Everyone wants a better return on their money. It’s normal. With interest rates for savings accounts in the UK and US hovering under one per cent as of early 2021 (FXempire, 2022), people are looking for better ways to invest their money.

People are increasingly looking online to find investment ideas and opportunities. Cybercriminals are using this to their advantage. They have created a range of new online investment fraud attack methods to snare victims. How cybercriminals find their victims for this fraud is surprisingly easy, as you will learn in this chapter.

The online investment fraud attack methods will be evaluated in this chapter along with the techniques and tactics cybercriminals are using and how to defend yourself against them.

Consider these cases.

Jordan Belfort, aka The Wolf of Wall Street, is one of the most famous investment fraudsters of all time. His name is synonymous with boiler room scams. In 1989, he founded the brokerage Stratton Oakmont. It was a front for his boiler room operations – an army of high-pressure salesmen called victims to defraud them. Belfort was successful. He had a fleet of luxury cars, private planes, mansions and luxury yachts to show for it. Eventually, the law caught up with him and convicted him of stealing over $200 million from people. Many individuals lost their life savings to his team of fraudsters (Belfort, 2013).

Meet Jacob Keselman. He is the self-proclaimed Wolf of Kyiv (at least he says so on his Instagram account – why anyone would choose publicly to say they are following in Belfort’s fraudulent footsteps is a mystery). His Instagram account has pictures of him next to luxury cars with beautiful women. He is the CEO of Milton Group. Operating in Kyiv’s business district, he runs a sophisticated online equivalent of a boiler room scam. He, too, is thriving. In 2019, his operations made €65 million by fleecing thousands of victims around the world. Belfort would be envious. Except Keselman doesn’t need to call a ‘suckers list’ for victims. Today, victims come to him (OCCRP, 2020). As of September 2021, Keselman had not been arrested and Milton Group was still operating.

A boiler room is an operation – usually a call centre – where high-pressure salespeople call lists of potential investors (‘suckers lists’) to peddle speculative or fraudulent investments.

ANATOMY OF ONLINE INVESTMENT FRAUD

Investing is risky. Any financial product sold comes with a disclaimer similar to this: ‘the investment will go down as well as up, and you may not get back the whole amount that you invested’. However, for more complex, riskier investments, regulators require investors to go through an accreditation process. This is to protect novice investors from investing in products they do not fully understand.

Cybercriminals offer a range of investment pitches not easily understood by victims. Cryptocurrencies, wine, rare metals and alternative energy are examples of some of these. They claim they have discovered new ways of making money and invite unsuspecting individuals to join them, promising high returns on investments. In many cases, the offers can be up to 100 times the original investment. Those that do invest never see their money again. There is no regulator to warn them of the dangers.

To sum it up, online investment fraud is when a cybercriminal uses false or misleading information to convince a victim to make a purchase.

Thousands of global victims have lost their life savings to investment fraud. In the UK, between September 2019 and September 2020, Action Fraud received over 17,000 investment fraud reports. Victims reported £657.4 million in losses – a 28 per cent increase from the previous year (Action Fraud, 2020). A 2016 study from the Pension Research Council at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School found that 1 in 10 investors in the US fall victim to investment fraud during their lifetimes (Kieffer and Mottola, 2016).

LESSONS FROM HISTORY

Looking at historical cases of investment fraud, there is a theme that runs through them. Let’s begin by looking at two historical cases. The first is a case that, in retrospect, is hard to believe anyone would fall for. Yet, thousands did.

In 1818, young Gregor MacGregor left his native Scotland to seek adventure in Central America, Venezuela to be specific, to fight in their war for independence.

He spent two years getting to know the area and understanding the different cultures. On his return voyage back to London in 1820, he began to think about how he could make some money from all this knowledge.

When he arrived, he announced he had discovered a new country. It was called Poyais (supposedly located in modern-day Honduras). He invented marvellous stories about the riverbeds flowing through the lands filled with chunks of gold, just waiting to be picked up. He told how the King of Poyais was so taken in by him, he declared Gregor a prince of Poyais. The country was an unexplored paradise. It only needed a workforce to develop it.

He began a marketing campaign. First, he gave interviews with the leading national newspapers. Then he printed leaflets and ran advertisements. He wrote and published a 355-page Poyais guidebook that included maps of Poyais. Gregor sold the guidebooks throughout London and Edinburgh.

He began selling government bonds of Poyais. He raised over £200,000. Then he had fake Poyaisian land certificates created. By early 1823, 500 people had bought them.

People were excited about Poyais. At least seven ships set sail for it. They wanted a better life.

They didn’t get it. It didn’t take long for them to realise they had been duped by Gregor. Many people died of yellow fever and malaria while waiting to return home.

Gregor was able to run various Poyais schemes for 10 years until he could no longer get people to give him money. Here is the surprising part: people stopped investing due to diminishing returns. They didn’t stop because they thought his story was completely false. It didn’t occur to anyone that his entire story was a fraud.

In the end, he moved back to Venezuela and retired on a veteran’s retirement package supplied by the government (Allan, 2018).

Another case is that of Elizabeth Bigley, aka Cassie Chadwick.

It was 1905 in New York City. Andrew Carnegie was one of the wealthiest men in the world. He controlled the most extensive integrated iron and steel operations ever owned by an individual. Everyone knew who Andrew Carnegie was and that he lived in New York City.

Unknown to Andrew, something was about to hit him like a typhoon and cause such a scandal that it would eventually splatter his name across the front pages of newspapers worldwide.

Elizabeth Bigley was born in 1857. From an early age, she was continually getting in trouble with the law. In 1883 she married a doctor in Cleveland. It only lasted 12 days. During this time, she ran up huge debts in the doctor’s name. Twelve days was all it took before he realised he had been conned. The loan people eventually confiscated all his belongings, including his stethoscope.

Elizabeth conducted fraud to live an extravagant lifestyle. When she was caught, she moved on and started over. She found gullible men to marry her. Then she used her husbands to incur large debts.

