Edward Hall: High-Context versus Low-Context Intercultural Communication

As an anthropologist, Edward T. Hall (1976) examined the factors that influence intercultural understanding and thus enhance or impede communication between individuals from different cultural backgrounds. His work led him to formulate a cultural dimension called context. Context explains the way people evaluate and interpret the meaning of information that they receive. Hall stipulates that context comprises a system of meaning for information. It provides a model that enables people to comprehend communication forms ranging from the purely nonverbal (such as hand gestures, body language, facial expressions, and tone of voice) to the purely verbal (such as written text or spoken words).

Context is a continuous spectrum that reflects how much reliance a culture places on nonverbal cues in order to communicate: the heavier the reliance, the higher the context. Although context is a continuum, Hall focused on the two poles: (1) high context and (2) low context. Using context as a dichotomous variable highlights the differences in a more distinctive manner. Hall argues that, although people may use both high- and low-context communication, only one style is predominant at any given moment (Gudykunst et al. 1996).

Aside from context, Hall described several other dimensions that vary across cultures, for example, the meaning and importance of time and space. He focused on these two dimensions in his first book, Silent Language (1959), in which he observed variations between cultures not only in language but also in a communication phenomenon that goes beyond the use of language. This language of behavior, which he called silent language, constitutes elaborate prescriptions regarding how people handle time; spatial relationships; attitudes toward play, work, and learning; and more. Hall asserted that people frequently consider “time as an element of culture which communicates as powerfully as language” (p. 128), metaphorically known as time talks. The dimension of space, on the other hand, refers to the notion of a physical boundary that separates every living thing from its external environment, or, as he put it, space speaks.

In his later book, Beyond Culture (1976), Hall introduced the context dimension, another aspect of silent language. In this book, Hall focuses only on context, as it is the dimension with the strongest connection to communication. Context refers to the situational and informational aspects of message sharing; as Hall points out, the ability to glean shared meanings from nonverbal or paralinguistic cues affects communication between people from different cultural backgrounds. Language and the silent language are both critical in establishing common ground (Clark 1996). Obviously, then, communication challenges are amplified when people from different cultural values attempt to comprehend each other’s indicators, signals, and nonverbal or verbal cues (Cassell & Tversky 2005; Pekerti & Thomas 2003).

According to Clark (1996), people establish common ground when they do something together, as a joint activity. When two people carry on a conversation, for example, several joint activities take place as they coordinate, manage, and synchronize their efforts to establish a mutual understanding, or common ground. Language is one of the many means that are used to establish common ground. This can be language in its most basic form, i.e., face to face (spoken), or in various kinds of written settings. The setting in which language is exchanged is known as the medium. In Clark’s study, the medium is electronic and textual or written. Another important communicative element is scene, the place or situation in which the language is used.

Despite the fact that language is one of the most common bases for establishing common ground, it also can be a barrier in situations that rely on computer-mediated communication (CMC), such as email lists or blogs, since the vast majority of CMC is in English (Uljin et al. 2000; Cairncross 1997). Although English is known and used in the international business arena and is spoken with some degree of skill by many, it is not the first language for millions of people across the world. In addition, the slang terms used in one English-language culture may have obscure, opposite, or alternate meanings in another English-language environment. Interestingly, Ayyash-Abdo (2001) observed that the use of English might alter one’s cultural orientation. Other studies have found that, when people use English in CMC, native and non-native English speakers exhibit differences in their discourse preferences and formats based on their cultural values (Uljin et al. 2000). Thus, participants collaborating via CMC need to be cognizant of and sensitive to English-language variations in style, format, tone, salutations, and closings, as these cues may affect the accuracy of their communication (Bloch & Starks 1999).

Milward (2000) further supports the theory that, although language matters, context can sometimes be more influential. Context influences what is being said, as well as when, where, to whom, and how. Thus, in Hall’s framework, context refers to how much (and what kind of) information is required for the receipt and understanding of a message in a given communication situation. Victor (1992) discusses a behavior called contexting, which illustrates “the way in which one communicates and especially the circumstances surrounding that communication” (p. 137). Message senders need to take the culturally normative communication context into account when they formulate a message, and, to varying degrees, message receivers must also interpret the message using unique cues that are obtained from the communication context (Zakaria et al. 2003).

As Peter Ehrenhaus says,

[M]embers of cultures where high-context messages predominate are sensitive to situational features and explanations, and tend to attribute others’ behavior to the context, situation, or other factors external to the individual. Members of cultures in which low-context messages predominate, in contrast, are sensitive to dispositional characteristics and tend to attribute others’ behavior to characteristics internal to the individual (e.g., personality). Individuals use the information that they believe is important when interacting with members of other cultures. (Triandis 1994, p. 127)

