19

Signals versus Noise

We've often said that you can't turn on a financial news station without hearing crypto mentioned incessantly. That, and with constant failures in the world of crypto companies (just like in the early days of the Internet), there is a lot of information out there. We assert that most of it is noise, and our goal now is to give you the tools to sort through the barrage of information to find the true gold. Our goal is to separate the signals from the noise.

All That Glitters Is Not Gold

We live in a world in which crypto has been seen to be the latest, greatest, and perhaps most accessible get‐rich‐quick scheme. It seems obvious, given the stories of teens who, in 2012, invested a few hundred dollars to buy bitcoin and are now driving Lamborghinis. It begs the question, which is sourced from a nonflattering combination of fear, greed, and envy, “Why can't I do that?”

We're happy for those who had the wisdom/hopefulness/foolishness to look ahead 10 years ago, take a risk, hold on for a decade, and suddenly reap the benefits of such a speculative investment. However, that period is over, so we need to look ahead. Is it possible to generate 1,000× gains on a crypto asset? Yes – but picking those is very, very hard to do. At the time of this writing, CoinMarketCap lists just slightly less than 9,500 crypto assets in the marketplace. That's a lot of assets, so let's see if we can narrow that down to a reasonable subset of viable investments.

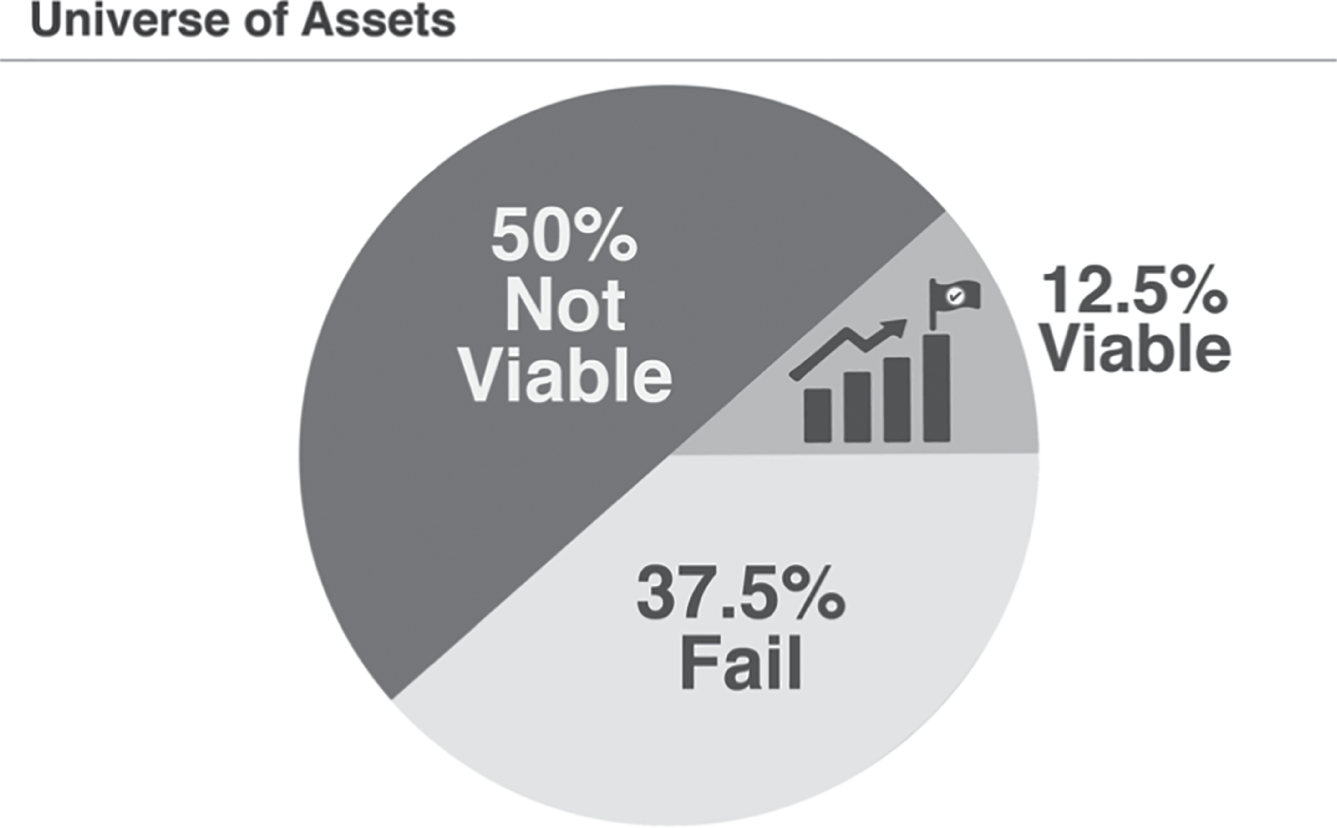

First, let's weed out the copycats – the get‐rich‐quick schemes. It's impossible to know the exact number of these, but we can do some quick calculations. Dogecoin, for example, was created as a joke. Certainly, people have made money on it, but it has no real differentiation and no real use but, hey, money is money. Because of its popularity and acceptance, let's call it “real” for a moment. After a quick look again at CoinMarketCap, we find over 100 coins with the name Doge in it, each expecting to be the next big thing. These are schemes created as a copy of something that was originally created as a joke – and it goes further than that, as one of the more successful copies of Doge was Shiba Inu, another meme coin that basically copied Doge. It gets worse because, looking at CoinMarketCap again, we can see over 100 additional coins with the name Shiba in it. The simple fact is that there is almost no barrier to entry. Anyone can copy any other blockchain and make another “get rich” coin. So, even if we consider Dogecoin and Shiba Inu “legitimate,” we have 200 copies for each of these coins, or a ratio of 1/100, legitimate/copies. The proper ratio of legitimate coins to copies is probably not 1/100, but it's certainly a lot. We can't identify all of these, but we're going to go out on a limb and call it something like 50%. This assumption brings us down to 4,750 legitimate blockchain projects represented by tokens. We highly doubt that there are almost 5,000 legitimate public blockchains right now but for the sake of argument, let's say there are. We know from our Chapter 18 discussion of liquid venture that 75% of all viable technology startups fail. If we apply this metric to our universe of 4,750, there are now 1,187 viable projects that will stand the test of time, or a little over 10% that will make it (see Figure 19.1).

