Chapter 8

Passwords

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Selecting passwords

Selecting passwords

![]() Discovering how often you need to change passwords — or not

Discovering how often you need to change passwords — or not

![]() Storing passwords

Storing passwords

![]() Finding alternatives to passwords

Finding alternatives to passwords

Most people alive today are familiar with the concept of passwords and with the use of passwords in the realm of cybersecurity. Yet, there are so many misconceptions about passwords, and misinformation about passwords has spread like wildfire, often leading to people undermining their own security with poor password practices, sometimes even done in the name of improving cybersecurity.

In this chapter, you discover some best practices vis-à-vis passwords. These practices should help you both maximize your own security and maintain reasonable ease of use.

Passwords: The Primary Form of Authentication

Password authentication refers to the process of verifying the identity of users (whether human or computer process) by asking users to supply a password — that is, a previously-agreed-upon secret piece of information — that ostensibly the party authenticating would only know if they were truly the party who it claimed to be. While the term “password” implies that the information consists of a single word, today’s passwords can include combinations of characters that don’t form words in any spoken or written language.

Despite the availability for decades of many other authentication approaches and technologies — many of which offer significant advantages over passwords — passwords remain de facto worldwide standard for authenticating people online. Repeated predictions of the demise of passwords have been proven untrue, and the number of passwords in use grows every day.

Because password authentication is so common and because so many data breaches have resulted in the compromise of password databases, the topic has received significant media attention, with reports often spreading various misleading information. Gaining a proper understanding of the realm of passwords is important if you want to be cybersecure.

Avoiding Simplistic Passwords

Passwords only secure systems if unauthorized parties can’t easily guess them, or obtain them from other sources. Criminals often guess or otherwise obtain passwords by

- Guessing common passwords: It’s not a secret that 123456 and password are common passwords — data from recent breaches reveals that they are, in fact, among the most common passwords used on many systems (see the nearby sidebar)! Criminals exploit such sad reality and often attempt to breach accounts by using automated tools that feed systems passwords one at a time from lists of common passwords — and record when they have a hit. Sadly, those hits are often quite numerous.

- Launching dictionary attacks: Because many people choose to use actual English words as passwords, some automated hacker tools simply feed all the words in the dictionary to a system one at a time. As with lists of common passwords, such attacks often achieve numerous hits.

- Using people’s own information: Sadly, many people use their own names or birthdays as passwords. It is quite simple for criminals to attempt to use such information as passwords.

- Credential stuffing: Credential stuffing refers to when attackers take lists of usernames and passwords from one site — for example, from a site that was breached and whose username password database was subsequently posted online — and feed its entries to another system one at a time in order to see whether any of the login credentials from the first system work on the second. Because many people reuse username and password combinations between systems, credential stuffing is, generally speaking, quite effective.

Password Considerations

When you create passwords, keep in mind that, contrary to what you may have often heard from “experts,” more complex isn’t always better. Password strength should depend on how sensitive the data and system are that the password protects. The following sections discuss easily guessable passwords, complicated passwords, sensitive passwords, and password managers.

Easily guessable personal passwords

As alluded to earlier, criminals know that many people use the name or birth date of their significant other or pet as a password, so crooks often look at social media profiles and do Google searches in order to find likely passwords. They also use automated tools to feed lists of common names to targeted systems one by one, while watching to see whether the system being attacked accepts any of the names as a correct password.

Criminals who launch targeted attacks can exploit the vulnerability created by such personalized, yet easily guessable, passwords. However, the problem is much larger: Sometimes, reconnaissance is done through automated means — so, even opportunistic attackers can leverage such an approach.

Furthermore, because, by definition, a significant percentage of people have common names, the automated feeders of common names often achieve a significant number of hits.

Complicated passwords aren’t always better

To address the problems inherent in weak passwords, many experts recommend using long, complex passwords — for example, containing both uppercase and lowercase letters, as well as numbers and special characters.

