Chapter 2. Who’s in Control?

Lisa and Ben have been married for a year. Things have been bumpy between them for the past few months, with Ben constantly haranguing Lisa about spending too much time with her friends (“Didn’t you just get brunch last weekend?”) and complaining about how she doesn’t walk their dog until it’s dark outside (“I work until eight, hon,” she protests).

Ben took pains to outfit their apartment with a number of smart devices, including a Nest thermostat and fully connected audio system that he discourages Lisa from using. (“You won’t understand it.”) Because of this, it’s a surprise to Lisa that he’s the one who suggests moving out temporarily to get some space—but she agrees to the separation, privately relieved to have a break from his constant criticism.

The first two days are peaceful. On the third day, Lisa comes home from work, and the apartment feels stifling; the poor dog is panting heavily and nearly out of water. Lisa checks the thermostat and is horrified to see it set to 90 degrees Fahrenheit. She adjusts the Nest, opens the windows, and sleeps uneasily that night. How had she missed that?

The same thing happens the next evening. And the next. Lisa looks up Nest support documentation but doesn’t see anything matching her situation. No one else she knows has one of these things, and she’s worried about hurting the dog. Reluctantly she texts Ben. “Is there some setting I need to know about the Nest? It’s been freaking out.” Ben’s reply is smug: “So now you want me to come back home? I knew you wouldn’t last long.”

Lisa’s confusing and unnerving experience carries the hallmarks of tech abuse used to gaslight victims. Survivors coming from similar situations to Lisa’s have reported their abusers using tactics like changing the temperature, blasting music, or switching lights on and off—all remotely, so their victims can’t be sure about the reason for the chaos and sometimes begin to doubt their own sanity. In this chapter, we’ll look at this phenomenon more closely and identify how safety-minded design could protect people like Lisa from this form of abuse.

A New Frontier in Harm

The modern landscape of internet-connected smart devices offers abusers a multitude of channels to enact control through covert surveillance, stalking, and psychological abuse such as terrorizing and gaslighting. As of 2021, over 40 percent of American homes had at least one smart device, and usage is projected to increase (http://bkaprt.com/dfs37/02-01).

A 2018 New York Times report found that the growing presence of smart devices has been accompanied by an increase in people using them for abuse and control, with workers at domestic violence helplines reporting a significant surge in calls about smart home devices. The article also noted that judges who issue restraining orders may need to begin explicitly mentioning use of these smart devices as falling within the realm of “contact,” because otherwise, the abuse often continues even after a restraining order is in place (http://bkaprt.com/dfs37/02-02).

While internet-connected devices like Nest thermostats are among the newest methods for abusers to control their significant others, other forms of tech enable domineering behavior as well. In 2014, NPR surveyed over seventy shelters to understand how abusers utilize smartphones and GPS in their abuse. Their research revealed that 85 percent of shelters were working with clients whose abusers tracked them with GPS, and 75 percent had clients whose abusers used in-home security cameras or other listening devices to eavesdrop on their conversations remotely.

In an article summarizing the research, Cindy Southworth, who runs the Technology Safety project out of the National Network to End Domestic Violence, explained that “complete and utter domination and control of their victims” is the ultimate goal of abusers:

[I]t’s not enough that they just monitor the victim. They will then taunt or challenge them and say, “Why were you telling your therapist this?” Or “why did you tell your sister that?” Or “why did you go to the mall today when I told you you couldn’t leave the house?” (http://bkaprt.com/dfs37/01-07)

As abuse via smart devices and other tech increases, it’s urgent that technologists understand the ways that various forms of connectivity can be weaponized for abuse. We have the potential to help vulnerable users and prevent an enormous amount of harm by asking ourselves: “Who’s in control?”

