7

Psychoanalytic Analysis

The 2011 film Drive revolves around the mysterious Driver (Ryan Gosling), a movie stuntman in modern Los Angeles whose choice to moonlight as a getaway car driver for some local crooks eventually attracts the attention of more dangerous individuals. The Driver dreams of leaving his questionable occupations for the glories of the Formula 1 racetrack, but he does nothing to change his circumstances until he meets a single mother named Irene (Carey Mulligan). When a powerful crime lord threatens to kill Irene and her son over her ex‐husband’s debts, the Driver attempts to protect them, initially by trying to raise funds through a heist, and later by systematically killing everyone involved in the crime lord’s local syndicate. The film ends with the mortally wounded Driver cruising out of Los Angeles after killing the last of the men who threatened Irene. While his fate is certainly sealed and he will never see Irene again, he appears to take some solace in the knowledge that she and her son are finally safe from harm.

The film’s title is a double entendre. On the one hand, it clearly refers to the Driver’s legal and extra‐legal occupational talents, as well as his original means of escaping an unfulfilling life. On the other, drive is also a fitting synonym for the compulsion the Driver demonstrates in relation to Irene, a woman he hardly knows but to whom he feels a profound and ineffable connection. As the narrative of the film unfolds, it becomes clear that the Driver is, in fact, the one being driven, compelled by some unknown force to compromise his well‐being in order to preserve Irene’s. As viewers watch the Driver transform from a criminal accessory to a single‐minded, animalistic killer, it seems pertinent to question if he ever had as much control over his decisions as his enigmatic name suggests.

The title’s double meaning would be no surprise to scholars who utilize a Psychoanalytic approach to study the media, for the idea of an unsettling drive that seeks satisfaction without regard to safety or reality forms the theoretical core of Psychoanalytic theory. The Austrian psychiatrist Sigmund Freud originally proposed his theory of the drives in order to explain human psychological motivation, and Psychoanalytic media scholars explore how media texts reflect these powerful forces. Though the body of knowledge in this tradition has changed considerably over time, one could say that the approach is generally grounded in the genesis of individual psychology, the psychology of the media text, and the ways in which the two interact in the process of media consumption.

The first half of this chapter outlines the major tenets of Psychoanalytic theory, as well as the two major models of human mental development that have heavily influenced media studies (Freudian and Lacanian). The latter half traces the historical inception and evolution of Psychoanalytic theory, largely in the realm of film studies. For reasons that will become apparent, the vast majority of Psychoanalytic work in media studies has concentrated on film. However, we conclude this chapter by considering recent Psychoanalytic work that also extends this branch of theory beyond the cinema.

Psychoanalytic Theory: An Overview

Psychoanalytic theory may be distinguished from other theories of psychology by the existence and centrality of the drives, or “somatic demands upon the mind.”1 In other words, while other branches of psychology are primarily concerned with the influence of external phenomena on mental structure (i.e. behaviorism, social psychology, etc.), psychoanalysis begins with a consideration of how the mind registers the body’s internal, biological needs (for nutrition, comfort, sex, etc.) and transforms them into motivating forces, or drives. Different drives arise from different sources and seek out different objects in the world, but all of them ultimately seek satisfaction through the achievement of these objects, a maxim that Freud refers to at times as the pleasure principle.2 The motivating force of hunger, for example, arises from biological needs for nutrition and can be satisfied through the ingestion of edible objects. The sexual drive arises from biological needs for sex and can be satisfied through contact with stimulating objects. Importantly, these examples suggest that the object(s) of a drive and the kind of satisfaction it seeks are highly variable, differing from person to person. One person may find a given object intensely satisfying (chocolate, for example, in relation either to nutrition or to sex), while another may find that the same object provides no satisfaction whatsoever. A person may even seek out an object that others find decidedly nonsexual in order to satisfy an explicitly sexual drive (e.g. feet, uniforms, etc.). Here, we do not mean to imply that people choose these objects or know why they provide satisfaction. Very often, people cannot explain these types of attractions, and we will address the source of this inexplicable variability in a moment. For now, it is most important to realize that it is the variability of objects and aims that distinguishes drive from hard‐wired instinct. Freud’s theory of the drives attempts to account for the wide variety of motivating tastes and practices that we see uniquely manifest among human beings.

The complicated variability of objects and aims also means there is ample opportunity for the drives to be halted in their attempts to find satisfaction. What if people cannot financially afford the specific objects that would seem to satisfy their drives? What if the given object of a drive is socially unacceptable, or possession of the object is punishable by law? Unfortunately, the motivating force of the drives does not diminish or disappear in these circumstances. Instead, the drives become frustrated, repressed, or sublimated (redirected into easier or more socially acceptable channels). Freud refers to this constant curbing of the drives according to possibility, law, or social convention as the reality principle, and in the interplay between pleasure‐seeking and the realistic limits placed on this activity, human mental structure is born.

In order to explain the interplay between drive and reality, Freud proposes two different topographies (or maps of mental life) in his work. Neither is more “correct” than the other; each simply sheds light on different aspects of the interplay. Freud proposes the primary topography in his first major book, The Interpretation of Dreams: the unconscious, pre‐conscious, and consciousness.3 When a drive becomes blocked in the achievement of its object for any of the various reasons just outlined, Freud suggests that the mind copes with this frustration by repressing or submerging the wish for the object into the unconscious, a mental screen behind which the individual cannot clearly or knowingly see. The relationship between drives/wishes and the unconscious is less like a penny in a piggy bank and more (to borrow a metaphor from Freud) like an iceberg in the ocean. The ocean does not neatly “contain” the iceberg, but it does mask the majority of it from view. Repression, or the immersion of a drive beneath the unconscious, temporarily relieves the sense of frustration, but the drive always waits for an opportunity to make itself known again in either the pre‐conscious or consciousness. The pre‐conscious is the link between the unconscious and consciousness, and through it repressed drives most commonly bubble up to consciousness in the form of dreams. In fact, Freud suggests that we very often “get what we want” in our dreams because they regularly originate from repressed drives. Should a dream be so intense that the dreamer remembers it upon waking, the drive becomes somewhat known to consciousness, though often obscured beneath layers of dream symbolism. The drive may also come to manifest in conscious life as so‐called “Freudian” slips of the tongue or as otherwise unexplainable medical symptoms that symbolize fixations on wished‐for objects.

At this point, you may be asking: But where do the drives originate in this schema, and what manages their repression? Freud’s second topography, involving the id, ego, and superego, helps to clarify these questions.4 The id is the part of the mind present from birth, the source of the drives regulated by the pleasure principle. The ego is an outcropping of the id, the part of the id closest to consciousness, which develops as the individual becomes aware of reality. As such, the ego is responsible for curbing the drives according to the reality principle. As Freud explains:

[I]n its relation to the id [the ego] is like a man on horseback, who has to hold in check the superior strength of the horse; with this difference, that the rider tries to do so with his own strength while the ego uses borrowed forces. The analogy may be carried a little further. Often a rider, if he is not to be parted from his horse, is obliged to guide it where it wants to go; so in the same way the ego is in the habit of transforming the id’s will into action as if it were its own.5

We can see in this analogy that the drives of the id remain powerful motivating forces despite the limitations brought upon them by the ego. At its strongest, the ego is able to repress a drive temporarily, but more often it must settle for sublimating or channeling the drive into more acceptable objects and aims. In this way, a person who yearns for a socially unacceptable object of the sexual drive (an animal, for instance) may settle for a more acceptable, approximate object instead (like a sex toy). Similarly, just because we cannot eat delicious food at all hours of the day does not mean that we give it up entirely. We satiate our hunger by dividing our eating habits into socially recognizable meals. The “borrowed forces” that allow the ego to accomplish these regulations come from the superego, the part of the ego that functions as the representative of reality. The superego houses the individual’s understandings of morality and cultural propriety, gleaned first from primary caregivers and then from the world at large. It is the part of the mind that equips the ego with common sense, shame, and a host of other tools that encourage the repression and/or redirection of the drives.

It is important to note that the two topographies are not interchangeable. The id is not synonymous with the unconscious, though a great deal of the id is often unconscious. The ego is not reducible to consciousness, though we are more consciously aware of the ego than we are of the id. If we return to the iceberg metaphor, we might be able to equate the first topography with the oceanic landscape and the second with the iceberg itself. The ocean here would represent the unconscious and the sky would represent consciousness. The lower strata of the iceberg, the vast majority of which is submerged, would represent the id, while the smaller outcropping of ice that floats above water would be the ego/superego complex. The indistinct watermark and the bobbing of the iceberg itself would represent the activity of the drives seeking to be known, as well as the weight of the ego and superego pushing them back.

