Chapter 2

The Customer Success Strategy: The New Organization versus the Traditional Business Model

Why Does Customer Success Matter?

Before we dig into the organizational aspects of customer success, let's talk about the desired outcomes that drive the accompanying investment. This is important because the way you organize for customer success will often be driven by your primary motivations for investing in it. There are three basic benefits that come from executing customer success well:

- Reduce/manage churn.

- Drive increased contract value for existing customers.

- Improve the customer experience and customer satisfaction.

Reduce/manage churn. As we explored in Chapter 1, using the early days of Salesforce as an example, churn can be the killer of a recurring revenue business. If churn is too high, one solution is to invest in customer success. It's important to understand that investing in customer success cannot make up for fundamental flaws in other parts of the enterprise. If your product is not good enough or your implementation processes do not meet customer requirements or your sales team is continually setting improper expectations, you will fail regardless of the quality of your customer success efforts. All things being competitively equal, an investment in the people, processes, and technology for delivering customer success will result in a reduction in churn if it's too high or a management of churn if it's at or near an acceptable and sustainable level. The specific financial benefits will depend on the size of your installed base.

The negative impact of churn goes beyond financial results, too. Companies always consist of people, so when companies churn, people are affected. Those people know other people, and negative publicity can spread quickly. If your product touched, or was used by, lots of people, the negative impact can be viral. There's also a very good chance that a customer who churns from you buys from your competitor. This means you get dinged twice. It's like losing a game in a pennant race to the team you are chasing—you lose one and they win one. It's a double-whammy and very painful in a competitive market, exacerbated further when that ex-customer becomes a reference for your competitor (which they will do anything and everything to make happen). These are negative second-order effects. We'll talk about positive second-order effects in a minute.

Drive increased contract value for existing customers. This is usually referred to as upsell and cross-sell, but those terms don't always mean the same thing to everyone, so I avoid them when I can. Simply, it means selling more stuff (recurring revenue stuff) to your existing customers. Some companies don't have a churn problem because their products are inherently sticky or because the expense and effort of implementing them is significantly large. Workday would be an example of the latter situation. Very few of its customers have ever churned. But that doesn't mean customer success is unnecessary or unimportant. Workday invests significantly in customer success to ensure against the possibility of churn, but, more specifically, to deliver additional bookings/revenue to the company bottom line from the installed base. Consider a company whose average customer increases its spend or contract value by 30 percent annually. That's an extremely positive metric, but it leads to an interesting view of the customer who expands by only 10 percent. There's no churn. In fact, the net retention number for that customer is 110 percent. Many companies would kill for that average. However, for this company and that customer, significant revenue is being left on the table as compared with the average. Because it's been proved that average customers (not just great ones) are growing at 30 percent, it's reasonable to assume that applying customer success to those below-average customers will bring them up closer to the average. In situations like this, you basically want to treat that 20 percent deficit as if it is churn and aggressively seek to remedy it. If your existing base of customers is sufficiently large, moving the overall net retention from 130 to 137 percent will have a significant bottom line impact. Pushing those 110 percent customers closer to 130 percent will have that exact impact and might easily justify an increased customer success investment. It's also important to understand that the additional revenue delivered in this example will come much less expensively than new customer acquisition because there's no associated marketing expense and almost certainly less sales expense, too.

Improve the customer experience and customer satisfaction. Adam Miller is the CEO of Cornerstone OnDemand, an extremely successful recurring revenue company. He told me recently that he does not try to justify his significant investment in customer success financially. He believes so passionately in delivering on the company's value promise to its customers—and customer success is his vehicle for doing so—that he simply builds the cost of that team into his gross margin model and then manages to it. Financial results almost certainly accrue to Cornerstone from its customer success investment, but it's not the driving reason for doing so.

