Hour 6

Understanding the Lay of the Land

What You’ll Learn in This Hour:

Summary and Case Study

Summary and Case Study

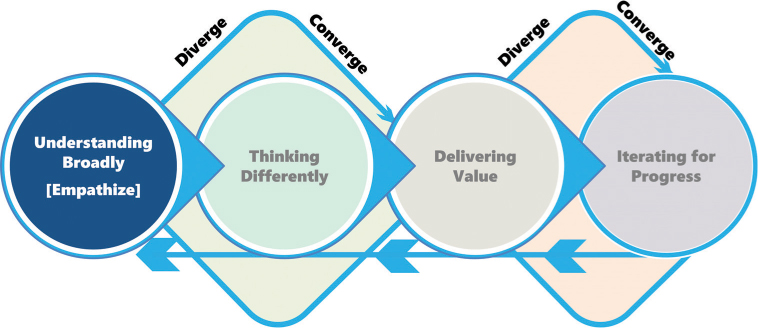

Hour 6 commences Part II, “Understanding Broadly,” where we focus on Phase 2 of our Design Thinking Model for Tech (see Figure 6.1). These next four hours take us on a journey to understand the lay of the land, connect with the right people peppered across this landscape, and learn more about those people as a way to empathize, successfully problem solve, and ultimately create value together. Here in Hour 6 we focus on three areas: listening, understanding, and learning. We do this work of listening, understanding, and learning in the context of a situation or problem. After all, we should understand the lay of the land—the ecosystem, the industry, and the organization and its culture—before we start more deeply connecting and empathizing with the specific people who will make a difference for us. All of this work is embodied in Phase 1 of our Design Thinking Model for Tech, and we pursue it to help us figure out what it’s going to take to successfully solve problems and deliver value. A “What Not to Do” case study focused on the implications of ignoring culture-derived fractals concludes this hour.

FIGURE 6.1

Phase 1 of our Design Thinking Model for Tech.

Listening and Understanding

Listening is a skill. But it’s also a process, and good listening benefits from a bit of preplanning. Before we can be really good listeners, we need to think ahead and intentionally

Know what we need. Think about the information you need and who might be in a position to share that information. More importantly, think deeply about whether we are seeking “a ha” revelations, lessons learned, a history or debrief, feedback on recent events, thoughts on future ideas, or something else.

Know what we need. Think about the information you need and who might be in a position to share that information. More importantly, think deeply about whether we are seeking “a ha” revelations, lessons learned, a history or debrief, feedback on recent events, thoughts on future ideas, or something else. Choose those who know what we need. Consider the balance between purposefully finding and sitting down with an audience versus also being open to having our audience find us and sit us down. Nuggets of wisdom and insight come from everywhere.

Choose those who know what we need. Consider the balance between purposefully finding and sitting down with an audience versus also being open to having our audience find us and sit us down. Nuggets of wisdom and insight come from everywhere. Be present. There is nothing worse than a presumed listener failing to actually listen. All of us know this from experience…it is far too easy to tell when our audience is distracted and therefore not fully present. If we are there to listen, then listen! Put away the phone, shut the lid to our laptop, find a good place without distractions, and be present. Listen and learn and take notes afterward to ensure we do not forget what we just heard, learned, and felt.

Be present. There is nothing worse than a presumed listener failing to actually listen. All of us know this from experience…it is far too easy to tell when our audience is distracted and therefore not fully present. If we are there to listen, then listen! Put away the phone, shut the lid to our laptop, find a good place without distractions, and be present. Listen and learn and take notes afterward to ensure we do not forget what we just heard, learned, and felt. Be self-aware. Listening also means responding in real time to show we are engaged, thinking, and learning. Nodding our head subtly can be useful, as are the occasional simple words of affirmation, but do not overuse these techniques! We all know people who pretend to listen when in fact they are not, and we all know people who listen in such distracting ways that we cannot help but wonder if they are really listening at all. Know ourselves.

Be self-aware. Listening also means responding in real time to show we are engaged, thinking, and learning. Nodding our head subtly can be useful, as are the occasional simple words of affirmation, but do not overuse these techniques! We all know people who pretend to listen when in fact they are not, and we all know people who listen in such distracting ways that we cannot help but wonder if they are really listening at all. Know ourselves.

Note

Need to Listen Better?