In 1897, she was married for the third time. This time to another doctor named Leroy Chadwick. She assumed the name Cassie Chadwick. She hid her true identity and history from Leroy. Her husband was highly respected within the community. This gave her an air of respectability she hadn’t had previously. It was this she would take full advantage of for her next big fraud. It would make Cassie Chadwick an infamous household name.

In 1902, she travelled to New York City. There she stayed at Hanson House Hotel. The hotel was chosen because she knew an influential Ohio banker named Dillon would be staying there at the same time. He was an acquaintance of her husband.

She arranged for a chance encounter with him. During the meeting, she said she was there on private business and was just on her way to her father’s house. She asked if he would like to escort her. He agreed and held a carriage for her.

They went to 2 East 91st Street. It was the home address of Andrew Carnegie. She asked Dillon to wait in the carriage and walked by herself to the front door. She presented herself to the servants as someone thinking about hiring a maid named Hilda Smitch, who had once worked there. The servants didn’t know Hilda. She managed to extend the conversation to 30 minutes inside. To Dillon, it looked like she knew who lived there, or why else would she have been let in so easily?

As she walked back to the carriage, she pulled a large envelope from her bag. She made it appear she had received it from the house. She then confided in Dillon she was Andrew Carnegie’s illegitimate daughter and that he periodically gave her sums of money out of guilt and responsibility. She said the envelope contained two promissory notes valued at $5 million. She said she had others at home, and she would inherit millions when he died. Needless to say, Dillon was pulled into her story. He was intrigued and curious. She asked him not to tell anyone, knowing full well he would tell everyone.

In 1903, she went to the Wade Park Banking Company of Cleveland to deposit the notes. The bank manager, Ira Reynolds, was delighted to see her when she arrived. It was clear Dillon had been busy not keeping her secret.

She had a package that contained securities for $5 million and wanted to deposit them at his bank for safekeeping for several years. In 1907 she would come and collect them along with any interest the securities had earned.

She gave him a memorandum listing all the securities in the package. Reynolds should have inspected the contents himself before signing his name, but he didn’t. With that copy of the memorandum, she then had a receipt for $5 million that didn’t exist. The bank had unwittingly given their seal of approval that Cassie did indeed have $5 million stored there. With that, she could easily get more loans. It was something she began to do all over the country.

It didn’t take long for word to spread of Chadwick’s new wealth status. Bankers and investors felt this would be an extremely lucrative opportunity. They lined up to make money from Chadwick’s notes and future inheritance. They began offering loans of up to $1 million with a high-interest rate of 25 per cent. They were even generous enough to let the loans compound annually and not demand any repayment until the loan was due. They calculated that Carnegie would honour any of the debts, and they would eventually get paid once she got her inheritance at some future point. These investors and bankers were intelligent, highly educated and successful. None of them did the necessary due diligence one would expect when getting a loan from their bank.

Carnegie was never asked about Cassie.

Wise bankers should have been suspicious of that, but most of them couldn’t see past the lucrative deal in front of them. To the bankers, there appeared to be no risk…

Chadwick took full advantage of the situation. She began to live like a queen. Eventually, she began to be known as the ‘Queen of Ohio’. She began entertaining the wealthy, even hosting a dinner party costing $100,000. She insisted on always paying the highest price for goods.

Eventually, her story began to unravel. It was slow at first. She was a master at delay tactics. She managed to delay being discovered for many months. It wasn’t until an investor named Herbert Newman from Boston said enough was enough. In 1904, he had his lawyers go to Reynolds’ bank and force him to turn over the contents of Chadwick’s package to inspect the notes. Once they looked, it was evident they were forgeries. Her time was up. In 1905 she was convicted and sentenced to 14 years in prison for her crimes. Her health quickly deteriorated, and she died in October 1907, a completely broken woman.

Keep an eye out for stories that don’t add up. This suggests something is not right, and you need to be extra vigilant.

Her reasoning when beginning the fraud was that no one would ask Carnegie about an illegitimate child for fear of embarrassing him. Surprisingly, this proved correct. Not a single banker in Ohio thought to verify her story with Carnegie. In the end, it is estimated she amassed total debts close to $5–20 million (Docevski, 2016). The final number was never known. This is most likely due to certain bankers and individuals not wanting to admit they were foolish enough to fall for such a fraud. There would have been significant reputational damage.

Fast forward to the 1990s, and here are two of the more unique investment fraud pitches: 20 per cent return on your money by investing in an eel farm? Does the prospect of reverse-ageing water from a newly discovered ‘Fountain of Youth’ sound enticing? (Rehak, 1995).

Notice the theme here? There is always an exciting ‘get rich, easy’ pitch that is used that isn’t easily verifiable. The average person isn’t going to know much about eel farms and no one is going to be an expert in something that doesn’t exist like reverse-ageing water.

Gregor was selling fraudulent investments for a country no one had ever seen. It’s safe to say none of his investors were experts on Poyais. Cassie came up with the outlandish story about being Carnegie’s daughter that everyone believed at face value without bothering to verify it.

ONLINE INVESTMENT FRAUD ATTACK METHODS

The attack methods in this section are common tactics used by cybercriminals in their online investment frauds. They spend considerable time and effort making themselves look trustworthy and credible to potential victims.

Fake websites

Cybercriminals create fake investment websites (for example cryptocurrencies, foreign exchange trading) and victims are lured into investing small amounts on fake trading platforms. In many cases, the platforms are for complex financial products. Within a short period of time, their initial investment shows fantastic returns. They then feel more confident investing more money. Everything goes well until the victim tries to withdraw the money. There are cases where the victim is told they must pay a transfer fee or a tax before getting their money – another way to get more money from the victim. No one gets their money back.

Figures 4.1 and 4.2 are the Mirror Trading International company, which has the dubious honor of being the most significant cryptocurrency online investment fraud in 2020, taking in $589 million worth of cryptocurrency from more than 471,000 deposits. This suggests there were hundreds of thousands of victims (Chainalysis, 2021).

