Directing Television Commercials

I directed hundreds of commercials in my twenty-five years as a director. I directed spots for clients such as McDonald’s and Taco Bell and Porsche-Audi and Wells Fargo. In 1976, I founded Linsmanfilm and soon became a favorite director of the largest producer of commercials in the world, the multinational packaged-goods manufacturer Procter & Gamble. I worked on dozens of P&G brands worldwide, specializing in baby spots (Pampers and Luvs), which I shot in New York, London, Milan, Moscow, Hamburg, Prague, Budapest, Kuala Lumpur (Malaysia), Manila, and Beijing. During that period, I was known as the “baby director.” I also directed dozens of Honda and Acura automobile spots, switching to “sheet metal” in later years, shooting exclusively in Southern California.

For the past twenty years, I’ve had the privilege of teaching the next generation of filmmakers, and I’m proud to say that more than 70 percent of my students have gone on to work in media and entertainment—and many of my former students have kept in touch over the years, sometimes just to chat and sometimes for career advice.

I can’t chat with you here, but I can talk about your career as a director.

The best career advice I can give you is this: Make being an observer and a learner a lifelong pursuit. Look at and study people and procedures. Learn the business of film, take in the world around you, and think deeply about collaboration and bringing out the best in others. These are the essentials to finding success and advancing your career in the film industry.

Bill Linsman instructing production students on a field trip to SONY studios

I’ll give you a few other essentials—guidelines, we could call them—that you might consider following while on your journey as a director. But first, I’d like to tell you how commercials come to life and where the director fits into that process.

Commercial Directing 101

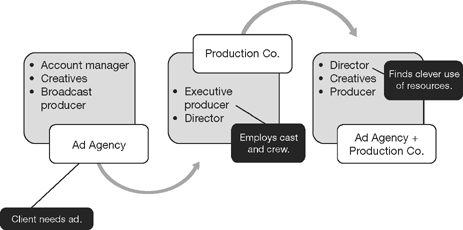

First, a client, a provider of goods or services, requests the expertise of an advertising agency. The ad agency has specialists who handle the business end of advertising. They’re called account management. And the agency has other specialists who handle the creative efforts, the creatives. The account people and the creatives work together to develop a strategy and media message for the client.

The team that conceives of the commercial usually consists of a copywriter and an art director. Their boss is the creative director. This team brainstorms ideas aligned with the strategy aimed at the target audience. The team may come up with a dozen or more ideas and then “short list” them down to just a few.

At this point, a broadcast producer joins the team effort. This person also works for the agency, and he or she knows the production companies who actually make (shoot) the commercials. The broadcast producer also knows the executive producers who own the production companies, as well as the commercial directors affiliated with those companies. How does this agency producer know all of the production companies and talented directors? Experience. But also because a sales rep who works for the production company calls on the agency to keep them informed of new talent and industry trends. So as a director, you’re affiliated with one of these production companies (for example, @Radical Media, Biscuit Filmworks, or Anonymous Content).

At this point in the process, the commercial takes the form of a storyboard or script. The ad agency sends this script to various production companies and invites them to bid on the production, using the talents of a specific director. Here’s where the director gets involved. The ad agency then arranges individual conference calls with the directors to get a sense of their enthusiasm and see what other ideas they have based on the storyboard or script.

This is where competition comes into play. Yes, price is an important factor, but also of great importance are the directors’ ideas. Finally, the agency decides on a production company and director and awards the job. Contracts ensue.

During preproduction, the director creates a shooting board, which formalizes the planned production. The creatives at the agency either approve or alter the plan. Once the agency and production company agree on the plan, they present it in great detail to the client at a preproduction meeting, or PPM. If the client approves, the minutes of the PPM become part of the contract, and the shoot moves forward. The director leads the aesthetic decisions, and the producer (with guidance and help from the assistant director) takes care of the physical needs of the production (equipment, film, crew coordination, location rentals, transportation, food, and so on). On the day(s) of the shoot, the director and crew “cover” the material that everyone has agreed upon. The next day, the agency and director review the dailies, or rushes. If they approve them, postproduction begins.

That’s the short of it, but as you can see it’s a multistep process, and whether a director lands the job has a lot to do with the enthusiasm and ideas he or she brings to the project.

Commercial development process

Enthusiasm, ideas, talent, skills …

You need all of these, of course. But there are some additional things you can do to advance your career. Here are those guidelines we talked about earlier. Pretty simple, but I’ve found these to be crucial over the course of my career.

Guidelines for a Fruitful Directing Career

1. Understand the Finances

Businesses want to make money, and filmmaking is a business—even when you consider yourself an artiste! When you bear that in mind, with thought and careful planning you’ll create a memorable, effective spot and perhaps even save your client money—and that could lead to repeat work. As a director, you want to ward off problems that will be expensive to solve during postproduction. You want to be a partner, not a liability.

2. Work as Hard and as Passionately as You Can

Always give 110 percent. As the Emmy Award–winning actor Bryan Cranston of Breaking Bad (2008–2013) told one of my classes: “Work your asses off, and one day they’ll remember your name.” Conan O’Brien is now famous for his mantra involving work ethic and conduct: “If you work really hard and are kind,” he says, “amazing things will happen to you.” As a director, your hard work and enthusiasm will energize the cast and crew.