There's also something commonly referred to as second-order revenue that results from keeping and delighting customers. Most companies are not measuring and accounting for this in their financial models; it simply shows up as additional sales. But it's the direct result of customer success. Jason Lemkin, ex-CEO of Adobe Echosign, coined the phrase second-order revenue and attributes an increase of as much as 50 to 100 percent of the LTV of a customer to it. The theory is simple and logical:

- John loves your product and leaves Company A to join Company B and buys your product again at Company B.

- John loves your product and tells three friends about it and some of them end up buying your product, too.

Those two situations are actually quite measurable, and you should strive to do so. But there are a number of other positive effects of creating attitudinal loyalty—references, positive reviews, word-of-mouth, and so on. Real customer delight can be viral, too.

Customer Success Is a Fundamental Organizational Change

As mentioned in Chapter 1, real organizational change at the highest level in an enterprise is actually pretty rare. Although reorganizations are a way of life for most businesspeople, the fundamental org structure of a business has not changed much over the years:

- Somebody designs the product.

- Somebody builds the product.

- Somebody creates demand for the product.

- Somebody sells the product.

- Somebody installs/fixes the product.

- Somebody counts the money.

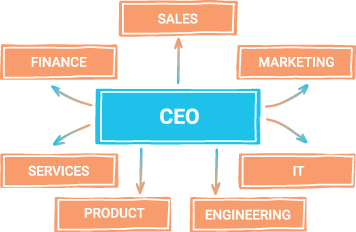

In the past 40 years, there has been only one major change to that standard organization model—the addition of IT. No business operates today without a deep dependence on technology, and that dependency necessitated the creation of an organization to manage that technology. This means that most companies today have a high-level org chart that looks like the one below (see Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1 High-Level Organizational Chart

For all the reasons we've already explored in Chapter 1, customer success has now entered the landscape. It's not just a new title given to someone taking a different angle on an old job. That happens all the time. But new organizations are different. They form only when some critical set of drivers come together, and usually one or more of those drivers is an external force affecting many or all companies. The formation of IT orgs to support the burgeoning technology explosion is a perfect example. It's happening now with customer success, too. Three key drivers must be present:

- The business is dependent on it.

- It requires a new set of skills to execute.

- The activities and related metrics are new.

Business dependency. We spent all of Chapter 1 outlining how businesses have evolved to the point at which customer success is critical to the business. When you rely on customer LTV, not just a one-time sales event, to deliver long-term business success, it changes everything. People, technology, investment, and focus come to that part of the business, and one of the results is the formation of a new organization.

New skills. As with IT, customer success requires a new set of skills. You can't just take a smart engineer, make her a CIO, and expect her to manage all the technology in a company and understand the required processes, security, and administration to deliver the requisite business value. It's obviously not that simple. The same is true for customer success. If the business need for managing customer health does not exist, there's probably no one at your company who is analyzing the available data to determine which customers are healthy and which are not. There's also no one driving proactive outreach to customers who appear to need assistance or who have opportunities for growth. There may not even be anyone who knows how to measure churn, retention, customer growth, or customer satisfaction or which of those to even care about. The capabilities for doing this certainly exist, but they need to be turned into specific skills.

Activities and metrics. A big part of defining a new organization has to include defining what it will do and how it will be measured. Customer success certainly comes with the need for both. Someone has to decide what the key metrics are by which success will be determined:

- Gross renewals

- Net retention

- Adoption

- Customer health

- Churn

- Upsell

- Downsell

- Net Promoter Score (NPS)

And then the activities that will drive those metrics:

- Health checks

- Quarterly Business Reviews (QBRs)

- Proactive outreach

- Education/training

- Health scoring

- Risk assessment

- Risk mitigation processes

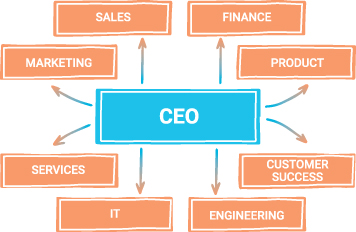

Some of those activities have been done in the past in critical situations and as one-offs, but, outside of a few mature SaaS companies, they have not been brought together and organized under one responsibility and with clear success metrics (see Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2 Expanded High-Level Organizational Chart

Of course, it's not enough to just create a new box on an org chart even if you fill it with really smart people and give them the metrics by which they'll be measured and suggested activities for driving success. No organization stands alone, so let's discuss the keys to making this new organization work across the entire enterprise.

