There’s no disputing the fact that there is a key reason why many digital SLR buyers choose Nikon cameras: Nikon lenses. Some favor Nikon cameras because of the broad selection of quality lenses. Others already possess a large collection of Nikon optics (perhaps dating from the owner’s photography during the film era), and the ability to use those lenses on the latest digital cameras is a big plus. A few may be attracted to the Nikon brand because there are many inexpensive lenses (including a few in the $100 to $200 price range) that make it possible to assemble a basic kit for cameras like the D3400 without spending a lot of cash.

It’s true that there is a mind-bending assortment of high-quality lenses available to enhance the capabilities of Nikon cameras. In mid-2016, Nikon announced the production of its 100 millionth Nikkor lens. You can use thousands of current and older lenses introduced by Nikon and third-party vendors since 1959, although lenses made before 1977 may need an inexpensive modification for use with cameras other than your D3400 or other cameras in the Nikon D5xxx series, D3xxx series, D60, D40, and D40x. (More on this later.) These lenses can give you a wider view, bring distant subjects closer, let you focus closer, shoot under lower light conditions, or provide a more detailed, sharper image for critical work. Other than the sensor itself, the lens you choose for your dSLR is the most important component in determining image quality and perspective of your images.

This chapter explains how to select the best lenses for the kinds of photography you want to do.

Sensor Sensibilities

From time to time, you’ve heard the term crop factor, and you’ve probably also heard the term lens multiplier factor. Both are misleading and inaccurate terms used to describe the same phenomenon: the fact that cameras like the D3400 (and most other affordable digital SLRs) provide a field of view that’s smaller and narrower than that produced by certain other (usually much more expensive) cameras, when fitted with exactly the same lens.

Figure 10.1 quite clearly shows the phenomenon at work. The outer rectangle, marked 1X, shows the field of view you might expect with a 28mm lens mounted on one of Nikon’s “full-frame” (non-cropped) cameras, like the Nikon D5, D810, D750, D610, Df, and earlier full-frame cameras. The area marked 1.5X shows the field of view you’d get with that 28mm lens installed on a D3400. It’s easy to see from the illustration that the 1X rendition provides a wider, more expansive view, while the inner field of view is, in comparison, cropped.

The cropping effect is produced because the sensors of DX cameras like the Nikon D3400 are smaller than the sensors of the Nikon full-frame, or FX, cameras. The “full-frame” camera has a sensor that’s the size of the standard 35mm film frame, roughly 24mm × 36mm. Your D3400’s sensor does not measure 24mm × 36mm; instead, it specs out at 23.5mm × 15.6mm, or about 66.7 percent of the area of a full-frame sensor, as shown by the boxes in the figure. You can calculate the relative field of view by dividing the focal length of the lens by .667. Thus, a 100mm lens mounted on a D3400 has the same field of view as a 150mm lens on the Nikon D800. We humans tend to perform multiplication operations in our heads more easily than division, so such field of view comparisons are usually calculated using the reciprocal of .667—1.5—so we can multiply instead. (100 / .667 = 150; 100 × 1.5 = 150.)

Figure 10.1 Nikon offers digital SLRs with full-frame (1X) crops, as well as 1.5X crops.

This translation is generally useful only if you’re accustomed to using full-frame cameras (usually of the film variety) and want to know how a familiar lens will perform on a digital camera. I strongly prefer crop factor over lens multiplier, because nothing is being multiplied; a 100mm lens doesn’t “become” a 150mm lens—the depth-of-field and lens aperture remain the same. (I’ll explain more about these later in this chapter.) Only the field of view is cropped. But crop factor isn’t much better, as it implies that the 24mm × 36mm frame is “full” and anything else is “less.” I get e-mails all the time from photographers who point out that they own full-frame cameras with 36mm × 48mm sensors (like the Mamiya 645ZD or Hasselblad H3D-39 medium-format digitals). By their reckoning, the “half-size” sensors found in cameras like the Nikon D800 and D4 are “cropped.”

If you’re accustomed to using full-frame film cameras, you might find it helpful to use the crop factor “multiplier” to translate a lens’s real focal length into the full-frame equivalent, even though, as I said, nothing is actually being multiplied. Throughout most of this book, I’ve been using actual focal lengths and not equivalents, except when referring to specific wide-angle or telephoto focal length ranges and their fields of view.

Crop or Not?

There’s a lot of debate over the “advantages” and “disadvantages” of using a camera with a “cropped” sensor, versus one with a “full-frame” sensor. The arguments go like this:

- “Free” 1.5X teleconverter. The Nikon D3400 (and other cameras with the 1.5X crop factor), magically transform any telephoto lens you have into a longer lens, which can be useful for sports, wildlife photography, and other endeavors that benefit from more reach. Yet, your f/stop remains the same (that is, a 300mm f/4 becomes a very fast 450mm f/4 lens). Some discount this advantage, pointing out that the exact same field of view can be had by taking a full-frame image, and trimming it to the 1.5X equivalent. While that is strictly true, it doesn’t take into account a factor called pixel density.

- Dense pixels = more noise. The other side of the pixel density coin is that the denser packing of pixels to achieve 24 megapixels in the D3400 sensor means that each pixel must be smaller, and will have less light-gathering capabilities. Larger pixels capture light more efficiently, reducing the need to amplify the signal when boosting ISO sensitivity, and, therefore, producing less noise. In an absolute sense, this is true, and cameras like the top-of-the-line D5 and retro Df do have sensational high ISO performance. However, the D3400’s sensor is improved over earlier cameras, so you’ll find it performs very well at higher ISOs.

- Lack of wide-angle perspective. Of course, the 1.5X “crop” factor applies to wide-angle lenses, too, so your 20mm ultra-wide lens becomes a hum-drum 30mm near-wide-angle, and a 35mm focal length is transformed into what photographers call a “normal” lens. Zoom lenses, like the 18-140mm lens that is often purchased with the Nikon D3400 in a kit, have less wide-angle perspective at its minimum focal length. The 18-55mm kit lens, for example, is the equivalent of a 27mm moderate wide angle when zoomed to its widest setting. Nikon has “fixed” this problem by providing several different extra-wide zooms specifically for the DX format, including the (relatively) affordable 12-24mm and 10-24mm DX Nikkors. You’ll never really lack for wide-angle lenses, but some of us will need to buy wider optics to regain the expansive view we’re looking for.

- Mixed body mix-up. The relatively small number of Nikon D3400 owners who also have a Nikon full-frame camera like the D610 can’t ignore the focal-length mix-up factor. If you own both FX- and DX-format cameras (some D3400 owners use them as a backup to a D610, for example), it’s vexing to have to adjust to the different fields of view that the cameras provide. If you remove a given lens from one camera and put it on the other, the effective focal length/ field of view changes. That 16-35mm zoom works as an ultra-wide to wide angle on a D610, but functions more as a moderate wide-angle to normal lens on a D3400. To get the “look” on both cameras, you’d need to use a 12-24mm zoom on the D3400, and the 17-35mm zoom on the D610. It’s possible to become accustomed to this field of view shake-up and, indeed, some photographers put it to work by mounting their longest telephoto lens on the D3400 and their wide-angle lenses on their full-frame camera. Even if you’ve never owned both an FX and a DX camera, you should be aware of the possible confusion.

Your First Lens

Some Nikon dSLRs are almost always purchased with a lens. The entry- and mid-level Nikon dSLRs, including the Nikon D3400, are often bought by those new to digital photography, frequently by first-time SLR or dSLR owners who find the recent AF-S DX Nikkor 18-140mm f/3.5-5.6G ED VR, older AF-S DX Nikkor 18-105mm f/3.5-5.6G ED VR, or new AF-P DX Nikkor 18-55mm f/3.5-5.6G VR collapsible lens (all shown in Figure 10.2) irresistible bargains. All three have shake-canceling vibration reduction built in. Other Nikon models, including the Nikon D5, Df, and D810, are generally purchased without a lens by veteran Nikon photographers who already have a complement of optics to use with their cameras.

I bought my D3400 with the new kit lens. Nikon has been known to sell only kit packages of its entry- and mid-level cameras initially, and offer bodies only at some later date. Depending on which category of photographer you fall into, you’ll need to make a decision about what kit lens to buy, or decide what other kind of lenses you need to fill out your complement of Nikon optics. This section will cover “first lens” concerns, while later in the chapter we’ll look at “add-on lens” considerations.

When deciding on a first lens, there are several factors you’ll want to consider:

- Cost. You might have stretched your budget a bit to purchase your Nikon D3400, so the AF-P 18-55mm VR kit lens helps you keep the cost of your first lens fairly low. In a kit, this lens may tack on just $100 to the price of the body alone. In addition, there are excellent moderately priced lenses available that will add from $100 to $500 to the price of your camera if purchased at the same time.

- Zoom range. If you have only one lens, you’ll want a fairly long zoom range to provide as much flexibility as possible. Fortunately, several popular basic lenses for the D3400 have 3X to 7.8X zoom ranges (I’ll list some of them next), extending from moderate wide-angle/normal out to medium telephoto. These are all fine for everyday shooting, portraits, and some types of sports.

- Adequate maximum aperture. You’ll want an f/stop of at least f/3.5 to f/4 for shooting under fairly low light conditions. The thing to watch for is the maximum aperture when the lens is zoomed to its telephoto end. You may end up with no better than an f/5.6 maximum aperture. That’s not great, but you can often live with it, particularly with a lens having vibration reduction (VR) capabilities, because you can often shoot at lower shutter speeds to compensate for the limited maximum aperture.

