Hour 12

Exercises for Increasing Creativity

What You’ll Learn in This Hour:

Summary and Case Study

Summary and Case Study

In this hour, we continue to build on Hours 10 and 11 and outline techniques and exercises for thinking differently, in this case to build on or increase creativity. From the basics around Visual and Divergent Thinking, we then turn to unique methods for pushing ourselves to ideate in fresh new ways. Exercises such as Running the Swamp, Fractal Thinking, Golden Ratio Analysis, and Reverse Brainstorming broadly push the notion of guardrails and give us the kinds of “bolt-ons” useful for pushing our thinking beyond the ideation we’ve already completed. We conclude Hour 12 with a “What Not to Do” example focused on real-world missed opportunities when we fail to think through the opportunities in front of us.

Creativity and Thinking

In Hour 11 we discovered techniques and exercises useful for creative thinking, and we organized these methods around the notion of “guardrails” for thinking differently. From Analogy and Metaphor Thinking to Good Enough, Edge Case, Inclusive and Accessible, and Modular Thinking, we outlined new ways of approaching a problem or situation. We then applied creativity to risk management and outlined techniques for extreme thinking.

But what if thinking creatively is simply not adequate? What if we need to not just think creatively but increase our creativity? How might we overlay additional techniques or exercises atop our foundation for thinking to push ourselves in different ways? What are the ideation bolt-ons and recipes that we can use to increase creativity?

In this hour, we take a look at six ways of rethinking what we’ve already thought through to take us in new directions, from Visual and Divergent Thinking to Running the Swamp, Fractal Thinking, Golden Ratio Analysis, and Reverse Brainstorming. Armed with these methods used in conjunction with other methods, we just might find new ways to conquer long-standing problems.

Techniques and Exercises for Creative Thinking

Beyond the guardrails for thinking differently that we’ve already covered, a number of additional exercises can take our brains to new places. Think of these as “bolt-ons” to other ways of thinking. Visual Thinking, for example, is a long-time technique we can add to our tool bag and apply to most any problem or situation regardless of the ways we might have thought about that problem or situation previously.

Design Thinking in Action: Visual Thinking for Understanding

As outlined in Hour 5, the more we can turn our ideas and plans and solutions into pictures and figures—thus making them visible and visual—the faster we will arrive at a shared understanding. Much of this book is organized around techniques and exercises that enable Visual Thinking or the simple process of imaging, showing, looking, and seeing. When we can transform the shapeless and invisible thoughts in our heads into figures and maps and images, we can better think and communicate that thinking and understanding with others. We all know that complex ideas and processes are often best communicated visually, which is why it’s been said that “a picture is worth a thousand words.” A picture can supply exactly what is needed to understand or solve a problem, as we see in Figure 12.1.

FIGURE 12.1

As all of us know first-hand, figures and pictures can transform the complex into the understandable, in this case explaining why someone appears to be quickly driving away from a situation.

When our ideation and thinking processes leave us unable to make more progress or communicate clearly, and when our words fail us, draw a picture. If you are overwhelmed by the complexity of a situation, think about the two or three key parts of that situation—and draw. Pictures help us see relationships and dependencies, and they help us simplify conditions and arrive at a shared understanding faster and more clearly than words.

Beyond pictures, figures, graphs, models, and heatmaps (see the following note), consider active and animated content (videos, for example) to communicate complex processes effectively and with repeatable consistency. For example, viewing one of the hundreds of animated Möbius strips on the Internet (as we discussed in Hour 11) is much better at communicating resource efficiency than these words are.

Note

Heatmapping!

Red/yellow/green heatmaps are wonderful for visualizing data or concepts through the use of color coding (or other identifying marks to accommodate accessibility realities). The variety and gradation of color or other markings help illustrate status or changes, and therefore help draw attention to that status or those changes.

Note

Structured Text

When words are still the best method for communication, consider using Structured Text, outlined later in Hour 15 to communicate crisply and economically.

