Sustainable Systems—Order Winners of the Future

More and more companies are extending their commitment to be responsible business practices to their value chains, from subsidiaries to suppliers. They do so not only because of the inherent social and environmental risks and the governance challenges the supply chain poses, but also because of the many rewards supply chain sustainability can deliver.

—George Kell, Executive Director of the United Nations Global Compact

- A study by Johnson Controls found that 96 percent of Generation Y respondents are highly concerned about the environment and expect that employers will take steps toward becoming more sustainable. Over 70 percent of respondents want business to make a real commitment to sustainability.1

- Ford Motor Company hires climate scientists to be part of their planning process and integration of sustainability into decision making. Setting a scenario limit on carbon emissions at 450 parts per million (ppm), Fords’ management makes product development and supply chain decisions while considering future scenario planning and this self-imposed limit.

- The new U.S. workforce increasingly comprises individuals who seek the opportunity to make a contribution to society, and who are choosing jobs that enable them to make this a part of their lives. Case in point, 92 percent of millennials say they want to work for environmentally conscious firms,2 and over 90 percent of millennials say that a company’s success should be measured by more than profit, and over 50 percent say they think businesses will have a greater impact than any other societal segment—including government—on solving the world’s biggest challenges.3

The vignettes we use at the start of each chapter highlight leading companies involved in sustainable supply chain management (SSCM), risks of not being prepared for this business paradigm, and already apparent trends. The examples used in this chapter highlight a number of important facts motivating the need for any organization to cross the chasm and implement the concepts and practices outlined in this book. Why? Because your employees want to be involved in sustainable business practices, leading firms are already integrating sustainability into risk management and even hiring climate scientists so they can be part of teams involved in strategic planning activities, and while we implicitly allow existing systems to be wasteful we now recognize greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and carbon as a measure of this waste knowing that it has a monetary value. Finally, we will need both an internal and external approach to engaging stakeholders for the successful implementation of SSCM.

The overarching goal of this book is to help you better understand SSCM. In doing so, we want you to see your own organization through the lens of sustainability, find intersection opportunities, leverage existing management systems, and evaluate new ways to create value for your organization and supply chain. In this chapter, we take an integrative and forward-looking approach to SSCM with the following objectives.

- Utilize evidence-based management examples of companies successfully developing sustainable supply chains to drive value.

- Provide a structured approach to planning and implementation.

- Review the self-assessment process.

Ford Motor Company

We have asked managers within different industries to relate a story of how their firm changed its strategy using sustainability to guide that change process. While many firms understand the importance of planning for the future we next want to highlight one of them. According to the management at Ford, one of the big enablers of product strategy transformation from a sustainability standpoint was CO2 emissions. If you look at the carbon footprint of Ford, you have the effects created by the vehicles they produce and customers use, manufacturing facilities, suppliers’ facilities, and dealerships. When reviewing the firm’s carbon footprint, and these elements up and down the supply chain, you find that 98 percent of Ford’s footprint comes from their products in use. Thus, the biggest impact Ford can have is to increase fuel economy and, as a result, reduce GHG emissions.

A turning point for Ford was found in the 2007 International Panelon Climate Change (IPCC) report on the impact of climate change, temperature increases, and the tracking of ppm of CO2. Using this report as a catalyst, the leadership at Ford now have climate scientists employed within the company and has publicly acknowledged climate change is real. These scientists have come up with an internal glide path targeting a global 450 ppm threshold. While the targeted number of 450 is debatable as being too high, the fact that CO2 and science are shaping design and strategy decisions is not. The algorithm used helps management to understand their global CO2 targets for any year in the future. You can name the year and management can tell you what their CO2 targets are, and their business unit’s share of allowable CO2. Ford’s decision makers are enamored with this because it provides them with a stable set of guidelines per year that do not change. This way, they know what their fleet and product development should look like one year from now, five years from now, or ten years from now. How did this come about? Starting in 2007 and 2008, Ford’s management teams actually went out and worked with environmental groups such as the Union of Concerned Scientists, Environmental Defense Fund, and others. What they gleaned from these stakeholders is that the most important thing is to get started with an approach to sustainability indicatives based on data and performance metrics such as CO2.

