Assorted ebony carvings displayed in market gift shop, Serengeti

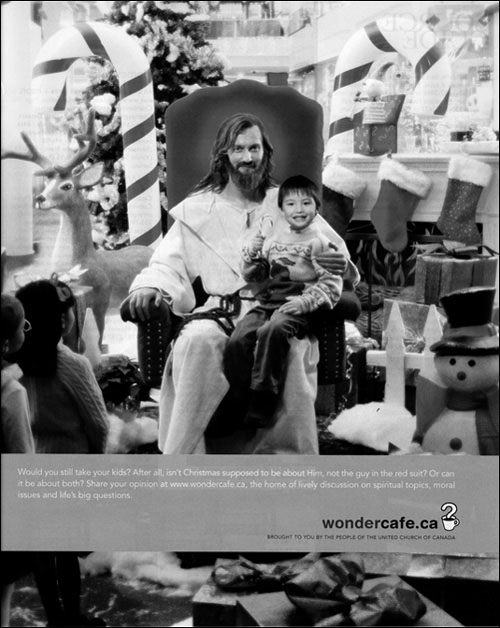

The patron saint of seasonal overconsumption has replaced the spiritual focus of Christmas with a festival of marketing, materialism, the accompanying waste... and stress of compliance

THE MOST UNDERSTOOD WORD, no matter where you go in the world, is OK. The second most understood word is Coke.[49] And 1.2 billion times a day, someone reaches for one.[50]

As intended by The Coca-Cola Company’s first president, Asa Griggs Candler,[51] we find the world’s most-recognized product within easy reach all over the globe. Coca-Cola is famous for a string of marketing firsts. Its creative team reinvented a Christian saint as a North American marketing mascot, and were the first to use pictures of women to systematically sell stuff on a massive scale.

On the streets of my hometown of Ottawa, the six-foot, backlit, all-weather, refrigerated billboards we call Coke machines have become commonplace. I am told by a manager at our local bottler that they operate at a loss as often as at a profit. These drink dispensers beckon from the sidewalks outside our corner stores in the summer heat, while our province suffers from rotating power brownouts.

As in most of Earth’s urban spaces, advertising is taking over the streets of my hometown

Other entrepreneurs have learned from Coke: A few years ago, a company offered to put recycling bins and park benches around Canada’s capital, at no cost to our city. The cash-strapped municipal government embraced the idea. Now we have advertising shaped into thin recycling bins all over town, or posing as garbage cans, each with a park bench attached. One such recycling station is planted on a traffic island where one must cross traffic on foot (or toss your recyclables from a moving car) to use it. The view when seated on many of the benches is four to six lanes of cars and trucks, while ads for products such as soft drinks are in plain view when sitting gridlocked in traffic.

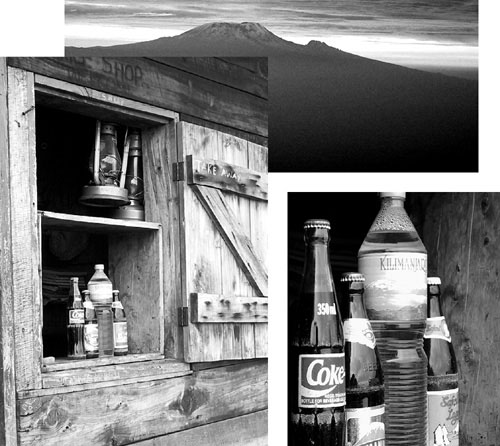

Coke has gone far further. The most remote journey I’ve ever taken was mountain trekking high above Tanzania. At the last outpost en route to the 4,600-meter peak, after two days of climbing and camping with fellow travelers Paul and Spice,[52] I discovered that someone had soldiered ahead to ensure I could exchange 10,000 Tanzanian shillings for “the pause that refreshes!”

Refreshments for sale at Saddle Hut, altitude 3,570 meters. The Kilimanjaro water brand is also owned by The Coca-Cola Company.[53]

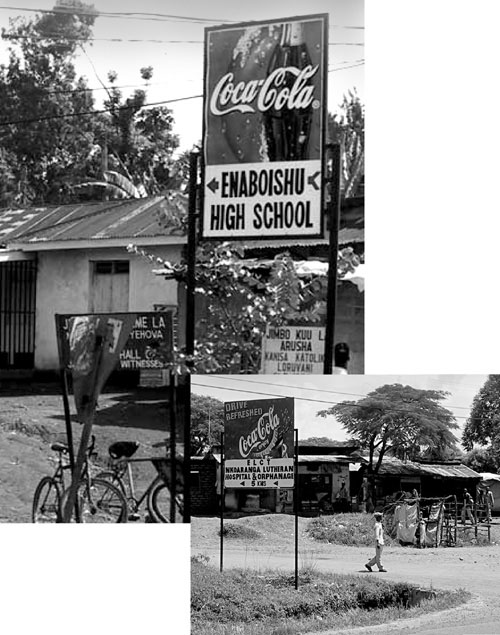

I thought this would be the extent of Coke’s admirable branding reach. Fatigued and exhilarated after making our descent, we headed overland toward the airport in Arusha, Tanzania’s second-largest city. Crossing the countryside, we saw respected schools, orphanages, and hospitals, all branded with Coke signs.

