Prelude

Digital Modelling for Urban Design

View of the north central axis of Beijing with the Olympic Village in the foreground. Prepared by the Beijing Organizing Committee for the Games of the XXIX Olympiad and the Beijing Institute for Urban Planning.

With all the comforts of a shopping mall, escalators glide visitors up to the top floor of the Beijing Planning Exhibition Hall along a huge, wall-hung cast bronze model of Old Beijing. The Ming Dynasty Imperial City was substantially intact in the model shown, which depicts the city in 1949, the year the People's Republic of China was founded. On the third floor of the museum you can walk over a giant bottom-lit satellite photograph of the present-day city - as if you could pass through your computer screen and walk on the surface of Google Earth. Physical models represent the city's Master Plan for the Olympic City south to the Forbidden City and east to the Central Business District and Chaoyang Park. The model gives visitors a taste of the modern architectural and urban design spectacle that Beijing has broadcast to the world for the 2008 Olympics. Arriving at the top floor, visitors are ushered into a small theatre, where they are given special 3-D vision glasses and strap themselves into moving seats. The lights dim and the audience begins a simulation fly-through of the city of the future. Moving seats sway during the computer-generated animation above an ascendant future Beijing, reclaiming its position as the centre of the world.

The latest in digital imaging and 3-D modelling technology is likewise on display for anyone browsing the fundraising website of the National September 11 Memorial and Museum.1 Sunlight dapples through a forest canopy. The oak leaves in the foreground dissolve to reveal the corner of a two-tiered square waterfall cascading first into a reflecting pool before disappearing below the ground. The camera tilts down then dissolves into an aerial view of the site, a forest grove with two giant pools of water. It spins around before focusing on a tracking close-up at ground level which points towards a glass building through the forest grove. Another dissolve, and the virtual camera ascends from within the glass pavilion while looking down along two tall structural columns from Minoru Yamasaki's destroyed towers. The camera flips its perspective and now spins, looking up the remnant artefacts. Two structural columns - elements from Yamasaki's destroyed towers - can be seen through the glass walls of the Museum entry pavilion. Another dissolve and suddenly it is September again and the trees have turned shades of russet, orange and yellow. The camera glides along the tree tops in the plaza scored with grassy strips. Another dissolve, the trees are green again as we zoom out and up away from one of the signature reflecting pools.

National September 11 Museum Pavilion exterior with salvaged World Trade Center tridents. Image created by Squared Design Lab, provided by National September 11 Memorial & Museum.

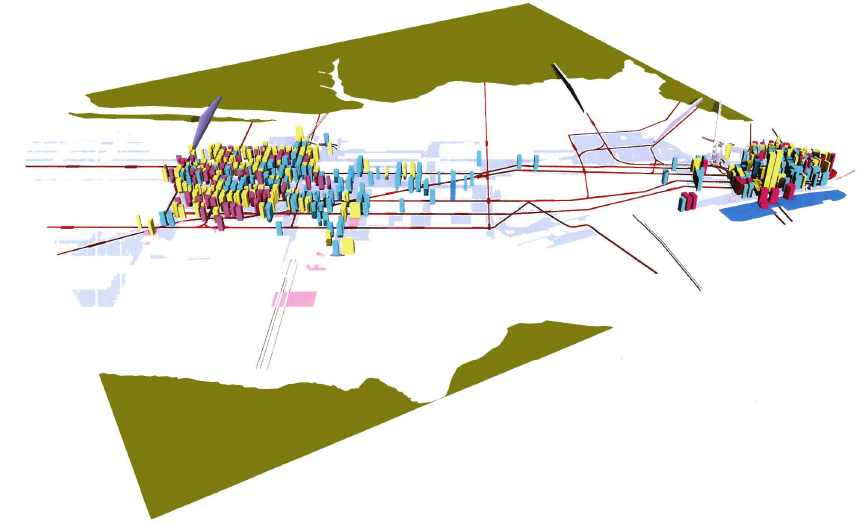

Spectacular digitally animated fly-throughs tied to websites or physical experiences are the common currency of 21st-century globalisation and urbanisation. Any development from Dubai to São Paulo requires the virtual magic-carpet ride - one that never quite rests or touches ground in the city. Instead of communicating the city as the site of contest and struggles for social justice and difference, urban design and its projective representations is currently a regime of high-cost, fast-moving, complex opaque simulations of a glittery, seamless modern world. It seems that no physical design project can exist without a complementary digital representation, instructing people on how to experience it. Meanwhile, these spectacular representations mask the dirty digital sweatshop work of urban design practice. Digital designers must contend with layers and layers of existing geotechnical, utility, infrastructural and legal information as well as files from environmental, engineering, parking, structural, mechanical, marketing, landscape and architectural consultants. All these layers of spatial data are compiled on Computer Aided Design (CAD) and Geographic Information System (GIS) files which, when superimposed, look as confusing and complex as Heinrich Schliemann's successive layers of ancient Troy.

