CHAPTER 5

STEP #2: FIGURE OUT WHAT TO KEEP

We are not deviating from who we are. We’re building on our values and our foundation.

MIKE ROMAN, CEO, 3M

The biggest part of renovating anything—whether it’s a room, a building, or an entire organization—is understanding what stays and what goes. In each, it’s important not to let sentiment get in the way of progress—a common misstep. That’s a big reason why gathering input from multiple voices is so important; it not only illuminates what the culture is today, but also helps determine the most positive and valued aspects of the company’s historical culture to carry forward.

In our research, 57 percent of organizations that were highly successful in renovating their cultures were very intentional in ensuring that the best of the company’s existing norms were preserved, and fundamental values and history were woven into the new culture.

This practice is especially important for an organization that has a long and storied history. A good example is 3M, a company that has been in business for over a century and has been in the Fortune 500 most of that time. While most know the name well, few understand the company’s roots or even what it really does.

“3M” is based on the company’s original name, Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing. The company was launched in 1902 in Two Harbors, Minnesota, and as the name implies, it was originally involved in mining, specifically digging out corundum—a mineral used for grinding wheel abrasives. Shortly thereafter, the company shifted to manufacturing sandpaper products, and that became the company’s primary business in the early days. Today, 3M is in the Fortune 100, operates in a variety of industries and consumer markets, and produces over 60,000 products under dozens of different brands. Based just outside of St. Paul, Minnesota, the company generates more than $30 billion in sales and has almost 100,000 employees.

The concept of culture renovation could have been written entirely about 3M. The company’s ability to continue to innovate and reinvent itself is legendary, and while much of it is on purpose, some of it has been by chance. As one publication put it, “those three M’s might better stand for Mistake = Magic = Money.”1 Few companies have ever created more useful products seemingly by accident than 3M, an amazing historic record that many attribute to the freedom the company gives employees to make mistakes and its appreciation for innovation.

Remarking on 3M’s admirable consistency and constant renovation, Bill Hewlett, co-founder of Hewlett-Packard, once said: “You never know what they’re going to come up with next. The beauty of it is that they probably don’t know what they’re going to come up with next either.”

15 Percent Time

The five original founders of 3M sound like the start of a bad joke: a lawyer, a doctor, two railroad executives, and a meat market owner. And the irony is, unlike the attitude of 3M today, they had one primary purpose when they established the company: to get rich. But “like so many others who organized mining ventures in the early 1900s,” wrote Virginia Huck in Brand of the Tartan: The 3M Story (1955), “the founders of 3M apparently incorporated first and investigated later.”

As it turns out, the primary product they set out to mine, corundum, was a horrible abrasive. As Huck described in her book, “By the end of 1904, 3M stock had dropped to the all-time low on the barroom exchange—two shares for a shot, and cheap whiskey at that.”

Exhibiting the trait that would eventually become its identity, the company admitted defeat and quickly changed course. The company picked up and moved to Duluth to make sandpaper—but the problems continued. The original sandpaper products were poor, and to add insult to injury, the floor of the new office collapsed shortly after 3M moved in from the weight of the company’s raw materials. But unbeknown to the owners at the time, the move to Duluth introduced to the company a fortuitous new hire who would eventually establish 3M as the powerhouse it is today.

In 1907, William McKnight, a 20-year-old assistant bookkeeper, joined 3M. Wrote Huck: “His assets were a most brief business school training [five months], inherent determination, and high ambition. No one who saw the quiet, serious boy apply for the job could have possibly predicted that in a very short time he would become the major influence in the success of 3M.”

While McKnight reportedly was soft-spoken, he also was direct and efficient. By 1911, he had worked his way up to sales manager. He was known for going into the back room with a client’s workmen to personally demonstrate 3M products . . . and at the same time to hear their complaints. As a result, he quickly became aware that 3M’s sandpaper was an inferior product. McKnight suggested to management that communication between sales and production needed to improve—and management agreed. They made him general manager in 1914 to fix the problems he was witnessing. Early into his new job, he witnessed another problem: several shipments were ruined by an olive oil leak and went unnoticed by anyone at the company until customers complained. McKnight quickly established a research lab to test materials at every stage of production, creating the company’s first quality control mechanism—the first of many creations during McKnight’s tenure.

In fact, it was under McKnight that 3M’s famous “15 percent time” began. For many decades, 3M has urged its employees to devote 15 percent of their time on the job to doing something beyond their usual responsibilities—such as experimenting with new technology or collaborating with others outside their work areas on new ideas and projects. Some of 3M’s most famous products were the direct result of this policy, including Post-it Notes, Scotch Tape, a wireless electronic stethoscope, and many more.