Using such passwords makes sense in theory, and if such a scheme is utilized to secure access to a small number of sensitive systems, it can work quite well. However, employing such a model for a larger number of passwords is likely to lead to problems that can undermine security:

- Inappropriately reusing passwords

- Writing down passwords in insecure locations

- Selecting passwords with poor randomization and formatted using predictable patterns, such as using a capital for the first letter of a complicated password, followed by all lowercase characters, and then a number

Hence, in the real world, from a practical perspective, because the human mind can’t remember many complex passwords, using significant numbers of complex passwords can create serious security risks.

According to The Wall Street Journal, Bill Burr, the author of NIST Special Publication 800-63 Appendix A (which discusses password complexity requirements), admitted shortly before the turn of the new decade that password complexity has failed in practice. He now recommends using passphrases, and not complex passwords, for authentication.

Passphrases are passwords consisting of entire phrases or phrase-length strings of characters, rather than of simply a word or a word-length group of characters. Sometimes passphrases even consist of complete sentences. Think of passphrases as long (usually at least 25 characters) but relatively easy to remember passwords.

Different levels of sensitivity

Not all types of data require the same level of password protection. For example, the government doesn’t protect its unclassified systems the same way that it secures its top-secret information and infrastructure. In your mind or on paper, classify the systems for which you need secure access. Then informally classify the systems that you access and establish your own informal password policies accordingly.

On the basis of risk levels, feel free to employ different password strategies. Random passwords, passwords composed of multiple words possibly separated with numbers, passphrases, and even simple passwords each have their appropriate uses. Of course, multifactor authentication can, and should, help augment security when it’s both appropriate and available.

Your most sensitive passwords may not be the ones you think

When classifying your passwords, keep in mind that while people often believe that their online banking and other financial system passwords are their most sensitive passwords, that is not always the case. Because many modern online systems allow people to reset their passwords after validating their identities through email messages sent to their previously known email addresses, criminals who gain access to someone’s email account may be able to do a lot more than just read email without authorization: They may be able to reset that user’s passwords to many systems, including to some financial institutions.

Likewise, many sites leverage social-media-based authentication capabilities — especially those provided by Facebook and Twitter — so a compromised password on a social media platform can lead to unauthorized parties gaining access to other systems as well, some of which may be quite a bit more sensitive in nature than a site on which you just share pictures.

You can reuse passwords — sometimes

You may be surprised to read the following statement in a book teaching you how to stay cybersecure:

You don’t need to use strong passwords for accounts that you create solely because a website requires a login, but that does not, from your perspective, protect anything of value.

If you create an account in order to access free resources, for example, and you have nothing whatsoever of value stored within the account, and you don’t mind getting a new account the next time you log in, you can even use a weak password — and use it again for other similar sites.

Consider using a password manager

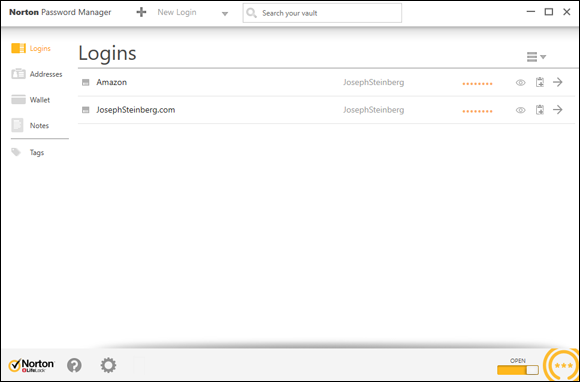

Alternatively, you can use a password manager tool, shown in Figure 8-1, to securely store your passwords. Password managers are software that help people manage passwords by generating, storing, and retrieving complex passwords. Password managers typically store all their data in encrypted formats and provide access to users only after authenticating them with either a strong password or multifactor authentication.

FIGURE 8-1: A password manager.

Many password managers are on the market. While all modern mainstream password managers utilize encryption to protect the sensitive data that they store, some store passwords locally (for example, in a database on your phone), while others store them in the cloud.

