3 Failure to Consider All Costs of the Operation

Several examples are provided that demonstrate the mistake of failure to consider all costs of an operation. A raw material may be purchased from a non-local vendor and the freight is not included in the purchase price for some reason. The raw material could be a new experimental product with a high waste factor that is not included in the purchase price. There could be unforeseen situations that occur during manufacturing or processing, which are not included in the pricing. It is for this reason I recommend that critical thinking should be employed before any process change to determine any potential problem that may occur to prevent unforeseen costs or delays to enable a solution.

The first real job I obtained after graduating from college was working for a company that produced modular kitchen cabinets and vanities. Included were oven and utility cabinets that were not produced until an order was received because of the difficulty of the production, assembly, finishing, and packaging of these items and also their size and the number of unique components.

The company produced to inventory for several reasons: first, it had operated in that mode for a long time. Although this method of manufacturing had several advantages, it also has its disadvantages. The advantages were it enabled industrial engineers to minimize setup cost per piece to almost zero by scheduling a large batch of parts to be produced (thinking was that the parts would be used eventually) and it enabled PAs to minimize raw material costs by purchasing large quantities of raw material at a time (thinking was that the material would be used eventually). Second, the company had just constructed a large expensive warehouse for finished goods that had to be used, and sale of items was the function of the marketing and the sales department. Disadvantages included the cost of the extra raw material inventory, the likelihood that the raw material inventory would be damaged or become obsolete, and the payment of insurance and taxes on the inventory itself and the building to accommodate the inventory. The most important disadvantage was the color stain on the finished cabinets; although packaged in a corrugated container in the warehouse the color would change due to weather conditions over time. “Last in, first out” was used to schedule shipments.

Oven and utility cabinets, being labor-intensive and difficult to produce due to their size and unique components, were produced only as ordered, and could be shipped with base and wall cabinets that were produced a year or more earlier. Upon installation, the installers and customers realized the stain mismatch and the company was forced to install new recently manufactured base and wall cabinets at no cost to the customer to match the newly produced oven and/or utility cabinets.

During the 1960s and 1970s, International Business Machines (IBM) began producing computer models, the 1440 and the 360, that enabled material requirements planning (MRP) to become a reality. IBM offered new software MAPICS that offered MRP, a system that enabled a manufacturing company to produce to order instead of producing to inventory as it had done previously. This was achieved by exploding (decomposing) a bill of materials into its individual components, separating dependent demand from independent demand based on coding, calculating the need for lower-level inputs (independent demand) and either alerting the PA or placing an order as needed [13]. This enabled the assembly, sanding department, and finishing room to finish a complete kitchen at one time. Inspection of a complete kitchen or bathroom occurred before packing and shipment. This eliminated complaints due to stain mismatch since all cabinets were assembled, sanded, and stained at the same time. In the machine room, mass production was undertaken on common parts and minimum production on unique parts to ensure that the entire order could be produced together.

This costly mistake because of a stain mismatch was easily avoidable and occurred as a result of lack of critical thinking. When a company maintains a large finished goods inventory, the cost of excess inventory must include the cost of maintaining the inventory, the tax on the inventory, the potential damage that can occur, the possibility of obsolescence of the inventory due to changes in the market or the material itself, and the loss of interest on invested capital. These costs must be summed and compared to the benefits of just-in-time production and inventory systems.

Another costly mistake occurred as a result of the purchase of a computer numerically controlled (CNC) fabric cutter. The machine was to be used in a plant located at a small rural town in the middle of nowhere. The closest airport was at least a two-hour drive depending on traffic. Due to the price difference of approximately 25K between the one made overseas and the one produced in the United States, it was decided to purchase the machine produced overseas. The machine was received but did not meet the US electrical requirements as specified in the purchase order but met the requirements of the country in which the fabric cutter was manufactured. Also, the technical manuals for the fabric cutter were in the language of the country in which the cutter was manufactured, which in this case was Spanish. Guess how many people in the rural small town in the middle of nowhere knew Spanish—none.