Why is CO2 so important? First, it is an indication of waste as was reviewed in Volume 1, Chapters 2 and 3. Second, consider that China has seven carbon trading platforms. This recognition of emissions as having a price associated with them is substantial given China is the manufacturer to the world and has been the largest emitter of CO2 in absolute terms for the past few years. Simultaneously, California has launched a carbon trading platform where prices are around $15 a ton. Carbon may be the first environmental waste to have a price in most of the major economies of the world, and CO2 certainly will not be the last. Carbon markets are now planned for or operating in Europe, Korea, and Australia where prices are around $23 a ton, and the United States can point to the California exchange as its current model of success. Consequences of measuring GHG emissions with a focus on CO2 include driving manufacturing back into countries where it was previously outsourced and the development of distributed manufacturing systems within countries to minimize supply chain distances traveled simultaneously lowering GHG emissions.

Figure 5.1 Dashboards of the future

Introduction

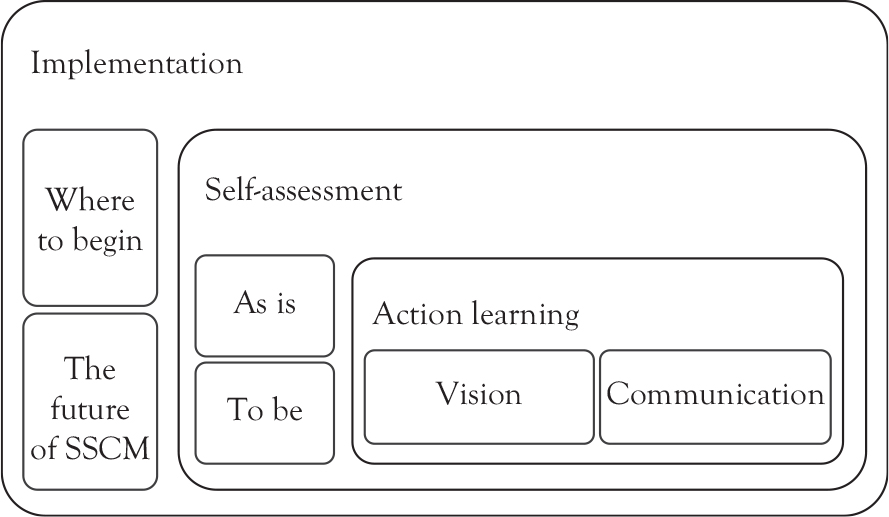

Motivation for the information presented in this book is a call for a better understanding of SSCM and the successful implementation of new programs. As defined early in Volume 1, SSCM is the integration of systems thinking and action into supply chain management that must include financial, AND environmental, AND social performance. These SSCM practices include stakeholder engagement, materiality, product/process design, life cycle assessment (LCA), materials selection and sourcing, manufacturing processes, waste, transportation of final products and services to consumers as well as end-of-life management of products and closed-loop systems. Systems thinking brings with it a more comprehensive approach to analysis that focuses on the way that a system’s constituent parts interrelate and how systems work over time.4 This definition of SSCM is positioned within the context of business models, frameworks, and tools for selecting and developing operations and supply chain management practices. While supply chain management calls for assessing and using information to make long-term decisions regarding supply chain strategy, having a strategy is not enough. Key to any successful strategy is the need to integrate suppliers and important metrics into processes management. Information in this chapter deals with how firms should implement SSCM. To integrate this paradigm into the long-term planning processes of a firm, we will next address implementation practices (see Figure 5.2) such as self-assessment, education, integration, vision, and communication, as they are all important for developing and delivering a SSCM strategy.

Figure 5.2 Planning and implementation architecture

The Future of SSCM

Before addressing what we see as the future of the sustainable supply chain, it is important that we return to the discussion of the various types of sustainability strategies introduced in Volume 1, Chapter 2. In this discussion, we pointed out that sustainability can be implemented in one of three major forms:

- Sustainability as Public Relations: This is an opportunistic approach—one in which the firm is not really committed to sustainability. Rather, it looks to any actions that it takes and sees if there is sustainability “angle” that can be publicized. Simply put, this is spin management with a sustainability perspective.

- Sustainability as Cost Minimization: With this approach, management focuses on the waste aspects of sustainability. Pollution, one of the major undesired outputs found in systems that are not sustainable, can be regarded as a form of waste. Waste adds significantly more to costs than it does to revenue. Consequently, drawing on the various tools and procedures offered by Lean, the firm strives to reduce waste and ultimately cost by focusing on sustainability. While very attractive in the short term, we must ultimately recognize that the long-term attractiveness of this approach is limited. Diminishing marginal returns plays a role. Over time, we find ourselves spending more and more time, efforts, and resources on smaller and smaller returns.