Other companies have popularized this concept, most notably Google’s 20 percent time, which is credited with creating Gmail and Google Earth among other products. But it was McKnight’s philosophy of “listen to anybody with an idea” that was the original basis for what became 3M’s 15 percent rule.2 It all began in 1920 when McKnight received a letter requesting bulk mineral samples, and McKnight asked the originator of the letter, a Philadelphia inventor named Francis Okie, what he intended to do with the minerals. Okie said he wanted to develop waterproof sandpaper. Realizing that this would be a valuable product, McKnight bought the rights to the idea and hired Okie. By 1921, 3M had released one of its first successful sandpaper products, Wetordry. As Richard Carlton, 3M’s director of manufacturing and author of its first testing manual, wrote, “Every idea should have a chance to prove its worth, and this is true for two reasons: (1) If it is good, we want it; (2) If it is not good, we will have purchased peace of mind when we have proved it impractical.”3

It was Wetordry, and the concept of pursuing ideas, that spawned one of 3M’s most successful products.

In 1923, a mechanic at a St. Paul auto body shop was having trouble painting a two-tone car because tapes at the time were poor at masking sections of the car; they left residues and generally didn’t work properly. A 3M engineer named Richard Drew, who was testing Wetordry at the shop, stumbled upon the scene and resolved to address the problem. Drew spent the next two years thinking about and experimenting with masking tape before he finally found the right combination of adhesive and backing paper. The tape, which was nicknamed Scotch masking tape, ultimately became one of the most well-known brands ever. It was a hit right off the bat, with first-year sales of $164,279 and rising a decade later to $1.15 million.4

Soon after, Drew created an even bigger seller for 3M: cellophane tape. He witnessed a co-worker wrapping his masking tape invention in cellophane and realized if the adhesive were on the cellophane itself it would be moisture-proof. Thus, the Scotch tape we know today was born.

Encouraged by these discoveries, McKnight implored his managers: “Encourage experimental doodling. If you put fences around people, you get sheep. Give people the room they need.”

To further ingrain a culture that encourages innovation and experimentation, McKnight developed what became known as the McKnight Principles in 1948—words of wisdom that today are sacred in 3M’s corporate culture. The most famous passage celebrates pushing decision making lower in the organization (a key tenet of organizational agility) and celebrates initiative and the importance of making mistakes. He wrote:

As our business grows, it becomes increasingly necessary to delegate responsibility and to encourage men and women to exercise their initiative. This requires considerable tolerance. Those men and women, to whom we delegate authority and responsibility, if they are good people, are going to want to do their jobs in their own way. Mistakes will be made. But if a person is essentially right, the mistakes he or she makes are not as serious in the long run as the mistakes management will make if it undertakes to tell those in authority exactly how they must do their jobs. Management that is destructively critical when mistakes are made kills initiative. And it’s essential that we have many people with initiative if we are to continue to grow.5

Even in those early days, culture translated into performance. When McKnight became general manager in 1914, 3M was a $264,000 company; by the time he retired as chairman in 1966, 3M had grown into a $1.15 billion company. More important, management continued to follow McKnight’s principles, and 3M kept growing for the next several decades. 3M developed many more famous inventions, expanded globally, broadened its product lines, and was widely admired.

A Commitment to Renovation

Despite its success, in the 1990s, 3M suffered the same ailment many other prosperous companies have run into: it became complacent. The Los Angeles Times reported in 1995 that “For decades management books have called 3M a model. Yet the glow of such compliments may have distracted the company, because in this decade 3M allowed old, less profitable products to drag down its earnings growth and stock price.”6 Some called the company “fat and happy.”

In true 3M fashion, the company’s leaders decided it was time to renovate. In December 2000 they brought on General Electric veteran James McNerney as CEO, the first outsider to run the company in its history. Early in his tenure, McNerney wisely pointed out: “I think we’re world-class at the front end of the [innovation] process. If I dampen our enthusiasm for that, I’ve really screwed it up.” McNerney made innovation a core tenent of his leadership, and the market cap improved almost a third during his tenure.

Today, 3M is run by Mike Roman, a veteran of more than 30 years with the company, who was named CEO in 2018. I met with Roman and explored what culture renovation means to him and the company.

“The world’s changing around us. If you’re not leading change, you’re falling behind,” Roman told me from his Minnesota home. “That’s not something CEOs don’t know, but that’s a good reminder. That’s true for strategy and your competitive value proposition, but it’s also true about culture.”

Although 3M has an enviable record of long-term success, the mindset of continuous improvement runs deep in the organization. When Roman was named CEO, he wanted to carry on that mantra, and he approached it by renovating what had made 3M great to begin with.

“3M always had this idea of getting better, doing better for our customers, and that brought our culture forward as much as anything the last decade,” says Roman. “We’ve stepped up in a number of strategic areas that are critical to really maintaining the 3M value model, as I call it. It’s served us well for 117 years. We built a big business. We’ve solved problems for customers. We’ve created a tremendous capability and culture as a result of that.

