RULE # 1

Always Demonstrate Your Value

WHEN BOB LEARNED that his name was on a list of IT employees whose jobs were to be downsized—a polite term for “fired”—he knew exactly what would happen next. This was the third time in five years he had gone through the same routine. He would attend a group meeting, which would be followed by a one-on-one session with an outplacement counselor, followed by an appointment the very next day to start his job search.

Bob would again be told that terminated employees should not dwell on negative emotions. Those who start on their job searches right away find work more quickly than those who do not. The group meetings always seemed to be held during the week but never on Fridays. He would eventually understand that outplacement firms got paid based on their “pick-up” rate—the number of people who actually start programs. Getting them to start without an intervening weekend improved the rate.

But Bob had more to think about than how outplacement firms made money. He was worried about his own finances and how long it would be before the family had to make major adjustments in their standard of living. He had new bills to consider, like health-care premiums and perhaps tuition for a return to school for the training required to change careers—to an area less subject to downsizing.

He also started to think about the damage this last layoff did to his reputation. Though aware that layoffs in some fields and industries are more common than in others, he wondered if employers were beginning to think that the problem was with him and that he simply couldn’t hold a job. Three jobs in five years would surely get a thumbs-down from hiring managers. They will want to know what’s wrong with me, he thought.

But now was not the time for self-analysis. First, he had to find a job, and he knew exactly what to do. He quickly updated his résumé by adding his most recent position to an already polished document. He had been taught by outplacement counselors: “Always keep your résumé up-to-date and stay in touch with your networking contacts.” Of course, most people hate to network. They are not very good at it and quit doing it the minute they find other employment. The motto of outplacement professionals Bob worked with was, “Be prepared and stay connected. And don’t forget to join as many self-help groups as you reasonably can. They will help you tap into the hidden job market.”

Bob would do all that, but this time he would make a significant change. He had learned about a new way to look for white-collar work: value creation. He noticed that certain people had figured out that their job instability wasn’t their fault. There was nothing wrong with them and they knew it. The skills each one brought to the job market were similar to those of others, yet these people appeared to be most in demand from employers. When he met them, he wondered, “What do they know that I don’t?”

During previous job searches, Bob approached the task in a predetermined sequential order: update the résumé; look for positions that match; and in knee-jerk reaction, apply for the jobs at hand. He now understood, however, that the requirements of similar jobs change from one organization to the next, depending on the specific problems each company is looking to solve. Now, his first order of business was to discover what those problems are and to adjust his application accordingly. Using this new approach, he landed an IT manager’s job at a comparable salary within five months.

Bob was convinced that his application got attention because of what he noticed about the position description. Besides the normal competencies every candidate is expected to have, there were key words in the job description that he could use to customize his résumé, making it specific for this job opening. The keys included the maintenance of a professional image (one of the main reasons the job was vacant), alignment of IT goals with corporate strategy, and IT policy development. These were skills Bob had demonstrated in previous positions. This time, however, he made sure they were emphasized throughout the application process—including in his résumé, cover letter, and interviews. The key points represented areas in which the hiring organization wanted value created. The IT manager positions in other companies might emphasize different problems. For each opening, it was important that he customize his résumé to address the areas the companies considered important and never assume that the same job in one company would address the problems in another company.

You should note that none of this made Bob’s job more secure. He could get a job one month and be downsized the next. He would, of course, be disappointed but not downhearted. There was nothing wrong with him, and he knew it. He also had the added advantage of understanding value creation and the role it plays in today’s marketplace of jobs. He is now able to adjust his approach to finding a job to reflect the new realities in the market—adjustments he would not have made using the same job-search methods he had learned earlier. At one time, employers were impressed by his familiarity with different aspects of information technology. He now understood that they wanted more. He had to emphasize how his skills matched the job descriptions of potential employers. He received a lot more interest once he focused on exactly what employers wanted, and as a result, he became a lot less anxious about instability in the white-collar job market.

The Demand for Value Creation

Those who understand how the job search has changed over the years have turned their career ship around so it’s headed in the direction of creating value for others. That’s the innovation my firm has pioneered, after I’d worked in human resources, global outsourcing, and the outplacement industry for twenty-five years and had read untold thousands of résumés. When we began the process, we understood the job market in general but not how our particular method would work out practically.

We tested the process first on family and friends and then on a broader audience. The results were strikingly similar. We put together a value-creation workshop for soon-to-be college graduates from the Knowledge Is Power Program (KIPP) in New York City, and we offered a slightly different one for students from Michigan State University’s prestigious James Madison College. In all instances, the students dramatically improved their ability to navigate their job searches as a result of our programs. One student commented that the workshop was a humbling experience that has motivated her to revisit her entire job-search strategy.

Dan, the volunteer research assistant for my first book, Are There Any Good Jobs Left? is a good example. Dan was a typical soon-to-be graduating political science major at Northwestern University. He knew he wanted a job in private industry but was not sure how to go about getting one or how to make the best impression on employers. Furthermore, political science was not a typical major for someone interested in a business career. Using our value-creation method to develop a résumé (and write cover letters, prepare for interviews, and eventually manage the full range of his career), Dan applied to fourteen companies, got eleven interviews, and had three job offers—all at more than twice the going salary for social science majors. We then tested the method on more experienced job seekers. The results were the same—value creation is a language employers understand and job seekers can use to effectively make themselves stand out from the competition.