Remote Harassment

Researchers have only recently begun to study coercive control via connected devices; unlike more traditional forms of abuse, we do not yet know exactly how widespread the problem is. Our current knowledge comes from firsthand accounts of survivors and those in the domestic violence support space. These accounts show us that the impact of abuse via connected devices is severe:

- A social worker described helping women whose partners locked them inside their own homes using smart locks and also recalled assisting with a woman whose partner would “control the temperatures so it would be hot one minute and freezing the next.” Another survivor told interviewers that when her boyfriend was away from their home, he’d terrorize her by remotely activating smart devices in the middle of the night to blast music, turn on the TV, and flicker the lights (http://bkaprt.com/dfs37/02-03).

- An attorney described an abuser who would remotely unlock a survivor’s car doors, then, during a custody hearing, blame the survivor for endangering their children (http://bkaprt.com/dfs37/02-04).

- In 2016, Chrysler recalled over a million of their vehicles after a pair of hackers demonstrated to Wired magazine that they could remotely take control of an internet-connected 2014 Jeep Cherokee, cutting the transmission while their friend drove it on the highway (the friend was in on this, and it was all done very safely) (http://bkaprt.com/dfs37/02-05). The actions they could have taken, but didn’t, included remotely forcing the car to accelerate and slamming the car’s breaks, as well as suddenly turning the steering wheel at any speed.

The remote nature of abuse via connected devices is insidious: it allows abusers and other bad actors to do harm from afar, often in a manner that gives the survivor little ability to understand how the abuse is happening or take back control. However, this doesn’t mean that connected tech can’t be reformed. As designers, we can use multiple methods to both prevent abuse and help survivors regain power and control.

Add in speed bumps

A very general method for preventing remote harassment is to recognize when it may be occurring and design a speed bump to slow the user down. For example, if a thermostat’s settings are constantly being switched between heating and air-conditioning over a short period of time by a user in the home and a user outside the home, the app might send a message to the user outside the home to ask, “Are you sure? It looks like someone who’s home wants a different temperature.”

While I don’t believe that a feature like this would prevent abuse, it might help to reduce it when used together with other solutions. Putting up this sort of roadblock was shown to decrease bullying in an experiment run by an Illinois teenager, who designed a social media feature that would ask the user if they were sure they wanted to post text that had certain bullying-associated keywords in it. Among users who received the alert asking them to reflect before posting something that might be hurtful, there was a 93 percent reduction in abusive posts (http://bkaprt.com/dfs37/02-06).

An alternative to asking the user to reconsider their behavior is to ask if there’s some kind of problem. Perhaps there’s no control struggle going on, and the device is actually malfunctioning; this would be a way to allow the user to report a legitimate issue. And if the user’s intentions are indeed malicious, this speed bump still offers an opportunity to reconsider their actions before doing harm.

In fact, it’s not only matters of interpersonal safety that can benefit from an experience that’s deliberately slower. Content strategist Margot Bloomstein has written and talked about how intentionally slowing down an online commercial transaction can give customers the time they need to absorb information related to their purchase—resulting in a higher degree of confidence that they’ve bought the right thing (http://bkaprt.com/dfs37/02-07).

These sorts of roadblocks can also completely block the action from being possible at all. For example, a smart car could recognize that the car is currently in use and prevent a user who is far away from it from remotely unlocking the car doors or taking other actions to control the car.

Use these ideas as a jumping-off point to consider within your own products. How might you design a small barrier that can recognize activity that’s indicative of malfunction, user error, or attempt at abuse? Based on the product and its specific potential for harm, you might deliberately slow the user down, ask them to reconsider their action, or even prevent an activity from being possible during certain situations.

Flag activity that indicates abuse

Digital financial products offer a clear example of tech that is rife with control issues between users. According to The National Network to End Domestic Violence (NNEDV), 99 percent of intimate partner violence cases involve financial abuse (http://bkaprt.com/dfs37/02-08). NNEDV also notes that financial abuse is among the most powerful methods abusers have to keep their victim in the relationship and that it’s often a key barrier to a survivor’s ability to stay safe when they leave.