Carbonated schools, hospitals, and orphanages

Worse yet, every village on the road to Arusha was branded with soft drink logos, as if they were North American corner stores. Later that week, Amyn Bapoo, the Aga Khan Foundation’s director in Tanzania, explained to me over dinner that the annual fee to brand a village was only around $200. The villages are very proud of these brands of legitimacy; they aren’t on the map without one.

Official signage, Meserani, Tanzania

Coke’s coverage didn’t stop with villages and schools: along the side of the Tanzania’s main highways, official milestones show the distance to major cities. But each milestone is also an ad: permanent cement markers sunk deep in the African earth, branded with the Coca-Cola logo.

Offical government highway distance marker to Arusha, Tanzania’s second-largest city

expro

If that wasn’t enough to convince me of Coca-Cola’s branding conquest of Tanzania, arriving on Tanzania’s island of Zanzibar added more fizz. I discovered this wonderful ancient town of mystery, scent, and enchantment now brandishing Coke ads as the official street signs on every corner.

priation

During the 1990s, while Tanzania was challenged with disease, corruption, and poverty,[54] Coca-Cola offered to take care of their road signage and, despite the occa-sional Pepsi sign, turned Tanzania into a Coke country.

It’s masterful branding. There is much marketing savvy to learn from Coca-Cola’s advertising quest to become the most recognized product brand on Earth, as well as its Santa Claus parade of marketing firsts. Ingenious. Clever. But wise?

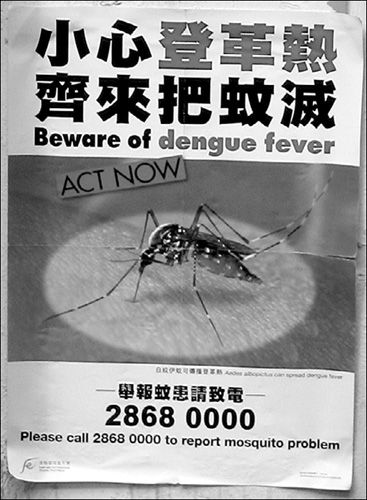

Tanzania, a country of 40 million,[55] has epidemic malaria, which either kills or debilitates those who suffer from it. With approximately 16 million cases annually, 80,000 children under the age of five die each year.[56]

Coke adds life in Zanzibar

Consider that in some parts of Africa, Coca-Cola is considered medicinal.[57] And on the desperately poor Tanzanian streets,[58] the price of a bottle of Coke is about the same as the price of an anti-malaria pill. While Coke is the best selling drink on the continent, a million Africans die each year of malaria.[59]

