“Designers: don’t work for companies that want you to lie for them.” | ||

| --TIBOR KALMAN (1949–1999) | ||

When I ask most people what they think of the design of the Coca-Cola wordmark, they say “Great logo!” However, if you look at it as if you’ve never seen it before – as a piece of typography it is awkward to read, and crudely lettered by the inventor’s bookkeeper in a Spencerian typestyle we now usually reserve for schmaltzy wedding invitations.

No, the equity and charm of the Coca-Cola mark as the world’s most recognized consumer product brand is not in its graphic design,[65] but rather in its history of consistent and incessant repetition. Though you’ve seen it thousands of times, you’ll never see it in green, nor in the wrong typeface. And though this page is black and white, you can easily close your eyes and visualize Coca-Cola red. Even in the dark, you can recognize the shape of a Coke bottle by feel. For this, The Coca-Cola Company is to be congratulated.

The corporation stands up as relatively noble when examined under the bright retail lights: the Coke brand only appears on its cola (it doesn’t even appear on other soft drinks that The Coca-Cola Company produces) so the word “Coke” continues to add value to the specific product that made it famous. In stark contrast, companies like Nautica, Tommy Hilfiger, and Nike don’t actually manufacture any-thing at all: they just brand, often recklessly so.

By the time I set up my typography studio, the art of branding had undergone a transformation. No longer just a product enhancement, branding became the commodity. The brand name itself is for sale as a representation of an ideal, a lifestyle, a philosophy. Prior to the 1990s, I could walk into a sporting goods store looking for my next pair of basketball shorts and find all my choices in one part of the store. Today I must travel from the Adidas substore to the Nike substore to the Reebok substore, as some far-off coven of “brand managers” crosstrains me to go brand shopping rather than shorts shopping.

“I don’t love it, but it’ll grow on me.” | ||

| --PHIL KNIGHTAfter paying $35 for the original Nike swoosh from designer Carolyn Davidson | ||

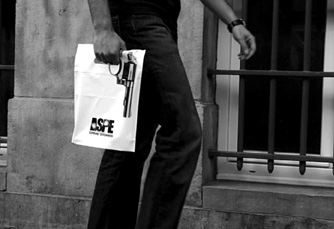

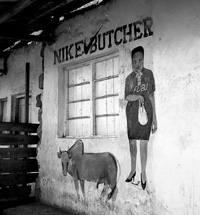

“Nike” butcher shop in Meseranti, Tanzania

“Nike” yarmulke, Ottawa, Canada

Politicians try to gain name recognition by littering our street corners during elections with signs printed only with their names. They know how much humans prefer the familiar.

We know that 60 percent of consumers prefer the comfort and security of a national brand over a no-name product or service,[66] and that preference extends to all products sold under that brand. Try on the example of Nike baseball caps. Nike made its reputation by delivering quality shoes and built a customer base who trusted its brand. So when Nike chooses to sell baseball caps, the same group of loyal customers is ready to consume such hats because they believe that Nike would only make great products. Then Nike adds a huge Nike logo on the front of the cap. Now consumers have another reason to buy the product: they can publicly proclaim their membership in the Nike club and align themselves with a reputation of quality and style. Thus, a $4 hat becomes a $19.95 hat (plus a free walking billboard for Nike) even though Nike is not an innovator in the hat-making industry.

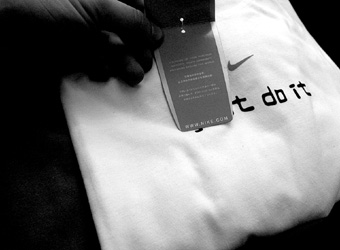

Choosing “Nike” product in a six-floor superstore of often-counterfeit merchandise. The near-perfect label reads: “A poreion of your purchase supports youth community...”

Taking advantage of the trust people naturally place in a familiar name leads many firms to put their names on products they don’t actually make.

Chanel, known for classic design of dresses, takes a $5 pair of sunglasses, adds their name, and increases the retail price over 40-fold: a hefty and quick profit. Trading on its good name worked for perfume, so why not eyewear?