Design Thinking in Action: Divergent Thinking

As we saw in Hour 10, helping ourselves think more divergently opens the floodgates to new ideas. It’s about generating a range of possibilities rather than discovering the single best or right idea. And with many ideas to further explore, we can create a virtuous cycle where new ideas create more ideas, giving us the volume, depth, and breadth necessary to make progress. Don’t fear mistakes or being “wrong.” Instead, put on our Divergent Hat, enlist the aid of the following Divergent Thinking warm-ups, and bask in new levels of creativity.

Take a walk or go for a run.

Take a walk or go for a run. Get a massage.

Get a massage. Dream about what the future could hold.

Dream about what the future could hold. Draw what is in our head.

Draw what is in our head. Play blocks or LEGO with our kids.

Play blocks or LEGO with our kids. Build something with our hands.

Build something with our hands. Listen to a podcast or music.

Listen to a podcast or music. Take a relaxing bath or shower.

Take a relaxing bath or shower. Meditate and pray in a quiet place.

Meditate and pray in a quiet place.

And remember what Albert Einstein said about the importance of ideas: “The only sure way to avoid making mistakes is to have no new ideas.” Lean on Divergent Thinking tips and techniques to fill up our ideation funnel.

Design Thinking in Action: Running the Swamp

Once we have spent some time thinking deeply through a problem or situation, we might want to turn the tables and instead think rapidly. Without overthinking it, what is our first response to a situation? Without getting buried in potential consequences or root causes, what should be done? Now? It’s this kind of time pressure that can generate the ideas necessary to make progress or survive.

Like earlier techniques and exercises, we can view this exercise through the lens of a group of people. Imagine we need to get ourselves and our community from Point A to Point B, and there is a swamp between the two points. How can we cross the swamp fast enough to avoid sinking into it? How might we cross the swamp in a special kind of way or with a special type of gear? How might we circumvent the swamp? Can we fly over it or run across it like a green basilisk lizard? Time pressure can help us break through logic barriers.

Running the Swamp is a timed Divergent Thinking exercise at its core. The exercise combines various forms of Brainstorming, Analogy and Metaphor Thinking, Visual Thinking, and so on—anything to drive creative ideation. Use this exercise to surface big and bold ideas that would probably not otherwise surface without the time constraint. Hidden in the big and bold are the nuggets of insight that could help us navigate the swamp.

This exercise is best done visually. Obtain a photograph of the community who are at risk of sinking into a swamp and superimpose that photograph over an image of a swamp (see Figure 12.2). For starters, ensure there is plenty of space between the people and the swamp. Throughout this timed exercise, we will watch those people sink into the swamp minute after minute as we fail to come up with ideas and solutions that can help them survive.

FIGURE 12.2

Running the Swamp puts us and our team in a time-crunch situation to ideate rapidly with less thought to common sense or consequences.

Here’s an example of how to Run the Swamp:

TIME AND PEOPLE: A Run the Swamp exercise requires 5–10 people for 5–10-minute blocks of time (though postexercise discussion could take us to 30–45 minutes).

Start the exercise by bringing our group together, sharing the situation and challenge we are facing, and placing the photo of the people affected by the situation atop a larger image of a swamp. Physical and virtual whiteboards are perfect for this exercise.

With the photo mounted well above the image of the swamp, pose the problem or situation again to the team and explain that this is a timed exercise with no bad ideas.

Start the 10-minute timer and commence thinking and brainstorming. How will the community and team traverse the swamp? Capture potential and partial solutions on physical or virtual sticky notes or on the whiteboard.

As each minute elapses, make a show of pushing the photo of the people affected by the situation deeper into the swamp. You might cut off the bottom of the photo if that’s easier. Snip it off! Again, make a show of it to increase the tension in the room or on the call. The community is sinking; the team is failing to rescue the community…

Repeat Step 4 again and again, after each minute elapses.

When the team stalls, introduce different ways of brainstorming. For example, consider running a super-condensed version of a Worst and Best exercise or a Reverse Brainstorming exercise (both covered in Hour 14) as a way to think differently. Rather than fixing the problem, how might this situation turn even worse? (worse than dying in a swamp? Yes.)