Digital Modelling for Urban Design unmasks the spectacular surfaces of virtual reality to redirect the power of computer-generated modelling towards exploring the environmental, social and psychological complexity of urban design practice today. This book advocates a more complex, interactive, reiterative and collaborative urban informational feedback system for urban design practice aided by the use of digital technologies. The techniques introduced in this book reclaim urban design as a collective and contested enterprise, where the city is continually remade by a diverse array of urban actors and agents. Cities are dynamic assemblages of psycho-socio-natural patches and polyvocal cultural arenas. Urban design information and communication is being claimed by an increasingly diverse array of urban actors, while current modes of professional representation, both spectacular and bureaucratic, remain overly opaque and authoritative. YouTube, Google Earth, 3D Warehouse and SketchUp, utilising inferior production values than the professional simulators, engage countless digital modellers and video makers in the task of discussing and representing the world's villages, neighbourhoods, institutions, public spaces and cities. This claim on urban design practice through new popular modes of digital communication is not just the creation of public forms of information, mediation and representation, but a mobilisation of a new reflexive, responsive and resilient urban public sphere itself.

This book develops its argument through examples drawn from the rich urban design contexts of Rome, New York and Bangkok. In modelling Rome I analyse Rodolfo Lanciani and Giovanni Battista Piranesi's critical representations of the city as an arena for multiple narratives rather than a uniform representation of political authority. In modelling New York, I examine the changing role of urban design in the face of the dispersion of power among the multiple actors who form the bureaucratic capitalist city. In modelling Bangkok, I focus is on the role of popular media and consumer culture in shaping both urban space and the contemporary imagination in an era of globalisation. Through these examples I argue that shifts, disruptions and disjunctions between the agents producing and exerting forces to shape the city - whether over centuries in Rome, decades in New York, or in the rapid cycles of fashion in Bangkok - create rich, intricate and diverse urban forms. Digital modelling can assist in the collective engagement of a much more diverse range of actors and agents in the production of urban design experiments within circuited feedback loops is essential in confronting the pressing social and environmental issues we all face today.

Flattening Urban Design

Digital Modelling for Urban Design is directed to a wide audience of students, architects, designers, planners and citizen designers - anyone wishing to be involved in the complex decision-making processes in shaping the urban environment. This book, therefore, develops the use of digital technologies as a tool of public advocacy and the creation of collective forms of urban knowledge. Digital modelling can expand urban design practice to an informational and communication as well as a representational system. The aspects of digital modelling promoted, therefore, are not the technical aspects of software, programming or scripting, but rather the broad and accessible array of popular digital technologies. Thomas L Friedman celebrates events such as the widespread use of personal computers, the introduction of web browsers, workflow software, open-sourcing, outsourcing, offshoring, supply chaining, insourcing, informing, and a new generation of digital, mobile, personal and virtual technologies. Open-source and interconnected digital technology ‘flattens the playing field’ and offers the opportunity for a much wider array of actors to engage in the challenges and benefits of globalisation and urbanisation.2

More radically, hacker digital culture promotes ‘mash-ups’ - ‘recombinant methods in the various forms of combining, sampling, pangender performance, bricolage, detournement, ready-mades, appropriation, plagiarism, theater of everyday life, constellation, and so on … an ongoing task for those who hope to see the decline of authoritarian culture’.3 The digital circulation of information, images and ideas about and for the city constitutes a virtual public realm which can continually produce new urban design models for rethinking, recreating and re-inhabiting the physical environment of cities. Feedback loops are tightened in such a networked context, enhancing the reflective and reflexive in addition to the productive aspects of design. Popular forms of digital modelling have the potential to widen access to power and knowledge in order to activate rather than pacify the public who constitute the primary audience for these new forms of representational production.

Modelling Discourse

If we are to consider digital tools in such broad terms, we must also expand our notion of urban design modelling as an activity which can assist in filtering some of the noise which the word ‘feedback’ also implies. Designers, scientists and policy makers all construct urban models but the definition of ‘modelling’ differs sharply between disciplines. Designers use the term to refer to a 3-D miniature, this year's new car, a person who shows off new clothes. A scientist's model is a quantitative demonstration of a theory of how something functions. For policy makers a model is a picture of how the environment ought to be made, a proscription of a ‘good’ form or a ‘fair’ process which is a prototype to follow. According to Kevin Lynch, the visualisation of urban design through models creates a mental structure, a collective philosophical and psychological image shared by city inhabitants. Lynch's primary concern is for ‘good urban form’ and urban design models, as public policy is of primary importance for him. Design decisions should be based on ‘models’ collectively understood and on normative values of good and bad.’4

Lynch uses the Baroque city's axial network as an example of a ‘good’ urban design model: symbolic landmarks are located at commanding points in the terrain, connected by major streets with controlled unified facades or bordering landscapes. Strong visual effects form the groundwork for public symbolism and create a memorable general structure without imposing control on every part and without requiring an unattainable level of capital investment. The Baroque city achieves sensibility within an economy of means.5 But the Baroque city is also a strategy for the application of centralised power in urban space. Lynch himself argues that Baroque's ideal order dominates nature, masks difference and is inflexible to dynamic change.6 The Master Plan as an urban design practice will be traced to Baroque Rome beginning in Chapter 2.

Radial street network of Baroque Rome situated between the medieval city at the bend of the Tiber River and the scattered Christian basilicas built over the ruins of the ancient city. Layered ink drawing on Mylar from Transparent Cities. 1994.