The first thing that had to be corrected was the electrical requirements. Since there was no locals who knew Spanish, the company had to find an electrician who knew Spanish. Needless to say, there were not too many local electricians, and those who did exist had to come from a distant community and charged much for their time and travel.

The machine was finally cutting fabric to everyone’s satisfaction. Then there was a malfunction, and since the technical manuals were in Spanish, the maintenance people in the plant had no clue as to how to make necessary repairs. A telephone call to the manufacturer was essentially useless because of language differences. Maintenance personnel from the manufacturing company were flown over to make repairs. Of course, the repairs were not covered under warranty because of shipment—whatever excuse can be contrived—so the difference in price was becoming less and less. Of course, the maintenance personnel needed to stay in first-class accommodations, and vehicles and meals provided during their stay further reduced the savings. Eventually, the maintenance personnel left and returned home. Due to the maintenance department’s inability to make repairs as needed, the maintenance crew from the manufacturer became almost regular but extremely expensive visitors. When the machine was not cutting fabric, the plant had to resort to the previous costly practice of manually cutting fabric.

This mistake was definitely avoidable. The purchaser did not use critical thinking to evaluate all potential problems that could result. It did not take many round trips for several people from Spain and accommodations plus lost production to pay for the difference in the two machines. One cannot simply look at the purchase cost but must consider all the factors involved.

The mistake was not due to the machine being foreign-made. It was due to the failure to critically think about the situation to determine what could go wrong with the purchase, particularly when it was foreign-made. The primary things that could go and did go wrong were problems related to maintenance and repair parts since downtime on the machine seriously affected productivity and costs.

Several failures acting together resulted in this mistake. One was the failure to consider all aspects of the project. Questions that should have been asked initially were the following: (1) Why is the machine less costly than its competitors? (2) Where else is this machine being used? (3) What about training and maintenance on this equipment since it is foreign-made?

Another was the failure to ask for advice. This CNC fabric cutter was new technology for this facility in the middle of nowhere. Maintenance needed to be involved initially in the decision-making in order to establish a preventative maintenance program, to understand its operation and to have its manuals translated into English. The availability of technicians and repair parts for all equipment regardless of its durability was not considered. If it was the only machine that was to be in the United States, then the decision should have received additional scrutiny because training and acquisition of repair parts would become much more difficult.

Another possible failure was a human factor and the pressure from the management due to potential cost savings. This facility was facing extreme pressure to reduce costs due to competition and the use of this fabric cutter would save direct labor and material costs by a reduction in waste. At that time, fabric was the most expensive cost of furniture and a reduction in its costs combined with a reduction in direct labor would provide the competitive edge needed.

This mistake is a combination of several failures: not considering all aspects of the project, failure to ask others for assistance and pressures from outside. However, the failure most responsible for this costly mistake was the failure to take all aspects of the project into consideration. If this had been done, other factors would not have been significant. The motivating factor in this decision was the huge price difference between the two machines. As I had told my students many times, it is not what you pay but what you get for your money.

To emphasize the validity of that statement, I had a company car in the early 1970s with a slant 6 engine with an automatic transmission. It seemed as if the engine was on life support but someone forgot to provide the necessary power. It did not look forward to its daily activities. As a result, it rewarded me by its sluggish performance and turning into a gas station of its own accord. Acceleration from 0 to 60 required a day, so it was amazing that more rear-end collisions did not occur when entering interstates. Mechanics at the shop knew that I was frugal, a nice word for cheap, and challenged him to use unleaded supreme gas. Their challenge was that the use of gasoline over regular unleaded would result in better performance and mileage. Being skeptical and curious at the same time, I took on their challenge especially since he had a certain brand of a company credit card and did not personally pay for gas. This was the only change.

In the first month, I used a certain brand of regular unleaded gas at various prices, traveling about 4,000 miles a month. During that month, I maintained meticulous records and used a certain brand of an unleaded supreme during the second month, again traveling about 4,000 miles keeping detailed records paying various prices. At the first of each month, oil and filter were changed, tires were rotated, and air checked. The only thing that changed from one month to the next was the type of gas used. The cost of gas per mile was identical to the fourth decimal point, proving that despite the higher cost per gallon, the variability in the cost per gallon, and the gas mileage was increased enough to offset the higher cost per gallon.