3. Always Carry a Notebook and a Pencil

Take notes, or at least mental notes, about everything you see and hear. You’ll be able to use it all at some point—a sound or an image will spark something in your brain, and those notebooks will be excellent resources. As a director, this sort of ongoing homework will enrich your creativity and impress your clients.

4. Take in Even the Smallest Interactions in the World Around You

Notice the light and how it defines these observations. Your observations might be from nature—the sound, smell, and feel of raindrops and how they differ from the sounds, smells, and feel of a downpour, for example. Or they might be mechanical and practical—would the audience be better served if an actor enters the frame from above, below, or someplace else unexpected? As a director, you must think like a writer, a producer, an art director, a cinematographer, even a member of the audience.

By the way …

Ideas are everywhere, sometimes where you least expect to find them. Here’s an example from my life. I was in Manhattan, calling on creative executives at ad agencies near Grand Central Station. It was a day or two before Halloween, and street vendors were hawking a slew of scary toys. One in particular caught my eye: a plastic hand on a base that turned at the flip of a switch. I bought it. When I came home, my wife thought I was nuts.

A week later, a client sent me a storyboard featuring a fifties rock ’n’ roll band. Soon after, as I was getting a haircut, the barber began to show me photos of some of his ’dos. A lightbulb went on, and I wondered, Could you hide some sort of mechanism in a pompadour? I was thinking of the 1950s Elvis, and of James Brown …

I hired the hairdresser, removed the mechanism from that silly plastic hand, and voilà—the actor’s hair bobbed to the music. It created a huge surprise and the client loved it. As a director, stay open to the serendipitous world.

5. Study Everything

In addition to all the facets of filmmaking, read science, philosophy, the literary classics from a variety of countries, mythology. Try your hand at different trades, and take the time to learn their jargon. James Cameron studied physics in school and made a living as a machinist and later as a truck driver. His passion for outer space and deep ocean exploration has led to him working with renowned scientists and engineers, developing architectures for expeditions and conservation projects. As a director, at some point and in some way, you’ll use aspects of your assorted interests and knowledge—and in so doing, you’ll create in your films a many-layered reality.

6. Keep Viewers Engaged

Startle them with surprise. Make them sit up because you shot from an unusual angle or created a music cue or a sound effect. Use staging, blocking, and framing to keep the audience on the edge of their seats. Understand how to put images together; understand the art of cutting. As a director, always think about transitions—from shot to shot and from scene to scene—with the goal of propelling the action and keeping the audience wanting more.

7. Please Your Clients, but Stay True to Your Aesthetic

Years ago I asked an agency producer for feedback. Her response: “You’re too accommodating.” This wasn’t what I expected. What did she mean? Yes, you must consider the client’s needs, but the same is true for you as an artist. Clients are paying you for your creative perspective. As a director, present your ideas and flesh them out so the people who’ve hired you can visualize and discuss them. But fight for what you believe will best serve their product.

Bill Linsman on a Kmart shoot

8. When You Make a Mistake, Learn From It

You won’t be the first to make a mistake, and no mistake you make will be a first. If you make an error, own it, figure out why it happened, do what you can to correct it, and try never to repeat it. Robert Rodriguez once said that we all make half a dozen awful films—we just have to get them out of our system. As a director, keep shooting. Even if you have to do some work for free, do it. Be active and look for opportunities—student films, webisodes, spec commercial work. You’ll learn, and in the process, you’ll make a name for yourself.

9. Watch Every Movie You Can

Every one of them—the amazing, the good, the mediocre, the awful—has something to teach you. Time is irrelevant. Don’t think a director who worked fifty or sixty years ago has nothing to say. Citizen Kane came out in 1941, and Casablanca was released in 1942. All you have to do is watch them to see the proof—and then watch them again and again. The master directors Quentin Tarantino, Steven Spielberg, and Martin Scorsese all have said that they saw every movie they could. Do what they did—and be sure to watch their films numerous times.

There are many ways to look at a feature, a documentary, a short, a cartoon, or a commercial: You can view with the eye of the paying public, as a client, as a consumer, or as a director. What gets your attention? What breaks your heart? What inspires you? What makes you laugh out loud? What reminds you to buy a product or lures you to switch brands? Be aware. Be a learner. As a director, strive to be knowledgeable about what has gone before. That way, you can be creative not just in the present but also in the future.

10. Seek Out and Meet People in Every Profession

Everyone has something to offer, if only you show interest. Really, that’s all it takes to get someone talking, explaining, or showing you around. Be courteous and enjoy people’s company. Travel agents, cake decorators, upholsterers, printers, artists, sound designers, realtors—they all have a wealth of information to impart and stories to tell. When you observe and listen, you’ll get the lingo, the dress, the philosophy, and a sense of their pride in their work (or their distaste for it). Take mental notes. As a director, everything you learn adds flavor to your repertoire of skills. Learning about and getting to know people can help you cast for a particular profession or set up a scene.