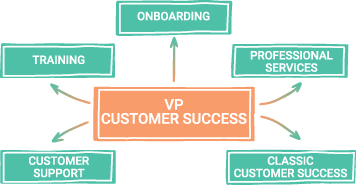

Let's start by getting on the same page with regard to terminology. Customer success is the term we're using in this book because it's the buzz phrase that's caught on in the industry. But it's not the only term used to describe some kind of renewed focus on customers. There's not even consistency from one company to the next regarding what customer success means. As we mentioned in Chapter 1, customer success is a philosophy as well as a specific organization. As a philosophy, it often leads to an organization that looks like Figure 2.3.

Figure 2.3 Organizing around Customer Success as a Philosophy

You can see in this example that customer success is the umbrella phrase used to describe the entire post-sales world. It's a catchy, meaningful term because the goal for most companies really is to help make customers successful. Using it to describe the whole organization pushes that value front and center and sets the right expectations for both customers and employees. It's the kind of idea that CEOs and boards can get behind as they seek to become, or at least to be perceived as, more customer-centric.

You probably also noticed the box within the customer success organization labeled Classic Customer Success. I use that phrase to distinguish the philosophy of customer success from the part of the organization made up of people with that title who are actually the feet on the ground doing the hard work to drive success for their customers. I use the word classic because the original use of the term customer success at Salesforce, and many others after them, was to describe a very specific job and the department that was made up of people doing that job.

What Customer Success Is Not

As I mentioned, there are a number of other terms used to describe organizations or efforts within an enterprise that also bring more focus on the customer and are designed to improve the customer's experience and the value they get from their vendors. In most cases, these are not the same as customer success but may overlap in some areas, so it's important to understand them if you are going to understand customer success. Because of the buzz around customer success, the visibility of these organizations or efforts has also been raised, which has created some confusion in the market.

Customer experience (CX): CX typically refers to the assessment and management of the overall customer experience across a customer's lifetime. This includes understanding and managing the customer's experience at every touchpoint with the vendor from sales to onboarding to invoicing to customer support to renewals and is usually driven or measured by survey results. Many companies, such as Satmetrix, have successfully built their entire business around CX. It's a discipline that includes technology solutions, best practices, and conferences. Because customer satisfaction surveys are often part of measuring overall customer health, there is a tiny bit of overlap between customer success and customer experience.

Customer relationship management (CRM): CRM is widely used to describe the market space for solutions such as Salesforce.com, Microsoft Dynamics, Oracle CRM (Siebel Systems), and so on. In fact, Salesforce's stock market ticker symbol is CRM. It's a term primarily used to describe the market, not a specific role or discipline, but, because it's so ubiquitous, it is often viewed as subsuming customer success or that customer success is simply an offshoot of CRM. Customer success management could very accurately be called CRM if that term was not already in use to describe something very different. But in today's landscape, they are most certainly not one and the same.

Customer advocacy: Customer advocacy is used most often to describe the critical role that happy and successful customers can play in advancing a vendor's agenda with references, case studies, positive reviews, and user group participation. Industry, science, and technology solutions such as Influitive are being built around the idea of customer advocacy, and it is parallel and complementary to customer success. If customer success can be defined as managing customer health, then customer advocacy is a source of health-related data to assess one aspect of customer health. Customer advocacy may also be the output of those customers who have high health scores. You can see that customer success and customer advocacy might easily form a virtuous cycle.