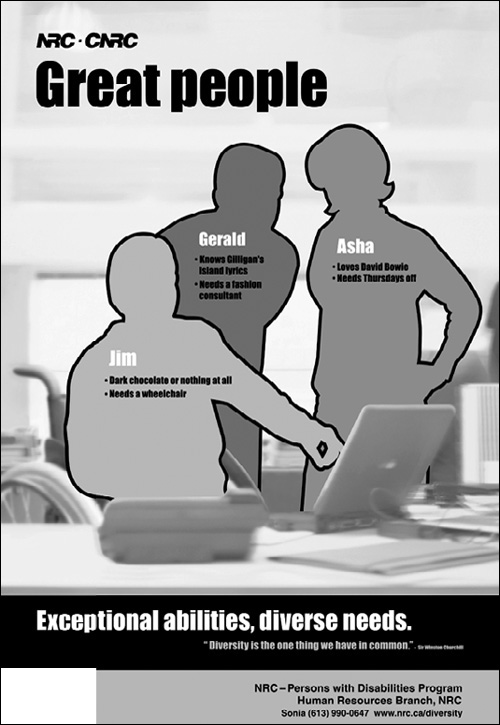

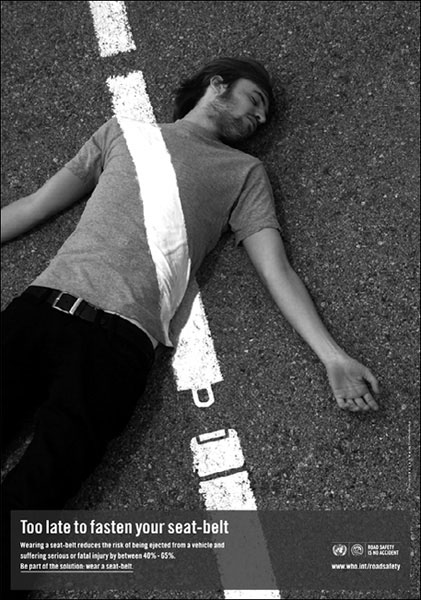

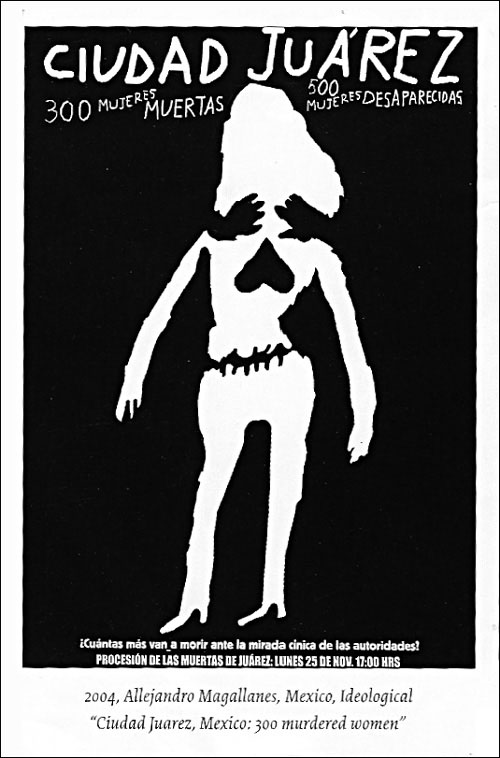

I am not suggesting that the West should not share with the Developing World. However we have many far better things to share than our dependence on carbonated caffeine. It’s an impressive feat to convince Mexicans to drink 487 bottles of Coke a person each year.[60] But rather than sharing our cycles of style, consumption, and chemical addictions, designers can use their professional power, persuasive skills, and wisdom to help distribute ideas that the world really needs: health information, conflict resolution, tolerance, technology, freedom of the press, freedom of speech, human rights, democracy... as well as to share the antidote for the buying and spending virus for which all have not yet built up resistance.

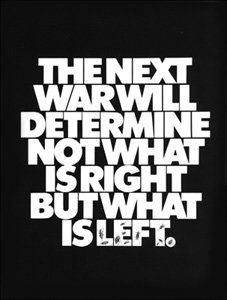

Since I was first inspired by Herb Lubalin’s application of typography to socially just causes, I have believed in the power of design to create awareness for the public good

Imagine what would be possible if The Coca-Cola Company’s uncommonly efficient distribution system in Africa could be harnessed to deliver health information, medicine, and condoms, in addition to caffeinated sugar water.

Alfred Nobel invented dynamite. Albert Einstein brought to the attention of President Roosevelt the potential of the atomic bomb.[61] Both were brilliant men who probably died with heavy hearts. If they were with us today, I believe they would tell us “Be very careful with what you create.”

In a well-designed future, it will be the message crafters, the product designers, and the experts in transporting ideas and artifacts across great distances and generations who may hold the greatest responsibility. We all have a duty to make sure that the inventions we embrace and enhance by design are not just clever but also wise; that we don’t just create intriguing, marketable stuff, but that our creations are aligned with a sustainable future for human cultures and civilization as a whole.

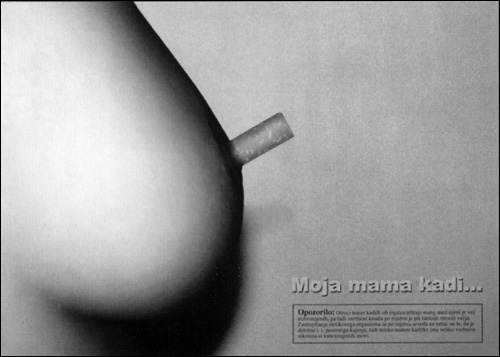

Translation: My mother smokes...

Though sharing democracy is something North Americans often lay claim to, we erode our democratic ideals when we allow our own shared spaces to become just more marketing real estate for a passing multinational corporation’s marketing plan. Something precious is lost: As we corrupt common spaces, we corrupt our common mind. Ubiquitous marketing doesn’t just cost a slice of our mindshare: it also compromises the root social-democratic concept that we are all entitled to equality, though we may differ in what we own or consume.