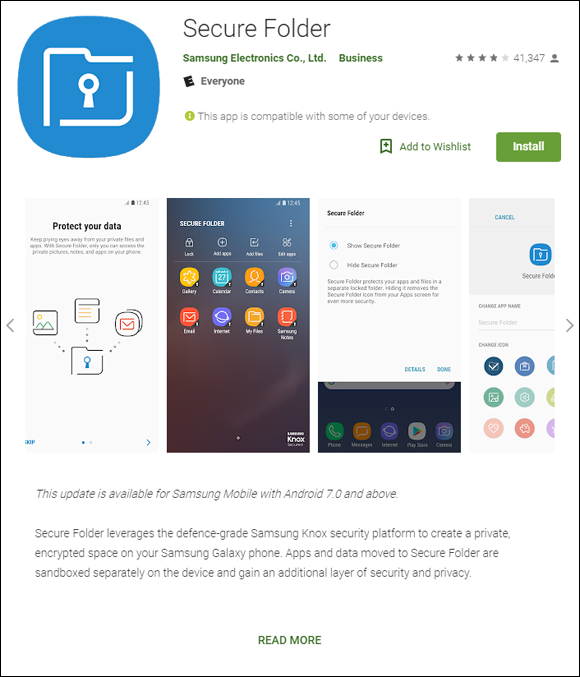

Many modern smartphones come equipped with a so-called secure area — a private, encrypted space that is sandboxed, or separated, into its own running environment. Ideally, any password information stored on a mobile device should be stored protected in the secure area (see Figure 8-2).

FIGURE 8-2: Secure Folder, the secure area app provided by Samsung for its Android series of phones, as seen in the Google Play Store.

Data that is stored in the secure area is supposed to be rendered by the operating system to be inaccessible to a user unless that user enters the secure area, which usually requires running a secure area app and entering a special password or otherwise authenticating. Devices also typically display some special symbol somewhere on the screen when a user is working with data or an app located in the secure area.

Creating Memorable, Strong Passwords

The following list offers suggestions that may help you create strong passwords that are, for most people, far easier to remember than a seemingly random, unintelligible mix of letters, numbers, and symbols:

- Combine three or more unrelated words and proper nouns, with numbers separating them. For example, laptop2william7cows is far easier to remember than 6ytBgv%j8P. In general, the longer the words you use within the password, the stronger the resulting password will be.

- If you must use a special character, add a special character before each number; you can even use the same character for all your passwords. (If you use the same passwords as in the previous example and follow this advice, the passwords is laptop%2william%7cows.) In theory, reusing the same character may not be the best way to do things from a security standpoint, but doing so makes memorization much easier, and the security should still be good enough for purposes for which a password is suitable on its own anyway.

- Ideally, use at least one non-English word or proper name. Choose a word or name that is familiar to you but that others are unlikely to guess. Don’t use the name of your significant other, best friend, or pet.

- If you must use both capital and lowercase letters (or want to make your password even stronger), use capitals that always appear in a particular location throughout all your strong passwords. Make sure, though, that you don’t put them at the start of words because that location is where most people put them. For example, if you know that you always capitalize the second and third letter of the last word, then laptop2william7kALb isn’t harder to remember than laptop2william7kalb.

Knowing When to Change Passwords

Conventional wisdom — as you have likely heard many times — is that it is ideal to change your password quite frequently. The American Association of Retired Persons (AARP), for example, until recently recommended on its website that people (including the disproportionately older folks who comprise its membership) “change critical passwords frequently, possibly every other week.”

Theoretically, such an approach is correct — frequent changes reduce risks in several ways — but in reality, it’s bad advice that you shouldn’t follow.

If you have a bank account, mortgage, a couple credit cards, a phone bill, a high-speed Internet bill, utility bills, social media accounts, email accounts, and so on, you may easily be talking about a dozen or so critical passwords. Changing them every two weeks would mean 312 new critical passwords to remember within the span of every year — and you likely have many more passwords on top of that figure. For many people, changing important passwords every two weeks may mean learning a hundred new passwords every month.

Unless you have a phenomenal, photographic memory, how likely is it that you’ll remember all such passwords? Or will you simply make your passwords weaker in order to facilitate remembering them after frequent changes?

The bottom line is that changing passwords often makes remembering them far more difficult, increasing the odds that you’ll write them down and store them insecurely, select weaker passwords, and/or set your new passwords to be the same as old passwords with minute changes (for example, password2 to replace password1).