Customer Success Is NOT Customer Support

There's one other critical organizational distinction that we should spend a few minutes discussing as it pertains to customer success and that is customer support. Customer support is an organization and discipline that has been around for a long time. The description of what customer support does almost always centers on the phrase break/fix. This is the 800-number, chat window, or e-mail address you use to get help with something that appears to be broken or not working as you expected. This touchpoint is critical to a customer's overall experience with a vendor. How many times have you heard someone complain about the long wait on hold or the unhelpful person they finally talked to? For many of us as customers, especially consumers, this is the primary point of contact with our vendors. That's one of the reasons that CX folks focus a lot of attention here. It's also a source of tremendous confusion when it comes to discussing customer success for a number of reasons.

One reason is that they sound similar, not just the words and the acronym CS but the perceived meaning. Isn't customer success just the new-age way of saying customer support? The answer is no, but that conclusion is an easy one to come to.

There's also usually an overlap in skills. Customer support people are expected to be product experts, as are Customer Success Managers. Both roles require good customer-facing skills (personality, patience, true desire to help, thick skin, etc.). Problem solving is also a useful talent in both roles.

Another source of confusion is simply naive logic, which usually goes like this: “If we have a team of people who know our product and help our customers when they need it, why do we need a second team of people with those same skills basically doing the same thing?”

To create a successful customer success organization requires that the lines of responsibility between them and customer support be drawn very clearly. There are several criteria that can help distinguish the two groups:

| Customer Success | Customer Support | |

| Financial | Revenue-driver | Cost center |

| Action | Proactive | Reactive |

| Metrics | Success-oriented | Efficiency-oriented |

| Model | Analytics-focused | People-intensive |

| Goal | Predictive | Responsive |

The two teams are not variations on a common theme and are actually paradoxical in many of the most important ways.

Too often, because of the similarities, customer success is initially formed inside the support organization. For all of the clear distinctions listed previously, this does not typically lead to success. What usually happens is that customer success becomes a type of premium support offering. Enhanced support offerings are a very good thing, but they aren't customer success. They typically offer positive elements for customers such as improved service-level agreements (SLAs), extended hours of support, multigeography support, designated points-of-contact, direct access to Level 2 support, and so forth. These are all very good things for which customers should, and do, pay extra, but they are still not customer success. They are primarily reactive to incoming customer problems and will ultimately be driven by efficiency (number of cases closed/day/rep). In contrast, customer success uses data to proactively predict and avoid customer challenges and will usually be measured by retention rates.

Both organizations are 100 percent needed to be effective as a company. The admonition here is simply to be mindful that they are not designed to accomplish the same goals and that organizational separation is actually far better than organizational proximity. Ultimately, the two teams will work closely together and actively collaborate on many customer situations, but the separation is required, at least initially, to formalize the discipline and processes around customer success without the influence of the reactive customer support team.

What Customer Success Is

Now that I hope we've cleared up some potential confusion, it's time to go beyond the simple org structure and talk about how to make a customer success–centric enterprise really work. A good place to start might be to elaborate on the criteria mentioned earlier that differentiate success from support. This might also help you understand the kind of person you will need to lead the organization and the characteristics of those filling the individual contributor roles as well.

Customer success is:

-

A revenue driver—Managing the installed base at a recurring revenue business means being responsible for a significant portion of the financial well-being of the company. Customer success is an organization that drives revenue in two ways.

- 1. Renewals (or avoidance of churn)—The renewal is a sales transaction whether it is explicit (signing a contract) or implicit (auto-renewal or non-opt out). As consumers, we live in this world with our cell-phone providers. Opting out at any given time is an option available to us. If we're under a two-year contract, there might be a penalty, but it's still an option. If we are not under any kind of contract, then we can opt out at any time without penalty. In either case, there is an implied sale that happens every month we don't change providers. The team responsible for ensuring that we don't opt out is what we're generally referring to as customer success in this book and what many B2B companies literally call customer success. Consumer companies such as AT&T or Verizon may not call it customer success, but there are certainly teams that analyze the data and try to avoid or mitigate the risks they identify in any given customer or group of customers.