Psychoanalytic media theorists are primarily interested in the ways that technology and media texts function as objects of these drives, or at least mimic the interplay between the drives and reality that we have discussed thus far. The means by which the components of the interplay form within the individual, however, are still a source of considerable debate among psychoanalysts, one that must be addressed before we can turn our attention to the media. As a result, the next two sections address the two theories of human mental development that have most influenced Psychoanalytic media studies.

Freudian Development

When most people are asked to identify the animating force of Sigmund Freud’s work, they consistently provide the same answer: Sex. This is only partially true, however. Though Freud posited the existence of numerous motivating drives early in his career, he eventually came to believe that human motivation results from two basic drives: the sexual drive and the death drive.6 The sexual drive (also called Eros) compels the individual to connect with others and the world, fueling sexual/reproductive acts as well as lesser drives associated with other physical comforts and the continuation of life. The death drive (also called Thanatos) compels the individual toward division from others and a rejection of the living world, often manifesting as aggression or other destructive impulses. The twin drives are distinct but often inseparable, as even basic acts like eating involve both the destruction and continuation of life.7 Freud believed, however, that the sexual drive is more accessible to speculation than its destructive counterpart, and we often only catch glimpses of the death drive as it operates within or alongside the sexual.8 As a result, sex plays a more prominent role than death in his theories of human development.

Freud’s theory of human mental development begins with the notion that humans are born “polymorphously perverse,” or with the ability to experience sexual pleasure in many different ways. The restriction of sexual pleasure to more common understandings (genital contact, orgasm, etc.) is something that the individual only comes to learn later in life. Early evidence of this diversity can be witnessed in the first of three developmental stages, the oral stage, where the mouth and the act of sucking take on primary significance. Though the ostensible purpose of sucking is nourishment, “the baby’s obstinate persistence in sucking gives evidence at an early age of a need for satisfaction which … strives to obtain pleasure independently of nourishment and for that reason may and should be termed sexual.”9 In other words, while the sucking mechanism allows the infant to eat, it lends itself to other pleasures as well. It may be helpful here to think again on the nature of the drive. While nutrition is certainly a biological need and the act of sucking is instinctual, a variety of objects can come to satisfy this mechanism (including non‐nutritional objects like a pacifier or a thumb), suggesting that there is more to the impulse than purely biological satisfaction.

Progression through the next two developmental stages (anal and phallic) in the first few years of life involves similar experiences of sexual pleasure that result from parts of the body coming into contact with a diversity of objects. In fact, Freud suggests that the particular objects that an individual encounters in these stages (as well as the quality of his or her interaction with these objects) often function as great predictors of the objects that will eventually satisfy the individual’s drives later on in life. One reason that people typically cannot explain why they find a particular object gratifying is because it references or mimics an object they encountered during early development, before they were fully aware of themselves and the world. Freud even suggests it is possible for adults to become arrested in these stages, fixated on objects, areas of the body, or activities heightened during this time (such as consumption, retention, expulsion, etc., as well as objects that lend themselves to these acts).10

A particularly important “object” for the developing child during these stages is the mother. Because the mother is often the provider of many other satisfying objects, Freud suggests that she also becomes an object of sexual satisfaction for the child, an attraction that will lead to incestuous situations later in life if not curtailed. Such denial occurs through the resolution of the Oedipus complex, where the father intervenes and forbids the child from taking the mother as an object of the sexual drive under the threat of “castration.”11 Freud suggests that this threat is embodied in the father’s phallus, which simultaneously signals the father’s sexual power and the child’s powerlessness. The Oedipal prohibition is critical because it serves as a template for all future repression and makes way for the development of the moralizing superego. Successful navigation of the complex, then, sets the child on a path where socially sanctioned forms of sexuality and object choice emerge after puberty, while failure to give up the mother as object at this stage results in a host of consequently troubled or even psychotic mental states. This is why the murderous actions of Norman Bates, the titular character of Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 film Psycho, may be explained above all as a result of his unnatural attachment to his mother.

Freud’s commitment to the sexual nature of human motivation and his framing of gender/family norms from the time period as ahistorical truths have invoked considerable criticism from many academics. Without these questionable decisions, however, his work might never have seen the light of day, and we would not have access to his essential insights regarding the existence of the drives and their role in creating the human subject. One line of thinking that has attempted to shore up some of Freud’s perceived weaknesses belongs to the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, and so it is to his work that we now turn.

Lacanian Development

The first critical difference between Freud’s theories of mental development and those of Jacques Lacan returns us, as always, to the drives. Whereas Freud concentrates on the sexual drive toward union and suggests that we can only understand the death drive in relation to it, Lacan posits the opposite: all drives, including the sexual, are essentially a death drive, in the sense that there is something about all drives that compels the individual beyond permanent connections to any real objects.12 Once a drive achieves its object, it is not satisfied forever. There is always more to eat, as well as the potential for more sexual partners. The various connections with the world that Freud asserts as the basis of the sexual drive are illusory, for that very same drive always compels the individual away from permanent connections with any particular objects.

What is this “something” about the (death) drives that encourages individuals to always move on to new objects? Lacan proposes the conceptual triad of need, demand, and desire as an answer to this question.13 Need is, as it is in Freud, purely biological. Human beings are born with needs for nutrition and comfort that must be met. Demand is a need made symbolic, first put to language by another person (since a newborn cannot speak). Marie‐Hélène Brousse explains it this way:

A baby has a need that is biologically defined and that has an object biologically related to that need. Milk is related to hunger. What happens? As a little human being, it is situated in a linguistic environment. Its mother talks, before it is born and from the moment it is born too. She talks all the time, even when giving the baby the objects its need requires. Her use of the signifier or language has consequences on the feeding of the need. For example, she gives the baby milk at times in a specific way. For need to be satisfied, a little human being has to deal with the Other’s demand. To be satisfied it has to take the Other’s demand into account.14

In opposition to Freud, then, who suggests that the drives are motivators merely present in the id from birth, Lacan interprets the drives as the result of one’s biological needs meeting the symbolic demands that one’s caregiver places on their satisfaction. Put another way, one cannot meaningfully experience motivation until one understands the parameters in which the motivation might occur. It is this emphasis on the power of language and communication in the formation of mental motivations that makes Lacan very popular among media scholars interested in the ways that media symbols and images engage our minds.

Importantly, exposure to the caregiver’s demands also encourages the child to begin making primitive demands of its own, or to use symbols to communicate its otherwise nonsymbolic needs. Crying for food is perhaps the best example of this kind of demand. Whereas a biological need is either filled or unfilled, however, the social nature of the demand adds a critical layer of complication: the request to fill the need can now be denied by the caregiver. Before language, the child merely required milk, whereas the child who asks for milk can be refused. This means that every demand really has two requests: a request for a specific object and a request not to be denied, to be recognized (or loved) by the caregiver. The first is easy to meet as long as the specific object is readily available, but the second is much more difficult. How, Lacan asks, can we ever be sure that the caretaker really loves us? What must the caretaker do to prove this love and fulfill this request? Because these questions can never be answered with absolute certainty, the question of love and recognition remains open. This openness is the genesis of desire, the unquenchable yearning for love or recognition that no one else can ever perfectly or absolutely fill. Desire is the “something” in the drives that keeps them from ever settling on a particular object. Achieving an object is never wholly satisfying because it may satisfy our needs, but it cannot satisfy our desires.

Lacan proposes three “orders” of human experience to help trace the transformation of the individual’s need into desire: the Real, the Imaginary, and the Symbolic. He altered his definition of the Real many times throughout his career, but it is best understood as that part of life that cannot be put into language, or that which cannot be articulated as a demand. The Imaginary is a primary developmental space in which the child learns to make demands; it is the realm of chaotic images and sensory impressions into which the child is born. The child has no sense of self or ego in the Imaginary, but a crucial developmental moment here known as “the mirror stage” begins to organize “the agency known as the ego, prior to its social determination, in a fictional direction.”15 At this point, the child learns to recognize and identify with its own image (most often reflected in a mirror), an immensely pleasurable impression of perfection and wholeness that the child incorporates as the basis of its later ego.