- Sustainability as Value Maximization: Here, we see sustainability as linked to the firm’s strategy and as an integral element of its business model. With this approach, the firm is committed to sustainability because it enables the firm to offer more value to its key customers, The result is often higher revenues, not simply lower costs. Higher revenues, associated with market growth, are very attractive pulls for upper management.

As we move into the future, the first critical finding is that “sustainability as Public Relations” will become less viable. This prediction has a very high probability of taking place. First of all, customers are becoming far more knowledgeable, educated, and critical when it comes to sustainability. Smart phone apps such as GoodGuide (goodguide.com), or websites such as sourcemap.com provide a wealth of transparency and visibility like never before. They can look up companies and their activities and can read what others have written about these companies. Unless they see a viable, well-thought out strategy underlying the sustainability announcements, customers are likely to dismiss these claims.

This factor was recently driven home to one of the authors, who were asked to do a sustainability presentation for a major company located in the Midwest. In preparing for this presentation, the author decided to select certain companies that he viewed as exemplar in terms of sustainability reporting. One of the firms selected was Unilever; the other was an internationally known manufacturer and distributor of consumer beverages. In presenting the various reports generated by this latter company, the author was challenged by one of the participants. The participant remarked that the statistics and the presentations provided by this company were really defensive in nature. After all, the participant argued, this company was primarily selling sugared water, which was adversely affecting health worldwide. The reports did not address this problem; rather, they seemed to argue that any adverse health issues should be weighed in terms of the other benefits that this company was creating. To this participant, this was simply window dressing and it should be dismissed. What was interesting was that this position was shared with other participants. To these participants, what they saw was sustainability as public relations and they rejected this position.

The second factor is that of the “CNN effect.” The CNN effect is a notion that is frequently heard by researchers and writers working in the humanitarian/disaster relief area. What this means is that in today’s world, the media is no longer willing to accept any claims made by firms. Rather, every claim will be investigated and, if found to be false or unsupported, the negative results will be communicated quickly through print, television, on the radio and over the Internet. In other words, when a firm screws up on sustainability, it is immediately evident to the rest of the world thanks to a demanding and intelligent press/media. Apple has experienced this effect first hand as have other companies such as Nike and the Body Shop.

The third factor is the changing nature of the consumer basis. Increasingly, the major consumer driving force of the past, the baby boomers, are dying out (both literally and figuratively) and they are being replaced by the millennials. The common definition of a millennial is any person born between 1982 and 2002. These consumers began arriving into the marketplace in 2003. What companies are quickly finding is that these consumers see things differently as compared to the baby boomers.

Specifically, these consumers brought with them a new set of attitudes. It was not enough to offer these buyers a good product. What these consumers wanted were products to be responsibly produced. Furthermore, they have a very broad view of sustainability—one that goes beyond pollution. They are concerned about whether the companies they buy from offer real opportunities for advancement and promotion in the management for women and minorities. They are also technologically savvy—they can use vehicles as the Internet and social media to track and evaluate how companies are actually performing. If a company is found to be deficient, then this finding can be quickly dispersed to other interested millennials. Since this market was the growth segment, these issues have to be addressed with real action.

The second critical finding is that we can expect to see sustainability and SSCM as continuing to expand and drive business value. That is, we expect to see more and more firms integrating sustainability into their business strategies and, more importantly, into their business models. Why? There are several reasons for this shift. First, firms such as Ford, IBM, Unilever, Walmart, and other innovators and Early Adopters have already provided the proving grounds for proof of more efficient and effective value creation. For a synopsis of studies showing the business case for sustainability see “Sustainability Pays,” a project by Natural Capitalism Solutions.5 Consequently, the risks of being a first mover (i.e., moving first and picking a development that ultimately does not succeed, e.g., picking Betamax over VHS in the tape wars) have been significantly reduced by the efforts of these companies. Second, customers are now increasingly expecting sustainability as part of the value proposition. Third, if we want to maintain our competitive positions in the marketplace, we are now expected to respond by matching the major sustainability-based moves initiated by our competition.

In addition, the various forces impacting SSCM are long term, persistent, and significant. These forces are due to resources (resource scarcity and increased competition), customer demand, government (especially in the developing countries—as many want what they see in North America and Europe), and transparency. Regarding this last dimension—transparency—consider the impact of technology. Increasingly, we now recognize that we are living in a world of smart devices (smartphones, sensors in cars, smart watches, and products). These smart devices are now collectively referred to as the Internet of Things (IoT). It is now estimated that there will be over 200 billion smart devices by 2020. IoT is making the development of true supply chain visibility both feasible and cost effective. The combination of these factors is changing the playing field for sustainability.