- 2. Upsells—This is the act of buying more product from your vendor. To extend our cell-phone analogy, this happens when you buy a more expensive package, such as unlimited international calling or unlimited text messaging or more data. Those are upsells that increase the value of your contract to your provider. The same thing happens in the B2B world.

In many cases, the customer success team may not actually execute on the sales transaction, whether it's a renewal or an upsell. There are often specific sales teams for contract negotiations and for final signatures. But, even if the sales transactions are not executed by customer success, they are enabled by them. To repeat something we've said before, successful customers do two things: (1) remain customers (renewing their contract or not opting out) and (2) buy more stuff from you. Because the job of customer success is to make sure customers are deriving success from your product, they are a revenue-driving organization. This means they need to be people who are at least sales-savvy, if not having direct sales experience.

- Proactive—This is a major difference from customer support in which most individuals react to incoming customer requests, whether they are phone calls, chat requests, e-mails, or tweets. Customer success teams use data and analytics to determine which customers should be acted on, either because they appear to be at risk or because there appears to be an upsell opportunity or because there's a regularly scheduled event such as a QBR. Beware of bringing into customer success those who have spent their lives being reactive. The transition is doable but is a tough one.

- Success oriented—Success metrics drive top-line (bookings or revenue) financial gains for your company. New business sales is clearly a success metric. In the customer success world, the key metrics are often renewal rates, upsell percentages, overall growth of your customer base, and so forth. Efficiency metrics are very different from these. They are focused on reducing costs as opposed to increasing revenue. Cutting the assembly time for a new car by one day is an efficiency metric. If you build a lot of cars, this is tremendously valuable to the company but does not directly result in the sale of more cars. People who are efficiency experts are not necessarily the same people who will successfully drive more revenue or bookings.

- Analytics-focused—Most businesses and organizations are driven by analytics, but customer success is driven by forward-looking, or predictive, analytics in a way that many others are not. The sales analogy here is to analytics that help you identify the best opportunities in your pipeline upon which to act. Analytics similarly drive customer success by predicting outcomes such as churn or upsell, allowing the optimization of the time spent by the team. Time spent by an expert with a happy customer will usually yield good things, such as higher customer satisfaction scores and more references. But that may not be as valuable as time spent with a struggling customer that ensures their retention. Being analytics-focused with the right kind of predictive data is critical to driving an effective customer success team.

- Predictive—This needs to be the customer success focus, not only of the analytics and actual analysis but also of the people. Remember the contrasting position is simply responsiveness. It's a great thing to improve your responsiveness, especially when it comes to customers. They appreciate it, and it makes for a better overall experience for both parties. But predictability takes this one step further—figuring out who to talk to before they need to call you.

Customer Success's Cross-Functional Impact

In creating good overall organizational health with the insertion of this new team, the first thing that needs to be recognized is that customer success is not a philosophy isolated to the organization by the same name. It must become an idea that permeates the entire company and culture. Perhaps more than any other organization, customer success is not an island. Regardless of whether you run a recurring revenue business, if you are truly committed to the success of your customers as a primary pillar of your business, every part of your company must be equally committed to it and incented by it.

Let's consider incentives for a moment. One way to ensure that all parts of your company are truly committed to customer success is to apply appropriate incentives. Most companies have an executive bonus plan, and many also have a bonus plan that goes down to most, if not all, employees. In both cases, the bonus is probably tied to overall company success. That means someone, probably your CEO with board approval, decides what the right measures of company success are and what the appropriate payouts are, too. At some companies, it might be just based on sales growth. At others, it could be profitability. At a customer success–driven company, it will include some kind of retention metric, too. A simple, but extremely effectively plan might have only two elements—top-line revenue/bookings growth (sales) and retention. If every employee, but especially the executives, were equally incented to be thinking about retention and sales, that sends a very strong statement that the company prioritizes both, and has a high likelihood of accomplishing what compensation/bonus plans are usually designed to do—change behavior.