The point is that we believe that the universe of viable assets is a minimal subset of the assets out there. So how do we choose which ones to invest in? It depends on what you are trying to do. Are you trying to pick something for a penny and hope it becomes a dollar? If so, we suggest you save some time, head over to the Vegas Strip, and start putting some money on roulette. You will have much better odds, in our opinion. If, on the other hand, you're looking to make investments in technology that will become foundational, then we do have some criteria to separate the signal (what is valid) from the noise (everything that you hear).

Figure 19.1 Viable Crypto Assets (Estimated)

Sound Assets

First let's look at the two most important criteria of sound money. One, which we discussed in Chapter 16, is scarcity; the other is acceptability. As a quick review, scarcity is important because if something is everywhere, or ubiquitous, and everybody has it, it will probably not have immense value. Like sand. Or rocks – rocks are not scarce. Gold, however, is. This is one of the reasons gold has value. Scarcity is not the only important property, because objects that have value must be accepted.

Acceptance points to the fact that people are using, or at least want to use, whatever that asset is. Gold is scarce and accepted. Radioactive waste is also scarce, yet people really don't want to deal with it (unless, of course, you have a radioactive waste company). Radioactive waste does not have acceptance as something of value. Now, if suddenly you could power your car with this waste and it would clean the environment, we might have a different understanding of acceptance. Since we don't, it allows us to illustrate that these two principles are key. We're noting this now because these principles apply not only to money but also to technologies. With that background, let's now look at the characteristics of viable projects.

What Makes a Crypto Asset Valuable

We suggest you consider seven core characteristics when selecting crypto assets as an investment; two noted above, scarcity and acceptance, and five others. The complete list then is:

- USP

- Moat

- Team

- Market capitalization

- Acceptance

- Scarcity

- Regulatory risk

USP

USP stands for unique selling proposition. A USP is what distinguishes a product or project from all others in the marketplace. To succeed, differentiation is required. As an example, let's look at the USP of the first two popular electric cars. The Tesla S differentiated itself by being the first luxury electric car. The Toyota Prius, on the other hand, was the first affordable electric car of quality. Both differentiated from the marketplace by being electric, and they differentiated from each other based on price. Back to blockchain, just about everyone conflates crypto assets with cryptocurrency, but we find them to be distinct. Cryptocurrencies are tokens that are related to blockchains that are intended to be money. Crypto assets are tokens that relate to blockchains that are not intended to be money, for example, a smart contract platform.