Using the value-creation method initially feels like little more than a résumé-writing process. That’s certainly the way it felt to Jenny. When we met her, she had already paid a consulting service $600 to develop a résumé. She got a professional-looking document—but one that was of little use to her in a job search because it was no more than a summary of what she thought was important about her background. It lacked mention of what particular companies considered important as they advertised their positions.

An unfocused résumé is a little like fishing without bait—if you catch something, it is strictly by accident. And Jenny wasn’t catching anything. Though she had previously worked as a personal consultant on an hourly basis, that fact wasn’t part of her current résumé. As a result, her expensive document was useless for the freelance marketing/public relations job she was now interested in pursuing. The job she eventually applied for and got was as a public relations consultant for a Washington, D.C.–based lawyer who wanted to increase his visibility in the legal community. That happened because once Jenny understood the value the lawyer was looking to have created, she adjusted her résumé to reflect her accomplishments in those areas. For instance, she emphasized her experience in developing short- and long-term marketing/PR strategies; her effectiveness in pitching to local media outlets; and her broad knowledge in developing a media list—all things she had done but had not, until now, highlighted. Once Jenny applied the concepts of value creation, her job-hunting fortunes turned around. So can yours.

Why the Job Market Changed

It is taking longer to find suitable work these days, and people are growing uneasy about whether there are enough jobs to go around. When you feel that things are rapidly spinning out of control, there is a tendency to look inward and lose confidence. Yet most of the time the problem isn’t you. Today’s job market has been mightily affected by globalization, changes in technology, and the deregulation of various commercial sectors in the United States and elsewhere. Briefly, here is how each affects your job search.

GLOBALIZATION

The world is poised for more, not less, globalization so we might just as well get used to it. Corporations that operate as global players have a tremendous advantage over those that do not. As a result, products are increasingly made overseas, where labor is cheaper. That doesn’t only include factory work or telemarketing; even professional work is often outsourced. For instance, Craig was a software engineer who had been laid off for the second time in a year and a half. The work his department did was outsourced—once to another department in the same company and another time to a company in India. Some professionals in the automobile industry had similar experiences when Chrysler merged with Mercedes. It did not take long for many of the automobile design jobs to be relocated to Germany. Craig’s initial thought was to return to school and pursue a course of study and a career less susceptible to outsourcing.

His strategy was flawed, for a simple reason: the future is uncertain. How is he supposed to determine how globalization might evolve over the next few years? What if his new line of work later proved to be susceptible to the same outsourcing pressures as his previous employment? At one time, most of us thought heart surgery, income-tax preparation, and drive-thru order taking at McDonald’s were all safe from outsourcing. That is no longer the case.

None of us can predict with certainty what impact globalization will have on certain job classifications five years down the road. In a global world, jobs are fluid. For example, a CEO relocated to St. Louis for one month, and because of a merger, his job was eliminated sixty days later. In many other cases, new employment opportunities ended much sooner than anyone anticipated. Because these upheavals are difficult to predict, it is better to be prepared for job instability than to try to avoid it altogether. White-collar professionals need to develop the skills required to survive and prosper in today’s job market, regardless of how unstable one particular job turns out to be.

That idea of adaptability includes retraining yourself in response to an unstable work environment. Retraining is always an option—just not the first one to consider, because it is a time-consuming, uncertain path.

TECHNOLOGY

The Internet may emerge as the single most important technological innovation of our time. But it also has increased the instability in the workplace. Among other things, the Internet:

![]() Spread near-instant communications across the globe and for a relatively low cost, making possible the 24/7, 365-day world we live and work in

Spread near-instant communications across the globe and for a relatively low cost, making possible the 24/7, 365-day world we live and work in

![]() Allowed the cost of data and product distribution to be reduced

Allowed the cost of data and product distribution to be reduced

![]() Made price data for an endless variety of goods and services available, driving prices and profit margins down

Made price data for an endless variety of goods and services available, driving prices and profit margins down

![]() Reduced the barriers to entry for niche businesses and enhanced their ability to grow larger without additional cost—an important consideration for a new class of entrepreneurs

Reduced the barriers to entry for niche businesses and enhanced their ability to grow larger without additional cost—an important consideration for a new class of entrepreneurs

![]() Generally intensified the global competition for goods and services

Generally intensified the global competition for goods and services

What has any of this got to do with the job market in which you compete? Everything! It is like learning to make lemonade when you are stuck with lemons, as the cliché goes. That is what Heather did when the responsibilities of the compensation department in which she worked were outsourced. It was no longer necessary for her company to maintain an entire staff of compensation specialists. Near-instant communications allowed it to buy those services on a just-in-time, as-needed basis. Heather’s recourse was to use her expertise and technology to establish a 24/7 international compensation-consulting firm. With a remarkably few number of employees (ten people headquartered in Marin County, California; two in New York City; one in London; and two in Singapore) hired as temps on an as-needed basis, she was able to transfer work electronically (at essentially no extra cost) from one time zone to another, to be worked on until completed.

