The previous chapters provided you with a profound understanding of the three most important digital technologies that foster the digital transformation of private and public organizations: quantum computing, blockchain technology, and artificial intelligence. The different applications and use cases described exemplarily at the end of each chapter revealed that each technology not only allows for optimizing existing products and services but also for exploring new growth opportunities in mature and entirely new markets or environments.

Chapter 2, “Quantum Computing,” introduced quantum computing as a transformative force for organizations that employ (super)computing for highly complex optimization, modeling, and simulation problems. We also learned about the far-reaching potential of blockchain technology and its unique capability to deploy trust in untrusted environments and enable cryptographically secured value transfers between two or more trading partners. Last but not least, we studied artificial intelligence as the underlying technology for big data analytics, machine learning, and other applications that allow for monetizing large datasets and implementing data-driven – and thus more transparent and objective – decision-making processes.

The eight key dimensions of digital transformation

But before we discuss this digital action plan along the eight key dimensions of digital transformation in detail, it is instructive to have a look on the digital transformation of Microsoft to highlight certain similarities: In 2011, Microsoft was a tired company. It faced a range of severe competitive threats spawned by the Internet and had run into serious antitrust scrutiny, both threatening its existing business model. Their traditional software business was about shipping software CDs around the world to install Microsoft DOS, Windows, and Office on every computer. Besides exploiting this classic software business, Microsoft had been experimenting with a small cloud computing service called Microsoft Azure at that time for delivering software and services on demand. This explorative project was, however, widely considered a nonprofitable failure, which is why Microsoft was focusing on exploiting its legacy business instead. But Satya Nadella – the head of Microsoft’s Server and Tools group at that time – disagreed with this strategic assessment and was filled with conviction that cloud computing will be the future of Microsoft. Three years later, Satya Nadella succeeded Steve Ballmer as CEO and reinforced his strong vision in his first email to his employees by writing: “Our industry does not respect tradition – it only respects innovation. [...] Our job is to ensure that Microsoft thrives in a mobile and cloud-first world” [1]. In order to bring his clear and compelling vision to life, he rearchitected Microsoft’s software delivery process in the following years by transforming the underlying traditional business model from putting software on computing hardware on premise to delivering software-as-a-service via cloud computing on demand. For this purpose, Satya Nadella scaled up the digital pilot project Azure by adding more and more cloud-based applications to it, such as Microsoft Office 365 and Microsoft Dynamics, an enterprise resource planning and customer relationship management software. His strategy gained further traction with the acquisition of GitHub in 2018, a very popular online repository for open source software projects and tools. Guided by his clear vision and strong conviction about the future of cloud computing, he successfully transformed Microsoft into a cloud software company. In consequence, Microsoft’s stock prize tripled in value during the first three years of his CEO tenure. But this was not the last digital transformation on his agenda. Inspired by the famous “AI-first” announcement1 of his friend Sundar Pichai [2], the CEO of Google, Satya Nadella adjusted his vision in 2018 and laid out plans for Microsoft’s next digital transformation into an “intelligent cloud and intelligent edge” computing provider [4], who also leverages the three digital support technologies introduced in this book. He later noted in an interview that “AI is the run-time which is going to shape all of what we do” [5] – a digital business strategy that Microsoft is pursuing with its Azure cloud computing platform very successfully until today.

What can we learn from Microsoft’s digital transformation journey? The foremost important lesson to learn is that success with a novel product or service does not come without any entrepreneurial and thus financial risk. Amazon, for example, has admittedly had some spectacular failures over the years worth billions of dollars [6], such as Amazon Auctions, zShops, and its Fire Phone that became the basis for its highly successful products Amazon Marketplace and Amazon Alexa/Echo later on, respectively. Jeffrey Bezos, the founder of Amazon, famously noted in this context in his 2016 Letter to Shareholders:

[...] failure and invention are inseparable twins. To invent you have to experiment, and if you know in advance that it’s going to work, it’s not an experiment. Most large organizations embrace the idea of invention, but are not willing to suffer the string of failed experiments necessary to get there. Outsized returns often come from betting against conventional wisdom, and conventional wisdom is usually right. Given a ten percent chance of a 100 times payoff, you should take that bet every time. But you’re still going to be wrong nine times out of ten [7].

New business ideas are always hypotheses about the future and thus a hunch of what customers may need tomorrow. Most executives therefore often hesitate to adopt new technologies and transform their business as they potentially threaten existing processes, businesses, and revenue streams.

The second lesson to learn is that digital transformation is a journey. This journey starts with developing a clear and compelling vision, a strategic objective that creates high commitment among the employees, guides an organization along its transformation, and makes all shareholders think that they are part of an exciting adventure – “the leader’s role is to define reality, then give hope” to say it with the words of the legendary French emperor Napoléon Bonaparte. The leader’s vision picks up key trends in business and society and provides a clear view on how they translate in an overall operating model capable of creating value for customers and other stakeholders.

The third lesson to learn from Microsoft is that a digital transformation always starts with exploring new technologies in pilot projects that can occasionally scaled up and rolled out to transform the entire organization ultimately. Digital transformation does not stop at an organization’s hierarchical structure, but also involves major changes with respect to strategy, culture, employees, and other core capabilities of an organization. This is not surprising on closer inspection since digital transformation is enabled by digital technologies that ultimately rely on data processing facilitated by some sort of algorithm, program, or software. But depending on its complexity, it is almost impossible to develop and directly deploy a software to customers without any bugs. This is why software development – and digital technologies alike – promote an iterative approach to product innovation and development that is enabled by an open innovation culture and agile ways of collaboration among employees. This is why digital transformation impacts all dimensions of an organization and is much more than using digital technologies to digitize formerly paper-based processes.

When comparing Microsoft’s digital transformation journey with the ones of other companies, you will quickly notice that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to digital transformation, unfortunately. However, the following framework describes digital transformation in terms of eight key dimensions and may well act as a good guidance for your own digital transformation journey. It focuses on the digital transformation of incumbent companies, who need to continue running an established legacy business during their digital transformation journey.

5.1 Envision a Digital Strategy

The main purpose of every organization – private or public – is to create, deliver, and capture value. This value originates from two concepts. The first one is the business model , which defines how an organization creates and captures value in economic, social, cultural, or other contexts.2 The second is the organization’s operating model, which defines the particular way an organization delivers value to its customers – the “plan to get it done” if you wish. In other words, the business model defines the theory while the operating model captures the practice of an organization’s value creation process. Digital transformation is about rethinking and rearchitecting both the business and operating model by leveraging the power of digital technologies. It usually targets either (1) an increase of the operational excellence by streamlining internal processes or (2) an enhancement of the customer experience [8] to transform a traditional to a digital business and operating model.

5.1.1 Envision a Digital Strategy: Develop a Digital Business Model

Historically, the process of envisioning a successful business model capable of creating a sustainable competitive advantage3 was dominated by two approaches: (1) market positioning and the (2) resource-based view of an organization. The first approach involves finding an (industry) sector with high entry barriers and differentiating products and services from competitors. The second approach leverages an organization’s rare and valuable assets and capabilities, such as patents or highly specialized machinery, that are difficult for competitors to imitate. Given the increasing competition from digital business models, both approaches seem to be inappropriate today since digital organizations create value through platforms and networks rather than physical goods and infrastructure.

