDay = Objects.requireNonNullElseGet(day, () -> new LocalDate.of(1970, 1, 1));

The requireNonNullElseGet method only calls the supplier when the value is needed.

6.2.4 Method References

Sometimes, a lambda expression involves a single method. For example, suppose you simply want to print the event object whenever a timer event occurs. Of course, you could call

var timer = new Timer(1000, event -> System.out.println(event));

It would be nicer if you could just pass the println method to the Timer constructor. Here is how you do that:

var timer = new Timer(1000, System.out::println);

The expression System.out::println is a method reference. It directs the compiler to produce an instance of a functional interface, overriding the single abstract method of the interface to call the given method. In this example, an ActionListener is produced whose actionPerformed(ActionEvent e) method calls System.out.println(e).

![]() NOTE:

NOTE:

Like a lambda expression, a method reference is not an object. It gives rise to an object when assigned to a variable whose type is a functional interface.

![]() NOTE:

NOTE:

There are ten overloaded println methods in the PrintStream class (of which System.out is an instance). The compiler needs to figure out which one to use, depending on context. In our example, the method reference System.out::println must be turned into an ActionListener instance with a method

void actionPerformed(ActionEvent e)

The println(Object x) method is selected from the ten overloaded println methods since Object is the best match for ActionEvent. When the actionPerformed method is called, the event object is printed.

Now suppose we assign the same method reference to a different functional interface:

Runnable task = System.out::println;

The Runnable functional interface has a single abstract method with no parameters

void run()

In this case, the println() method with no parameters is chosen. Calling task.run() prints a blank line to System.out.

As another example, suppose you want to sort strings regardless of letter case. You can pass this method expression:

Arrays.sort(strings, String::compareToIgnoreCase)

As you can see from these examples, the :: operator separates the method name from the name of an object or class. There are three variants:

Chapter 6 Interfaces, Lambda Expressions, and Inner Classes 346

1. object::instanceMethod

2. Class::instanceMethod

3. Class::staticMethod

In the first variant, the method reference is equivalent to a lambda expression whose parameters are passed to the method. In the case of System.out::println, the object is System.out, and the method expression is equivalent to x -> System.out.println(x).

In the second variant, the first parameter becomes the implicit parameter of the method. For example, String::compareToIgnoreCase is the same as (x, y) -> x.compareToIgnoreCase(y).

In the third variant, all parameters are passed to the static method: Math::pow is equivalent to (x, y) -> Math.pow(x, y).

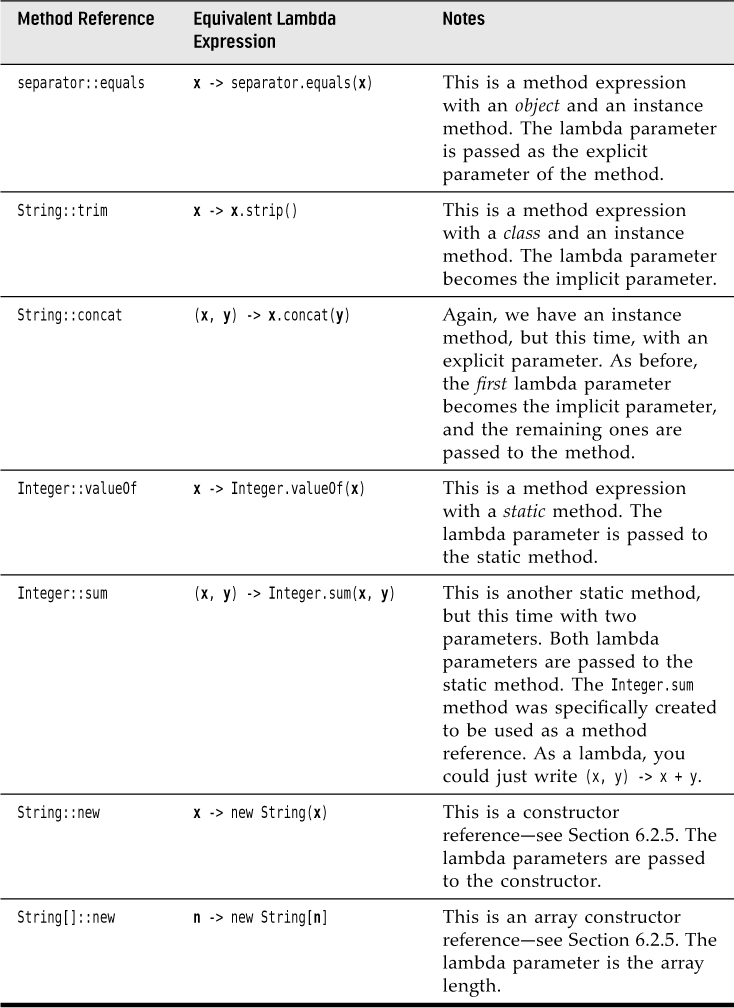

Table 6.1 walks you through additional examples.