Financial abuse is also widespread outside of intimate partner contexts; financial abuse of the elderly is common, and some parents take advantage of their teenage and young adult children’s inexperience to steal or control their money. This means that the space of digital banking and other finance-related tech has an enormous opportunity to both help prevent abusers from taking control of another person’s finances and to recognize that abuse is possibly happening, which could be easily done using the already-existing tools banks use to identify potential fraud.

For example, credit card companies will commonly flag activities such as a large purchase (like a new refrigerator or speedboat) that seems unusual. This same technology could be used to flag an account that suddenly runs up a large amount of debt, which is a common tactic of abusers; the goal is to ruin the survivor’s credit to make them more financially dependent on the abuser. Another method for ruining a survivor’s credit score is putting bills in their name and then refusing to pay them; and while there are many reasons someone may not be paying a bill, this is an activity that should be flagged as potentially involving an element of financial abuse.

Once potential abuse has been identified, financial institutions are in a key position to give appropriate support. What counts as “appropriate” will vary, but considering banks usually have robust customer service teams, human-to-human support is well within the realm of possibility. Utility companies should also consider the possibility of financial abuse when working with customers who haven’t paid their bills and start with the assumption that the customer may not actually have full control over and access to their finances.

Flagging potentially abusive behavior is possible in other realms as well. Whatever your product, try to identify if there is any behavior that might indicate abuse, and create a design to assist users who may need help. We’ll get more into the nuts and bolts of how to do this in Chapter 5.

Account Ownership

Joint and shared accounts are teeming with struggles over who gets control, and once again, the space of digital personal finance is a prime example. While banks vary on how they handle joint accounts, many are not truly joint accounts at all: they are standard, single-user accounts, modified to allow multiple logins to access them. This means that somewhere in the backend, the account is designed for just one user to have ultimate control. The separate logins aren’t truly separate, and the account isn’t truly joint: it’s an account for one person masquerading as something else.