Become a better self-aware listener by practicing Active Listening, Silence by Design, and other listening and learning techniques outlined here. In doing so, we can begin to master the art of situational fluency.

Long-time MIT academic Kurt Lewin once said that the best way to understand a situation was to try to change it. Why? Because people will flock to help us understand why change is unnecessary and everything is just fine as it is. Conversely, others will also flock to help explain why a particular change fails to meet their needs or solve their problems. Still others will flock to give their perspectives on how to go about change, what to change, and when to do so.

Through all of the “help” of all of these people, we can grow in our understanding of the situation. But such ad hoc growth does not build the broad understanding we might require or drive the kind of head knowledge and heart empathy necessary for sustainable change. Instead, we should start practicing Active Listening, covered next.

Design Thinking in Action: Active Listening

People are usually quick to say that they are good listeners. But it’s more difficult than we think. It’s a skill that needs to be honed, just like any other skill. To actively listen is to show up and

Be fully engaged, without distractions.

Be fully engaged, without distractions. Continually fight the urge to interrupt, until it is time to do so.

Continually fight the urge to interrupt, until it is time to do so. Rather than interrupting to share our own thoughts, choose instead to reflect what we just heard.

Rather than interrupting to share our own thoughts, choose instead to reflect what we just heard. Reflect our understanding of what we are hearing too, through verbal cues, a smile, a nod of the head, and so on.

Reflect our understanding of what we are hearing too, through verbal cues, a smile, a nod of the head, and so on. Paraphrase when it makes sense to do so, as a way to clarify and condense key themes or learnings.

Paraphrase when it makes sense to do so, as a way to clarify and condense key themes or learnings. Do our part to stay focused on the subject at hand, recognizing that others might take the conversation in other directions.

Do our part to stay focused on the subject at hand, recognizing that others might take the conversation in other directions. Ask questions as needed, remembering to minimize interruptions along the way.

Ask questions as needed, remembering to minimize interruptions along the way.

Remember that Active Listening is about putting away our phones, our laptops, our biases, and everything we think we know. Be present, listen like we are wrong, and learn (see Figure 6.2). There is arguably no better way to learn and empathize than through listening to another’s experiences, their stories, and their unsolicited challenges and pain.

FIGURE 6.2

Active Listening reflects how we show up and stay focused on others. (Pressmaster/Shutterstock)

Design Thinking in Action: Silence by Design

Create and use awkward silence and other healthy discomforts as a way to learn about what’s going on in other people’s minds. Silence by Design is a method for gaining understanding by not filling in the pauses or gaps in a discussion when having a conversation with another person. Instead, let the silence stand…let it sit…and wait. Wait patiently for the other person to finally restart the conversation, all while observing body language and other nonverbal communications.

The idea is simple. When we are quiet, when we choose to listen rather than fill in the blanks with our own ramblings, we give others a gift. We give them the ability to fill in awkward silences with their own insights and with what is really on their mind. Regardless of whether we are having a positive conversation or an argument, Silence by Design can give us a targeted view into what another person is thinking. And what they are feeling. And these insights are like gold.

And during those awkward silences, because we are not struggling to find our own words, we have the opportunity to pay attention more. We have a chance to consider all of the nonverbal reactions and body language surrounding the discussion. Learn from these nonverbal communications—a raise of the eyebrows, folding of the arms, rolling of the eyes, or exasperated shake of the head—to help us figure out where to take the conversation once we have allowed Silence by Design to run its course.

Larry King once observed, “Nothing I say this day will teach me anything. So, if I’m going to learn, I must do it by listening.” Listening takes a number of forms. Initially, we want and need to listen across a wide spectrum to those stakeholders willing to talk. Eventually we will learn to filter the nuggets from the noise, but it’s important to give everyone a fair shot at being heard; don’t exclude people too early from being heard. The most vocal are often the most affected or interested, after all, even if they might be the most difficult or irritating.

And we must listen across a breadth of audiences too, from the top to the bottom, from the bosses to the workers…from the masses in the middle of everything to the people on the “edge” or on the outside who may have valuable learnings and perspectives for us (see Figure 6.3).

FIGURE 6.3

Silence by Design can yield greater insights as we watch and listen across the breath of our stakeholders, potential users, and more.

Note

Shhhhhhh…

When we are quiet—when we choose to listen rather than fill in conversation gaps with our own ramblings—we will eventually find that others fill in those awkward silences with their unique insights and what’s really on their minds.