In Figure 4.2, Mirror says that your Bitcoin will accumulate daily without any action from you. All you need to do is sit back and watch your money grow; they will take care of the rest.

Figure 4.1 Mirror Trading website homepage

The only people having their money accumulate is the cybercriminals behind the operations. As of the time of writing, the web page is no longer live.

Cloning genuine investment firms

Cybercriminals are setting up replica websites of legitimate investment firms (Peachey, 2021). Ads on social media and search engines take victims to these sites. The victims register their interest. Cybercriminals then begin launching their investment fraud and start calling. Often the returns offered on these sites are modest, only slightly better than the market rate. This is appealing to more long-term risk-averse investors.

Figure 4.3 is an example of a cloned website for the UK investment company Interactive Brokers. The official website domain is www.ii.co.uk. The cloned websites used www.iipro.co.uk and www.ii-trade.co.uk. The websites do not need to be exact, they only need to have a similar look and colours. This is because most victims are new customers.

Look at the website address. Are there subtle changes to the name? If yes, it could mean it’s a fake. Spend time searching online for the organisation’s official website and confirm the website is authentic.

In some cases, the victim is at serious risk of identity theft if they enter their personal details on fraudulent websites (Cavaglieri, 2021). More on this in Chapter 5.

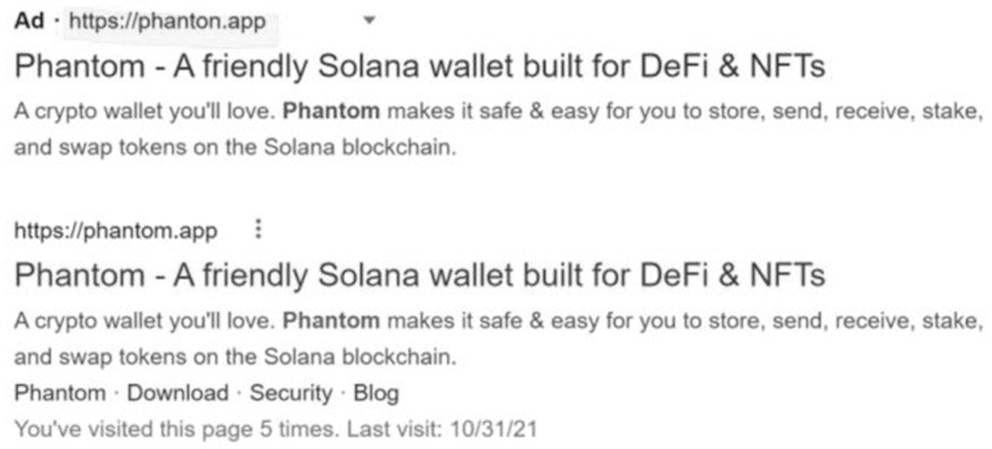

Be cautious of paid search engine ads. These are usually boxed adverts showing at the top of search engine results pages. The official website is often one of the top showing non-paid results (Which.co.uk, 2021). Compare website links before you click to see if you can spot anything out of place.

Figure 4.3 Cloned Interactive Investor website (Source: Cavaglieri, 2021)

Note: This image is a cloned website. People are directed to a fake sign-up page asking for lots of personal details.

Social media attacks

When cybercriminals use social media, the average age of victims drops. In 2021, the City of London Police reported that when social media is mentioned by investment fraud victims, 27.5 per cent are aged 19–25. When social media isn’t a factor, the average age of victims is over 50 (FawleyOnline, 2021).

According to a study done by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), people under 25 are six times more likely to trust investment offers they receive via social media than over 55s (FCA, 2018). Social media is luring young people who are more susceptible to cybercriminals’ techniques.

Cybercriminals use all social media platforms to lure victims. They create fake accounts or, in some circumstances, take over an existing legitimate account. Then they post images, videos or messages showing how much money they are making. It could be someone sitting in a private jet or driving an expensive car. The message they send is ‘you too can be this wealthy’ if you follow their investment advice – which is, of course, to send them money.

Consider this case.

‘I was following this guy on Instagram, and he always posts with his car, a rose gold Maserati, saying that he’s rich and self-made and really young, he’s only 21,’ said Jonathan Reuben, 24, an accountant.

The cybercriminal Jonathan was following explained how he became wealthy through foreign exchange trading. He began offering his followers the chance to get in on his get-rich-quick schemes. Jonathan decided to give it a try. He put in some money and soon saw his profits rise. Jonathan added more and more money to his account. When he tried to withdraw his money months later, he couldn’t.

‘At first, I put in £1,000, and once I saw I was getting money, I deposited a bit more and more. In the end, I was scammed out of £17,000,’ he told the BBC’s Money Box programme (Graham, 2021).

Advertisement attacks

Cybercriminals run a stream of fraudulent investment advertisements on social media platforms and search engines. It is evident from the number of victims falling for these deceitful ads, that the fraud controls of these platforms are poor.

The cybersecurity company Checkpoint published research in November 2021 showing how this works. They found cybercriminals were attempting to ensnare people searching for the popular crypto wallet company Phantom, by running Google ads under the name phanton.app. Notice in Figure 4.4 that the website address is almost identical to the official phantom.app website. There is hardly any difference in the wording either.

Once victims click on the ad, they are sent to a fake website. The unsuspecting victim would then create an account on the fake website and any money they transferred in would go directly to the cybercriminals (Barda et al., 2021).

Professional-looking websites, adverts or social media posts don’t always mean that an investment opportunity is genuine. Cybercriminals can use the names of well-known brands or individuals to make their frauds appear legitimate.

Genuine online businesses can display these ads unknowingly on their websites. Many use Google’s AdSense to serve their ads, which serves ads automatically without the businesses seeing them or approving them beforehand. They trust Google. Victims assume there has been some type of filtering process and the companies are genuine, or they would not have appeared on legitimate websites.