Lynch also finds deficiencies in the stock of the urban models of his time: little is said about workplace, marginal spaces, wastelands, fringe areas, transition spaces, vacant lands, dead storage areas and underutilised places. Street traffic is prioritised, but flows, conservation and management of material and energy sources or information cannot easily be dealt with. Sensory models are not openly specified.7 Baroque, Enlightenment and Modernist urban design models refer only to a completed form, giving no account of the process by which the form is achieved, and ignoring the reality of continuous change. They exclude media, mobility, migration, adaptation, temporary uses and transitional as well as emergent forms of social life. For Lynch, a useful model is one where the situation is stated, performance is specified and reasoning laid bare, fully open to political correction.8 In Chapter 4, a genealogy of New York's central business districts will be traced in order to understand the emergence of urban design as a method of political correction which utilises zoning to shape real estate development.

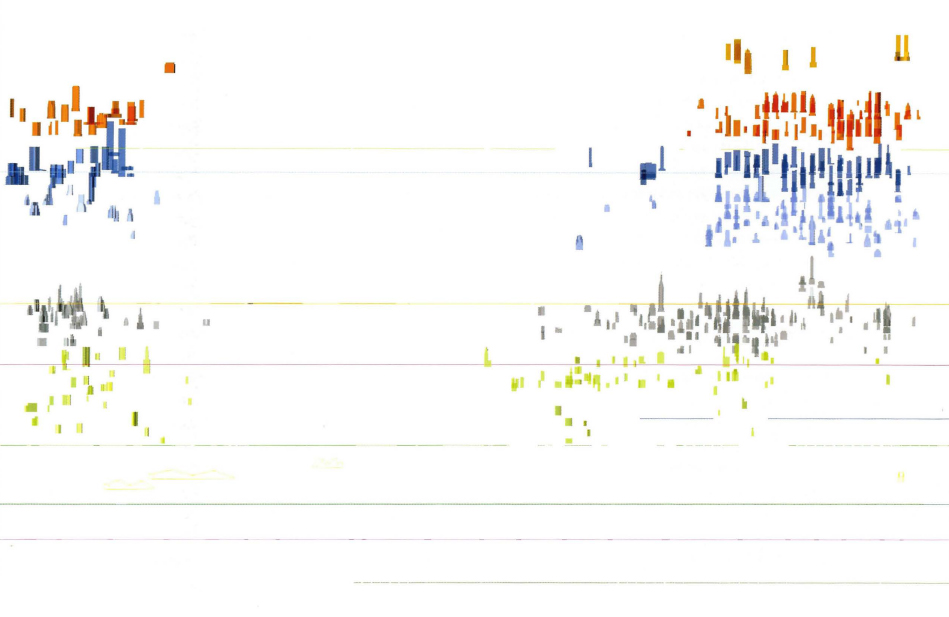

Digital model of Transparent Cities showing the concentration of high-rise office building in Lower and Midtown Manhattan overlaid with zoning districts and subway lines, 1996.

Lynch's vantage point was contained within the late-20th-century American bureaucratisation of urban design practice where computers were just beginning to have an impact on design processes.9 Twenty-five years later, his critique is even more evident with the emergent potential and flattened world of new digital technologies. Globalisation and digitisation have greatly increased the need for dynamic, transparent, continually changing urban design models, yet modelling remains in the hands of specialist designers, scientists and policy makers. This book broadens the historical and geographical context of urban design modelling to give an expanded view of modelling for urban design. Instead of outlining normative models of how a city ought to be made by specialists, this book promotes the open-ended possibilities of a digital world of wikis, blogs, online social networks, Facebook, MySpace, Flickr, and free 3-D modelling software such as SketchUp, which are assisting the dissemination of information and technologies for re-imagining as well as remaking the global city and our place in it. The future of urban design in a context of ‘lifestyle’ and consumer preferences will be explored in the central shopping district of Bangkok in Chapter 6.

Detail of digital model of Bangkok's central shopping district showing the concentration of new and refurbished mails connected to the elevated Skytrain, Chulalongkorn University Faculty of Architecture. 2007.

Development of the Book

Digital Modelling for Urban Design is based on over two decades of research, practice and teaching in architecture and urban design, but also draws from living and working in the three cities which comprise the examples in this book. Analytical discussions of Rome, New York and Bangkok situate historical speculation and abstract knowledge with reflections on empirical experience and real world measurement. This book, therefore, is both theoretical and practical, interspersing critical discussions linked to the writings of Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari, Aldo Rossi, Grahame Shane, Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi, with intimate knowledge of the three cities I know best. The examples, therefore, are grounded in my own bodily experience of everyday life in these three cities over time.

Living in Rome and New York between 1985 and 1995, I created an archaeology of urban design models by developing a comparative archive of historical information on both cities.10 In New York and Bangkok between 1995 and 2005, I developed a genealogy of the transition of urban design from a bureaucratic to a marketing discipline by comparing the development of Manhattan's business districts and Bangkok's shopping centres over time. Manhattan Timeformatlons11 is a genealogical digital model that has captured a wide international audience since it was first broadcast on a website in 2000, marking a moment of great optimism about globalisation, digital technologies and urban design. Living in both New York and Bangkok, I have been able to track the ideological and economic dynamics of globalisation, from opposite points on the planet. The digital model I developed with faculty and students at Chulalongkorn University over this time constitutes a schizoanalysis of four decades of the development of Bangkok's central shopping district, and comprises the last case study for the book.12