The ego fully materializes as the child acquires the ability to use language and make more coherent demands on others. This acquisition marks its movement from the Imaginary to the Symbolic, or the cultural order of meaning maintained through words and symbols. Lacan suggests that this transition is the culmination of the Oedipus complex, a process that has much more to do with language than Freud initially suggested. The complex unfolds as follows: The primary caregiver, often but not necessarily the mother, stands as a critical figure within the ego‐less perfection of the Imaginary. The “phallus” is the Lacanian term for any object that the child believes the primary caregiver desires within this order.16 Because the child comes to desire recognition from the primary caregiver above all else here through the exchange of demands, he or she reasons that the best way to attract such recognition is to try to become the phallus, or the object of the caregiver’s desire. At this point, a secondary caregiver, often but not necessarily the father, intervenes and denies the child the possibility of this transformation, breaking him or her free of the lure of the primary caregiver’s desire through the introduction of language, law, and social convention (in other words, through the introduction of social reality). Since the “father” denies the child’s ability to become the phallus, Lacan suggests that the child is effectively “castrated.”

Both developmental possibilities at this point come with drawbacks. The child who refuses to give up the quest to become the phallus and forsake the Symbolic order comes to possess an identity marked by some degree of psychosis, for he or she can never formulate an articulable ego or accept fully the limitations of cultural convention transmitted through language. Giving up the quest and accepting language, on the other hand, allows for a coherent ego that the child can present to others through symbols, but it also dooms him or her to living with the insatiable motivation of desire. Lacan refers to the experience of the gap between the Imaginary and the Symbolic that allows for the possibility of desire as lack, and the part of the self lost in the transition between orders (the part that cannot be articulated or spoken about) becomes the unconscious.

For Lacan, then, the idea of identity or consciousness is entirely a fiction, one born out of misrecognition of individual wholeness in the mirror stage and solidified in a system of language where subjects can only ever attempt to represent themselves. His psychoanalysis is clearly very different from its Freudian counterpart in the way it uses language instead of sex to explain the infant’s development and the subsequent mental structures of individuals. Though they conceive of the conscious/unconscious divide quite differently (see Table 7.1), however, both strands of Psychoanalytic theory offer important insights into the ways that unconscious motivations influence human behavior.

Table 7.1 Comparison of Freud’s and Lacan’s theories of human mental development

| Freud | Lacan | |

| Pre‐Oedipal stage | Polymorphous perversity regulated by the pleasure principle | The Imaginary: pre‐linguistic order dominated by images and sensory impressions |

| Sexual pleasure experienced in oral, anal, and phallic stages | Mirror stage: child misrecognizes self as complete and in control; lays basis for eventual ego formation | |

| Post‐Oedipal stage | Identity based on constant curbing of pleasure principle according to reality principle | The Symbolic: linguistic and cultural order where identity arises from attempts to represent self in language |

| Drives brought into accordance with reality and its objects via … | Repression: socially unacceptable desires for objects suppressed from consciousness but retain influence | Desire: drives possess an extra, insatiable quality that results when biological needs become articulated demands |

| Definition of the unconscious | Personal psychical screen that masks repressed desires and attempts to make them known/felt | Aspects of the self that cannot be articulated in language, formed in the transition to the Symbolic |

| The phallus | Actual: the father’s penis, which represents sexual power and masculine presence to the child | Metaphoric: imagined object of the “mother’s” desire in the Imaginary, denied to the child by the “father” |

Now that we have a basic understanding of psychoanalysis, you may be wondering what concepts like drive, repression, and the mirror stage have to do with the media that we consume every day. To better understand the connection, consider the following questions: Why do people continue to attend movie theaters when they can just rent films or watch them via a subscription service at a fraction of the cost? Why do some people watch the same movie over and over again, year after year? Why do we see new movies when we recognize that the vast majority of them rely on the same conventions or plotlines as those we have seen before? Potential answers to these questions can be found in psychoanalysis. Generally speaking, film scholars have historically used Psychoanalytic concepts to explain the structure and appeal of films according to the motivations discussed in the works of Freud and Lacan. They claim that there is something unique about the movie theater venue, the edited shot sequence of film, and the bond between the viewer and filmic narrative that is wholly psychological. They believe that the relationship between drive and reality inherent in each of our lives plays out on movie screens every day, and we watch movies to negotiate this tension. In order to understand how this process takes place, we will now turn our attention to some general assertions of Psychoanalytic media studies and the ways they translate into specific theories.

Psychoanalytic Studies of Media

Scholars in this tradition draw on a number of different theoretical foundations when attempting to understand films and other forms of media, but most agree on a few overriding principles. First, some media texts are structured in such a way that they activate or otherwise tap into unconscious drives. When we watch a movie or gaze at an advertisement, we do so because it allows us to experience the parts of ourselves that are there but not consciously known. In Freudian terms, this means that some media are constructed in such a way as to allow us to indulge in repressed or socially prohibited pleasures. From a Lacanian perspective, this means that the structure of some media allows us to overcome lack and access the Imaginary pleasures which language divides from our conscious mind. Perhaps it is helpful overall to consider such texts as a tool for temporarily undermining the hold of the reality principle and allowing the pleasure principle a bit more reign over our psyche.

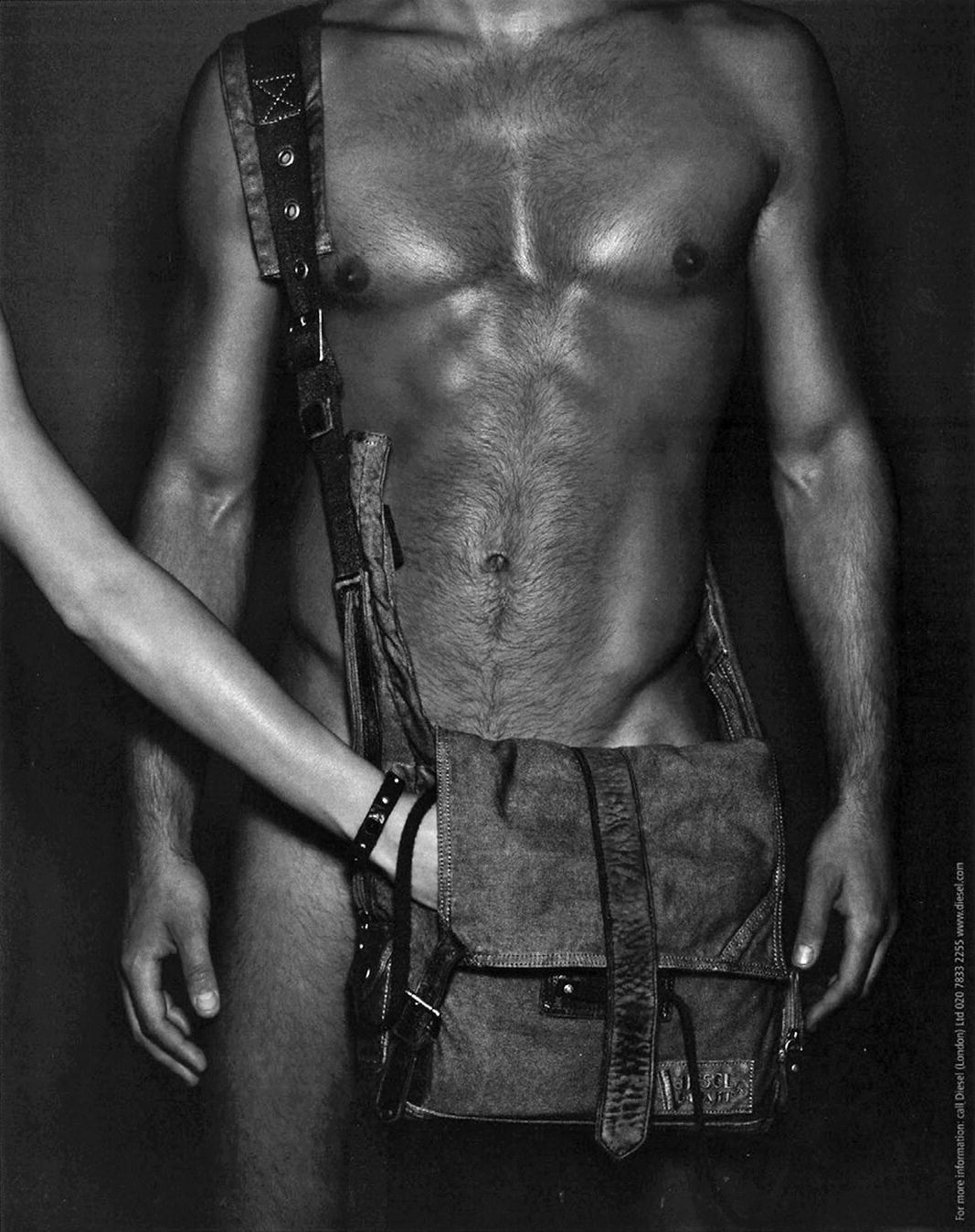

Second, given its basis in sex, many scholars also agree that Psychoanalytic theory is uniquely equipped to explain depictions of gender in American media, especially as they pertain to cultural phallocentrism. Phallocentrism is a social condition where images or representations of the penis carry connotations of power and dominance. Both Freud and Lacan point to the male phallus as an influential symbol in the creation of the human psyche (though Lacan claims it has more of a metaphoric power than does Freud). In both strands of psychoanalysis, the powerful father figure is defined by having command of the phallus, while the rejected mother is defined by her lack of one. For Lacan especially, navigating the Oedipus complex and entering the Symbolic realm of language becomes intertwined with the notion that men are powerful and women are powerless in society, an erroneous understanding prompted by social patriarchy (see Chapter 8). To witness the desirability of the penis in contemporary culture, one need only consider how many tools and structures made to signal awe and power are phallic in shape: swords, rifles, rockets, skyscrapers, obelisks, and more. This logic of desire also occasionally forms the basis of media texts like the Diesel advertisement in Figure 7.1. In essence, within a phallocentric culture, the penis tacitly functions as the object of everyone’s desire. One can see, then, why some feminists like Juliet Mitchell have turned to Psychoanalytic theory in order to address how the social systems we encounter at an early age infuse our developing minds with constructed notions of gendered power and inequality.17

