Discovering the leader in you is an ongoing process, not a one-time, isolated event. After working through the first six chapters, you have probably accumulated many insights about yourself, your challenges, and your opportunities as leader. This final chapter helps you develop a clearer picture of yourself as a leader now and in the future. It outlines a process that begins with mapping information on the leadership framework by which Chapters Two through Six were organized. You'll begin with brief phrases that you'll subsequently expand and eventually incorporate into holistic statements of purpose and, finally, a letter to yourself.

This chapter also presents a process you can use to work through any major impending decision you face in considering a larger leadership role. Furthermore, you'll gain some advice on how to enhance, support, and extend your discovery process of why, when, where, and how you may lead.

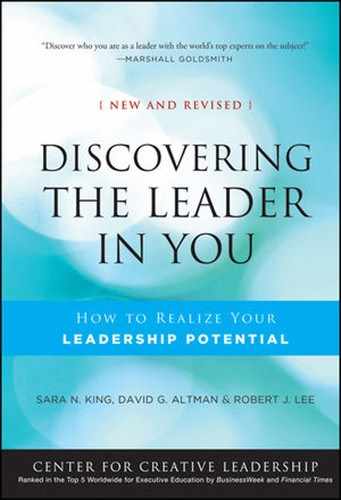

Let's return to the Discovering Leadership Framework we introduced in Chapter One (Figure 1.1). This framework helps you assess the context in which you lead, analyze your specific leadership dilemmas, and identify specific themes and patterns that have an impact on your effectiveness as a leader. Figure 7.1 uses the framework to highlight the key concepts from each chapter as a reminder of what was discussed. We hope these key concepts will remind you of your thoughts as you read each chapter.

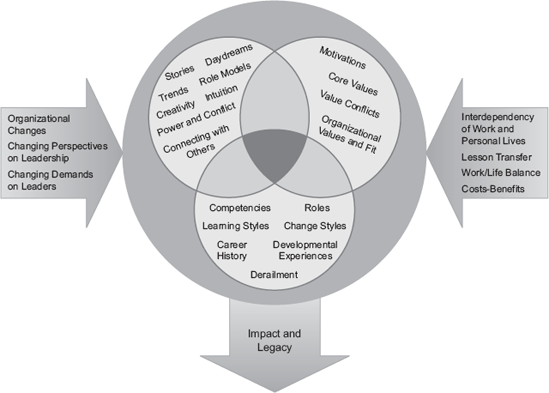

So that you can use the framework to capture salient ideas, thoughts, and insights about yourself and your situation, we've posted a blank version at www.josseybass.com/go/discoveringtheleaderinyou. If you are not able to download the blank copy, sketch the framework on a sheet of paper, and fill it in as you work your way through this chapter. To help you get oriented, Figure 7.2 illustrates an example of a leader who shared with us how he used the framework to guide his leader discovery process.

Take a few minutes now to write the most pertinent words or phrases in each section of the blank version you downloaded or sketched for yourself. For example, in the organizational realities section, you might list the key issues in your organization. List those things that are affecting your leadership the most, such as the key technological trends, the financial health of your organization, factors related to a pending merger that is threatening leadership jobs, growth pressures on your organization, notes about your boss's recently vacated position (which you might consider taking), or other contextual issues.

Similarly, in the section on vision, focus on the role that leadership plays in your life, and include phrases describing your leadership vision. As you fill in each section, refer to Figure 7.1 for key topics or revisit the previous chapters to bring back ideas that came to you as you read each one. Your responses to the questions at the end of each chapter should help you as well.

Next, step back and reflect on what you've written. What connections do you see between various thoughts within each section and between one section and another? For example, do you see a connection between your main view of leadership (Chapter Two) and your leadership competencies (Chapter Five)? How do your core values (Chapter Four) relate to your ideas and choices about role models (Chapter Three)?

Look for leadership themes in your initial reflections. Suppose your view of leadership and your motivation for leading are related to service and you picked "nurturer" and "facilitator" as preferred leadership roles. From that you might distill a leadership theme of "giving to others." Or suppose that getting things done through others is one of your strong competencies, that you favor the role of coach, that one of your core values is diverse perspectives, and that your vision incorporates a desire to lead in a global context. From that pattern, you might cull a theme of "global leader who maximizes the potential of a diverse workforce."