Design Thinking in Action: Supervillain Monologuing

In the same way that the movies often feature villains who take the time to “reveal their evil plans,” we might need to get the people who have the history with our situation and the landscape as it stands today to monologue about their perspectives…like an evil supervillain! We need to know what’s on their minds, and we need to know how the situation came to evolve to where it is today.

How might we learn what’s on another’s mind? For starters, try inviting a response to open-ended questions that affect their future, such as

“With so many changes taking place around here, what do you think is going to happen next to us?”

“With so many changes taking place around here, what do you think is going to happen next to us?” “What are your plans if this situation plays out like you probably think it will?”

“What are your plans if this situation plays out like you probably think it will?” “What does the future here hold for people like me and you?”

“What does the future here hold for people like me and you?”

Or state something provocative about the current situation or organization as a way to elicit a response:

“How do you think these industry changes will affect us in the long term?”

“How do you think these industry changes will affect us in the long term?” “What do you think about half the leadership team leaving these last six months?

“What do you think about half the leadership team leaving these last six months? “How did Allison not get that promotion to managing director?”

“How did Allison not get that promotion to managing director?” “When was the last time you saw something like that happen!?”

“When was the last time you saw something like that happen!?”

Supervillain Monologuing is useful for engaging with others and understanding what we’ve gotten ourselves into, as we see in Figure 6.4. Through this technique we may discover what the future holds, the ambiguity and other challenges we may face, and the decisions we may need to take. And it’s really easy to do with people who are naturally chatty or prone to oversharing. Find them, engage them, and learn!

FIGURE 6.4

Encouraging others to talk and share their perspectives a la Supervillain Monologuing can lead to even greater insights than Active Listening and Silence by Design.

It’s not difficult to lead unhappy or disgruntled people to talk either. If we are not up for the hard questions, find a willing colleague and tag-team the situation. Together, lead that other person right where they want to go, and sit back and listen and learn. And just remember that no one in these situations is truly an evil supervillain; we are simply using a common engagement technique to learn more.

Design Thinking in Action: Probing for Better Understanding

With a reasonable understanding of a situation or problem, we can finally start drilling or “mining” for details. We do this by asking the kinds of questions that cannot be answered without some thought. In this way, we can achieve the goal of Probing for Understanding, which is to bring clarity to a situation to not only learn more but to avoid mistakes that have been made before.

Probing questions go beyond questions that clarify too. Good probing questions open the back doors as well as the front doors to situations, so we can explore those situations in a 360-degree kind of way. How? By asking open-ended “Why…?” questions and pursuing similar lines of questioning. When we probe and ask deep questions to understand a situation, we are

Looking back into the past, as a way to explain how we got here

Looking back into the past, as a way to explain how we got here Assessing the present day, to understand why things are the way they are

Assessing the present day, to understand why things are the way they are Peering into the future, to think through what might happen when change is introduced

Peering into the future, to think through what might happen when change is introduced

We probe by asking questions that cannot be answered without some thought. The goal is to bring more clarity to a situation, whether current or potential, to avoid mistakes that have been made before and to find a way through the ambiguity ahead of us.

Probing questions must go beyond questions that only clarify, though; probing questions are used to seek and understand the edges of a situation. For this reason, they are open-ended and often preceded with “Why…?”

Importantly, probing questions are not intended to eliminate ambiguity! Complex situations typically reflect a degree of ambiguity, and the investment in time and energy to eliminate all ambiguity is futile. Our goal is to simply cut through the first few “layers” of ambiguity so we can be smarter as we pursue a broader understanding of the lay of the land.

As we strive for greater understanding around why we or others are stuck, we may need to ask deep and probing questions, the kind that really help us unlock the mindset of another person. If we don’t probe to understand why another person thinks a particular way or values a particular thing, or we fail to learn how the current situation came to be, we may never quite understand the nuances that capture that person’s struggles, thinking, and behaviors.

There are several ways to tactfully inquire and truth-seek, but open-ended questions and funnel questions are typically the easiest and most useful. Open-ended questions cannot be answered with a yes or no. They are exploratory in nature, the kind of question that really makes a person avoid automatic responses and actually think about the question. Consider the following examples:

“What was on your mind when you designed this interface?”

“What was on your mind when you designed this interface?” “How did you intend to uncover the requirements?”

“How did you intend to uncover the requirements?” “Why did you think that was a good way to manage a backlog?”

