CHAPTER 3

Business Results—the Company’s Health

BACK TO THE WAR ROOM

The fiscal year just ended, and the war room is rockin’.

Excitement is in the air, as the entire leadership team awaits its first glimpse of the company’s year-end numbers. Conversations swirl about the year’s big victories over the competition. People are thankful for the last-minute deals that closed just in time to be booked in Q4. Twelve long months of hard work have led to this single moment in time. All eyes are on the walls as the numbers begin to post.

So which numbers will be the stars of today’s party? The Number of Sales Calls that the sales force was able to make last year? That would be useful information if management were here to direct Sales Activities, but that is not today’s purpose. How about the Number of New Customers that were acquired during the year? That will be interesting to explore later, but even Sales Objectives are not important today.

The numbers that will make or break the mood in this war room are all Business Results. Did the company hit its Revenue target for the year? Did it eke out enough Profit to satisfy investors? These are the numbers that everyone has gathered here to see. Not measures of Sales Activities or Sales Objectives—just Revenue and Profit. Is this intense focus on Business Results short-sighted by senior management? No, it is not. In fact, this is how it should be.

Make no mistake—Business Results are the most important numbers on the wall. They are the corporate endgame. This is because Business Results are the primary measures of a company’s overall health. These metrics include such key performance indicators as Revenue, Profit, Market Share, and Customer Satisfaction—things that eventually find their way into financial statements and annual reports. These few measurements afford even casual observers a crystal-clear snapshot of an organization’s well-being. Good numbers reveal a healthy company. Bad numbers? Well, let’s not even think about that.

This is the primary function of Business Results—to gauge the general condition of a corporate entity. Far removed from any specific action of any individual, these measures are the culmination of the collective effort of an entire enterprise. Marketing, manufacturing, sales, and executive leadership, among others, all contribute to growth in revenue or increases in market share. When Business Results trend upward, everyone in the organization will take credit. When they trend downward, everyone will credibly point in the other direction. Unlike Sales Objectives or Sales Activities, any part of a company can lay claim to or disavow themselves of the outcomes that are Business Results. They are simply measures of overall corporate health.

DOING WELL

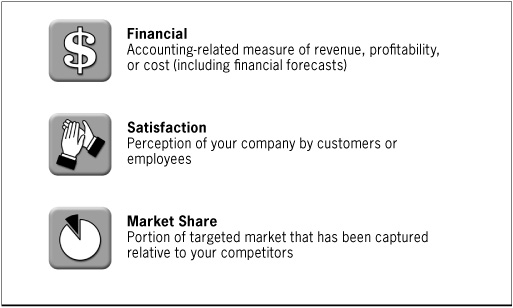

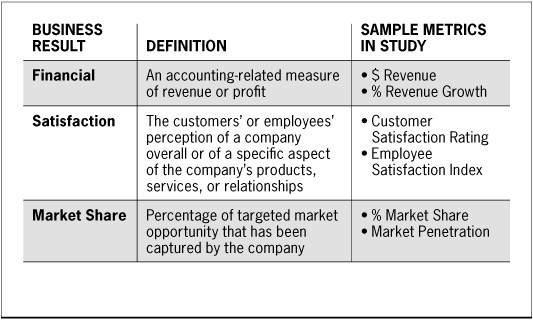

In our personal lives, this is the type of information we want when we ask about an old friend, “How is he doing these days?” What we hope to hear in response is, “He’s doing great! He likes his job, is in great health, has lots of friends, a good family. Overall, he’s doing well.” Business Results measure the corporate equivalent of “well.” If the company is growing, generates lots of cash, has a good position in the marketplace, and is loved by its customers, overall, it’s doing very well. See Figure 3.1 for the three main measures of Business Results.

FIGURE 3.1 The Business Results

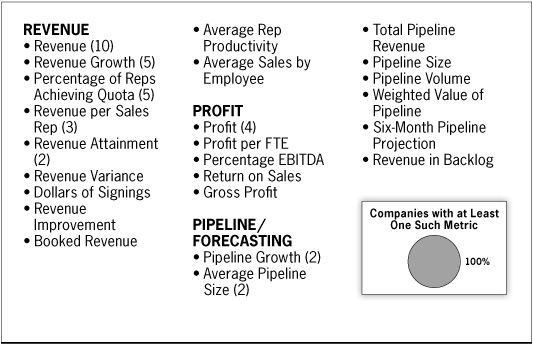

As you might imagine, we found several different ways to measure a company’s well-being. First, there are metrics used for self-examination that we called Financial. These are measures of health that the company defines for itself. How much Revenue does it want? How much Profitability would be considered a good Return on Investment? These Business Results are the objective financial parameters that leadership uses to judge its own progress toward its self-defined standards for “doing well.”