Now step back further to see if a picture emerges from your framework as whole. Do you like what you see? Does it align with your current leadership role or with a different role you might be seeking? What core issue needs attention? Does this picture describe the impact you wish to have?

Did you write much more in some sections than in others? Are some pieces missing? If so, access another blank framework, and create the portrait of your ideal future. Pick a future point in time (say, three years from now), and press yourself to write in each section. Do you expect the organizational context around you to have changed a great deal? Write a phrase to capture that future context. Do you envision significantly different leadership roles? Write them down even if there is no guarantee that they will be available to you. What competencies—old and new—will need to be in your leadership profile? And so on for all five sections. What implications can you draw from this future version of the framework for your development as a leader?

In this part of the chapter, you will use the work you carried out in the framework's sections to generate new key statements about yourself as a leader. We challenge you to come up with five or six. From these statements, you can further define how leadership fits in your life.

Here are some key signature lines written by senior leaders who have worked with us:

"I prefer building a team and seeing what we can accomplish together."

"I just can't sit back when there is leadership work to be done. I find it rewarding to fix things."

"I need my privacy. If leadership means living in a fishbowl all of the time, then I don't think I am interested."

"What turns me on is winning. I love it when we beat the competition or end up high in our industry's rankings."

"I can't take on a larger leadership role at this time. My plate is full between work and family responsibilities. I am comfortable staying in an individual contributor role."

"I am at my best when I coach others. I would like to help the organization more by building the next generation of talent."

"I get energized by helping people solve their problems."

In writing your own five or six statements, do you see any additional themes? What self-revelations or self-confirmations do the themes suggest? Self-revelations are new insights that arise from this discovery process. Self-confirmations identify core capabilities or values that you already knew but now can hold with more clarity and conviction. Test each of your key themes for insights.

A service-minded leader's confirmation might be, "I won't be totally satisfied in a leadership role unless I am in a servant leadership role." For a leader whose vision includes a global component, a revelatory statement might be, "I need to find a leadership role with opportunities to lead a globally diverse team to deliver a socially responsible product or service." Although this exercise won't always result in a major eye-opening revelation, often you will come up with an insight that has been right under your nose.

Each statement tries to say, in essence, "Here's where I stand. This really matters to me. The place that other things find in my life will depend on their fit with this." You'll know when you've hit on an authentic statement when you share it with your spouse, your parents, or your best friends, and they confirm it reflects the real you. The statements you write will move you closer to a central statement of purpose.

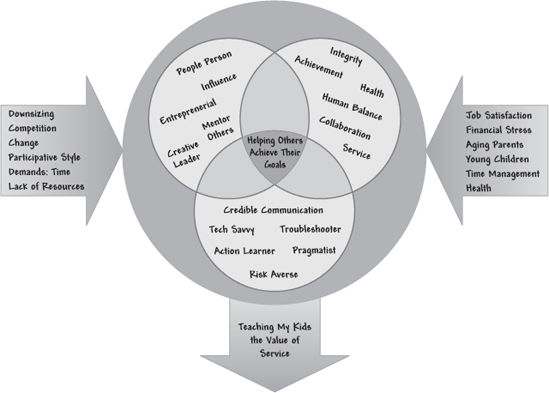

Now look at Figure 7.3. At the intersection of vision, values, and profile appears the word purpose. Reflect on your leadership vision, your core values, and your signature strengths (where you really excel), and try to write a sentence or two about your leadership purpose. As a leader, what do you really want to accomplish? What is so important to you that you are determined to make it happen? Refer back to Figure 7.2 to see the overall purpose as written by one senior executive. Here are some examples:

"I want to start a new program for underprivileged children."

"I want to develop the talent capacity in our organization to meet the challenges we face in the next three to five years in a way that we are perceived as best-in-class."

"I want to become president of my division in order to have the influence and impact I envision."

"I want to lead the corporate philanthropy efforts in our organization."

As you reflect on your purpose statement, consider closely the impact and legacy parts of the framework. Your overall leadership purpose, when accomplished, will be the impact you have and often the legacy you leave. Don't rush through this part. Take time to reflect, and imagine yourself making the kind of difference you want to make. Does your purpose lead to the impact you wish to have? What do you hope others will say about your leadership?

Now that you've filled in the framework (both current and future), articulated some key statements about your leadership, written an initial statement about your leadership purpose, and reflected on your leadership legacy, let's use another process for describing the future.

