Stacking emotional layers in short cinematics.

This chapter shows

ways to make both in-game and pre-rendered cinematics more artful and, thereby, more emotionally complex and powerful.

When you talk about writing in games, some designers think you're speaking only about cinematics.[1]

Of all the ways to evoke emotion, however, cinematics are the least game-like portion of any game. That's not a criticism, just a fact. Still, they play a role in many games and probably will for some time to come.

In some games, they serve powerful functions:

To set the tone of the game in the beginning or to establish the story itself

To establish a particular character

To establish the game's world and its backstory

To bridge the story from the last game, if the game is a sequel

To bridge one section of the game to the next

To reward a player for making it to a certain point in the game

Two categories of Emotioneering deal with cinematics. We'll examine one here and the other in Chapter 2.32, “Opening Cinematic Techniques.”

Because cinematics are, in effect, short films, every single technique that factors into writing great films also applies to cinematics. This includes creating unique characters, riveting dialogue, compelling scenes, and so on.

Poorly written cinematics can be:

Wooden

Corny

“On the nose” (people saying their feelings directly instead of hinting at them)

Amateurish due to many other factors, described next

Here are a few guidelines for writing riveting cinematics.

When one is writing in screenplay format, with the dialogue in a column in the middle of the page, I call a block any time there are three or more lines (not sentences) in a character's dialogue. Minimize these blocks or your characters will sound like they're making speeches, not conversing. An exception might be in a formal or informal debate.

Characters should possess a colorful grouping of personality Traits that determine their dialogue and their actions (a Character Diamond). To learn about creating colorful Character Diamonds, see Chapter 2.1, “NPC Interesting Techniques.”

It's okay, in a cinematic, for a character to have mixed feelings about another character. For instance, a character could feel, simultaneously, both appreciation and annoyance toward a second character.

Or, instead of simple ambivalence, you can make the relationships between characters even more complex with this next technique:

Layer Cakes mean that Character A has various layers of feelings toward Character B. These varied feelings can present themselves either simultaneously or sequentially. For a full description of how to create Layer Cakes, take a look at Chapter 2.8, “NPC Toward NPC Relationship Deepening Techniques.”

“You won't get away with this!” is clichè and bland. “How's it going?” is bland. Such lines are fine for the first draft or two. But try to avoid any such lines in a cinematic.

This one in particular will become more and more important as our ability to animate facial expressions in games improves.

Conversations rarely stick to a single topic. Instead, they tend to weave in other strands, some of which never go anywhere. However, with cinematics currently being so expensive to produce and players' eagerness to get on to gameplaying always present, your cinematics might not be able to benefit from this writing technique.

Either have the player be unable to predict the outcome of the cinematic, or else be unable predict the way that outcome is achieved.

This is especially true if the obstacle or interruption comes at a seemingly inappropriate time, such as when two people are arguing.

The first example scene was written by one of my students (a beginner at the time, who asked me to rewrite it). It deals with the first women to join the Navy, which occurred in WWII. It's reprinted here with her permission. (She has, by the way, gone on to become quite an accomplished screenwriter.)

note

Although neither version of the scene in this chapter would necessarily end up as a cinematic in a game, the techniques used in the rewritten version are applicable to almost all cinematics.

The original scene lacks many of the specific techniques that could enrich the scene's flow, the characters, their relationship to one another, and their dialogue.