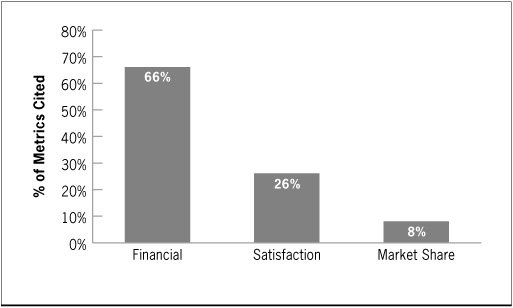

Second is a set of measurements that reflects the perceptions of others. They reveal how healthy the company appears to others whose opinions it values. We chose to label these measures Satisfaction, and they include the opinions of both an organization’s customers and its employees. Distinct from self-imposed Financial metrics, these numbers are highly subjective, and the criteria are largely defined by the customers’ and employees’ own personal experiences. See Figure 3.2.

FIGURE 3.2 Prevalence of Business Results by Category

Finally, we found a category of metrics that evaluates a company’s health relative to its peers. Measures of Market Share put success in the context of a competitive environment and assess which company has the healthier organization. In some industries, Market Share is the primary indicator of well-being, and a shrinking share of the market can spell certain death.

In sum, we identified categories of performance metrics that examine a company’s health from several perspectives:

![]() Do we think our company is healthy?

Do we think our company is healthy?

![]() Do others think it is healthy?

Do others think it is healthy?

![]() Is it healthy compared to its peers?

Is it healthy compared to its peers?

All good questions. Now let’s take a deeper look at what the answers might be for each.

It’s All About the Financials

![]() In the history of sales management, there is unquestionably an alpha metric—the very first measure by which a sales force was ever judged: Revenue. Even today, it is an obsession for almost every organization with which we work. Public companies are measured by it, CEOs’ egos are fueled by it, chief sales officers are fired because of it, field salespeople are motivated by it, and incentive compensation is driven by it. Ah, sweet Revenue, the all-powerful performance metric that needs no introduction.

In the history of sales management, there is unquestionably an alpha metric—the very first measure by which a sales force was ever judged: Revenue. Even today, it is an obsession for almost every organization with which we work. Public companies are measured by it, CEOs’ egos are fueled by it, chief sales officers are fired because of it, field salespeople are motivated by it, and incentive compensation is driven by it. Ah, sweet Revenue, the all-powerful performance metric that needs no introduction.

The other Financial metrics we encountered in our research also command considerable reverence. Long before there were the concepts of Customer Satisfaction, Market Share, or a Sales Pipeline, there were these fundamental accounting entries that eventually determine the life or death of every company. Go too long with low Revenue and no Profits, and the company doors are shuttered. As measures of corporate health go, these are the few vital signs that cannot be ignored. If these measures turn bad, nothing else can save you—it’s off to the crowded graveyard of failed businesses.

It is no surprise, then, that Financial metrics are the most predominant Business Results in our study. (See Figure 3.6.) They are the biggest and boldest numbers on War Room walls around the globe, and everyone in a company should have at least some interest in what they have to say. This is especially true of senior leadership, which is ultimately accountable for the story that the numbers tell.

As we wrote earlier, these numbers represent leadership’s own definition of a healthy company. Reporting $500 million in revenue and $100 million in profits doesn’t really tell a story unless the numbers are put into the context of a specific organization’s expectations. For GE or Wal-Mart, these numbers would communicate the equivalent of extinction. But for most small businesses, these numbers would tell a story of wild success. Unless the numbers spin a tale so tragic that it leads to bankruptcy, leadership itself is responsible for setting healthy expectations for its organization and the organization’s stakeholders.

Really, Financial metrics require little explanation. Managers have been collecting and reporting these numbers for centuries, so we will not force you to endure our redefining the obvious. However, there is one characteristic of Financial metrics that is worth exploring because it caused us considerable angst as we shuffled the metrics around on our war room wall.

Financial metrics, and Revenue numbers in particular, were frustratingly meddlesome as we stared at the wall trying to put the numbers into our crisp, clean categories of Results, Objectives, and Activities. This is because of the uncontrollable need by management to assign a Financial number to everything in its organization. Since these metrics are easily allocated using basic managerial accounting principles, almost everything in a company is likely to have a Revenue or Profit allocation assigned to it. What we found, then, were very confusing, multilayer measures that we came to call compound metrics.

When we saw a metric like Percentage Revenue Growth, we knew exactly what to do with it—into the Financial metrics bucket it went. However, when we encountered a measure like Revenue per Product Type, we were initially frozen in our tracks. Should that go into the Financial bucket since it’s a measure of Revenue, or should it count as a Sales Objective since it is tracking success in selling particular products?