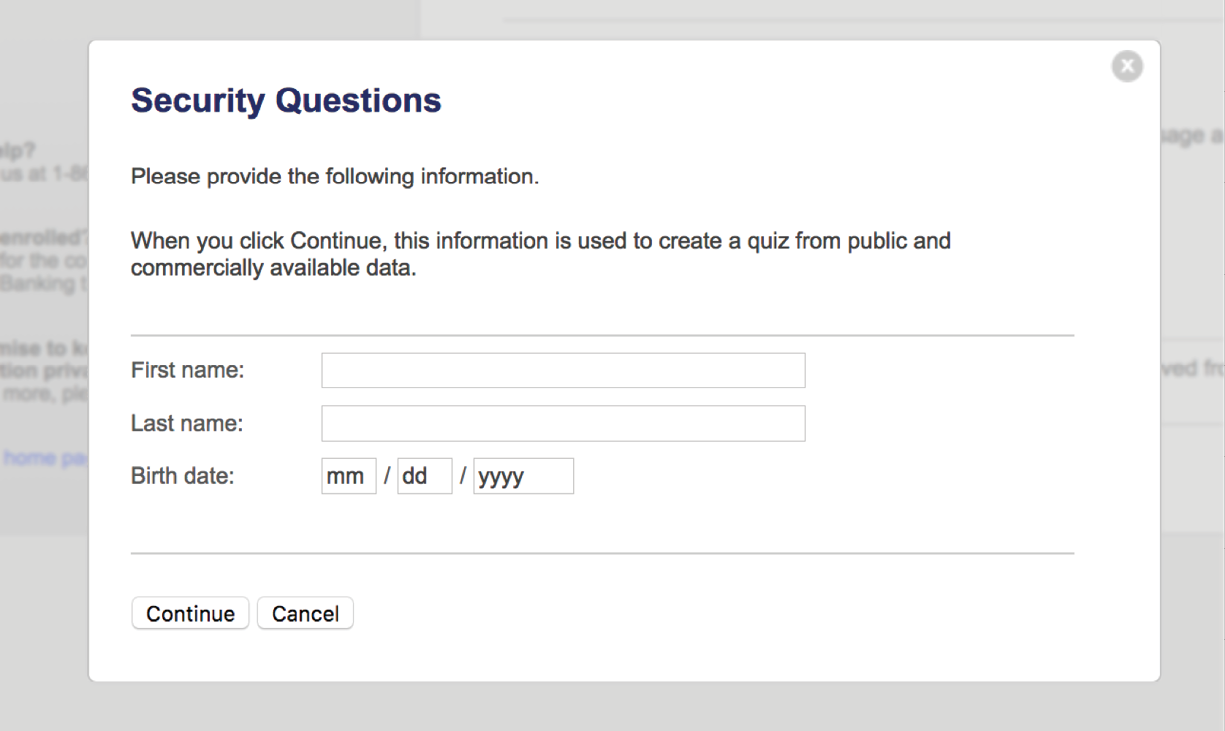

My husband and I set up our joint bank account in person at a local branch, where the banker who helped us set my husband as the primary user—without telling us. This means when I’m prompted to answer the account’s security questions for verification, such as when I log in from a new Wi-Fi network, the questions are based on my husband’s information (Fig 2.1). This gives him a lot more control over the account, as he can deny me access by not providing the answers.

Later on, I opened a new shared account for us on our bank’s website. This time, I was presented with a form that let me set myself as the source of the security quiz questions (Fig 2.2). While I was happy that this account would use my information, it doesn’t solve the problem; it only shifts the control from my husband to me. The only thing to prevent me from restricting his access to the account are my own ethics, not the system’s design.

Single-user accounts masquerading as joint accounts aren’t restricted to banks. This same problem crops up in many apps and services, from cars to grocery stores to phones, where users might assume an account accessed by two people is jointly controlled.

Ensuring shared control and power in online banking tools and other financial tech is key in preventing financial domestic abuse and adequately responding to users who are experiencing it. Most financial institutions are large, slow to change, and operating under numerous laws and regulations, but change is absolutely possible.

Create truly joint accounts

For power to be truly shared, each member on an account must have their own login with their own username and password. Identity verification information must then be tied to the individual.

AT&T does a good job of authentically separating out the user identities of two people with a shared account. Instead of a security quiz drawn from publicly available information, they use two-factor authentication by sending a code via text message. When my AT&T account wanted to verify my identity, it presented both my phone number and my husband’s. This ensures equal access rather than prioritizing one user over another (Fig 2.3).

True joint account ownership also benefits circumstances that have nothing to do with abuse. When interviewing people about their experience with joint bank accounts, I spoke with a man whose wife had passed away several years prior. She had been set as the primary user of their bank account, and it took him over a year to gain full access. Similarly, although my grandmother had given my father full control over all of her finances and marked him as her beneficiary, transferring funds and closing her accounts after she died was still a tedious, time-consuming, and months-long process.

A lack of planning by tech companies for life events that separate people—including breakups, moving out of the parent’s home, and the death of a family member—is a theme that we’ll see again in this book, along with the idea that when we put safety at the heart of our design, we end up creating a better, more inclusive experience for all our users.

Be transparent about who’s in control

My friends Claudia and Mark live in Chicago, and like many people in big cities, both use public transportation to commute to work and only need one car.

Mark had wanted a Tesla Model 3 for ages, and finally, when their old car was on its last legs, Claudia agreed to the purchase. They sat down together with her iPad and paid the $100 deposit to reserve their car.