Continue updating the visual each minute as the community and team continue to sink deeper. Push the team to consider any kind of solution. Again, capture the proposed solutions on sticky notes or the whiteboard. Show them the impending doom to drive our team to think even more deeply beyond the easy and obvious.

Show the photo of the affected people sinking up to their waist…their chest…their neck… their chin…and feel the pressure increase as the primordial ooze reaches their mouths. There are no crazy ideas. Save them!

Consider how time pressure should have helped the team think of seemingly crazy solutions as failure and death became more and more imminent. Running the Swamp gives people the freedom to share potential solutions that they normally would not be inclined to share, ideas that aren’t constrained by overthinking and citing all of the “that will never work” excuses. We will come up with a mix of solutions, some untenable and others more practical. Still others will be difficult but potentially workable.

Another unexpected outcome of Running the Swamp includes the empathy it builds for the community that must traverse the swamp. Why? Because we’re not watching a project or initiative, or a product or solution, sink into the swamp. Instead, we’re watching the people we’ve been asked to shepherd through a situation get swallowed up. And in this way we find the reason and the courage to think in dramatically new ways.

Note

What Is a Swamp?

Different parts of the world reflect different kinds of danger. Consider renaming Running the Swamp to something more geo-relevant. For example, this exercise is also known as Beating the Train, Crossing the Quicksand, Crossing the Bridge, Wading the Lake, Zombie Crossing, and similar time-sensitive danger-based analogies. Use the one that fits the situation, the geography, the people, or the problem best.

Design Thinking in Action: Fractal Thinking

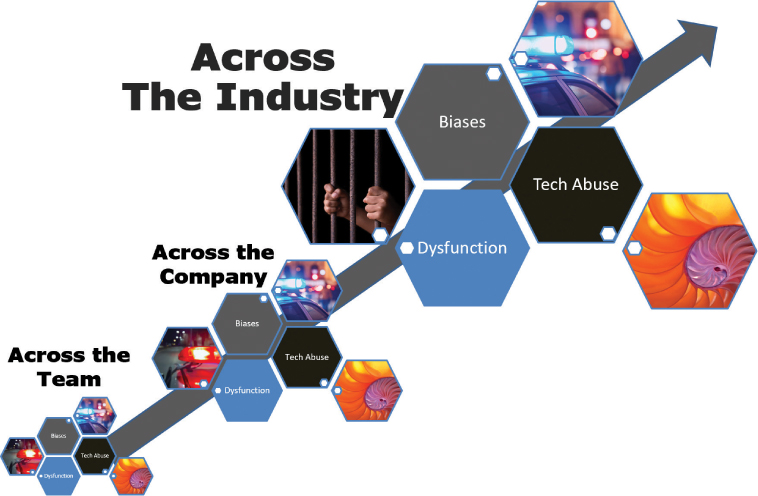

In Hour 9, we covered the Pattern Matching exercise for identifying problems and themes and then briefly touched on a special kind of pattern called a fractal. A fractal is “never-ending, infinitely complex and self-similar like a repetitious feedback loop” (Sheedy, 2021). Fractal Thinking, or “vertical” thinking, gives us another unique lens through which to see problems or situations: the self-similar patterns that exist at smaller or larger scale, such as similar patterns that really just differ in size. A fractal might be smaller than our problem or larger than our problem, but mathematically speaking it’s where X is similar to Y (X ~ Y).

Note

Self-Similar Patterns

Remember that when two geometric objects have exactly the same shape (although not necessarily the same size), then they are said to be similar. When a self-similar pattern exists at different scales, they are said to be fractals of one another.

Fractal Thinking, then, is about recognizing and using the relationship between the small and the large to learn and to think differently. Look for a recursive pattern found over and over again in a particular environment or problem set, and then use this at-scale pattern as a high-level blueprint, design, or guide for influencing change. We might actually hypothesize that what is true at one scale is true at a smaller or a larger scale.