Or if we came across Revenue per Sales Call, is that a Business Result since it is quantified in dollars, or should we categorize it as a Sales Activity metric since it refers to the activity of reps making sales calls?

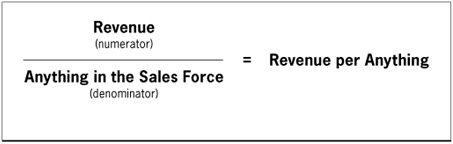

It quickly became apparent that Revenue can be assigned to almost anything you can imagine. We eventually concluded that these compound metrics were best thought of as basic fractions with a numerator and a denominator. For sales management, Revenue seemed to be the numerator of choice where Anything was the denominator. Over and over again, we encountered this frequently cited metric: Revenue per Anything.

Revenue per Rep, Revenue per Product Type, Revenue per Existing Account, Revenue per Stage of Sales Cycle—the New Question that had us baffled was this:

![]() What did “Revenue per Anything” really measure—the Revenue or the Anything?

What did “Revenue per Anything” really measure—the Revenue or the Anything? ![]()

This was a critical learning point for us as we tortured both ourselves and the numbers. After a good deal of ruminating, we concluded that the metric itself is not as important as what it is intended to measure (see Figure 3.3). With “simple” measures, such as Revenue Growth or Profitability, it was pretty clear that these metrics belong in the Business Results category. They were almost certainly intended to gauge the overall health of the company. The question this metric answers is whether the company is achieving its endgame goals that it set for itself.

FIGURE 3.3 A Favorite Metric of Sales Management

With the more complex compound metrics, we decided that they are most likely intended to measure the denominator of Anything rather than the numerator of Revenue. For instance, Revenue Growth from New Products is probably not intended as a yardstick for Revenue Growth—otherwise you could just measure Revenue Growth. It’s most likely used to gauge success in selling New Products, so it therefore belongs in the Sales Objective category. The objective is to sell more new products, and an easy way to measure progress toward that is to report whether revenue from new products is actually growing. Makes sense.

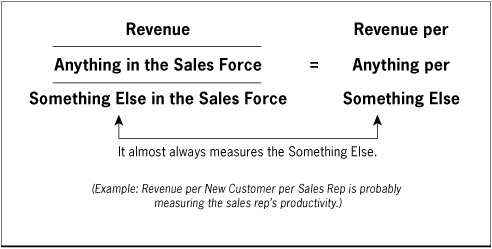

This phenomenon of designing elaborate metrics can be taken to extremes, and some of our more sophisticated clients like to push the boundaries. Take for instance a measure like Revenue from New Products by Stage of the Sales Cycle per Rep. Upon examination, this is not intended to measure Revenue, nor New Product sales, nor the Sales Cycle, though it might appear so at first glance (and second glance, and third). In reality, it is meant to measure the effectiveness of the Rep in selling new products, as measured by moving associated Revenue through the Sales Cycle (see Figure 3.4). Deciphering sales metrics can be quite an exhausting exercise.

FIGURE 3.4 What Does a “Compound” Metric Actually Measure?

Of course, other Financial metrics can be equally as tiring, since we can assign Profits to just as many Anythings as we can assign Revenue. Regardless of the compound metric, it almost always ends up as an actual measure of the denominator—Anything. As we learned to look for the denominators on our wall, the sales management code began to crack a little more easily.

Again, the most important takeaway from our examination of Financial metrics is the realization that we could not categorize a metric solely by the terms in its description. To accurately understand the value of a sales measurement, we must first determine what the number is actually intended to measure. These seemingly subtle distinctions will become quite important when we eventually get to the business of architecting a coherent and aligned system of sales force metrics.

The Case of the Disappearing Sales Pipeline

As we mentioned earlier in this chapter, Financial metrics (and in particular Revenue) are the lifeblood of any company. If ample revenue is not coming in the door to squeeze out some profit, then the door will eventually slam shut. And if the revenue coming in is sufficient to keep it open but insufficient to meet the company’s expectations, then that very same door becomes an exit for the company’s senior executives.

For that reason, executives cannot wait until revenue is actually in the door before they begin to watch it—they want it on the war room wall as soon as it appears on the horizon. It has therefore become incumbent on sales management to report anticipated revenue from in-process sales opportunities. They do so in an assortment of hypothetical financial statements known collectively as forecasts. Forecasts allow executives to gaze in the future, predict how much revenue will be coming in the door, and manage their stakeholders’ expectations appropriately. This keeps the doors open, but only as an entrance.