“Why did you think that was a good way to manage a backlog?” “Tell me more about…”

“Tell me more about…”

Funnel questions start with easy questions (ask for names, how things are going, what the person has been doing lately), and once the person being questioned is comfortable, the questions turn more pointed or thoughtful:

“Why haven’t you been more successful in…?”

“Why haven’t you been more successful in…?” “What problems have you overcome during…?”

“What problems have you overcome during…?” “When was the last time you looked at…?”

“When was the last time you looked at…?” “Who told you about…?”

“Who told you about…?”

Despite the way probing (and funnel questions in particular) can feel, the goal of probing is to bring clarity and honesty to a situation. Probing provides understanding, which in turn helps us avoid mistakes and understand more about what’s in front of us.

Probing for Understanding clears a path through the uncertainty ahead of us. To deliver a good Probing for Understanding exercise or line of questioning, keep in mind the following:

Give freedom, space, and time to think to the person being questioned.

Give freedom, space, and time to think to the person being questioned. Do not prematurely answer our own questions or lead our audience down a path of our own making; practice good Silence by Design!

Do not prematurely answer our own questions or lead our audience down a path of our own making; practice good Silence by Design!

Allow questions to sit and sink in and be answered in their own time. Be patient. Chances are we will be rewarded with something we did not already know.

Use provocative or highly emotional questions sparingly.

Use provocative or highly emotional questions sparingly. Avoid bombarding a person with too many tough questions at once.

Avoid bombarding a person with too many tough questions at once. Balance the need to perform basic fact finding with the need to be led down unexpected learning paths (where the real rewards are).

Balance the need to perform basic fact finding with the need to be led down unexpected learning paths (where the real rewards are). Avoid jumping to conclusions; jumping interrupts the flow of information and implies that we think we already have all the answers!

Avoid jumping to conclusions; jumping interrupts the flow of information and implies that we think we already have all the answers! Use our listening skills to identify the right clarifying questions. Clarification will improve both understanding and empathy.

Use our listening skills to identify the right clarifying questions. Clarification will improve both understanding and empathy. Show engagement throughout the communications process.

Show engagement throughout the communications process. Provide thoughtful and authentic feedback to the answers to our questions to show we are listening. Echo especially important aspects of a response or experience or story as a way to reinforce the communicator’s message or invite further detail.

Provide thoughtful and authentic feedback to the answers to our questions to show we are listening. Echo especially important aspects of a response or experience or story as a way to reinforce the communicator’s message or invite further detail. Pay attention to our own body language and facial expressions. Nothing shuts down a hard conversation faster than uncontrolled body language.

Pay attention to our own body language and facial expressions. Nothing shuts down a hard conversation faster than uncontrolled body language.

Probing lets us cut through the slanted viewpoints, the ambiguity, and the little bits of information that people choose to share so that we can learn and see the bigger picture and grow a bit wiser in the process.

Note

Know It All? No Thank You.

Remember that as we Probe for Understanding we need to avoid looking like a know-it-all! Instead, seek to be known as a great listener, to be thought of as a listen-to-it-all.

Assessing the Broader Environment

Once we have listened and probed for understanding, we need to do a bit of research to fill in the gaps. Specifically, we’re looking at gaining a Big Picture Understanding followed by understanding the organization’s culture, workplace climate, and biases.

Design Thinking in Action: Big Picture Understanding

As we briefly covered in Hour 2, gaining a Big Picture Understanding boils down to researching and understanding a number of environmental dimensions that start with a broad pursuit and drive deeper and deeper to better understand

The macroeconomic environment and industry

The macroeconomic environment and industry The company or entity within its industry and environment

The company or entity within its industry and environment The organization or business unit within the company or entity

The organization or business unit within the company or entity

For example, as we see in Figure 6.5, we might first explore the broader industry, economic or regulatory environment, and other macro or big picture matters to learn the answers to questions such as

What is the status and health of the overall industry or landscape (economics, problems, and current trends)?

FIGURE 6.5

By exploring macro and other high-level matters surrounding an organization, we can gain a broad and Big Picture Understanding of that organization.

Which security and compliance mandates are top of mind?

Are there specific industry practices, processes, and quality bars to be considered?

What are the most relevant external pressures and changes (such as competitive pressures, economic changes, or regulatory issues)?

Where does the company or entity rank in its industry and among its competitors?