Another related idea here is to ensure that one person is the owner of the customer success metric, which might be a renewal rate, a net retention rate, or a customer satisfaction score. Whatever the measure, one person needs to own it. There's an old business saying that's very true: “If many people own something, no one owns it.” You wouldn't think of running a business and not having one person responsible for the sales number, right? If you are committing to customer success as an equivalent pillar (to sales) in the long-term success of your company, don't you need to do the same thing with your retention number? Most definitely. Assign it to someone and give her the same authority that you give to your sales vice president (VP) to make his number. The authority to shake trees, push on other organizations, fight for resources, make strategic business decisions, or all of the above. Someone needs to own it and know that his job depends on making his number. One could easily argue that the primary job of the leader of your customer success efforts is to ensure that all other organizations are consistently thinking about retention.

These two ideas come together to drive a healthy business forward in the following way. Joe is the VP of sales at Acme. Acme has been around for a while and is a healthy, growing business. He has 45 quota-carrying sales reps, 15 solution consultants, and 5 more staff to run the order desk, administer the tools they use, and generally support the team. He also carries a $73 million bookings quota for this year. Joe obviously reports to the CEO.

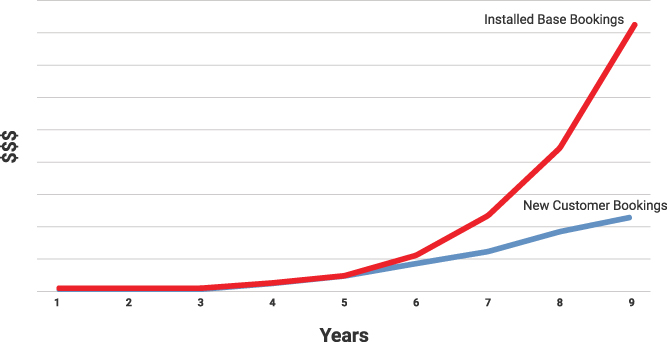

On the other side of the office is Sherrie. Sherrie is the VP of customer success. She has 29 CSMs, 7 renewal and upsell reps, and 3 people in customer success operations supporting her and the team. She's responsible for managing all 2,200 Acme customers. She carries a $145 million bookings quota for this year. That's $132 million of renewals and a 10 percent upsell target for an overall net retention goal of 110 percent. She also reports directly to the CEO.

One thing I'm sure you noticed is that Sherrie's number is larger than the VP of sales. Significantly larger. This happens in a recurring revenue business, and it often does not take long—four to five years for a healthy, growing company and shorter if the top-line starts to flatten. Consider a company that started three years ago and did $1 million, $4 million, and $10 million of bookings in those three years. Let's also say that net retention has been 100 percent so far, meaning the current value of the installed base (ARR) is $15 million. Now let's assume that the growth target for sales for the coming year is 50 percent. This is a nice, not-uncommon company story and a reasonably aggressive growth strategy. It also means that whoever owns retention, assuming net retention will be 110 percent going forward, will have a bigger target than the VP of sales: $16.5 million versus $15 million in the coming year. That difference will grow quickly over time. If both hit their number this year and the same growth targets exist the following year, the numbers will be $34.7 million and $22.5 million, respectively. See Figure 2.4 for how their respective quotas will look over several years.

Figure 2.4 Installed Base versus New Customer Bookings

Back to our story. On a Monday morning Joe walks into the office of the VP of engineering, which he does several times a week. The conversation likely centers around the things Joe needs from Bill to make his number this year.

