Deriving Value From Conversations About Your Brand

Research shows that both online and off-line customer conversations drive purchase decisions — but they require separate marketing strategies.

Nordstrom, the Seattle-based retailer, had a memorable 2017. In early February, Donald Trump, then the newly elected U.S. president, took to Twitter to berate Nordstrom for dropping the Ivanka Trump clothing line, complaining that the company had treated his daughter “so unfairly … terrible!” The tweet set off a powerful reaction in social media. Our research showed the number of weekly mentions of the Nordstrom brand on Twitter and other sites surged by 1,700%, while the tone of those conversations (as measured using natural-language processing, which interprets meaning from adjacent words and context) swung sharply from positive to negative.1 However, in off-line conversations (measured via surveys), the sentiment stayed positive. Amidst these mixed signals, Nordstrom rolled through the 2017 holiday season with a 2.5% sales increase over the prior year.

Divergent conversations about brands are fairly common — and not only for brands that get caught up in controversies.2 Indeed, we studied more than 500 leading consumer brands and found that in most cases there was little correlation between what consumers said about the brands online and what they said off-line, even though both streams of conversation can have big effects on a company’s sales.3

Marketers have long recognized word of mouth as a powerful force affecting how well products perform. Since the advent of Twitter and Facebook, some people now think of social media as “word of mouth on steroids” — the conversation that represents what consumers are saying.4 Yet we found that online and off-line conversations matter for different reasons.

Most studies on social media marketing effectiveness have looked at how brand engagement on specific platforms such as Facebook or Twitter (for example, the likes, shares, retweets, and comments) responds to marketing initiatives as opposed to considering the social ecosystem as a whole. There is little research looking at off-line conversations — those that occur face-to-face at the office watercooler, over the kitchen table, or at a health club — because of the difficulty and cost of measuring them. However, we addressed that challenge by asking selected consumers to recall the product and service categories and brands they talked about the day before, including whether the brand conversations were positive or negative. We examined this survey data for off-line conversations along with social media data so that we could compare the two types of conversations and identify trends in both. We also looked at weekly ad expenditures for specific brands from Numerator, an advertising tracking company, and sales data to create a comprehensive picture of the factors that lead consumers to buy certain brands. (See “About the Research.”)

About the Research

For our research, we developed a proprietary data platform to incorporate online and off-line conversation data on 501 U.S. brands. For the analysis presented here, we collected online data for 2015 and 2016 and off-line data for 2013 through 2016. Online data was collected through key-word searches of Twitter, public Facebook posts, blogs, forums, and consumer review sites. Using natural-language processing, we analyzed whether the conversations were positive or negative. Our continuous survey research program yielded data on brands from an average of 7,000 off-line conversations per week with consumers ages 13 to 69. Respondents were asked to report on whether their conversation about each brand was positive, negative, neutral, or “mixed.” Our initial step was to correlate the online and off-line data streams for all brands. We then did a regression analysis to link the online and off-line conversations to third-party weekly sales data that we acquired for 175 brands, and to weekly ad expenditure data for a subset of 21 of those brands using a method known as market mix modeling.i

We used this approach to study the relationship between online and off-line conversations in 15 industries, including electronics, packaged foods and beverages, telecommunications, finance, and travel. For many of the 500 brands, we were able to obtain third-party sales data, and we paid particular attention to a subset of 21 brands — including Apple, Intel, A&W, Budweiser, Campbell’s, Lay’s, Pepsi, Red Bull, and Revlon — for which we were also able to obtain advertising data.

Our analysis shows that even though online and off-line conversations both drive sales, they operate independently from each other, so they need to be measured and managed separately. Indeed, managers can’t rely solely on social media to represent the entire social ecosystem that affects brand success. We describe our findings in greater detail below and explain the implications for companies’ marketing efforts.

How Customer Conversations Affect Sales

Knowing how people make brand and purchase decisions can be tremendously valuable for companies, particularly those that rely heavily on new-customer acquisition. U.S. consumers spend approximately $51 trillion each year on all manner of goods and services, from soft drinks and mobile phones to airline tickets and auto insurance.5 Given the potential payoff, companies are always looking for ways to influence those choices — and consumer conversations and recommendations represent a major opportunity.