What differentiates the company from otherwise similar companies? How are they different, and why?

Then we might explore more about the company, its culture and standards, and its specific business and technology problems:

What is the overall vision of the company or entity? Who does it aspire to be, and what is the time frame for that to-be vision?

How well does the company’s current culture reflect who it aspires to be? Where are the gaps?

What is the general state of the company from a financial, customer, partner, employee work/life balance, and employee morale perspective?

How is the company handling external business pressures and changes?

What are the company’s top business or operational pain points and challenges? How are these affected by technology constraints or limitations?

What about its top strategic business or operational strategies or initiatives? Is technology hindering or helping?

With regard to these strategies and initiatives, is the company protecting technology or other sacred cows and the status quo?

Is the company and its leadership team running from something rather than running toward a unifying vision or mission?

How has the company’s business and technology strategy fared lately, and what is changing or could potentially change?

We might then fill in gaps reflecting the company’s specific organization or business unit and its people who are affected by the business and technology situations and problems:

What changes in the business unit’s functional strategies and capabilities are needed?

How well are current functional capabilities delivered? How mature are these delivery capabilities? Where are the key gaps?

For any given business-enabling technology, is there a track record of identifying and rallying around business-specific or technology-specific change drivers?

To what extent is the business unit and its people capable of changing? How has this been demonstrated in previous projects or initiatives?

To what extent does the business unit’s culture enable or prohibit change?

How positively is the business unit perceived internally?

What does “value” mean to the business unit and its people?

Who defines this notion of “value” and how it’s measured?

How stable is the business unit from a leadership and management perspective?

What do the people working in the business unit think about their work, their leaders, their own team, and their all-up organization?

With all of this broad understanding and context in place, we can work through the organization’s situations and problems as we identify the right people and right problems to focus on. Then we need to do some more work and research surrounding culture and the pace of change surrounding the situation and its problems.

Design Thinking in Action: The Culture Snail for Pace of Change

Understanding the big picture and an organization’s broad lay of the land is one thing. Understanding how well a company or business unit can change is another. In any IT project or tech initiative, there’s a natural intersection of technology teams and the business teams who will benefit from the final tech-enabled business solution. At this intersection sits a number of cultural attributes that inform and shape each team, each business unit, the company, and perhaps even the broader industry and macro-economic environment.

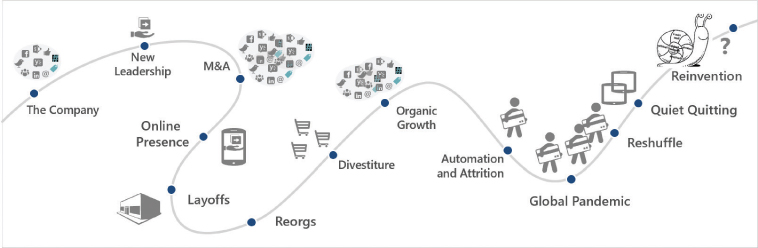

In this multilevel kind of way, we can see culture morph and change a little bit here, a little bit there. This shaping takes time. And the changes come about slowly, a person at a time and a day at a time, moving like a snail making its way on a journey. Like a snail, culture change is organic and alive, slow to move and change, and sometimes amorphous and messy (see Figure 6.6).

FIGURE 6.6

Culture reflects the countless changes reflected by people over time as they join and leave a team and broader organization.

Map this journey! Draw it out with the help of others and consider what you see. An organization’s culture journey tells us about the organization’s ability to change and what that pace of change looks like. It shows us how well the organization can absorb change. Do you see inflection points where change was rapid and adopted well? Do you see other times where change was avoided and stalled the organization? How does this culture journey reflect projects, initiatives, mergers and acquisitions, divestitures, changes in strategy, product launches and product failures, economic downturns, industry changes, and so forth?

Beyond its slow-moving nature, culture is also multidimensional and complex. Consider how our external partners, training organizations, cloud and application vendors, hardware and network providers, and so many others have influenced the status quo culture and ways of working. And turn to the Culture Cube to think more deeply about the dimensions of culture and how they work together to better describe a business unit’s or company’s culture and work climate today.