Of course, if you use a password manager that can reset passwords, you can configure it to reset them often. In fact, I’ve worked with a commercial password-management system used for protecting system administration access to sensitive financial systems that automatically reset administrators’ passwords every time they logged on.

Changing Passwords after a Breach

If you receive notification from a business, organization, or government entity that it has suffered a security breach and that you should change your password, follow these tips:

- Don’t click any links in the message because most such messages are scams.

- Visit the organization’s website and official social media accounts to verify that such an announcement was actually made.

- Pay attention to news stories to see whether reliable, mainstream media is reporting such a breach.

- If the story checks out, go to the organization’s website and make the change.

Ignore experts who “cry wolf” and tell you to change all your passwords after every single breach as a matter of “extra caution” or that it may not be necessary to change passwords, but that “it is better to be safe than sorry.” If changing passwords is not necessary, doing so uses up your brainpower, time, and energy, and, whether you realize it or not, likely dissuades you from changing passwords if a situation arises in which you actually do need to make such changes.

After all, if after a breach you make unnecessary password changes and then find out that your friends who did not do so fared no worse than you, you may grow weary and ignore future warnings to change your password when doing so is actually necessary.

If you reuse passwords on sites where the passwords matter — which you should not be doing — and a password that is compromised somewhere is also used on other sites, be sure to change it at the other sites as well. In such a case, also take the opportunity when resetting passwords to switch to unique passwords for each of the sites.

Providing Passwords to Humans

On its website, the United States Federal Trade Commission (FTC) recommends the following:

Don’t share passwords on the phone, in texts, or by email. Legitimate companies will not send you messages asking for your password.

That sounds like good advice, and it would be, if it were not for one important fact: Legitimate businesses do ask you for passwords over the phone! So how do you know when it is safe to provide your password and when it is not?

Should you just check your caller ID? No. The sad reality is that crooks spoof caller IDs on a regular basis.

What you should do is never provide any sensitive information — including passwords, of course — over the phone unless you initiated the call with the party requesting the password and are sure that you called the legitimate party. It is far less risky, for example, to provide an account’s phone-access password to a customer service representative who asks for it during a conversation initiated by you calling to the bank using the number printed on your ATM card than if someone calls you claiming to be from your bank and requests the same private information in order to “verify your identity.”

Storing Passwords

Ideally, don’t write down your passwords to sensitive systems or store them anywhere other than in your brain.

Storing passwords for your heirs

If you want to ensure that you have a copy of your most sensitive passwords (and perhaps any other passwords) written down somewhere — perhaps for your family in case something happens to you — write the passwords down and put the list in a safe deposit box or safe, and do not take the list out on a regular basis. Of course, if you want the list to be useful to your heirs, make sure to keep the list updated.

Some major technology providers, such as Facebook and Apple, also provide people with the ability to specify who should be given access to their accounts upon their deaths.

Storing general passwords

For less sensitive passwords, use a password manager or store them in an encrypted form on a strongly-secured computer or device. If you store your passwords on a phone, use the secure area. (For more on password managers and your phone’s secure area, see the section “Consider using a password manager,” earlier in this chapter.)

Transmitting Passwords

Theoretically, you should never email or text someone a password. So, what should you do ifyour child texts you from school saying that they forgot the password to their email, or the like?

Obviously, none of these methods are ideal ways to transmit passwords, but they certainly are better options than what so many people do, which is to simply text or email people passwords in clear text.

Discovering Alternatives to Passwords

On some occasions, you should take advantage of alternatives to password authentication. While there are many ways to authenticate people, a modern user is likely to encounter certain types:

- Biometric authentication

- SMS-based authentication

- App-based one-time passwords

- Hardware token authentication

- USB-based authentication

Biometric authentication

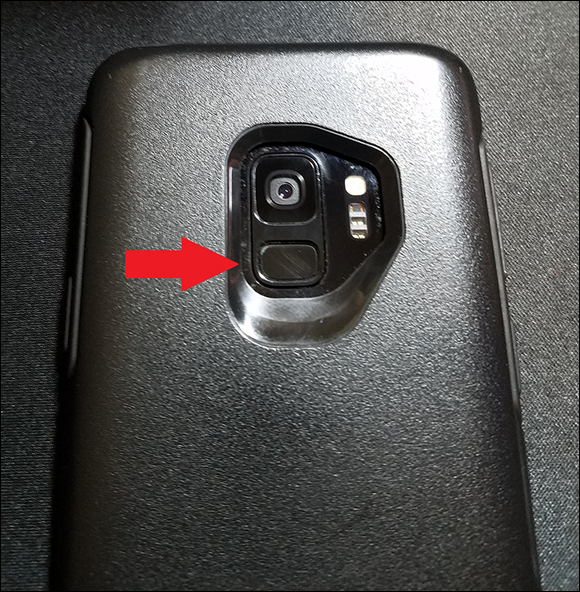

Biometric authentication refers to authenticating using some unique identifier of your physical person — for example, your fingerprint. Using biometrics — especially in combination with a password — can be a strong method of authentication, and it certainly has its place. Two popular forms used in the consumer market are fingerprints and iris-based authentication.

While using a fingerprint to unlock a phone is certainly convenient, and looking at the screen is even more convenient, in many cases, mandating that phones be unlocked only after a user provides a strong password actually provides better security.

Before using biometric authentication, consider the following points:

- Your fingerprints are likely all over your phone. You hold your phone with your fingers. How hard would it be for criminals who steal the phone to lift your prints and unlock the phone if you enable fingerprint based authentication using a phone’s built-in fingerprint reader (see Figure 8-3)? If anything sensitive is on the device, it may be at risk. No, the average crook looking to make a quick buck selling your phone is unlikely to spend the time to unlock it — the crook will more than likely just wipe it — but if someone wants the data on your phone for whatever reason, and you used fingerprints to secure your device, you may have a serious problem on your hands (pun intended).

- If your biometric information is captured, you can’t reset it as you can a password. Do you fully trust the parties to whom you’re giving this information to properly protect it?

- If your biometric information is on your phone or computer, what happens if malware somehow infects your device? What happens if a server where you stored the same information is breached? Are you positive that all the data is properly encrypted and that the software on your device fully defended your biometric data from capture?

FIGURE 8-3: A phone fingerprint sensor on a Samsung Galaxy S9 in an Otterbox case. Some phones have the reader on the front, while others, like the S9, have it on the back.

- Masks create problems for facial recognition systems. Most facial recognition systems will not work if a person is wearing a mask, as was required in many places during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Cold weather creates problems. Fingerprints can’t be read even through smartphone-compatible gloves.

- Glasses, as worn by millions of people, pose challenges to iris scanners. Some iris readers require users to take off their glasses in order to authenticate. If you use such authentication to secure a phone, you may have difficulty unlocking your phone when you’re outdoors on a sunny day.

- Biometrics can undermine your rights. If, for some reason, law enforcement wants to access the data on your biometric-protected phone or other computer system, it may be able to force you to provide your biometric authentication, even in countries like the United States where you have the right to remain silent and not provide a password. Likewise, the government may be able to obtain a warrant to collect your biometric data, which, unlike a password, you can’t reset. Even if the data proves you innocent of whatever the government suspects you have done wrong, do you trust the government to properly secure the data over the long term? (These types of issues are in the process of being addressed by various courts, and the final results may vary by jurisdiction.)

- Impersonation is possible. Some quasi-biometric authentication, such as the face recognition on some devices, can be tricked into believing that a person is present by playing to them a high-definition video of that person.

- Voice-based authentication is no longer trustworthy. It has become possible for criminals to undermine voice-based authentication using what has become known as deep fake technology, which is technology that uses artificial intelligence to impersonate a person either in an audio recording or video recording. Criminals have already successfully stolen money using deep-faked audio.

As such, biometrics have their place. Using a fingerprint to unlock features on your phone is certainly convenient but think before you proceed. Be certain that in your case the benefits outweigh the drawbacks.