Note that a lambda expression can only be rewritten as a method reference if the body of the lambda expression calls a single method and doesn’t do anything else. Consider the lambda expression

s -> s.length() == 0

There is a single method call. But there is also a comparison, so you can’t use a method reference here.

![]() NOTE:

NOTE:

When there are multiple overloaded methods with the same name, the compiler will try to find from the context which one you mean. For example, there are two versions of the Math.max method, one for integers and one for double values. Which one gets picked depends on the method parameters of the functional interface to which Math::max is converted. Just like lambda expressions, method references don’t live in isolation. They are always turned into instances of functional interfaces.

![]() NOTE:

NOTE:

Sometimes, the API contains methods that are specifically intended to be used as method references. For example, the Objects class has a method isNull to test whether an object reference is null. At first glance, this doesn’t seem useful because the test obj == null is easier to read than Objects.isNull(obj). But you can pass the method reference to any method with a Predicate parameter. For example, to remove all null references from a list, you can call

list.removeIf(Objects::isNull); // A bit easier to read than list.removeIf(e -> e == null);

Table 6.1 Method Reference Examples

![]() NOTE:

NOTE:

There is a tiny difference between a method reference with an object and its equivalent lambda expression. Consider a method reference such as separator::equals. If separator is null, forming separator::equals immediately throws a NullPointerException. The lambda expression x -> separator.equals(x) only throws a NullPointerException if it is invoked.

You can capture the this parameter in a method reference. For example, this::equals is the same as x -> this.equals(x). It is also valid to use super. The method expression

super::instanceMethod

uses this as the target and invokes the superclass version of the given method. Here is an artificial example that shows the mechanics:

class Greeter

{

public void greet(ActionEvent event)

{

System.out.println("Hello, the time is "

+ Instant.ofEpochMilli(event.getWhen()));

}

}

class RepeatedGreeter extends Greeter

{

public void greet(ActionEvent event)

{

var timer = new Timer(1000, super::greet);

timer.start();

}

}

When the RepeatedGreeter.greet method starts, a Timer is constructed that executes the super::greet method on every timer tick.

6.2.5 Constructor References

Constructor references are just like method references, except that the name of the method is new. For example, Person::new is a reference to a Person constructor. Which constructor? It depends on the context. Suppose you have a list of strings. Then you can turn it into an array of Person objects, by calling the constructor on each of the strings, with the following invocation:

ArrayList<String> names = . . .; Stream<Person> stream = names.stream().map(Person::new); List<Person> people = stream.toList();

We will discuss the details of the stream, map, and toList methods in Chapter 1 of Volume II. For now, what’s important is that the map method calls the Person(String) constructor for each list element. If there are multiple Person constructors, the compiler picks the one with a String parameter because it infers from the context that the constructor is called with a string.

You can form constructor references with array types. For example, int[]::new is a constructor reference with one parameter: the length of the array. It is equivalent to the lambda expression n -> new int[n].

Array constructor references are useful to overcome a limitation of Java. As you will see in Chapter 8, it is not possible to construct an array of a generic type T. (The expression new T[n] is an error since it would be “erased” to new Object[n]). That is a problem for library authors. For example, suppose we want to have an array of Person objects. The Stream interface has a toArray method that returns an Object array:

Object[] people = stream.toArray();

But that is unsatisfactory. The user wants an array of references to Person, not references to Object. The stream library solves that problem with constructor references. Pass Person[]::new to the toArray method:

Person[] people = stream.toArray(Person[]::new);

The toArray method invokes this constructor to obtain an array of the correct type. Then it fills and returns the array.