Design Thinking in Action: The Culture Cube for Understanding

Common sense and experience tell us that we cannot change culture by “changing culture.” Culture initiatives take time and therefore change takes time. Culture is changed or shaped a person at a time and a behavior at a time—and it takes time. Instead, we should seek to first take the following broad-based steps:

Draw on the current culture. The idea here is to meet our people and our teams where they are, just as we do when it comes to developing our people’s capabilities or our organization’s maturity. In this way, we can immediately use and build upon the most valuable existing aspects of our team’s or organization’s culture as we learn to work through existing patterns and biases and start rebuilding momentum for progress.

Intentionally evolve and shape culture. Next, in parallel to drawing on the current culture to make initial progress, we need to shape and redefine over time what it means to be an effective team or a supportive organization. We need to promote specific attitudes, behaviors, and healthy biases, and squash others. And in doing so, we must consider how the current culture will react and evolve across the three dimensions of environment, work climate, and work style.

Our goal here is to gently push the culture to a place where differences are intentionally leveraged for good and take a back seat to achieving a program’s or project’s goals and objectives. We want to take steps to bring teams together, to reward work well done, and to embrace the perspective that the right person for a particular assignment has nothing to do with differences but rather with capabilities, maturity, and attitude.

We must be careful not to inadvertently segregate or separate particular teams or departments from one another. The goal and the right thing to do is to drive inclusion. There are no outsiders on a team, regardless of geographical boundaries or experiences.

And in cases where someone has infringed upon another’s rights or created a less than safe work environment, we must take swift steps to address the problem and set a positive example—not just leaders, but everyone.

Helping one another bring the best that we can bring to work every day is not just a job for leadership; it is everyone’s job and everyone’s responsibility to look out for one another.

How and where do we start? The easiest way to assess our team’s or organization’s culture is to simply look around. What do people do? What seems to be the team’s default and perhaps unwritten Simple Rules and Guiding Principles? How do people act? Which behaviors are tolerated, and which are not? What does the team prioritize and value? What is their track record for getting hard things done? Look and listen!

And pay attention to what other people say about the team—our team—and our organization here and now. These nuggets of solicited and unsolicited feedback and insight reveal an important point-in-time perspective. Such perspectives give us a baseline against which we can later measure our culture’s evolution. For our purposes here as we consider what it means to apply Design Thinking to technology, let us condense culture into a three-dimensional cube reflecting three dimensions and eight perspectives (see Figure 6.7).

FIGURE 6.7

The Culture Cube and its dimensions and perspectives.

As we see from the figure, the culture cube reflects three dimensions: the business unit’s or company’s environment, its work climate, and its work style. Each dimension includes two or more perspectives. To assess an organization’s culture or team’s workplace climate, assess the following:

TIME AND PEOPLE: A Culture Cube exercise requires 3–10 people for 30–120 minutes.

Environment. Consider how people think about their overall workplace.

Harmony, or the ability to work and relate with one another effectively in the workplace.

Harmony, or the ability to work and relate with one another effectively in the workplace. Proficiency, or the desire to continually improve at something that matters and is therefore meaningful (Pink, 2009).

Proficiency, or the desire to continually improve at something that matters and is therefore meaningful (Pink, 2009).

Work Climate. Consider how people work with and relate to one another.

Collective, or the extent to which a team works effectively together, values people and/or the work being done, and shares similar ideas of goals and success.

Collective, or the extent to which a team works effectively together, values people and/or the work being done, and shares similar ideas of goals and success. Individual, or what each team member personally brings to a team in terms of background, experience, biases, values (and respect, initiative, leadership “follow-ship” styles, empathy, conflict management skills, and more).

Individual, or what each team member personally brings to a team in terms of background, experience, biases, values (and respect, initiative, leadership “follow-ship” styles, empathy, conflict management skills, and more). Hierarchy, or the “vertical differences between team members” (Greer, 2018) spanning teams and the overall organization.

Hierarchy, or the “vertical differences between team members” (Greer, 2018) spanning teams and the overall organization.

Work Style. Consider how and when people get things done.

Doing, or how and why work is executed and the extent to which the work is strictly structured and governed (or not).

Doing, or how and why work is executed and the extent to which the work is strictly structured and governed (or not). Thinking, or the planning performed before work is executed.

Thinking, or the planning performed before work is executed. Timing, or when work is executed.

Timing, or when work is executed.

As we know from the Culture Snail, culture moves slowly and in subtle ways, reflecting incremental changes with every new hire brought to a team and every gap left when someone leaves. These individual changes slowly affect and in their small ways change an organization’s culture in terms of the overall environment, the more tactical work climates of each team, and the observed work styles both within and between each team.