SMS-based authentication

In SMS (text message)-based authentication, a code is sent to your cellphone. You then enter that code into a web or app to prove your identity. This type of authentication is, in itself, not considered secure enough for authentication when true multifactor authentication in required. Sophisticated criminals have ways of intercepting such passwords, and can sometimes even social-engineer phone companies in order to steal people’s phone numbers, thereby, stealing their SMS messages. That said, SMS one-time passwords used in combination with a strong password are typically better than just using the password.

App-based one-time passwords

One-time passwords generated with an app running on a phone or computer are a good addition to strong passwords, but they should not be used on their own. App-based one-time passwords are likely a more secure way to authenticate than SMS-based one-time passwords (see preceding section), but they can be inconvenient; if you get a new phone, for example, some one time password generation apps require you to reconfigure information at every one of the sites where you’re using one-time passwords created by the generator app running on your smartphone. Even those that do not may require you to disable password generation on your old device in addition to enabling it on the new one.

As with SMS-based one-time passwords, if you send an app-generated one-time password to a criminal’s phishing website instead of a legitimate site, the criminal can replay it to the corresponding real site in real time, undermining the security benefits of the one-time password in their entirety.

Hardware token authentication

Hardware tokens (see Figure 8-4) that generate new one-time passwords every x seconds are similar to the apps described in the preceding section with the major difference being that you need to carry a specialized device that generates the one-time codes. Some tokens can also function in other modes — for example, allowing for challenge-response types of authentication in which the site being logged into displays a challenge number that the user enters into the token in order to retrieve a corresponding response number that the user enters into the site in order to authenticate.

Although hardware token devices normally are more secure than one-time generator apps in that the former don’t run on devices that can be infected by malware or taken over by criminals remotely, they can be inconvenient. They are also prone to getting lost, and are less likely to be quickly detected as missing as are phones. Many models are also not waterproof, leading to problems of such devices sometimes getting destroyed when people do their laundry after forgetting the devices in their pockets.

FIGURE 8-4: An RSA SecureID brand one-time password generator hardware token.

USB-based authentication

USB devices that contain authentication information — for example, digital certificates — can strengthen authentication. Care must be exercised, however, to use such devices only in combination with trusted machines — you don’t want the device infected or destroyed by some rogue device, and you want to be sure that the machine obtaining the certificate, for example, doesn’t transmit it to an unauthorized party.

Many modern USB-based devices offer all sorts of defenses against such attacks. Of course, you can connect USB devices only to devices and apps that support USB-based authentication. You also must carry the device with you and ensure that it doesn’t get lost or damaged. And, as with other hardware keys, such devices are prone to being lost, and are not always waterproof.

Establishing a stronger password for online banking than for commenting on a blog on which you plan to comment only once in a blue moon makes sense. Likewise, your password to the blog should probably be stronger than the one used to access a free news site that requires you to log in but on which you never post anything and at which, if your account were compromised, the breach would have zero impact upon you.

Establishing a stronger password for online banking than for commenting on a blog on which you plan to comment only once in a blue moon makes sense. Likewise, your password to the blog should probably be stronger than the one used to access a free news site that requires you to log in but on which you never post anything and at which, if your account were compromised, the breach would have zero impact upon you. Such technology is appropriate for general passwords, but not for the most sensitive ones. Various password managers have been hacked, and if something does go wrong you could have a nightmare on your hands. Remember, when you store passwords in a password manager you are “putting multiple eggs into one basket,” and that password managers are also treasure chests for hackers and on their radars. As such, of course, be sure to properly secure any device that you use to access your password manager.

Such technology is appropriate for general passwords, but not for the most sensitive ones. Various password managers have been hacked, and if something does go wrong you could have a nightmare on your hands. Remember, when you store passwords in a password manager you are “putting multiple eggs into one basket,” and that password managers are also treasure chests for hackers and on their radars. As such, of course, be sure to properly secure any device that you use to access your password manager. Remember, though, that operating systems are not perfect, and sometimes bugs do create exploitable vulnerabilities. So even if you do trust the secure area, keep in mind that its security is not 100 percent guaranteed.

Remember, though, that operating systems are not perfect, and sometimes bugs do create exploitable vulnerabilities. So even if you do trust the secure area, keep in mind that its security is not 100 percent guaranteed.