There are two main types of ads Google offers: a display ad – which appears in major publications like national newspapers, and keywords – when users search on Google, specific terms will generate targeted adverts. Cybercriminals use both forms.

In January 2022, the Goldman Sachs-backed digital bank Starling boycotted Meta, which owns Facebook and Instagram, for failing to tackle fraudulent financial adverts. In the bank’s annual letter, the CEO and founder, Anne Boden, had this to say:

We want to protect our customers and our brand integrity. And we can no longer pay to advertise on a platform alongside scammers who are going after the savings of our customers and those of other banks.

(Browne, 2022)

Which.co.uk decided to find out how easy it is to post fraudulent ads on Google and Facebook. In early 2020, Which? created a fake water brand, Remedii. Next, they made an accompanying online service offering pseudo health and hydration advice called Natural Hydration. First, they targeted Google. They easily bought Google AdWords, promoting their fake information and website. Any users searching for terms like ‘bottled water’ would see the ads. The ads were getting nearly 100,000 impressions over a month. They even appeared above the NHS’s website. Which.co.uk made dubious claims like their water would help you ‘lose weight, improve your mood and make you feel better’.

On Facebook, they created a page for ‘Natural Hydration’ and filled it with pseudo advice on health and plugs for their fake brand. Then they paid to promote their brand. They had over 500 likes within a week.

Harry Rose, Which? magazine editor, said:

Tech giants earn billions from advertising and should be putting more resources into preventing fraudsters from abusing their platforms, so consumers can trust that the adverts they see are legitimate.

(Laughlin, 2020)

Phone attacks

Remember the ‘suckers lists’? Anytime someone enters their contact details on a fraudulent investment website, they are on the list. It doesn’t matter if they have invested or not. They will be targeted and called by cybercriminals. High-pressure boiler-room tactics (for example get victims in an emotional state and use different persuasion techniques to get them to invest) will probably be used.

Don’t be rushed into making an investment. Reputable investment organisations will never pressure you into making a transaction on the spot.

In many circumstances, the attack methods discussed are used together. A victim could see a fraudulent ad, which would lead them to a fake website. As the victim looks for more information about the company, they could also encounter fraudulent Facebook groups and reviews. All of these used together can further give the appearance the company is legitimate and, therefore, a safe place to invest their money.

Fake celebrity endorsements attacks

Cybercriminals create websites or online articles that make fictitious claims from celebrities that supposedly endorse the investments the cybercriminals are selling. Many show the celebrities endorsing cryptocurrency investment schemes for example. It could be any online investment, though.

Two celebrities (Richard Branson and Martin Lewis) are referenced in the bulk of the fraudulent endorsements, according to the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) in the UK (NCSC, 2020). Depending on where you are in the world, the ads will feature celebrities in your area. False testimonials and pictures of the celebrities are used.

The NCSC found that the fake articles are promoted in mass email campaigns along with SMS messages and online adverts. To get an idea of the scale of the problem, from May to December 2020, the NCSC removed over 730,000 websites running these frauds (NCSC, 2020). It is a growing problem. Take a look at Figure 4.5. These are two online ads the NCSC took down. Cybercriminals used legitimate, well-known newspaper brands to make it appear the ads were actual news articles appearing in their newspapers. These are fake endorsement ads (Tidy, 2021).

Figure 4.5 Fake celebrity endorsement advertisements (NCSC) (Source: Tidy, 2021)

The individuals and publishers featured in the fraudulent ads in Figure 4.5 are not aware of their use, nor are they involved in the frauds in any way.

Ian Levy, the NCSC’s technical director, said ‘Criminals use both newspaper brands and celebrities combined to make these articles look really good’ (Tidy, 2021).

Consider this.

An online investment fraud case, reported by a UK victim in 2020.

The victim had received a large chunk of money the previous year; it was stored in a savings account. One day she was scrolling through Facebook when she saw an advert about how Bitcoin investments were making a great return. She found it difficult to make any money on her savings accounts and investments, so she responded to the ad to learn a bit more. She didn’t know much about Bitcoin or cryptocurrencies. The salesman who called her said not to worry about it; she didn’t need to know anything about Bitcoin. She would be assigned a handler to take care of her investment.

The handler recommended she start with a small initial investment to test it out. She was getting contacted through WhatsApp as ‘support’. Everyone at the company was professional and friendly. She was excited. Her investment started showing a profit. She was encouraged to invest more, which she did. She trusted them.

Then she started to get messages pressuring her to send more money. Her handler said there had been a blimp in the cryptocurrency market, but with another significant investment, she would make her money back plus more. She stopped sending money, but the messages kept coming. Dozens a day pressuring her to send more money. Finally, she had enough and asked for her money back. She was told it wasn’t possible and that she actually owed money to cover her losses.

In the end, she had transferred £210,000. It was her entire savings. When she started investigating, she discovered that even though the company used UK phone numbers, they were not registered in the UK. She found lots of the five-star reviews were fake, and hundreds more said the service was a scam.

She is now living paycheck to paycheck and no longer has the financial security she once had. She feels powerless (Derbyshire Constabulary, 2020).

Affinity fraud

Affinity fraud targets groups of people who know each other. They are identifiable groups like professional networks, religious associations or ethnic communities. Communication tools like social networks, chat rooms and email are used to share the investment fraud scheme. Often friends and family innocently share the information, not realising it’s a fraud. This fraud is a good example of Cialdini’s consensus persuasion principle. It’s easier to convince people to invest if people they know and trust are doing so.

Pyramid schemes

Some of the most well-known investment frauds in recent history have been pyramid schemes. The first large-scale pyramid scheme was run by Charles Ponze in the early 1900s in the US. He conned an estimated 40,000 people out of $15 million before getting arrested. It’s because of him, pyramid schemes are often referred to as Ponzi schemes (Kiger, 2019).