Heather’s firm was set up to service other newly emerging global businesses that suddenly found themselves in need of a uniform compensation system for their employees around the globe, which would help them remain in compliance with different national pay systems, meet the legal requirements, and abide by local customs—all the while maintaining some semblance of internal global equity. Her typical call came from a new client in the midst of a merger or acquisition that could not be completed until the deal included specific language about compliance on compensation issues. Heather soon built a loyal following of corporate clients that trusted her judgment and relied on her quick turnaround times.

Globalization and technology have combined to create instability in the workplace. Heather used those elements (and the value she had learned to create) to create her own business opportunity. In other words, technology is a source of instability as well as a great enabler. You, too, can reasonably pursue business ownership as an employment alternative. When companies outsource, they often outsource to the same workers they laid off. And it is possible to perform those functions across several organizations in ways that bring greater take-home pay and provide more personal time than ever imagined. Many people have taken this route once they got over the trauma of being fired. There are added risks, to be sure, such as having to purchase your own health-care coverage, coping with an uneven income stream, and having to continually search for new business.

DEREGULATION

The final death blow to the stability of our work environment was dealt by deregulation. Once upon a time, regulations protected established companies from “excessive” competition. But once the restrictions were lifted, industries such as financial services, communications, and transportation lost their “protection.” Suddenly, banks were allowed to do business across state lines and could place ATMs on every corner. Brokerage houses could own banks and vice versa. Airline ownership did not disqualify ownership of trucking companies, steamship lines, or railroads, as had previously been the case. And on it went. New kinds of competition fueled the business drive for increased productivity and efficiency.

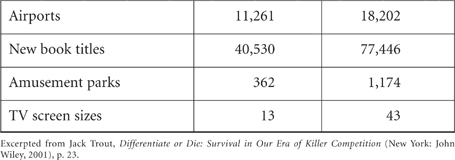

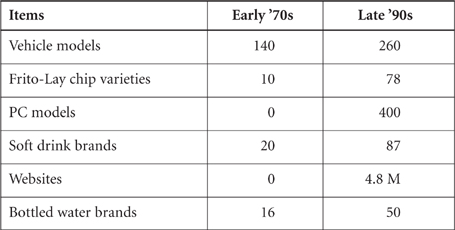

These developments, along with other changes in technology, began to give customers choices they never had before—cheaper airline seats, more automobiles, newly created financial instruments, more soft drinks, alternative types of telephones, computers in new forms, and so on. Many theorists have called the decades of the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s the “explosion of choice” era. The following table gives you an indication of how large these changes have been.

THE EXPLOSION OF CHOICE

The movement of jobs around the world, especially to India, China, and Russia, has helped those economies mature and increase worldwide competition for goods and services. If company A does not offer the size TV screen people want at the price they want it, they will simply buy from company B that will, regardless of where the TV is made. “Buy American” only works as a slogan if the product is at the best price and has all the bells and whistles that consumers want.

The increased choices for customers spawned high-growth companies like Walmart, which could effectively squeeze suppliers and offer lower prices. Meanwhile, employees got slimmer benefit packages, pensions that often ended as idle promises, and eventually pink slips—all to increase profit margins and gain competitive advantage. The old days when giant companies at the top of the business pyramid knew their production requirements years in advance, and could hire off the college campus and slot employees into positions over time, are long gone. Now, companies face an unprecedented sense of urgency in which, for example, the typical consumer-products company loses half of its customer base every four years, according to economist Robert Reich, who noted this development in his book Supercapitalism: The Transformation of Business, Democracy, and Everyday Life.

When you look for that next job, you should understand that loyal, long-term customers and employees are dying breeds. Instead of cradle-to-grave employees, corporations hunger for people who can create value and who are around only for as long as they are needed. The employer-employee relationship has taken on an entirely new meaning. The tradition was that of having loyalty to the company in exchange for a secure job with generous benefits. That’s over. According to Peter Capelli, author of The New Deal at Work: Managing the Market-Driven Workforce, the new mantra is, “If you want loyalty, get a dog.”

Turn the Key of Value Creation

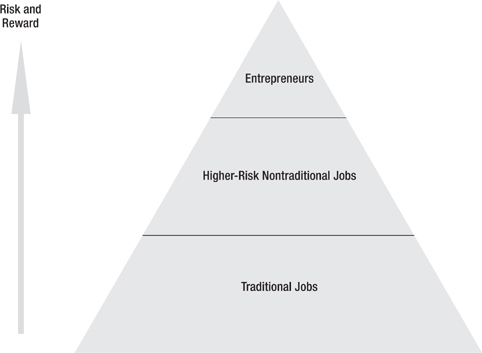

The ability to create value for a company repositions the traditional white-collar worker for today’s job market. But what exactly is entailed in value creation? There are three interconnected value sectors in today’s market: value creation for an employer; value creation as a member of the contingent workforce; and value creation as an entrepreneur. Figure 1.1 presents these sectors as a pyramid, with increasing levels of risk as one rises from traditional employment at the bottom to entrepreneurship at the top. The value inherent in these levels is interconnected because mastery of one helps you gain mastery of the others. That is, all of us need to get better at creating value for ourselves and our employers—learning to effectively operate in one arena opens the door to the others.