- Image quality. Your starter lens should have good image quality, because that’s one of the primary factors that will be used to judge your photos. Even at a low price, several of the different lenses that can be used with the D3400 kit (such as the 18-140mm zoom) include extra-low dispersion glass and aspherical elements that minimize distortion and chromatic aberration; they are sharp enough for most applications. If you read the user evaluations in the online photography forums, you know that owners of the kit lenses have been very pleased with their image quality.

- Size matters. A good walking-around lens is compact in size and light in weight.

- Fast autofocusing. Your first lens should have a speedy autofocus system, such as the Silent Wave motor found in Nikon AF-S lenses, and fast, extra-quiet stepping motor included in the new AF-P lenses. As you’ll learn later, lenses used on the D3400 must have the AF-S or AF-P designation (which means that the lens itself contains an internal autofocusing motor) if you want automatic focus. (Many—but not all—third-party lenses also have internal focus motors.)

- Close focusing. The ability to focus down to 12 inches or closer will let you use your basic lens for some types of macro photography.

You can find comparisons of the lenses discussed in the next section, as well as evaluations of lenses I don’t describe, third-party optics from Sigma, Tokina, Tamron, and other vendors, in online groups and websites.

Buy Now, Expand Later

As I noted earlier, when the Nikon D3400 was introduced, it was available both in kit form with the 18-140mm VR lens and in body-only packaging. The following optics are all good, basic lenses that can serve you well as a “walk-around” lens (one you keep on the camera most of the time, especially when you’re out and about without your camera bag). The number of options available to you is actually quite amazing, even if your budget is limited to about $100 to $350 for your first lens. Here’s a list of Nikon’s best-bet “first” lenses. Don’t worry about sorting out the alphabet soup right now; I provide a complete list of Nikon lens “codes” later in the chapter.

- AF-S DX Nikkor 18-105mm f/3.5-5.6G ED VR. If you want a step-up from the kit lens at an affordable price, this older lens is a reasonable choice as a “walking-around” lens for this camera. I much prefer it over the 18-200mm VR (described later), even though it has a more limited zoom range. Its focal length range is quite sufficient for most general photography, and at around $400 with the camera, it’s a real bargain (see Figure 10.2, left).

- AF-S DX NIKKOR 18-140mm f/3.5-5.6G ED VR. This is the newest Nikon DX kit lens, offering an extended 7.8X zoom range, a minimum focus distance of roughly 18 inches, and manual focus override that allows you to fine-tune focus after the D3400 has set basic focus automatically. (That feature is especially useful when shooting macro images or working with selective focus techniques when you might want to select a focus point that’s slightly different from what the camera selects.) Its $500 price may be a stretch for the buyer of an entry-level camera like the D3400, but it is a versatile performer. (See Figure 10.2, center.)

Figure 10.2 The AF-S DX Nikkor 18-105mm f/3.5-5.6G ED VR(left), AF-S DX Nikkor 18-140mm f/3.5-5.6G ED VR (center), and AF-P DX Nikkor 18-55mm f/3.5-5.6G VR (right).

- AF-P DX Nikkor 18-55mm f/3.5-5.6G VR. Nikon actually offers two versions of this AF-P supercompact collapsible lens, plus a third AF-S version with the older Silent Wave motor instead of the AF-P’s extra-quiet stepping motor. Other than the AF motor, the only difference among them is that one of the AF-P lenses lacks the vibration reduction (VR) anti-shake feature. Neither of the AF-P lenses is available for purchase separately as I write this, nor is the D3400 available in a body-only configuration, so it’s difficult to set a price for the lens alone. You can expect the non-VR lens to reduce your kit cost by about $50, and, I expect some vendors will manage to package the camera with the AF-S lens and knock an additional $50 off. However, the vibration reduction partially offsets the relatively slow maximum aperture of the lens at the telephoto position. (See Figure 10.2, right.)

- AF-S DX Nikkor AF-S DX 16-80mm f/2.8-4E ED VR. Those who plan to upgrade to a more upscale DX camera in the future, such as the Nikon D500, or who already own another DX camera, such as the D7200 might not consider this excellent lens an extravagance. However, it is a roughly $1,100 optic, and a significant upgrade from the 16-85mm lens it replaced (described next). However, it is definitely a financial stretch for the typical D3400 owner, and I’m mentioning it only for completeness.

- AF-S DX Nikkor 16-85mm f/3.5-5.6G ED VR. The 16-85mm VR lens is the zoom that would make a lot of sense as a kit lens if there weren’t better choices available. It’s still available new for about $700, but I expect it will probably be discontinued soon, as the 16-80mm lens described above effectively provides a (more expensive) replacement. If you really want to use just a single lens with your camera, this one provides an excellent combination of focal lengths, image quality, and features. Its zoom range extends from a true wide angle (equivalent to a 24mm lens on a full-frame camera) to a useful medium telephoto (about 128mm equivalent), and so can be used for everything from architecture to portraiture to sports. If you think vibration reduction is useful only with longer telephoto lenses, you may be surprised at how much it helps you hand-hold your D3400 even at the widest focal lengths. The only disadvantage to this lens is its relatively slow speed (f/5.6) when you crank it out to the telephoto end.

- AF-S DX Zoom-Nikkor 18-70mm f/3.5-4.5G IF-ED. If you don’t plan on getting a longer zoom-range basic lens, I highly recommend this aging, but impressive lens, if you can find one in stock as a used item. Originally introduced as the kit lens for the venerable Nikon D70, the 18-70mm zoom quickly gained a reputation as a very sharp lens at a bargain price. It doesn’t provide a view that’s as long or as wide as the 16-85, but it’s a half-stop faster at its maximum zoom position. You may have to hunt around to find one of these, but they are available for $120 to $150 and well worth it. I own one to this day, and use it regularly, although it spends most of its time installed on my D3200, which has been converted to infrared-only photography.

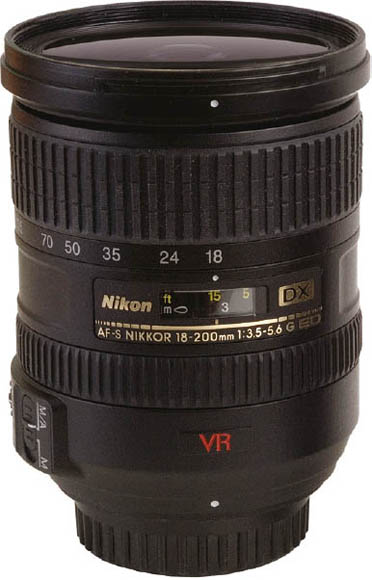

- AF-S DX VR II Zoom-Nikkor 18-200mm f/3.5-5.6G IF-ED. I owned this lens for about three months, and decided it really didn’t meet my needs. It was introduced as an ideal “kit” lens for the Nikon D200 a few years back, and, at the time had almost everything you might want. It’s a holdover, more upscale kit lens for the D3400. Its stunning 11X zoom range covers everything from the equivalent of 27mm to 300mm when the 1.5X crop factor is figured in, and its VR capabilities plus light weight let you use it without a tripod most of the time. However, I found the image quality to be good, but not outstanding, and the slow maximum aperture at 200mm to be limiting when a fast shutter speed is required to stop action. The “zoom creep” (a tendency for the lens to zoom when the camera is tilted up or down) found in many examples will drive you nuts after a while (see Figure 10.3). Fortunately, the new $650 version with improved VR and with the creep fixed has been available for some time.

- AF-S VR Zoom-Nikkor 24-85mm f/3.5-4.5G. Priced at about $500, this lens is reasonably priced, and has the advantage (like the 24-120mm lens) of being a full-frame optic, so if you upgrade in the future to a Nikon FX camera, you can take this one along with you. I happen to own both this lens and Nikon’s much more expensive 24-70mm f/2.8 optic, and tend to use this one (which costs about one-third as much) much more often. It’s not as fast at its maximum zoom setting, but offers a bit more reach, vibration reduction, and is much more compact. This is an excellent walk-around lens for the D3400 if you don’t need the extra-wide 18-23mm focal lengths. (See Figure 10.4, left.)

- AF-S VR Zoom-Nikkor 24-120mm f/4G ED VR. This one is a relatively new full-frame lens, expensive at about $1,100, but it works fine on a cropped sensor model like the D3400. It has a useful zoom range, and, as a bonus, if you ever decide to upgrade to a full-frame camera, you can take this lens along with you.

Figure 10.3 The AF-S DX VR II Zoom-Nikkor 18-200mm f/3.5-5.6G IF-ED is a lightweight “walking-around” lens.

Figure 10.4 This AF-S VR Zoom-Nikkor 24-85mm f/3.5-4.5G lens (left) is affordable, and is compatible with full-frame cameras, too. Right: Nikon’s versatile 18-300mm f/3.5-5.6 ED VR zoom lens.

When you’re ready to expand your DX lens collection, the following lenses are some of your best-bet options.

- AF-S DX Nikkor 12-24 f/4G IF-ED. This $1,150 lens was the original wide zoom for DX cameras, and is great for those who want a fast, constant f/4 maximum aperture and don’t need an ultra-wide view. It’s still available new, as an extra-cost option with a more rugged build, and a front thread that accepts “professional” 77mm filters.

- AF-S DX Nikkor 10-24mm f/3.5-4.5G ED. If you need a wider view and lower price, this newer lens, at $900, is the most popular Nikon ultra-wide lens for the D3400. It focuses nearly three inches closer than its older sibling.

- AF-S DX Nikkor 35mm f/1.8G. If you want a fast, inexpensive “normal” lens for your D3400 for street photography, interiors, photojournalism, or indoor sports, this $200 lens fills the bill.