Hence, the best way to envision a digital business model is by starting with a customer-centric view and aiming to delight customers with a better customer experience. An insightful methodology to better understand your customers including their consuming behavior and motivation is a customer journey, an in-depth step-by-step analysis of the experience a customer goes through when using a certain product or service [11, 12]. Throughout a customer journey, the customer is at the “center of the universe” as it starts with the customer rather than a product or service. It has been used successfully by numerous organizations over the past couple of years to identify unmet needs and other sources of customer dissatisfaction. Both insights are very valuable as they reveal the strengths and weaknesses of existing products and services and thereby open up new business opportunities. The next step toward envisioning a digital business model is about putting the different insights derived from the customer journey together and asking yourself how the customer experience can be improved and which (novel) products and services are required to do so. Amazon, for instance, is admittedly conducting customer journeys frequently to deliver the very best customer experience in retail.4

Clayton Christensen, the renowned Harvard economist we know from the introductory chapter of this book, developed a very popular approach complementary to customer journeys for capturing the customers’ needs and deriving a corresponding business model. When asking himself why a customer purchases a certain product and not another one, he realized that customers do not really buy products but rather hire them to solve a specific problem. In other words, customers hire products to get a job done, which is why his concept is nowadays referred to as the customers’ job to be done [14]. The job to be done has two dimensions: (1) a functional dimension, which measures if the job to be done has been completed, and (2) an emotional or social dimension that describes how it feels to own and use a certain product or service. Consider buying an electric vehicle, for instance. The functional job to be done is being mobile and getting from one point to another with zero emissions in this case. The emotional and social side of it may be about showing everybody that one is at the cutting edge of technology or another nonmeasurable aspects of the electric vehicle, such as social status and (financial) well-being. According to Clayton Christensen’s famous disruptive strategy theory [15], a successful business model centers around the customers’ job to be done perfectly, which is why this is often depicted as the “north star” in innovation. In other words, anything that allows customers to get their job done better is innovations that organizations should focus on as they provide great growth opportunities for existing products or services. Putting the customer to the “center of your universe” is thus an important prerequisite for advancing an existing or envisioning a new business model and its underlying strategy.5

It is important to bear in mind in this context that only a few lucky companies start off with a digital business model that ultimately leads to success. The majority of them initially explores different opportunities with an emergent strategy until they find something that really works. This is why you should be prepared to experiment with different digital technologies and opportunities, ready to pivot, and continue to adjust your approach until you find a veritable one – the emergent strategy becomes the new deliberate strategy at this point.

To summarize it with the words of Clayton Christensen, “most products fail because companies develop them from the wrong perspective. Companies focus too much on what they want to sell to their customers, rather than what those customers really need. What’s missing is empathy: a deep understanding of what problems customers are trying to solve” [52]. I hope that the insights gained from these considerations will inspire and help you to envision a digital business model for your own digital transformation journey.

5.1.2 Envision a Digital Strategy: Derive a Digital Operating Model

Once a digital business model has been defined, it is important to ask yourself about how you are going to deliver value to your customers and which operating model best supports this value creation process. This is the point where digital technologies come into play. The best way to understand the characteristics of digital operating models is to compare them to traditional ones that are not based on digital technologies and centered around data. The fundamental difference between a traditional and digital operating model arises due to the particular way it leverages data. Traditional operating models use data as a necessary evil to support their operations without deriving economic value from them. As the number of products, services, customers, and the amount of data associated with them increase, traditional operating models are ultimately limited by their inability to manage complexity. For traditional business models that are not centered around data, it simply becomes impractical and too costly at some point to achieve data coherence6 across the organization. This is particularly challenging if the different divisions evolved into functionally separated business units over time with their own databases and legacy systems. The distribution of data to decentralized databases implies that decision making in traditional operating models is often based on information intransparency and thus on incomplete and inadequate assessments of decision options.

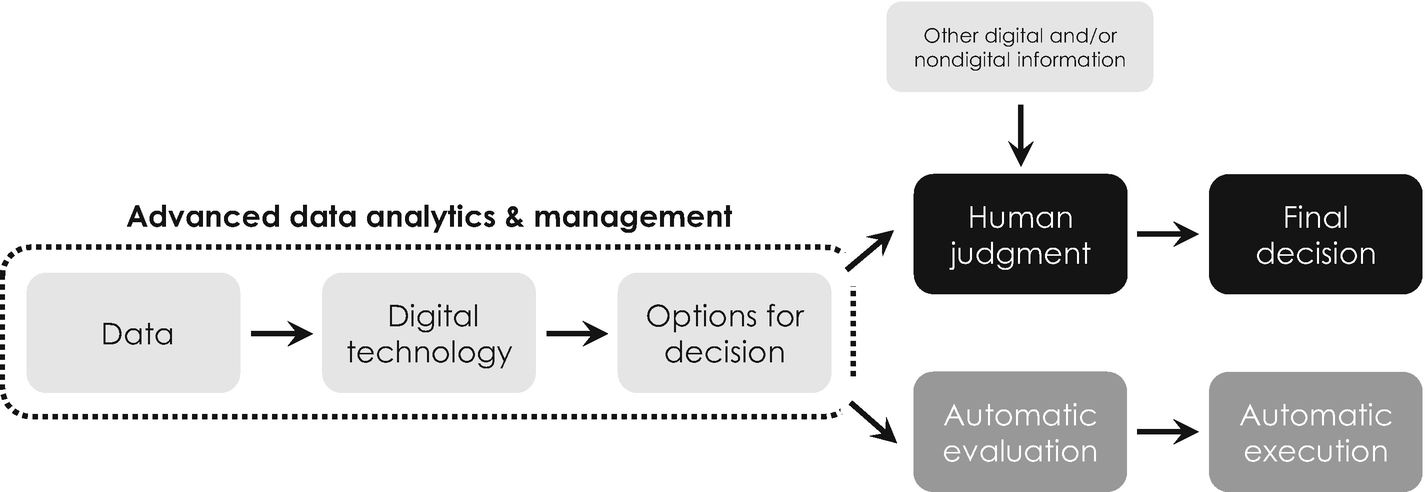

A data-driven decision-making process combines advanced data analytics based on digital technology and human intelligence. Human judgment (black) continues to play a central role in the overall process. Generalized from [9]

Furthermore, a digital operating model embraces the advantages of exponential scale, scope, and learning associated with digital technologies. Scale in this context refers to delivering as much value to as many customers as possible at minimum cost. Scope describes the range of activities, that is, the variety of products and services, a company offers.7 Digital learning determines an organization’s ability to continuously improve and innovate its processes, products, and services iteratively.