Arjun Appadurai has pointed out that the initial promise of globalisation to create new resources for human imagination and social practices through the twin forces of media and migration also produced new forms of hatred, ethnocide and ideocide.13 It is, however, in Appadurai's spirit of ‘grassroots globalisation’: the worldwide effort of activist non-governmental organisations and movements to seize and shape the global agenda on such matters as human rights, gender, poverty, environment and disease, and to seek ways to make globalisation work for those who need it most and enjoy it least - the poor, the dispossessed, the weak, and the marginal populations of our world. The conclusion, written following two recent residencies in India and China as a research fellow with the New School's India China Institute, attempts to direct the lessons from these two decades of research in Rome, New York and Bangkok towards the urban future of India and China.14

Urban design, therefore, is presented here within transhistorical, transcultural and transdisciplinary contexts in order to position digital modelling as the act of creating moving, interactive, four-dimensional communication systems situated within the histories of theory, design and representation. Certainly such an expansion of the representational and informational capacities of digital modelling will result in even more spectacular urban design simulations from contact with a wider range of source material and constituencies. Two clear departures from contemporary practice - questioning who makes the city and who makes the images of the city - both call for a new public realm constituted by open and transparent forms of design and representation. The spectacle of urban design and representation can be one in which a broad array of actors advocate and participate in the making of both the city and its images rather than constituting an audience passively consuming urban simulations constructed by specialists.

Organisation of the Book

The introductory chapter of Digital Modelling for Urban Design presents a close analysis of the way digital modelling participated in the public debate around the redesign of Ground Zero in New York. The Innovative Design Study for rebuilding Lower Manhattan's World Trade Center was a mass media event that revealed many dilemmas and opportunities for urban design when it is spectacularised through digital modelling and communication technologies. Following the Introduction, the book is structured around three pairs of chapters which each present a methodological approach to digital modelling for urban design, coupled with a particular case study. Part I introduces archaeological modelling for urban design followed by a digital analysis of the Roman Forum. Part II presents genealogical modelling for urban design through the example of Manhattan's skyscraper business districts’ formation over time. Finally, Part III concludes with a discussion of schizoanalytical modelling for urban design, followed by an analysis of the experience of Bangkok's central shopping district. These three sections outline a critical framework in order to question the society of the spectacle within which digital simulation for urban design is currently trapped.15 This is not an argument against the long relationship between city life and spectacle - in fact, Rome, New York and Bangkok are among the world's most spectacular cities. Rather, it highlights the passivity of the society of the spectacle as only consumers rather than producers of urban design representations.

The three book sections comparatively model archaeological archives, genealogical timelines and schizoanalytical diagrams. Archaeological Modelling for Urban Design will lead to a discussion of historically situated urban embeddedness. Political, ecological and social patterns of an urban site will be examined as processes operating at various scales nested and layered within the specific terrain and events of an urban site. Genealogical Modelling for Urban Design will question singular urban subjectivity and authorship through a process of unlocking the genetic code and links between social practices, institutions and forms over time. The study of urban morphogenesis examines the evolutionary recombination of forces which create urban form.16 Finally, Schizoanalytical Modelling for Urban Design will question urban representation and identity as a singular truth in a globalising world of multiple disjunctive flows. Mediated images experienced by a mobile society suggest that the ‘reality’ or ‘truth’ of a particular locality must be continually interrogated and re-imagined through circuits of attention, memory and reflection. Digital modelling will examine the construction of recombinant urban identities as well as urban designs, where momentary constellations of fragments join to create space, events and shifting life worlds.

Archaeology and War

Chapter 1 begins with an archaeology of urban design in the sense the word is used by Michel Foucault,17 exposing urban design as a discipline continually re-imagined within the ruptures in historical formations of knowledge. Urban design in Rome, New York and Bangkok will be compared through changing social discourse, visual representations and urban artefacts. Archaeological Modelling for Urban Design compares layered digital models of all three cities across time. Urban design modelling and representations are historical discourses and disciplines that will be situated through the comparison of the transformation of urban design practice as it moves through different places, cultures, as well as through political and economic systems. Comparative digital modelling reveals the particular ruptures in the formation of urban strata due to new paradigms, discourse and forms of representations.

Archaeological modelling unpacks urban embeddedness in three ways:

(1) Unbounding an urban site: an urban boundary establishes a closed set of relations within and outside the limits of a site. All sites are framed by physical enclosures, legal restrictions, political boundaries and property relations. We directly experience the world in small fragments and assume the accuracy of the representations of that which lies outside our field of action. Archaeology therefore is a critical act by the designer in unbounding an urban site by establishing new sets of relationships beyond normative conceptions and perceptions of site limits.

(2) Delayering: urban complexity is unpacked through a process of modelling various attributes and elements of the city as separate layers of information. This process enables the isolation and investigation of the relationships between urban elements and perceptions, as well as data from various disciplines - environmental, social, economic, etc. While Geographic Information System (GIS) ties urban mapping to data sets, delayering urban models is a three-dimensional operation of uncovering the disruptive practices in various strata of urban sites as materially constructed over time.

(3) Rescaling: techniques are introduced to move between various scales and levels of organisation in the design process. Digital modelling programs allow the designer to zoom in and out in order to engage work at several scales simultaneously: global economic and migration patterns, regional landscapes and infrastructures, district enclaves of blocks and streets, local pockets of lived spaces, and the scalelessness of the imagination.