This experiment confirms in practice what I knew in theory and has conveyed to students, fellow employees, and essentially anyone who will listen. It is not what you pay but what you get for your money.

On a late Friday afternoon, I had a job interview with the plant manager of a furniture plant that had been in business forever. The plant produced a traditional line of bedroom and dining room furniture. After speaking with him for a few minutes, the plant manager told me that he was going to save bazillions by reducing 25 percent of the material costs. I asked how he was going to achieve this feat. He responded that he was going to replace all the unseen components of wood in furniture from whatever was being currently used to sweet gum. Sweet gum was less than half the price per thousand board feet of the least expensive grade of lumber he was using at the time.

Several weeks before the job interview, I had paid a tree removal company an amount resembling the national debt to remove a sweet gum tree next to his house and cut it up into two-foot sections so that it could be split for firewood. I was unable to split it, despite weighing 160 pounds of pure muscle. With a log splitter powered with a zillion horsepower Cummings diesel engine, I do not think I would have experienced much success. I asked the plant manager if he had ever tried splitting sweet gum and of course his response was no. He then told me that engineers that he spoke with at various woodworking machine companies indicated that he should not have a problem. I asked if he was going to try it on a small scale just to make sure that it would work as he anticipated. His response was that he had not. What was I thinking?

In addition to the difficulty in splitting, other problems exist with sweet gum. Although there is ample supply, little is seen in sawmills or furniture plants. One problem is that it shrinks or warps in all directions because the material has interlocked grains [14].

This costly mistake was entirely preventable had the plant manager employed critical thinking to question the cause that sweet gum was half the price of the least expensive grade of lumber. This additional waste would more than compensate for the lower price. As I advised my students, it is not what you pay but what you get for your money. Most of the time, you can pay somewhat more and save money in the long run. As much as possible one must always be aware of incremental costs to enable comparison with incremental revenue.

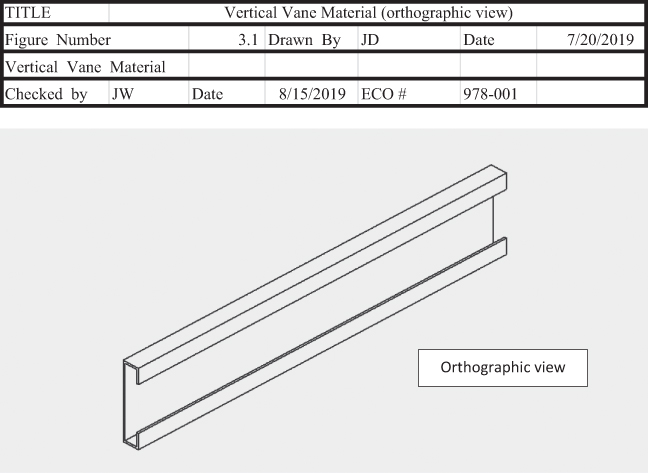

One plant in which I had the opportunity to consult produced vertical window/door coverings used to primarily cover sliding glass doors. This company purchased plastic material in eight-foot lengths into which various items were inserted, such as fabric and metal.

Slots for hanging above the sliding glass doors were then punched into these inserts to enable drawstrings to be attached for the closure of the coverings. The median length of the material sold was 84 inches with a standard deviation of exactly 1 inch. The raw material was priced and purchased per linear foot.

The process consisted of receiving the raw material in the warehouse, retrieving it by one person, and bringing it to the first station in the assembly line, which is the cutting table, cutting to length and discarding the waste (mean of 12 inches into an adjacent trash container and paying for waste disposal), punching one end to accept the plastic insert and drawstring, moving it to the next workstation that attached the plastic inserts into the vanes, placing it onto a conveyor to enable assemblies to be added at the next workstation inside the headstock that enabled the vanes to rotate vertically 180°, returning it to the conveyor as needed to enable quality assurance (QA) to perform an inspection to guarantee that the vane quantity was correct and the mechanism inside the head assembly functioned, and finally packaging the product at the next station for shipment.