5.2 Select the Right Technology Stack

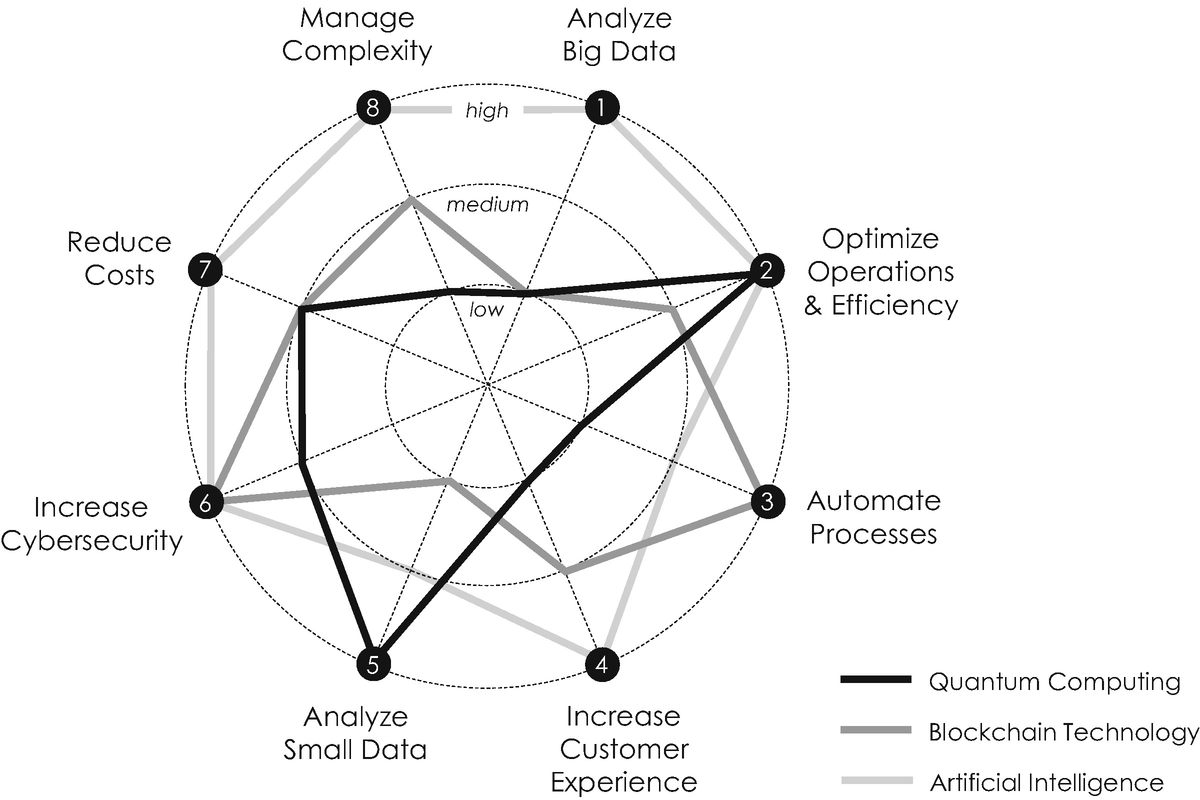

Digital property spider that rates the relative impact of different support technologies on selected domains of digital transformation on a scale between low and high

But independently of which digital technology stack you are going to use, you may either consider (1) building up your own digital capabilities in-house or (2) collaborating with external partners and cloud computing vendors. The first option is best if you aim to leverage your digital in-house expertise as a competitive advantage on a medium or long term. Otherwise, the best option is to subscribe to an external cloud computing service, which is less time consuming and invest intense in most cases.

Cloud computing refers to an actively managed pool of configurable computing resources including hardware and software applications that can be accessed via Internet on demand.

- 1.

Infrastructure-as-a-service or IaaS is the lowest service level with the highest customer autonomy. IaaS comprises all infrastructure building blocks, such as data servers, storage, networks, and virtual machines.8 All resources are provisioned and offered by the cloud vendor on demand within a pay-as-you-use pricing model.

- 2.

Platform-as-a-service or PaaS offers both ready-to-use hardware infrastructure and software development tools that enable users to build, test, and deploy their own cloud applications – all computational resources are administered and maintained by the respective cloud vendor in this service category too.

- 3.

Software-as-a-service or SaaS is the third service level and refers to a hosted cloud infrastructure that offers users completely developed software applications together with the required hardware on demand. Users can simply log in via a web browser, upload the data to be processed, and use different applications on the vendor’s software and hardware stack to process and analyze the data further. This service category is particularly interesting for users, who cannot build up their own resources, such as software, hardware, and personnel.

- 4.

Business-process-as-a-service or BPaaS allows to fully outsource stand-alone business processes, such as the payroll management (including the payslip entering and legal filings) and payment process. This service category is designed for companies that do not like to build up their own digital in-house capabilities and outsource particular business processes completely.

The four basic service class models of cloud computing services, namely, infrastructure-, platform-, software-, and business-process-as-a-service

- 1.

Performance: The superior performance of cloud computing services arises due to the synergetic centralization of supercomputers in large data centers. Due to their frequent hardware and software updates, cloud services offer very reliable disaster recovery mechanisms after cyberattacks and other failures of an organization’s IT system.

- 2.

Agility: Cloud computing services are very flexible since they can be scaled up and down as computational demand increases or decreases, a characteristic that became known as hyperscale. Some vendors do often refer to their service as elastic clouds in this context to highlight that their service dynamically determines the amount of resources required and automatically provisions the cloud infrastructure accordingly.

- 3.

Cost: In contrast to building up your own digital in-house capabilities, cloud computing services do also allow you to benefit from massive economies of scale by reducing required upfront investments for hardware and software. They may also reduce the total cost of ownership of your hardware and software infrastructure under certain conditions. This is why cloud computing is particularly beneficial for smaller companies that do not have enough financial and human resources to maintain their own data centers.

Most cloud computing vendors offer elaborately made web interfaces that allow for an easy configuration of the IT infrastructure and fast customization of tools for a particular use or business case. The development of more advanced software tools and applications does, however, require profound knowledge about some of the most common and mainly open source programming languages in data science, such as Python10 and R. The different commands available in programming languages are often grouped together in certain packages and libraries for convenience. The most important packages that can be used to implement the three digital technologies introduced in this book in your own organization are shown in Table 5-1 for your reference.

5.3 Digitize the Core

The selected technology stack provides the underpinning technologies to digitally transform the core of an organization. According to the “context vs. core” model11 proposed by the American business strategist and consultant Geoffrey Moore, the core is what creates a competitive advantage, differentiation in the market, and ultimately wins and retains customers. Context consists of everything else including finance, sales, and marketing. In his book entitled Dealing with Darwin [24], Geoffrey Moore illustrates this concept exemplarily by referring to the American golf champion Tiger Woods. Tiger Woods’ core business is golfing, and his context business is marketing. While marketing generates money, there is no marketing (the context) without golfing (the core).

The most important Python packages and libraries for data science, quantum computing, blockchain technology, and artificial intelligence

Digital Technology | Library Website | Package Description |

|---|---|---|

General Data Science | NumPy is a standard package for big data analysis and scientific computing that allows to define sophisticated arrays of numbers | |

Pandas, the “Python Data Analysis Library,” provides numerous tools for big data analysis and manipulation | ||

Matplotlib is a comprehensive library for plotting and visualizing data. It is often used in conjunction with NumPy and Pandas | ||

Quantum Computing | QuTip is an open source quantum toolbox for simulating the dynamics of open quantum systems | |

Qiskit is an open source library for the implementation of quantum computing software for research, education, and business | ||

TensorFlow Quantum is one of the latest libraries that has been released by Google’s research team in 2020 and allows for rapid prototyping of quantum machine learning algorithms | ||

Blockchain Technology | PyPi blockchain provides various tools for the implementation of a blockchain or coin | |

Artificial Intelligence | TensorFlow was developed by the Google Brain team in 2015 for experienced experts and allows for the easy implementation of machine learning algorithms including artificial neural networks | |

PyTorch is an open source machine learning library used that was released by Facebook in 2016 for the first time | ||

Keras was released by Microsoft in 2015 as an open source library for beginners that allows for building, inter alia, convolutional neural networks |

A very good example and role model for a digitized core is Microsoft and its business unit “Core Services Engineering and Operations” or CSEO.12 CSEO is at the heart of Microsoft and has more than 5,500 employees globally who work across a broad spectrum of the value chain ranging from releasing products and running retail stores to human resources. Its core mission is to build products and tools that empower employees to drive productivity in their particular roles independently of their business unit by connecting everybody within the organization to a central data catalog, common software components library, and shared algorithm repository. By digitizing its core, Microsoft can rapidly digitize, enable, and deploy digital products and services across all business units to drive efficiencies and innovative business outcomes for the entire company. In their 2020 bestselling book Competing in the Age of AI, the two American economists Marco Iansiti and Karim Lakhani at Harvard Business School call such a digital operating model that relies on a highly integrated modular software and data platform AI factory. Furthermore, they explain:

[...] while production was industrialized, analysis and decision-making remained largely traditional, idiosyncratic processes. [...] The AI factory is the scalable decision engine that powers the digital operating model of the twenty-first-century firm. Managerial decisions are increasingly embedded in software, which digitizes many processes that have traditionally been carried out by employees [29].