“The competition is killing us on a couple of missing features, and an integration with WhatBit would give us a competitive advantage I could sell the heck out of. Plus, I need a little hack on our demo, probably no more than two to three days of work, to make it really rock.” Parting words may go like this, “If we can't get these things done, we'll have a really tough time making our sales number, and we'll all get killed as stockholders.”

This kind of conversation happens all the time and has for years.

Later that same day, Sherrie also walks into Bill's office. The ensuing conversation actually sounds pretty similar but, of course, with Sherrie's twist on it.

“Overall performance is really hurting us right now. A couple of key customers are putting some pressure on their renewal as a result. Also, there's a report that I know looks ugly in a demo, but our customers are screaming for it. One other thing—the Blart feature is really cool, but I need it to stand alone so we can sell it as an upgrade, not part of the standard package. If we can make these things happen, I think I have a shot at my number, and we'll all be happier stockholders.”

The problem is clear, right? These requests compete with each other. Both are good for the business; nevertheless, there's tension as a result. Tension is nothing new in a business. Organizational tension, if managed properly, is the engine that drives a company forward. The previous scenario is why you want Bill, the VP of engineering, to be both incented and influenced equally by his conversations with Joe and Sherrie. As the CEO, you need to create this reality. Joe and Sherrie each own a number that's critical to your business. You want them to have equal authority around the company to make their number so the business will thrive. You also want Bill to be incented to deliver for both of them. Sherrie's conversation needs to have the same weight with Bill as Joe's conversation does. This is a power shift at most companies. Sales is king, and has been forever, and rightly so. When top-line growth is the only thing that really matters, the person driving those results has the power. But when you turn your focus as a company toward customer success, especially if you are a recurring revenue business, some of that power will move to the person who owns retention. Over time, as your installed base becomes far more valuable than new business bookings, the power shift will continue accordingly.

Impact on Sales

Now, let's take a closer look at each of the major organizational groups within an enterprise and how a customer success focus will change how they operate. Because we've already started down this path, let's start with sales.

I'm actually going to lump sales and marketing together here as their joint goal is the same. I'll narrow marketing down, for the purposes of this discussion, to demand generation—the people and processes that feed leads to the sales team to drive new customer acquisition. How does this world change if the company is newly focused on customer success and retention? Several things will happen either immediately or over time:

- A new focus on marketing and selling only to customers who can be successful long-term with your product

- Less emphasis on maximizing the initial deal, especially if it's at the expense of LTV

- Overall awareness of renewals

- Improved expectation-setting with prospects

- Much more attention paid to knowledge-transfer and post-sales prep to ensure onboarding and ongoing success for the customer

- Incentives around renewals and/or LTV

These are significant and fundamental shifts in the thinking of your acquisition team. Similar to CEOs, as discussed in Chapter 1, sales reps really do want customers to have long-term success. Most are not out to simply make their money at the expense of the rest of the company. But again, their incentives and a history of short-term thinking often get in the way. For your company to have long-term success, the way you think about demand generation and sales and perhaps how they are incented may need to dramatically change.

At the extreme, you may even end up giving veto power over sales deals to the person who owns retention. This sounds like a dangerous proposition, and it is. But it might be the right thing to do if the power is wielded very carefully and driven by real data, not just anecdotes and instincts. Ultimately, if this authority is not given to your VP of customer success or to the chief customer officer, it resides in your lap as the CEO and the one who has to balance the need to make this quarter's number with the pain of selling to the wrong customer and possibly even losing that customer in the long run.

Over time, and with the accumulation and analysis of lots of data, these decisions should be information-driven, even to the point of refocusing your demand generation team on only those prospects who have a high likelihood of a lifetime of success.