Several months later, when they received their shiny new car, they realized that the digital account tied to Tesla’s app had been created completely in Claudia’s name. While the title of the car had both their names on it, and legally they both own it, Claudia is the sole digital owner in Tesla’s eyes. This means she has access to the full set of features, such as setting a maximum speed and adding others to the app, while Mark is merely a “Driver,” invited to the account by Claudia. She can remove him from the account with a tap of a finger, which would also remove his ability to access the car itself. There is no way to create a second primary user. Unlike the joint bank account, which sneakily creates a primary and secondary user while pretending all users are the same, the design of the Tesla app accounts forces users into primary and secondary users, without making it clear up front how the division takes place.

When Claudia and Mark reserved their Model 3, they had no idea that their casual decision to make the payment from Claudia’s iPad, which was tied to her Apple Pay account, would be interpreted as authorization to make her the primary user of the car. A better design would have made this clear; a safer design still would allow them to create two primary users and have an authentically joint account. Just like with the joint bank accounts, control is being given to one person in an opaque way.

In an abusive scenario, where Claudia would use this as a form of control over Mark, a design that made it clear how much control Claudia had over the car would give Mark important information about his safety when driving it.

Allow users to “split” accounts

A potential solution to Claudia and Mark’s dilemma is to allow Mark to “detach” his accounts away from Claudia’s and into a new one that has full permissions. In a personal conversation, sociologist and software tester Jorunn Mjøs suggested a feature to “clone” (or copy) an existing account as the basis for a new one as well as the ability to “detach” an individual profile and use it to create a new account. Mjøs’s version of “who’s in control?” is “who gets custody of the algorithm?”

On streaming services such as Spotify and Netflix, the desire for this sort of feature abounds among users who have a profile on a primary user’s account and want to create a new one for themselves while keeping the data from their previous profile. People want (and regularly ask for) this feature for all sorts of reasons, including breakups, moving away from parents or roommates, and being in a place where they can finally afford their own account. Instead, secondary users are left with no options but to start over, while the account holder, or primary user, gets to keep their profile as well as the wealth of data, which is often built up over years and typically includes precise recommendations.

The concept of cloning or detaching a profile and spinning it into a new account is technically complex but by no means impossible and would enable users to turn one account into two, which translates to a new user who already understands the product and is a loyal customer. This is another example of how focusing on designing for safety would make a product better for people in all sorts of situations. For products like the Tesla, which was initially designed for a single primary user, allowing secondary users like Mark to detach his profile and use it to create a primary user profile may be a possible retrofitted solution.

Give customers proper support

It may legitimately not be possible to design a piece of tech in a way that ensures two people get equal control, and your stakeholder may choose to proceed anyway. When this is the case, it is especially important to ensure that there’s a way to talk to a real human at the company. Someone who has the knowledge necessary to help people who are being abused by their product, whether it’s a Tesla user being denied access to the car or someone whose finances are being controlled by an abusive partner.

Claudia and Mark searched for a way to get in touch with someone at Tesla, but “contact us” forms seemed to go nowhere, and they were unable to reach a human being who might be able to make Mark the primary user of their Tesla. In an abusive situation, this would quickly put Mark in danger, as he would have no way to use the car without Claudia knowing. This is why self-serve forms can’t replace human interactions in a way that supports user safety.

For an example of what enhanced support looks like, we can look to two major banks in Australia, the National Australia Bank and the Commonwealth Bank of Australia, who have created hotlines staffed with specially trained employees to assist customers experiencing domestic abuse. The Australian Banking Association set a goal to “minimize the burden” on customers affected by domestic violence by:

- creating guidelines for bank staff that include ensuring the customer’s contact information is kept private from a joint account holder,

- providing copies of documents without a fee, and

- referring customers who want additional help to a local domestic violence organization (http://bkaprt.com/dfs37/02-09).

The hotlines were so popular during the pilot phase that they have become a permanent part of the banks’ overall customer support ecosystem. Banks in other countries, as well as other companies in general, would do well to follow the model of providing customer support specifically to vulnerable user groups. Services like this can help victims of financial abuse quickly regain control over their money and begin to rebuild their financial health, decreasing reliance on an abuser and helping them leave dangerous situations more quickly and safely.