In other words, an AI factory captures decision making as an industrial process driven by big data analytics [30]. Data-driven decision making systematically converts information into valuable business predictions, insights, and choices to guide and even automate certain business processes. This is at the heart of digitizing the core of a company and implementing a digital operating model. Marco Iansiti and Karim Lakhani explain further:

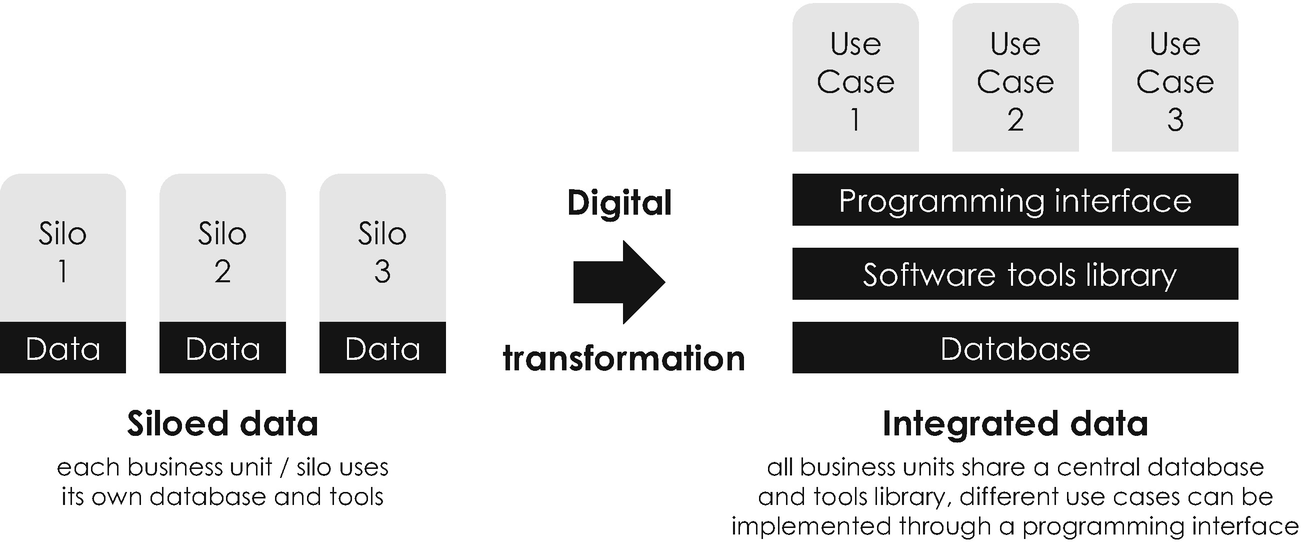

Digital transformation of a company’s operating model from a siloed to a highly integrated data architecture, in which previously siloed business units share a company-wide database. Graphics inspired by [29]

5.3.1 Digitize the Core: Create a Central Database

The first step of digitizing the core of an organization is to bring scattered data assets and distributed sources of information – often embedded in complex Excel spreadsheets [25] – together into an organization-wide and highly integrated database as a single version of truth. In this way, previously distributed and siloed data becomes structured big data that allows for comprehensive data analysis and processing as depicted in Figure 5-5 schematically. Integrating distributed data into a single database is particularly important since the real value of data arises due to the consolidation of different sources of information that has been collected for different reasons in different contexts by different business units. Just think about inventory stock data from the logistics and data about customer orders from the sales department. The consolidation of both sources of information creates transparency about their correlation and allows for optimizing inventory stock depending on demand accordingly – there are, of course, a range of other and less obvious examples for highly valuable data mergers as outlined in the previous chapter.

The most successful American media company – other than Google and Facebook – that has turned the convolution of distributed data and its interpretation by state-of-the-art real-time data analytics into a successful digital business model is Bloomberg, headquartered in New York City. Founded by the American businessman Michael Bloomberg in 1981, Bloomberg collects publicly available data from the Internet, such as official press releases and newspaper articles, and combines it with proprietary data gained from internal journalistic research. This convolution of data is analyzed by state-of-the-art digital technologies including big data analytics powered by artificial intelligence to derive further economically valuable business insights. This scarce information is then made available on Bloomberg Terminal [26], its core revenue-generating product for selling breaking business news to its institutional clients in the financial and information industry – quite often, those news impact stock prices and other (far-reaching) investment decisions.13

- 1.

Gathering: Collecting data from different internal and external sources of information including open source and third-party data

- 2.

Cleaning: Removing unwanted and unnecessary data without any use or value

- 3.

Normalizing: Converting the data into a set of standardized and predefined data formats for structured data (e.g., financial information, addresses, phone numbers, product information) and unstructured data (e.g., images, videos, audio files, social media tweets and posts)

- 4.

Integrating: Uploading the data to a cloud or data lake and making it accessible across the organization on the platform

This preprocessing can be very time consuming and needs to be considered in the overall time schedule of your digital agenda [28]. Nevertheless, this process is quintessential and inevitable since the quality of your data input critically determines the quality of the output as shown in the previous examples about artificial intelligence and its applications.

5.3.2 Digitize the Core: Develop a Software Tools Library

The central database is useless if nobody can access and use it. This is why digitizing the core of an organization secondly involves building a tools library on top of the database to deploy standardized software modules for analyzing the data kept in the shared database as shown in Figure 5-5. This software library is ideally accessed through a programming interface called “application programming interface” or API to be precise that allows different functional teams to easily adapt the standard software to their particular use case or business problem. The API should be designed to promote modularity and reuse of tools and algorithms by deploying different machine learning algorithms, software codes for running complex simulations on a quantum computer, or programming tools for operating a blockchain network, for example.

5.4 Identify Pilot Projects

The digital transformation of an organization cannot be finished over night from one day to the other, of course – it is a transformation journey rather than a sprint. Furthermore, incumbent organizations often need to continue running a legacy business while transforming organizational units and processes digitally. This is why it is crucial to start your digital transformation journey with pilot projects14 to create enthusiasm across the organization and drive its digital transformation. Innovative digital organizations, like Microsoft or Google, do always launch multiple pilot projects to increase the odds of getting a win.

Quick wins: In order to create enthusiasm across your organization and convince stakeholders to invest in building up digital capabilities, a pilot project ideally drives for early results and quick wins. A pilot project should typically take between 6 and 12 months prior to delivering its final result.

Scalability: A pilot project should be scalable so that it can be expanded to other business units upon its completion – poor scalability is the main obstacle most pilot projects suffer from.

Industry-specific focus: Pilot projects should focus on areas, where you are going to go at scale, earn money, and intend to create value on a long term.

Concrete business purpose: Successful pilot projects always focus on concrete, well-defined business problems or challenges to experiment on and learn from. This may be a balky internal process or a previously intractable problem that can now be addressed by digital technology. In other words, digitalization and digital transformation need to fulfill a concrete business purpose and are no fashionable end in itself.

In practice, pilot projects often face one major challenge that is in fact the main reasons why digital transformations fail [34]. This challenge is related to scalability – the second selection criterion – and called proof-of-concept trap. It refers to projects with an infinite pilot phase, which prevents the successful rollout of prototypes across the entire organization in time. Projects of that type turn into an endless “science experiment” that deploys overly complex solutions to showcase technical prowess even if a simple solution is available and may quickly return value. This is partly related to the fact that digital pilot projects often innovate in a very artisanal way without any established processes and delivery plans. The proof-of-concept trap can be avoided by focusing consequently on a concrete business purpose and making a reasonable compromise between innovation and industrialization. Successful pilot projects explore promising prototypes for innovation and concepts for their industrialization together at the same time rather than sequentially. This approach allows for a rapid rollout of successful features as soon as the first simple prototype version of a product or service has been established – just think about Tesla’s autopilot and its active learning strategy discussed in the previous chapter, for instance.