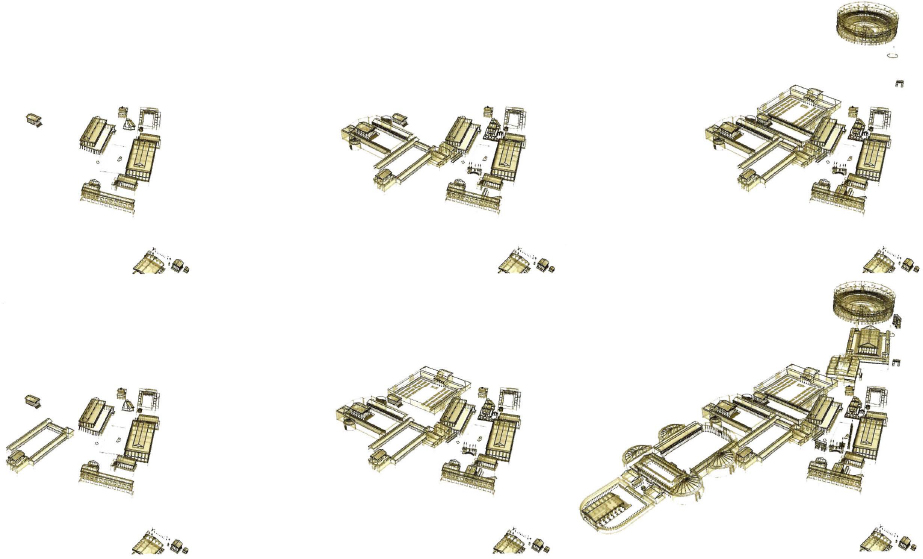

Chapter 2, War, traces some of the earliest models of urban design practice and representation, focusing on how the Roman Forum was developed to display the spoils of war. Following Aldo Rossi,18 the chapter begins with a detailed discussion of a singular urban artefact - the Roman Forum - its development over time, and how it is understood and mediated as an urban artefact through various forms of representation and experience.

This chapter examines the science of archaeology itself as a politicised urban design act, often partnered with acts of territorial aggression. Archaeology shaped the city's relation to historical knowledge, becoming an instrument of legitimising authority and power through association with Imperial Rome. The Forum, before archaeologists carved this massive void in the centre of the city, was for centuries a peaceful cow pasture on top of what became a municipal dump, after garbage collection ended with the termination of Imperial order and services. Renaissance cardinals, popes and architects essentially regenerated a ‘brownfield’ when one of the world's first botanical gardens and an urban ‘allée’ of trees were planted above and on the Forum, which today is a huge void in the centre of the city.

Genealogy and Trade

Chapter 3 turns to modelling the development of urban design as a bureaucratic discipline which develops codes and rules for shaping, hybridising and transforming urban space over time. Genealogical Modelling for Urban Design will diagram timelines of churches in Rome, skyscrapers in New York and shopping centres in Bangkok to understand how social actors transform neighbourhoods, institutions and public space over time. Grahame Shane's Recombinant Urbanism provides an urban design theory to assist in understanding the genealogy of urban design as hybridisation of urban enclaves, armatures and heterotopias.19 Genealogical modelling can trace both the descent of top-down urban authority and legitimacy and the emergence of bottom-up forms of urban life. Genealogy is based on the premise that historical institutions and other features of social organisation evolve not smoothly and uniformly, gradually developing their potential through time, but discontinuously, and must be understood in terms of difference rather than continuity. New social formations appropriate and abruptly reconfigure older institutions or revive various features of extant urban models by selectively recombining them to suit their own purposes.20

Archaeological layered model of Rome showing the growth of the Forum over time, 2008.

In order to explore genealogical modelling, the uniformity and singularity of urban simulation can be countered in three ways:

(1) Repositioning points of view: the standard fly-through or walk-through view is replaced by the deployment of multiple vantage points of urban data. Toggling between layered plans, multiple elevations, axonometrics and perspectives repositions the designer within and without the designed site from various points of view. This process considers modes of representation which can accommodate and engage various positions and interpretations rather than uniform narratives.

(2) Giving time a dimension: timelines allow for the analysis of ‘family trees’ of genetic descent or the creation of emergent forms through cross-fertilisation and hybridisation. The creative and destructive forces of various urban actors and agents can be traced and cross-referenced in time and space. Formal patterns and social behaviour can be diagrammed as swarms, clusters or absences in space and time.

(3) Polyvocalities: computer networking eases the integration of collaborative work. Designers work individually on local probes of larger-scale urban assemblages, which are derived through group affinities, rather than the Master Plan or a single vision. The cut and paste abilities of computer software allow for individual projects to be layered and juxtaposed, easing the collaborative process. Group identity is also questioned since affinities are partial and limited. Also interdisciplinary collaborations can be created by importing spatialised data from planning, preservation, real estate and the social sciences.