Bitcoin is a blockchain that is being used as money, as an exchange of value, and that's pretty much it (it is a money use case). At this point, it is one of hundreds or maybe even thousands of crypto assets that don't do anything but act as an exchange of value. From our purview, Bitcoin solved the money use case. However, let's look at some of the copies. Litecoin is perhaps the most famous. It is a fork (copy) of the Bitcoin blockchain, and it modified some of the ways the Bitcoin blockchain worked and, yes, it has a faster confirmation time, but we don't see this as being sufficient differentiation. At the end of the day, it doesn't do anything that Bitcoin doesn't do.

Neither does Bitcoin Cash, BitcoinSV, Dash, Digibyte, Dogecoin, and so on. Sure, people have still made money on these coins, but we must consider whether they provide something new and different. If an offering lacks differentiation, it won't succeed. Will they stand the test of time? Some tout better speed or privacy, which might be important, but is it enough to make that coin stand out uniquely? In the case of apples‐to‐apples comparisons, on the surface, there isn't much of a USP for any of these.

Case in point, if I open up a coffee shop next to Starbucks and I serve essentially the same product but have a different logo – maybe an orange whale instead of a green mermaid – what will incentivize people to buy my coffee? Sure, some will because it's not Starbucks but, in general, Starbucks has solved the quality, consistent coffee problem and established such a marketplace that without differentiation, it's hard for new coffee shops to compete. Some now focus on pour‐overs, have a more casual environment, better pricing, or specify the essence of their roasting of beans. Some are much higher end. These shops may succeed, but copycats that produce a similar product with similar quality and price simply won't compete.

With regard to nonmonetary assets, let's revisit smart contracts. Smart contract platforms include projects like Ethereum, Solana, Cardano, Algorand, and many others. The overall goal of a smart contract platform is to allow the building of blockchain applications. They are toolkits to launch other blockchain projects, which include, but are not limited to, NFTs, DeFi protocols, Metaverse platforms, and, in general, other blockchains. Ethereum was the first to popularize the concept of smart contracts, and that was their USP. Ethereum also became notorious for being expensive and not very scalable. While the Ethereum Foundation is admirably working to resolve these problems (and may indeed have done so by the time you read this), they opened up the door for other players to compete. Solana, a competitor, ostensibly does the same thing as Ethereum but proposed a new type of consensus mechanism. Where Ethereum initially used proof of work, then migrated to proof of stake, Solana considered the idea of a proof of history mechanism. Proof of history uses blockchain timestamps to determine consensus much faster and at a lower cost. Solana brought a unique selling proposition to the table. Tron, on the other hand, basically copied Ethereum and (upon launch) didn't bring anything unique to the table. We argue that Tron has no distinguishable USP of significant value.

Moat

We all know of medieval times when kings and queens would reside in towering castles to rule their kingdoms. These images of lavish stone fortresses almost always are envisioned with a drawbridge that allows people to cross over a body of water – a moat – that surrounded the castle. The purpose of a moat is quite simple: to make the castle difficult to attack. The arduous task of swimming through a body of water to get the right to scale a stone wall while castle guards shoot arrows down at you is enough to scare most attackers off. Those who did attempt to overrun the compound found that the cost of life was significant and that traversing a moat is not that easy.