Vittorio Colao, the CEO of Vodafone Group, compares pilot projects with boats on the sea and framed the associated leadership challenge nicely with the words:

There are big new winds blowing – in data analytics, automation and artificial intelligence – and they will not blow exactly in the same way across all of the organization. In my fleet some boats will gain speed, while others have smaller sails and won’t capture the same momentum. The question is whether you allow each boat to go at its own cruising speed – as we did in the beginning – or if you want to align the fleet and wrap it into a big program, as we are now trying to do. Aligning the boats is helpful for the organization, but you also risk forcing them into a linear speed that ends up being blown away by disruptors [35].

5.5 Empower Management and Employees

Another very crucial aspect of digital transformation regards the continuous empowerment of employees by education and training. This measure cannot be overstated since – simply put – people make change happen [36]. Digital transformation requires technical skills that legacy organizations often lack. Digital pilot projects rely on multidisciplinary and agile innovation teams,16 in which different talents complement each other – diversity is the key to success here [37]. The skills required for a digital product development team (or “squad”17) to be successful range from data science – the skills to turn data into valuable insight and action – to project management, product design, software development, agile methodologies (including design thinking [39], blue ocean strategy [40], and scrum [41]), marketing, and storytelling [42]. An insightful framework for building successful project teams in the digital age is given in, for example, [43].

- 1.

Major internal upskilling programs to activate and retain digital talent

- 2.

External recruiting programs to attract new talent in areas where digital skills and knowledge are rare

- 3.

External collaborations with online talent platforms such as Upwork, Topcoder, and Kaggle, to hire the digital expertise required for the pilot project temporarily

The third option is particularly important since organizations cannot learn everything at once. They rather have to focus and develop their digital core competencies in-house and hire everything else from external sources. This is why it is crucial for organizations to determine and prioritize the data skills they foremost need in advance [45].

Due to the increasing importance of artificial intelligence for its business, the American software company Adobe, for example, recently launched a six-month machine learning training and certification program for its more than 5,000 engineers worldwide. However, the particular skills you need on your digital pilot projects will critically depend on how deeply you plan to get into digital technologies and associated tasks, such as software development and programming. The good news is that many cloud computing vendors and open source platforms offer software tools and online trainings for free – digital technology and knowledge are slowly getting democratized.

Empowering employees is also about developing digital leaders and transforming the role of management. According to Marco Iansiti and Karim Lakhani,

management as supervision, especially of employees performing routine tasks, is finally over. In an AI-powered operating model, managers are designers, shaping, improving and (hopefully) controlling the digital systems that sense customer needs and respond by delivering value. Managers are innovators, as they envision how these digital systems will need to evolve over time. Managers are integrators, as they work to connect disparate digital systems and identify new connections between the firm’s operating model and the customers it serves. And managers are guardians, as they work to preserve the quality, reliability, security, and responsibility of the digital systems they control [29].

Eric Schmidt, Jonathan Rosenberg, and Alan Eagle point out further that

The primary job of each manager is to help people be more effective in their job and to grow and develop. [...] Managers create this environment through support, respect, and trust. Support means giving people the tools, information, training, and coaching they need to succeed. It means continuous effort to develop people’s skills. Great managers help people excel and grow. Respect means understanding people’s unique career goals and being sensitive to their life choices. It means helping people achieve these career goals in a way that’s consistent with the needs of the company. Trust means freeing people to do their jobs and to make decisions. It means knowing people want to do well and believing that they will [46].

5.6 Shape the Organization and Structure

The structure of an organization mirrors the architecture of its products and services [47]. This empirical observation became known as mirroring hypothesis or Conway’s law named after the American computer scientist Melvin Conway, who introduced the idea in 1967 by stating: “Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure” [48]. In other words, interrelated tasks, such as the development of complex products and services, are best performed by cross-functional and highly integrated teams that focus on developing end-to-end customer features rather than a single function or component of the overall product or service only. This is why digital operating models require agile and highly interconnected organizational structures without any isolated silos. Reshaping the organizational structure to establish new ways of collaboration is thus another crucial dimension of digital transformation.

5.6.1 Shape the Organization and Structure: Format Agile Project Teams

Agile innovation teams are small. Jeffrey Bezos famously believes that a team that cannot be fed by two pizzas and thus consists of more than five to ten members inevitably runs into inefficiencies as it requires too much communication and project management, which became known as two-pizza rule [49]. Furthermore, agile project teams rely on interdisciplinarity and are composed of members with varying talents that work in close proximity and encompass all digital and physical skills required to complete the assigned project. They foster ownership and autonomy and follow an explorative approach to innovation that allows them to pivot between different solutions using an emergent strategy – flexible and quick response to change is more important than adherence to plans in the early stage of a digital pilot project. Agile teams usually value creative work environments and less hierarchical bureaucracies and are focused on creating working prototypes rather than excessive documentation. Their approach is centered around the customer, and collaboration is more important than fixed specifications.

- 1.

Decentralized model: Digital initiatives are integrated in all business units and executed more or less independently. Each business unit has its own agile teams and pilot projects.

- 2.

Centralized model: Digital initiatives are orchestrated by a separate entity within the organization that may be headed by a chief digital officer. This center of excellence brings together product managers, data scientists, business analysts, as well as hardware and software developers from different business units and aligns the entire organization around the different pilot projects. One example is the German automotive supplier ZF Friedrichshafen, who set up a centralized analytics lab successfully [50].

- 3.

Excubator model: Digital initiatives run in parallel with an organization’s core business and sometimes even in competition with other business units. A digital excubator18 as a startup-like venture outside the organization leverages digital technologies to create innovative products and services. Its entrepreneurial endeavors provide valuable insights and experience that may serve as a blueprint for future innovations and pilot projects in other divisions of the organization.

Depending on the priorities and particular starting point, many organizations often choose to run hybrid models and implement both a digital center of excellence and an excubator to support their digital agenda.

5.6.2 Shape the Organization and Structure: Establish a Two-Speed IT

Running the different initiatives and pilots of your digital agenda requires an agile IT department and infrastructure that meets the expectations and demands of your agile project teams. This is particularly important since established IT supports usually slow down the innovation cycles of agile projects. But how should an established organization structure its IT department to run a legacy business while supporting digital pilot projects at the same time?

It turns out that the best organizational structure to do this is a two-speed IT, an organizational approach that was proposed by the renowned management consultancy McKinsey & Company in 2014 [51]. A two-speed IT is based on two coexisting IT teams with different focus areas: a (1) slow-speed back end and (2) fast-speed front end. The slow-speed back end or industrial-speed team delivers the IT products and services required to run the legacy business by focusing on mature operations and business processes, such as logistics operations, payment, and banking services. Their services are designed for stability and high-quality data management. The fast-speed front end or digital-speed team, on the other hand, exclusively supports digital pilot projects and provides the resources and support for experimenting with novel digital technologies that are not employed by the legacy business yet as shown in Table 5-2 for better comparison. The industrial-speed team is basically working like traditional IT departments, while the digital-speed team works in an agile manner to enable fast iteration and testing based on customer feedback.