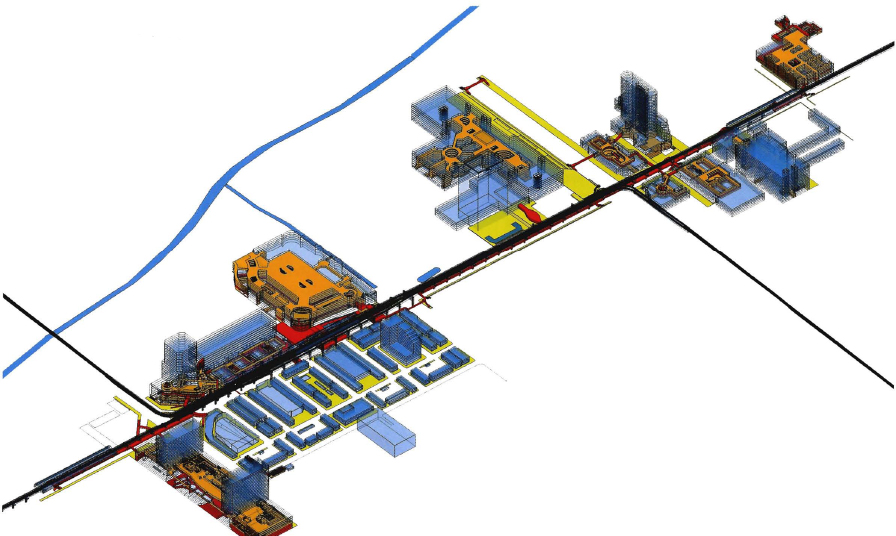

Chapter 4, Trade, describes how urban design developed the abstract coding of the city through establishing specialised business enclaves controlled through zoning incentives during the 20th century in New York - a city based on trade and finance. An online digitally modelled timeline of the development of high-rise office districts in Manhattan is presented as a genealogy of urban design in the context of the 20th-century capitalist city. Urban design was institutionalised as a modern discipline in New York after the Second World War, and the form of the city became altered by zoning codes and the creation of special districts and development incentives in concert with the changing shape of financial capitalism itself. While an archaeological approach literally digs deep down into a specific site in order to uncover the successive layers of historical strata, a genealogy, like tracing a family tree, moves in tangential lines both backward and forward in order to understand the interrelation between genetic legacy and specific features of current and future development.

Schizoanalysis and Desire

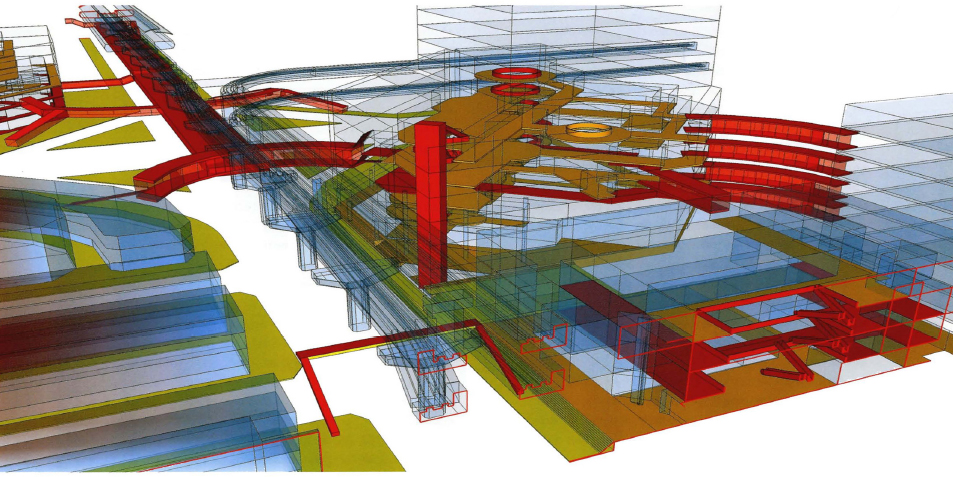

Chapter 5 utilises the methodology of schizoanalysis as developed by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari to understand the move of urban design practice from a bureaucratic discipline to one of marketing and branding urban space in concert with consumer preferences and desires.21 Schizoanalytical Modelling for Urban Design will re-examine the experience of the Forum in Rome, Ground Zero in New York and Bangkok's central shopping district as both the production of local urban artefacts and the recoding of urban imaginations and identities in a globalising world of disjunctive flows. While archaeology presents a methodology of layering urban models, and genealogy presents an analytical approach of diagramming patterns of urban processes over time, schizoanalysis examines the multiplicity of urban experiences in cross-sectional perspectives where one can observe simultaneously the production of symbolic space and its reception by individual sensorial perceptions. By modelling layered urban space in moving drawings, the urban designer is able to model not only the space of representation, the glittering surfaces of the global city, but also the representation of space, how urban space is appropriated, adapted and reformed. Much like a wall section reveals the constructional aspects of a building, the schizoanalytical urban section reveals how the global staging of the urban spectacle is constructed, perceived and imagined.

Genealogical model of Manhattan's high-rise business districts looking west. The z-axis is a timeline from the 1890s to the 1990s.

Schizoanalysis challenges singular subjectivity and truth in three ways:

(1) Seeing and saying: some urban sites and many urban relationships are imperceptible to the eye and urban experience is indescribable in both words and representations. Like the camera's expansion of the optical capacity of the human eye, the ability to render in wire-frames, transparencies and translucencies allows the designer to adjust according to new optical information: physical relationships between inside and outside, under and over. Cinema language, as described by Deleuze, can create ‘thought images’ through the interrelationship between movement, effect, sound, image and time.

(2) Connecting signifying areas: schizoanalysis operates in social, cultural, political, artistic and scientific contexts. It contains the spatial analysis of how demographic, economic or environmental information can be read or perceived in urban space. However, it is fundamentally a meta-modelling technique that transcends single disciplinary lenses.