Fractals are seen throughout nature, both here on earth and out across the cosmos. In their similarity there may be something that can be learned and applied, as we see in Figure 12.3.

FIGURE 12.3

Fractal Thinking can help us further ideate on a problem as we move beyond traditional patterns and themes and think vertically.

Fractals help us think through and think differently about a situation in the context of change, where the smallest patterns play out in bigger and bigger circles or in smaller and smaller circles. Consider how patterns seen at home play out in the neighborhood and again across the city. Similarly, consider how patterns in a national government party echo at the state and local levels and are repeated in companies, workplaces, teams, and individual perceptions and actions. Fractals are all around us. Understanding them can help us see with fresh eyes and anticipate what might be coming next.

Fractal Thinking helps us find patterns that help us better understand and fill in the gaps of our own pattern of problems. Need examples? Consider these common fractals seen in nature:

The patterns observed in atoms, solar systems, and galaxies

The patterns observed in atoms, solar systems, and galaxies Tree branches subdividing to smaller self-similar tree branches

Tree branches subdividing to smaller self-similar tree branches Circulatory systems giving way to smaller and smaller yet self-similar blood vessels and capillaries

Circulatory systems giving way to smaller and smaller yet self-similar blood vessels and capillaries River systems being fed by a repeating set of smaller rivers and tributaries and streams

River systems being fed by a repeating set of smaller rivers and tributaries and streams Sponges and seashells, pinecones, pineapples, and even broccoli

Sponges and seashells, pinecones, pineapples, and even broccoli

Fractals allow us to predict and plan for the whole puzzle, even when we see only a piece of the puzzle. Conversely, fractals also help us simplify what might first look to be an incredibly complex landscape, problem, or situation. Apply Fractal Thinking atop other forms of thinking and ideation.

Design Thinking in Action: Golden Ratio Analysis

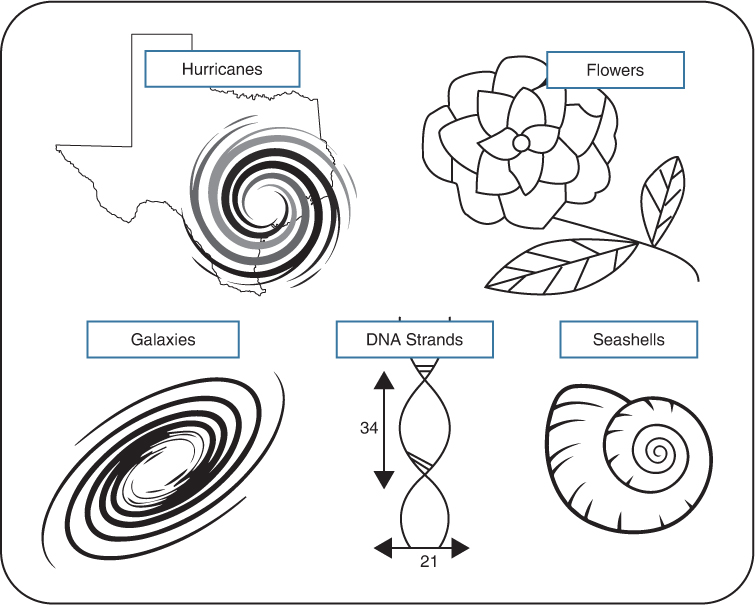

When we look around at the world surrounding us, there are an astonishing number of examples of items that seem to be proportioned just right. From the largest galaxies above to the smallest of plants in the ground, the world is full of examples that just seem to be sized and proportioned in a way that’s pleasing. They make sense; they have a certain natural symmetry. But there’s nothing obvious that explains why they’re pleasing.

In these cases, our observations may be rooted in the fact that the world around us—from galaxies and our solar system to hurricanes and sea shells to strands of DNA and more—reflects a symmetry based on how things naturally grow as captured in the Fibonacci Sequence (which starts 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89 and grows ad infinitum).