FIGURE 1.1 Value-creation pyramid.

Since my first book on the subject, Are There Any Good Jobs Left? was published, people keep asking for a repeat answer to the book’s central question: Are there any good jobs left? The answer is a resounding “Yes!” The salaried jobs with attached health-care benefits and pension programs we have grown accustomed to will continue to exist—but with a major caveat. Proportionately, there are fewer of those jobs today than there were yesterday, but there are more today than there will be tomorrow. One way to survive is to become more competitive for the good jobs that remain. And this can be done by learning the language of value creation.

Unemployed white-collar professionals often wonder if more education will make their job situation more stable. They know a college degree today is merely the equivalent of a high school diploma of a generation ago. More education, the hope is, will make you more competitive for the jobs that remain. Colleges and universities endorse this idea because they, like other businesses, are in a mad scramble for more students and the revenue stream they represent. The truth is, there are no guarantees.

If you doubt that, visit your local Starbucks. Workers there are a pretty educated bunch. If you are able, approach one and ask, “Is this the kind of job you had in mind when you went to college?” For instance, Marilyn majored in music education and had been working at Starbucks for two years following graduation. While in college, little did she realize that music programs in American schools had for years been pared back and in many no longer existed. Colleges and universities, however, were not deterred by the lack of career opportunity and kept advertising music education as a viable career option. Faced with the prospect of postgraduate unemployment, she wasn’t going to make the same mistake twice and passed on the opportunity to study for a master’s degree in the same field. Instead, she moved back in with Mom and Dad (65 percent of college graduates do that immediately following graduation) and took a job to pay off her student loans. What about the career? She simply says, “It’s on hold.”

Even the gainfully employed know that someday they, too, will be forced to test the job market. That’s because the typical white-collar worker can expect to have at least ten jobs and three to seven careers during his or her lifetime. The question for all of them is, “How do your credentials match up with those of the people whom you must compete against?”

In the 1980s, outplacement firms reassured displaced white-collar workers that the reemployment statistics were on their side. Some firms even argued that white-collar layoffs were really “blessings in disguise.” Former employees could take advantage of the interlude to search for positions and careers for which they were better suited, as compared with earlier ones that they most likely stumbled into. This was a time during which they could discover their true calling and could work at jobs they were more passionate about.

During a previous time, unemployed white-collar workers could expect to find new work quickly, at comparable income levels or better. The old rule was that a job search would take one month for every $10,000 of income. To find a job at the $60,000 level would take around six months. Many white-collar workers boasted that their new jobs actually paid more than their old ones.

Things have changed so dramatically that the unemployed are in need of new rules for finding white-collar work. Relying on your work history and formal credentials alone is problematic; thousands of other people with good credentials also cannot find work on a par with their expectations. The situation cries out for a better approach.

Adding to the problem, of course, is the increased number of people you are competing against. Job listings for white-collar workers attract hundreds (would you believe thousands?) of applicants. Government jobs that once went begging are now drawing 150 percent more applications than in previous years. A few years ago, Walmart boasted it had 25,000 applications for positions at just one of its new stores. A college graduate who was interviewed on National Public Radio ended up landing one of the station’s entry-level positions and acted as if he had hit the lottery. Overcrowded job fairs around the country—in Memphis, Raleigh, Detroit, Minneapolis, and San Francisco—are but a few examples of the numbers of white-collar workers flooding the marketplace. If you are among the millions looking for work today, you must stand out from the crowd and stay ahead of the competition.

How do you do that? Some people join self-help groups. After all, a pool of people can find more new openings than one person alone can. Yet, there are shortcomings to this strategy. In most groups, the members do not share job leads until they themselves have been eliminated from competition; as a result, many of the leads are stale and of little use. The one thing the groups could help with—a sharpened focus on how to compete in a crowded job market—they seldom discuss.

Rather than share job leads, one group prepared a mock application for an HR position at IBM and then critiqued each other’s candidacy. None of the members had worked at IBM, nor was IBM on any of their radar screens as a possible job source—yet it was considered a highly desirable employer. The “educated guess” most of them made about IBM was that they hired outsiders only when filling entry-level positions.

As it turns out, most of what they thought about IBM was inaccurate. Of the 129 open HR positions (who knew there were that many anywhere, let alone at one company?), only four were in the United States. Several openings were in India, Europe, Asia, and South America—good news for some candidates who were fluent in other languages and open to moving internationally but bad luck for all the others.

Nevertheless, each group member was asked to compare his or her own credentials and cover letters with those of others in the group. All the cover letters and résumés were distributed and the participants were to independently award points for the best submissions. The exercise was designed to focus these job seekers on what they would have to do to be considered serious contenders for the job. Until then, they had been merely adding descriptions of recent jobs to their already polished résumés. The scores were tabulated and shared at the next meeting. Two candidates stood out as most likely to be invited for the first round of interviews—even though they did not have the most experience or attend the most prestigious schools.