- AF-S DX Micro-Nikkor 40mm f/2.8G. This lens and the 85mm optic described next make up Nikon’s reasonably priced macro lens lineup. This one is just $280 and does an excellent job. I describe Nikon’s broader range of full-frame macro lenses at the end of this chapter.

- AF-S DX Micro-Nikkor 85mm f/3.5G ED VR. A bit more expensive at about $530, this longer Micro-Nikkor gives you a bit more distance from skittish subjects (like insects) and has vibration reduction so you can often shoot nature close-ups hand-held. Keep in mind that VR won’t freeze fronds swaying in the breeze; you’ll still need to use higher shutter speeds on windy days.

- AF-S DX Nikkor 17-55 f/2.8G IF-ED. This was the first “pro” lens for DX format and remains a popular, if expensive (at around $1,500) option. Personally, if I didn’t need a fast f/2.8 constant maximum aperture, I’d prefer to spend those bucks on a similar full-frame lens, like the 24-120mm f/4, which has VR to boot.

- AF-S DX Nikkor 55-300mm f/4.5-5.6G VR. For the price, this is an excellent lens in the short telephoto to supertelephoto range. Its $400 price tag won’t deplete your pocketbook as much as Nikon’s 18-300mm lens if you don’t need the wide-angle focal lengths. It’s a better performer at the telephoto lens, as well.

- AF-S DX Nikkor 55-200mm f/4-5.6G ED VRII / AF-S DX Nikkor 55-200mm f4.5-5.6 IF-ED VR. Nikon offers two lenses in the 55-200mm focal length range; a newer version with upgraded VR at $350, and an older model with similar specs, but less advanced vibration reduction. If you can locate one, the latter lens can often be purchased new for around $200. It’s not as sharp as its upgraded sibling, but it can make a good addition to your camera bag until you can afford a deluxe version.

Your Best Do-Everything Option?

In mid-2012, Nikon introduced a DX lens at $999 that might actually be the best do-everything option for some D3400 shooters. The AF-S DX Nikkor 18-300mm f/3.5-5.6G ED VR zoom has an incredible 16.7X zoom range, yet is relatively light and compact, focuses close, and has image stabilization built in. (See Figure 10.4, right.) It’s become a standard walk-around lens on my DX-format cameras, because its 27-450mm equivalent focal length range is spectacular for sports and wildlife. It’s not my sharpest lens at its maximum focal length, but it more than makes up for a little softness at the far end with versatility.

- Ultra-long zoom range. Used on your D3400, this lens provides the equivalent field of view as a full-frame 27-400mm lens. That’s sort of wide to super telephoto, without the need to swap lenses. That versatility is important when shooting stills, of course, especially with sports and other rapidly changing scenes. But if you’re shooting movies, the 18-300mm focal lengths come in especially handy. You can capture a wide establishing shot to set the scene, switch to a medium shot to draw viewer attention to your main subjects, then capture an extreme close-up. Even if you’re collecting short clips, the action may be continuing between “takes,” so if you had to switch lenses you might miss something. Not so with this lens. You can change field of view between each shot as quickly as you can rotate the zoom ring. The lens’s long range has some possibilities for those mind-boggling quick zooms in or out during video capture, too. (Use with restraint!) The only drawback this lens has is that it is not especially sharp at its maximum telephoto setting. If most of your work requires 18-200mm focal lengths and you have an occasional need for the 200-300 range (and don’t want to shoot wide open), this lens can be very useful. However, sports and wildlife photographers who would use the longest focal lengths of this lens extensively would probably be better served by the AF-S VR Zoom-Nikkor 70-300mm f/4.5-5.6G IF-ED, which is about 1/3 less expensive, sharper at 300mm, and will work on full-frame cameras should you upgrade later on.

- Vibration reduction. It’s so common to have VR in telephoto lenses these days, especially those with equivalent or actual focal lengths of 400mm or more that you might not stop to think how rare image stabilization is at the other end. Among wide-angle lenses, Nikon’s 24-120mm f/4, 16-35mm f/4 full-frame, and new 24-85mm VR lenses (discussed later in this chapter) along with DX lenses (the three most common kit lenses, the 16-85mm f/3.5-5.6G, and the 18-300mm/18-200mm f/3.5-5.6) are it in the Nikon product line. While it’s arguable that VR is less essential in a wide-angle lens because camera shake blur is less of a problem, having a lens that starts wide and goes all the way to super telephoto with optical image stabilization built in is a definite plus.

- Compact size. Although it replaces a half-dozen or more lenses, the 18-300mm zoom measures just 3.3 × 4.7 inches and weighs 1 pound, 13 ounces, which is svelte for a 300mm lens (even if a bit large for an 18mm wide angle). However, it almost doubles in length when cranked out to its full 300mm setting, becoming lanky instead of svelte. Even so, in weight and size, your do-everything walk-around lens compares favorably to its 18-200mm predecessor (3 × 3.8, 1 pound, four ounces), takes pro-standard 77mm filters (vs. 72mm for the older model), and has a lock to totally prevent dreaded zoom creep, to boot. Mine doesn’t exhibit creep even with the lock off, however.

- Close focusing. The 18-300mm has the ability to focus down to 1.48 feet at 300mm, giving you a 1:3.2X maximum reproduction ratio (about one-third life-size in DX format). The 18-300mm is not a true macro lens, but when you’re venturing out with a single lens on your D3400, the ability to focus that closely at 300mm is the next best thing.

- Good (not great) image quality. Nikon says that three extra-low dispersion (ED) elements and three aspheric elements deliver the promised minimized chromatic aberration (which can be especially troublesome at wide-angle focal lengths), and the typical aberrations that appear when a lens is used at larger apertures (that’s something that will probably happen given the relatively slow f/5.6 maximum aperture at 300mm). Nikon touts this lens’s 9-bladed aperture for its pleasing bokeh, too. (I’ll show you the effects of bokeh later in this chapter.) As I said earlier, this lens delivers useful image quality even if it’s not the sharpest 300mm lens you can own.

What Lenses Can You Use?

The previous section helped you sort out what basic lens you need to buy with your Nikon D3400. Now, you’re probably wondering what lenses can be added to your growing collection (trust me, it will grow). You need to know which lenses are suitable and, most importantly, which lenses are fully compatible with your Nikon D3400.

With the Nikon D3400, the compatibility issue is a simple one: It can use any modern-era Nikon lens with the AF-S or AF-P designation, with full availability of all autofocus, auto aperture, auto-exposure, and image stabilization features (if present). Older lenses with the AF designation won’t autofocus on the D3400, but can still be used for automatic exposure. You can also use any Nikon AI, AI-S, or AI-P lens, which are manual focus lenses that were produced starting in 1977 and continue in production effectively through the present day, because Nikon continues to offer a limited number of manual focus lenses for those who need them. Just remember: AF-S—all features available; non-AF-S (including AF)—no autofocusing possible.

The Nikon D3400, as well as previous entry-level models in the D3xxx, D5xxx, D60, D40, and D40x series don’t have an autofocusing motor built into the camera body itself. The motor, present in all other Nikon digital SLRs, allows the camera to adjust the lens focus mechanically. Without that motor in the body, cameras like the D3400 must communicate focus information to the lens, so that the lens’s own built-in AF motor can take care of the autofocus process. Because virtually all newer Nikon-brand lenses are of the AF-S or AF-P type, this means your D3400 will have problems only with older Nikon optics.

That’s not true with third-party (non-Nikon) lenses. While your D3400 will accept virtually all modern lenses produced by Tokina, Tamron, Sigma, and other vendors, they will autofocus only with those lenses that contain an internal focusing motor, similar to Nikon’s AF-S offerings. Vendors have different designators to indicate these lenses, such as HSM (for hypersonic motor). You’ll have to check with the manufacturer of non-Nikon lenses to see if they are compatible with the D3400, particularly since some vendors have been gradually introducing revamped versions of their existing lenses with the addition of an internal motor.

There’s some good news for those using one of Nikon’s focus-motorless entry-level models. These cameras, unlike Nikon models that have the camera body focus motor, can safely use lenses offered prior to 1977 (although I expect that, while numerous, most of these aren’t used much by those who have modern digital cameras). That’s because cameras other than Nikon’s entry-level quartet have a pin on the lens mount that can be damaged by an older, unmodified lens. John White at www.aiconversions.com will do the work for about $35 to allow these older lenses to be safely used on any Nikon digital camera. If you own or may someday purchase one of those other cameras, you’ll want to consider having the lens conversion done, even though your D3400 doesn’t require it to use the lens safely.

Today, in addition to its traditional full-frame lenses, Nikon offers lenses with the DX designation, which is intended for use only on DX-format cameras, like your D3400. While the lens mounting system is the same, DX lenses have a coverage area that fills only the smaller frame, allowing the design of more compact, less-expensive lenses especially for non-full-frame cameras. The AF-S DX Nikkor 35mm f/1.8G, a fixed focal length (non-zoom) lens with a fast f/1.8 maximum aperture, is an example of such a lens.