The following sections consider three historical developments in Psychoanalytic film studies: apparatus theory, the male gaze, and fantasy. This list is not exhaustive of the field, but it is appropriate for an introductory chapter. When possible, we extend these insights to the medium of advertising to expand the utility of these ideas. After establishing this baseline, the chapter will conclude with a brief discussion regarding other significant developments within Psychoanalytic media studies.

Figure 7.1 Diesel advertisement.

Source: Courtesy of The Advertising Archives.

Apparatus theory

First proposed by scholar Jean‐Louis Baudry, apparatus theory is the earliest Psychoanalytic approach to film. This approach claims that the actual environment and machinery of the cinema activates a number of Psychoanalytic motivations within viewers. In his analysis of Plato’s famous cave allegory, Baudry points out that “the text of the cave may well express a desire inherent to a participatory effect deliberately produced, sought for, and expressed by cinema.”18 In other words, the same unconscious drives that fueled Plato’s writings may have also inspired the creation of the modern movie theater and the genesis of film itself. Here, Baudry is suggesting that all human beings throughout time have experienced the repression of drives or their transformation into desire as a result of psychical development, and film is simply the contemporary means by which we negotiate these mechanisms.

The mechanics of cinema allow for this negotiation in a number of ways. According to Baudry, the actual context of viewing a movie in a theater “reconstructs the situation necessary to the release of the ‘mirror stage’ discovered by Lacan.”19 The theatrical environment, in other words, plays upon the process of image identification first enacted in the Lacanian mirror stage. Lacan points out that the child approaching his or her mirror image lacks significant motor control and relies mostly on vision to understand the world. The mirror stage is pleasant and confirming for the child precisely because it displays a false sense of wholeness and control to make up for this lack. Baudry explains that the conventions of the theater (giant images on the screen and a passive, seated audience) also create a sense of visual dominance and restricted movement, causing viewers to again unconsciously rejoice in mirror‐stage feelings of wholeness, mastery, and control while watching a film.

For Baudry, then, the narrative or content of the film is not as appealing as the actual process of viewing, because “the spectator identifies less with what it represented, the spectacle itself, than what stages the spectacle, makes it seen, obliging him [sic] to see what it sees.”20 He also draws connections between the movie theater and the womb, claiming that the context of watching a movie in a theater causes viewers to unconsciously regress back to the Imaginary and pleasurable experience of a connection to the primary caregiver. This assertion may seem odd until we consider the manner in which theater audiences actually watch films. The darkness of the theater and the relative immobility of the audience both suggest aspects that break us from our daily routine and recall womb‐like qualities.

Christian Metz, another scholar interested in the Psychoanalytic aspects of film, agrees with Baudry’s basic understanding of the cinematic apparatus and extends it in important ways. Metz recognizes that identification is an important component of the apparatus, but he claims that it also taps into the Freudian drives of voyeurism and fetishism. The conceptual trio of identification, voyeurism, and fetishism provides a foundation for a great deal of the Psychoanalytic work that was to follow, and it is important to understand how each of these notions informs the viewer/film relationship.

Like Baudry, Metz asserts that identification with the screen occurs through a re‐enactment of the confirming mirror stage for viewers, but he points out that it can never actually function as a mirror. Because the film can never reflect back the actual image of the viewer, the relationship between the viewer and the screen/mirror is primarily one of identification with the actual ability to perceive first encountered in the mirror stage. In his book, The Imaginary Signifier: Psychoanalysis and the Cinema, Metz characterizes the viewer’s mental process in this way:

I know that I am perceiving something imaginary … and I know that it is I who am perceiving it. This second knowledge divides in turn: I know that I am really perceiving, that my sense organs are physically affected, that I am not phantasizing, that the fourth wall of the auditorium (the screen) is really different from the other three … In other words, the spectator identifies with himself [sic], with himself as a pure act of perception (as wakefulness, as alertness).21

In this way, instead of merely regressing back to the context of the mirror stage as Baudry claims, viewers experience the mirror stage’s process of perception by establishing a primary identification with the camera’s field of vision as it captures the events in the film. This in turn leads to a secondary identification with the looks of characters in the film, whose points of view are captured through shooting and editing techniques. In essence, Metz claims that viewers know that they are not seeing themselves in the screen/mirror, but they do resonate with the actual mirror‐stage processes of perceiving and identifying with images outside of themselves by aligning themselves with the scope of the camera and the looks of the characters.

After establishing these primary and secondary identifications with the apparatus, Metz claims that viewers participate in what he calls “the passion for perceiving,” or scopohilia. Scopophilia refers to pleasure that comes from the process of looking, and Freud identifies it as one manifestation of the sexual drive. Should the aim of a drive deviate from actually acquiring its object, “visual impressions remain the most frequent pathway along which libidinal excitation is aroused.”22 For Metz, derivatives of scopophilia like voyeurism and fetishism help explain the draw of the movie theater and the fascination with film.

Voyeurism, or the process of experiencing pleasure by watching a desired object or person from a distance, is a powerful concept at work in the movie theater. Maintaining a distance between looker and object is key to the pleasure of voyeurism, and Metz sees this distinction as a result of the very nature of desire and lack. Remember that, according to Lacan, one’s desires can never be fully satisfied because they are founded on a fundamental uncertainty. Achieving an object of a drive never quite satisfies us because we soon discover that the object cannot fulfill every yearning. Put another way, our desire for an object is stronger when we are at a distance, before we achieve the object and discover its shortcomings. Metz recognizes that many arts rely upon activating the voyeuristic tendencies inherent in viewers, but film is an especially potent realm of this type of scopophilic pleasure. Like the theatrical performance of plays, cinema screenings place viewers at a distance from the object watched. Unlike live drama, however, the objects are not actually present in the movie theater. There is no true exhibitionist complement to the cinematic voyeur, no actual object or person to be watched beyond the flat, projected image. This absence increases the perception of distance and lack between voyeur and object, increasing the possibility of scopophilic pleasure.

Fetishism, or the psychic structuring of an object or person as a source of sexual pleasure, is another Freudian concept bound to the notion of looking that helps explain the draw of the cinematic apparatus. For Freud, fetishizing is an important part of navigating the Oedipus complex that helps explain the otherwise inexplicable attraction in later life to objects that many would deem “nonsexual.” In the complex, the child comes to understand for the first time that a power differential exists between the mother and the father on the basis of who possesses the phallus. The child thus has two contradictory thoughts: (1) all caretakers are powerful and (2) some caretakers are more powerful than others. In paraphrasing Freud, Metz claims that the child will “retain its former belief beneath the new one, but it will also hold to its new perceptual observation while disavowing it on another level.”23 The knowledge that some can lack the powerful phallus terrifies the child and forces him or her to imagine the implications of his or her own loss or lack. This “castration” anxiety is so great that the child will sometimes fixate on a nearby object in the physical environment, transforming it into a fetish that denies the potential absence of the phallus and becomes a source of pleasure in itself. The fetish effectively “puts a ‘fullness’ in place of a lack, but in doing so it also affirms that lack. It resumes within itself the structure of disavowal and multiple belief.”24

Metz sees fetishism operating in the cinematic apparatus through a disavowal inherent to the watching process. On one hand, viewers understand that the objects, characters, and events unfolding in the film before them are not real. On the other, quality films will attempt to mimic real life as much as possible and instill within viewers a sense of realism. Viewers, wrestling with the tension between consciously disavowing the film’s truth and unconsciously believing the story as true, turn their attention to a fetish to relieve this discomfort. For Metz, the diversionary cinematic fetish is the machinery of the film itself: the director’s techniques that help frame and progress the film. “The cinema fetishist,” Metz writes, “is the person who is enchanted at what the machine is capable of.”25 Thus, the apparatus is the site where viewers relive Oedipal conflict and anxiety, and they negotiate these negative feelings again through the process of fetishism.