Without question, management’s favorite mechanism for real-time forecasting is the sales pipeline.1 Like Revenue, the sales pipeline really needs no introduction—every war room wall has some pipeline numbers on it. Appropriately, our study contained a good portion of metrics that were used to report the size, shape, and complexion of a sales pipeline. They included measures like these:

![]() Total Pipeline Revenue

Total Pipeline Revenue

![]() Number of Deals in Each Stage of the Sales Cycle

Number of Deals in Each Stage of the Sales Cycle

![]() Percentage of Deals Advancing by Stage

Percentage of Deals Advancing by Stage

![]() Days Length of Sales Cycle

Days Length of Sales Cycle

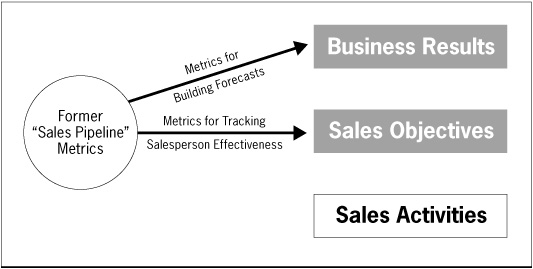

As we began to receive these metrics from our surveyed companies, we dutifully created a space on our wall for “Sales Pipeline” metrics. This category, we thought, was going to be the easiest of them all—if a metric had the term pipeline or sales cycle in it, then just throw it in the “Sales Pipeline” bucket. And conveniently, almost every company had already designated a category of pipeline metrics on its own, so it was a simple task for us to shuffle them to our sales pipeline space. But as we stared at these metrics over time, the pipeline numbers came to befuddle us.

Initially, we had the sales pipeline metrics in the “totally unmanageable” category that later became Business Results. This made sense because most all of the metrics in this category were quantified in dollars—Dollars in the Sales Pipeline, Dollars in Each Stage of the Sales Cycle, and so on. Of course, these dollars would eventually turn into Revenue, and we had already established that Revenue could not be managed. So sales pipeline metrics must be Business Results. Not manageable.

But once we created Sales Objectives as our third level of “influenceable” metrics, our eyes kept darting back and forth between those and our “Sales Pipeline” metrics like Percentage of Deals Won or Percentage of Deals Advancing. It would seem that a sales manager should be able to influence these metrics by coaching and developing her reps into more skilled sellers. In fact, if the sales manager could not influence metrics such as Percentage of Deals Won, then you’d have to fundamentally question the value of even having sales managers. Managers had better be able to influence the sales pipeline, or else their sales forces are in trouble.

Our suspicion that the “Sales Pipeline” category was too diverse kept nagging us, but objects at rest tend to stay at rest. Without any better way to characterize them, the Sales Pipeline metrics remained right where they were on our wall, as unmanageable Business Results.

They remained there until we had the epiphany that we discussed earlier: the metric itself is not as important as what it is intended to measure. We had fallen into the trap of letting the label on the metric define it for us. We needed to examine the nature of the metric to discover where it belonged on the wall. Finally, we had a new question that would help overcome the inertia of the Sales Pipeline metrics. So we began to interrogate the pipeline numbers with our new question, What are you really intending to measure?

It became quickly apparent that sales pipeline metrics have two distinct uses. The first intended use is to measure the health of the company looking into the future. These are metrics such as Total Pipeline Revenue or Weighted Value of the Pipeline, and they are typically reported at the corporate level. By assigning dollar amounts and probabilities to various milestones in its sales force’s aggregated opportunities, management can build a credible sales forecast for its overall organization. And this is the primary objective of these pipeline metrics on the war room walls—to create a probability-weighted financial statement that foretells good or bad future Business Results.

The second use of sales pipeline metrics is to measure the effectiveness of salespeople at moving opportunities through their sales cycles. These are measurements like Percentage of Deals Advancing or Percentage of Deals Won, and they are typically reported at the individual level. They are not intended to create financial statements like their corporate-level peers but rather are used by sales management as diagnostic and objective-setting tools to improve salesperson productivity. By identifying where a seller’s deals are getting stuck in the sales cycle, a manager can provide guidance or support to help the salesperson move further down the path to success.2

We therefore began to pull metrics out of the Sales Pipeline bucket and put them into one of two places (see Figure 3.5). Any metric that looked as though it was intended to measure the future health of the company remained at the Business Result level, but it was reallocated to the bucket of Financial measures where numbers like Revenue already lived. Whether it is booked Revenue or forecasted Revenue, the metrics both answer the same basic question: is this company healthy?

FIGURE 3.5 How the Sales Pipeline Category Disappeared

Any metric that was intended to measure the effectiveness of a seller at shepherding deals through his pipeline was moved to the Sales Objective level. Sales managers could then influence these measures through Sales Activities like coaching and training. We then breathed a sigh of relief, knowing that our management framework now allowed for sales managers to sway things like Percentage of Deals Won. But most important, our model now more closely resembled the reality that we knew.