Overall, we found that off-line and online conversations had similar impacts on sales. For the 21 brands we closely studied, we found that 9% of purchase decisions could be traced back to public conversations and engagement that occurred in social media (including Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, blogs, and customer forums). A slightly larger share — 10% of sales — was related to off-line conversations as measured through our continuous surveys. That means some 19% of U.S. consumer purchases could be traced to consumers talking to friends, relatives, colleagues, or others (some of whom they knew only through social media) about brands.

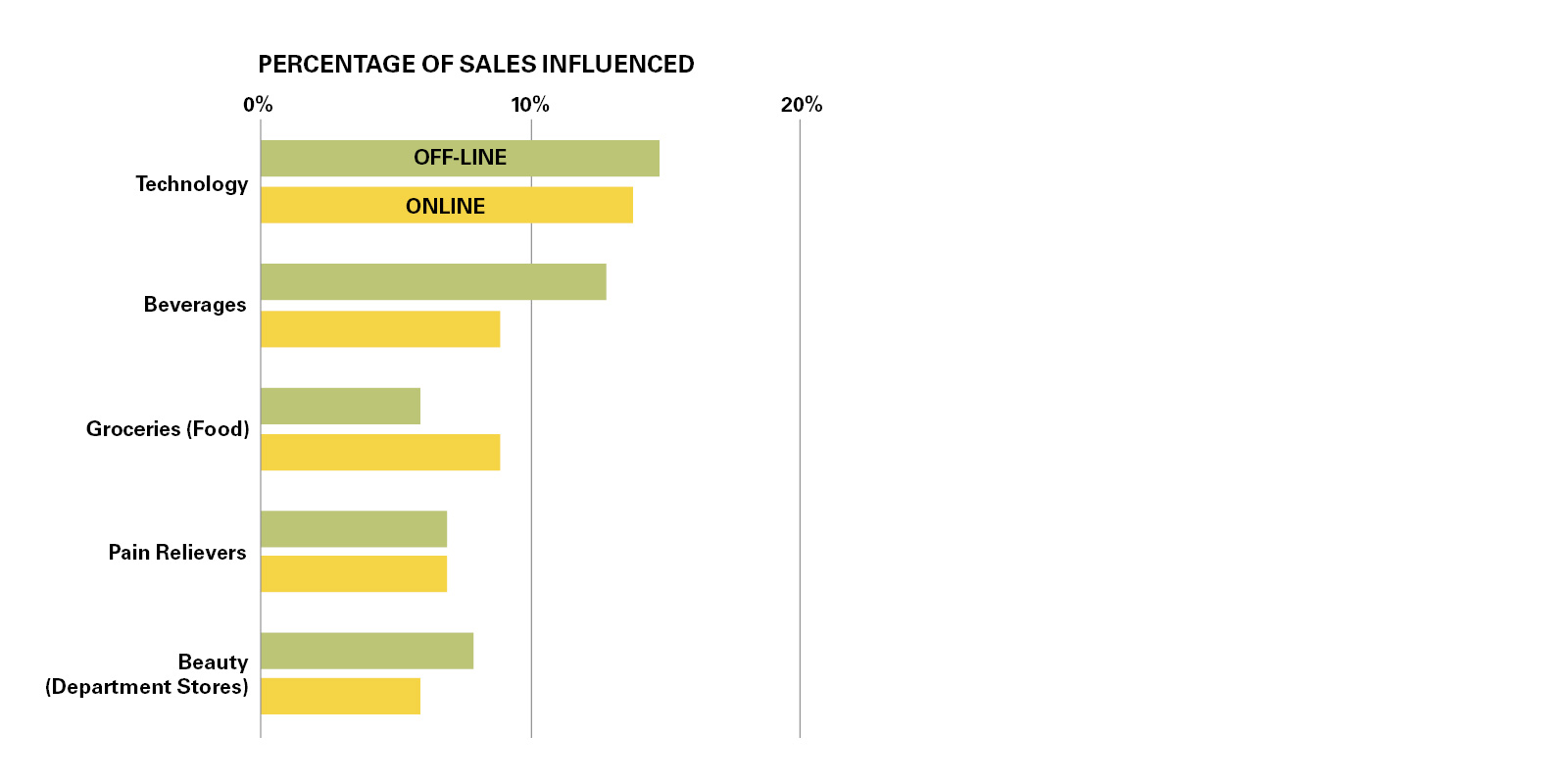

Yet we saw notable differences across product and service categories. (See “What You’re Selling Makes a Difference.”) For example, we had assumed that technology-oriented offerings would skew more toward online conversations than everyday consumer goods, and that products like food (which are often consumed in social situations) might be highly influenced by off-line conversations. However, we found that sales of tech brands like Apple and Intel were driven more by off-line conversations than online, while sales of grocery and food brands such as Campbell’s tended to be driven more by social media than by off-line recommendations from friends.

What You’re Selling Makes a Difference

Although many marketers are focused on consumers’ social media activity, in some categories off-line conversations can be even more influential in driving purchases.

Source: Engagement Labs econometric model for 21 leading brands

The price point of a product or service was often a key factor. Higher-priced goods and services were more apt to be influenced by off-line conversations, perhaps because the stakes were higher and off-line discussions permitted deeper exploration of a brand’s pros and cons than online. Significantly, though, for every product category we studied, the ratio between online and off-line was never more lopsided than 60-40 in either direction, meaning that both types of conversations mattered a lot.

While online conversations are more visible, off-line conversations are more plentiful. Our survey reveals that two-thirds of people talk about brands with at least one friend, relative, or neighbor on any given day, whereas only 7% post, tweet, write, or comment about the products they use. Online conversations tend to be about “social signaling” to one’s network, a term academics use to describe the motivation behind posts about high tech and high fashion.6 Particularly when individuals are trying to appeal to a large group of friends and acquaintances, they craft their online messages to show they are on the leading edge of a trend. Off-line conversations, by contrast, focus on one person and are about various products and services, many of which aren’t “sexy” enough to tweet about or mention on Facebook.