6.2.6 Variable Scope

Often, you want to be able to access variables from an enclosing method or class in a lambda expression. Consider this example:

public static void repeatMessage(String text, int delay)

{

ActionListener listener = event ->

{

System.out.println(text);

Toolkit.getDefaultToolkit().beep();

};

new Timer(delay, listener).start();

}

Consider a call

repeatMessage("Hello", 1000); // prints Hello every 1,000 milliseconds

Now look at the variable text inside the lambda expression. Note that this variable is not defined in the lambda expression. Instead, it is a parameter variable of the repeatMessage method.

If you think about it, something nonobvious is going on here. The code of the lambda expression may run long after the call to repeatMessage has returned and the parameter variables are gone. How does the text variable stay around?

To understand what is happening, we need to refine our understanding of a lambda expression. A lambda expression has three ingredients:

1. A block of code

2. Parameters

3. Values for the free variables—that is, the variables that are not parameters and not defined inside the code

In our example, the lambda expression has one free variable, text. The data structure representing the lambda expression must store the values for the free variables—in our case, the string "Hello". We say that such values have been captured by the lambda expression. (It’s an implementation detail how that is done. For example, one can translate a lambda expression into an object with a single method, so that the values of the free variables are copied into instance variables of that object.)

![]() NOTE:

NOTE:

The technical term for a block of code together with the values of the free variables is a closure. If someone gloats that their language has closures, rest assured that Java has them as well. In Java, lambda expressions are closures.

As you have seen, a lambda expression can capture the value of a variable in the enclosing scope. In Java, to ensure that the captured value is well-defined, there is an important restriction. In a lambda expression, you can only reference variables whose value doesn’t change. For example, the following is illegal:

public static void countDown(int start, int delay)

{

ActionListener listener = event ->

{

start--; // ERROR: Can't mutate captured variable

System.out.println(start);

};

new Timer(delay, listener).start();

}

There is a reason for this restriction. Mutating variables in a lambda expression is not safe when multiple actions are executed concurrently. This won’t happen for the kinds of actions that we have seen so far, but in general, it is a serious problem. See Chapter 12 for more information on this important issue.

It is also illegal to refer, in a lambda expression, to a variable that is mutated outside. For example, the following is illegal:

public static void repeat(String text, int count)

{

for (int i = 1; i <= count; i++)

{

ActionListener listener = event ->

{

System.out.println(i + ": " + text);

// ERROR: Cannot refer to changing i

};

new Timer(1000, listener).start();

}

}

The rule is that any captured variable in a lambda expression must be effectively final. An effectively final variable is a variable that is never assigned a new value after it has been initialized. In our case, text always refers to the same String object, and it is OK to capture it. However, the value of i is mutated, and therefore i cannot be captured.

The body of a lambda expression has the same scope as a nested block. The same rules for name conflicts and shadowing apply. It is illegal to declare a parameter or a local variable in the lambda that has the same name as a local variable.

Path first = Path.of("/usr/bin");

Comparator<String> comp

= (first, second) -> first.length() - second.length();

// ERROR: Variable first already defined

Inside a method, you can’t have two local variables with the same name, and therefore, you can’t introduce such variables in a lambda expression either.

When you use the this keyword in a lambda expression, you refer to the this parameter of the method that creates the lambda. For example, consider

public class Application

{

public void init()

{

ActionListener listener = event ->

{

System.out.println(this.toString());

. . .

}

. . .

}

}

The expression this.toString() calls the toString method of the Application object, not the ActionListener instance. There is nothing special about the use of this in a lambda expression. The scope of the lambda expression is nested inside the init method, and this has the same meaning anywhere in that method.

6.2.7 Processing Lambda Expressions

Up to now, you have seen how to produce lambda expressions and pass them to a method that expects a functional interface. Now let us see how to write methods that can consume lambda expressions.