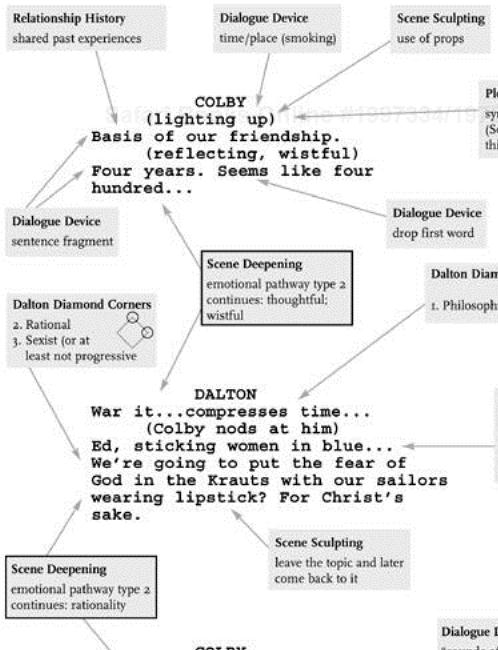

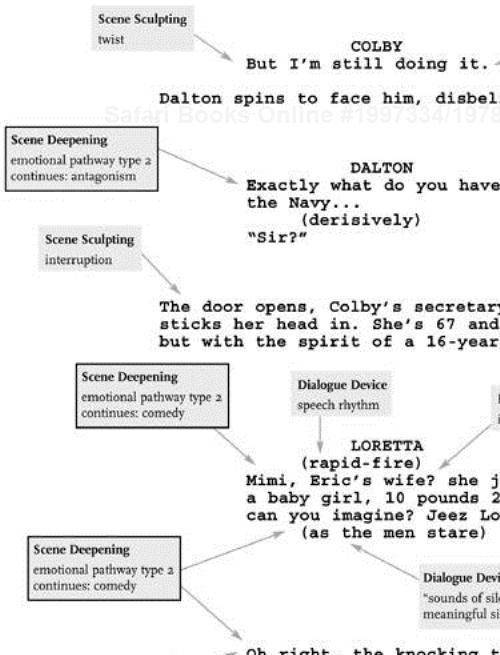

I then rewrote the scene, using not just the techniques listed previously in this chapter, but many additional ones as well.