At the end of the day, giving users the ability to get in touch with a human being who can understand complex human situations is essential to both a quality customer experience and to preventing abuse.

Digital vs. Physical Control

When asking “who’s in control” of a piece of tech we’re designing, there are certain scenarios where we should also ask ourselves if digitizing control is the right move in the first place. Sometimes, the fact that we can digitize an analog product doesn’t necessarily mean we should.

Examples abound of connected digital devices presenting frustrating problems that range from the trivial to the serious. A roundup from the Twitter account Internet of Shit (http://bkaprt.com/dfs37/02-10) in late 2020 included gems like:

- internet-connected shoes automatically connecting to their owner’s headphones,

- a couple who changed internet routers and can no longer connect their living room’s smart lightbulbs (“It’s literally been dark in there for months now”), and

- a smart doorbell on a residence inexplicably displaying the booking website for a British hotel, making the doorbell unusable.

And in early 2021, an internet-connected sex toy made headlines when hackers exploited a security vulnerability to lock the devices, demanding ransom before giving back control:

[S]ecurity researchers found that the manufacturer of an Internet of Things chastity cage—a sex toy that users put around their penis to prevent erections that is used in the BDSM community and can be unlocked remotely—had left an API exposed, giving malicious hackers a chance to take control of the devices. That’s exactly what happened. (http://bkaprt.com/dfs37/02-11)

Luckily, the user who spoke to the press about the hack wasn’t wearing the device at the time, but if he had been, the physical implications could have been serious.

In an anecdote my editor told me, a driver found himself unable to drive his Tesla after upgrading his phone, as the car provides few physical fallbacks when the app isn’t functional. In another example, a friend recently told me about a problem with a hybrid car she rented: the battery died, and because the locks were fully digital, she wasn’t able to open the car door. She was lucky to have been in a location where she had cell service and enough power on her phone to stream a video on YouTube that showed her how to access a hidden keyhole to get into the car. This happened to her while alone in a new city on a freezing winter day, which could have meant more trouble.

Digitized control can abruptly turn into “no control” when conditions shift, which is frustrating in best-case scenarios and life-threatening in others. A car can be a literal lifeline to people in domestic violence situations; they are often an instrumental part of survivors’ escape plans. Currently, many cars still operate with a key that opens the doors, but Tesla has migrated most of its controls (including locking and unlocking) over to their app. The company does provide a credit card-like key card meant for valets that can be used as a physical key in a pinch, but this does not solve the problem of a primary user being able to digitally restrict a partner’s access to the car. In cases where an abuser is the “primary” person with full digital control over the vehicle, survivors face an even larger hurdle if they are attempting to leave the relationship.

Smart locks pose the even more dire risk of denying people access to their own homes. Many landlords are switching from traditional keys to smart locks in order to have easier control over who has building access and to reduce headaches when tenants lose physical keys; but not all tenants share their enthusiasm. Apps associated with smart locks can come along with aggressive data collection, including collecting GPS information. With the heightened potential for privacy violations, smart lock systems make it easier for landlords to force evictions, particularly of lower-income tenants who are unlikely to be able to afford an attorney to fight back (http://bkaprt.com/dfs37/02-12).

In Brooklyn, tenants of a rent-controlled building organized against their landlord’s use of internet-connected entry system software that used AI facial recognition, pointing out issues with privacy as well as the overwhelming evidence that AI systems are less accurate when it comes to recognizing the faces of Black people, which could lead to them being locked out of their homes (http://bkaprt.com/dfs37/02-13). This fear is well-founded: a 2019 analysis from the National Institute of Standards and Technology found that top-performing facial recognition systems misidentified Black people at rates five to ten times higher than white people (http://bkaprt.com/dfs37/02-14). (For more on the ways AI and algorithms reproduce racism, see the Resources section.)