For this process, we'd like you to write yourself a letter. We have found that when people use different methods in their discovery process, they produce higher-quality insights than when they use only a single approach. By completing the framework, you captured the essence of who you are and came to better understand the context in which you lead. By completing the future framework, you outlined what you imagine the future to be in each of the sections of the framework. A letter affords you an opportunity to create a picture. In the letter, you can use your creativity to express more fully your hopes and desires related to the leader in you, particularly the future leader.

The letter-writing activity will feel different from filling out the framework. In many ways, the letter addresses the gap between your current and future state. What are the important steps you need to take to move from your current framework to your future framework? How might you turn these steps into goals? What do you want to continue doing as a leader, and what new things do you want to incorporate?

We're giving you only two rules for your letter: express your future in terms of clear goals, and name some people you will need to help you achieve your goals. The rest is up to you. Address your letter to yourself, sign it however you like, organize it however you want, and use whatever style of writing you like (a poem, a story, an essay, a correspondence, a journal entry—any style is all right as long as it's comfortable for you). Expand on what you have learned about yourself, push those insights even further, and try to create a compelling, descriptive picture of the future.

Throughout this book, we have included letters or portions of them that senior executives have written during their experience with CCL's Leadership at the Peak program. This is your chance to participate in this powerful activity. Go back and reread some of them (they are all italicized to help you find them easily), or read the letter that follows as an example of what you might write. Your letter can look completely different and can also address different issues. Just use the examples to get you started. Whatever you write, you can always go back and revise it—but don't think so much about that. Have some fun with this activity; let your thoughts flow, and see where you end up.

Dear—

After spending an entire week of introspective thought, I have concluded that there are some things in life that require action. If I am successful in working at these things, I believe it will be beneficial not only to myself, but also to those around me; whether these people are coworkers, family, friends, or new acquaintances.

First, I have learned that my peers at work have a much lower image of me and my capabilities that I ever imagined. I believe I can do a better job of getting connected to them. I will make every effort to gather more emotional input from them before making a decision or striking a position.

Second, I intend to be more productive in giving feedback to my employees on a regular basis. My initial tendency is to operate like a solo pilot in my daily activities. I need to fix this problem because as I advance in my career, the ability to interact with people and provide constructive and critical feedback to help them develop will be essential.

Third, I realize that life is finite. I need to be more aware of my physical and mental well-being as I approach the next decade. I intend to pay more attention to what I put into my mouth and become more selfish about getting adequate sleep and exercise. I will feel better about myself, and that will make me a better person at home and in the office.

Fourth, I intend to address an issue with my parents about being more active in my children's lives. I need to do this because it is a source of stress for me and my family.

Share your letter with individuals you are confident can help you. Make some commitments to them so that they can hold you accountable for achieving your goals and working toward this future picture.

We have said that discovering who you are as a leader is an ongoing process for making the right choices and recalibrating your choices as those challenges change or as you reframe them. From day to day or week to week, your increased self-awareness helps you stay on track and keeps you from drifting. But what about the moment when a decision has to be made? What do you do at the point you are offered your first managerial opportunity or you take a leap into a larger leader role? How should you proceed to make a choice? Consider one story.

Reuben Daniels faced a big decision. He had traveled a predictable yet demanding path through college, graduate school, and early employment as he became a highly qualified clinical scientist. As a more and more accomplished clinical researcher (with both an M.D. and a Ph.D.), with a focus on molecular medicine, he loved doing research and being part of a collaborative lab team. By his late thirties, he had been promoted from senior research scientist to the director of advanced research at the institute where he worked. The institute was affiliated with a university's hospital and medical and other graduate schools. As the director of advanced research, he managed and mentored twelve younger scientists.

Because of his success in the lab, Reuben was named as one of three vice presidents on the institute's executive team. As a result, the scope of his supervision expanded from the 12 scientists in his lab to include about a third of the institute's 210 employees. This enterprise-wide role proved to be gratifying in some ways: Reuben could now set policy direction for a number of units and build a strong cadre of high-potential scientists. But the role also proved irritating: he spent much less time in the lab doing science and much more time in meetings talking about science. Responding to e-mails also took time. In one instance, he became embroiled in administrative conflict around the lack of lab space and the need to bring in more outside funding to support the institute's increasingly lean scientific infrastructure. At the end of most days, Reuben thought the trade-offs he had made between science and administration were worth it, but he wasn't at all sure he wanted any further advancement. This was as far from his beloved lab as he wanted to go.

