What Is a Global Virtual Team?

In the management field, a team is defined as a small collection of people at work who engage in interpersonal interactions to achieve established goals (Piccoli et al. 2004). According to Johnson and Johnson (1997), they define a team as two or more individuals with the following elements and characteristics: (a) members are interdependent and strive to achieve mutual goals; (b) they need to communicate in order to achieve the stated and agreed goals; (c) members are cognizant of the members’ contributions—who is contributing and who is not; (d) members are assigned with specific tasks, roles, and responsibilities; (e) and the life span of membership is limited because members are usually assembled on an ad-hoc basis.

Teams are an important means of engaging an organization’s creative and problem-solving capabilities. For an organization to be competitive and resourceful, they need teams that can create synergies among coworkers. Eliciting ideas from several minds often leads to more creative solutions than one person working on a task alone. As the saying goes, “Alone we can do so little, together we can do so much!” (Helen Keller, American political activist). Kenneth Blanchard supported this idea in his wellknown book The One Minute Manager (1982), in which he says, “None of us is as smart as all of us.”

The development of computer-mediated communication (CMC) technology and its introduction into multinational corporations (MNCs) have given rise to a different form of teamwork called global virtual teams (GVTs). To fully exploit this novel work structure, MNCs also need to develop new practices, procedures, standards, and tasks for teams that depend on CMC technologies for their daily work routines. This phenomenon is known as the digital-wave workspace and is becoming prevalent in MNCs.

According to Jarvenpaa and Leidner (1999), GVTs have three characteristics: (1) they are culturally diverse, (2) they are geographically dispersed, and (3) team members use electronic technology (e.g., email) to communicate. Jarvenpaa and Leidner (1999) define GVTs as an ad-hoc or temporary team in which team members do not have a shared history of working together as a group and are unlikely to do so again in the future. Yusof and Zakaria (2012) further suggest that GVTs can be defined as teams that (1) are noncollocated and thus can work across different organizational boundaries, functionalities, and/or geographical locations; (2) use information communication technology (asynchronous and/or synchronous) to collaborate and communicate for work purposes; (3) experience time zone differences; (4) work on tasks or projects that allow temporally flexible schedules; and (5) have team members from diverse cultural backgrounds.

For all of these reasons, GVTs can present complex and varied challenges. For example, imagine working with strangers, without any knowledge of their past performance by which to judge their reliability and trustworthiness. Imagine engaging with team members for extended work hours or even during normally off-work hours due to being in different time zones. Imagine dealing with diverse communication styles, decision-making patterns, negotiation approaches, and leadership traits because team members come from different cultural backgrounds. Imagine trying to defuse a conflict when collaboration and competition are interpreted differently because of culturally rooted values, attitudes, and perceptions.

In order for MNCs to have high-performing GVTs, they must rely heavily on CMC, since geographical distance is no longer a barrier to virtual cross-border collaboration. However, coping with cultural diversity in a work setting requires different skills—for example, building trust is an essential element in team effectiveness (Zakaria & Yusof 2015; Klitmoller & Lauring 2013), but cultural diversity can either promote or hinder the formation of swift trust in a virtual work environment (Branzei et al. 2007). In addition, it is important to note that the extent of virtualness varies (Solomon 2012; Kirkman et al. 2004; Zigurs 2003) and depends largely on the need and nature of the collaborative work being undertaken.

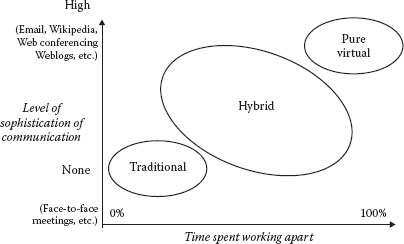

The degree of virtualness has two elements: (1) level of communication and (2) time spent working apart (Griffith & Neale 2001). As shown in Figure 2.1, pure virtual teams (upper right) never meet face to face regardless of the communication tools that are used. At the other extreme (lower left) are traditional or face-to-face teams that do not use any CMC tools at all. Given the current state of technology and globalization, both extremes are nearly nonexistent (Griffith et al. 2003). The hybrid environment or hybrid collaboration is most common, where communication takes place face to face, as well as virtually (Nunamaker et al. 1998; Warkentin et al. 1997).

These several definitions of GVTs suggest that team members differ not only in the degree of virtuality (as shown by their use of information and communication technologies as their primary means of communication) but also in terms of their national and cultural backgrounds. Consequently, I define GVTs as separated by time and space but, more importantly, as differing in national, cultural, and linguistic attributes and work structure.

Figure 2.1 Dimensions of virtualness. (Adapted from Griffith, T.L. & Neale, M.A., Informational processing in traditional, hybrid, and virtual teams: From nascent knowledge to transactive memory, in B.M. Staw & R.I. Sutton (Eds.), Research in Organizational Behavior: An Annual Series of Analytical Essays and Critical Reviews, 23 (pp. 379–421), 2001.)