In the current and future business environments, sustainability must be seriously considered. When effectively used, it can become an order winner; when poorly deployed or overlooked, it will be an order loser.

Will everyone become sustainable? The answer is no! In reflecting on this question we return to the importance of systems design and the Crossing the Chasm model. Some firms are Innovators and Early Adopters while others are Laggards; yet the majority of organizations fall somewhere in between. Some have already said that sustainability has neared a tipping point.6 How we will respond to the sustainability challenge depends on the type of managers we are and the type of firms in which we operate. A key aspect of this is organizational culture and the ability of management to implement new business paradigms.

Will I succeed? Not necessarily! But by understanding current processes and trying at least, you increase your chance for success. Remember—not trying = 0 chance for success. The information outlined in this book provides guidelines, frameworks, performance metrics, and standards that increase the probability of a successful outcome. Sure, you can take a narrowly focused approach to SSCM, define it, and maybe do just enough to be able to market some of your actions. To do so comes with a reality check from the point of view of your competition and stakeholders. Deming’s admonition, made for TQM, equally applies to the SSCM. He was once approached by a CEO who asked if he, the CEO, had to do everything that Deming had identified as being important and necessary. “No,” Deming replied. “You don’t have to do everything. Survival, after all, is not mandatory.”

Planning and Implementation

If we are to be successful with sustainability, it must become part of our day-to-day life, business model, our core values, and those of our supply chain. It must become part of our strategy and our corporate culture. This is a major challenge and it is one that we must recognize. Although strategic planning is entrenched deeply in the minds of corporate managers and market planners, SSCM will need to be diffused throughout the organization and across functions. Before SSCM can truly affect long-range decisions at the corporate level, decision makers must first understand, develop, and implement strategic planning more effectively at the department level. The corporate planning process must incorporate more effective, integrative, and coordinating mechanisms among the various components of the strategic planning process. The end result must ultimately enhance a firm’s ability to create value.

Any manager typically can see only part of the picture when looking at a supply chain. A few decades ago, researchers found purchasing personnel, especially at higher levels, do not spend a sufficient amount of time and energy on such important strategic activities as external monitoring.7 Unfortunately, this is still true in some late adopting and Laggard firms today. Unless high-level personnel concentrate to a greater degree on these external relationships they will not be able to have a positive impact on a firm’s strategic planning process.

We are now more aware of the social/cultural side of change and of the organization. What we have yet to address is the issue of culture and implementation. Through decades of empirical research, researchers have established numerous relationships between organizational culture and performance. Organizational cultures (i.e., collaborative, competitive, creative, and controlling to name a few) will have different approaches to structure their solutions and thus account for the important role that culture plays in the planning and implementation of new initiatives. Next, we will use action learning as one applied approach to tackling the implementation process.

Action Learning

There is a growing need to unlock the capacity for all personnel to contribute to problem solving. One means of identifying and integrating sustainable supply chain practices is through action learning. This applied approach to problem solving and learning is defined as “a personal and organizational developmental approach applied in a team setting that seeks to generate learning from human interaction arising from engagement in the solution of real-time (not simulated) work problems.”8 We know from previous chapters that teams are important to the success of any initiative, yet we all have the same question at the beginning of a new initiative.

How do you begin this journey? First, begin by understanding why you want to become sustainable. Do not blindly jump into SSCM thinking everyone will understand or see this opportunity the same way you do. It has taken over forty years for the environmental movement to get to where it is today. Your efforts should be purposeful and focused. Understand what you want out of sustainability and why you are pursuing this initiative (e.g., efficiency, waste reduction, revenue, risk reduction, flexibility, brand image).

Second, create a compelling argument for change. Understand that people in your organization are being asked to undertake change almost every day. They have been asked to undertake the TQM journey, implement Lean Systems, become more innovative, and to transform their business relationships from being transactional to being collaborative. Your call for sustainability is simply another demand being added to the pile of demands. This situation is not simply good or bad; it is simply business reality. Because countless demands have failed in the past or have been replaced by the new “management revolution of the month,” many organizational members have adopted a very simple but effective approach—nod your head as if you understand, listen politely, and then keep doing what you are currently doing that works.

If we are to overcome this management inertia, we must first build a compelling business case. There are two aspects to this business case that must be emphasized. The first and one that most people focus on is to provide a quantitative assessment of costs and benefits that demonstrates the significant advantage offered by sustainability. Yet, you have to do the second part—to demonstrate to the participants that what is currently being done no longer works. We have to effectively discredit the current practices. Unless we do this, people will simply return to what they used in the past. Better the devil that you know rather than the devil that you don’t know.