Ingredients of Nikon’s Alphanumeric Soup

Nikon has always been fond of appending cryptic letters and descriptors onto the names of its lenses. Here’s an alphabetical list of lens terms you’re likely to encounter, either as part of the lens name or in reference to the lens’s capabilities. Not all of these are used as parts of a lens’s name, but you may come across some of these terms in discussions of particular Nikon optics:

- AF, AF-D, AF-I, AF-S, AF-P. In all cases, AF stands for autofocus when appended to the name of a Nikon lens. An extra letter is added to provide additional information. A plain old AF lens is an autofocus lens that uses a slot-drive motor in the camera body to provide autofocus functions (and so cannot be used in AF mode on the entry-level models noted earlier). The D means that it’s a D-type lens (described later in this listing); the I indicates that focus is through a motor inside the lens; and the S means that a super-special (Silent Wave) motor in the lens provides focusing. (Don’t confuse a Nikon AF-S lens with the AF-S [Single-Servo Autofocus mode].) The P represents the quiet stepping motor that’s especially useful when recording videos with sound. Nikon is currently upgrading its older AF lenses with AF-S or AF-P versions, but it’s not safe to assume that all newer Nikkors are AF-S/AF-P, or even offer autofocus. For example, the PC-E Nikkor 24mm f/3.5D ED perspective control lens must be focused manually, and Nikon offers a surprising collection of other manual focus lenses to meet specialized needs.

- AI, AI-S. All Nikkor lenses produced after 1977 have either automatic aperture indexing (AI) or automatic indexing-shutter (AI-S) features that eliminate the previous requirement to manually align the aperture ring on the camera when mounting a lens. Within a few years, all Nikkors had this automatic aperture indexing feature (except for G-type lenses, which have no aperture ring at all), including Nikon’s budget-priced Series E lenses, so the designation was dropped at the time the first autofocus (AF) lenses were introduced.

- D. Appended to the maximum f/stop of the lens (as in f/2.8D), a D-Series lens is able to send focus distance data to the camera, which uses the information for flash exposure calculation and 3D Color Matrix II metering.

- DC. The DC stands for defocus control, which allows managing the out-of-focus parts of an image to produce better-looking portraits and close-ups.

- DX. The DX lenses are designed for use with digital cameras using the APS-C-sized sensor having the 1.5X crop factor. The image circle they produce isn’t large enough to fill up a full 35mm frame at all focal lengths, but they can be used on Nikon’s full-frame models using the automatic/manual DX crop mode.

- E. The E designation was used for Nikon’s budget-priced E-Series optics, five prime and three zoom manual focus lenses built using aluminum or plastic parts rather than the preferred brass parts of that era, so they were considered less rugged. All are effectively AI-S lenses. They do have good image quality, which makes them a bargain for those who treat their lenses gently and don’t need the latest autofocus features. They were available in 28mm f/2.8, 35mm f/2.5, 50mm f/1.8, 100mm f/2.8, and 135mm f/2.8 focal lengths, plus 36-72mm f/3.5, 75-150mm f/3.5, and 70-210mm f/4 zooms. (All these would be considered fairly “fast” today.)

However, today the E designation is applied to lenses to represent those that stop down the lens to the “taking” aperture electronically. (During framing, focusing, exposure metering, and other pre-photo steps, the lens always remains at its maximum aperture unless you stop it down using a Preview—depth-of-field preview—button.) Non-E lenses use a lever in the camera body that mates with a lever in the lens mount. Lenses with an E in their names, such as the 16-80mm f/2.8-4E ED VR optic, use an electronic mechanism instead. You should be aware that many older film and digital camera bodies (those produced prior to the D3 and D3000, introduced in 2007, plus the Nikon D90) are unable to adjust the aperture of this type of E lens, and must be used wide-open.

- ED (or LD/UD). The ED (extra-low dispersion) designation indicates that some lens elements are made of a special hard and scratch-resistant glass that minimizes the divergence of the different colors of light as they pass through, thus reducing chromatic aberration (color “fringing”) and other image defects. A gold band around the front of the lens indicates an optic with ED elements. You sometimes find LD (low dispersion) or UD (ultra-low dispersion) designations.

- FX. When Nikon introduced the Nikon D3 as its first full-frame camera, it coined the term “FX,” representing the nominal 24mm × 36mm sensor format as a counterpart to “DX,” which was used for its 16mm × 24mm APS-C-sized sensors. Although FX hasn’t been officially applied to any Nikon lenses so far, expect to see the designation used more often to differentiate between lenses that are compatible with any Nikon digital SLR (FX) and those that operate only on DX-format cameras, or in DX mode when used on an FX camera like the D700, D800, D3, D3s, D3x, and D4.

- G. G-type lenses have no aperture ring, and you can use them at other than the maximum aperture only with electronic cameras like the D3400 that set the aperture automatically. Fortunately, this includes all Nikon digital dSLRs.

- IF. Nikon’s internal focusing lenses change focus by shifting only small internal lens groups with no change required in the lens’s physical length, unlike conventional double helicoid focusing systems that move all lens groups toward the front or rear during focusing. IF lenses are more compact and lighter in weight, provide better balance, focus more closely, and can be focused more quickly.

- IX. These lenses were produced for Nikon’s long-discontinued Pronea 6i and S APS film cameras. While the Pronea could use many standard Nikon lenses, IX lenses cannot be mounted on any Nikon digital SLR.

- Micro. Nikon uses the term micro to designate its close-up lenses. Most other vendors use macro instead.

- N (Nano Crystal Coat). Nano Crystal lens coating virtually eliminates internal lens element reflections across a wide range of wavelengths, and is particularly effective in reducing ghost and flare peculiar to ultra-wide-angle lenses. Nano Crystal Coat employs multiple layers of Nikon’s extra-low refractive index coating, which features ultra-fine crystallized particles of nano size (one nanometer equals one millionth of a mm).

- NAI. This is not an official Nikon term, but it is widely used to indicate that a manual focus lens is Not-AI, which means that it was manufactured before 1977, and therefore cannot be used safely on modern digital Nikon SLRs (other than the retro Df model) without modification.

- NOCT (Nocturnal). Used primarily to refer to the prized Nikkor AI-S Noct 58mm f/1.2, a “fast” (wide aperture) prime lens, with aspherical elements, capable of taking photographs in very low light.

- PC (Perspective Control). A PC lens is capable of shifting the lens from side to side (and up/down) to provide a more realistic perspective when photographing architecture and other subjects that otherwise require tilting the camera so that the sensor plane is not parallel to the subject. Older Nikkor PC lenses offered shifting only, but more modern models, such as the PC-E Nikkor 24mm f/3.5D ED lens introduced early in 2008 allow both shifting and tilting.

- PF (Phase Fresnel). When appended to the name of a lens, the PF designation means the lens contains a special lens element specifically included to reduce chromatic aberration (a color fringing phenomenon discussed in the wide-angle lens section of this chapter). The PF element replaces the multiple lens elements required for traditional optical designs, producing a lens that is lighter and smaller.

- UV. This term is applied to special (and expensive) lenses designed to pass ultraviolet light.

- UW. Lenses with this designation are designed for underwater photography with Nikonos camera bodies, and cannot be used with Nikon digital SLRs.

- VR. Nikon has an expanding line of vibration reduction (VR) lenses, including several very affordable models and the AF-S DX Nikkor 16-85mm f/3.5-5.6G ED VR lens, which shifts lens elements internally to counteract camera shake. The VR feature allows using a shutter speed up to four stops slower than would be possible without vibration reduction, according to Nikon. Nikon adds a II or III label to indicate updated VR versions.

What Lenses Can Do for You

No one can afford to buy even a percentage of the lenses available. The sanest approach to expanding your lens collection is to consider what each of your options can do for you and then choose the type of lens and specific model that will really boost your creative opportunities. So, in the sections that follow, I’m going to provide a general guide to the sort of capabilities you can gain for your D3400 by adding a lens to your repertoire.

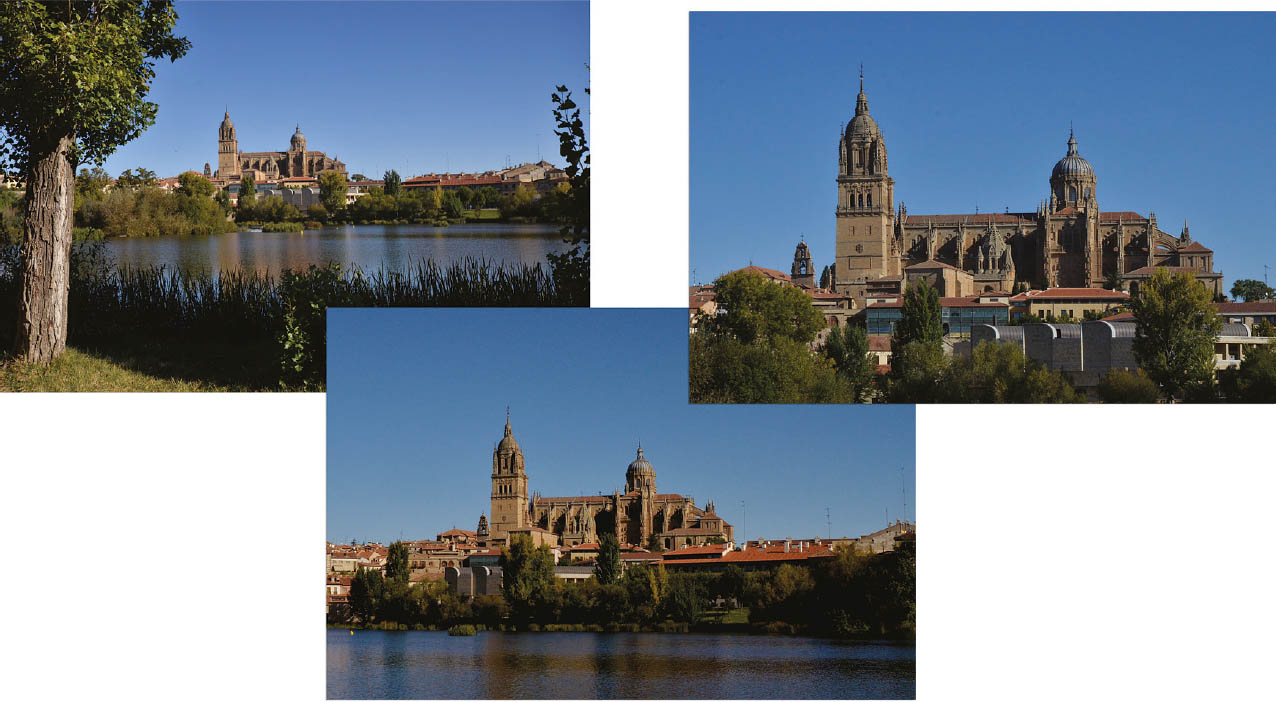

- Wider perspective. Your 18-140mm f/3.5-5.6, 18-55mm f/3.5-5.6, or 16-85mm f/4-5.6 lens has served you well for moderate wide-angle shots. Now you find your back is up against a wall and you can’t take a step backward to take in more subject matter. Perhaps you’re standing on the rim of the Grand Canyon, and you want to take in as much of the breathtaking view as you can. You might find yourself just behind the baseline at a high school basketball game and want an interesting shot with a little perspective distortion tossed in the mix. Figure 10.5, upper left, shows the perspective you get from an ultra-wide-angle 16mm focal length.