The Metrics That Matter Most

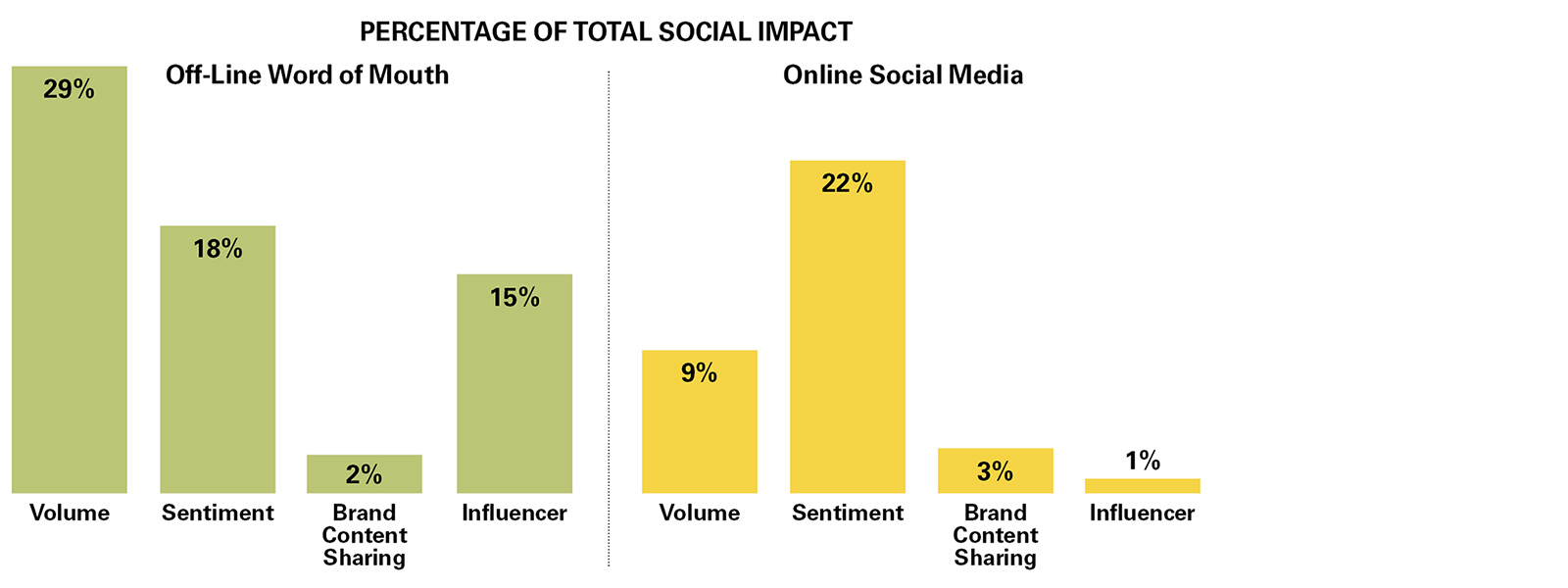

For the brands we studied, the most influential metric was off-line conversation volume as represented by the number of conversations people have about the brand in a week. The more face-to-face conversations and recommendations, the better it is for driving a brand’s sales. For example, each August, Lay’s runs a promotional campaign called Do Us a Flavor in which consumers are asked to vote on a new potato chip flavor. The campaign typically generates a surge in off-line conversations that continues long after the campaign ends. The activity drives brand engagement and purchases at the start of the U.S. professional and college football season, when friends and family watch televised games together and chip consumption rises.

The second most influential metric was “online net sentiment,” which we calculated by subtracting the percentage of negative social media conversations about the brand from the percentage of positive ones. This was followed closely by “off-line net sentiment,” which we calculated similarly, using data from our consumer survey. The importance of the two net sentiment metrics suggests that companies should pay close attention to whether their brands are being talked about positively or negatively, whether online or off-line.

How can companies manage these metrics? Red Bull, the energy drink maker, offers a good example. We found that it effectively drove positive conversations on social media by creating highly entertaining and shareable videos of athletic achievement. But the brand has been less successful at producing positive off-line conversations. Identifying ways to encourage more positive face-to-face conversations may provide new opportunities for Red Bull to drive sales growth. (See “What Has the Biggest Impact on Sales?”)

What Has the Biggest Impact on Sales?

For off-line conversations, the most important metric was the volume, or quantity, of conversations. For online conversations, sentiment mattered more.

Source: Engagement Labs econometric model for 21 leading brands

Online and off-line sentiment often move in opposite directions. In the wake of the February 2018 school shooting in Parkland, Florida, Dick’s Sporting Goods, the large sporting goods retail chain, tightened its gun sale policies and ceased selling assault weapons. The online reaction was extremely negative — people concerned with gun rights denounced the company on social media. But the off-line sentiment was positive. In fact, the company’s revenues rose, and the stock jumped more than 20% upon the announcement of first-quarter results in 2018. This underlined the importance of monitoring both forms of sentiment — online and off-line.7

Yet another metric worth tracking is the extent to which the brand is being talked about off-line by “influencers” — people who regularly give consumer advice. Brands can leverage their market position by encouraging influencers to share what they learn about products with friends and family, expanding the reach of marketing and the speed of adoption.8 Nintendo employed this strategy when it targeted and cultivated “alpha moms” to introduce the original Wii gaming consoles through their real-world social networks.9

One metric that didn’t seem to have much influence, at least on the surface, was “brand content sharing,” which measures the degree to which consumers tell us they are talking about brand advertising (off-line) or have pressed the share button for brand content (online), as they did with Red Bull’s shareable videos. Although we found that the metric ranked low in its immediate impact on sales, its effect was larger: Our model showed that advertising expenditures drove conversations, which, in turn, led to sales. Indeed, conversations among people who know and generally trust one another add persuasive power to the advertising that sparks those conversations.10

Implications for Marketing

Marketers have known for years that customer conversations and recommendations are powerful forms of brand engagement.11 But how can companies leverage those conversations on behalf of their brands?