Impact on Product

Now, let's talk about your product team. I'm encompassing both product management and engineering/development/manufacturing in this discussion. We've already examined one example in our story of Joe, Sherrie, and Bill. Because customers are no longer held captive by the enormity of the upfront investment and the cost of change, your product thinking must also shift toward retention, not just sales. To put it simply, your product must deliver to customers just as much as it appeals to prospects. In fact, one definition of customer success that I've heard is delivering on the sales promise. Remember that the shift here is not only about caring about customers but also about knowing that their LTV is life or death for your company. Retention thinking in your product team might look like this:

- Building return on investment (ROI) measurements into your product

- Making your product easier to implement

- Designing for ease of adoption, not just functionality

- Stickiness is more important than features

- Performance is more valuable than demo quality

- Creating modules that can be upsold rather than integrating all features into the base package

- Making customer self-sufficiency easier to attain

Many of those characteristics are part of the natural thinking of a great product team already, but customer success–centric companies will make them imperatives, not nice-to-haves.

The good news is that, in a properly organized, customer-focused business, the person who owns retention or customer satisfaction will constantly drive these imperatives. No one needs to remind everyone at a company how important it is to be able to sell your product to new customers. But it's new thinking to bring retention and LTV into the same focus for much of the company. Not so for your VP of customer success who will have this in her DNA. No one will need to remind her how important customers are. Her paycheck and job will be riding on it, and she will, if she's doing her job well, consistently refocus the entire company in this direction.

Impact on Services

For your services team, the shift in thinking is a bit more subtle. It's really much more about urgency for them than it is specific line items such as we listed earlier. I like to boil it down to one statement: “In a recurring revenue business, there's no such thing as post-sales. Every single activity is a pre-sales activity.”

Contrast the urgency in implementing your software for a customer who is on a quarterly contract versus one who purchased a perpetual license. In the latter case, a project miss of two to three days or even a week probably doesn't matter that much. But for the customer who will have a decision point in 90 days (60 working days) on whether to keep your product, two to three days can make a huge difference.

Across the entire services team, this must be the mentality. The person taking a customer support call needs to think of the resolution of that problem as a pre-sales activity. Sales reps and solution consultants view every interaction with a customer as critical because the clock is ticking on the current month/quarter/year, and they need to get this deal closed. Customer support reps need to take on that same urgency. Resolving this problem for this customer as quickly as possible is mandatory because of the impending deal that could be hanging in the balance. That impending deal, of course, is the renewal or the opportunity to churn if there isn't a formal renewal or, in the case of a pay-as-you-go business, the opportunity to create a need for more of your product.

One of the jobs of a great CSM is to always be asking the question, “Why does this customer need my help right now? What could we do or what should we have done differently upstream so I would not be needed for this task?” This thinking often results in putting pressure on other parts of the services business:

- Customer support didn't adequately resolve a problem.

- A critical case is open for too long in customer support.

- The customer went through the training for how to build reports but does not understand how to build the reports they need.

- The configuration that the onboarding team did does not solve the use case the customer needs solved.

In all of these cases, the job of customer success (the CSM or her management) is not just to help get the customer over that challenge but to go to the source and apply pressure to ensure that the next customer does not end up in the same situation. This means going back to support or training or onboarding, forcing them to step up their game. Clearly, the best customer experience is not to have someone who can help when needed but needing that help less and less frequently.

To be fair, the same requirement exists for customer success to go back and challenge the non–services organizations when they've set the customer up for failure, too:

- Sales set the wrong expectations about what the product can do.

- The product does not function as promised.

But a large portion of the organizational influence that will allow customer success to deliver true success to your customers will take place within the services organization. That's why the urgency with which services approaches every task and challenge is paramount. They must begin to think of themselves as pre-sales people, not post-sales.

This is yet another reason why the VP of customer success must have real authority and possess true leadership qualities. So much of what she does to move your company forward has to do with influencing others who do not work for her. She needs to have the gravitas, incentive, and skills to go toe-to-toe with the VP of sales or the VP of engineering or the leaders of any of the other organizations. In many ways, the right customer success leader will bear a striking resemblance in skill set to your VP of sales with a little bit more of a service orientation instead of a closing mentality.