Case 2: Cultural Vignette

You Speak Differently! Diverse Communication Styles

After working with her virtual team for almost ten days, Ms. Kim Hue, a promising young architect from Vietnam, is feeling upset and stressed. This makes her contemplate whether or not her energy and effort have been a waste of time. When a colleague asks her, “What has happened to you? I no longer hear about your enthusiasm and optimism about the eight-week project, are you doing OK?” Kim starts to express her frustration. “It was fantastic in the beginning since all five of my team members from Sweden, the U.S. and Germany was so cooperative. Moreover, considering I am only a junior executive among them, I can tell that they appreciate and respect my ideas as they often support and encourage me to share ideas. I was highly motivated to contribute—to the extent that I said ‘Yes’ whenever they wanted to have meetings late at night or even at two or three in the morning for me, due to the time difference. But yesterday my team leader, Mr. Grisham Anthony, the Swedish guy, sent me a long and harsh email about the problems we encountered. I was shocked and don’t know what to do. He confronted me directly about the issues and he did it in a public space (using email). I am ashamed and embarrassed.” Kim values her privacy and normally employs a subtle or indirect way of addressing a problem. She always tries to avoid confrontation out of a desire to save face by not embarrassing people publicly. What her leader did is unacceptable and upsetting to her, so much so that she says to her boss, Mr. Duong Hou, “If things don’t seem to work out, I will quit this project.” Duong listens carefully to her account of what has happened, then says to her, “Kim, the way Westerners speak is direct and straightforward. That is just the way they communicate. It isn’t mean to be aggressive or rude. You and I, on the other hand, tend to keep to ourselves. My advice is to ignore it, and continue to work as diligently as you have. After all, I chose you since you are the best we have!” With that reassurance, Kim sighs to herself, “Well this is a real challenge for me since I cannot see their facial expressions or hear their tone of voice via email. But perhaps it is just part and parcel of teamwork!”

Branzei, O., Vertinsky, I. & Camp, I.I. 2007. Culture-contingent signs of trust in emergent relationships. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 104, 61–82.

Griffith, T.L. & Neale, M.A. 2001. Informational processing in traditional, hybrid, and virtual teams: From nascent knowledge to transactive memory. In B.M. Staw & R.I. Sutton (Eds.), Research in Organizational Behavior: An Annual Series of Analytical Essays and Critical Reviews, 23 (pp. 379–421).

Griffith, T.L., Sawyer, J.E. & Neale, M.A. 2003. Virtualness and knowledge in teams: Managing the love triangle of organizations, individuals, and information technology. MIS Quarterly, 27(2), 265–287.

Jarvenpaa, S.L. & Leidner, D.E. 1999. Communication and trust in global virtual teams. Organization Science, 10(6), 791–815.

Johnson, D.W. & Johnson, F.P. 1997. Joining Together: Group Theory and Group Skills, 6th ed. London: Allyn and Bacon.

Kirkman, B.L., Rosen, B., Tesluk, P.E. & Gibson, C.B. 2004. The impact of team empowerment on virtual team performance: The moderating role of face-to-face interaction. Academy of Management Journal, 47(2), 175–192.

Klitmoller, A. & Lauring, J. 2013. When global virtual teams share knowledge: Media richness, cultural difference and language commonality. Journal of World Business, 48(3), 398–406.

Nunamaker, J.F., Briggs, Jr., R.O., Mittleman, D.D. & Balthazard, P.B. 1998. Lessons from a dozen years of group support systems research: A discussion of lab and field findings. Journal of Management Information Systems, 13(3), 163–207.

Piccoli, G., Powell, A. & Ives, B. 2004. Virtual teams: Team control structure, work processes, and team effectiveness. Information Technology and People, 17, 359–379.

Solomon, C. 2012. The challenges of working in virtual teams: Virtual Teams Survey Report—2012. RW Culture Wizard. Retrieved January 27, 2016, available at http://rw-3.com/2012VirtualTeamsSurveyReport.pdf.

Warkentin, M.E., Sayeed, L. & Hightower, R. 1997. Virtual teams versus face-to-face teams: An exploratory study of a Web-based conference system. Decision Sciences, 28(4), 975–996.

Yusof, S.A.M. & Zakaria, N. 2012. Exploring the state of discipline on the formation of swift trust within global virtual teams. Proceedings of 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (pp. 475–482). Maui, Hawaii. January 4–7, 2012.

Zakaria, N. & Yusof, S.A.M. 2015. Can we count on you at a distance? The impact of culture on formation of swift trust within global virtual teams. In J.L. Wildman & R.L. Griffith (Eds.), Leading Global Teams (pp. 253–268). New York: Springer.

Zigurs, I. 2003. Leadership in virtual teams: Oxymoron or opportunity? Organizational Dynamics, 31, 339–351.