Two years later, Reuben's boss resigned abruptly to take a position elsewhere. The executive vice president for health affairs called Reuben to her office and asked him to take over as president of the institute. The other two vice presidents would not be candidates; one's health was poor, and the other was clearly in over his head. The job was Reuben's to take or to refuse.

Reuben requested a week to consider. As it happened, he had participated in a week-long leadership development course that included spending time with an executive coach a year earlier. He had done his homework, so to speak, on his values, his life balance issues, and his personal long-term vision. That experience had confirmed his commitment to limit his organizational advancement so he could stay close enough to his research projects and keep up his personal and family life. But now this!

Reuben still had his coach's phone number, and the coach was ready to help. They had long discussions by phone and e-mail about what was important, what Rueben's leadership agenda might be, and how he could best contribute to science and society. How would the president's job affect his ability to stay on top of emerging events in his scientific field? How could he be president of a prestigious institute when he didn't do well as a public speaker and couldn't even keep his own desk in order? Could he handle the politics that sparked the former president's departure? Would he be able to bring in big money or make the staff cuts necessary to align costs with grant revenues? After a week of reflection, Reuben decided to take the job because it would be the capstone challenge of his life. He negotiated executive support for the research agenda he wished to pursue. Since then, and so far, he is doing quite well.

The point of this story is that Reuben assumed the new opportunity by choice, not by default. His decision process included a serious analysis of what looked right for him. He used the knowledge he had about the context in which he would lead, the leadership demands, and his own interests and abilities. He also found a coach—a sounding board—to help him sort out the issues. In the end, he determined that leading the institute fit his future picture and that he was willing to accept the trade-offs.

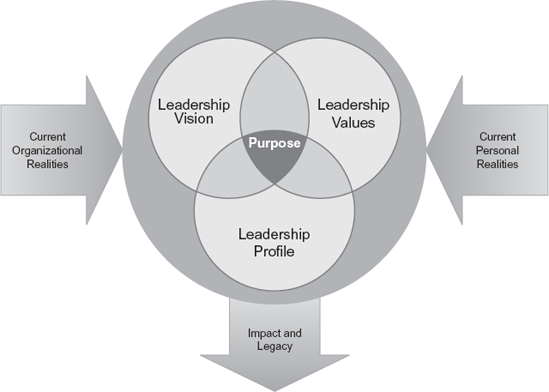

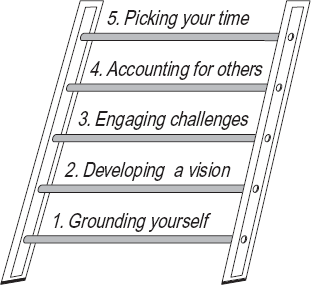

The leadership decision ladder in Figure 7.4 can help you sort out a large decision in a way similar to what Reuben encountered. A ladder is an obvious metaphor for a sequence of steps, and in this case it signifies the stages you climb as you decide whether to take on a leadership role. The ladder embodies the same or similar questions as those in the Discovering Leadership Framework, but it presents a different perspective and a different order to the questions. Such small changes can present new insights. Consider that:

Wherever you are on a ladder, there is potentially another step to take.

When you look down at previous rungs, you are reminded of choices you made in getting to the rung on which you now stand.

Your vantage point and view of the surroundings (the context surrounding your leadership) are slightly different at each step on the ladder.

The ladder has five rungs, each representing a point of connection between leadership choices you have made in the past and the context surrounding those choices. In thinking about how you relate to this ladder, you may find that you are moving up the ladder toward more leadership responsibility in a relatively concerted way or that you have paused on one of the rungs as you postpone further leadership commitments. You might conclude that the view you have from the rung you're on is just right; staying where you are provides you with what you need at a particular point in time.