The group discussed why these two résumés, in particular, stood out. The answer was that the two submissions demonstrated the closest links between what IBM said it was looking for and what was emphasized on the applications, including the résumés. The exercise encouraged the group members to examine more closely the requirements of each job for which they apply. After the experiment, their résumés became more focused instruments. Shortly thereafter, each member experienced a spike in interviews. Their competitive edge had little to do with the school attended, whom someone knew, or what social group they belonged to. The most important variable was their ability to demonstrate value creation.

Here is an example of changes one person made in her résumé once she focused on value creation:

Current Résumé Section

Director, Executive Staffing, ABC Corporation

![]() Responsible for coordination and direction of executive staffing worldwide (50–60 hires per year).

Responsible for coordination and direction of executive staffing worldwide (50–60 hires per year).

![]() Successfully met cost/hire and time-to-fill metrics.

Successfully met cost/hire and time-to-fill metrics.

![]() Successfully managed professional staff of three recruiters and executive search firms.

Successfully managed professional staff of three recruiters and executive search firms.

Position Description

Company seeks experienced executive staffing professional who will:

![]() Reestablish staffing function credibility as a legitimate business partner.

Reestablish staffing function credibility as a legitimate business partner.

![]() Facilitate management decision making in a politically sensitive environment.

Facilitate management decision making in a politically sensitive environment.

![]() Meet or exceed strict requirements of cost/hire and time-to-fill standards.

Meet or exceed strict requirements of cost/hire and time-to-fill standards.

Revised Résumé Section

Director, Executive Staffing, ABC Corporation

![]() Established function’s credibility with senior management and other key stakeholders as evidenced by consistent performance rating of outstanding. Shortened new executive learning curve by designing and implementing a year-long orientation/on-boarding program.

Established function’s credibility with senior management and other key stakeholders as evidenced by consistent performance rating of outstanding. Shortened new executive learning curve by designing and implementing a year-long orientation/on-boarding program.

![]() Consistently exceeded strict standards of cost/hire (15%) and time to fill (10%). Implemented annual client satisfaction survey as key component of staffing function’s continuous improvement effort.

Consistently exceeded strict standards of cost/hire (15%) and time to fill (10%). Implemented annual client satisfaction survey as key component of staffing function’s continuous improvement effort.

![]() Became respected business partner as evidenced by being asked to join management roundtable (a politically sensitive assignment) to assess new executive contribution as a component of company’s annual management review.

Became respected business partner as evidenced by being asked to join management roundtable (a politically sensitive assignment) to assess new executive contribution as a component of company’s annual management review.

The revised résumé section is clearly more focused on the specific requirements of the position, and it promises to create the kind of value the hiring organization is seeking. Another way of looking at value creation is to remember that your résumé is not just a summary of what you have accomplished. It is a promise of what you can accomplish for someone else.

A department head once asked whether it was more important to “look good” or “be good.” His answer came as a surprise to the staff. He said, “Look good.” His rationale was that if you are, in fact, no good, you will be found out soon enough. But if you do not at least look the part, no one will ever have enough confidence to give you a chance to perform. In this case, “looking the part” means constructing a résumé that speaks specifically to the value a hiring organization is looking to be created.

As it turns out, there is ample opportunity to create value in a variety of settings, including as a traditional or nontraditional employee or as an entrepreneur.

Create Value as a Traditional Employee

In a job market in which more people with college degrees are competing for fewer good jobs, the advantage goes to those who most closely approximate the skills and contributions employers are looking to acquire. Hiring managers prefer people who can make a difference to their bottom line. Your ability to demonstrate that potential by drawing parallels between your previous experiences and an employer’s needs is crucial in getting hired and remaining employed.

The ability to demonstrate value creation, thus, is a fundamental requirement of the new job market. It is as simple as putting yourself in the shoes of the employer. In our workshops, we do this by asking the question: Whom do you hire? We answer it by listing two sets of credentials side by side and comparing them to the job specifications from the employer. Workshop participants get it every time. The school you attended and your college major are much less important than your ability to extrapolate what an employer requires from the experiences and training you currently have.

We cover the steps required to write an effective résumé in our workshop. Here, we begin to reveal how to succeed in today’s job market. Most job seekers understand that a résumé is a onetime opportunity to establish a link to a potential employer. How do they create a document that puts their best foot forward? The light begins to go on when they understand that their résumé is not really about them. In fact, the best résumés—and the ones against which you must compete—are arrows shot directly at their target. They take into account the needs of hiring organizations and then link those needs to the candidate’s own accomplishments.

CARESS THE DETAILS

Typical résumés are, more often than not, simply summaries of someone’s work history. But those that garner attention do considerably more. That is what Sheila found when she lost her first job, five years out of college. At the time she was working in marketing as a supervisor for a large consumer-products company. She had a run-in with her boss, was fired, and by mutual agreement, they treated it as part of a more general layoff. This happens a lot.