That's pretty dramatic; however, the principle of a moat as a characteristic of a project remains the same. If a project can be easily attacked, it becomes more vulnerable, so we want to consider projects that are defensible and have a moat. In 2009 it could be argued that Bitcoin did not have much of a moat. Anyone could copy the chain and attempt to build a better Bitcoin; in fact, many did. Fast‐forward, however, and Bitcoin now has a sizable moat, given by a 13‐year history, a $1 trillion market cap at its peak (as of this writing), the largest mining community in the world, and growing acceptance as money. Now, the moat is formidable. Its nearest competitor, Litecoin, had, at its peak, a $21 billion market cap, and very little acceptance during the same periods. Where Bitcoin has had continued strong support from the technical community Litecoin has languished. Even the founder of Litecoin, Charlie Lee, sold all of his Litecoin in 2017 – not exactly a vote of confidence. With that, by the way, many coins are competing with Litecoin for the position of being the “second” blockchain money, but we have to note here that we believe stablecoins (crypto assets pegged to another asset, such as a U.S. dollar) will ultimately solve the problem of exchange of value, while Bitcoin will most likely become a store of value for the digital world. With these in place, we just don't see that there's much of a chance of a secondary coin being viable over the long term.

If we look at smart contract platforms, the moat here seems primarily to be the technology. Everyone is trying to build a better (scalable, faster, less expensive) smart contract platform. Some, such as Solana, brought proprietary technology to the table, which became a part of their moat, because this technology is more difficult to copy and maintain. In this case, we see that specific technologies can be a moat themselves. In any case, when considering assets, be sure that they are defensible – if they are easily replicated or attacked, that becomes a problem.

Team

With any new blockchain, new token, or any project of any kind, really, consider that the team is everything. As such, we encourage you to take the time to understand who the team is. Have they successfully executed technology projects before? Do they have significant backing from known venture firms? Do they have credible advisors with a proven history of success?

While the mysterious Satoshi Nakamoto remains anonymous, the code that runs the Bitcoin blockchain has been reviewed, vetted, and is publicly visible and available. This code, known as the Bitcoin core, is maintained by a group of developers, the lead of which is currently Wladimir Van Der Laan, who has been involved since 2011 and who took over the lead role from original core lead Gavin Andressen in 2014. In addition to Van Der Lan, many other core developers maintain the project, and, as there is no “company” behind Bitcoin, these developers are subsidized by grants by well‐known institutions. For example, Van Der Laan's work is funded by MIT Media Lab's Digital Currency Initiative (MIT DCI). Other noted developers have been funded by Square, Blockstream, Gemini, Coinbase, and other major players. In this case, we have a team led by someone with a proven track record of delivering on the code, supported by one of the greatest academic institutions in the world, MIT. Similarly, Polkadot was founded and is anchored by Gavin Wood, a research scientist at Microsoft before becoming one of the founders of the Ethereum blockchain. When considering Polkadot as a project, the fact that it had a lead with a proven track record goes a long way.

Regarding the counterexample, rather than throw anyone under the bus, we'll say that there are many blockchains and many tokens that have been created with teams that are not identifiable, have no history of technological success, or, even worse, have checkered pasts. Know your team.

Market Capitalization

Market capitalization, the overall public value of a blockchain, offers another important metric. This doesn't necessarily demonstrate who the users of a given project are. However, it does show how the market views a blockchain. Market capitalization is calculated by multiplying the number of tokens in circulation by the price of each token. Ultimately, projects that gain acceptance or at least are viewed to have potential will have a higher value per token and, as such, a higher market capitalization. There is an obvious question: If the number of tokens in circulation values a blockchain, why doesn't every project just circulate hundreds of billions of tokens? The short answer is, as we learned from the conversation about scarcity, more of something does not necessarily make it worth more. In fact, too much of anything will almost always depress prices, so this is a self‐correcting system in many ways. Projects that provide value and therefore demand that also have tokens of a proper supply will, by nature, have a higher market cap than projects that don't. Market capitalization measures this balance.

Market capitalization can be tricky, however, because there are many projects such as Dogecoin that, at one point, had a top‐10 market capitalization. While this may seem promising, this coin lacks every other key attribute listed here and, importantly, has not always maintained a strong market cap. We would then extend this concept to consider market capitalization over time. Ethereum, for example, has had the largest market capitalization of any Layer 1 smart contract platform since its inception. Other similar protocols have come and gone. Some have briefly danced alongside Ethereum and then have been abandoned. As a guideline, if a token has less than $500,000 in market capitalization, we would, in general, be very wary before adding it to our portfolio.