The amount of vane material purchased exceeded 100K linear feet per year. The PA advised me that he was in the process of converting from purchasing 8–12 linear feet lengths and that he was going to save the company an extraordinary amount of money. At first, I thought he was joking but when I realized the PA was serious, I tried to make him realize when several factors added together, the purchase of the additional four feet resulted in the company losing money on the product. Instead of disposing of an average of one foot per blind, now the company would throw away five feet. The costs of disposal would be multiplied by a factor of five, and the raw material which could currently be handled by one person would now have to be handled by two people due to its length, doubling the costs of receiving and bringing it to the first workstation (Figures 3.1 and 3.2).

FIGURE 3.1 Vertical vane material—orthogonal view.

FIGURE 3.2 Vertical vane material—top, plan, and right-hand side views.

This mistake was avoidable if the PA had taken the time to consider the effects that the change would have on the manufacturing process. He did not use critical thinking to evaluate all the possible consequences of the changes. As a professor at the college, I eloquently stated and my statement can be simply paraphrased “every change causes a bump on a balloon—you must look and make sure that the bump you get is smaller than the one that was there, to begin with.” This PA failed to do that. He did not critically think before he acted and thus despite my logical argument, he made a costly mistake for the company and himself. Not only did the mistake cost the company many dollars but also the loss of his job.

While working for a large office furniture company as a manufacturing engineer, one of the many responsibilities I had was to enter the bill of material, routing into the computer system and certifying its accuracy. The frame for a new product was a purchased part that was priced free on board (FOB) vendor, which means that the customer is responsible for paying the incoming freight. The frame was powder coated with aluminum color before shipping and the quality was guaranteed to be 100 percent usable. Powder coating is a method of finishing that is applied as a free-flowing dry powder and then allowed to cure under heat to form a skin, which is a hard finish that is usually more durable than most other type of finishes.

Quality inspection of initial shipments revealed that usable products ranged from 60 to 85 percent. Inspection required 1.27 man hours per frame. I disagreed with the PA on the pricing terms and thought that the cost should be the FOB plant to enable that the purchase costs from this vendor could be easily compared with the quote from other vendors should any be located. Because the waste factor was high and varied, I used a special technique to set up the bill for the purchased frame. A bill of materials (BOM) comprises the components and quantities to manufacture or repair a product or service. The BOM consisted of the purchased frame, a waste percentage which was the mean of wastes from the most recent five shipments to include the cost of scrap, the inspection labor cost based on the waste percentage multiplied by the mean time for inspection, and the freight cost, which was the mean of the most recent cost of the last five shipments. As the vendor improved his quality, the inspection rate, freight cost, and frame cost would decrease. Using this special technique, the quality factor and freight changes were easy to track.

I discovered a local vendor who not only guaranteed 100 percent quality but also next-day delivery, FOB plant. The delivery guarantee applied regardless of the order quantity. The only problem was that the price was $14 more per frame than the existing vendor. I gathered data on incoming freight costs, quality inspection costs, costs due to disruption in production as a result of stock-outs, and long-term losses that the company would incur if the company remained with the current vendor. The only response from the PA was the vendor would improve. I responded, “What guarantee does the company have that the vendor would improve to the point that he will be as cost-effective as the one I discovered and how much money would the company lose before the existing vendor arrived at that point?”

The situation was the result of the failure of the PA to perform research to determine the vendor’s capability of meeting or exceeding the required quality and quantity demands. There are several factors that contributed to this avoidable situation. First is that the PA failed to research all potential vendors and factors other than the purchase cost. At a minimum, this research should have consisted of plant tours, speaking with plant employees, discussions with existing customers, reviews with better business bureaus, chambers of commerce, etc. In my experience, more can be paid for your product if that additional cost can be justified. In this situation, the reduction in waste alone was sufficient to offset the additional cost of the frame. The additional savings that would result from the reduction in freight costs and incoming inspection costs would have added to the company’s gross profit. Time could have played a role, but it did not since the product had been in development for more than a year. A factor that contributed to the mistake was the failure to ask for help from experts. The product was to be produced in what has been historically the center of the furniture industry in an existing company plant. No employee in that plant was asked for their advice or input. Worse yet is that the PA did not make a trip to the area to visit many potential vendors. A combination of numerous factors resulted in this mistake, but the overriding one was the failure to consider all costs of the operation which would have included additional waste, the additional cost of inspection, freight, and inventory.