(3) Aberrant movement and synchronic time: computer multimedia and modelling programs map the city in time - historically (the past), experientially (the present), and possibly (the future). Animations examine historical development, documenting and simulating street-level urban experience, and creating time-based scenarios for imagining the future of the city. New relationships will be discovered through reversals, speeding up and slowing down. Aberrant movements and non-linear time images are preferred methods rather than simulating ‘natural’ perception through hyper-real simulations and walk-throughs.

Chapter 6, Desire, looks in greater detail at the emergence of the hyper-complex shopping district surrounding a royal palace, a Buddhist monastery complex and a canal-side Muslim settlement in the heart of Bangkok. While archaeological and genealogical modelling reveals the transformation of the city over time in relation to site and programme, schizoanalytical modelling examines the human imagination in relation to the conflicting forces of localisation and globalisation. A theory of simultopia will be introduced to refer both to the theories of simulation and the simulacra of Jean Baudrillard,22 but also to the simultaneity of forces embedded in locality and desires projected forward to experimentation, imagination and the always new. Denise Scott Brown, Robert Venturi and Steven Izenour analysed the experience of American pop culture, consumerism and the iconography of the Las Vegas strip at the different speeds and scales of the pedestrian and the car.23 Their work will help us to look at the emergence of Bangkok's central shopping district as an urban assemblage in relation to three references: the production of the connective architecture of urban armatures, the recoding of the disjunctive architecture of enclaves and the consumption of the conjunctive architecture of heterotopias.24

Schizoanalytical model as a sectional cut through Bangkok's central shopping district showing the connections between parking, interior atria and the mezzanine of the elevated Skytrain over Pathumwan Intersection.

Possible Urban Futures

War, trade and desire encapsulate the conflicting architectures of contemporary globalisation. The identity of urban life as the production of difference is more and more challenged by recent events. In the US, discourses on ‘Homeland’ and the ‘War on Terror’ have initiated a restructuring of cities from heterogeneous places based on the production of difference: ‘… boundless mobility and assimilation and a national “melting pot” identity’25 to homogenous constructions of “homeland”’.26 At the same time, Orientalist constructions of ‘foreign terror cities’ are dehumanised by remote imagery and the news media. The tremendous allocation of resources to promote and conduct these two arenas of warfare has left us vulnerable and ill equipped to engage the enormous restructuring of urban space in order to address the social challenges unleashed by unparalleled circulation of media and migrations and the enormous challenges of global climate change.

New urban design practices aided by digital technologies must directly address the rhetoric and ideology behind this interlinked web of social, political and ecological problems. Digital modelling for urban design can play a crucial role in creating and providing the design tools to reverse the trend in the current imagination away from a permanent threatscape and towards a space of collective opportunities for change. Crucial in unpacking the mediated rhetoric which constitutes the current geopolitical context is to question the urban fly-through simulations, GIS and surveillance technologies in order to construct counter representations of cities and environments. Reversing the homogenising project of ‘Homeland’ requires tools for understanding urban spatial heterogeneity and city life as difference rather than unity and order; disjunctive flows and processes rather than unifying form in an abstract sense; logics of resilience and adaptation in temporal contexts of unpredictable flux; and finally, a full engagement in a broad spectrum of social actors and agents towards facing rather than fortifying against perceived challenges and threats.

Finally, in conclusion, the book looks forward at the two radically different urban futures of India and China. These historically rich, geographically vast and rapidly urbanising countries will dominate the 21st century, and the final chapter of this book argues how digital modelling for urban design using archaeological, genealogical and schizoanalytical approaches can help us to situate the future of urban design practice globally. Here, Arjun Appadurai's concept of the cultural dimensions of globalisation as constructed within a context of disjunctive flows will frame a brief outline of my experience as part of collaborative residencies in both countries with the New School's India China Institute.27 The transcultural and transdisciplinary collaborations in India and China and the trilateral discussion on urbanisation and globalisation between Fellows from the US, India and China provide the basis for furthering the tools developed In this book by applying them towards the production of difference rather than the homogenisation of urban space.

New construction along the ancient Grand Canal in Hangzhou, China.

Acknowledgements

This book would not have been possible without the continued support of Helen Castle, Commissioning Editor at John Wiley & Sons in London. The pedagogical thinking in this book was begun at Parsons, the New School of Design, Department of Architecture, initially under Susana Torre, Department Chair, but was more fully developed in a course called Digital Modeling for Urban Design taught both in the Masters of Science and Urban Design Program at Columbia University's Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation under the direction of Richard Plunz, and in the Masters of Urban Design Program at Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok, directed by Banasopit Mekvichai. In urban design practice I wish to thank Mark Watkins of urban-interface, LLC, and Victoria Marshall and Mateo Pintó of Till, LLC, as well as Steward Pickett and Mary Cadenasso from the Baltimore Ecosystem Study and Morgan Grove and Erika Svendsen from the US Forest Service and the National Science Foundation Long Term Ecological Research Program.