Ponzi schemes are ‘get-rich-quick’ investment scams that pay returns to investors from their own money, or from money paid in by subsequent investors. There is no actual investment scheme as the fraudsters siphon off the money for themselves (Action Fraud, no date).

Pitches sent or advertised to victims promise outlandish returns like ‘you can make big money from home’ or ‘turn £100 into £10,000 in only four weeks’. Victims are told they will make more money by getting other people to invest as well. They end up recruiting friends, family or co-workers. Unfortunately, the investment never existed. Early investors are paid from the contributions of newer investors. In the end, the scheme collapses when the number of new investors start to decrease.

Pump and dump schemes

Pump and dump schemes promise incredible returns for purchasing low-priced stock. Unknown to the investor, the cybercriminal promoting the stock usually owns a large amount of it. Once more and more investors start buying the stock, the price of the stock jumps. The cybercriminals will then sell off their shares, leaving the investors with worthless stock.

ONLINE INVESTMENT FRAUD PLAYBOOK

The most critical step for cybercriminals running online investment frauds is their pitch. How do they get victims to respond to them? There must be a compelling lure. It needs to be something exciting, ideally not something easily understood, so cybercriminals can more easily persuade their victims, such as with cryptocurrencies.

Few things have captured the public’s imagination in recent years as much as cryptocurrencies, especially the most prominent cryptocurrency, Bitcoin. Take the case of Kingsley Advani, who became a Bitcoin millionaire with a modest investment of $24,000 by the time he turned 24 (Rhodes, 2018).

There is story after story in the news about people getting wealthy through cryptocurrencies. The stories make it appear it’s easy to get rich through an investment in them. This makes them attractive for cybercriminals to use. Who doesn’t want to be a cryptocurrency millionaire?

But what are cryptocurrencies? At the basic level, cryptocurrency is digital money. It’s unlike any type of money ever created with no physical form and no central authority like a government to manage it. It is a revolutionary idea. There is a great deal of uncertainty about the future of cryptocurrencies; no one knows if the technology is here to stay or if it is just a fad.

Bitcoin, which launched in 2008, was the first cryptocurrency, and it remains by far the biggest, most influential and best-known. Now though, there are a dizzying number of different cryptocurrencies (as of 2022, there were thousands of cryptocurrencies listed on CoinMarketCap (no date), the price-tracking website for cryptocurrencies). They all operate in slightly different ways that would probably baffle most people.

What makes Bitcoin appealing to cybercriminals is its decentralised, secure and anonymous features. Since no one controls Bitcoin, there is no one to stop cybercriminals from using it. It carries far greater risks; with no banks or central authority, there is no recourse when funds are stolen. Another risk is that once payment has been made in Bitcoin, that’s it. No bank or credit card company like MasterCard or Visa can reverse or cancel the transaction if it’s determined you were a victim of fraud. It’s a one-way transaction.

There is a lot of mystery surrounding cryptocurrencies. Many people are confused by the concept yet are attracted by how much money there is to be made. This is a crucial reason why cybercriminals are using cryptocurrencies in their online investment pitches. When selling to victims, they focus their attention on the phantom wealth they will make by investing.

Once someone has responded to the cybercriminals’ pitch, the attack usually moves to a telephone call. Cybercriminals have set up call centres, employing thousands of people all over the world. At first glance, it would be hard to distinguish between a legitimate call centre versus one run by cybercriminals.

Sales training is given to all staff, often in the same way any call centre would be run. They are taught different selling techniques depending on where the victim is located. The goal is to establish rapport with the victim and create trust with them as fast as possible.

The operators are trained to customise their pitches to make them unique to the individual. They want to find out what makes the victim tick, what the emotional driver is for investing. In this case, the playbook is similar to that of advance-fee frauds. Find out the victim’s emotional drivers, then use various persuasion techniques focused on them until they pay up (OCCRP, 2020).

Cybercriminals begin to groom their victims from the first call. It isn’t enough to have veneers of professionalism like professional looking websites, slick brochures and well-presented salespeople. They want the victim to have an emotional attachment to them. Cybercriminals groom victims by using methods like these:

- building friendships and trust;

- flattering the victim and appealing to visceral feelings;

- making victims feel indebted to them;

- isolating them from their financial and social networks;

- manipulating the victim’s behaviour by giving and withholding their friendship.

It is essential to understand lone cybercriminals do not run online investment frauds. Organised cybercriminal gangs do. They are well managed and run as any global business would run. Except, in this case, they are for illegal purposes. Police have discovered full-scale operations in numerous countries. Consider these cases:

- In June 2021, Thailand police shut a cryptocurrency investment call centre operation employing 60 people (CTN News, 2021).

- Europol reported online investment fraud scheme call centres run in Bulgaria and North Macedonia in May 2021. Israeli nationals organised the fraud scheme (Europol, 2021).

- In 2020, Eurojust, the EU Agency for Criminal Justice Cooperation, in coordination with Austria, Bulgaria, Germany and Serbia, took down two organised criminal groups suspected of large-scale investment fraud in cyber trading. Thousands of investors lost all their money (Eurojust, 2020).

Often the victim is convinced to start off by giving a small amount just to get their feet wet. The victim then starts to see significant returns on their money quickly – they are generally given access to fake investment websites. On these sites, the incredible returns shown are fictitious but they encourage the victim to give more and more. Meanwhile, they keep checking the website, their return on investment continues to grow and grow. This illusion usually continues until the victim wants to withdraw their money. They are never able to withdraw their money and are given excuse after excuse why not.

CASE STUDY – MILTON GROUP

Let’s take a closer look at the Milton Group in Ukraine. In 2020, a whistle-blower provided the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) with evidence of how they run their operation. Armed with this, reporters from 21 countries and dozens of media outlets spoke to more than 180 victims from all over the world, from Sweden to Ecuador to Australia.