Inspection costs and costs to return a defective product, costs of production interruptions due to stock-outs, and costs of carrying extra raw material inventory due to the variability in the quantity of acceptable order received needed to be added to the purchase cost to obtain the actual cost of the purchased frame.

Another mistake that I witnessed involved a PA concerning the item on the bottom of an office swivel chair, a caster. There are five casters per chair. At one time, there were four but these chairs easily tipped over and could no longer be produced. Changes to the materials and/or processes by which a chair was processed must be approved by all involved including marketing, purchasing, engineering, quality, and all levels of management. The process by which these changes occur is the Engineering Change Order (ECO) system; in most companies with multiple plants, this system is electronic. I received an ECO to change from the current vendor to the one in a different country. The cost difference was $0.01 per caster. The caster was priced FOB manufacturing plant, which meant that the company for which I worked was responsible for paying the freight from this foreign country to the facility I worked. This compared unfavorably with the terms of the current vendor which was FOB in this facility.

All other plants in this company signed the ECO, signifying agreement with the change. I did not sign the ECO and indicated the following reasons:

There was no attached documentation indicating that the caster from the new vendor was of good quality as the existing caster.

There was no documentation indicating that a discussion had occurred with the existing vendor to which a competitor had provided a lower quote, and the existing vendor had been given an opportunity to meet or exceed it.

The company I worked had been conducting business with the current vendor for many years with no quality or delivery concerns.

My opinion was as much manufacturing as needed to be retained in the United States as possible.

The PA was not happy with the response, but appreciated the honesty. Several weeks later, I received a call from a fellow engineer from a sister plant in another state asking if the plant at which I worked had any casters from the original vendor. I responded that the plant did but when asked why, the engineer stated that the first shipment from the alternate vendor passed inspection and performed as expected but when the cartons from the second shipment were opened, all that could be seen were plastic components. The casters had apparently broken apart in shipment. I checked with the material planner in his plant to determine how much, if any, could be shipped to help a sister plant. The material planner called the fellow engineer and told him that the plant would ship as many as possible without jeopardizing that plant’s shipments. The plant at which I worked placed an order with the original vendor for as many casters as possible and deliver these at the earliest.

Saving a penny per caster seems negligible, but one must be aware that there are five casters per chair. The company produced over 6,000 chairs per day in their different chair plants, so a change was justifiable if proper conditions were met. However, this mistake resulted in the inability to ship chairs for many weeks resulting in many dollars lost and prestige which cannot be measured in dollars. I would not want to explain to a customer that his chair could not be shipped due to the desire to save a penny a caster. The only plant that did continue to produce and ship chairs without interruption was the one that did not change casters. The motivations of the plant to not approve the change were that the freight costs from the new vendor and the cost to carry the needed inventory to cover the additional travel time would exceed the penny difference in the cost of the casters.

This costly mistake could have been avoided. The PA did not include all costs of the caster and for some reason failed to use critical thinking to determine all potential possibilities that could result from this decision. Additional costs that should have been included were freight from the new vendor as well as the cost of the additional inventory that would be needed to ensure that there were no stock-outs. Once the company was unable to ship the product, lost revenue must also be added to the costs. Additionally, the company for which I worked had been purchasing from the vendor for many years without quality or delivery issues. One must treat vendors as one treats employees—with respect, honesty, and dignity.

These mistakes resulted from the failure to understand the importance and significance of human factors in the workplace. One such human factor is lack of self-assertiveness. Another contributing human factor could have been lack of team work. I encourage readers to investigate this topic further by reading the information under Human Factors in the Appendix section of this book and carrying out further research and coursework.