Broadly speaking, managers should look for ways to drive more positive conversations both online and off-line. In many cases, this will mean going back to marketing fundamentals — rethinking product design, market segmentation, customer service, messaging, and channel selection — with social strategy in mind. To accomplish this efficiently and effectively, we suggest four steps.

1. Determine which conversation drivers have the greatest potential for your business. Large companies with analytics departments may want to build a statistical model as we did, to link conversation data to business results. But companies can use other approaches to figure out which metrics they should focus on. For example, you can learn a lot from your company’s online consumer reviews, as well as those of key competitors. If the reviews are already largely positive (for example, 4.5 out of 5 stars), you can try to stimulate more conversation volume — particularly through off-line recommendations. If your online reviews are less positive than those of competitors, try to improve them. Reach out to customers who gave you so-so ratings, asking them what you could do better, and invite satisfied customers to share their experiences through online comments or tweets. You can also conduct inexpensive online surveys to learn about customers’ off-line recommending behavior (for example, how often they recommend products and what they say). In addition, it might be worthwhile to examine call-center data for themes that correlate with customer satisfaction and dissatisfaction. If the root causes of dissatisfaction are substantial, try to fix them, and encourage those who are satisfied to share their experiences with others. Many travel and restaurant businesses do this by giving friendly reminders to recommend them to others right after a great experience or by providing customers with incentives for referrals. Companies in other industry categories can do the same.

2. Identify the consumer segments that are most likely to enhance sales performance. Once again, there are several ways to do this. Working with a major financial company in the United Kingdom, for example, we mined large databases for insights and found that focusing on the needs of affluent women and targeting them in marketing were the keys to generating the conversations that led to new accounts. Alternatively, some companies have found it useful to conduct small-scale surveys of existing customers to identify who is recommending products or services most often, and why. Having this information can help you deepen relationships with influencers through events, customer care offerings, and other initiatives and reach other prospects through them. Prioritizing customers who simply have large social networks can also be worthwhile; they might be able to recruit other customers to your brand both online and off-line. We have found that a high percentage of consumers who contact a brand via its website, social media, or call centers are influencers.12

3. Refine your messaging and stimulate conversation. Developing shareable marketing content requires creativity as well as statistical analysis. One approach is to monitor social media discussions about your brand to identify themes, and even the language consumers are using when talking about your products and the market in general, and then conduct a small survey to learn how those ideas resonate off-line. Then you can use the most compelling themes and language when developing creative messaging. Another method is to find a way to spark a conversation that is likely to go viral. A 2010 television commercial for Old Spice, the personal care brand, provides a good example. In the ad, the spokesman, a fit ex-NFL player, tells viewers that while every man can’t look like him, they can smell like him. The ad was shared millions of times over YouTube and contributed to an 11% increase in Old Spice sales.

4. Optimize your consumer touch points to support your conversation strategy. Companies often assume that the best avenue for increasing conversation about their offerings is through social media. But as we have shown, conversations spring from a variety of touch points a consumer might have with a brand, so companies can do many other things. For example, in-store product displays can invite consumers to take selfies to share through text messages with friends. Coupons can be designed to generate bonus savings for customers shopping with friends. Email marketing campaigns can encourage people to forward messages to friends or family members. The key is to encourage talking and sharing, and to do it through the various channels you can use to interact with your consumers.

Most brands that attempt to follow consumer conversations choose to concentrate on social media. However, as we have noted, this can point you in the wrong direction. Had Nordstrom executives taken the online conversation about Ivanka Trump’s clothing line as gospel, for example, it might have made decisions that would have hurt sales instead of boosting them. Both off-line and online conversations can have a significant impact on a company’s top line. Understanding the value that each type of conversation may provide — and how — can help businesses develop smarter marketing strategies and make targeted investments that lead to growth.

Brad Fay is the chief commercial officer and Ed Keller is the CEO at Engagement Labs, a data and analytics firm in New Brunswick, New Jersey, where Rick Larkin is vice president for analytics. Koen Pauwels is a professor of marketing at Northeastern University’s D’Amore-McKim School of Business in Boston.