Comparison of the two coexisting IT teams in the two-speed IT operating model

Slow-Speed Back End | Fast-Speed Front End | |

|---|---|---|

Focus | Legacy business – supports and enables mature core operations, such as logistics and production | Pilot projects – supports agile software development and drives experimenting with digital technologies |

Approach | Waterfall approach where software development flows sequentially from conception to testing with separate teams taking over in each phase | Experimental test-and-learn approach based on agile software development methodologies including scrum, rapid prototyping, and design thinking |

Team | Specialized experts with a narrow and clear task – this type of work is generally siloed | Highly interdisciplinary and mixed variety of people with different backgrounds in, for example, business, customer research, software and application development, etc. |

5.7 Establish an Open Innovation Culture

Establishing an agile and open business culture is crucial for completing a digital transformation successfully. In this context, the term business culture refers to the collective capability of an organization to create value by innovation for its customers and employees, which is also why it is sometimes referred to as innovation culture in this particular context. Inspired by the MIT sociologist Edgar Schein – one of the world’s leading scholars in organizational culture – Clayton Christensen defines this integral part of any organization as follows: “Culture is a way of working together toward common goals that have been followed so frequently and so successfully that people don’t even think about trying to do things another way. If a culture has formed, people will autonomously do what they need to do to be successful” [52]. In other words, culture is a unique combination of internal rules and workflows that allow employees to complete certain tasks that recur in their daily work frequently. The more often they solve the task successfully, the more instinctive the workflow becomes. A business culture is thus not created overnight but rather formed through repetition. In order to establish a new business culture successfully, it is consequently not enough to communicate what the culture is. Instead, the management of an organization – as a role model for its employees – needs to adhere to the culture and constantly reinforce it by making decisions and prioritizing projects that are in alignment with it. This is an important point to keep in mind when transforming a traditional and establishing a new innovation culture.

5.7.1 Establish an Open Innovation Culture: Adopt Agile at Scale

While a traditional business culture is best suited for well-established business processes and the exploitation of existing revenue streams, digital innovation cultures are best in exploring new processes and creating new revenue streams based on digital technology. An open innovation culture fosters a much more agile, collaborative, and integrated approach to innovation with a strong customer- and product-centric view. Instead of relying on sequential, inflexible, and often slow product development processes, a digital culture cultivates the emergence of new ideas and empowers employees to deliver results faster by employing a less linear and more iterative approach to product development based on customer feedback. Using agile methodologies across the company – which is sometimes referred to as agile at scale [57] – is thus not a goal in itself but rather a means to an end.

In addition, an open innovation culture motivates employees by giving them freedom and space to explore novel ideas in accord with Frederick Herzberg’s famous motivation theory19 [53]. Eric Schmidt, Jonathan Rosenberg, and Alan Eagle once noted in this context:

You need to [...] go beyond “traditional notion of managing [employees] that focuses on controlling, supervising, evaluating and rewarding/punishing” to create a climate of communication, respect, feedback, and trust. [...] The path to success in a fast-moving, highly competitive, technology-driven business world is to form high-performing teams and give them the resources and freedom to do great things [46] .20

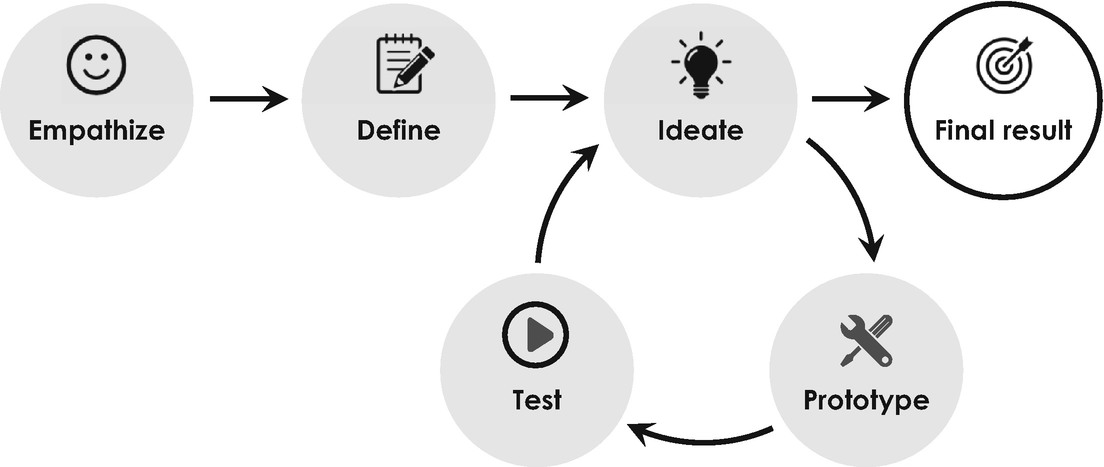

Five steps of the iterative design thinking process (gray circles)

5.7.2 Establish an Open Innovation Culture: Implement Design Thinking

- 1.

Empathize: This first step of the design thinking process is about developing an empathic understanding of the problem from a customer point of view. Typical guiding questions are: What is the customer looking for? What is the customer’s job to be done? What bothers them (most)?

- 2.

Define: Analyzing the observations and synthesizing them into a precise definition of the problem is the main aim of the second step. Are there any unmet needs? What is the problem that should be tackled?

- 3.

Ideate: This is the creative step in the overall process and broadly explores possible solutions to the defined problem independently of whether they appear realistic or unrealistic.

- 4.

Prototype: The design thinking team produces an inexpensive skill down version of the product or service that aims to enhance the customer (or user) experience. This minimum viable product21 (or service) acts as the starting point for the subsequent iterative improvement process.

- 5.

Test: This very last step of the first iteration cycle is about testing the prototype in real-life conditions to examine how it impacts the customer experience. Based on the received customer feedback, successful features are rolled out and optimized, while unsuccessful features are subject to the next iteration cycle beginning with step 4.

Design thinking has successfully been demonstrated to speed up the overall product development process while lowering the cost of failure by experimenting with minimum viable products or services long before their launch. It allows organizations to experiment with prototypes early on in a very inexpensive way by running real-time experiments with their products and services and improving them iteratively based on customer feedback. Furthermore, this agile methodology encourages people to take risks, learn iteratively, and fail fast and early. Design thinking promotes rapid prototyping [55] and continuous learning rather than perfecting a product or service before launching and presenting it to customers.

An open innovation culture built on design thinking and other agile ways of collaboration does not only enable rapid product innovations but also attracts and retains better talent by giving employees more autonomy to implement their own ideas and solutions. Aligning this individual autonomy with the overall digital agenda of an organization is in fact one of the main challenges when transforming the business culture. A good way to reconcile autonomy and alignment is incentivizing right behaviors and discouraging the undesirable ones by stimulating loyalty and commitment to the organization’s overall digital agenda repeatedly. The adoption of human resource processes, such as compensation and promotion systems, that avoid misaligned incentives does usually foster the adherence to a digital agenda too.

5.8 Leverage the Ecosystem

From our previous discussion, we know that the iterative integration of customer feedback into the product or service development process is vital for establishing an open innovation culture focused on the customer – at Amazon, for instance, more than 90% of its innovations are actually triggered by customer feedback. Moreover, engaging with customers systematically is also inevitable for developing personalized products and services that are tailored to meet specific customer needs and expectations. In his 2016 Letter to Shareholders, Jeffrey Bezos noted in this context:

There are many advantages to a customer-centric approach, but here’s the big one: customers are always beautifully, wonderfully dissatisfied, even when they report being happy and business is great. Even when they don’t yet know it, customers want something better, and your desire to delight customers will drive you to invent on their behalf [56].

But customers are not the only stakeholders of your ecosystem that are important to engage with during a digital transformation.

- 1.

Horizontal partnerships between businesses that operate as competitors in the same area are usually used to solve capacity constraints or neutralize risks. Competitors may team up to improve their market position somehow by, for example, pursuing economies of scale, selling their products in more than one market, or cooperating on research and development. One example is Ionity, a Munich-based joint venture formed by BMW, Daimler, Ford, and Volkswagen, for building a high-power charging infrastructure for battery-electric vehicles in Europe.

- 2.