In developing this business case, education and understanding will be key to this undertaking. Start with an understanding of the “As Is” state of your current operations and supply chain practices. Apply known process-mapping approaches, standards, and make sure you have the necessary tools as outlined in Volume 1, Chapters 4. Secure top management support and make sure you have the time, resources, and commitment necessary. An audit of current practices and self-assessment will be just the start of the implementation process. With an understanding of current operations and supply chain practices, you can then start making decisions regarding how you will lead your given organization on the implementation of SSCM based on evidence and opportunity identification.

Assessment at the Macro and Corporate Levels

This book argues that the stage has been set for the extension of environmental management to SSCM within many original equipment manufacturers and transportation providers already driving new forms of business value. Have we gone far enough? The answer, not yet. To truly begin addressing this challenge, we need to assess events and performance at both the macro level (fit with strategy level) and the micro (performance within the firm level) level.

Self-assessment at the Strategic Level

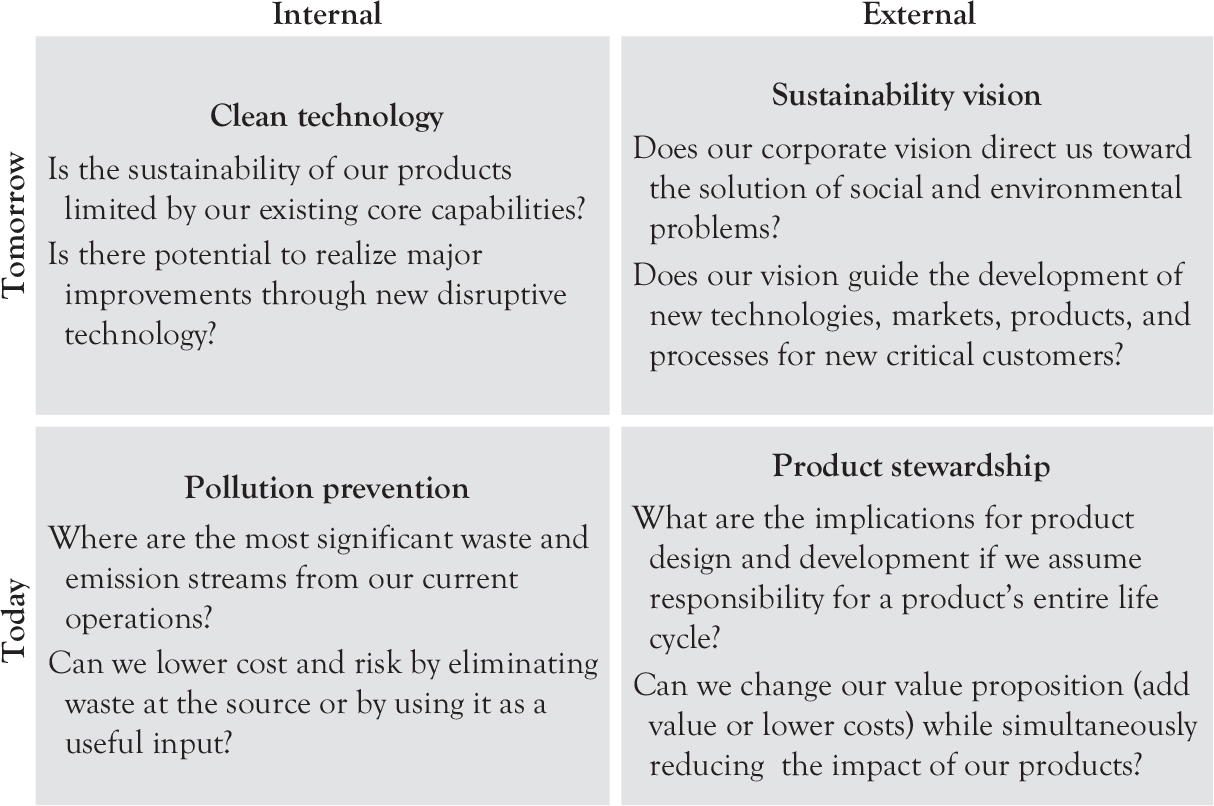

One way to assess how far we have to go would be Hart’s Sustainability Portfolio tool found within the Harvard Business Review article, “Beyond Greening” can provide insight as to how far we still need to go to reach tomorrow’s potential (Figure 5.3). This tool can help you determine whether your current strategy is consistent with sustainability. This process involves a macro level self-assessment AND rating of your organization’s capability in each of the four quadrants by answering the questions within each. Modern portfolio theory would suggest business managers can construct this portfolio to maximize expected returns given the level of risk and Hart suggests a balanced approach to maximizing returns.