At first, Sheila wasn’t too concerned about finding another position because of her solid work experience and her degree from a prestigious university. So, the difficulties she had finding her next job came as a surprise. Sheila discovered that lots of well-educated, out-of-work professionals had her level of experience—and more. It was a mistake to assume that her credentials would “speak for themselves.” Eventually, Sheila focused on how her job experiences and education uniquely positioned her to make contributions that were important to the companies to which she applied.

Presenting your credentials to the job market as if your previous work history and college degree are enough to carry the day is a critical mistake. Of necessity, employers are interested, first and foremost, in themselves and their profitability. This applies to not-for-profit sector jobs as well! All organizations want to know what’s in it for them if they hire you. Can you create more value than your competition? Remember, many other candidates have the same or similar credentials—you have to demonstrate that your credentials really fit better. You have to make it easy for hiring managers to see how your background will answer their needs. Always translate your background into what a company needs.

Never assume that the connection between your experience and the company’s needs is obvious—or that the hiring organization will connect the dots. For example, if a company is looking for a financial analyst, it is not enough for it to know that you have been a financial analyst. One client in particular mistakenly thought his résumé should be a summary of “major” areas of responsibility. Meanwhile, the position description specifically called for someone with experience in ad-hoc reporting. Though he had, from time to time, done that kind of work, it was not a major area of his responsibility and so it never made it into his résumé—at least not until it was pointed out that he needed to be more responsive to the needs of the hiring organization, that he needed to create value. The lesson is: Always find out the details of what is required and make sure your résumé includes them. The value the hiring organization is looking to have created is often found in those details.

REALIZE THAT IT’S NOT ABOUT YOU

Initially, our workshop participants are confused when we tell them their résumés are not about them. They wonder if we are suggesting that they lie or exaggerate their accomplishments. The answer is a decided “No!” The résumé describes the truth about what you have to offer, but that truth framed in terms of the hiring organization’s needs, not your needs.

Understand that the context for the presentation of your credentials is provided or shaped by the requirements of the position—not vice versa. For example, the way you might position your project-management experience should be driven by the specifics of a company’s interest in project management. Even worse, if project management is not a requirement for the position, that credential should not occupy a prominent position as you present your credentials for consideration.

Once their confusion ends about the tail wagging the dog, our clients are better able to present their skills against the backdrop of the job market. It is surprising that so many people put their résumés together without the slightest consideration of what the job market or a particular organization requires. They wonder why they never hear from companies with job openings. For instance, Tom had a Ph.D. in English literature, and he included that as part of the educational summary on his résumé, even though he was looking for an entry-level position in pharmaceutical sales, where he had been working for the past two years.

Tom had applied for a number of advertised positions but was either ignored or advised that he was “overqualified.” Companies say that from time to time so as to dismiss candidates in whom they have no interest. They may also be concerned that overqualified applicants will move on to other employment the minute they have a chance. The problem, we decided, was that Tom’s résumé was unfocused. It did not provide hiring managers with a compelling reason to consider his candidacy. In a more focused version, the Ph.D. mention was dropped and Tom got two invitations to come in for interviews.

ANTICIPATE THE FUTURE

Once people understand how to create real value for themselves and for their potential employer, two things begin to happen. First, they become more valuable in their current position and less subject to downsizing and outsourcing. At the very least, an organization must do the calculation to determine if it really makes sense to let you go. However, no one should be led astray. Few of us are ever in a position to create enough value to overcome the perceived advantages of mergers and acquisitions, let alone advances in technology. The word perceived is used here because the overwhelming number of mergers and acquisitions never return anywhere near their premerger advertised value. That doesn’t help you, though.

The second advantage of value creation is not the protection one gets against termination. (Remember, it is still an unstable job market and will remain so for the foreseeable future.) It’s that by stressing value creation, you start to realize that you can create a value that is marketable and can be sold to others. That value can be sold either to a single organization through your job search or to multiple organizations that are willing to pay handsomely to get it. Value creation allows you to regain control of your career. Plus, it builds your confidence!

The route you take to sell the value you create will depend on your comfort level and flexibility. The more traditional approach is one of selling your value to a single employer in exchange for security of income and other benefits. But that security is on the wane. At some point, you will have to convince another employer of the value you can create for it as well. In this instance, being fired may not feel any better, but at least you can understand that the problem is not so much with you as it is with an unstable job market.

CARRY OVER THE CONCEPT TO YOUR CHILDREN

If you have children, you know that considerations of the future should include them. You may want to know how to help them with their careers, for example. The job market is so unstable and competitive today that parents are resorting to desperate acts. For example, Christy’s parents moved beyond footing the bill for her undergraduate degree and paid $10,000 to have her placed in an unpaid nine-week internship that, in their estimation, would provide her with a competitive edge in the entry-level job market. Though it was a questionable action, they correctly understood that hiring decisions are based on perceptions of the value applicants can create for the companies for which they want to work. An internship (even when paid for by Mom and Dad) can provide that competitive advantage.