So our breakthrough with the sales pipeline metrics was to separate the “forecasting” measures from the “salesperson effectiveness” measures. The forecasting metrics went into the Financial bucket within Business Results, and the effectiveness metrics went into a to-be-determined bucket within Sales Objectives. Our nagging concerns about the pipeline metrics had disappeared, but so had our “Sales Pipeline” category. We now had only three buckets within Business Results—Financial, Satisfaction, and Market Share. Life was much simpler. See Figure 3.6.

FIGURE 3.6 ![]() Business Results in Our Study: Financial

Business Results in Our Study: Financial

Satisfied Yet?

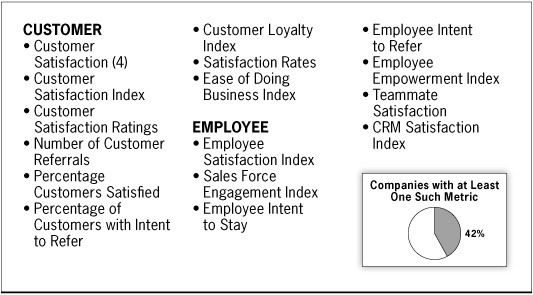

![]() As much as people like to think about themselves, they love to know what other people think about them. And though most individuals don’t go around routinely surveying their colleagues to assess their own likability, companies have a seemingly insatiable appetite for exactly that type of information. To a corporate entity, “likability” is commonly measured as “Satisfaction,” and we found that 26% of our Business Results metrics were some variation on this theme.

As much as people like to think about themselves, they love to know what other people think about them. And though most individuals don’t go around routinely surveying their colleagues to assess their own likability, companies have a seemingly insatiable appetite for exactly that type of information. To a corporate entity, “likability” is commonly measured as “Satisfaction,” and we found that 26% of our Business Results metrics were some variation on this theme.

Measures of Satisfaction are a different kind of health-check. They are the equivalent of “How healthy do I look to you?” There are two primary audiences for these cosmetic inquiries, both the company’s customers and its employees. Customer Satisfaction metrics constitute most of the Satisfaction numbers we saw, and they were quantified through measures like these:

![]() Overall Customer Satisfaction

Overall Customer Satisfaction

![]() Ease-of-Doing-Business Index

Ease-of-Doing-Business Index

![]() Percentage of Customers with Intent to Refer

Percentage of Customers with Intent to Refer

Leadership also cares greatly about the perceptions of its employees, and our research reflects this fact. In our data were employee-facing measurements like:

![]() Employee Satisfaction Index

Employee Satisfaction Index

![]() Employee Intent to Stay

Employee Intent to Stay

![]() Employee Engagement Index

Employee Engagement Index

Both categories of Satisfaction metrics shared a couple of similar qualities. First, they were both mostly calculated using indexes, rather than the units of percentages, dollars, or hours that quantify most other sales metrics. This is because satisfaction is a subjective and nonstandard measure that must be force-fit into a contrived scale, typically between one and five, that measures from “totally unsatisfied” to “totally satisfied.” We have seen companies actually attempt to convert Satisfaction measures into associated dollar amounts, but their success with the endeavor was questionable, at best.

The second similarity between the Customer Satisfaction and Employee Satisfaction metrics is that in both cases leadership collected both generalized and more focused measures of satisfaction. Two questions that exemplify the distinction would be “How satisfied are you with our company?” versus “How satisfied are you as a user of our CRM tool?” The second question is somewhat more tactical and could be more useful, depending on the company’s purpose for gathering the data. As a rule, the more specific a Satisfaction measure gets, the more practical it becomes as a management tool.

Like most of the numbers on our wall, Satisfaction metrics challenged us to find their rightful place in our management framework. The nature of their challenge was to identify whether satisfaction is a Sales Objective or a Business Result. At first we thought that measures of Satisfaction fit perfectly as Sales Objectives. If the sales force can do specific things to make customers more satisfied, then certainly that would drive increased sales and consequently increased revenue for the organization.

However, study after study has shown that the causal link between Customer Satisfaction and actual purchasing behavior is highly suspect.3 In the real world, customers might be quite satisfied with your products and your company, yet they can be lured away to a competitor for any number of reasons beyond your control. A colleague might convince them that your competitor has a better product, a superior may force them to switch allegiances, or a competitor’s salesperson might simply catch them in a moment of weakness. Regardless, Customer Satisfaction has not been definitively shown to drive purchasing behavior, so therefore it cannot credibly be considered a Sales Objective in our model.