- Many organizations will find themselves primarily in the lower left quadrant, with an emphasis on pollution prevention. Without investments in new technologies, core capabilities, and new markets, the company’s environmental strategy will be vulnerable to market forces in the future.

- A portfolio with high scores in the top half can be construed as a vision without the capabilities to implement it. Internal strengths are indicative of innovation, while external strengths are aligned for anticipating new markets and sustainable development.

- A portfolio with higher scores in the left half represents an ability to address environmental issues through internal process efficiency and new technology. A focus on today is efficient but will miss out on the innovation of tomorrow.

- A portfolio with higher scores in the right half can overlook facility-level operations, core capabilities, and technology as operations will be causing more environmental and social impact than is necessary. A focus on today can be construed as a right to operate aligned with industrial ecology.

Figure 5.3 The sustainability portfolio

Source: Adopted from Hart (1997).

Hart’s macro level assessment is a good place to start when wanting to understand the larger picture and potential vision of SSCM.

There is now a new opportunity to look at the primary enablers of a value chain, this being the transportation industry’s financial, AND environmental, AND social value maximization. Why the transportation industry? New evidence has shown that over 80 percent of this economic sector’s ecological footprint is captured within direct carbon emissions and purchased energy inputs.9 With new information now available to them, firms across industries are starting to research the life cycle implications of their products and services that include transportation, and the use of products. Decision makers in those sectors should also think about the implications of measuring and managing their supply chain’s sustainable value added (SVA). Why? Total supply chain emissions consist of the majority of a manufacturing firm’s carbon footprint,10 which has typically only been looked at as a cost of doing business. This is only one measure of supply chain performance. In the near future, performance will include multiple measures of financial, AND environmental, AND social performance taking firms beyond pollution prevention and into the realms of clean technology, product stewardship, and a sustainability vision.

Self-assessment at the Corporate Level

Assessment at a micro level enables understanding of business processes and elements of your business model (capabilities, key customer, and value proposition). We suggest internal assessment of your own function first. Start with a narrow scope or processes to assess. With an understanding of how you would approach this process from a single functional perspective, then move toward cross-functional involvement through the assembly of a team. This assessment process, when part of action learning, is best facilitated with the help of a cross-functional team. The audit and assessment process (for a single function or across functions) should have the goal of understanding:

- Performance metrics currently in use, assessment of pollution prevention.

- Best practices and integrated management systems.

- Interrelationships of processes and systems as a whole.

- GHG emission inventory and carbon footprint.

- Sustainable value added.

- Integration and design opportunities.

- New goals and metrics relative to sustainability opportunities and standards.

- Vision of the “To Be” state (carbon neutrality, zero emissions) and a sustainability vision.

- Integration into the day-to-day life of the firm.

Approach the self-assessment, opportunity identification, and change management through the use of Juran’s Universal Breakthrough Sequence (UBS) reviewed in Chapter 4. As we know, Juran developed a systematic approach to TQM. The goal, in developing this approach, was to make quality into a habit. For quality to become a habit, it had to be the result of a repeatable process. This UBS process logic applies equally well to sustainability as a focal point as it applies to the proven benefits of TQM. The steps in this UBS process are within a context of self-assessment and proven practices including:

- Proof of the need.

- Project Identification.

- Organization to guide each project.

- Diagnosis—breakthrough in knowledge.

- Remedial action on the findings.

- Breakthrough in cultural resistance.

- Control at the new level.

Outcomes of the self-assessment allow a team of internal managers to learn more about SSCM impacts across functions and its potential within the organization. Teams need to select and implement the most cost-effective technologies and practices. There is one caveat to the assessment. To help ensure a better outcome, assemble the team and perform the assessment without adding more responsibilities to team members’ existing workloads. Thus, find a balance with the new initiative and lessening of prior responsibilities. We can all find some less valuable responsibilities we would like to get rid of, now is your chance.

Self-assessment at the Micro Level

Much of the traditional view of change management has focused on the prior two levels. That is, it is assumed that if the need for change is accepted at the macro and corporate levels, then the rest of the organization will go along with it. While this perspective is attractive (because it deals directly with the need for things such as top management support), it is also short-sighted. It assumes that the other organizational levels have little or no impact on the acceptance and diffusion of sustainability; it also implicitly assumes that there are no interactions between the levels. Both of these assumptions are wrong.