- Bring objects closer. A long lens brings distant subjects closer to you, offers better control over depth-of-field, and avoids the perspective distortion that wide-angle lenses provide. They compress the apparent distance between objects in your frame. Don’t forget that the Nikon D3400’s crop factor narrows the field of view of all these lenses, so your 70-300mm lens looks more like a 105mm-450mm zoom through the viewfinder. Figure 10.5 lower center and upper right were taken from the same position, but with an 85mm and 500mm focal length, respectively.

- Bring your camera closer. Macro lenses allow you to focus to within an inch or two of your subject. Nikon’s best close-up lenses are all their 10 fixed focal length optics in the 40mm to 200mm range, but you’ll find good macro zooms available from Sigma and others. They don’t tend to focus quite as close, but they provide a bit of flexibility when you want to vary your subject distance (say, to avoid spooking a skittish creature).

Figure 10.5 An ultra-wide-angle lens 16mm optic, an 85mm telephoto, and a 500mm super-telephoto provided these views of the old and new cathedrals in Salamanca, Spain.

- Look sharp. Many lenses are prized for their sharpness and overall image quality. While your run-of-the-mill lens is likely to be plenty sharp for most applications, the very best optics are even better over their entire field of view (which means no fuzzy corners), are sharper at a wider range of focal lengths (in the case of zooms), and have better correction for various types of distortion. Of course, these lenses cost a great deal more (Nikon alone has a dozen that cost $1,000 or more each).

- More speed. Your Nikon 70-300mm f/4.5-5.6 telephoto zoom lens might have the perfect focal length and sharpness for sports photography, but the maximum aperture won’t cut it for night baseball or football games, or, even, any sports shooting in daylight if the weather is cloudy or you need to use some ungodly fast shutter speed, such as 1/4000th second. You might be happier to gain a full f/stop with a (non-zooming) AF-S Nikkor 300mm f/4D IF-ED for about $1,500. Or, maybe you just need the speed and can benefit from an f/1.8 or f/1.4 prime lens. They’re all available in Nikon mounts (there’s even an 85mm f/1.4 and 50mm f/1.4 for the real speed demons). With any of these lenses you can continue photographing under the dimmest of lighting conditions without the need for a tripod or flash.

- Special features. Accessory lenses give you special features, such as tilt/shift capabilities to correct for perspective distortion in architectural shots. You’ll also find macro lenses, including the AF-S Micro-Nikkor 60mm f/2.8G ED. Fisheye lenses like the AF DX Fisheye-Nikkor 10.5mm f/2.8G ED (which, I should note, does not autofocus on the D3400), and all other VR (vibration reduction) lenses also count as special-feature optics.

Zoom or Prime?

Zoom lenses have changed the way serious photographers take pictures. One of the reasons that I still own 12 (almost worthless) SLR film bodies dating back to the pre-zoom days is that in ancient times it was common to mount a different fixed focal length prime lens on various cameras and take pictures with two or three cameras around your neck (or tucked in a camera case) so you’d be ready to take a long shot or an intimate close-up or wide-angle view on a moment’s notice, without the need to switch lenses. It made sense (at the time) to have a half-dozen or so bodies (two to use, one in the shop, one in transit, and a couple backups). Zoom lenses of the time had a limited zoom range, were heavy, and not very sharp (especially when you tried to wield one of those monsters hand-held). That’s all changed today. Smaller, longer, sharper zoom lenses, many with VR features, are available.

When selecting between zoom and prime lenses, there are several considerations to ponder. Here’s a checklist of the most important factors. I already mentioned image quality and maximum aperture earlier, but those aspects take on additional meaning when comparing zooms and primes.

- Logistics. As prime lenses offer just a single focal length, you’ll need more of them to encompass the full range offered by a single zoom. More lenses mean additional slots in your camera bag, and extra weight to carry. Just within Nikon’s line alone you can choose from a good selection of general-purpose (if you can count AF lenses that won’t autofocus with the D3400 as “general purpose”) prime lenses in 28mm, 35mm, 50mm, 85mm, 100mm, 135mm, and 200mm focal lengths, all of which are overlapped by the 18-200mm zoom I mentioned earlier. Even so, you might be willing to carry an extra prime lens or two in order to gain the speed or image quality that lens offers.

- Image quality. Prime lenses usually produce better image quality at their focal length than even the most sophisticated zoom lenses at the same magnification. Zoom lenses, with their shifting elements and f/stops that can vary from zoom position to zoom position, are in general more complex to design than fixed focal length lenses. That’s not to say that the very best prime lenses can’t be complicated as well. However, the exotic designs, aspheric elements, and low-dispersion glass can be applied to improving the quality of the lens, rather than wasting a lot of it on compensating for problems caused by the zoom process itself.

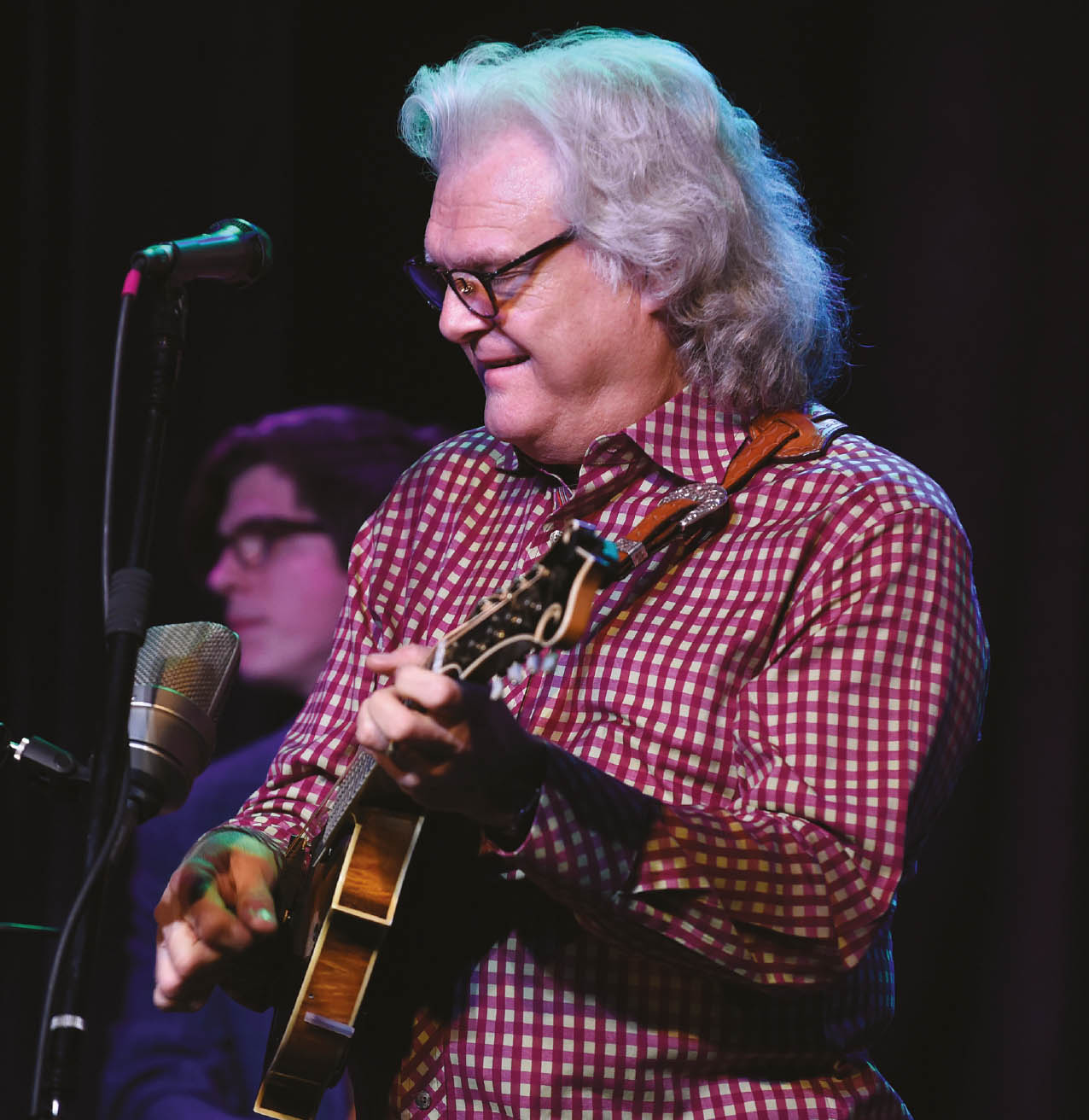

- Maximum aperture. Because of the same design constraints, zoom lenses usually have smaller maximum apertures than prime lenses, and the most affordable zooms have a lens opening that grows effectively smaller as you zoom in. The difference in lens speed verges on the ridiculous at some focal lengths. For example, the 18-55mm basic zoom gives you a 55mm f/5.6 lens when zoomed all the way out, while prime lenses in that focal length commonly have f/1.8 or faster maximum apertures. Indeed, the fastest f/2, f/1.8, f/1.4, and f/1.2 lenses are all manual focus primes (at least on the D3400, because they are AF models), and if you require speed, a fixed focal length lens is what you should rely on. Figure 10.6 shows an image taken with a Nikon 85mm f/1.4 lens.