Research in Bangkok was initially supported by the Fulbright Senior Scholars Program at the US State Department. My work there has been long supported by three successive Deans at Chulalongkorn University Faculty of Architecture: Vira Sachakul, Lersom Sthapitanonda and Bundit Chulasai. I am especially grateful to Professor Naengnoi Suksri for patiently describing the physical historical development of Bangkok over the course of many weeks and for poring over old maps, and to Pinraj Khanjanusthiti who, as Deputy Dean of International Affairs, first secured access to the National Archives and Royal Army Survey offices. Former Director of Architecture, Bundit Chulasai supported the construction of the digital model of the Bangkok central shopping district illustrated here, in a course co-taught with Mark Isarangkun na Ayuthaya, Terdsak Tachakitkachorn and Kaweekrai Srihiran. The model was created by Chaiyot Jitekviroj, Kobboon Chulajarit, Krittin Vijittraitham, Nara Pongpanich, Pornsiri Saiduang, Ratchawan Panyasong and Yuttapoom Powjindom. Additionally Pirasri Povatong and Danai Thaitakoo have consistently contributed helpful insights and support in Bangkok.

The overview of the current urban development in India and China in the concluding chapter was made possible by a Faculty Research Fellowship at the New School's India China Institute (ICI). I wish to thank the Senior Advisors of ICI, Ben Lee and Arjun Appadurai, whose vision is behind this institute, as well as the support of ICI's Senior Director, Ashok Gurung, and the first cohort of Fellows from India and China, Amita Bhide, Hiren Doshi, Chakrapani Ghanta, Partha Mukhopadhyay, Aromar Revi, Wu Xiaobo, Yao Yang, Guo Yukuan, Wen Zongyong, and Yang Zuojun as well as New School faculty Jonathan Bach, Vyjayanthi Rao, and Colleen Macklin. Anita Patil-Deshmukh, ICI Senior Advisor and Representative in India, and Jianying Zha, ICI Senior Advisor and Representative in China, were wonderful hosts in each country. Victoria Marshall was an inspiring partner in difficult fieldwork in Hangzhou's urban villages.

Earlier research in this book has been assisted by many people. The basis of the cartographic and archival research work in Rome and New York was assisted by Ana Marton, John Wiggins, Sharon Haar, Jamie Malanga and Antonio Palladino, and Bangkok's shopping centres were introduced to me in 1995 by Bualong Monchaiyabhumi. Dennis Dollens published Transparent Cities following an introduction by Mark Robbins. Initial research was also supported by the Kaskell Fellowship for Alumni of Syracuse University School of Architecture. Publication of Transparent Cities was supported by the National Endowment for the Arts and the New York State Council on the Arts.

Manhattan Timeformations was commissioned by Carol Willis, Founder and Director of the Skyscraper Museum in New York, and supported by a New York State Council on the Arts Technology Initiative Grant. Lucy Lai Wong and Akiko Hattori assisted in creating the computer model of Manhattan's skyscrapers and the interface was designed and developed with Mark Watkins. This digital model was further developed as part of an artists’ residency co-sponsored by the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council and the World Financial Center. John Cadenhead and Erwin Hisan were modelling assistants with the support of Peter Wheelwright, then of the Department of Architecture at Parsons. Grahame Shane, Deborah Natsios, Victoria Marshall, Joel Towers and Petia Morozov - colleagues at Columbia and Parsons - provided constant criticism and support for the work. The computer models and illustrations generated specially for this book were done with the assistance of Asis Ammarapala, Vicky Pang, Kheerti Kobla, Yuttapoom Powjindom, Stan Gray and Raymond Sih.

Endnotes

1 http://www.national911memorial.org

2 Thomas L Friedman, The World is Flat: A brief history of the twenty-first century, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005.

3 Critical Art Ensemble, Digital Resistance: Explorations in Tactical Media, Brooklyn: Autonomedia, 2001, p 85.

4 Kevin Lynch, Good City Form, Cambridge: MIT Press, 1984, p 277.

9 David Grahame Shane, Recombinant Urbanism, London: John Wiley & Sons, 2005, p 113.

10 Brian McGrath, Transparent Cities, New York: SITES Books, 1994.

11 www.skyscraper.org/timeformations

12 Brian McGrath, ‘Bangkok CSD’, Regarding Public Space, New York: 30/60/90, Vol 9, August 2005.

13 Arjun Appadurai, Fear of Small Numbers, Durham: Duke University Press, 2006.

15 Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle, translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith, New York: Zone Books, 1995.

17 Michel Foucault, Archaeology of Knowledge, New York: Routledge, 2002.

18 Aldo Rossi, Architecture of the City, translated by Diane Ghirardo and Joan Ockman, Cambridge: MIT Press, 1982.

20 Eugene Holland, Deleuze and Guattari's Anti-Oedipus: Introduction to Schizoanalysis, London: Routledge, 1999, p 58.

21 Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1983.

22 Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, translated by Sheila Faria Glaser and Brian McGrath; ‘Bangkok Simultopia’, from Embodied Utopias: gender, social change, and the modern metropolis, edited by Amy Bingaman, Lise Sanders and Rebecca Zorach, New York: Routledge, 2002.

23 Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour, Learning from Las Vegas, Cambridge: MIT Press, 1972.

24 Félix Guattari, The Anti-Oedipus Papers, edited by Stéphane Nadaud, translated by Kelina Gotman, Semiotext(e) Foreign Agents Series, Cambridge: MIT Press, 2006.

25 A Kaplan, ‘Homeland Insecurities: Reflections on language and space’, Radical History Review 85, 2003, pp 82–93.

26 Stephen Graham, ‘Cities and the “War on Terror’”, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Vol 30.2, June 2006, pp 255–76.

27 Arjun Appadurai, Modernity at Large: the cultural dimensions of globalization, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996, http://www.newschool.edu/ici/