Similarly, the direct impact of Employee Satisfaction on financial performance is annoyingly uncertain. Most research we have read confirms a correlation between Employee Satisfaction and organizational success, but it remains unproven whether happier employees cause a company to succeed or if a successful work environment makes for happier employees. Chicken → Egg → Chicken? Successful → Satisfied → Successful? We may never know.

Regardless, both Customer Satisfaction and Employee Satisfaction are unquestionably indicative of a company’s health. Whether or not happier customers and happier sales-people will improve financial performance is unclear, but unhappy customers and miserable salespeople simply cannot be a good thing. Therefore, we felt comfortable categorizing Satisfaction as a Business Result—a key indicator of company health, and something that must be purposefully influenced through the management of certain Sales Activities and their related Objectives.

We have a bit of a love-hate relationship with satisfaction surveys. On the love side, we view them as useful vehicles to collect candid feedback that might otherwise go unheard by management. One might expect the sales force to be an effective communication channel for customer feedback, but salespeople can actually serve as an unintentional filter for valuable customer insights. Ironically, we find that salespeople are often blind to burning customer issues—even when the blaze is plainly visible to others.

There is a “Curse of Intimacy” that sometimes settles on a sales force that enjoys long-term relationships with its customers. After years of repeated interactions, salespeople can become numb to subtle signals from their customers that would be completely apparent to a bystander. Further, intimacy can breed the false assumption that customers will openly reveal all of their concerns to their salesperson. Sellers will often say, “I don’t need to constantly ask that customer how we’re doing. I’ve known him for 20 years, and I talk to him every week. If he has a problem with us, he’ll let me know.” Maybe.

To provide a possibly familiar example of being ambushed by the Curse of Intimacy, I had a friend many years ago whose girlfriend brought their relationship to an abrupt end. Totally unexpectedly, she announced that she was terminating the friendship—immediately. After the obvious interrogation, it became apparent that there were no other contributing factors. She simply was unhappy in the relationship and had decided that it was time to get out.

By his account her actions “came out of nowhere,” and yet, though I am not the most perceptive person in the world, it was pretty obvious to me that their relationship had been going downhill for a while. In fairness to my friend, it is hard to notice stuff like that when you’re too close to the action, and that is exactly where most salespeople find themselves with their very best customers—extremely close to the action. While maintaining clear communications with your best customers is absolutely critical, intimacy can actually inhibit the flow of meaningful information and deaden a seller’s awareness to otherwise apparent signs of trouble.

From this perspective, satisfaction surveys are intuitively appealing. They give customers, or in some cases employees, the opportunity to provide candid feedback in a sterile, non-threatening environment. Surveys are also relatively low-cost, so they enable data collection on a scale that is useful for analysis. They therefore can be a safe and productive path around the Curse of Intimacy. But there is one big pothole on that path that counterbalances our love-hate quotient.

A little data is a dangerous thing. Though one might tend to believe that any data is good data, gathering insufficient or inaccurate data is far worse than gathering no data at all. A theme of this book is that when good metrics are used properly, they provide managers with the insights to make good decisions and the ability to drive change. Conversely, inadequate or misinterpreted data can cause the wrong decisions to be made, which can have a devastating effect when the wrong kind of change is implemented.

Most satisfaction surveys fall into the territory of inadequate information from a management perspective. This is because they provide only an averaged index number that has no objective value and little direct relationship to the practical world. If your company makes $100 million in profit, you know exactly what that means: your company now has 100 million more dollars in the bank than it did last year. And if you want to make $50 million more in profit next year, you know exactly what you have to do—increase your revenues or decrease your costs.

But if your customers are 4.6 satisfied, what does that mean? And if you want to raise their Customer Satisfaction to 4.9, how would you do that? This is why we refer to satisfaction indexes as applause-o-meters. Hearing your customers clap for you feels pretty good, but you can’t be sure that it’s loud enough, since there’s no objective comparison for applause. And you’ll always want to move the needle higher, but it’s hard to know what compels each person to clap. Are your customers all clapping in unison, or does each have her own reasons for being satisfied? It’s hard to know from a single, averaged, indexed number. Satisfaction indexes can be a lot of fun to watch, but they’re difficult to understand.

So Satisfaction metrics can be useful as directional indicators of a company’s health. Figure 3.7 shows the many forms these metrics take. They also allow management to leapfrog organizational information filters and gather candid feedback from its customers and employees. However, measures of Satisfaction must be kept in perspective. Like other Business Results, they are driven by many other things in an organization, and you must take care to decipher their meaning before making any management decisions. But unlike other Business Results, Satisfaction metrics are difficult to interpret because they are artificial constructs with ambiguous units of measure. So feel free to enjoy the applause, but get to know your audience to make certain you understand why they clap. Or why they boo.