Hugo Boss is in on the eyewear profits too. He knew how to produce startling high-end menswear (including the masterfully intimidating SS uniforms designed with graphic designer Walter Heck, and the creation of the Hitler Youth’s brown shirts[67]), but perhaps comes up short on optics.

I doubt Nautica has vision experts on staff either, but the company can see the potential for a quick buck.

So why are the big brands shocked when people are happy to discover they can just buy the symbol after all? Companies who brand indiscriminately compromise their brand equity by diluting the legitimate links to quality that their brand’s legitimate value was built upon.[68]

Adbusters magazine founder Kalle Lasn claims that most North Americans can only identify 10 plants, but can recognize 1,000 corporate brands.[69] I am embarrassed to say that the birds I know best are blue jays, cardinals, and orioles, having grown up a fan of major-league baseball.[70] The average American encounters over 3,000 promotional visual messages each day (up from 560 in 1971).[71]

“Logos have become the closest thing we have to an international language, recognized and understood in many more places than English.” | ||

| --NAOMI KLEIN | ||

Can you name the brands?

In 2002, I showed this array of logo fragments to an audience of designers in Amman, Jordan. Each logo has had its color removed; each only shows a small part of the symbol. Even before I’d finished explaining what I’ve just told you, audience members correctly called out the brand names represented by 17 of the 18 logos.

The one that amazes me most is the FedEx logo. The fragment is simply the letters “Fe,” in one of the world’s most common typefaces. Does this mean that every time a sentence begins with “Feel” or “Feminine” or “Ferret” in a similar sans serif font, we are subconsciously reminded of what we must do if our package absolutely, positively, must get there overnight?

Ultimately, consumers pay the cost of all this advertising. The syrup in a bottle of Coke costs the bottler one-twentieth of a cent. The estimated average cost of successfully launching a brand in the U.S. is $30 million.[73] Meanwhile, growth in global ad spending outpaces the growth of the world economy by one-third.[74]

How much is space in our brains worth? Of course our brains are invaluable: perhaps the most fascinating, precious things in the universe. But in the same way that insurance actuaries must assign a cold hard cash value to a human life, can we quantify the value of a cubbyhole in the human brain? An event in the 1990s makes it possible...

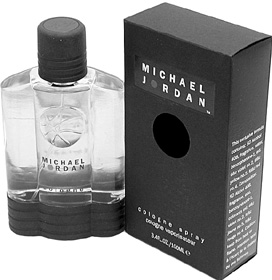

In 1995, Michael Jordan wasn’t playing basketball. Michael, the world’s most successful superbrand, had decided to retire from the sport, after leading the Chicago Bulls to three championships in a row, to pursue his boyhood dream of becoming a baseball major-leaguer. It didn’t pan out. In the 11 days between when the rumors began and Michael Jordan press-conferenced his return to basketball, the total market capitalization (total shares multiplied by the price for one share) of Michael’s top five corporate endorsers (McDonald’s, Sara Lee, Nike, General Mills, and Quaker) rose $3.8 billion.[75] That’s the perceived worth of us all knowing of the change in Michael Jordan’s career: over 50 cents for each human being on Earth.

You too can smell like a basketball player

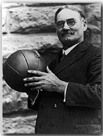

James Naismith, inventor of basketball,[76] who grew up less than 50 kilometers from my home, would have become a multimillionaire if he’d had an agent

Where is that money? It’s not sitting in a bank somewhere. It represents mindshare: shares of our minds. The stock market assigned a value of 50 cents for each brain that knew Michael was slam-dunking again above a wooden stadium floor in Chicago.

Fast-forward to August 2008, when we witnessed China spending more than $40 billion on the Olympics, dramatically injecting the minds of television viewers worldwide with an impressively repositioned brand of the world’s third-largest purchasing power. For the bargain price of around $6 a head, this form of invasion is certainly cheaper than conventional warfare... perhaps it now is conventional warfare.

The shift for the China brand for me occurred in 2006, when my friend Professor Xiao Yong toured me through a tucked-away section of China’s top design school. There, his team of professors and students was diligently crafting the entire Beijing 2008 look: banners, medals, wayfinding signage... I was impressed to see students perfecting an identity system that could best the work of a top global design agency in London or Los Angeles. I found myself correcting negative bias I had been taught long ago against the Chinese system of governance.