To be successful, sustainability and its need must be embraced by the people charged with deploying it. It must be accepted by the people who work on the shop floor. It must be embraced by the organizational buyers when contracts are awarded and when performance of the supply base is evaluated. It must be embraced by the packaging engineers when they design new packaging. It must become part of the organizational culture. It must become something that the people charged with deploying sustainability do naturally and consistently—even when the boss is not around. This is one reason that exemplar organizations such as Unilever are so successful when it comes to sustainability.

As pointed previously in this book on implementation, it is wrong to assume that users are additive thinkers. That is, when introducing sustainability, managements brings in new approaches and then proceeds to show that these approaches not only work but that they can work in their organizations. It is then assumed that the users will add these tools to the existing set and use them when necessary. The problem with this approach is that it is wrong. Users tend to be substitutive thinkers. That is, they will only drop existing tools and approaches when it is convincingly shown that the current ways of doing things is wrong and doomed. That is why crises are so effective—they show everyone in the organization that the current approaches are wrong and that they are no longer working. Unfortunately, the problem with crises is that there is a lack of time and a lack of resources needed to bring about change.

What this means is that when beginning the sustainability journey, management must spend time understanding the problems being addressed in the deployment areas and they must understand what tools are being used and why they are being used. Next, management must develop a strategy for convincingly discrediting the existing tools, if they are not in line with the goals of sustainability. Once the existing tools have been discredited, the new tools can be introduced. These will be more likely to be accepted because they are filling what has become an organizational vacuum.

Finally, it is important to recognize that since many of these tools and approaches are new, management must expect failure and it must be tolerant of failure. It must differentiate between smart failures and dumb failures. A dumb failure is when the employee does something that they have been told not to do—they essentially break the rules. Such failures should be punished if appropriate. Smart failures, in contrast, occur when the rules and procedures are implemented correctly and something unexpected occurs. Such failures should not be punished. If punished, the result is a clear message to the organization and its suppliers—DO NOT EXPERIMENT; DO NOT FAIL. When this message is sent out and accepted, there is no experimentation. Experimentation is critical if we are to be successful. Remember what turtles teach us—a turtle only advances when it sticks its neck out.

Action Items

One outcome for the assessment team should always be to educate others as to the meaning of, and opportunities for SSCM. One purposeful approach to educating yourself and others is found within the end of chapter Action Items (AIs). Each chapter in this book synthesizes information from the field and provides the reader with actionable insight for continuous improvement. AIs at the end of each chapter will help to identify and prioritize opportunities for action learning and organizational improvement.

Have the assessment team provide independent assessment from their own functional perspective as to what is important and why. Use our online assessment AIs to provide summary information of your assessment and within-industry comparisons as this is available to you at no cost. When the team has results, share the insight within the team and then widely within the organization. Create a sense of urgency and work toward quick wins where the results of the initiative(s) can be shared across functions.

Top Management Support

Support from the top is the key to any initiative. The need for SSCM project is recognized by everyone in the organization when it is evident that this initiative is being driven by top management’s desire to improve the firm’s competitive position or as a top management response to specific threats to the firm. In some cases, top management will initiate the program directly. In other cases, ad hoc groups already working on supplier issues initiate the need for a program. The recognition of the need for an initiative is then transformed into a set of organizational and sustainable objectives. These objectives can include the hiring of new talent from top MBA programs who are signatories to the United Nations Principles for Responsible Management Education (PRME), ranked by the Aspen Institute’s Beyond Grey Pinstripes or the Corporate Knights Global Green MBA ranking of graduate business programs integrating sustainability within curriculum or highlighted in the Princeton Review’s guide to green colleges. Objectives should be broad-based and flexible while balancing the ability of personnel to try new things and fail without retaliation. A culture of innovation cannot come about through a fear of failure. Finally, top management can make the UBS better established as the approach to SSCM opportunity identification and execution as part of internal reward and incentive systems.

Vision and Goals

A vision and goals should be the objective of the assessment team, including the steps and suppliers to include in this change process. A difficulty in doing this comes from how people in different parts of the organization talk about initiatives. Top management tends to focus on the bottom line while line workers talk about materials and resources. Thus, a vision helps to get people focused on the “To Be” state of the future. To this end, the opening chapter of the book Natural Capitalism11 begins with:

“Imagine for a moment a world where cities have become peaceful and serene because cars and buses are whisper quiet, vehicles exhaust only water vapor, and parks and greenways have replaced unneeded urban freeways. OPEC has ceased to function because the price of oil has fallen to five dollars a barrel, but there are few buyers for it because cheaper and better ways now exist to get the services people once turned to oil to provide.”