Of course, it's not realistic to think that your leadership capacity is defined along just one set of rails and rungs. Other leadership ladders appear in other situations and times in life, at work or at home, in your community, or in unfamiliar places. You can also always step down from one leadership ladder to climb another that appeals to you more. You can move up and down any leadership ladder as you need to revisit decisions and accomplishments, recall the perspective from lower down, remind yourself of the stages you've gone through and choices you made to get to your current position, or simply recheck the sturdiness of those lower rungs as they support all the rungs above. No matter what leadership ladder you're on, your ultimate goal is to make decisions from the highest rung, where you have the best view of all the circumstances that you currently face. Here is what each rung represents in the decision to lead:

Rung 1: Grounding yourself. This rung represents basic self-knowledge about your personal vision, values, and competencies. At your core, who are you, and how do these core factors affect you as a leader? Throughout your career and life, you will stand again on this first rung, updating your self-knowledge, reevaluating it each time you assess whether a new opportunity is worth pursuing. Occasionally standing on the first rung is a good way to reconfirm your purpose as a human and the authenticity of your leadership journey.

Rung 2: Developing a vision. What is your vision for leadership? What do you want to accomplish, and how will being a leader help you? Do you have something more to offer the world: a skill, a message, or even a different reality? Is there some specific impact you want to make? This could be your overall purpose as a leader, and it serves as a basis for where you want to go with leadership. Looking down at the work you did on rung 1, think in personal terms about what you have to say or want to express about yourself as a leader. How will a new opportunity to lead help you accomplish your ultimate purpose in life? Many people's purpose becomes cloudy and hard to define as new variables come into play. Periodically stand on this second rung to reassess how your purpose can help you strengthen the connections between who you are as a leader and what you want to do in that role.

Rung 3: Engaging challenges. This rung is where curiosity, adventure, and challenge come into play. What new things about leadership would you like to learn or try? What might be missing from your repertoire that you'll need in a new leadership position or opportunity? Will a new leadership opportunity provide or allow you the growth, learning, and experimentation that you'll need to improve your skills? At this rung, you need to confront whether you're willing to take on a new challenge; don't assume the answer is always yes.

Rung 4: Accounting for others. At some point in a leader's journey, you realize that your effectiveness is closely tied to the efforts of other people. One executive in his mid-forties recently told us that he finally figured that his success going forward will be a function of how well he works with and through others versus what he is able to accomplish through his own efforts. What do you want to accomplish for and with others or for an organization? If you seize a leadership opportunity, what larger goals will be advanced or fulfilled? How will others benefit from your leadership, and how can they help achieve the changes you desire? Is what you hope to accomplish for and with others realistic? Have you checked to see that the support, resources, job responsibility, and context will work together with your insights to make your hopes for them a reality?

Rung 5: Picking your time. Is this the right time for you to take on a new or expanded opportunity? Is your personal context compatible with anticipated demands such as the scope of the work or the amount of travel it requires? Do you have your family's support? What will be the benefits and trade-offs of this role for people close to you? Will it require a move or changes for others? Will this leadership opportunity open another opportunity that you think you want? If so, is this the step that will take you and the people important to you further? Will saying yes or no now limit your chances or options later?

At the end of the day, each step of the leader ladder requires making concrete decisions. We have some suggestions for you to consider as you move through the decision process:

Sleep on it. Let your insights marinate before making any final conclusions or public pronouncements. Your conclusions may look different after reflection.

Share it. Share your thoughts with friends you trust to be sounding boards and providing honest feedback to you. Confirmation about your discoveries and your plans is welcome. Disconfirming feedback is equally important.

Experiment. Before making any big moves based on your current thinking, try experimenting. Try out some new behaviors. Float an idea past your boss. Volunteer. You don't have to make permanent choices or decisions before you test out your hunches about leading. For example, if you want to think more positively about the situation you find yourself in, try it. Or if you find yourself underchallenged, volunteer to think about another group's current business challenge, and offer advice. Let your experiments inform your thinking.

This chapter (and this book, overall) should have already helped you draw new insights into your journey and development as a leader. Perhaps you are redefining where and how you want to lead. You may decide right now that you are ready to take on a leadership role or advance into a larger one. Or maybe you want to continue with self-discovery and see how you can maximize your development in place. Perhaps you don't want a new role; you just want to keep from getting stale or bored in the one you have.

Wherever you are right now, we think it's worth taking a little more time to clarify (or further clarify) your goals and tap into your social network for advice and support.

In the letter to yourself, you outlined some important goals. We assume you already know a lot about setting goals and techniques for making them specific and measurable. You also know that to set yourself up for success in achieving your goals, you must begin to articulate the details of an action plan. The action plan must have deadlines, the resources you will need to accomplish your goals, ideas for overcoming obstacles, and a list of benefits you will accrue. To help confirm that you are targeting the right goals and that they are clear, consider these questions:

How has this discovery process helped you be more certain about your role as a leader? Where do you still have uncertainty? What else do you need to help you?