Apparatus theory (and especially the work of Metz) provides an important foundation for the field of Psychoanalytic media studies, but one would be hard pressed to find a scholar today who wholly supports this viewpoint. In many ways, apparatus theory is considered a historical moment rather than a vibrant area of contemporary research. Critics of the theory claim that it is a naïve approach to film that ignores a number of cinematic qualities (sound, historical context, etc.), and Feminists often critique the approach for its relative silence toward issues of inequality and representation in film narrative. In fact, this critique represents the next significant application of Psychoanalytic theory in film scholarship, a body of work centered on how psychoanalysis influences the depiction and reception of gender in film.

The male gaze

With the publication of Laura Mulvey’s landmark piece, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” in 1975, some Psychoanalytic media scholars began shifting their attention away from the context of the cinema to focus more on the actual form and narrative of the films involved. This shift opened up a field of study on what has become known as the male gaze. In her article, Mulvey contends that not only is the film viewer called upon to participate in unconscious desire via the apparatus theories of Baudry and Metz, but the cinema itself uses psychoanalytic concepts of desire, identification, voyeurism, and fetishism to frame its narratives across gendered, ideological lines.26 It is no accident that the protagonists of most film narratives are male, and Mulvey asserts that Metz’s matrix of identification and scopophilia actually operates within a powerful phallocentric frame of reference.

Remember that within a phallocentric frame, men are defined by the presence of the powerful phallus, and masculinity and male sexuality are defined by favorable concepts of action and primacy. Women are defined by an absence of the phallus, and therefore femininity and female sexuality are associated with passiveness and powerlessness. In considering this perspective, Mulvey writes:

There is an obvious interest in this analysis for feminists … It gets us nearer to the roots of our oppression, it brings an articulation of the problem closer, it faces us with the ultimate challenge: how to fight the unconscious structured like a language (formed critically at the moment of arrival of language) while still caught within the language of the patriarchy. There is no way in which we can produce an alternative out of the blue, but we can begin to make a break by examining patriarchy with the tools it provides, of which psychoanalysis is not the only but an important one.27

Accordingly, Mulvey turns to psychoanalysis to propose a theory of the cinema that associates desire and looking with gendered power. She melds concepts of identification and scopophilia with the male‐presence and female‐absence thesis of phallocentrism to arrive at a structure for filmic narrative: male/subject/looker and female/object/looked at. Within classic film narrative, Mulvey claims that male characters are active subjects who look upon female characters as passive objects. Likewise, the look of the camera, the way that the shot decisions of the director frame the narrative, is also inherently male and places the female body on display for audiences. Taken together, these two concepts form Mulvey’s notion of the male gaze. In accessing a film through this male gaze, viewers experience unconscious, scopophilic pleasure in two ways: (1) by identifying with the male gaze of the camera as it concentrates on female characters and (2) by identifying with the male characters who gaze at female characters within the film itself.

In order to understand how Mulvey’s thesis builds upon Metz’s insights, as well as how her ideas may find continued application in media beyond film today, consider the Nikon advertisement in Figure 7.2. We would suggest that part of the appeal of this ad arises from Metz’s understanding of voyeurism. Though it directly references the popular image of the “Peeping Tom,” the extremely large camera screen framing the models on the bed effectively creates one more voyeur here: the consumer of the ad. In the same way that a film screen mediates between the viewer and the projected object in Metz’s work, the Nikon camera screen establishes an illusory barrier between the models in the ad and anyone who encounters it. In both cases, the screens draw attention to the impossible distance between the viewer and the mediated object, mirroring the experience of lack at the core of Psychoanalytic desire. At the same time, Mulvey would consider it no accident that the gazed‐upon objects in the ad are women, while the implied voyeurs here are men (or Peeping Toms). Like many deployments of gazing in mainstream media, the ad frames the ability to look as masculine and the ability to draw the look as feminine, which intensifies its scopophilic potential. In the process of gazing at the image, consumers are encouraged to identify with the look of the camera or the look of the implied voyeurs within the scene itself. All of these positions, however, are masculine in nature.

Figure 7.2 Nikon S60 advertisement.

Source: Courtesy of The Advertising Archives.

Mulvey was primarily concerned with analyzing the narratives of classical Hollywood cinema, but one can still find the male gaze operating in contemporary films as well. The 2014 science fiction film Ex Machina provides a striking example. The film concerns a young computer coder named Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson) who is invited to spend a week at the estate of his employer, a reclusive genius named Nathan (Oscar Isaac). When Caleb arrives at the estate, he discovers that Nathan has constructed a remarkably lifelike, overtly feminine robot named Ava (Alicia Vikander). Nathan soon convinces Caleb to act as the human participant in a lengthy Turing test to gauge the quality of Ava’s artificial intelligence, and the coder’s subsequent interactions with the robot include a number of elements conspicuously in line with Mulvey’s ideas regarding the male gaze.28

Nathan confines Ava to living quarters largely made of transparent walls, which afford Caleb relatively unobstructed views of her behaviors during their conversational sessions. In addition, Caleb also discovers that Nathan has wired the estate in such a way that he can watch Ava at any time from the television in his guest room. Together, these factors invite Caleb to gaze intensely upon Ava’s beautiful body, very often while he is alone and with increasing frequency as the film progresses. Much of Ava’s body is also made of translucent plastic, which permits Caleb’s gaze (as well as the audience’s own) to penetrate into her internal circuitry. This merging of Caleb’s gaze with the audience’s personal spectatorship of Ava is especially apparent during the duo’s third interactive session. In this meeting, Ava confides to Caleb that she wants to do something special before slipping away to one of the few parts of her enclosure that he cannot see. As Caleb strains unsuccessfully to get a glimpse at what Ava is doing, the camera cuts to her outside of a small dressing area, caressing a simple dress and wig. The camera then cuts back and forth between shots of Caleb struggling to see Ava and the robot slowly dressing herself; it even lingers on her at one point as she slowly rolls a stocking up her leg. Such editing strongly positions the film’s viewers as surrogates for Caleb, taking up the visual objectification of Ava when he can no longer do it himself.

The interpretive power of the male gaze in film does not end with looking relations. Mulvey asserts that all female objects will eventually create anxiety for viewers/subjects because their very existence as woman references the absent phallus, Oedipal “castration,” and social shortcoming. In order to contain the threat of castration they represent, Mulvey claims that female characters in film are neutralized through various narrative developments of voyeurism and fetishism. Voyeuristic mechanisms in a film, for example, often invite viewers to experience a “preoccupation with the re‐enactment of the original trauma (investigating the woman, demystifying her mystery)” even as the film’s narrative typically features a “devaluation, punishment or saving of the guilty object.”29 In other words, many films associate acts of looking with depictions of sadism or feminine frailty because the link creates the illusion of control over (and punishment of) the offending female object. Narrative developments based in fetishism, conversely, disavow castration anxiety by transforming the female object into a source of sexual beauty and pleasure. This is most often achieved by diverting attention away from the complexity of the female character and toward specific parts of her body.

Sometimes, the female character experiences both punishment and simplification, as is the case with Ava in Ex Machina. Near the end of the film, Caleb becomes so obsessed with Ava that he overrides the estate’s security measures and allows her to escape. As she navigates the complex, Nathan confronts her and shatters her arm when she attempts to resist recapture (though he is the one killed in their resulting scuffle). Ava then discovers the bodies of multiple discarded robots in Nathan’s bedroom, and she harvests these older models for a new arm and for synthetic skin to cover her transparent appendages. Though in some ways the next scene of Ava contemplating her naked, whole, and apparently human body in a mirror is empowering, in others it underscores her existence only as an assembly of beautiful parts that have experienced terrible traumas.