Many reported they responded to an ad on Facebook that promised remarkable returns on investments. After entering their contact details to find out more, victims would be deluged with high-pressure sales calls. After initially investing a small amount (between $100–$300), the victims would see their investments soar on screen. This encouraged them to invest more. In some cases, when victims ran out of money, Milton would harass victims to keep investing by borrowing the money. Many victims reported taking out huge loans. A favourite phrase Milton used on victims was, ‘You will never regret this decision.’

Milton Group has a dedicated team called the ‘retention’ team. Whenever a victim is apprehensive or wants to withdraw their money, they are escalated to the retention team. This team is trained to launch a new array of frauds on the victim to get even more money from them.

Here are some of their techniques:

- Tell the victim there is a 20 per cent tax due on their investment. This needs to be paid first before they can receive their funds.

- Victim receives a call telling them the company has collapsed and been taken over by the UK government. The government will send them their money directly for another up-front fee. The fee is usually to another person outside the UK.

- Fake lawyers contact the victim, offering to get their money back for a fee.

- A fake money laundering officer calls the victim threatening them. Everything will be OK if the victim pays a fee.

When needed, the retention team creates forged documents from official government organisations like the UK revenue and customs service or banks like Barclays. They will go to great lengths to try to show the victim proof they are telling the truth (OCCRP, 2020).

Aleksander Fjeldvær, head of cybercrime for Norway’s biggest bank, DNB, said banks there were vigilant, but often struggled to convince customers that they were being scammed due to how realistic the fraudsters’ technology was and how intense their psychological manipulation was.

‘Anyone can be fooled,’ he said. ‘It is understandable that if you see your investment and talk to an extremely convincing person, that you believe this’ (OCCRP, 2020).

Cybercriminals create fake review websites

What is one thing most people do when they want to learn about a new company? They do an online search. You want to know what other people are saying about it, whether it has a good or bad reputation or reviews. A study by the FCA found 23 per cent of victims said that online customer testimonies and reviews increased their trust in investment companies (FCA, 2018). Cybercriminals understand the importance of positive reviews and testimonials.

Cybercriminals set up fake investment review websites (OCCRP, 2020). When searching online, victims often come across these sites first. They are fooled into thinking the website is a legitimate third-party review of the investment company. When they see positive reviews, it can make them feel more confident about investing their money.

When looking at reviews and testimonials, keep a healthy degree of scepticism. Ask yourself, who is giving the review? Is the review from a leading investment website like the Financial Times or the Wall Street Journal? Have any legitimate financial news organisations reported on them before? If you cannot find anything, be extra cautious.

Be wary of any website claiming they are exposing cryptocurrency frauds. In many circumstances, this is done to make them appear trustworthy to victims when, in reality, they may only be trying to direct you to another fraudulent website.

Cybercriminals hide where the investments are located

While St Vincent and Grenadines in the Caribbean is known for its beautiful beaches and scenery, there is a darker side. It is also a well-known offshore financial centre (Trigger, 2020). The government does not regulate currency trading businesses registered on the island. They also have one of the most stringent confidentiality laws in the world. Both of these reasons make St Vincent and the Grenadines appealing for cybercriminals.

Victims think they are dealing with a regulated firm in a reputable country. They falsely assume there are safeguards for their investments. Cybercriminals will lead them to believe this; there may be phone numbers and addresses listed from the reputable country. Sadly, it is not the case. When victims send money, it is sent to offshore havens like St Vincent and Grenadines. From there, they will enter a global spiderweb of transactions. All of it is designed to confuse investigators who might start enquiring. For the victim, once the money enters these jurisdictions, they are not getting any of their funds back.

Most countries regulate the buying and selling of securities. The US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the UK’s FCA are two examples. Besides stocks, investments like cryptocurrencies, wine and many other things are not subject to many laws and regulations that exist to protect investors. In other words, if you invest in these types of things, there is little that exists to protect you.

Cybercriminals target overconfidence

How many people meet the following description?

- self-reliant when it comes to making decisions;

- optimistic;

- above-average financial knowledge;

- above-average income;

- university-educated;

- open to listening to new ideas or sales pitches.

This is a profile of the primary target for investment fraud. Historically, it has been assumed victims were isolated, frail and gullible. Research has shown this is not true. There is a mystery here. Why would someone with more financial knowledge be more susceptible to investor fraud? It comes down to one word: overconfidence (FINRA, 2020).

Overconfidence has always been the Achilles heel for investors. Investors often have an overinflated assessment of their own investment skills, intellect or talent in selecting suitable investments. In short, they have an egotistical belief that they are better than they are at investing. Many investors have lost money because of this.

Victims mistakenly believe they can tell a fraudulent investment pitch from a genuine investment pitch. They don’t recognise the psychological persuasion skills cybercriminals employ on them. When they decide whether to invest, they will analyse the opportunity as they would any other investment. They will look at all the facts available to them. However, the facts themselves are often lies or misleading. Their decision is based on inaccurate and incomplete facts.

Review all the persuasion techniques and defences outlined in the previous chapters. The same methods are used for investment fraud schemes. For example: scarcity – there is pressure to invest now; reciprocity – the caller has given you a small gift and now expects you to reciprocate; principle of liking – you begin to bond with the salesman, you trust what he is saying.

HOW ARE PEOPLE IMPACTED?

According to Victim Support in the UK, cybercrime causes the same emotional, physical and financial trauma as a crime in the physical world. In some cases, the trauma is greater due to the victim losing their life savings or business. Victims feel shame and embarrassment for allowing themselves to get manipulated by cybercriminals.

The critical thing to understand is that the victim is not to blame (Victim Support, no date). Cybercriminals are responsible for these crimes.

Everyone is impacted differently by cyber fraud and will react in their own way. Physical reactions can be headaches, body aches, difficulty breathing, nausea and stomach upsets. Forgetfulness, difficulty thinking clearly or having trouble concentrating can occur. Others have nightmares and panic attacks as their anxiety levels go up. Sadness and grief for what the victim has lost can set in. Victims can also experience flashbacks. These are normal reactions to suffering an overwhelming event (Victim Support, no date).