11. On Set, Establish a Warm, Positive Environment

Be a nice person to be around. You want cast and crew to look forward to working with you. Make the first move: Introduce yourself and shake some hands. Learn first names—that applies to every member of the crew, to the caterers, the background players, as many people as possible. On breaks and lunch, you won’t be able to socialize much, but make an effort. Join conversations. Listen when people talk about their children, or sports, or their concerns. Then, ask questions.

As a director, you set the tone for people’s jobs, whether for a six-month feature or a two-day commercial shoot. Your approachability and genuine interest in your cast and crew’s lives will create an atmosphere of collegiality, teamwork, and value—and that will project onto the screen.

12. Take Chances

Because you’re a craftsman, sometimes the heart is more important than the rules, and the gut is more important than protocol. Experiment with setups, casting, and alternate reads (after you shoot the required lines). If the writer is on set, ask if she minds trying some improvisation (always respect the writer!). While you’re shooting, seize what you can—for example, let the recording medium roll for a minute after you say “Cut.”

In the documentary Hearts of Darkness (1991), which tells the story of the making of Apocalypse Now (1979), we see that when the wet season approaches where they’re shooting in the Philippines, instead of folding up camp, director Francis Ford Coppola allows the weather to play an important role, just as it did during the Vietnam War.

As a director, don’t be thrown by the unexpected. Instead, welcome it as your friend.

13. Encourage Suggestions

A director has limited time to chat, but if you’ve created a collegial atmosphere, once in a while a member of the crew will have an idea worth your consideration. Listen—it could turn out to be brilliant. And whether or not you use it, thank the person. If you do use it, thank the person again, in public and privately. As a director, you’re the leader of a team, but remember that even a defensive end can score.

14. Let People Do Their Jobs

I can assure you that no one likes to be micromanaged. For example, don’t tell the director of photography how to warm up the color temperature. That’s a sure way to antagonize a professional. Value the expertise the crew brings to the table. When it’s appropriate for you to give direction, rather than issuing an order, describe what you want to convey. Which of the following would you respond to?

“You, put the 18K over there and the bounce board over here.”

“Julie, I want to evoke the feeling you’d have waking up to a lazy summer morning—something akin to that magazine ad we talked about.”

The first will lead to resentment, and the second will have Julie and her crew jumping through hoops. As a director, treat people with respect and acknowledge their expertise. I guarantee that you don’t know as much about lighting as the DP or gaffer.

Ready for the Next Steps

When you have skills and experience under your belt, it might be time to consider establishing your own production company. I did, because I couldn’t find a company I wanted to work for. So I worked for myself.

First, you need to have a financial cushion. With that in order, all of the above guidelines for success apply, but there are a few more that are specific to being your own boss.

1. Mind the Cash Flow, and Keep the Overhead Low

These are crucial concepts when you decide to operate your own business (they’re important when you’re working for someone else, too). When you get a new client, you’ll be eager to hire another employee or purchase that flashy bit of equipment. But it’s always better to rent. Remember that now you’re the one who has to come up with the cash for the payroll and credit card. And when you’re between jobs, those financial responsibilities can drag you down.

When I started out, I made the mistake of hiring too many staff. Once people are on board, it’s very hard to eliminate their positions. They’re counting on you. As the head of your own company, your first goal is to keep your business afloat.

2. Be an Active Self-Promoter

Who better to get the word out? There are many avenues for advertising your business—pursue all of them. Get your résumé in order. Open your book of contacts and send everyone in it a newsletter or an email blast, and then follow up with another email, write a blog, or pay for a recurring ad in the trade publications. Call your local newspaper and contact business bloggers—a reporter may do a business brief about you or even a feature.

In the developmental stages of my production company, in the days before email, I did it all: I compiled a mailing list and introduced (or reintroduced) myself. I sent periodic newsletters and notes. I tooted my own horn in every way imaginable. I also used profits that I’d made from the business to buy $43,000 worth of advertising ($100,000 in today’s economy) in trade magazines, primarily Shoot, a weekly tabloid.

I was a small operator, but the advertising and press releases and newsletters got my name out there. The barrage worked so well, in fact, that when I walked into an office in Los Angeles or New York, everyone—from the receptionist to the executive producer—knew who I was.

Promotion, promotion, promotion. This is no time for modesty. As the head of your own company, getting your name out is a priority. Clients will follow.

3. Have Fun

This is true whether you’re an aspiring director or a seasoned pro. You know the budget, the concept, what you want to do, and how to get it done. You’ve created an environment where people feel respected and everyone around you looks forward to the creativity of their work. But what about you?

Intensity is important, but only in small doses. Leave the brooding intensity to an actor. Enjoy yourself. Keep in mind what gives you satisfaction and makes you feel good about your work. When you enjoy your job, your environment, and the people you work with, you can endure those moments when nothing goes right—the light fails, a prop breaks, an actor has trouble with lines, the head of the studio pays a visit, or the occasional fourteen-hour day …

What a privilege it is for us to be part of the film industry. What a privilege.

Bill Linsman

Photo by Dave Green