References

1. C. Manning and H. Schütze, “Foundations of Statistical Natural Language Processing” (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999).

2. B. Fay and R. Larkin, “Why Online Word-of-Mouth Measures Cannot Predict Offline Outcomes,” Journal of Advertising Research 57, no. 2 (June 2017): 132-143; B. Fay, “Dick’s Sporting Goods Proves the ‘Noise’ of Social Media Can Give an Incomplete Signal,” June 14, 2018, www.mediapost.com.

3. J. Morrissey, “Brands Closely Monitor Social Media, but Offline Chatter Is Just as Important,” The New York Times, Nov. 27, 2017; and “Return on Word of Mouth,” working paper, Word of Mouth Marketing Association, September 2015.

4. L. Geller, “Why Word of Mouth Works,” May 13, 2013, www.forbes.com; H. Conick, “‘Word of Mouth on Steroids’: Brands Find Success in Peer Endorsements, Study Finds,” Marketing Insights, April 5, 2016; and A. Lane, “Word of Mouth on Steroids — Understanding the Motives of Sharing Content,” Nov. 27, 2017, www.marketingmag.com.au.

5. Trading Economics and U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, total for four quarters ending July 2018, https://tradingeconomics.com.

6. M.J. Lovett, R. Peres, and R. Shachar, “On Brands and Word of Mouth,” Journal of Marketing Research 50, no. 4 (August 2013): 427-444; and A. Barasch and J. Berger, “Broadcasting and Narrowcasting: How Audience Size Affects What People Share,” Journal of Marketing Research 51, no. 3 (June 2014): 286-299.

7. B. Fay, “Dick’s Sporting Goods Proves the ‘Noise’ of Social Media Can Give an Incomplete Signal,” June 14, 2018; and W. Duggan, “Gun Restrictions Don’t Dampen Dick’s Stock,” May 30, 2018, 132-143, https://money.usnews.com.

8. B. Libai, E. Muller, and R. Peres, “Decomposing the Value of Word-of-Mouth Seeding Programs: Acceleration Versus Expansion,” Journal of Marketing Research 50, no. 3 (April 2013): 161-176.

9. D. Chmielewski, “Marketing Moms: Nintendo Reaches Out to a Relatively Untapped Segment of Potential Users in an Effort to Promote Its New Console,” Los Angeles Times, Dec. 25, 2006; and L. Richwine, “Disney’s Powerful Marketing Force: Social Media Moms,” Reuters, June 15, 2015.

10. This “two-step flow” is consistent with work that goes back to the 1950s, when it was devised by researchers at Columbia University and the University of Pennsylvania. See P. Lazarsfeld and E. Katz, “Personal Influence: The Part Played by People in the Flow of Mass Communications” (New York: Free Press, 1955); J. Bughin, J. Doogan, and O. Jørgen Vetvik, “A New Way to Measure Word of Mouth Marketing,” McKinsey Quarterly (April 2010); and M. Trusov, R.E. Bucklin, and K. Pauwels, “Effects of Word-of-Mouth Versus Traditional Marketing: Findings From an Internet Social Networking Site,” Journal of Marketing 73, no. 5 (September 2009): 90-102.

11. J. Bughin, J. Doogan, and O. Jørgen Vetvik, “A New Way to Measure Word of Mouth Marketing,” McKinsey Quarterly (April 2010); and M. Trusov, R.E. Bucklin, and K. Pauwels, “Effects of Word-of-Mouth Versus Traditional Marketing: Findings From an Internet Social Networking Site,” Journal of Marketing 73, no. 5 (September 2009): 90-102.

12. E. Keller and B. Fay, “How to Use Influencers to Drive a Word-of-Mouth Strategy,” WARC Best Practice, April 2016.

i. D. Hanssens, L. Parsons, and R.L. Schultz, “Market Response Models: Econometric and Time Series Analyses” (Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2003): 87-317.

Reprint 60210.

For ordering information, visit our FAQ page. Copyright © Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2018. All rights reserved.