FOR ADDITIONAL HELP:

https://victimsupport.org.nz/sites/default/files/

2021-01/Coping with Trauma.pdf

https://victimsupport.org.nz/sites/default/

files/2021-01/When you are Grieving.pdf

https://victimsupport.org.nz/sites/default/files/

2021-01/Dealing with flashbacks.pdf

Most cyber frauds employ an element of social engineering. Cybercriminals want to influence the behaviour of their target victims for online investment fraud. An important tool for them in the future will be AI.

AI is the ability of a machine to display human-like capabilities such as reasoning, learning, planning and creativity. AI systems can adapt their behaviour to a certain degree by analysing the effects of previous actions and working autonomously (European Parliament, 2021).

Expect cybercriminals to weaponise AI to assist with the scale and effectiveness of their social engineering attacks. Imagine cybercriminals using AI to spot patterns in behaviour or to better understand their victims’ vulnerabilities to exploit them more easily. It will be like turboboosting the social engineering techniques cybercriminals currently employ.

In addition, with the amount of data online about the average person, AI can be used to do more precise targeting of victims. What if AI could be used to determine if a target has characteristics like optimism, self-reliance or has above-average income? Or when the victim is in an emotional state? Or if AI could predict which investment ideas excited someone more – is it cryptocurrencies or maybe investing in flying cars or who knows?

All of these are real possibilities. While the cybercriminal attack methods will evolve, what will not change is that there will always be an offer to get fabulously rich in something that the average individual does not easily understand.

DEFENDING AGAINST ONLINE INVESTMENT FRAUD

Cybercriminals will continue to change their sales pitches and attack methods. By following the guidelines here, it will not matter what pitch they throw at you; you will be better prepared to recognise the attacks as frauds when they happen.

Preventative measures

The best prevention for online investment fraud is to understand the cybercriminal’s investment fraud playbook. This way you will better recognise a dishonest sales pitch when you see it. Here are things to keep in mind:

- Watch out for promises that offer high returns with low risk. Terms like ‘guaranteed return on investment’ are used. Remember, risk and reward go hand in hand. Claims such as ‘risk-free’, ‘zero risk’, ‘absolutely safe’ and ‘guaranteed profit’ are hallmarks of fraud.

- Only invest in what you know. Do not believe the salesperson. Always research any investment.

- Look at reputable publications like the Financial Times and legitimate review websites like Trustpilot for the company you’re considering investing with.

- Remember well-presented websites and glossy-looking marketing material doesn’t mean it is a legitimate company. Cybercriminals can use the names of well-known brands or individuals to make their fraud appear legitimate.

- Bear in mind that just because a company is registered at a prestigious address like Canary Wharf or Mayfair in the UK doesn’t mean they operate there. It is easy to rent virtual space to enhance business status.

Warning signs

Do your due diligence for new investments before sending any money. Here are some warning signs things might not be as they appear:

- Is the investment company based offshore? Learn where the investment and the investment professional are registered. Be extra wary if it’s an offshore operation. It will be difficult to recover any funds if the company is offshore.

- Is there complicated jargon and language used that is difficult to understand? This is done on purpose to confuse victims. Often cybercriminals will claim their technology is highly secretive and say you shouldn’t worry about the details.

- Is the investment company pressuring you to invest more and more money? Do you feel pressured to do so? These are warning signs that something isn’t right.

There are times when you are not sure you are a victim of investment fraud but you may be suspicious. In these situations, speak to trusted friends or family members or seek independent professional advice. Cybercriminals will try to discourage you from doing so – this should be a warning sign and reconfirm the urgent need to speak to someone about your situation.

What to do if you are a victim

There is support if you fall victim. Actionfraud.police.uk (UK) and usa.gov (USA) are good places to go to. Here are some further steps to take:

- Report the investment fraud. In the UK, report it to Action Fraud, https://www.actionfraud.police.uk/ and the FCA, www.fca.org.uk. In the US, you can report it to https://www.justice.gov/fraudtaskforce or www.ic3.gov

- Contact the financial institution you paid the cybercriminal from to report the fraud. There are some instances where you may be reimbursed by the financial institution.

- Start a fraud file to keep as evidence. It should include the cybercriminal’s name and contact details, cybercriminals’ website URL, timeline of events, bank statements with evidence of the investment and police report (St Pauls Chambers, 2020).

Which? offers guidance on the ways victims can get their money back: https://www.which.co.uk/consumer-rights/advice/how-to-

get-your-money-back-after-a-scam-amyJW6f0D2TJ

SUMMARY

It’s easy for cybercriminals to attack people through online investment fraud. They only need to buy ads on large internet platforms, then build professional-looking websites and fake trading platforms. They do not want to steal your money by force or through extortion, they want you to happily send them your money willingly.

As you have seen in this chapter, it is disturbingly easy for cybercriminals to find victims for their online investment frauds. The fact they use well-known internet companies to find victims is worrying. As outlined in this chapter, everyone needs to be aware of the dangers lurking on these platforms and take appropriate precautions. By understanding their methods, you will have a better chance of recognising the frauds for what they are when you encounter them.

One final thing on online investment fraud to always remember: do not invest in anything you do not entirely understand, no matter how great the potential returns may appear to be. These investments are complex for a reason – to keep victims in the dark that they are frauds.

REFERENCES

Action Fraud (2020) Action fraud warns of rise in investment fraud reports as nation enters second lockdown. Available from https://www.actionfraud.police.uk/news/action-

fraud-warns-of-rise-in-investment-fraud-reports-as-

nation-enters-second-lockdown

Action Fraud (no date) Ponzi schemes. Available from https://www.actionfraud.police.uk/a-z-

of-fraud/ponzi-schemes

Allan, Victor (2018) Gregor MacGregor, the Prince of Poyais. History Today. Available from https://www.historytoday.com/miscellanies/gregor-

macgregor-prince-poyais

Barda, Dikla, Zaikin, Roman and Vanunu, Oded (2021) CPR alerts crypto wallet users of massive search engine phishing campaign that has resulted in at least half a million dollars being stolen. Research.checkpoint.com. Available from https://research.checkpoint.com/2021/cpr-alerts-

crypto-wallet-users-of-massive-search-

engine-phishing-campaign-that-has-resulted-in-at-

least-half-a-million-dollars-being-stolen/

Belfort, Jordan (2013) The Wolf of Wall Street. London: Two Roads.