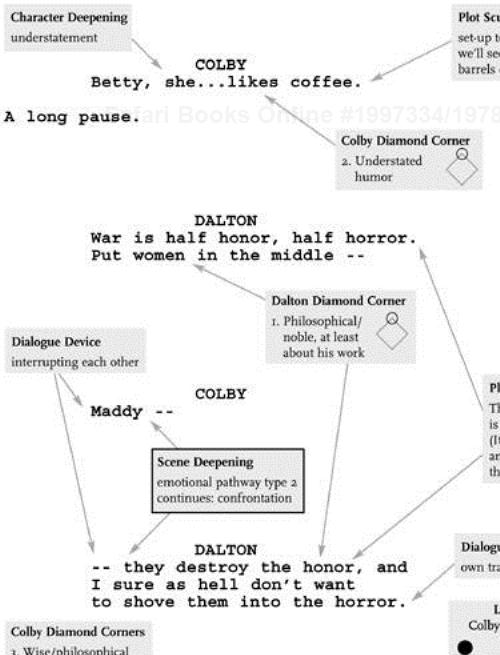

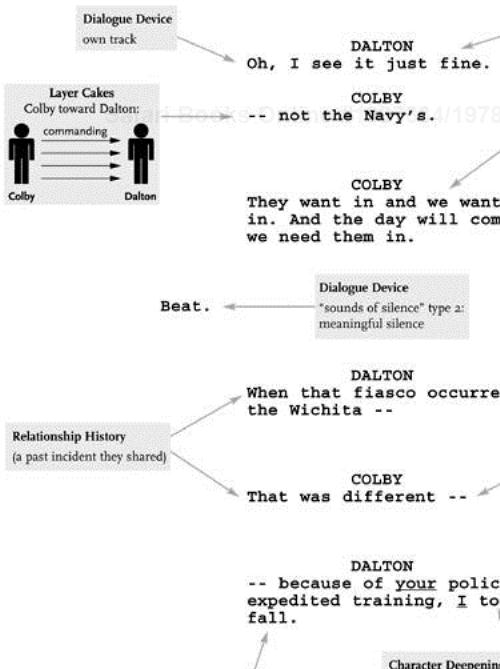

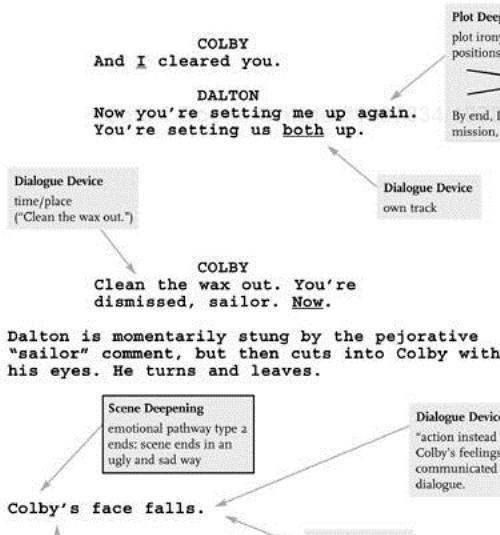

The third version is the same as the second, but points out every single technique I used. You'll find there are quite a few. It's dissected with many drawings and explanations as to exactly why certain artistic choices were made, and which writing technique or techniques have been employed.

Writing riveting cinematics requires a wealth of screenwriting techniques, far too extensive to enumerate. However, you'll be introduced to a minor cornucopia of techniques in the third version.

note

There are many terms used in the third (deconstructed) version of the scene to describe the screenwriting techniques that have been used. These terms aren't used anywhere else in the book. Therefore, the last portion of this chapter contains a glossary of these terms. Most of them are only defined here, and not in the glossary at the end of the book.

You'll find that the rewritten scene is longer than the original. Because I rewrote the scene for the purposes of demonstration, I crammed into it tons of techniques. In a real cinematic, you might want to use only a portion of the techniques that are used here.

The following is the original scene, written by one of my students.

INT. ADMIRAL COLBY'S INNER OFFICE - DAY Plush oak, immense. At his desk, ADMIRAL JASON COLBY calmly continues writing. VICE ADMIRAL MADISON DALTON stands. COLBY I'm not backing down, Maddy. DALTON Women do NOT belong in MY navy. COLBY Your job is to recruit 900 potential women officers in the next 90 days. DALTON We're in the middle of a war for God's sake. COLBY Admiral James Madison Dalton, are you contradicting a superior officer? DALTON No, Sir, but... COLBY But, nothing, Maddy. You know how to recruit and train better than anyone and we're in a hurry with this thing. Surely someone named for a president can handle training a few women. DALTON Give this to McNary. They can all fail together. COLBY I'm a patient man, but... (booming voice) Get the hell out of here and that's an order! DALTON This is an invasion.

This version of the scene conveys information, but neither the characters, their relationships, their dialogue, nor the scene itself are sufficiently compelling nor emotionally layered.

Consider the same scene after my rewrite:

INT. ADMIRAL COLBY'S INNER OFFICE - DAY Plush oak, immense. At his desk, ADMIRAL JASON COLBY calmly continues writing. VICE ADMIRAL MADISON DALTON stands. COLBY I'm not backing down, Maddy. DALTON Ed, what do you like most about the Navy? COLBY Like? He thinks for a few seconds. COLBY Gotta be the grub. Both he and Dalton smile. DALTON See? And I always thought those stripes drained a man of his humor. COLBY (smiles) Love to chat, but Bertrand's due here at three. (pulls out a cigarette) Match? DALTON (tosses him some matches from his pocket) Four years I've never seen you carry your own matches. COLBY (lighting up) Basis of our friendship. (reflecting, wistful) Four years. Seems like four hundred... DALTON War it...compresses time... (Colby nods at him) Ed, sticking women in blue... We're going to put the fear of God in the Krauts with our sailors wearing lipstick? For Christ's sake. COLBY (takes a drag; seriously considers) Got a point. DALTON Good. He turns to leave. COLBY But I'm still doing it. Dalton spins to face him, disbelieving. DALTON Exactly what do you have against the Navy... (derisively) "Sir?" The door opens, Colby's secretary LORETTA sticks her head in. She's 67 and frail-looking, but with the spirit of a 16-year-old. LORETTA (rapid-fire) Mimi, Eric's wife? she just had a baby girl, 10 pounds 2 ounces can you imagine? Jeez Louise -- (as the men stare) Oh right, the knocking thing. But I know how much you like her and Eric so I thought you'd want the skinny. A quick smile, her head disappears, and the door closes. COLBY Betty, she...likes coffee. A long pause. DALTON War is half honor, half horror. Put women in the middle -- COLBY Maddy -- DALTON -- they destroy the honor, and I sure as hell don't want to shove them into the horror. COLBY For once, Maddy, you've gotta pretend to be a bigger man than you are. Can't see the future? That's your problem -- DALTON Oh, I see it just fine. COLBY -- not the Navy's. COLBY They want in and we want them in. And the day will come when we need them in. Beat. DALTON When that fiasco occurred on the Wichita -- COLBY That was different -- DALTON -- because of your policy of expedited training, I took the fall. COLBY And I cleared you. DALTON Now you're setting me up again. You're setting us both up. COLBY Clean the wax out. You're dismissed, sailor. Now. Dalton is momentarily stung by the pejorative "sailor" comment, but then cuts into Colby with his eyes. He turns and leaves. Colby's face falls.