Do you still see yourself drifting? Do you want to tackle the problem of drift? If so, what tactics will you use to get out of drift?

Do you identify more now with yourself as a leader? Do you imagine taking small moments to exercise leadership as well as pursuing additional formal roles of leadership?

What other information do you need to help you clarify what you've discovered about the leader in you?

Are you stuck on a particular rung of your leadership decision ladder? From whom do you need more help to get unstuck?

Wherever you see a gap, unfinished work, or an unreached desire, this is another place where you need to set goals. Also, don't forget to think in concrete terms about how accomplishing these goals will help you in your journey as a leader and how you will measure your success. You don't need to do all this on your own; in fact, it's important to seek the advice and assistance of others.

You gain little or nothing from making this journey toward greater leadership alone. There are many ways to get help; one of them is through formal and informal feedback from other people. It's rare to get the opportunity to see yourself as others see you. Honest feedback from members of your network can help you confirm that the goals you have set for yourself are the right ones. Feedback can help you know how the changes you seek for yourself may come across as beneficial or disruptive to other members of your organization and even to your family and friends. Feedback can also help you evaluate setbacks or opportunities.

Because taking a leadership position often means trading away honest feedback (the higher your position, the likelier that people will tell you what they think you want to hear rather than what you need to hear), you will have to work hard to provide an environment in which people feel safe to give you the feedback you need. One place to look for that kind of feedback is in the safety of your developmental relationships (with coaches, mentors, and role models).

There is no prototypical developmental relationship, and there is no single role or combination of roles required to make a relationship developmental. Since that's the case, we urge you to seek out multiple relationships that can fuel your development. Figure out what you need developmentally, and then consider who can best help you fill that need. Embrace those around you who will give you honest feedback. At CCL, we encourage feedback that is totally kind and totally honest. If you can find people who give you that kind of feedback, consider it a huge gift. The key is to match the right relationship to the right need. For example, if you think you want the next formal leadership role above you, talk with people who hold or have held that position. Ask them about the strategic priorities in the role, its demands, what they like and dislike about it. Of course, if this person is your boss and may feel threatened, be savvy about finding someone comparable who does feel comfortable sharing his or her point of view.

Seek out skeptics so that you are forced to consider all possible perspectives on the decision. A developmental relationship with someone who thinks very differently than you do can be of great benefit, especially if you value his or her point of view. Or consider working with someone who is good at a particular competency that is still a stretch for you. For example, individuals often get promoted into a leadership role because they are excellent doers. They get the job done and do it well. However, they don't always know much about getting work done through others and developing other people. If that were your situation, you would want to seek out someone who is particularly good at spotting talent, setting development plans, and giving targeted developmental feedback.

Developmental relationships need not be long term or intense. What you're looking for is simply a different perspective, for example, or new knowledge, a willingness to engage with your ideas, a measurement of your capabilities, or just a good listener who keeps you motivated. Lateral, subordinate, and even relationships outside work can all be developmental. An experienced colleague, a peer in another division, or even the retired executive who lives down the street may be a good match.

Cynthia McCauley and Christina Douglas (2004) identify different types of developmental relationships. Here are five that might particularly suit your leadership discovery process.

This is a colleague or group of people with whom you can discuss your satisfactions and dissatisfactions about your leadership role. As a sounding board, the person might simply listen as you think aloud about vision, values, self-awareness, and other aspects of your leadership; or it might be someone to whom you can pose specific questions, like, "I believe I act in tune with my values, but what have you noticed about my actions that might tell a different story?" or "Do I come across as unmotivated? What gives you that impression?"

A sounding board should be someone you see on a regular basis and is willing to listen to you carefully. Look for someone who is good at thinking out loud and considering alternatives, and a person you can trust to understand and appreciate your uncertainties.

A counselor encourages you to explore the emotional aspects of your work. He or she can, without judging, let you vent and express your frustrations and negative emotions. For instance, perhaps you doubt your capacity to develop and sustain a leadership vision because that kind of thinking has always made you uncomfortable—you have always left the pie-in-the-sky thinking to others. But as a leader, people expect you to express a vision, and they want to know that you have one. Now you must deal with your impatience about something that you have previously regarded as impractical, unnecessary, or even nonsensical.