- Speed. Using prime lenses takes time and slows you down. It takes a few seconds to remove your current lens and mount a new one, and the more often you need to do that, the more time is wasted. If you choose not to swap lenses, when using a fixed focal length lens, you’ll still have to move closer or farther away from your subject to get the field of view you want. A zoom lens allows you to change magnifications and focal lengths with the twist of a ring and generally saves a great deal of time.

Figure 10.6 An 85mm f/1.4 lens was perfect for this hand-held photo at a concert featuring bluegrass legend Ricky Skaggs.

Categories of Lenses

Lenses can be categorized by their intended purpose—general photography, macro photography, and so forth—or by their focal length. The range of available focal lengths is usually divided into three main groups: wide angle, normal, and telephoto. Prime lenses fall neatly into one of these classifications. Zooms can overlap designations, with a significant number falling into the catch-all, wide-to-telephoto zoom range. This section provides more information about focal length ranges, and how they are used.

When the 1.5X crop factor (mentioned at the beginning of this chapter) is figured in, any lens with an equivalent focal length of 10mm to 16mm is said to be an ultra-wide-angle lens; from about 16mm to 30mm is said to be a wide-angle lens. Normal lenses have a focal length roughly equivalent to the diagonal of the film or sensor, in millimeters, and so fall into the range of about 30mm to 40mm on a D3400. Short telephoto lenses start at about 40mm to 70mm, with anything from 70mm to 250mm qualifying as a conventional telephoto. For the Nikon D3400, anything from about 300mm to 400mm or longer can be considered a super-telephoto.

Using Wide-Angle and Wide-Zoom Lenses

To use wide-angle prime lenses and wide zooms, you need to understand how they affect your photography. Here’s a quick summary of the things you need to know.

- More depth-of-field. Practically speaking, wide-angle lenses offer more depth-of-field at a particular subject distance and aperture. (But, see the sidebar below for an important note.) You’ll find that helpful when you want to maximize sharpness of a large zone, but not very useful when you’d rather isolate your subject using selective focus (telephoto lenses are better for that).

- Stepping back. Wide-angle lenses have the effect of making it seem that you are standing farther from your subject than you really are. They’re helpful when you don’t want to back up, or can’t because there are impediments in your way.

- Wider field of view. While making your subject seem farther away, as implied above, a wide-angle lens also provides a larger field of view, including more of the subject in your photos.

- More foreground. As background objects retreat, more of the foreground is brought into view by a wide-angle lens. That gives you extra emphasis on the area that’s closest to the camera. Photograph your home with a normal lens/normal zoom setting, and the front yard probably looks fairly conventional in your photo (that’s why they’re called “normal” lenses). Switch to a wider lens and you’ll discover that your lawn now makes up much more of the photo. So, wide-angle lenses are great when you want to emphasize that lake in the foreground, but problematic when your intended subject is located farther in the distance.

- Super-sized subjects. The tendency of a wide-angle lens to emphasize objects in the foreground, while de-emphasizing objects in the background can lead to a kind of size distortion that may be more objectionable for some types of subjects than others. Shoot a bed of flowers up close with a wide angle, and you might like the distorted effect of the larger blossoms nearer the lens. Take a photo of a family member with the same lens from the same distance, and you’re likely to get some complaints about that gigantic nose in the foreground.

- Perspective distortion. When you tilt the camera so the plane of the sensor is no longer perpendicular to the vertical plane of your subject, some parts of the subject are now closer to the sensor than they were before, while other parts are farther away. So, buildings, flagpoles, or NBA players appear to be falling backward, as you can see in Figure 10.7. While this kind of apparent distortion (it’s not caused by a defect in the lens) can happen with any lens, it’s most apparent when a wide angle is used.

Figure 10.7 Tilting the camera back produces this “falling back” look in architectural photos.

The DOF advantage of wide-angle lenses is diminished when you enlarge your picture; believe it or not, a wide-angle image enlarged and cropped to provide the same subject size as a telephoto shot would have the same depth-of-field. Try it: take a wide-angle photo of a friend from a fair distance, and then zoom in to duplicate the picture in a telephoto image. Then, enlarge the wide shot so your friend is the same size in both. The wide photo will have the same depth-of-field (and will have much less detail, too).

- Steady cam. You’ll find that you can hand-hold a wide-angle lens at slower shutter speeds, without need for vibration reduction, than you can with a telephoto lens. The reduced magnification of the wide-lens or wide-zoom setting doesn’t emphasize camera shake like a telephoto lens does.

- Interesting angles. Many of the factors already listed combine to produce more interesting angles when shooting with wide-angle lenses. Raising or lowering a telephoto lens a few feet probably will have little effect on the appearance of the distant subjects you’re shooting. The same change in elevation can produce a dramatic effect for the much-closer subjects typically captured with a wide-angle lens or wide-zoom setting.

Avoiding Potential Wide-Angle Problems

Wide-angle lenses have a few quirks that you’ll want to keep in mind when shooting so you can avoid falling into some common traps. Here’s a checklist of tips for avoiding common problems:

- Symptom: converging lines. Unless you want to use wildly diverging lines as a creative effect, it’s a good idea to keep horizontal and vertical lines in landscapes, architecture, and other subjects carefully aligned with the sides, top, and bottom of the frame. That will help you avoid undesired perspective distortion. Sometimes it helps to shoot from a slightly elevated position so you don’t have to tilt the camera up or down.

- Symptom: color fringes around objects. Lenses are often plagued with fringes of color around backlit objects, produced by chromatic aberration, which is produced when all the colors of light don’t focus in the same plane or same lateral position (that is, the colors are offset to one side). This phenomenon is more common in wide-angle lenses and in photos of subjects with contrasty edges. Some kinds of chromatic aberration can be reduced by stopping down the lens, while all sorts can be reduced by using lenses with low diffraction index glass (or ED elements, in Nikon nomenclature) and by incorporating elements that cancel the chromatic aberration of other glass in the lens. The PF (phase fresnel) element included in some recent Nikon lenses is specifically designed to counter chromatic aberration.

- Symptom: lines that bow outward. Some wide-angle lenses cause straight lines to bow outward, with the strongest effect at the edges. In fisheye (or curvilinear) lenses, this defect is a feature, as you can see in Figure 10.8. When distortion is not desired, you’ll need to use a lens that has corrected barrel distortion. Manufacturers like Nikon do their best to minimize or eliminate it (producing a rectilinear lens), often using aspherical lens elements (which are not cross-sections of a sphere). You can also minimize barrel distortion simply by framing your photo with some extra space all around, so the edges where the defect is most obvious can be cropped out of the picture. Some image editors, including Photoshop and Photoshop Elements and Nikon Capture NX, have a lens distortion correction feature.

- Symptom: dark corners and shadows in flash photos. The Nikon D3400’s built-in electronic flash is designed to provide even coverage for lenses as wide as 17mm. If you use a wider lens, you can expect darkening, or vignetting, in the corners of the frame. At wider focal lengths, the lens hood of some lenses (my 18-70mm lens is a prime offender) can cast a semi-circular shadow in the lower portion of the frame when using the built-in flash. Sometimes removing the lens hood or zooming in a bit can eliminate the shadow. Mounting an external flash unit, such as the mighty Nikon SB-910 can solve both problems, as this high-end flash unit (it costs almost as much as the D3400 camera) has zoomable coverage up to as wide as the field of view of a 14mm lens when used with the included adapter. Its higher vantage point eliminates the problem of lens hood shadow and helps with red-eye, too.

Figure 10.8 Many wide-angle lenses cause lines to bow outward toward the edges of the image; with a fish-eye lens, this tendency is considered an interesting feature.

Using Telephoto and Tele-Zoom Lenses

Telephoto lenses also can have a dramatic effect on your photography, and Nikon is especially strong in the long-lens arena, with lots of choices in many focal lengths and zoom ranges. You should be able to find an affordable telephoto or tele-zoom to enhance your photography in several different ways. Here are the most important things you need to know. In the next section, I’ll concentrate on telephoto considerations that can be problematic—and how to avoid those problems.

- Selective focus. Long lenses have reduced depth-of-field within the frame, allowing you to use selective focus to isolate your subject. You can open the lens up wide to create shallow depth-of-field, or close it down a bit to allow more to be in focus. The flip side of the coin is that when you want to make a range of objects sharp, you’ll need to use a smaller f/stop to get the depth-of-field you need. Like fire, the depth-of-field of a telephoto lens can be friend or foe. Figure 10.9 shows a photo of a lizard shot with a 200mm lens and a wider f/2.8 f/stop to de-emphasize the distracting background.