FIGURE 3.7 ![]() Business Result Metrics in Our Study: Satisfaction

Business Result Metrics in Our Study: Satisfaction

Dare to Share

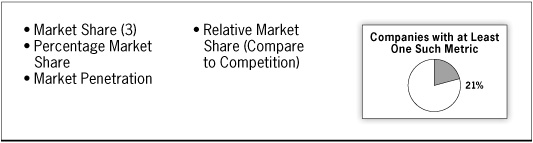

![]() The final category of Business Results that we found in our research is Market Share. Almost always expressed as a percentage, this number is the portion of the total addressable market for your products or services that you have captured relative to your competitors. It is Share of Wallet on the grandest scale—all of the wallets. This is an age-old marketing metric that can seem a bit sleepy, but we have actually seen some interesting dynamics surrounding this measurement.

The final category of Business Results that we found in our research is Market Share. Almost always expressed as a percentage, this number is the portion of the total addressable market for your products or services that you have captured relative to your competitors. It is Share of Wallet on the grandest scale—all of the wallets. This is an age-old marketing metric that can seem a bit sleepy, but we have actually seen some interesting dynamics surrounding this measurement.

In some industries like consumer products or certain industrial materials, this metric is nearly on par with Financial metrics, since the two categories are so tightly intertwined. We have worked with clients that saw Market Share as so important to their profitability that it was included in their salespeople’s incentive compensation plans. In some cases, gaining significant market share even trumps profitability, as we witnessed in the dot-com boom when companies were trying to establish a “first mover advantage” at any cost. Capture enough Market Share, and the riches might eventually follow.

We have also worked with clients whose overarching goal was to keep Market Share as steady as possible. These are typically mature industries in which the competitors have settled into comfortable market positions and don’t want to rock the boat. Like two dogs that previously met in a park and wrestled to establish dominance, their major battles have largely been fought, and it is desirable to avoid additional skirmishes. If one company begins to gain meaningful Market Share, a price war could ensue that would damage the entire industry’s profitability. Status quo is the way to go.

And finally, we have worked with companies for which getting Market Share numbers from the leadership team was more difficult than getting their Social Security numbers and mothers’ maiden names. These companies have market share so large that they effectively rule their industries. In these rare situations, advertising their dominance could draw unwanted attention from various entities that could threaten their market positions. We’ve known other companies that don’t fear external interference, but they want their employees to behave as if they are scrappy start-ups, despite their substantial market heft. In cases such as these, success is quietly celebrated and loudly ignored.

One way in which we have seen companies struggle with Market Share is in calculating their total “addressable” market. Market Share numbers can be greatly influenced by how widely you cast your net. For example, if you are a $250 million player in a $1 billion industry, then your Market Share is nominally 25%. However, if you decide that $500 million of the industry is captive to a competitor and does not represent any real opportunity for your company’s products, you might decide that only $500 million of that market is “addressable.” Consequently, you could calculate your share as $250 million of a $500 million market, or 50%.

Math such as this might seem like an academic exercise, but many companies use these kinds of assumptions to size and deploy their sales forces. Taking the example we just used, you could potentially need only half as many salespeople to cover the marketplace if you decided to concede $500 million of it to your competitor. Or you might need to double the size of your sales force if you determine that the addressable market is actually $2 billion. So you can see how resource allocation and other critical management decisions can be affected by determining what your addressable market truly is.

Regardless, Market Share is a key measure of a company’s health in many industries. Though it might appear exceedingly unpopular with only 8% of our Business Result metrics falling into this category, we can assure you that a higher percentage of companies are tracking Market Share data. In fact, marketing departments in most companies will have this number on the tips of their tongues, but our study only incorporated sales force metrics. At the highest level of many organizations, corporate health is all relative. See Figure 3.8.

FIGURE 3.8 ![]() Business Result Metrics in Our Study: Market Share

Business Result Metrics in Our Study: Market Share

THE PROBLEM WITH “MANAGING BY RESULTS”

Though Business Results clearly are not manageable by any direct means, this does not keep sales managers from trying. Week after week across the globe, sales managers meet with their sales forces to review their salespeople’s “numbers” and to provide the sellers with counsel on how to improve them. It would be impossible to estimate how many times we’ve heard variations of this conversation between a sales manager and a rep:

Manager: So let’s take a look at how you’re doing year-to-date with your numbers.

(Manager and rep stare at a pipeline report, which is the agenda for their discussion.)

Rep: Unfortunately, you can see that I’m falling behind in my Revenue numbers. I don’t know if I’ll be able to make my $1 million target for this quarter, and that’s going to put me even further behind for the year.

Manager: Yes, I see that. How are you going to get that Revenue number back in line?