Design physical fallbacks

Just because it’s possible to connect something to the internet doesn’t always mean we should. When a client or stakeholder insists on doing so anyway, we designers need to ensure there are physical fallbacks—be it a building’s front door lock, a home’s doorbell, or a chastity cage’s ability to open. Users need to be able to regain control when the high-tech elements inevitably fail—or are tampered with by a hostile party.

Be mindful, too, that common scenarios like owners changing their internet password, purchasing a new router, or updating their phone software won’t brick the entire system.

Who Is the Source of Truth Here?

When devices become digitized and internet connected, issues with transparency around the use of the devices often arise as well. Without the ability to “prove” that an abuser who’s no longer in the home is remotely manipulating the environment, survivors risk not being believed about their abuse—or worse, deemed to be having hallucinations or a psychotic episode. A domestic violence advocate told the New York Times that some of her clients had been put on psychiatric holds to have their mental state evaluated after reporting abuse involving internet of things (IoT) devices (http://bkaprt.com/dfs37/02-02).

Documenting abuse is key to building a case against an abuser, and the way we as technologists can assist in this situation is to put more concrete evidence in survivors’ hands. So how do we build better transparency into these smart devices so that abusers’ activities are no longer hidden from view?

Provide history logs

History logs for connected tech, such as smart home devices and connected cars, offer an avenue for survivors to provide proof of their abuse and combat the type of gaslighting that so many abusers specialize in.

Home Assistant provides an excellent example of how history logs can be kept and viewed by users. The software is designed to be the central control system in a home full of various smart devices, managing them all in one place. Its logs track moment-to-moment user actions as well as regularly scheduled actions, such as turning the lights on at the same time each morning (Fig 2.4).

Should you have the opportunity to introduce history logs to your product, or improve the logging system that may already be in place, consider these essential elements that can help reduce the power of abusers:

- Ensure the history logs include the username of the person who took the action, what the action was, and the date and time it occurred.

- Make history logs available through both the app and the device itself to account for instances when a victim of abuse through that product doesn’t have the app installed.

- Make it clear to users if the logs will not be stored beyond a certain date, as gathering evidence of abuse is important for survivors who engage in the criminal-legal system or have other reasons to want proof of the abuse (such as custody over children). Ideally, history logs would provide data as far back as the device was in use, but a more realistic goal might be to provide history for the previous six months.

- Additionally, you’ll want to think carefully about not just how a user can view the history logs but how they can download or record it so they can use it later as proof of the abuse.

A number of connected devices reveal some data to the user but not to such a granular level as specific user activity. For example, Nest collects an enormous amount of data from its customers to use in its partnerships with utility companies (http://bkaprt.com/dfs37/02-15). However, the company doesn’t share most of this data with its users; perhaps they think no one would want to view a list of all the times someone in their household adjusted the temperature, and at what time, and which user took the action. But if this data were revealed to the user, it would go a long way to help survivors escape gaslighting and make their case to law enforcement. At the bare minimum, users should be able to easily request history logs so that they can increase the chance of their abuse being taken seriously.

Safer Tech Is Transparent

Technology has transformed a plethora of everyday tasks, such as going to the bank, unlocking a door, and starting a car, from in-person analog interactions to high-tech and internet-enabled exchanges. With that change has come a struggle for control over the tech that powers our lives. We must resist privileging the rights of those who would weaponize our tech for abuse. We must instead ask ourselves whose right to control is being enabled—or threatened—with any new piece of tech, and consciously prioritize the rights and safety of our most vulnerable users.

Much of the tech in question is still in a nascent form, meaning we can still course-correct before patterns of harm become the standard. And just because other tech that involves thorny issues of control are more established, such as financial products, doesn’t mean they can’t be rethought. We have the ability to update long-established norms and retrofit them for safety, such as changing the long tradition of people using technology for stalking—the topic of our next chapter.