Design Thinking in Action: Recognizing and Validating Bias

Another important technique for assessing the broader environment lies in recognizing and validating cross-team and business unit biases. Everyone is biased; we all have our preferences and default ways of thinking and responding. These biases float “up” into our teams, business units, and so on.

For our purposes, biases are akin to really bad mental shortcuts. They’re bad only because they circumvent deep thinking and instead dump our thoughts and automatic responses into the world of assumptions. The key is therefore to see our own biases and recognize biases in others and across our teams. In this way, we can break free from behaviors and patterns that might be keeping us tied to old ways of thinking and executing.

Biases come from what we have experienced and seen in the past, and those biases can be manifested in the present as we unconsciously apply those past experiences to how we work, communicate, collaborate, and make decisions. Because unintentional and unconscious biases hurt people and relationships (and teams and their reputations) just as intentional biases do, it’s important to identify and validate them early.

There are many forms of bias, but when it comes to interacting in healthy ways with other people, several forms of biases easily go overlooked:

Bandwagon bias, or the notion that an idea already adopted by others is the right one for us, too (rather than debating it or setting it aside while we seek additional ideas).

Bandwagon bias, or the notion that an idea already adopted by others is the right one for us, too (rather than debating it or setting it aside while we seek additional ideas). Confirmation bias, which occurs because people want to believe something that confirms what we think we already know.

Confirmation bias, which occurs because people want to believe something that confirms what we think we already know. Framing bias, which occurs when a poor idea is adopted simply because it was presented or “framed” really well.

Framing bias, which occurs when a poor idea is adopted simply because it was presented or “framed” really well. Action bias, or the notion that it is better to do something than nothing even in the absence of information supporting that “something,” which in turn can keep us stuck while we work on the wrong things or head in the wrong direction.

Action bias, or the notion that it is better to do something than nothing even in the absence of information supporting that “something,” which in turn can keep us stuck while we work on the wrong things or head in the wrong direction. Information bias, where people demand more information to make the best decision (keeping us stuck in the meantime).

Information bias, where people demand more information to make the best decision (keeping us stuck in the meantime). Pro-innovation bias, where new ideas are adopted simply because they are new and therefore presumed innovative.

Pro-innovation bias, where new ideas are adopted simply because they are new and therefore presumed innovative. In-group bias, or the practice of dismissing out of hand the ideas that come from groups of people who differ from you in culture, background, experience, education, skin color, height, weight, and infinite other attributes.

In-group bias, or the practice of dismissing out of hand the ideas that come from groups of people who differ from you in culture, background, experience, education, skin color, height, weight, and infinite other attributes.

Biases show up in teams and organizations in the same way they do at an individual level: one person at a time. And biases show up in products and services too. Consider the stories of so many people of color who have to turn over their hands to the “lighter side” to get hands-free sensors to dispense soap and water. Why? Because those sensors were designed for a particular skin tone.

Biases exclude people, shut down innovation, shortcut assumptions, and negatively affect data gathering and feedback sessions. For example, in-group bias will drive teams to favor their own ideas or thinking over other teams’ ideas or thinking. Framing bias will drive a team or an individual to perceive a well-presented idea as perhaps the best idea. Teams, especially those expected to be innovative, will err on the side of action bias rather than risking the perception that they are “thinking (too much) to build.” These biases have zero merit, yet they all too often influence our actions and those of our teams.

So be on the alert for these biases. When you hear phrases such as “that will never get approved by the board” or “we tried that and it failed” or “nobody would want that,” gently call out these statements as perceptions worthy of consideration but reflective of the past. Remind the team that we must learn from our mistakes but remain focused on the future. Find ways of connecting empathy for what we have seen and heard with the desire to hear all perspectives—old and new alike.

We need to keep communications open and flowing. After all, today’s problems are never identical to yesterday’s problems, nor can they always be solved by yesterday’s solutions. And as we will see next, we have a much better chance at solving today’s problems if we can draw on a broader and more diverse cross section of potential ideas.

Design Thinking in Action: Trend Analysis

Our final technique for assessing the broader environment lies in a long-time observation, research, and analysis technique called Trend Analysis. This technique is usually associated with end user and user community trends, but it can be applied more broadly to teams, business units, companies, industries, and other sources.