Vertical partnerships refer to collaborations among companies in the same supply chain. A firm might team up with one of its suppliers, for instance, to deepen the relationship, cement long-term commitments, or enable collaboration of the design and distribution of products. An excellent example is Amazon’s marketplace that leveraged vertical partnerships with online sellers to offer more than 88,000 ebooks ready for download from basically day one with the launch of its Kindle store in 2007. With the arrival of digital technologies, vertical partnerships are nowadays also formed between organizations and its end users directly. The American media company Netflix, for instance, utilizes such partnerships to crowdsource innovative ideas for improving its recommendation engine.

- 3.

Cross-industry partnerships are long-term interactions between organizations in different industries. One example is retail banks and telecom companies that team up to offer mobile payment services [58]. Another example is Amazon Web Services that recently started to collaborate with the American online learning platform Udacity to offer different certificate courses and scholarships online [59].

Such partnerships can help you to leverage the full diversity of your ecosystem, create more attention, get valuable feedback from customers, source external ideas, and attract new digital talent. You may also think about collaborating with innovative startup companies or academia for the same reason. Successful digital organizations do also employ a whole range of other initiatives to better position themselves in their particular ecosystem. Such initiatives range from organizing software and hardware development contests or hackathons to visiting researcher programs, summer schools, and conferences and to opening an innovation hub in Silicon Valley or other highly innovative geographic places.

Ultimately, I think that digital transformation provides various opportunities for any organization operating in the private and public sector. The emergence of digital technologies, such as quantum computing, blockchain technology, and artificial intelligence, is framing a mandate for thought leaders to embrace the full potential of digital technology to realign organizations and prepare them for the digital future ahead of us. Digital transformation and its support technologies present valuable and equally unique opportunities for all organizations to differentiate and defend their products and services against the steadily increasing number of competitors.

I hope that the concepts and frameworks presented in this book will inspire new ideas and digital thinking and help you to complete your own digital transformation journey successfully. The best of digital technology is – for sure – still to come.

5.9 Key Points

- Digital transformation regards eight key dimensions:

- 1.

Envisioning a digital business and operating model

- 2.

Selecting an appropriate technology stack and platform

- 3.

Digitizing the business core

- 4.

Identifying scalable pilot projects

- 5.

Empowering employees

- 6.

Shaping the company structure and organization

- 7.

Establishing an open innovation culture

- 8.

Leveraging the ecosystem and engaging with customers

The most successful business models integrate around the customers’ job to be done and aim for doing this job better and better over time by leveraging sustaining and/or disruptive innovations and associated technologies. Customer journeys can help in this context to tailor a product or service to the specific customers’ needs.

The selection of an appropriate technology stack that supports the digital business and operating model best typically involves choosing a cloud computing vendor. The most popular vendors are Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud. Their services generally fall into four main categories, namely, (1) infrastructure-, (2) platform-, (3) software-, and (4) business-process-as-a-service depending on the client’s level of involvement.

Digitizing the core of a business or organization by leveraging a technology stack is about creating an appropriate IT infrastructure that supports internal processes. In the case of established organizations, this process typically involves the gathering, cleaning, normalization, and integration of data scattered in silos into an integrated data platform that allows for sharing and analyzing big data across the organization easily.

Successful pilot projects are built around a concrete (business) problem or purpose. They are scalable and aim for quick wins to create enthusiasm for digital transformation in the organization.

Empowering employees by education and training involves building up multidisciplinary skills ranging from agile methodologies to digital marketing and programming skills. The different initiatives aim for creating a digital mindset that allows for evaluating and anticipating the impact of digital technology on organizations and society.

Rethinking and shaping the organizational structure is particularly important since companies cannot disrupt itself. The excubator model and a two-speed IT have thus been proven to be particularly successful in running digital pilot projects.

Establishing an open innovation culture with a strong customer- and product-centric view is at the heart of any digital transformation. Design thinking may help to develop new products and services centered around the customers’ job to be done purposefully.

Leveraging an organization’s ecosystem to engage with customers will is crucial for optimizing products and services iteratively. Collaborations and partnerships with other players in the ecosystem may help to attract new talent and grow the digital business rapidly.

5.10 Further Reading

Nadella, S. et al.: Hit Refresh: The Quest to Rediscover Microsoft’s Soul and Imagine a Better Future for Everyone. Harper Business (2017).

Frankenberger, K. et al.: The Digital Transformer’s Dilemma: How to Energize Your Core Business While Building Disruptive Products and Services. Wiley (2020).

Weill, P. and Woerner, S. L.: What’s Your Digital Business Model? Six Questions to Help You Build the Next-Generation Enterprise. Harvard Business Review Press (2018) – a free webinar that covers various aspects of this book is available online on https://hbr.org/webinar/2018/03/building-your-digital-business-model/.

Orban, S. et al.: Ahead in the Cloud: Best Practices for Navigating the Future of Enterprise IT. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (2018).

Reeves, M. et al.: Your Strategy Needs a Strategy: How to Choose and Execute the Right Approach. Harvard Business Review Press (2015).22

Ries, E.: The Lean Startup: How Today’s Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create Radically Successful Businesses. Currency (2017).

Brown, T.: Change by Design: How Design Thinking Transforms Organizations and Inspires Innovation. HarperCollins (2009).

5.11 References

- 1.

Nadella, S.: Satya Nadella email to employees on first day as CEO. Microsoft (2014). https://news.microsoft.com/2014/02/04/satya-nadella-email-to-employees-on-first-day-as-ceo/

- 2.

Condon, S.: Google I/O: From “AI first” to AI working for everyone. ZDnet.com (2019). www.zdnet.com/article/google-io-from-ai-frist-to-ai-working-for-everyone/

- 3.

- 4.

Nadella, S.: Embracing our future: Intelligent Cloud and Intelligent Edge. Microsoft (2018). https://news.microsoft.com/2018/03/29/satya-nadella-email-to-employees-embracing-our-future-intelligent-cloud-and-intelligent

- 5.

Ranger, S.: Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella: The whole world is now a computer. ZDNet (2018). www.zdnet.com/article/microsoft-ceo-nadella-the-whole-world-is-now-a-computer/

- 6.

Green, D.: Jeff Bezos has said that Amazon has had failures worth billions of dollars – here are some of the biggest ones. Business Insider (2019). www.businessinsider.com/amazon-products-services-failed-discontinued-2019-3/

- 7.

- 8.

Weill, P. and Woerner, S. L.: Is Your Company Ready for a Digital Future? MIT Sloan Management Review (2017). https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/is-your-company-ready-for-a-digital-future/

- 9.

Colson, E.: What AI-Driven Decision Making Looks Like. Harvard Business Review (2019). https://hbr.org/2019/07/what-ai-driven-decision-making-looks-like/

- 10.

Chandler, A. D. and Hikino, T.: Scale and Scope: The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism. Harvard University Press. Cambridge, Massachusetts (1990).

- 11.

Richardson, A.: Using Customer Journey Maps to Improve Customer Experience. Harvard Business Review (2010). https://hbr.org/2010/11/using-customer-journey-maps-to/

- 12.

Edelman, D. C. and Singer, M.: Competing on Customer Journeys. Harvard Business Review (2015). https://hbr.org/2015/11/competing-on-customer-journeys/

- 13.

Weill, P. and Woerner, S.: What’s Your Digital Business Model? Six Questions to Help You Build the Next-Generation Enterprise. Harvard Business Review Press (2018). Please also see https://cisr.mit.edu/publication/2013_0401_DigitalEcosystems_WeillWoerner/

- 14.

Christensen, C. M. et al: Know Your Customers’ “Jobs to Be Done.” Harvard Business Review (2016). https://hbr.org/2016/09/know-your-customers-jobs-to-be-done/

- 15.

Christensen, C. M. et al.: What Is Disruptive Innovation? Harvard Business Review (2015). https://hbr.org/2015/12/what-is-disruptive-innovation/

- 16.

Christensen, C. M. et al.: How Will You Measure Your Life? HarperCollins Publishers (2012).