As mentioned earlier in the book, some people have a desire to find a “magic pill” that produces masterful writing. This desire for a simple fix doesn't happen just among game designers. I've seen various trends sweep through Hollywood, as executives or writers searched for just such a surefire formula.[2] They'll grasp onto one for a time until they realize it doesn't produce predictable hits, and then abandon it, only to scramble for the next theory.

The solution isn't a formula. The solution is to start with a strong premise, structure the story well, come up with inventive plot twists, and then add techniques that, one by one, steadily enhance the artistry and emotional impact of the writing. The richness of writing comes from Technique Stacking.

The first of the three scene samples was weak not because the writer was “bad,” but because the writer didn't know and didn't apply all those techniques that were integrated into the next version.

There is no magic pill. As with painting or programming, becoming an accomplished writer takes time and study. And, as in any artform, the day will never come when even the best writer still can't improve.[3]

By the way, remember that the following Glossary explains all the terms used in the “deconstructed version” of the scene.

As you go through the third version, some of the terms like Character Diamond Corner will be familiar to you from reading this book, for you've already learned about the corners (the different Traits) of a Character Diamond. You'll also be familiar with Layer Cakes. (These terms, however, are also defined in the following glossary.)

Other terms will be self-explanatory. But following are a few that you might need to know to make sense of it. They're listed here in alphabetical order.

Bit Character. A character who only has several, or maybe even just one, line in the game.

Character Arc. The rocky path of growth a character undergoes in a story, usually unwillingly, during which the character wrestles with and eventually overcomes some or all of a serious emotional fear, limitation, block, or wound (FLBW). Examples: a character who is overcoming a lack of courage or a lack of ethics, or who is learning to love or take responsibility for others, or who is overcoming guilt.

Character Deepening Technique. A technique that gives a character a feeling of emotional or psychological depth or complexity.

Character Diamond. A colorful grouping of personality Traits that determine the character's dialogue and actions. To learn about creating colorful Character Diamonds,[4] see Chapter 2.1, “NPC Interesting Techniques.”

Chemistry Technique. A technique to make it feel like two characters have Chemistry—i.e., that they belong together as friends or lovers. (For more on Chemistry Techniques, see Chapter 2.7, “NPC Toward NPC Chemistry Techniques,” and Chapter 2.11, “Player Toward NPC Chemistry Techniques.”)

Crossing the Dramedy Line. Crossing briefly from drama into comedy, or vice versa.

Diamond Corner. A corner or Trait from a Character Diamond. (See Character Diamond.)

Drop First Word. When you drop the first word in a character's line of dialogue.

Emotional Pathway Type 2. When the scene takes us through many different emotions in a quick period of time.

Flipping a Scene. The scene flips and goes the opposite direction it was going earlier. (For instance, the lovers start out by kissing and end by fighting.)

Layer Cakes. When Character A has various layers of feelings toward Character B, and these varied feelings can present themselves either simultaneously or sequentially.

Own Track. When a character completely ignores what the other character is saying, and continues on the same subject he or she was initially speaking about. The character stays on his or her “Own Track.”

Plot Deepening Technique. A technique that gives emotional depth to a plot.

Plot Sculpting Technique. A technique that makes plots more interesting.

Ragged Ending. When a scene ends in an unhappy, ugly, or uncomfortable way.

Relationship History. Anything that gives us the feeling that the characters share a common history.

Scene Deepening Technique. A technique that gives emotional depth to a scene.