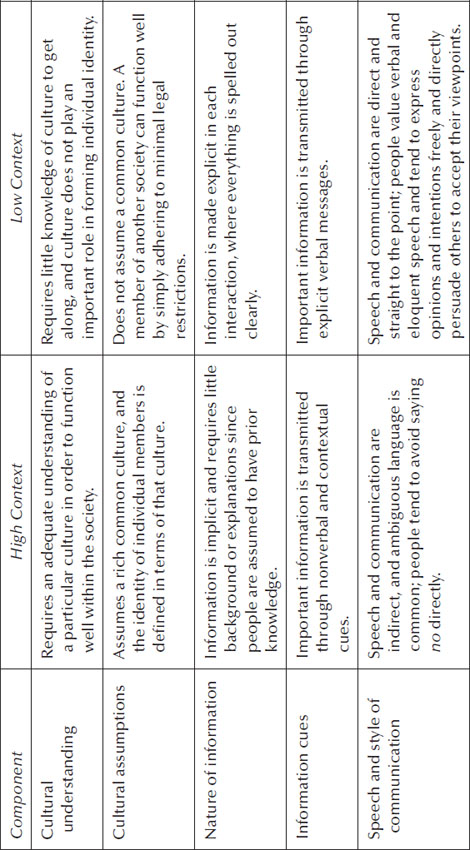

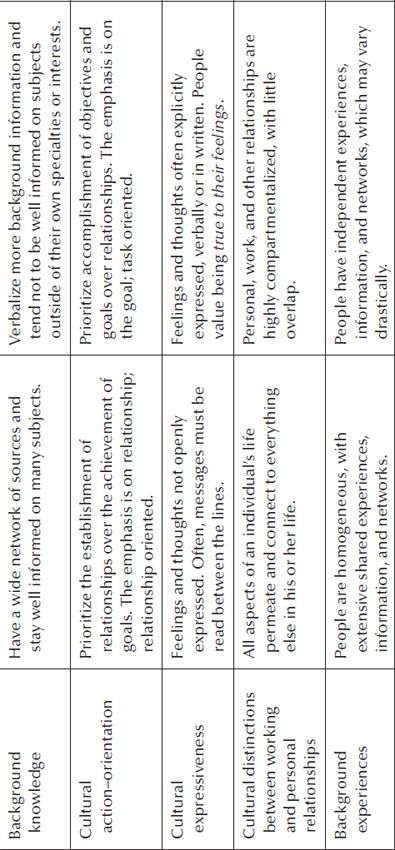

Hall’s contextual dimension helps predict how high-context individuals will internalize the meaning of information based on nonverbal elements—they rely more on the context and less on the content. Low-context individuals, on the other hand, are concerned with the content of the information, such as the explicit words and the message itself, and put less emphasis on the context. Simply put, Hall’s contextual dimension reflects the ways in which individuals perceive, exchange, use, and communicate information. All cultures, whether high or low context, have their own unique identity, language, nonverbal communication cues, material culture, history, and social structures. In essence, Hall views culture as a system for creating, sending, storing, and processing information (Hall & Hall 1990), and his work is summarized in Table 5.1.

Table 5.1 Summary of High- and Low-Context Cultures

Source: Zakaria, N. et al., Information Technology & People, 16, 49–75, 2003.

Ayyash-Abdo, H. 2001. Individualism and collectivism: The case of Lebanon. Social Behaviors and Personality, 29(5), 503–518.

Bloch, B. & Starks, D. 1999. The many facets of English: Intralanguage variation and its implications for international business. Corporate Communications, 4, 80–88.

Cairncross, F. 1997. The Death of Distance: How the Communications Revolution Will Change Our Lives. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Cassell, J. & Tversky, D. 2005. The language of online intercultural community formation. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 10(2), article 2. Retrieved August 23, 2005, available at http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol10/issue2/cassell.html.

Clark, H.H. 1996. Using Language. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Hall, E.T. 1959. Silent Language. Garden City, NJ: Anchor Books/Doubleday.

Hall, E.T. 1976. Beyond Culture. Garden City, NJ: Anchor Books/Doubleday.

Hall, E.T. & Hall, M.R. 1990. Understanding Cultural Differences: Germans, French and Americans. Boston: Intercultural Press, Inc.

Gudykunst, W.B., Matsumoto, Y., Ting-Toomey, S., Nishida, T., Kim, K. & Heyman, S. 1996. The influence of cultural individualism-collectivism, self-construal, and individual values on communication styles across cultures. Human Communication Research, 22(4), 510–543.

Milward, S. 2000. The relationship among Internet exposure, communicator context and rurality. American Communication Journal, 3(3). Retrieved September 20, 2005, available at http://www.acjournal.org/holdings/vol3/Iss3/rogue4/milward.

Pekerti, A.A. & Thomas, D.C. 2003. Communication in intercultural interaction: An empirical investigation of idiocentric and sociocentric communication styles. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 34(2), 139–154.

Uljin, J., O’Hair, D., Weggeman, M., Ledlow, G. & Hall, H.T. 2000. Innovation, corporate strategy, and cultural context: What is the mission for international business communication? The Journal of Business Communication, 37, 293–316.

Triandis, H.C. 1994. Culture and Social Behavior. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Victor, D.A. 1992. International Business Communication. New York: HarperCollins.

Zakaria, N., Stanton, J.M. & Sarkar-Barney, S.T.M. 2003. Designing and implementing culturally-sensitive IT applications: The interaction of culture values and privacy issues in the Middle East. Information Technology & People, 16, 49–75.