A counselor can help you take a different perspective so that you can adapt and develop a capacity you previously ignored. For this role, choose someone you can trust as a confidant—someone who is empathetic and objective but also clearheaded enough to see through the excuses you make and call you out for procrastinating.

This supporting role provides valuable encouragement and affirmation. Seek out someone who can express confidence and affirm and celebrate your accomplishments. Such a person might take you out to dinner to celebrate a milestone, or join you on a fishing trip or some other excursion when you choose your leadership opportunity. When looking for a cheerleader, ask yourself who around you always makes you feel competent. Look for someone you can share your small successes with or someone in a position to reward your accomplishments.

Where would Lewis be without Clark? And where would their Corps of Discovery have ended up without Sacagawea, a native Shoshone, accompanying the group as a knowledgeable companion? In terms of discovering the leader in you, companion refers to someone who can accompany you on the journey. If you know someone else who is engaged in self-discovery as a leader, consider asking him or her to share experiences with you. Each of you can discuss such things as your respective development progress, how each of you arrived at this stage in your development, and where each of you plans to go from here. This kind of relationship will make each of you stronger and more resolved as you share stories of struggle and success, knowing you're not in this alone. Do you know a colleague who faced a similar situation? If so, talk to that person.

Some organizations formalize and extend mentoring over a period of time. But even in the absence of such a program, there may be a more senior leader in your organization who has already been through a process similar to the one that you are now undergoing and is willing to mentor you. He or she can provide an organizational perspective, linking your developmental quest to issues of talent development, business strategies, and personnel practices. You might find a mentor outside your organization who has had experiences like your own and is particularly interested in helping you define yourself as a leader. When considering someone to become your mentor, be sure to discuss together whether he or she has the time, motivation, and experience to help.

So far in your journey through this book, you have come to some concrete decisions about how leadership fits in your life. You have set some goals, you have thought about the help you need to reach these goals, and now we need to make sure you have an ongoing process to support you throughout your leadership journey. It is important to constantly assess how you are doing in your journey as a leader. Are you on track? Should you step down a rung or two to revisit key dimensions of your leadership? Which performance indicators should you track?

Being a leader requires taking a lifelong perspective on learning, growth, and development. Your goals will undoubtedly change over time, and thus monitoring progress against your goals also needs to be ongoing. There are five key overarching steps in the monitoring process (Hannum and Hoole, 2009):

Articulate development goals in behaviorally measurable terms.

Develop a plan with specific actions and dates for deliverables.

Measure your progress through systematic collection of data using a variety of data collection tools.

Identify barriers and resources to help you overcome your barriers.

Revisit and revise your action plan as conditions change.

It is this last step that is often missed and causes individuals to drift. When conditions change, individuals don't take stock of the impact.

Leaders have many specific methods for evaluating their progress, from measures of organizational performance to formal assessments such as multirater feedback on their performance to seeking informal feedback from colleagues. What's important is developing a systematic monitoring and evaluation plan so that you have data, qualitative or quantitative, to help you understand what is going well or not so well. With data, you will be in a good position to make midcourse corrections.

Discovering the leader in you often blends difficult lessons and astonishing serendipity. There is no single path toward choosing a leadership that is right for you and for the people with whom you work. There is no one starting point, no finish line, no starting gun except the one you fire yourself. Successful leadership is a lifelong task of perpetual self-examination. During the process of self-discovery, concepts merge and shift as ideas about one issue spark ideas about others. Rewards and tasks change in relation to their contexts, and your own goals change over time. Each change demands a different mix of a leader's resources. You will always experience moments of drift or uncertainty. Our hope is that in those moments when you find yourself drifting, you will hear a call to reengage in the self-discovery process that can help you get back on track and discover the leader in you. From working with many leaders from all walks of society, we know that when you are in touch with your own vision, values, perspectives, and roles, you will find a rewarding leadership path.

Who are you? Who do you want to be? Where does leadership fit in your life? How would you like the story of your life to be written and its impact measured? If you carefully consider these questions, you will discover the leader in you. With the help of peers, mentors, coaches, and honest feedback, you can develop your leadership capacity with focus, guidance, and encouragement. Stay conscious of where you want to go. Keep moving, keep acting, and keep making conscious choices about where, when, how, and why you lead. And don't forget to enjoy your journey.