Figure 10.9 A wide f/stop helped isolate the lizard while allowing the background to go out of focus.

- Getting closer. Telephoto lenses bring you closer to wildlife, sports action, and candid subjects. No one wants to get a reputation as a surreptitious or “sneaky” photographer (except for paparazzi), but when applied to candids in an open and honest way, a long lens can help you capture memorable moments while retaining enough distance to stay out of the way of events as they transpire.

- Reduced foreground/increased compression. Telephoto lenses have the opposite effect of wide angles: they reduce the importance of things in the foreground by squeezing everything together. This compression even makes distant objects appear to be closer to subjects in the foreground and middle ranges. You can use this effect as a creative tool to squeeze subjects together.

- Accentuates camera shakiness. Telephoto focal lengths hit you with a double whammy in terms of camera/photographer shake. The lenses themselves are bulkier, more difficult to hold steady, and may even produce a barely perceptible see-saw rocking effect when you support them with one hand halfway down the lens barrel. Telephotos also magnify any camera shake. It’s no wonder that vibration reduction is popular in longer lenses.

- Interesting angles require creativity. Telephoto lenses require more imagination in selecting interesting angles, because the “angle” you do get on your subjects is so narrow. Moving from side to side or a bit higher or lower can make a dramatic difference in a wide-angle shot, but raising or lowering a telephoto lens a few feet probably will have little effect on the appearance of the distant subjects you’re shooting.

Avoiding Telephoto Lens Problems

Many of the “problems” that telephoto lenses pose are really just challenges and are not that difficult to overcome. Here is a list of the seven most common picture maladies and suggested solutions.

- Symptom: flat faces in portraits. Head-and-shoulders portraits of humans tend to be more flattering when a focal length of 50mm to 85mm is used. Longer focal lengths compress the distance between features like noses and ears, making the face look wider and flat. A wide angle might make noses look huge and ears tiny when you fill the frame with a face. So stick with 50mm to 85mm focal lengths, going longer only when you’re forced to shoot from a greater distance, and wider only when shooting three-quarters/full-length portraits, or group shots.

- Symptom: blur due to camera shake. Use a higher shutter speed (boosting ISO if necessary), consider an image-stabilized lens, or mount your camera on a tripod, monopod, or brace it with some other support. Of those three solutions, only the first will reduce blur caused by subject motion; a VR lens or tripod won’t help you freeze a race car in mid-lap.

- Symptom: color fringes. Chromatic aberration is the most pernicious optical problem found in telephoto lenses. There are others, including spherical aberration, astigmatism, coma, curvature of field, and similarly scary-sounding phenomena. The best solution for any of these is to use a better lens that offers the proper degree of correction, or stop down the lens to minimize the problem. But that’s not always possible. Your second-best choice may be to correct the fringing in your favorite RAW conversion tool or image editor. Photoshop’s Lens Correction filter (found in the Filter menu) offers sliders that minimize both red/cyan and blue/yellow fringing.

- Symptom: lines that curve inward. Pincushion distortion is found in many telephoto lenses. You might find after a bit of testing that it is worse at certain focal lengths with your particular zoom lens. Like chromatic aberration, it can be partially corrected using tools like the correction tools built into Photoshop and Photoshop Elements. You can see an exaggerated example in Figure 10.10, especially at the edge; pincushion distortion isn’t always this obvious.

- Symptom: low contrast from haze or fog. When you’re photographing distant objects, a long lens shoots through a lot more atmosphere, which generally is muddied up with extra haze and fog. That dirt or moisture in the atmosphere can reduce contrast and mute colors. Some feel that a skylight or UV filter can help, but this practice is mostly a holdover from the film days. Digital sensors are not sensitive enough to UV light for a UV filter to have much effect. So you should be prepared to boost contrast and color saturation in your Picture Controls menu or image editor if necessary.

- Symptom: low contrast from flare. Lenses are furnished with lens hoods for a good reason: to reduce flare from bright light sources at the periphery of the picture area, or completely outside it. Because telephoto lenses often create images that are lower in contrast in the first place, you’ll want to be especially careful to use a lens hood to prevent further effects on your image (or shade the front of the lens with your hand).

- Symptom: dark flash photos. Edge-to-edge flash coverage isn’t a problem with telephoto lenses as it is with wide angles. The shooting distance is. A long lens might make a subject that’s 50 feet away look as if it’s right next to you, but your camera’s flash isn’t fooled. You’ll need extra power for distant flash shots, and probably more power than your D3400’s built-in flash provides. The Nikon SB-910 and SB-5000 Speedlights, for example, can automatically zoom its coverage to illuminate the area captured by a 200mm telephoto lens, with three light distribution patterns (Standard, Center-weighted, and Even). (Try that with the built-in flash!)

Figure 10.10 Pincushion distortion in telephoto lenses causes lines to bow inward from the edges.

Telephotos and Bokeh

Bokeh describes the aesthetic qualities of the out-of-focus parts of an image and whether out-of-focus points of light—circles of confusion—are rendered as distracting fuzzy discs or smoothly fade into the background. Boke is a Japanese word for “blur,” and the h was added to keep English speakers from rendering it monosyllabically to rhyme with broke. Although bokeh is visible in blurry portions of any image, it’s of particular concern with telephoto lenses, which, thanks to the magic of reduced depth-of-field, produce more obviously out-of-focus areas (see Figure 10.11).

Figure 10.11 Bokeh is less pleasing when the discs are prominent (top), and less obtrusive when they blend into the background (bottom).

Bokeh can vary from lens to lens, or even within a given lens depending on the f/stop in use. Bokeh becomes objectionable when the circles of confusion are evenly illuminated, making them stand out as distinct discs, or, worse, when these circles are darker in the center, producing an ugly “doughnut” effect. A lens defect called spherical aberration may produce out-of-focus discs that are brighter on the edges and darker in the center, because the lens doesn’t focus light passing through the edges of the lens exactly as it does light going through the center. (Mirror or catadioptric lenses also produce this effect.)

Other kinds of spherical aberration generate circles of confusion that are brightest in the center and fade out at the edges, producing a smooth blending effect, as you can see at bottom in Figure 10.11. Ironically, when no spherical aberration is present at all, the discs are a uniform shade, which, while better than the doughnut effect, is not as pleasing as the bright center/dark edge rendition. The shape of the disc also comes into play, with round smooth circles considered the best, and nonagonal or some other polygon (determined by the shape of the lens diaphragm) considered less desirable.

If you plan to use selective focus a lot, you should investigate the bokeh characteristics of a particular lens before you buy. Nikon user groups and forums will usually be full of comments and questions about bokeh, so the research is fairly easy.

Add-ons and Special Features

Once you’ve purchased your telephoto lens, you’ll want to think about some appropriate accessories for it. There are some handy add-ons available that can be valuable. Here are a couple of them to think about.

Lens Hoods

Lens hoods are an important accessory for all lenses, but they’re especially valuable with telephotos. As I mentioned earlier, lens hoods do a good job of preserving image contrast by keeping bright light sources outside the field of view from striking the lens and, potentially, bouncing around inside that long tube to generate flare that, when coupled with atmospheric haze, can rob your image of detail and snap. In addition, lens hoods serve as valuable protection for that large, vulnerable, front lens element. It’s easy to forget that you’ve got that long tube sticking out in front of your camera and accidentally whack the front of your lens into something. It’s cheaper to replace a lens hood than it is to have a lens repaired, so you might find that a good hood is valuable protection for your prized optics.

When choosing a lens hood, it’s important to have the right hood for the lens, usually the one offered for that lens by Nikon or the third-party manufacturer. You want a hood that blocks precisely the right amount of light: neither too much light nor too little. A hood with a front diameter that is too small can show up in your pictures as vignetting. A hood that has a front diameter that’s too large isn’t stopping all the light it should. Generic lens hoods may not do the job.

When your telephoto is a zoom lens, it’s even more important to get the right hood, because you need one that does what it is supposed to at both the wide-angle and telephoto ends of the zoom range. Lens hoods may be cylindrical, rectangular (shaped like the image frame), or petal shaped (that is, cylindrical, but with cut-out areas at the corners that correspond to the actual image area). Lens hoods should be mounted in the correct orientation (a bayonet mount for the hood usually takes care of this).

Telephoto Converters

Teleconverters (often called telephoto extenders outside the Nikon world) multiply the actual focal length of your lens, giving you a longer telephoto for much less than the price of a lens with that actual focal length. These converters fit between the lens and your camera and contain optical elements that magnify the image produced by the lens. Available in 1.4X, 1.7X, and 2.0X configurations from Nikon, a teleconverter transforms, say, a 200mm lens into a 280mm, 340mm, or 400mm optic, respectively. Given the D3400’s crop factor, your 200mm lens now has the same field of view as a 420mm, 510mm, or 600mm lens on a full-frame camera. At around $500 each, converters are quite a bargain, compared with the price of a super-long telephoto lens. (See Figure 10.12.)