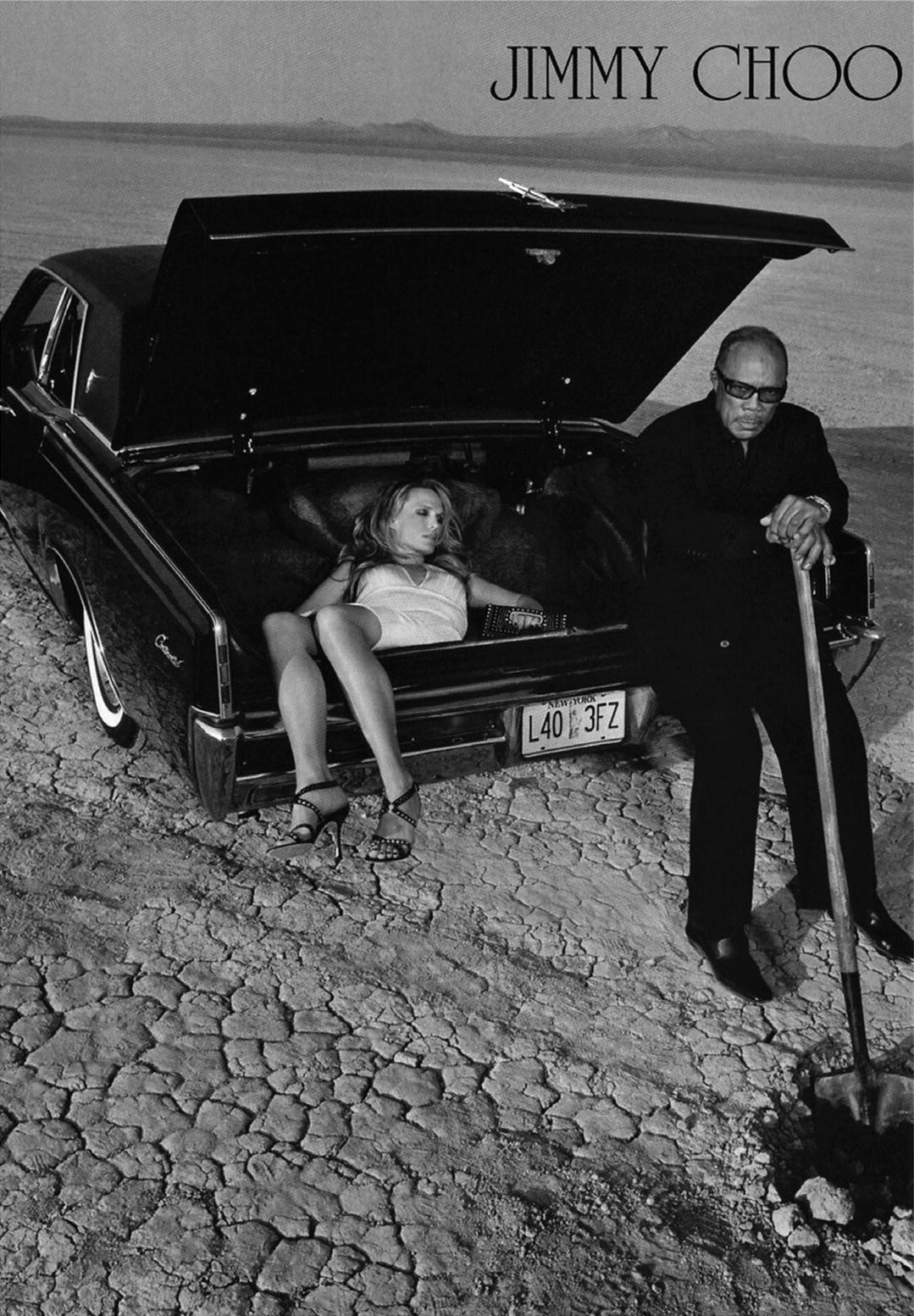

Because practices of looking and voyeurism are not confined to the cinema, however, it is possible to discover the sadistic punishment and fetishistic reduction of women in other forms of media as well. The advertisements in Figures 7.3 and 7.4 illustrate this tendency. While heaving a woman’s incapacitated body into an automobile trunk may seem like a convoluted way to display and advertise Jimmy Choo shoes, the depiction of this act makes a bit more sense within the Psychoanalytic register of the male gaze. The ad invokes scopophilic pleasures organized around a female object while simultaneously punishing her weakness and relieving any unconscious anxieties that she may summon in the audience. Compared to this dire desert, the posh bedroom in the Dolce & Gabbana ad may seem like a far less dangerous location to advertise designer clothing, but we would suggest that this image quashes viewer anxieties by performing a different sort of violence on the female object, namely a “decapitation” that reduces her fetishistically to a pair of legs.

Figure 7.3 Jimmy Choo advertisement.

Source: Courtesy of The Advertising Archives.

Before moving any further, it is important to pause and note an important distinction. The fact that the gaze of the camera in contemporary society is often inherently male (and heterosexual, for that matter) does not preclude other social groups from gaining scopophilic pleasure from gazing. It would be ridiculous to say that only men gain pleasure from watching movies or looking at advertisements. The sheer popularity of these institutions in America speaks against the idea. Instead, research on the gaze points to the ways that film and other forms of media can tap into mental structures and orient us to receiving unconscious pleasure across gendered, ideological lines. All viewers can experience the pleasure of looking in the media, but texts often ask them to do so by identifying with a masculine perspective (as Mulvey later asserted in a 1981 article30). For Mulvey, that process of identification supports systems of social inequity and decreases the possibility of viewing positions based in the experiences of subjugated groups finding a place in mainstream media.

Despite the interpretive utility and political importance of the male gaze, a nagging question remains: Is it outdated? Mainstream media representations of gender have certainly become more complex since the publication of Mulvey’s thesis in 1975. How, for example, might Mulvey account for the existence of something like Steven Soderbergh’s 2012 film Magic Mike, which follows the lives of a group of male strippers living in Florida? In this mainstream film and others, the male body is framed as a sexual object with the same visual codes that she reserves for the female body, suggesting that her thesis may no longer apply. Many scholars note, however, that films and other forms of media that appear to objectify the male body also regularly feature codes that simultaneously negate such objectification. In his analysis of the male pin‐up in popular magazines, for example, Richard Dyer claims that erotic images of men always contain “instabilities.”31 Though objectified, the male model often denies the look of the viewer by looking away from the camera or positioning his body in ways to connote ideas of power and independence. Male objects tend to be portrayed as more active than their female counterparts, and the “natural” link between muscles and the male object also works to break the image free of passive connotations. While instances of male objectification do occur, then, they carry connotations of power and activity that are typically absent in representations of female objects.

Figure 7.4 Dolce & Gabbana advertisement.

Source: Courtesy of The Advertising Archives.

This disavowal of the male as object manifests in other ways as well. Steve Neale notes that though the male body does work as a spectacle in older films like Spartacus (1960) and Ben Hur (1959), those images come to audiences primarily through the looks of other characters who fear or hate the objectified characters (thereby dampening the possibility of erotic desire).32 Male bodies that do carry an air of erotic appeal are also often feminized, such as the body of Rock Hudson in the melodramas of Douglas Sirk. Kenneth MacKinnon suggests that these codes are so instantiated that audiences regularly assume a male object to be a source of pleasure for some other social group than themselves.33 To illustrate this point, MacKinnon notes the reaction of his students in a film seminar to a music video that prominently objectified and sexualized the male body:

An older woman thought that it was surely meant for teenaged girls; a younger woman was sure that it was meant for gay males; and a remarkably “out” male who should, by the latter’s logic, have recognized his centrality in the audience for those videos claimed with certainty that they were not for “the likes of” him.34

From this example, MacKinnon concludes that the male object often has only fictitious or assumed viewers, which certainly diminishes its status as an object.

As a result, rather than contradict Mulvey’s theory of the male gaze, many scholarly discussions of the male object tend to reinforce her thesis that “the male figure cannot bear the burden of sexual objectification.”35 The treatments of many images of the male body tacitly fortify the widespread logic of the male gaze by denying men any significant object status. At the same time, there is more to media than just the framing of objects, and some scholars have theorized the existence of female and queer gazes on the basis of narrative, aesthetic, and other media conventions.36 These theorists assert that Mulvey’s distinction between male subject and female object is not nearly as clear or explanatory as it may originally appear, and the process of identification with the media is actually far more complicated than she claims. One of the most prominent areas of study that reflects this destabilization of the subject/object relationship is fantasy theory.

Fantasy theory

In her 1984 article “Fantasia,” Elizabeth Cowie draws upon the work of Freudian scholars Jean Laplanche and Jean‐Bertrand Pontalis to explain how Psychoanalytic theory may allow for more fluid or mobile processes of identification in films than Mulvey proposes.37 A fantasy is a mental representation of conscious or unconscious wish fulfillment, and (following Freud) Laplanche and Pontalis see it as a primary aspect of mental development. Fantasy is born in the moment that the suckling child begins to gain sexual satisfaction from feeding. The child wishes for and fantasizes about being with the object (typically the mother’s breast, or a bottle) when it is absent. From this understanding, we can assume two qualities of fantasy. First, wishing creates fantasy, and we fantasize only because we wish for objects of the drive. Second, fantasy is a scene of the drive. It is not the drive in itself, but rather a mental structure that contains the drive and stages the achievement of its object.