When we take a closer look at the numbers in the sequence, we observe a simple pattern. For example, 5+8=13 and 8+13=21. Simply add two adjacent numbers, and we arrive at the next number in the sequence. Cells, flowers, storms, and more grow in very specific ways that often map back to this pattern, explaining, for example, why so many flowers have 5 or 8 or 13 or 21 petals, including why the daisy typically has 34 or 55 petals.

Beyond the pattern, there’s another number at play that sets the stage for a unique and creative thinking technique: the ratio between the two numbers adjacent to one another. The ratio is 1.6 to 1, and we call this the Golden Ratio. This ratio helps explain why fetuses naturally grow the way they do, why faces are pleasing to the eye, why the iPhone just looks right, and why Microsoft’s Azure logo is proportioned just so. Each of these examples reflects the Fibonacci Sequence and more to the point the Golden Ratio. In fact, as we see in Figure 12.4, the world around us has reflected this ratio since the beginning of time. Smart product designers and thinkers realize and use this knowledge. We should too.

FIGURE 12.4

Use the Golden Ratio as a special lens for uncovering unnatural or less-than-optimized relationships within the dimensions of a problem or situation.

Let’s say that we need to move a community from Point A to Point B, and a cursory review of the lay of the land just doesn’t seem right. Something seems out of whack or doesn’t quite look or feel right. We might see issues with the

Dimensions of our journey

Dimensions of our journey Makeup of our staffing model

Makeup of our staffing model Sizing of our sprint work items

Sizing of our sprint work items Structure of our team

Structure of our team Look and feel of our prototype or user interface

Look and feel of our prototype or user interface Makeup of our communications cadences

Makeup of our communications cadences Profiles of our team from a diversity or experience perspective

Profiles of our team from a diversity or experience perspective Specific mix of test cases within our test plans

Specific mix of test cases within our test plans Progression or growth in our risk register

Progression or growth in our risk register

Perhaps we need to consider how the dimensions of the situation or the problem or a potential solution reflect or stray from the Golden Ratio. Perhaps the Golden Ratio can help us validate the natural fit or dimensions of the work in front of us.

In the end, the Fibonacci Sequence does indeed turn out to be the most efficient or practical way for certain organisms or systems of nature to grow and change. Look within our environment, our team, and the processes surrounding us for the natural symmetry reflected in the Golden Ratio. Can we see that ratio at work? Chances are good that if something just feels “off” that the fix might hinge on recognizing and realigning to the Golden Ratio.

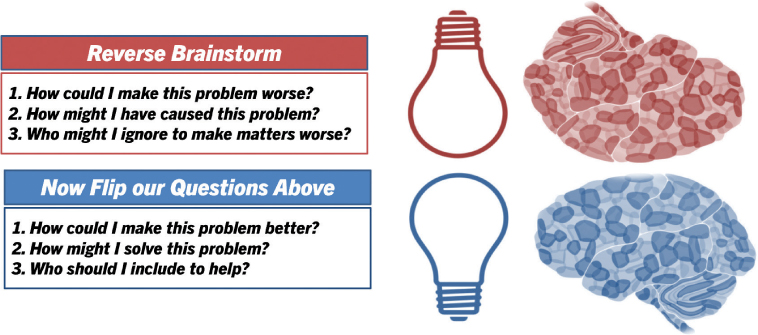

Design Thinking in Action: Reverse Brainstorming

Though we cover this technique in more detail later in Hour 14, Reverse Brainstorming and other thinking-in-reverse techniques and exercises are really smart “bolt-ons” for thinking differently, as we see in Figure 12.5. Before we complete any ideation or thinking exercise, we should conclude with a brainstorming-in-reverse exercise and create a new list of ideas reflecting the problem or situation from a completely different perspective: what would make our problem or situation worse?

FIGURE 12.5

Consider how flipping our logic and running a Reverse Brainstorming session should conclude traditional brainstorming and most any other ideation or thinking exercise.