The only drawback is that Nikon’s own TC II and TC III teleconverters can be used only with a limited number of Nikkor AF-S lenses. The compatible models include the AF-S FX Nikkor 200-500mm f/5.6E EDVR, AF-S FX Nikkor 300mm f/4E PF ED VR, 200mm f/2G ED-IF AF-S VR Nikkor, 300mm f/2.8G ED-IF AF-S VR Nikkor, 400mm f/2.8D ED-IF AF-S II Nikkor, 80-200mm f/2.8D ED-IF AF-S Nikkor, 70-200mm f/2.8G ED-IF AF-S VR Zoom-Nikkor, 200-400mm f/4G ED-IF AF-S VR Zoom-Nikkor, 300mm f/4D ED-IF AF-S Nikkor, 500mm f/4D ED-IF AF-S II Nikkor, and 600mm f/4D ED-IF AF-S II Nikkor. These tend to be pricey (or ultra-pricey lenses). Teleconverters from Sigma, Kenko, Tamron, and others cost less, and may be compatible with a broader range of lenses. (They work especially well with lenses from the same vendor that produces the teleconverter.)

Figure 10.12 Teleconverters multiply the true focal length of your lenses—but at a cost of some sharpness and aperture speed.

There are other downsides. While extenders retain the closest focusing distance of your original lens, autofocus is maintained only if the lens’s original maximum aperture is f/4 or larger (for the 1.4X extender) or f/2.8 or larger (for the 2X extender). The components reduce the effective aperture of any lens they are used with, by one f/stop with the 1.4X converter, 1.5 f/stops with the 1.7X converter, and two f/stops with the 2X extender. So, your 200mm f/2.8 lens becomes a 280mm f/4 or 400mm f/5.6 lens. Although Nikon converters are precision optical devices, they do cost you a little sharpness, but that improves when you reduce the aperture by a stop or two. Each of the converters is compatible only with a particular set of lenses, so you’ll want to check Nikon’s compatibility chart to see if the component can be used with the lens you want to attach to it.

If your lenses are compatible and you’re shooting under bright lighting conditions, the Nikon extenders make handy accessories. I recommend the 1.4X version because it robs you of very little sharpness and only one f/stop. The 1.7X version also works well, too, but I’ve found the 2X teleconverter—even the new, improved TC III version—to exact too much of a sharpness and speed penalty to be of much use.

Macro Focusing

Some telephotos and telephoto zooms available for the Nikon D3400 have particularly close focusing capabilities, making them macro lenses. Of course, the object is not necessarily to get close (get too close and you’ll find it difficult to light your subject). What you’re really looking for in a macro lens is to magnify the apparent size of the subject in the final image. Camera-to-subject distance is most important when you want to back up farther from your subject (say, to avoid spooking skittish insects or small animals). In that case, you’ll want a macro lens with a longer focal length to allow that distance while retaining the desired magnification.

Nikon makes an assortment of lenses that are officially designated as macro lenses. The most popular include:

- AF-S Micro-Nikkor 60mm f/2.8G ED. This type-G lens supposedly replaces the type-D lens listed next, adding an internal Silent Wave autofocus motor that should operate faster, and which is also compatible with cameras lacking a body motor, such as the Nikon D40/D40x and D3400. It also has ED lens elements for improved image quality. However, because it lacks an aperture ring, you can control the f/stop only when the lens is mounted directly on the camera or used with automatic extension tubes. Should you want to reverse a macro lens using a special adapter (the Nikon BR2-A ring) to improve image quality or mount it on a bellows, you’re better off with a lens having an aperture ring.

- AF Micro-Nikkor 60mm f/2.8D. This non-AF-S lens won’t autofocus on the Nikon D3400, but, then, you might be manually focusing most of the time when shooting close-ups, and may appreciate the lower cost of an “obsolete” lens.

- AF-S Micro-Nikkor 40mm f/2.8 DX. The latest macro lens in the lineup, this one is an inexpensive (roughly $250) non-full-frame lens produced especially for DX-format cameras like the D3400. It’s sharp and affordable.

- AF-S VR Micro-Nikkor 105mm f/2.8G IF-ED. This G-series lens did replace a similar D-type, non-AF-S version that also lacked VR. I own the older lens, too, and am keeping it because I find VR a rather specialized tool for macro work. Some 99 percent of the time, I shoot close-ups with my D3400 mounted on a tripod or, at the very least, on a monopod, so camera vibration is not much of a concern. Indeed, subject movement is a more serious problem, especially when shooting plant life outdoors on days plagued with even slight breezes. Because my outdoor subjects are likely to move while I am composing my photo, I find both VR and auto-focus not very useful. I end up focusing manually most of the time, too. This lens provides a little extra camera-to-subject distance, so you’ll find it very useful, but consider the older non-G, non-VR version, too, if you’re in the market and don’t mind losing autofocus features.

- AF Micro-Nikkor 200mm f/4D IF-ED. With a price tag of about $1,800, you’d probably want this lens only if you planned a great deal of close-up shooting at greater distances. It focuses down to 1.6 feet, and is manual focus only with the D3400, but provides enough magnification to allow interesting close-ups of subjects that are farther away. A specialized tool for specialized shooting.

- AF-S DX Micro 85mm f/3.5 ED VR. This lens was designed especially for cropped sensor (DX) models like the D3400. It autofocuses on the D3400, it has vibration reduction, and it’s relatively fast at f/3.5, making it an excellent choice for hand-held close-up photography.

- PC Micro-Nikkor 85mm f/2.8D. Priced about the same as the 200mm Micro-Nikkor, this is a manual focus lens (on any camera; it doesn’t offer autofocus features) that has both tilt and shift capabilities, so you can adjust the perspective of the subject as you shoot. The tilt feature lets you “tilt” the plane of focus, providing the illusion of greater depth-of-field, while the shift capabilities make it possible to shoot down on a subject from an angle and still maintain its correct proportions. If you need one of these for perspective control, you already know it; if you’re still wondering how you’d use one, you probably have no need for these specialized capabilities. However, I have recently watched some very creative fashion and wedding photographers use this lens for portraits, applying the tilting features to throw parts of the image wildly out of focus to concentrate interest on faces, and so forth. None of these are likely pursuits of the average Nikon D3400 photographer, but I couldn’t resist mentioning this interesting lens.

You’ll also find macro lenses, macro zooms, and other close-focusing lenses available from Sigma, Tamron, and Tokina. If you want to focus closer with a macro lens, or any other lens, you can add an accessory called an extension tube, like the one shown in Figure 10.13, or a bellows extension. These add-ons move the lens farther from the focal plane, allowing it to focus more closely. Nikon also sells add-on close-up lenses, which look like filters, and allow lenses to focus more closely.

Figure 10.13 Extension tubes enable any lens to focus more closely to the subject.

Vibration Reduction

Nikon has a burgeoning line of lenses with built-in vibration reduction (VR) capabilities. The VR feature uses lens elements that are shifted internally in response to vertical or horizontal motion of the lens, which compensates for any camera shake in those directions. Vibration reduction is particularly effective when used with telephoto lenses, which magnify the effects of camera and photographer motion. However, VR can be useful for lenses of shorter focal lengths, such as Nikon’s 16-80mm, 18-140mm, and 18-55mm VR lenses. Other Nikon VR lenses provide stabilization with zooms that are as wide as 24mm.

Vibration reduction offers two to three shutter speed increments’ worth of shake reduction. (Nikon claims a four-stop gain, which I feel may be optimistic.) This extra margin can be invaluable when you’re shooting under dim lighting conditions or hand-holding a lens for, say, wildlife photography. Perhaps that shot of a foraging deer would require a shutter speed of 1/2000th second at f/5.6 with your AF-S VR Zoom-Nikkor 200-400mm f/4G IF-ED lens. Relax. You can shoot at 1/250th second at f/11 and get a photo that is just as sharp, as long as the deer doesn’t decide to bound off. Or, perhaps you’re shooting indoors and would prefer to shoot at 1/15th second at f/4. Your 16-140mm VR lens can grab the shot for you at its wide-angle position. However, consider these facts:

- VR doesn’t freeze subject motion. Vibration reduction won’t freeze moving subjects in their tracks, because it is effective only at compensating for camera motion. It’s best used in reduced illumination, to steady the up-down swaying of telephoto lenses, and to improve close-up photography. If your subject is in motion, you’ll still need a shutter speed that’s fast enough to stop the action.

- VR adds to shutter lag. The process of adjusting the lens elements, like autofocus, takes time, so vibration reduction may contribute to a slight increase in shutter lag. If you’re shooting sports, that delay may be annoying, but I still use my VR lenses for sports all the time!

- Use when appropriate. You may find that your results are worse when using VR while panning, although newer Nikon VR lenses work fine when the camera is deliberately moved from side to side during exposure. Older lenses can confuse the panning motion with camera wobble and provide too much compensation. You might want to switch off VR when panning or when your camera is mounted on a tripod.

- Do you need VR at all? Remember that an inexpensive monopod might be able to provide the same additional steadiness as a VR lens, at a much lower cost. If you’re out in the field shooting wild animals or flowers and think a tripod isn’t practical, try a monopod first.

VIBRATION REDUCTION: IN THE CAMERA OR IN THE LENS?

The adoption of image stabilization/anti-shake technology into the camera bodies of models from Sony, Olympus, Pentax, and Samsung has revived an old debate about whether VR belongs in the camera or in the lens. Perhaps it’s my Nikon bias showing, but I am quite happy not to have vibration reduction available in the body itself. Here are some reasons:

- Should in-camera VR fail, you have to send the whole camera in for repair, and camera repairs are generally more expensive than lens repairs. I like being able to simply switch to another lens if I have a VR problem.

- VR in the camera doesn’t steady your view in the viewfinder, whereas a VR lens shows you a steadied image as you shoot.

- You’re stuck with the VR system built in to your camera. If an improved system is incorporated into a lens and the improvements are important to you, just trade in your old lens for the new one.

- When building VR in the camera, a compromise system that works with all lenses must be designed. VR in the lens, however, can be custom-tailored to each specific lens’s needs.