Fantasy also, importantly, allows us to assume multiple perspectives. For Freud and Laplanche, this ability to identify with multiple perspectives in fantasy comes from the primal or first fantasy: a fantasy about the sexual union of the mother and father that created us.38 Conscious or unconscious fantasies about this moment involve multiple parties, and in considering the perspectives of those parties, we establish a template for all future fantasies. Put another way, a child might fantasize about watching the father and mother engaging in the sexual union that created him or her, and within the fantasy that child might identify with the father, the mother, his or her own watching self, another person watching, or various other perspectives. In this light, we can see that fantasy is just as fundamental as the pleasure principle and other mechanisms of early mental development. Just as many of our drives remain beyond our conscious recognition, however, much of the fantasy we experience as individuals also manifests unconsciously.

It is this type of unconscious fantasy that primarily informs the work of media scholars in this tradition. They claim that films engage us like a fantasy that happens to be outside of our heads, inviting us to identify unconsciously with multiple parties in the narrative in order to work through and satisfy our drives. Because we can identify with multiple perspectives in a filmic/fantasy scene, these scholars question Mulvey’s notion that audiences gain pleasure only from identifying with the watching male subject on screen. Instead, a film operates as a phantasmic space where viewers can identify with the camera’s gaze, same‐sex characters, opposite‐sex characters, objects, and virtually any other aspect of the narrative. Pleasure comes not from visually consuming the female objects in the film through the male gaze, as Mulvey claims, but rather from identifying with characters involved in achieving the objects of their drive on screen. Instead of identifying solely with the male protagonist as he searches for an object in the narrative, audiences in fantasy are free to identify with any aspect of the quest (or with multiple aspects at different times during the film).

Much like Metz’s earlier claims about voyeurism in film, Cowie asserts that pleasure in the filmic fantasy comes from the endless deferment of Lacanian desire within the narrative. Recall that desire is predicated on the person being removed from the desired object; it is motivating only until the person achieves that object. As such, viewers identifying with characters in the film‐as‐fantasy gain pleasure in the narrative moments that defer and prolong desire, not in the moments where characters actually achieve the objects of their desires. As Cowie puts it, though narratives almost always come to closure by the end,

inevitably the story will fall prey to diverse diversions, delays, obstacles and other means of postponing the ending. For though we all want the couple to be united, and the obstacles heroically overcome, we don’t want the story to end … The pleasure is in how to bring about the consummation, is in the happening and continuing to happen; is how it will come about, and not in the moment of having happened.39

In this tradition, then, we engage with films because they represent public fantasies that allow us to work through unconscious drives and wishes. We identify with a range of subject positions within the overarching narrative of a film, a narrative that often represents the quest for a desired object. Pleasure in watching, however, comes from the moments in the film when the quest is prolonged or stunted, such as the introduction of the antagonist or other obstacles that keep the protagonist from reaching his or her goal.

The 2016 musical La La Land provides an excellent basis for thinking about film as unconscious fantasy. The story follows an aspiring actress named Mia (Emma Stone) and an idealistic jazz musician named Sebastian (Ryan Gosling) as they attempt to balance their achievement of stardom in Los Angeles against a turbulent love affair. While slickly modern in some of its elements, the film nevertheless relies on many traditional musical conventions: characters randomly break into song and dance, costumes invoke nostalgia for a bygone era, and (in one particularly memorable scene) Mia and Sebastian slow dance together while floating above the seats of a planetarium. We would suggest that these very evident breaks with everyday reality do much to invite contemporary viewers to understand the film as “fantastic.” At the same time, neither character is more clearly the protagonist of the narrative than the other, which encourages audience members to identify with either Mia or Sebastian at various points in the film.

The difficulty of wholly satisfying one’s desires represents the central tension of the story. At the beginning of the film, Mia and Sebastian bond over the fact that they both feel artistically stifled. Mia goes on constant and often humiliating auditions without ever receiving a callback, and Sebastian plays show tunes for uninterested patrons at a local restaurant. This mutual failure quickly becomes the basis of a budding romance, but as the film progresses and the characters finally begin to achieve a measure of success in their respective fields, it becomes harder for them to maintain a meaningful connection to one another. The message here seems to be that one must choose between romantic and professional desires; the attainment of one often defers the possibility of the other. This point is particularly apparent in the conclusion of the film, when the now famous Mia stumbles by chance into Sebastian’s well‐regarded jazz club and imagines what their life would have been like had they remained a loving couple. The vision appears as a musical montage unfolding in Mia’s mind, and with it audience members must contend at once with the fruits of the duo’s professional accomplishments and a heart‐wrenching image of their endlessly deferred romantic desires. In this way, the film provides many opportunities for viewers to glean pleasure from the postponement of the characters’ satisfactions, and the ending allows them to dwell at length on the fulfillments foreclosed by their pursuits.

Fantasy theory’s basis in narrative and the fluid process of identification represents an attempt to compensate for the perceived limitations of apparatus theory and ideas regarding the male gaze. Still, Teresa de Lauretis fairly criticizes this approach for overlooking some key discrepancies in Psychoanalytic fantasy:

[F]irst, a particular fantasy scenario, regardless of its artistic, formal, or aesthetic excellence as filmic representation, is not automatically accessible to every spectator; a film may work as fantasy for some spectators, but not for others. Second, and conversely, the spectator’s own sociopolitical location and psycho‐sexual configuration have much to do with whether or not the film can work for her as a scenario of desire, and as what Freud would call a “visualization” of the subject herself as subject of the fantasy: that is to say, whether the film can engage her spectatorial desire or, literally, whether she can see herself in it.40

De Lauretis acknowledges, in other words, that we all fantasize, but she reminds us that the contents of those fantasies are unique to ourselves. Consequently, there is no reason to believe that the specific narrative content of a particular film appeals uniformly to everyone.

Fantasy theory was one of the last concerted gestures within Psychoanalytic film studies, which has somewhat fallen out of vogue since the 1980s. Contrary to those who suggest that other approaches to the media have completely eclipsed psychoanalysis, however, some media scholars continue to use Psychoanalytic concepts in order to investigate particular texts and technologies for the ways they might resonate with mental forces. These developments represent the best chance for another movement within Psychoanalytic media studies like those we have outlined in this chapter, so we conclude our exploration with them.

Contemporary Scholarship in Psychoanalytic Analysis

While psychoanalysis remains a viable means for explaining the appeal of media texts today, some scholars have largely moved away from the comprehensive perspectives of apparatus theory, the male gaze, and fantasy in favor of more localized or case‐specific approaches. These scholars acknowledge that Psychoanalytic theories may no longer have widespread conceptual purchase, but they also argue that Freudian and Lacanian insights are sometimes the most useful tools for understanding the narrative or structural elements of a given text. In essence, given their particular qualities, some texts simply beg to be “psychoanalyzed.”

David Rudd’s analysis of Neil Gaiman’s Coraline is a good example of this trend.41 The novel revolves around the fantastic adventures of Coraline, a young girl who attempts to leave her inattentive parents by escaping into a mirror universe where everything is the opposite of her own. Though initially charmed by the extreme attention and praise she receives from her new, doting parents, Coraline comes to realize that her “other mother” also plans to trap her in the bizarre universe forever. The woman is, in effect, (s)mothering Coraline to death. Rudd reads Coraline in part as an allegory for the Lacanian developmental trajectory of need, demand, and desire. As a product of language, desire fuels our constant yearning for love and recognition from the (m)other, but fulfillment of this yearning is constitutively impossible unless we somehow forsake the social/Symbolic realm of language for the specular confusions of the Imaginary (in short, psychosis). The mirror world and the fulfilling “other mother” in Coraline are dangerous precisely because they embody

all that we need to set aside in order to live, but which will continue to shadow us, and which, indeed, can at times seem appealing. In pursuing her wish to be special, then, Coraline comes too close to realizing her desires. After this realization, Coraline spends the rest of the book trying to re‐establish a distance, to rebuild the fantasmatic screen that allows her to function in the world.42

Coraline and its filmic adaptation may be intended for young adults, but Rudd suggests that its underlying Psychoanalytic structure should resonate with all audiences who experience the temptations and dangers of desire.