Acceptance

Acceptance in the world of crypto assets – particularly technologies – boils down to a simple test: Is anyone using the platform? For many years, in the case of Bitcoin, no one was, and this was one of the main concerns of detractors. Now, however, you can use bitcoin at Microsoft, Whole Foods, Starbucks, and many other retailers. There is also a new trend where homebuyers can spend bitcoin to buy real property. In addition, you can also use bitcoin to pay taxes in some states, such as Colorado.1 Every day there is more acceptance. Conversely, although one can use bitcoin, other alternative cryptocurrencies are generally not accepted at these retailers. This is important.

On the platform front, one only has to look at Ethereum to see that it has been the platform of choice for building blockchain projects since its inception. It has acceptance. Developers have constructed DeFi apps, NFTs, metaverse projects, decentralized exchanges, and many other assets on this blockchain. Recently, however, we've seen other chains start to gain traction, so this will be an exciting space to watch. Many DeFi projects moved to Solana in consideration of Ethereum's scalability concerns, and others, like Algorand, have recently cemented deals with FIFA. When examining any project, look to see who is using it.

Scarcity

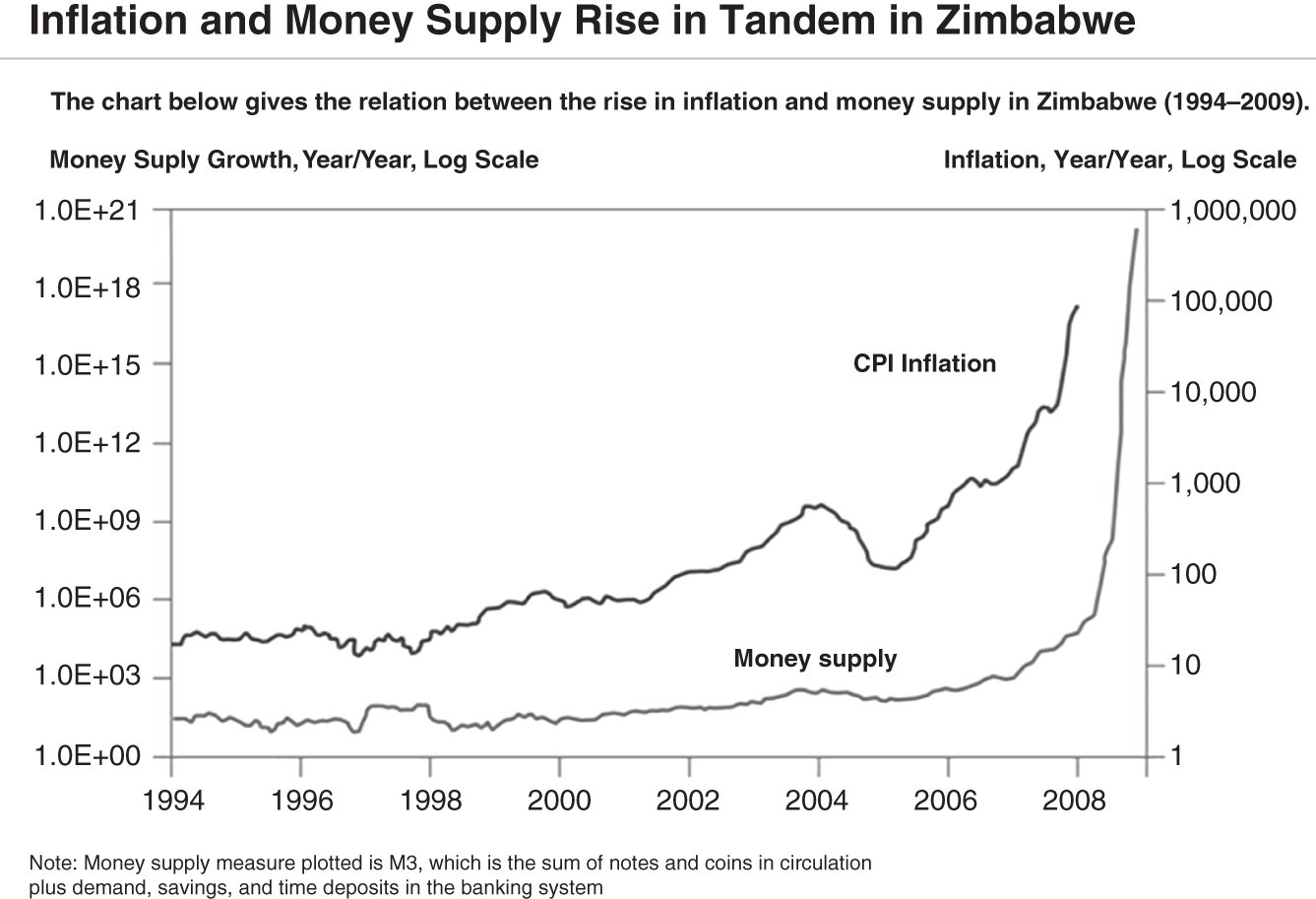

As noted earlier, scarcity is an essential characteristic of sound money, and things that are scarce tend to have more value over time than things that are not. Consider what has happened with the U.S. economy over the past years. During the pandemic, the U.S. government printed approximately 40% of all dollars in circulation in a matter of a few years. That's a staggering number, and it's no surprise that, with inflation taking hold, we see that the average dollar is worth less than it was a year ago. In fact, as of this writing, it's worth about 9% less as measured by the July 2022 Consumer Price Index. Mo' money mo' problems, indeed. You would think that we would have learned, as we see from economies such as Zimbabwe, which realized almost unimaginable inflation, primarily due to overprinting money (see Figure 19.2).

How does this apply to crypto assets? Well, let's take bitcoin as an example. Bitcoin, as we've discussed, has a supply limited to 21 million coins. Period. With 19.2 million in circulation currently, the only way you can get a bitcoin is if someone wants to sell one at the price you are offering. Over time bitcoin has had significant price gains, and we believe this will continue in the future. Ethereum also takes this concept seriously as, originally, an unlimited supply was available. Realizing that this would not promote value appreciation in 2021, a code change was agreed upon by the Ethereum community and implemented in what was known as the London hard fork. Among other things, this code change made Ethereum disinflationary, meaning that coins were being taken out of circulation every time a block was made.