The authors go on to talk about buildings that generate more electricity than they consume, atmospheric CO2 levels decreasing for the first time in 200 years, water leaving facilities being cleaner than when it entered, and industrialized countries reducing resource consumption by 80 percent while improving the quality of life. This is only part of the first paragraph, yet it provides a vivid vision of the future and through backcasting (application of The Natural Step) from that vision to where we are today, it also provides an opportunity for decision makers to pause and think about how business processes and whole supply chains will have an impact on the Natural Capitalism vision.

With the help of top management, and the results of the assessment team’s findings, the vision should be communicated widely, and aligned with training and resource allocation to make the initiative successful. The shared vision and performance metrics will bring the supply chain together as stakeholders will want to know how to create value while aligning processes and practices with the vision.

Sustainability is part of a mixed bag of outcomes … innovation, waste reduction, culture, visibility, value creation, and transparency across a supply chain. It is imperative to understand how it aligns with other systems and outcomes the organization is pursuing.

Three additional points must be reinforced before we leave this discussion of how to implement SSCM. First, involve your supply chain but do not expect the supply chain to believe that you are committed to sustainability until they see significant, verifiable evidence of progress within your organization.

Second, when undertaking change, first allow your people the opportunity to state their reservations and concerns. A great deal of organizational resistance to change is due to the fact that the people have valid concerns that they feel they are being ignored. Listen, understand, and work with the people to deal with these concerns.

Third, develop and maintain a sense of urgency. Often, these initiatives die because the people involved do not see them as being of high priority. Develop a timeline for change; identify and monitor milestones and progress; hold people accountable for results; report the good and the bad results; and be prepared to revise objectives and project timelines as events change. Develop and maintain an on-going pressure for change—a message that should be consistently delivered at all level of the organizations, beginning with the CEO. To this end, it is useful to look at what Unilever and Paul Polman has done—his timeline is a template that many firms should strive to emulate.

The future of SSCM, planning, and implementation all require management to take note of emerging trends and evidence of companies already engaged in these efforts. To this end, we have tried to revel how sustainability is becoming an order winner and competitive advantage for some.

Summary

The future of supply chain management will involve financial, AND environmental, AND social performance in addition to good governance practices throughout the life cycle of goods and services. As we have shown by the numerous examples in this chapter and previous chapters, innovative and early adopting companies are already driving sustainability internally and within their supply chains. With increased attention given to managing supply chain performance to an Integrated Bottom Line, there are frameworks such as the framework for strategic sustainable development (FSSD) (Chapter 2), and numerous practices and tools available to help you when planning and implementing SSCM.

Applied Learning: Action Items (AIs)—Steps you can take to apply the learning from this chapter

After reviewing this chapter, you should be ready to assess planning and implementation opportunities. To aid you in this assessment, please consider the following questions:

AI: Is the sustainability of our products limited by our own capabilities?

AI: Does our vision direct us toward solving social and environmental problems?

AI: Does our vision guide the development of new technologies, products, or processes for critical customers?

AI: What goals and metrics are already in use, and what new goals should be utilized relative to sustainability?

AI: What level of support can you garner for sustainability initiatives from top management?

Carbon Disclosure Project & Accenture (2012). Reducing Risk and Driving Business Value. Supply Chain Report.

Hart, S. L. (1997). Beyond Greening: Strategies for A Sustainable World. Harvard Business Review. 75(1)p. 66+

Laszlo, C. (2015). Sustainability for Strategic Advantage: The Shift to Flourishing Stanford University Press and Greenleaf Publishing.

Orts, E., & Spigonardo, J. (2012). Greening the Supply Chain: Best Practices and Future Trends, Initiative for Global Environmental Leadership.

Schein, E. H. (1999). The Corporate Culture Survival Guide: Sense and Nonsense about Culture Change. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass.

1Stika (2010).

2Mohin (2011).

3Deloitte (2011).

4Meadows (2008).

5Natural Capitalism Solutions (2012).

6MIT Sloan Management Review and Boston Consulting Group (2012).

7Spekman and Hill (1980).

8Raelin (2006), pp. 152–156.

9Mathews et al. (2008).

10Huang et al. (2009).

11Hawkins et al. (2008).