The emergence of these kinds of internships as a significant source of access clearly advantages families that are relatively well off, at the expense of others not quite so fortunate. Rather than pay for an unpaid internship, start teaching your children about value creation very early in the game—perhaps as early as middle school. This was the advice my consulting firm gave to the Knowledge Is Power Program (KIPP) as they worked with building the career skills of middle-school kids from underserved communities. Once students leave middle school, they stay tethered to KIPP through a series of employment opportunities and academic support programs all the way through college.

For every job the students took, KIPP would require a one- or two-page essay on what the organization did and what value it created for its clients. The final paragraph or two should focus on their jobs and how they contributed to that value the organization created. The exercises were designed to give students a jump on understanding the link between value creation and hiring. By the time those KIPP students are in college, they will be far ahead of others with regard to understanding what companies look for in entry-level hires.

We know that the number-one concern parents have about their college-age children is whether they will choose a course of study that leads to a stable, well-paying career. Yet, campus recruiters continue to say that the college major is not their number-one priority in hiring. Organizations are more interested in leadership qualities and communications and analytical skills. One of the surest ways students can make the leap from college to employment is by understanding the language of value creation and being able to communicate that value potential to hiring companies. It is not so much what the students choose to major in as it is what they learn to do with the knowledge they gain. (See also Appendix A.)

Create Value as a Nontraditional Employee

The contingent workforce is made up of people who have nontraditional work arrangements. Mostly, they are temporary employees and independent contractors who work on an as-needed basis. At one time, outplacement firms advised clients to avoid temporary work because those arrangements got in the way of the search for permanent full-time employment. This advice was given as though contingent work was undesirable. And for some, it is. But the size and complexity of this workforce has grown to approximately 14.8 million workers and is now 11 percent of the U.S. workforce. And according to the Occupational Outlook Handbook’s projections, it is expected to grow an additional 45 percent. Whether individually desirable or not, nontraditional work arrangements constitute too large an opportunity to dismiss out of hand.

Once people understand their ability to create value, it is a short conceptual leap to considering selling that value to more than one organization at a time. Owning the ability to create value offers you the strength and security of multiple sources of employment. If jobs are here today and gone tomorrow, having multiple sources of income starts to look like a more reliable and less risky path to follow. And it is easy to see how multiple buyers and greater demand than you can reasonably supply can ultimately mean greater income than you would have from a single employer.

For most of us, however, developing multiple sources of income seems an unrealistic idea. That is because we have grown up working for one company at a time, possibly for a long time. Making the leap to the world of contingent work takes courage and imagination. You need to have a skill set that someone wants and the flexibility to deliver your services in a nontraditional setting. The risks involved, both perceived and real, can be daunting.

Are you ready for this new order of jobs? Flexibility is the first quality you need in this field of nontraditional value creation. Perhaps the best indicator of whether you are a candidate is to measure your flexibility. Ask yourself, “Would I prefer to have my current income be salary based and paid at regular intervals, or 100 percent variable and driven by whatever revenue contribution I make to the business, day to day?” If you prefer compensation based on your contribution, you are more willing than most to depart from traditional work arrangements. That’s an indicator of your flexibility, a good quality to have in today’s job market.

Additionally, nontraditional work is not limited to offering services on an as-needed basis. Even in a single-employer situation, you can use value creation to build a new type of relationship. For instance, Julie grew tired of working for physicians who did not respect her skills as a nurse practitioner. (This, by the way, is by far the most common complaint of nursing professionals.) She had a loyal following of 600 patients, many of whom had demonstrated a willingness to follow her from one practice to another in her never-ending search for a better employer. She finally sent a letter to a new physician group with an offer they couldn’t refuse. They found it attractive enough to ask for more information.

“I propose,” Julie said, “that I work with you to build a successful practice. I have been in the area for fifteen years and have a loyal cadre of patients who will follow me to this practice.” By the end of her interview, the doctors could no longer contain their enthusiasm. They offered her a position at an attractive salary on the spot. Rather than turn it down, she made a counteroffer of a bonus for each new patient she recruited to the practice. In other words, she wanted to work with, not for the doctors and reap more of the benefits of the value she was creating. Thus, her compensation was based on a nontraditional work arrangement. Julie understood value creation and was willing to assume the risk that came with offering that value in a nontraditional way.

TEMPORARY WORK

Temporary spikes in the demand for people are often met by temporary workers (quasi-employees), sometimes hired through temp agencies. These temporary employees can easily be let go once demand subsides, so organizations prefer them when future demand is uncertain. At one time, temps were largely clerical employees. Now they include lawyers, accountants, physicians, hospital administrators, salespersons, executives, and miscellaneous other professionals. Those who are the best at what they do—that is, who create obvious value for the organizations with which they work “temporarily”—are sometimes asked to join on a permanent, full-time basis. In this sense, the temporary work is a trial run, during which both organization and employee get to know one another. Today’s temporary workers can also command substantial compensation by selling their skills to the highest bidder or to multiple bidders. In short, the old advice to avoid temporary employment is not as reliable as it once was.