Figure 19.2 Inflation and Money Supply in Zimbabwe

Source: Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe Monthly Economic Reviews.

Conversely, let's consider Dogecoin. There are currently approximately 10,000 new doge put into circulation every minute. We challenge you to name anything with a potential unlimited number of copies, with more and more copies entering the market every day, that ultimately increases in value. That's not how it works. Scarcity drives values in all things, and digital assets, whether money, NFTs, or any other asset, are no different.

Regulatory Risk

In Chapter 6 we discovered that regulators are trying to get their arms around digital assets. It's a whole new world for them, and the SEC and CFTC are duking it out for control. Rather than ban crypto, however, they are really looking to ensure that it's implemented safely. The main thing the government wants is to ensure that crypto assets, which are the tokens related to a blockchain, are not sold like securities. As a quick callback to our regulatory chapter, securities are assets sold with an expectation of a return, and they are heavily regulated.

Let's say you take a functioning crypto asset like a token, and say, “okay, it's like bitcoin.” Then you conclude it's a commodity, therefore you're good to go and you buy some of the token, expecting a return. We would argue that process matters, and it's hard to qualify one‐offs or solitary initial coin offerings as commodities. They're not part of a bigger pool of goods that are largely the same. The whole point here is to understand when an asset has the potential to be categorized as a security because, if it does, then you run a risk of the project being challenged – which often means “death by regulation.”

Let's say a digital asset comes into existence via an initial coin offering (ICO), where the offering is tokens in exchange for money upfront before a working network or product exists and where the investor expects to make a return. You're buying a stake in a new thing. It's speculation, and anything that falls into this category is most likely going to be classified as a security and will have to follow securities laws. This is exactly what you don't want to do as an investor, because you run the risk of the SEC challenging any project that looks and smells like a security. We urge you to not get caught up in the hype. Look instead at fundamentals and understand your risk.

Risk is a shopworn concept in finance, and we best understand risk as a continuum. It's important to assess where you are with your project or crypto asset, as an entrepreneur or as an investor, on this continuum. We use seven factors to evaluate regulatory risk for any particular crypto asset:

- Is it a coin or a token?

- If it's a coin, is it mineable?