The point of using lambdas is deferred execution. After all, if you wanted to execute some code right now, you’d do that, without wrapping it inside a lambda. There are many reasons for executing code later, such as:

• Running the code in a separate thread

• Running the code multiple times

• Running the code at the right point in an algorithm (for example, the comparison operation in sorting)

• Running the code when something happens (a button was clicked, data has arrived, and so on)

• Running the code only when necessary

Let’s look at a simple example. Suppose you want to repeat an action n times. The action and the count are passed to a repeat method:

repeat(10, () -> System.out.println("Hello, World!"));

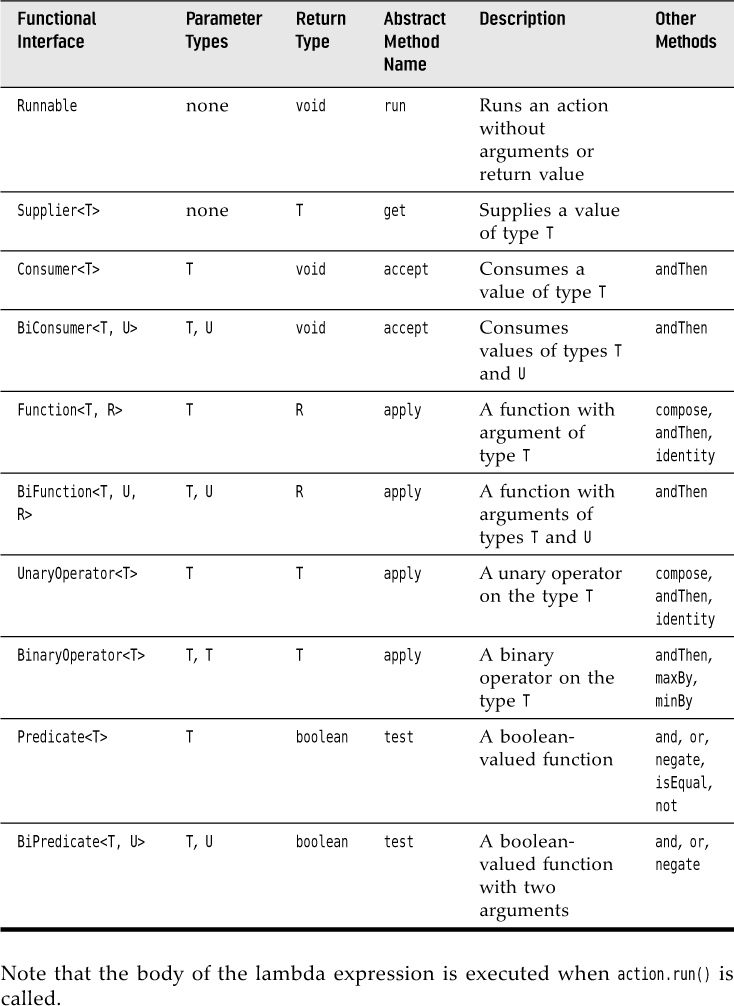

To accept the lambda, we need to pick (or, in rare cases, provide) a functional interface. Table 6.2 lists the most important functional interfaces that are provided in the Java API. In this case, we can use the Runnable interface:

public static void repeat(int n, Runnable action)

{

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) action.run();

}

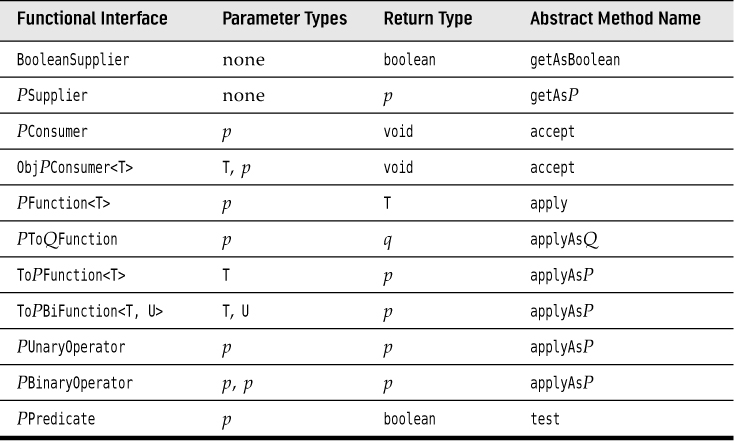

Table 6.2 Common Functional Interfaces

Now let’s make this example a bit more sophisticated. We want to tell the action in which iteration it occurs. For that, we need to pick a functional interface that has a method with an int parameter and a void return. The standard interface for processing int values is

public interface IntConsumer

{

void accept(int value);

}

Here is the improved version of the repeat method:

public static void repeat(int n, IntConsumer action)

{

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) action.accept(i);

}

And here is how you call it:

repeat(10, i -> System.out.println("Countdown: " + (9 - i)));

Table 6.3 lists the 34 available specializations for primitive types int, long, and double. As you will see in Chapter 8, it is more efficient to use these specializations than the generic interfaces. For that reason, I used an IntConsumer instead of a Consumer<Integer> in the example of the preceding section.