- 17.

McGrath, R. G. and MacMillan, I.: Discovery-Driven Planning. Harvard Business Review (1995). https://hbr.org/1995/07/discovery-driven-planning/

- 18.

Rogers, B.: Virtualization’s Past Helps Explain Its Current Importance. IBM Systems Media (2017). https://ibmsystemsmag.com/IBM-Z/02/2017/virtualization-past-current/

- 19.

Mell, P. and Grance, T.: The NIST Definition of Cloud Computing. NIST (2011). https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/details/sp/800-145/final/

- 20.

Amazon Web Services (2006). https://aws.amazon.com/de/about-aws/whats-new/2006/07/11/amazon-simple-storage-service-amazon-s3 and https://aws.amazon.com/de/about-aws/whats-new/2006/08/24/announcing-amazon-elastic-compute-cloud-amazon-ec2-beta/

- 21.

McDonald, P.: Introducing Google App Engine + our new blog. Google (2008). https://googleappengine.blogspot.com/2008/04/introducing-google-app-engine-our-new.html/

- 22.

Microsoft Cloud Services Vision Becomes Reality With Launch of Windows Azure Platform. Microsoft (2009). https://news.microsoft.com/2009/11/17/microsoft-cloud-services-vision-becomes-reality-with-launch-of-windows-azure-platform/

- 23.

IBM to Acquire SoftLayer to Accelerate Adoption of Cloud Computing in the Enterprise. IBM (2013). www-03.ibm.com/press/us/en/pressrelease/41191.wss/

- 24.

Moore, G. A.: Dealing with Darwin: How Great Companies Innovate at Every Phase of Their Evolution. Penguin Books (2005).

- 25.

Bock, R. et al.: What the Companies on the Right Side of the Digital Business Divide Have in Common. Harvard Business Review (2017). https://hbr.org/2017/01/what-the-companies-on-the-right-side-of-the-digital-business-divide-have-in-common/

- 26.

Kennon, J.: Bloomberg Terminal: The Standard for Professional Investors and Financial Institutions. the balance (2019). www.thebalance.com/what-is-a-bloomberg-terminal-or-bloomberg-machine-358002/

- 27.

Clarke, R.: Information Wants to be Free. Xamax Consultancy (2000). www.rogerclarke.com/II/IWtbF.html

- 28.

Earley, S. and Bernoff, J.: Is Your Data Infrastructure Ready for AI? Harvard Business Review (2020). https://hbr.org/2020/04/is-your-data-infrastructure-ready-for-ai/

- 29.

Iansiti, M. and Lakhani, K.: Competing in the Age of AI: Strategy and Leadership When Algorithms and Networks Run the World. Harvard Business Review Press (2020).

- 30.

Rotman, D.: AI is reinventing the way we invent. MIT Technology Review (2019). www.technologyreview.com/2019/02/15/137023/ai-is-reinventing-the-way-we-invent/

- 31.

Iansiti, M. and Lakhani, K. R.: Competing in the Age of AI. Harvard Business Review (2020). https://hbr.org/2020/01/competing-in-the-age-of-ai/

- 32.

Porter, M.: What is Strategy? Harvard Business Review (1996). https://hbr.org/1996/11/what-is-strategy/

- 33.

Ng, A.: How to Choose Your First AI Project. Harvard Business Review (2019). www.hbr.org/2019/02/how-to-choose-your-first-ai-project/

- 34.

Sutcliff, M. et al.: The Two Big Reasons That Digital Transformations Fail. Harvard Business Review (2019). https://hbr.org/2019/10/the-two-big-reasons-that-digital-transformations-fail/

- 35.

Kerr, W. R. and Moloney, E.: Vodafone: Managing Advanced Technologies and Artificial Intelligence. Harvard Business School (2018). www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=54141/

- 36.

Frankiewicz, B. and Chamorro-Premuzic, T.: Digital Transformation Is About Talent, Not Technology. Harvard Business Review (2020). https://hbr.org/2020/05/digital-transformation-is-about-talent-not-technology/

- 37.

Rock, D. and Grant, H.: Why Diverse Teams Are Smarter. Harvard Business Review (2016). https://hbr.org/2016/11/why-diverse-teams-are-smarter/

- 38.

Takeuchi, H. and Nonaka, I.: The New New Product Development Game. Harvard Business Review (1986). https://hbr.org/1986/01/the-new-new-product-development-game/

- 39.

Brown, T.: Design Thinking. Harvard Business Review (2008). https://hbr.org/2008/06/design-thinking/

- 40.

Kim, W. C. and Mauborgne, R.: Blue Ocean Strategy. Harvard Business Review (2004). https://hbr.org/2004/10/blue-ocean-strategy/

- 41.

Rigby, D. K. et al.: Embracing Agile. Harvard Business Review (2016). https://hbr.org/2016/05/embracing-agile/

- 42.

Nussbaumer Knaflic, C.: Storytelling with Data. John Wiley & Sons Inc., New Jersey (2015).

- 43.

Berinato, S.: Data Science and the Art of Persuasion. Harvard Business Review (2019). https://hbr.org/2019/01/data-science-and-the-art-of-persuasion/

- 44.

Schmidt, E. and Rosenberg, J.: How Google Works. Grand Central Publishing (2015).

- 45.

Littlewood, C.: Prioritize Which Data Skills Your Company Needs with This 2ÃŮ2 Matrix. Harvard Business Review (2018). https://hbr.org/2018/10/prioritize-which-data-skills-your-company-needs-with-this-2x2-matrix/

- 46.

Schmidt, E. et al.: Trillion Dollar Coach: The Leadership Playbook of Silicon Valley’s Bill Campbell. HarperCollins (2019).

- 47.

Colfer, L. and Baldwin, C. Y.: The Mirroring Hypothesis: Theory, Evidence and Exceptions. Industrial and Corporate Change 25 (5), 709–738 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtw027

- 48.

Conway, M. E.: How do committees invent? Datamation 14 (5), 28–31 (1968).

- 49.

Anthony, S. D.: Five Ways to Innovate Faster. Harvard Business Review (2013). https://hbr.org/2013/07/how-to-innovate-faster/

- 50.

Goby, N. et al.: How a German Manufacturing Company Set Up Its Analytics Lab. Harvard Business Review (2018). https://hbr.org/2018/11/how-a-german-manufacturing-company-set-up-its-analytics-lab/

- 51.

Bossert, O. et al.: A two-speed IT architecture for the digital enterprise. McKinsey & Company (2014). www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/a-two-speed-it-architecture-for-the-digital-enterprise/

- 52.

Christensen, C., Allworth, J., and Dillon, K.: How Will You Measure Your Life. HarperCollins Publishers (2012).

- 53.

Herzberg, F.: One More Time: How Do You Motivate Employees? Harvard Business Review (2003). https://hbr.org/2003/01/one-more-time-how-do-you-motivate-employees/

- 54.

Duhigg, C.: What Google Learned From Its Quest to Build the Perfect Team. The New York Times Magazine (2016). www.nytimes.com/2016/02/28/magazine/what-google-learned-from-its-quest-to-build-the-perfect-team.html/

- 55.

Martin, R. L.: The Unexpected Benefits of Rapid Prototyping. Harvard Business Review (2014). https://hbr.org/2014/02/intervention-design-building-the-business-partners-confidence/

- 56.

- 57.

Relihan, T.: Agile at scale, explained. MIT Management Sloan School (2018). https://mitsloan.mit.edu/ideas-made-to-matter/agile-scale-explained/

- 58.

Taga, K. et al.: Convergence of banking and telecoms. Arthur D. Little (2015). www.adlittle.com/sites/default/files/viewpoints/ADL_ConvergenceOfBankingAndTelecoms.pdf/

- 59.