- If it's a coin, is it decentralized?

- Is it functioning in production?

- Was there an ICO?

- Was it offered in the United States in a public or private sale?

- If it is public in the United States, was there a know‐your‐customer (KYC)/anti–money laundering (AML) measure performed?

We can evaluate answers to these questions and see where we land in the continuum of regulatory risk. The least risky crypto asset is a coin being used in a functioning decentralized blockchain network. A coin by definition facilitates the operation of its blockchain and network. If the coin is mineable, so much the better because it's got different economics than if people bought it in an ICO (or other means) because, in such a case, miners received coins for work. This notion came out when the SEC announced that bitcoin was not a security. This was huge.

Conversely, if it's an ICO that was offered privately with a pre‐mined and centralized token with no KYC/AML performed, there is a very good chance that the SEC could come calling. At the very least we recommend that you use these two endpoints in your continuum and evaluate everything else as they relate to these points.

In a 2018 hearing before the House Appropriations Committee, Congressman Chris Stewart asked SEC chairman Jay Clayton to clarify his view on how regulatory oversight of cryptocurrencies could be split between the SEC and CFTC. Clayton responded:

It's a complicated area. Because, as you said, there are different types of crypto assets. Let me try and divide them into two areas. A pure medium of exchange, the one that's most often cited, is bitcoin. As a replacement for currency, that has been determined by most people to not be a security.

Then there are tokens, which are used to finance projects. I've been on the record saying there are very few, there's none that I've seen, tokens that aren't securities. To the extent something is a security, we should regulate it as a security, and our securities regulations are disclosure‐based, and people should follow those and provide the information that we require.

We don't agree that all tokens are securities, but we do acknowledge that a great many sure look like them upon examination. These are the ones to be wary of. Finally, if a coin is premined and centralized, it's the riskiest type of coin. There are good chances that it has a high regulatory risk of being classified as a security. If the project is decentralized, it will be much less risky because it can be argued it's not a common enterprise. Tokens, by definition, are created on existing blockchains. For tokens the first question is: Is its network functioning? If the token has a functioning network, protocol, utility, or product, then it's less risky and is not a security. This notion emerged when the SEC announced that Ethereum is not a security because it has the features of being an active operating and functioning business enterprise with products and protocols.

The next set of questions revolves around how the crypto asset came into existence. Was there an ICO (money paid to get tokens before it hit the public market)? If so, there's more risk. If it was airdropped or came into existence another way, there's less risk. If there was a public sale in the United States, it's riskier than a private sale. A public sale of a token that did not do a KYC/AML is riskier than one that did. If you have a token that did an ICO and it's not currently functioning and you did a public ICO in the United States with no AML/KYC, then you have the most regulatory risk and you will most likely have to deal with the SEC.

Ripple Labs is in the midst of this as, in December 2020, the SEC sued, claiming they had raised $1.3 billion by selling XRP through unregistered security transactions. Ripple Labs and the SEC are basically dueling it out right now, with the main question being “did they pass or fail the Howey Test?” This will probably be resolved by the time you read this and, if we had to predict, there will be some kind of a deal made. This is of course at the conclusion of a long and drawn‐out three‐year court case, during which the price of the token cratered as well as soared only to crater again. Importantly, no one knows how this will turn out, but, we argue, why take the risk? We specifically avoid investing in anything that remotely resembles a security. We recommend that you do the same.

In addition, we recommend that you stay abreast of regulations – we know that can be a lot and a daunting task, but this universe is evolving. Our hope is that we see slow but steady regulation like the Token Taxonomy Act (introduced in 2021 and still pending), which excludes digital tokens from the definition of a security under federal securities laws. As clarity such as this unfolds you will be able to make more sound investments but, until then, we always recommend a more measured approach. The last thing you want is for your amazing investment to be clamped down by Uncle Sam.

Putting It All Together

We suggest that all of these characteristics need to be taken into careful consideration. Not every asset that grows in value will necessarily have all seven of these boxes checked right at the outset, but we have seen over time that those that consistently seem to stand the test of time do embrace all of these characteristics. A ubiquitous phrase in the crypto world is “Do Your Homework!” Our intent in outlining the above is to provide a framework for you to do just that. Happy studying!