And such lists are easy to compile. Why? Because most people are naturally wired to think about what could go wrong. It’s one of the few techniques we all use in an almost de facto kind of way. Employed with intention, though, Reverse Brainstorming can give us exactly what we need to think our way out of tough situations: an enormous list of what-not-to-do ideas. With our list in hand of ideas that would make our problem or situation worse, we can then work one by one down the list, flipping each item to transform a what-not-to-do into a possible solution.

For example, if we are faced with a budget shortfall problem, instead of trying to fix this budget problem, we might instead consider what we could do to make our budget problem even worse!

Continue spending more despite already being over budget.

Continue spending more despite already being over budget. Access next year’s budget early.

Access next year’s budget early. Take out a short-term loan.

Take out a short-term loan. Borrow from other departments.

Borrow from other departments. Steal from other departments.

Steal from other departments. Ignore the problem.

Ignore the problem. Keep the problem to ourselves.

Keep the problem to ourselves. Hide the problem using credit cards.

Hide the problem using credit cards. Blame the problem on someone else.

Blame the problem on someone else. Creatively adjust the accounting records to remove the problem.

Creatively adjust the accounting records to remove the problem. Destroy the accounting records.

Destroy the accounting records. Burn down the building and its records.

Burn down the building and its records. Find a new job before the shortfall is realized.

Find a new job before the shortfall is realized.

With this strong list of what-not-to-do actions, we can turn each action around to compile a list of positive actions that we may have missed in traditional brainstorming.

What Not to Do: Concluding Thinking Too Early

A large systems integrator (SI) found itself in dire straits. Its cash cows had dried up, the sales team had failed to replace those dying revenue streams with new sources of income, and a resulting mass exodus of talent left the SI looking like a shell of its former self. The SI’s leadership team employed an outside consultancy to consider and discuss new market prospects, new branding opportunities, and ideas for reinventing the company. Ultimately, an acquisition was orchestrated, the SI was acquired, and a strong legacy of innovation and accomplishment disappeared inside another dying company.

In retrospect, the SI’s leaders realized later that the outside consultancy failed to deeply understand and ideate on its behalf. The consultancy missed the fact that the SI was sitting on a gold mine of assets and IP that in several years would be popularly called “cloud computing.” It missed the fractals echoing across industry, data center technology, and shared-nothing compute platforms. The outside consultancy never pushed beyond what amounted to surface-level brainstorming to really consider the SI’s potential. It failed to fill up an ideation funnel with ideas through divergent thinking techniques. It quit thinking too early, and many paid the price. In the end, the consultancy let down countless shareholders and thousands of people affected by the acquisition, layoffs, and missed market opportunities.

Summary

In Hour 12, we built on the techniques and exercises shared in earlier hours and explored six bolt-on methods for increasing creativity. From Visual and Divergent Thinking to Running the Swamp, Fractal Thinking, Golden Ratio Analysis, and Reverse Brainstorming, we outlined the kinds of thinking and next steps we can use to top off our ideation funnel. Hour 12 concluded with a “What Not to Do” related to missing key opportunities to think divergently and quitting our thinking too early.

Workshop

Case Study

Consider the following case study and questions. You can find the answers to the questions related to this case study in Appendix A, “Case Study Quiz Answers.”

Situation

BigBank’s Chief Digital Officer, Satish, is seeing too many missed opportunities in the way that the various OneBank initiative leaders ideate and execute. He has asked you to host an ideation workshop to explore different ways of improving the team’s creativity and ideation processes.

Quiz

1. Which of the six techniques and exercises is really focused on getting thoughts out of the head and onto paper or a whiteboard as a way to increase shared understanding among a group?

2. Which technique actually consists of many tips and techniques useful for thinking differently?

3. How does a timed exercise such as Running the Swamp drive greater empathy in addition to new ideas?

4. Which technique has us consider patterns playing out at scale below us or beyond us?

5. Which technique asks us to consider how Fibonacci’s Sequence might be affecting the natural fit or dimensions of a particular solution?

6. How might the workshop’s participants collectively view the six creative thinking techniques and exercises, and in particular how classic brainstorming might be naturally augmented?