Rep: Well, I have a pretty big pipeline of business that I’m working right now.

Manager: Good. How big is your sales pipeline?

Rep: I have about $4 million in there that could potentially close by the end of the year.

Manager: But you’d have to win more than 50% of that to make up the ground that you’ve lost so far this year. That would be a pretty high win rate by historical standards.

Rep: Yeah, I guess you’re right about that.

Manager: Your pipeline needs to be bigger. It should probably be more like $6 million, if you’re realistically going to hit your quota.

Rep: Yes, that would make sense.

Manager: Do you think you can pump up your pipeline over the next few weeks?

Rep: I think so. I’ll just have to work a little harder at it.

Manager: You can do it. Get that pipeline number up, and you’ll get to your quota. I believe in you.

Rep: Thanks. I’ll hope to have better news by the end of the month.

Manager: Great. Good luck.

What you have just witnessed is “managing by results.” Revenue and the size of a pipeline are both Business Results and cannot be directly managed. This conversation is the business equivalent of your doctor saying to you, “You’re not looking too healthy. You’d better go get more health, or else you’re not going to be healthy the next time I see you.”

It’s not a productive management practice to examine a Business Result and then direct the salesperson to go change the Business Result. A more productive conversation would help sales reps select the Sales Objectives that will steer them in the right direction and then set expectations for the Sales Activities that will lead them there.

That same conversation would have been more helpful if it had ended something like this:

Manager: Your pipeline needs to be bigger. It should probably be more like $6 million if you’re realistically going to hit your quota.

Rep: Yes, that would make sense.

Manager: So what are some options for increasing the size of your pipeline?

Rep: Well, there are only a couple of options. I could either get more opportunities in my pipeline, or I could find bigger deals [two examples of Sales Objectives].

Manager: I agree. Which of those objectives seems the more achievable of the two?

Rep: I don’t think I can physically pursue many more opportunities because I’m already working as hard as I possibly can. I suppose I’ll need to go after bigger deals.

Manager: Good. So how would you go about doing that?

Rep: I could focus on selling our premium product line, since it’s priced about 50% higher than our other products [another Sales Objective].

Manager: I like the idea. So what do you need to do over the next month or so to get larger deals in your pipeline?

Rep: I need to stop calling on smaller companies and redirect my prospecting effort toward bigger ones [a Sales Activity], probably companies with more than $100 million in revenue, because they’re the ones that find real value in our more sophisticated products.

Manager: I think that sounds like a great plan. Can we set a goal to have 50% of your pipeline in premium products with companies larger than $100 million by the end of next quarter?

Rep: Sure. I think that’s doable.

Manager: Super. Go get ’em.

In this second conversation, the sales manager didn’t just tell the salesperson to “get more Results,” she helped the rep think through which Sales Objectives were most likely to get them the Results and what changes in Sales Activities were required to achieve them. This transition from management by results to management of activities is how sales managers take control of their sales force’s performance. Management stops begging for outcomes and starts directing the behaviors that will cause a chain reaction from Activities to Objectives to Results.

We therefore need to take our examination down a level, to explore how Sales Objectives can help us drive toward our desired Business Results.

STATUS CHECK

We had now begun to dig into the management code by examining the level of metrics that cannot be managed whatsoever, Business Results. Eventually, these metrics all fell into one of three categories:

1. Financial, which are primary accounting measures like Revenue and Profit (note that these can be reported as either forecasted or realized dollars)

2. Satisfaction, which are measures of customer and employee pleasure with certain aspects of a company, its products and services, or its relationships (aka the applause-o-meter)

3. Market Share, which are measures of a company’s captured portion of its total addressable market

These metrics on the war room wall are really measures of overall corporate health: how healthy the company considers itself, how healthy key stakeholders find it, and how healthy it looks in comparison to its peers. In sum, they determine how well a company is doing. If you have lots of happy, profitable customers, then you are doing well, for sure.

Our examination of Business Results led us to realize that the true nature of a metric is determined by its intended use. Using this conclusion, we eliminated our troublesome Sales Pipeline category entirely and redistributed those metrics to other spots on the wall. If the pipeline metrics were used to forecast financial performance, then into the Financial category of Business Results they went. If they were intended to measure a salesperson’s effectiveness in moving deals through the pipeline, then they were diverted to Sales Objectives.

Of course, as high-level corporate outcomes, Business Results cannot be directly managed. To exert any form of control over these numbers, leadership needs to select the right Sales Objectives and manage the right Sales Activities to drive its desired outcomes. See Figure 3.9. We therefore turned our attention to the next challenge in engineering a cohesive set of management metrics—understanding how to identify and measure relevant Sales Objectives.

FIGURE 3.9 Business Results with Corresponding Metrics