Table 6.3 Functional Interfaces for Primitive Types p, q is int, long, double; P, Q is Int, Long, Double

![]() TIP:

TIP:

It is a good idea to use an interface from Tables 6.2 or 6.3 whenever you can. For example, suppose you write a method to process files that match a certain criterion. There is a legacy interface java.io.FileFilter, but it is better to use the standard Predicate<File>. The only reason not to do so would be if you already have many useful methods producing FileFilter instances.

![]() NOTE:

NOTE:

Most of the standard functional interfaces have nonabstract methods for producing or combining functions. For example, Predicate.isEqual(a) is the same as a::equals, but it also works if a is null. There are default methods and, or, negate for combining predicates. For example, Predicate.isEqual(a). or(Predicate.isEqual(b)) is the same as x -> a.equals(x) || b.equals(x).

![]() NOTE:

NOTE:

If you design your own interface with a single abstract method, you can tag it with the @FunctionalInterface annotation. This has two advantages. The compiler gives an error message if you accidentally add another abstract method. And the javadoc page includes a statement that your interface is a functional interface.

It is not required to use the annotation. Any interface with a single abstract method is, by definition, a functional interface. But using the @FunctionalInterface annotation is a good idea.

![]() NOTE:

NOTE:

Some programmers love chains of method calls, such as

XXX String input = " 618970019642690137449562111 "; boolean isPrime = input.strip().transform(BigInteger::new).isProbablePrime(20);

The transform method of the String class (added in Java 12) applies a Function to the string and yields the result. You could have equally well written

boolean prime = new BigInteger(input.strip()).isProbablePrime(20);

But then your eyes jump inside-out and left-to-right to find out what happens first and what happens next: Calling strip, then constructing the BigInteger, and finally testing if it is a probable prime.

I am not sure that the eyes-jumping-inside-out-and-left-to-right is a huge problem. But if you prefer the orderly left-to-right sequence of chained method calls, then transform is your friend.

Sadly, it only works for strings. Why isn’t there a transform(java.util.function. Function) method in the Object class?

The Java API designers weren’t fast enough. They had one chance to do this right—in Java 8, when the java.util.function.Function interface was added to the API. Up to that point, nobody could have added a transform(java.util.function. Function) method to their own classes. But in Java 12, it was too late. Someone somewhere could have defined transform(java.util.function.Function) in their class, with a different meaning. Admittedly, it is unlikely that this ever happened, but there is no way to know.

That is how Java works. It takes its commitments seriously, and won’t renege on them for convenience.

6.2.8 More about Comparators

The Comparator interface has a number of convenient static methods for creating comparators. These methods are intended to be used with lambda expressions or method references.

The static comparing method takes a “key extractor” function that maps a type T to a comparable type (such as String). The function is applied to the objects to be compared, and the comparison is then made on the returned keys. For example, suppose you have an array of Person objects. Here is how you can sort them by name:

Arrays.sort(people, Comparator.comparing(Person::getName));

This is certainly much easier than implementing a Comparator by hand. Moreover, the code is clearer since it is obvious that we want to compare people by name.

You can chain comparators with the thenComparing method for breaking ties. For example,

Arrays.sort(people, Comparator.comparing(Person::getLastName) .thenComparing(Person::getFirstName));

If two people have the same last name, then the second comparator is used.

There are a few variations of these methods. You can specify a comparator to be used for the keys that the comparing and thenComparing methods extract. For example, here we sort people by the length of their names:

Arrays.sort(people, Comparator.comparing(Person::getName, (s, t) -> Integer.compare(s.length(), t.length())));

Moreover, both the comparing and thenComparing methods have variants that avoid boxing of int, long, or double values. An easier way of producing the preceding operation would be

Arrays.sort(people, Comparator.comparingInt(p -> p.getName().length()));

If your key function can return null, you will like the nullsFirst and nullsLast adapters. These static methods take an existing comparator and modify it so that it doesn’t throw an exception when encountering null values but ranks them as smaller or larger than regular values. For example, suppose getMiddleName returns a null when a person has no middle name. Then you can use Comparator.comparing(Person::getMiddleName, Comparator.nullsFirst(. . .)).