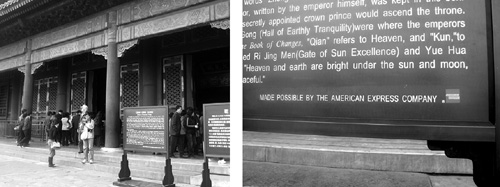

Beijing’s Forbidden City, now brought to you by American Express

Coke is working hard to make sure you can’t visit the Great Wall of China without seeing a Coke sign

In 1960, President John F. Kennedy gave his nomination speech at the Democratic National Convention within the storied Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, a structure named in memory of veterans of the First World War. In 2008, President Barack Obama’s nominating convention took place in a building called Pepsi Center, and he gave his acceptance speech from Invesco Field, named after a Georgia-based investment firm.

Before the First World War, the only major-league sports venue in North America linked to a brand was Chicago’s Wrigley Field (the chewing gum magnate owned the Cubs at the time). The next corporate branding of a sports stadium didn’t appear until 1953 on St. Louis’s Busch Stadium: the local Busch brewery family both owned the team and championed the construction.

The world’s most famous sports brand appeased fan outrage with a compromise: in 2009, they plan to cross the street to the new “Yankee Stadium in [your name here] Park”

But in 1988, the historic Los Angeles Forum was renamed Great Western Forum with cold insurance company cash. Today, 60 percent of major-league-baseball stadia have sold their identities.[62] It’s a slippery slope: In 1993, Disney named the Anaheim Mighty Ducks hockey franchise to promote a family film – what would Lord Stanley say? In Europe, it’s now commonplace for the largest words sported on football (soccer) jerseys to be corporate names.

It seems like pretty easy money, so why not run with it? Because it’s not actually free. The cost is what economists call an externality, a cost borne by a third party beyond the direct participants in the transaction. In this case, it costs local population a loss of culture and history. Local culture is traded for homogeneity, while tax relief funds the salaries of superbrand athletes. This externality of branding buildings may seem subtle because we’re used to it, so let’s consider some fresher scenarios.

Would it cost you any peace of mind if, the next time you strapped into an airline seat, you looked up to discover the inside of the airplane had as many ads as a city bus? (Just in the past few years, we already see advertising seeping into video screens at every seat.) Would it be okay with you if the handle of every public drinking fountain had an ad encouraging you to down a Pepsi instead? What if every car park in your downtown banded together to sell their airspace by pimping their brands to the highest bidder: Exxon Parking? Priceline Parking? Perhaps some entrepreneur should simply start a clothing line branded with a blue sans serif P.

How did we convince most of the world to use the letter P for parking, no matter the local language? It’s certainly an uninspired piece of icon design. And how would you feel if there were symbols in a language foreign to you all over your town? I’m surprised it’s even legal in Québec, considering that province’s extreme language laws: “parking” en français begins with an S.

Many American states hold easy-to-leverage brands (think California raisins or Florida oranges), but how about the less-famous members of the union? If the aboriginal cachet is no longer pulling traffic for “North Dakota,” why not just rename the state, or even trade the right to brand the entire territory to the highest corporate bidder? Imagine your new license plate from the Great State of Northwest Airlines, just a short commute from the Great State of Southwest Airlines.

Instead, in our states, our cities, and our countries, we can choose to retain the dignity and quality of our public spaces. The State of Vermont banned all billboards in 1968, in an effort to keep the Green Mountain State visibly so. It isn’t perfect: since “rolling stock” (moving vehicles) is exempt from the law, sometimes marketers still park trucks as advertisements. Ted Riehle, hero of the “Billboard Law,” died on New Year’s Eve, just missing the 40th anniversary year of his ongoing legacy. Alaska, Maine, and Hawaii have since followed Vermont’s example.

The standard set by Vermont’s sign law has been adopted to some degree in my province. We’re getting there...

2008: Zero storey advertising in São Paolo

In January 2008, I witnessed the remarkable outcome of an inspiring change along the skyline of sprawling São Paolo, Brazil. The world’s fourth largest metropolis used to have approximately 13,000 billboards, layered so thick that it inspired the extreme advertising portrayed in Terry Gilliam’s 1985 film Brazil. In 2007, São Paolo completely outlawed billboard advertising.[63] Knocking down arguments that loss of lighting from outdoor advertising would make the streets less safe at night (imagine!), Brazil’s largest city banned all billboards on public spaces (including the “rolling stock” – the sides of buses and taxis). This required the removal of thousands of ads by the deadline. The result: a 70 percent approval rating from the citizens.[64]

Ruth Klotzel, a member of Associação dos Designers Gráficos, which led the coalition to demand the law, told me that “the change evokes childhood memories: playing on the streets, cars and houses left unlocked, when no children were killed by random violence, where we did not feel the need for the fancy clothes and TV sets, and more than one watch. The transparent skyline reveals our history (both kind and brutal). We no longer abdicate our personality to private interests. We have reclaimed our space and our past, and rescued our dignity.”

But the larger question is this: What powerful force motivated the erection of 13,000 Portuguese billboards – mostly brand advertising – in the first place? The pollution of our physical environ-ment is rooted in the pollution of our mental environment.