Some scholars take this interpretive logic a step further when they suggest that media texts that appear to be particularly open to Psychoanalytic readings may also be viewed as reflections or “symptoms” of deeper cultural developments and anxieties. Much as Freud and his contemporaries used knowledge of the drives and the Oedipus complex to probe the depths of patients’ psyches and discover the roots of their neuroses, some media scholars utilize Psychoanalytic concepts to “diagnose” cultural and historical moments through the mental structures or processes presented in media of the time. Psychoanalytic understandings of paternal influence, for example, allow Joshua Gunn to link the “father trouble” at the heart of the films Fight Club (1999) and War of the Worlds (2005) to larger cultural issues of personal identity and power at the beginning of the 21st century.43 In the first instance, Gunn and Thomas Frentz argue that relations between the three primary characters in Fight Club are fundamentally Oedipal. The film’s extreme violence may be read as a representation of the psychoses that result when the paternal figure fails to intervene in the mother–child dyad. Interestingly, this cinematic violence strongly mirrored (and occasionally inspired) increasing amounts of actual violence at the time of the film’s release, leading the authors to conclude that Fight Club may in fact index a modern yearning for order that can combat a diffuse cultural “psychosis,” or a pervasive inability to reconcile personal identity with social reality. Gunn makes a somewhat resonant argument in his essay on War of the Worlds. Here, the actions of main character Ray Ferrier (Tom Cruise), a father trying to protect his family during an alien invasion, are akin to the prohibitionary and structuring responsibilities of the paternal figure within the Lacanian Oedipal moment. While Worlds activates viewers’ need for security in the same way that Fight Club dramatizes yearnings for accountability, Gunn is troubled by the way that director Steven Spielberg yolks the unconscious paternal function to very specific political events at the time of its release, most notably the terrorist attacks of 9/11 and the Bush Administration’s bid for global power. Ultimately, Worlds stages a disaster so that its viewers come to wish for a “father” who can protect them outside of the theater as well. As Gunn summarizes it, “War of the Worlds unwittingly teaches spectators how to love a dictator,” in part by tapping into the deepest layers of the unconscious.44

Such symptomatic readings of culture are, of course, possible beyond the medium of film as well. In Television and Youth Culture: Televised Paranoia, Jan Jagodzinski argues that the sudden appearance of paranoid and/or “parentless” teenagers on television programs like Roswell and Dawson’s Creek since the late 1990s indicates a much more fundamental, “post‐Oedipal” shift within American life.45 Eternal youth, he notes, is currently an ideal to which many people aspire. Infants are encouraged to grow into their youth more quickly, and adults are pressured to hold on to it for longer. If everyone is a youth, however, then there is no Oedipal authority to hold people accountable to social reality, resulting in what Jagodzinski calls a widespread “orphan” subjectivity rife with paranoia. Thus, the now common image of the televised teenager who does not attend classes regularly, who secretly battles a variety of supernatural forces, or who only occasionally checks in with largely absent/clueless parents is not an entirely random trend. Instead, Jagodzinski suggests, these paranoid and defensive teens reflect deeper unconscious issues that accompany a contemporary cult(ure) of youth.

Though the interpretive and symptomatic approaches to texts are both well represented in contemporary Psychoanalytic media studies, a smaller group of scholars utilize Freudian and Lacanian ideas to understand the appeal of certain technologies independent of specific content. Perhaps the best application of psychoanalysis in this approach is in relation to the internet. In a sustained project across a number of different publications, for example, Jodi Dean argues that part of the popularity of web technology stems from its ability to host the compulsive nature of the drive.46 Lacan suggests that the drive would prefer to circulate endlessly around its object rather than ever actually reach it, a logic that Dean sees replicated in hyperlinking, Facebook “liking,” blog posting, and other activities that come to construct a circuit of constant and interminable activity online. This resonance between mind and machine is not accidental. Dean suggests that these new technologies and platforms signal the historical rise of “communicative capitalism,” where a small cadre of tech wizards and corporations benefit financially from the unconscious capture of a population lulled into political complacency. In short, what seems like genuine participation in the public sphere of the internet is nothing more than the chaos of endless chatter, inspiring little to no action. Dean ultimately suggests that people (and, specifically, the political Left) need to overcome the seductive pull of new media technologies if genuine political change is ever to be possible.

However, Slavoj Žižek, arguably the most popular Psychoanalytic media scholar of our age, disagrees somewhat with Dean’s thesis.47 Žižek also sees a strong resonance between Psychoanalytic mechanisms and the web, but he is less ready to assume that the technology automatically and unconsciously captures its users. Instead, after outlining four popular theses regarding the Psychoanalytic implications of the internet (which are somewhat beyond the scope of our introductory chapter), Žižek concludes by recognizing that there is more to the relation than just the technology–user interface:

What if it is wrong and misleading to ask which of the four versions of the libidinal or symbolic economy of cyberspace that we outlined (the psychotic suspension of Oedipus, the continuation of Oedipus with other means, the perverse staging of the law, and traversing the fantasy) is the “correct” one? What if these four versions are the four possibilities opened up by the cyberspace technology, so that, ultimately, the choice is ours? How will cyberspace affect us is not directly inscribed into its technological properties; it rather hinges on the network of sociosymbolic relations (e.g. of power and domination) which always and already overdetermine the way cyberspace affects us.48

Žižek thus underscores Dean’s careful attention to the economic relations of the current era while also reminding us that internet technology should not be automatically forsaken for its Psychoanalytic properties.

Conclusion

This chapter has looked at how the Psychoanalytic concept of drive helps explain the structure of media technologies and texts, with film as the historically predominant area of analysis. Psychoanalytic theorists Sigmund Freud and Jacques Lacan provide a somewhat overlapping understanding of the formative process that results in an individual’s psychical structure, and their respective theories of repression and desire each help shed light on why films and other forms of media appeal to audiences based on this mental formation. The three approaches to film outlined in this chapter (apparatus theory, theories of the male gaze, and fantasy theory) all attempt to explain how the early structuring of the human mind results in the particular management of film in society: filmic evolution, screenings, shot sequences, characterization, narratives, and so on. Contemporary scholars have extended these approaches by questioning their assumptions about the nature of gender, sexuality, and desire, resulting in a small but vibrant field of Psychoanalytic research today. Though Psychoanalytic approaches to media texts are not as popular as they were in the 1970s and ‘80s, Psychoanalytic scholars continue to present the field of media studies with a fascinating synthesis of psychology with books, film, television, and the internet. If nothing else, psychoanalysis provides us with a multifaceted interpretation of the psyche, an important perspective on contemporary media, and a language to articulate the at times inexplicable attraction we feel toward popular texts.

SUGGESTED READING

- Albano, L. Cinema and Psychoanalysis: Across the Dispositifs. American Imago 2013, 70, 191–224.

- Bateman, A. and Holmes, J. Introduction to Psychoanalysis: Contemporary Theory and Practice. New York/London: Routledge, 1995.

- Cooper, B. “Chick Flicks” as Feminist Texts: The Appropriation of the Male Gaze in Thelma & Louise. Women’s Studies in Communication 2000, 23, 277–306.

- Cowie, E. Representing the Woman: Cinema and Psychoanalysis. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1997.

- Creed, B. The Monstrous‐Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis. New York/London: Routledge, 1993.

- Douglas, J. Wooden Reels and the Maintenance of Virtual Life: Gaming and the Death Drive in a Digital Age. ESC 2011, 37, 85–106.

- Dubois, D. “Seeing the Female Body Differently”: Gender Issues in The Silence of the Lambs. Journal of Gender Studies 2001, 10, 297–310.

- Elliot, A. Psychoanalytic Theory: An Introduction, 2nd edn. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002.

- Fink, B. The Lacanian Subject: Between Language and Jouissance. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1995.

- Freud, S. Introductory Lectures on Psycho‐Analysis, trans. J. Strachey. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1966.

- Freud, S. An Outline of Psycho‐Analysis, trans. J. Strachey. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1970.

- Gabbard, G.O. Psychoanalysis and Film. London: Karnac Books, 2001.

- Gordon, A.M. and Vera, H. Home and the Superego: The Risky Business of Being Home Alone. PsyArt 2016, 20, 124–39.

- Gunn, J. On Social Networking and Psychosis. Communication Theory 2018, 28, 69–88.

- Gunn, J. and Hall, M.M. Stick It in Your Ear: The Psychodynamics of iPod Enjoyment. Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies 2008, 5(2), 135–57.

- Hesling, W. Classical Cinema and The Spectator. Literature Film Quarterly 1987, 15, 181–9.

- Hoedemaekers, C. Viral Marketing and Imaginary Ethics, or the Joke That Goes Too Far. Psychoanalysis, Culture & Society, 2011, 16, 162–78.