Scene Sculpting Technique. A technique that makes the scene more interesting. It makes the scene flow in interesting ways, or begin or end or unfold in interesting ways.

Sentence Fragment. When you drop out two or more words from either the beginning, middle, or end of a character's line of dialogue.

Set-Ups and Payoffs. Something—an object, a phrase spoken by a character—is introduced early in the plot. When it's introduced, it's a set-up. A set-up is revisited in an interesting way one or more times later in the story. Each of these instances is a payoff.

Example: Early in a story, the character puts a child to sleep by reading aloud a story about a sweet little kitten (the “set-up”). Later in the story, the character is attacked by 1,000 rabid cats (a payoff).

Another example: Early in a game, your character (the one you play) learns to throw a Frisbee (the set-up). Later in the game, the character's life will depend on being able to throw a circular, Frisbee-like weapon (the payoff).

Slam. An incident in a scene, which may comprise an entire scene, which forces a character to wrestle with his or her fear, limitation, block, or wound (FLBW).

Example: A gunslinger who is just out for himself (his “limitation”) would experience a slam when he suddenly finds that he has to defend an entire community from an enemy (which means he'd have to take responsibility for others).

After enough slams, a character usually grows through his or her Character Arc and overcomes his or her FLBW. In this example, the gunslinger's Character Arc would be to overcome selfishness and learn to be responsible for others.

Symbolic Subplot. An object or action that represents the character's growth through his or her Character Arc. (See Chapter 2.23, “Enhancing Emotional Depth Through Symbols.”)

In the rewritten scene, smoking represents Admiral Colby at his best—he smokes during those parts of the story when he has the vision and courage to bring women into the Navy. As the story progresses, Vice Admiral Dalton, originally so resistant to the idea, will become its champion. Colby, originally far-seeing, will become conservative and even reactionary. He'll try to stop the plan he put in motion.

As he falls away from his progressive ideals, he gives up smoking. So we set up the symbol that smoking = Colby at his best.

(Most viewers' and gamers' expectation would be that Colby would stop smoking [a healthy act] as his views evolve, not as he loses his progressive ideals. However, it's often more artful and interesting to go against expectations.)

Of course, some might think a more normal use of smoking at a symbol would be for Colby to be smoking while at his worst, and then stopping when he grows to become visionary.

But since that would be the obvious route, let's “find the cliché and then throw it away,” as I tell my screenwriting students.

Time/Place. Something that gives us a sense of the time and place in which the scene or cinematic is set.

[1] A cinematic is a section in a game that is like a very short movie. The player loses control of the game and watches passively. Cinematics can range from a few seconds to a few minutes.

There are currently no consistent terms for these cinematics. Cinematics animated or filmed separately from the game and then later integrated into the game are called pre-rendered cinematics, FMV (full-motion video), cut scenes, or CG cinematics (computer graphics cinematics). Cinematics created with the game engine are called in-game cinematics, in-engine cinematics, in-game-engine cinematics, or real-time cinematics. Some in-game cinematics permit the player to control the camera angle.

To say that an in-game cinematic is created with the game engine necessitates that we define game engine as well. A game engine is code that makes a game run, renders what you see in the game, renders the audio, governs the use of the controller, and operates all other systems that make the game function. Some (but by no means all) in the game industry also use either the term rendering engine or renderer for the code that renders what you see in a game, and say that the rendering engine or the renderer is a subset (or part) of the game engine.

[2] Among accomplished writers, this rarely, if ever, happens. They realize all too well the wide array of techniques that they need to integrate into an artful film or television episode.

[3] I have a group of friends, all of whom are professional writers (and my former students), that regularly gather to analyze our favorite films and great classics on DVD. We stop the films every few minutes to identify and analyze the techniques being used. There simply is never a time when there's not room for the expansion and deepening of one's craft.

[4] The grouping of Traits is called a Diamond because, quite frequently, the character has four major Traits, or corners, for his or her Diamond. For instance, if a character's main personality Traits are: (1) offbeat humor, (2) badass attitude, (3) protective toward the oppressed, and (4) a philosophical side, these would be the four corners of the character's Character Diamond. Though four corners is common for major characters, three or five can also work for major characters.