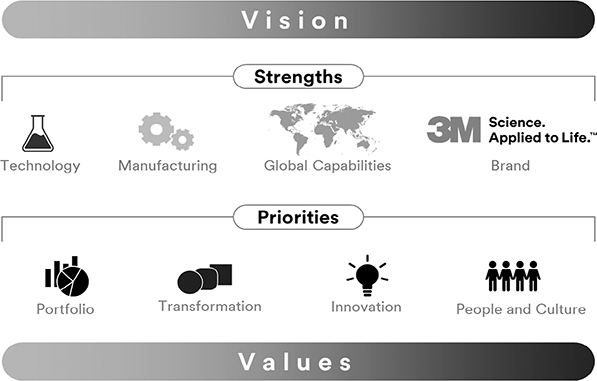

“We didn’t launch a new cultural initiative with consultants or with a small team. We went out and engaged our employees broadly with multiple collaboration tools, listening, post-engagement steps,” Roman continued. “We are not deviating from who we are. We’re building on our values and our foundation, and we have some fundamental strengths that are really core to who we are. [See Figure 5.1.] Our technology, our manufacturing prowess and capabilities, our global ability to manage multiple business models elsewhere in many markets, and a brand that means so much to us. But that alone doesn’t move it forward.

FIGURE 5.1 3M’s Strengths and Priorities

“We have four priorities. The first priority is managing our portfolio businesses. They are not permanent. We invented masking tape in 1925. We still are a leader in masking tape. Doesn’t mean it should be the highest-priority organic investment in our business. We have other areas that are more leading edge. And so we have to think about our portfolio. Sometimes it means making acquisitions, sometimes divestitures.

“The second is we have to transform our company digitally. And this has been a big investment for us. Changing, deploying a new ERP ecosystem, digital tools, automating, bringing in new capabilities. You have to do that to be competitive.

“And then you have to continue to advance innovation. We have to look at how do we stay ahead of competition? How do we solve customers’ problems in a fast-changing world of technology? How do we add to our technology capability? So that’s kind of the fundamentals of the 3M value model. And as we move further in those leading changes in those areas, it became very clear that people and culture was fundamental to everything we were doing. None of that is successful without putting a foundation of a successful culture underneath everything we do.”

Roman was fortunate that he stepped into his role on the same day Kristen Ludgate was named chief human resource officer (CHRO). Ludgate had been with the company for almost a decade in various legal, communications, and HR roles. She became an important partner to Roman as they began to renovate culture.

“Kristen and I decided early on as we stepped into our roles that we had to emphasize this, and we had to think of culture just like any other strategic priority,” Roman said. “We don’t win if our culture doesn’t support all those fundamental strengths and priorities, so it became one of our fundamental four priorities that we think about in strategy.”

“For 3M, whenever we needed to recharge the business, we’ve looked at culture as a tool that goes back decades and decades,” said Ludgate. “So, we’re all very excited that other companies now think culture is the thing to do. But that’s something that we would naturally turn to as an organization. We were in a position of strength, but we also knew we could not sit still. You don’t want to wait until you see signs of weakness in your culture to try and change or improve it, especially given the speed of business and how central culture has always been to 3M’s success.”

“I love your term ‘renovation’; I think it’s a really nice way to think about it—what renovation is needed. We asked ourselves, how do you intentionally renovate your culture?” said Ludgate. “We knew we had to have a plan to articulate what our aspirational culture is, and then do the hard work of rewiring. But if you want to articulate what it is, you can’t have this tiny little group sitting in St. Paul, Minnesota, when two-thirds of your business is outside of the United States. There’s a real risk you start on a culture project and you don’t actually create anything that’s relevant for the majority of your people. I think the only solution to that is the ongoing listening.”

Like T-Mobile and others, 3M employed a listening strategy to ensure management didn’t assume it knew all aspects of the culture. It sought input from everyone throughout the organization, from the leadership team right on down to production workers.

“We engaged the top leadership team, we engaged our board, we tapped 3Mers from all over the world to sit on focus groups and advisory panels, and we established a cross-functional core team,” said Ludgate. “We then took some early thinking out into the organization through crowdsourcing. We’ve been amazed at the level of response—we received 21,000 ideas from employees in every region about what they loved, what they needed more of, and their ideas for how to advance our culture. That deep listening has been really important. And, of course, deep listening is itself a way to announce a change of culture.”

To ensure it didn’t do this in an insular way, 3M’s leaders looked at other companies for benchmarks. They didn’t have to look too far, as it turned out. Amy Hood, chief financial officer of Microsoft, had been on 3M’s board since 2017.

“When we activated our culture project, we asked, who do we want to talk to and benchmark with? And there was Amy and Microsoft right there,” Roman recalled. “They were at the leading edge, and so we engaged with them. One of the things that we learned early was the importance of activating culture first, not redesigning or innovation, but get a focus on culture. And it served us well. If you look at our cultural elements, they aren’t the same as Microsoft, but they resonate similar. I think Microsoft, if anything, got us excited about what we were intuitively thinking we wanted to do.”

In addition to benchmarking with others, the principles that William McKnight originally laid out are followed to this day by Ludgate, Roman, and other 3M executives.

“It’s the idea that we can try something, and if it’s not perfect, we’ll make it a little better tomorrow. We need to work on our culture that way,” Ludgate says. “We’re a science company. The experience of hypothesizing, iterating, learning, and improving—we need to be willing to do that with the processes, policies, and practices that support our culture. We think of this as wiring our culture into our organization, and it’s an ongoing evolution.”