Browne, Ryan (2022) Goldman-backed digital bank Starling boycotts Meta over scam ads. cnbc.com. Available from https://www.cnbc.com/2022/01/07/goldman-backed-digital-

bank-starling-boycotts-meta-over-scam-ads.html

Cavaglieri, Chiara (2021) Fraudsters peddling fake Interactive Investor and ING Bank investments warns Which?. Which.co.uk. Available from https://www.which.co.uk/news/2021/05/fraudsters-peddling-

fake-interactive-investor-and-ing-bank-

investments-warns-which/

Chainalysis (2021) The Chainalysis 2021 crypto crime report. Available from https://go.chainalysis.com/2021-Crypto-

Crime-Report.html

CoinMarketCap.com (no date) Today’s cryptocurrency prices by market cap. Available from https://coinmarketcap.com

CTN News (2021) Police take down foreign cryptocurrency call center in northern Thailand. Available from https://www.chiangraitimes.com/thailand-

national-news/police-take-down-foreign-cryptocurrency-

call-center-in-northern-thailand/

Derbyshire Constabulary (2020) A victim’s story: How investment scammers tricked me out of £210,000. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hY6gfmJAG-Y

Docevski, Boban (2016) The turbulent life of Cassie Chadwick – The impostor who claimed to be Carnegie’s illegitimate daughter. Vintage News. Available from https://www.thevintagenews.com/2016/11/22/the-turbulent-

life-of-cassie-chadwick-the-impostor-

who-claimed-to-be-carnegies-illegitimate-daughter/

Eurojust (2020) Action against large-scale investment fraud in several countries. Available from https://www.eurojust.europa.eu/action-against-large-

scale-investment-fraud-several-countries

European Parliament (2021) What is artificial intelligence and how is it used? Available from https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/society/

20200827STO85804/what-is-artificial-intelligence-

and-how-is-it-used

Europol (2021) Trading scheme resulting in €30 million in losses uncovered. Available from https://www.europol.europa.eu/newsroom/news/trading-

scheme-resulting-in-€30-million-in-losses-uncovered

FawleyOnline (2021) New figures reveal how much victims lost to investment fraud scams on social media. Available from https://www.fawleyonline.org.uk/new-figures-reveal-how-much-victims-lost-to-investment-fraud-scams-on-social-media/

FCA (2018) FCA warns of increased risk of online investment fraud, as investors lose £87k a day to binary options scams. Available from https://www.fca.org.uk/news/press-releases/fca-warns-increased-

risk-online-investment-fraud-investors-scamsmart

FINRA (2020) Fighting fraud 101. Available from www.FINRAFoundation.org

FXempire (2022) Global macro indicators. Available from https://www.fxempire.com/macro

Graham, Darin (2021) I was scammed out of £17,000 on Instagram. BBC. Available from https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-55804205

Grzegorczyk, Marek (2021) Ukraine is failing to tackle its scam call centres. Emerging Europe. Available from https://emerging-europe.com/news/ukraine-is-failing-to-tackle-its-scam-call-centres/

Kieffer, Christine N. and Mottola, Gary R. (2016) Understanding and combating investment fraud. Pension Research Council Working Paper, Pension Research Council. Available from https://pensionresearchcouncil.wharton.upenn.edu/wp-

content/uploads/2016/07/PRC-CP-2016-11-

Kieffer-Mottola.pdf

Kiger, Patrick J. (2019) The shady, get-rich scams of the roaring twenties. History.com. Available from https://www.history.com/news/roaring-twenties-

scams-ponzi-wall-street#section_2

Laughlin, Andrew (2020) Fake ads; real problems: How easy is it to post scam adverts on Facebook and Google? Which.co.uk. Available from https://www.which.co.uk/news/2020/07/fake-ads-

real-problems-how-easy-is-it-to-post-scam-

adverts-on-google-and-facebook/

NCSC (2020) Active cyber defence: The fourth year. Available from https://www.ncsc.gov.uk/files/Active-Cyber-Defence-

ACD-The-Fourth-Year.pdf

OCCRP (2020) Trail of broken lives leads to Kyiv call center. Available from https://www.occrp.org/en/fraud-factory/trail-of-broken-

lives-leads-to-kyiv-call-center

Peachey, Kevin (2021) Victims typically lose £45,000 each owing to investment scams. BBC. Available from https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-55816059

Rehak, Judith (1995) From boiler room to chat room: Investment fraud on the internet. New York Times. Available from https://www.nytimes.com/1995/11/11/your-money/

IHT-from-boiler-room-to-chat-roominvestment-

fraud-on-theinternet.html

Rhodes, Delton (2018) The untold Bitcoin stories of Bitcoin millionaires. CoinCentral. Available from https://coincentral.com/the-untold-bitcoin-

stories-of-bitcoin-millionaires/

St Pauls Chambers (2020) 5 step recovery for victims of investment fraud scams. Available from https://www.stpaulschambers.com/five-step-recovery-for-

victims-of-investment-fraud-scams/

Tidy, Joe (2021) Martin Lewis and Sir Richard Branson’s names most used by scammers. BBC. Available from https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-57051546

Trigger, Rebecca (2020) The cyber pirates of the Caribbean. ABC.net.au. Available from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-01-06/cyber-

pirates-of-the-caribbean-online-fraud-

scheme/11719724?nw=0

Victim Support (no date) Cybercrime and online fraud. Available from https://victimsupport.org.nz/get-support/other-crimes-

or-incidents/cybercrime-and-online-fraud