Trend Analysis requires collecting and analyzing data from the source in question to determine if there is a correlation or relationship present in the data over time. You might assess similarities and differences based on groups of users or other sources and correlate these similarities or differences (deltas) based on the time or day (or week, month, or season), geography, industry, organization, education, language, age, gender, effectiveness, performance, number of errors, choices offered, default decisions made, and so on.

Use Trend Analysis to draw high-level conclusions about a situation’s big picture, an organization’s culture, and a team’s work climate and biases. Take special care to avoid introducing biases in the process. Analyzing trends is error prone and far from foolproof, so for our purposes draw only the broadest of conclusions (and ensure those conclusions are caveated appropriately). The larger the sample size (numbers of users or groups, for example), the better the conclusions and outcomes.

Understanding and Articulating Value

Before we get too far along in our initiatives, projects, and the Design Thinking process, we need to answer a few questions that will one day be critical to our success. For our team, organization, product, solution, and leaders, consider the following:

Do we have a sense of our organization’s and our team’s vision and mission?

Do we have a sense of our organization’s and our team’s vision and mission? What are our broad-based objectives to fulfill our vision and mission?

What are our broad-based objectives to fulfill our vision and mission? What does value look like when those objectives are met?

What does value look like when those objectives are met? Who among a myriad of stakeholders defines this value?

Who among a myriad of stakeholders defines this value? How quickly does value need to be delivered?

How quickly does value need to be delivered? Through what key results will value be measured?

Through what key results will value be measured?

The sooner we understand the attributes of value expected to be delivered through technology, the better chance we have of preserving that focus over time. Later, as we work through connecting and empathizing, ideating, prototyping and testing, and so on, we will naturally return to this notion of value again and again. As we’re solutioning and planning for the delivery of value and other benefits, we’ll identify specific objectives for our work. And we will identify key results useful in measuring the success of that work. For now, though, we simply need a Big Picture Understanding of value as seen through the lens of various stakeholders.

What Not to Do: Ignore the Culture Fractals

Earlier in Hour 3, we briefly looked at Fractal Thinking as a way of considering patterns at scale for thinking differently and deeply. Fractals are all around us, culturally and otherwise. And for a large healthcare company, failing to capitalize on trends seen at scale at a worldwide level and reflected at the industry level and across their competitive landscape cost the organization not only first-mover advantage but a year of stalled work. Had the company recognized the fractal and exercised the courage to push ahead in its vision of instrumenting homes and people for remote care, the company would have been a full year ahead of competitors when COVID shut down much of the world in March of 2020. The fractal eventually played out in a way that fundamentally changed the culture of the health-care industry globally along with many of its key players. This particular fractal echoed downward into companies, public entities, joint partnerships, business units, and teams.

Summary

Throughout Hour 6 we covered techniques and exercises to help us listen better and understand more deeply, including Active Listening, Silence by Design, Supervillain Monologuing, and Probing for Understanding. Next, we outlined techniques and exercises useful in assessing a company’s or business unit’s culture, biases, and other big picture insights. Then we introduced the importance of gaining early visibility into what value looks like, who defines it, and when it needs to be delivered, all of which will be critical in future hours as we ideate, problem solve, prototype, iterate, and start solutioning. A “What Not to Do” real-world example surrounding the implications of ignoring culture fractals concluded this hour.

Workshop

Case Study

Consider the following case study and questions. You can find the answers to the questions related to this case study in Appendix A, “Case Study Quiz Answers.”

Situation

BigBank’s dozen projects and initiatives under the umbrella of the OneBank global business transformation have been taking a toll on the organization’s limited support staff. Satish and the Executive Committee are curious to hear about any techniques that might help each initiative’s leadership team more quickly learn and understand how its respective parts of the business “got to where they are today.” And Satish is personally interested in any technique that can help drive some of the business stakeholders to talk more freely about their own thoughts and perspectives.

Quiz

1. Beyond good active listening skills, what are three “listening and understanding” techniques that might help Satish encourage the organization’s business stakeholders to talk more freely and openly?

2. How might the Culture Snail for Pace of Change help explain how various parts of the business got to where they are today?

3. Which Design Thinking technique helps us view our team’s culture in terms of dimensions and perspectives?

4. When it comes to researching and arriving at a Big Picture Understanding of a company or organization, what are the environmental dimensions that start broad but help us narrow down and understand the organization more deeply?