Temporary positions can have benefits that serve both parties. Robert, a physician friend, leaped at the chance to become the “temporary” CEO of a medium-size hospital chain. The opportunity was attractive to Robert because it allowed him to commute rather than relocate. It was attractive to the hospital because having a “temp” in the position gave the hospital board time to make a more deliberate decision. The arrangement lasted a little over two years—the length of time it took to groom an internal candidate who was not fully ready when the opening first occurred.

The temporary employee who tracks the contribution (value) he or she creates, and who broadcasts those experiences to others who also may need those services, is uniquely positioned to capture the dynamism of today’s job market. Risky? Perhaps—but no more so than relying on a traditional job in a company more interested in return on shareholder equity than on your personal well-being. As our society transitions from one workforce configuration to another, the opportunity to remain employed on a temporary basis grows as well.

AS-NEEDED CONTINGENCY WORK

Once Leigh understood value creation, she started her curriculum-design business. Companies with small training departments that want to offer an in-house curriculum often choose to hire outside consultants to design those programs. Leigh has been in the business for seven years, and as her clients move to other companies in the metropolitan area and beyond, they use her curriculum-design services as needed, on a contingent basis. All of her brand development and advertising is word of mouth, and she works hours that allow for an active social life and for raising three children.

People are often surprised to learn that Leigh does not have a graduate degree, because she runs a successful business in a field that usually requires one. “How do you respond,” she was once asked, “when a request for proposal (RFP) calls for a master’s degree?”

“I ignore it, list my references, and apply for the work anyway. And I get a lot of it.” Her reputation for solid work trumps the degree requirement every time. That would likely not be the case if companies were considering her for full-time work. She had initially developed her curriculum-design skills as a clerical employee who took advantage of internal-development programs and on-the-job training. Once her department was downsized, Leigh found a niche in the job market that would likely not be there in a more traditional setting.

Although value creation can be applied across a wide spectrum of situations, it is of particular use in the world of white-collar work, and it is crucial to any attempts to offer as-needed services. Experienced workers, tossed about by job instability, can summon their knowledge and skills to offer that value as services on an as-needed basis, thereby working more for themselves than for others.

Create Value for Yourself as an Entrepreneur

While the age of entrepreneurial innovation is upon us, it is not for the faint of heart. Starting your own business can be a high-risk/high-reward game, with implications that may not be fully understood at the start. No less prominent a figure than Warren Buffett counseled against this game’s excesses when he noted that all great opportunities include innovators, imitators, and idiots.1 Figuring out where you stand in the lineup is no easy task. Innovators make a contribution to society, but they do not necessarily make money because they often have to focus on running the operation that turns their ideas into practical products or services. Early imitators often make money because the ideas they have copied are new, still in demand, and operationally functional. In this sense, it is often better to be a trend-spotter than a trendsetter. The idiots, of course, are the “too little, too late” participants who try to cash in on an opportunity well past its peak.

The gourmet coffeehouse craze, prompted by the initial success of Starbucks and copied by numerous others, is a case in point. Rather than meeting an insatiable demand, new entrants now find the business tough sledding. This business sector may be a contracting market, with dramatically smaller profit margins than just a few years ago.

Innovation will also continue to appear, however, and it makes sense to be on the lookout for opportunities wherever you can find them. Who knew, for example, that ordinary people could safely lend money to strangers at a return below what banks and credit card companies charge, but well above what they can earn elsewhere? That idea started as a trickle on the eBay copycat www.prosper.com and quickly grew into a multibillion-dollar business with thousands of participants. Making a living from innovation requires both nontraditional thinking and a tolerance for risk.

Entrepreneurial innovation has been a particular boon for women, especially returning moms. What happened to Tina is a case in point. She met Dave while in college, they got married, and they decided to get his career up and running first and then she would soon follow suit. Three children and one divorce later, Tina was trying to kick-start her career. The difference now was that she really needed the money but didn’t have the support or experience to command the salary required to maintain her standard of living. The demands of a tight job market posed a unique set of problems for Tina and legions of other women like her.

Tina was eventually able to distinguish herself from the competition (that is, she was able to create value) because she learned how to cobble together experiences that emphasized her unique ability to multitask, organize, and attend to details. She first landed a job as a personal assistant for a busy executive who worked for a local nonprofit agency. This experience and the same skill set led her to develop a successful concierge service for busy women executives—especially those with young children.

Thus, a variety of people are finding their niches in the new job world as entrepreneurs. These groups include returning veterans, stay-at-home moms, newly graduating college students, laid-off white-collar workers, and many others. The current reduced barriers to entry and the ability to develop scale without cost have put even global business ownership within reach of many of us. The most risky of the three options for creating value, entrepreneurship can be the most personally rewarding.

![]()

![]()

![]()

By now you have a good understanding of what it takes to be successful in today’s job market: the concept value creation. That understanding now needs to be converted into specific action steps. That is, you need to focus on the mechanics of value creation, which begins with discussion of Rule #2. It is here where value creation really begins to come to life.

NOTE

1. “Charlie Rose Interviews Warren Buffett,” PBS, Wednesday, October 1, 2008.