Students working on the graphics for the Beijing Olympics at CAFA, 2006

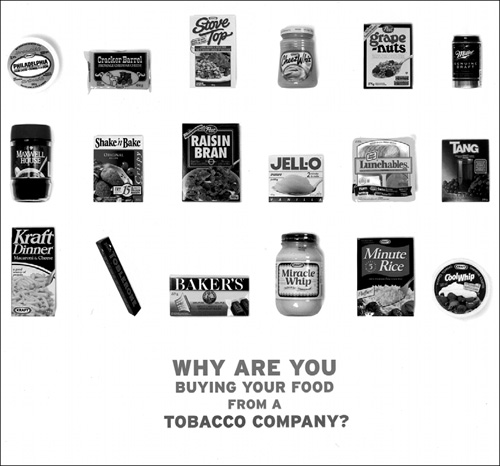

In 1988, Philip Morris, desperate to further diversify its tobacco roots, bought Kraft Foods, what was then the largest non-oil acquisition in U.S. history. They paid more than $12.9 billion, three times its market valuation, due to its brand equity. The value attributed to branding changed forever.[77]

After a talk on design ethics in Oslo, I was hunting for my favorite Scandinavian snack, salt licorice. Jan Neste, president of Grafill (the Norwegian Association of Graphic Designers and Illustrators), proudly offered me a Freia Melkesjokolade chocolate bar instead. We turned over the famous yellow package and discovered that Freia was now owned by Kraft: Norway’s most beloved candy brand had been bought by an American tobacco company.

Today, brand valuation falls within U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) and there is now an ISO committee to establish an international standard on brand valuation.

Philip Morris combined Kraft with General Foods, then added Nabisco in 2000

Remember what I said about Michael Jordan and 50 cents a brain? Since only a fraction of all 6.7 billion humans are in Michael’s target audience, the message value for each target brain is actually much larger. Or is it? Would it be defensible to include the entire world population in this calculation? The reach of marketing messages has grown dramatically since 1995. In 2003, the NBA sold over $600 million in merchandise outside the U.S. (that doesn’t include broadcasting revenue).[78] The Internet represents the quickest proliferation of visual messages in the history of the planet. According to business guru Tom Peters, it took 37 years for radio to penetrate 15 million homes in the U.S., while the Web reached that point within four years.

Like many, I assumed the Internet would increase open competition because it lowered the cost of entering the market. And while it has created what Wired’s Chris Anderson calls a “long tail,” where virtual bookshelves can hold far more titles than brick-and-mortars, there doesn’t appear to be any less market concentration at the top.

Indeed our current era is defined by falling tele-communications costs, making it easier to promote concentration of a particular brand. The American JBANetwork e-mail service offers to send 10 million e-mails for $8,000, at a rate of more than 100,000 messages an hour. Our ability to transmit information and products to new markets has never been less expensive or more immediate. Further, the sophistication of how messages are used to influence behavior is ever-increasing, as research into the mechanics of neurology and human behavior flourishes.

“Whether we will acquire the understanding and wisdom to come to grips with the scientific revelations of the 20th century will be the most profound challenge of the 21st.” | ||

| --CARL SAGAN (1934–1996) | ||

The more that the Internet makes us all broad-casters, all consumers, all potential makers of things explosive, the more we need the guidance of our parents, our teachers... our principles.

The globalization of overconsumption and lying is obviously counterproductive. Whether you are a fan of globalization or not, it is an unstoppable force. However, globalization can enable an emerging nation to progress in only 10 years to the same place that took 200 years for the United States. Such rapid development carries a correspondingly serious risk to cultural diversity. One way to protect that culture is by expressing it within principled and ethical professional behavior: such expression can help inoculate a culture from the downside of globalization’s velocity.

Interactive advertising adds another layer of impulsive, instant gratification: in this ad you can drag the vertical bar left and right

“Globalization will be sustainable if each of us manages the filters needed to protect our cultures and environments, while getting the best of everyone else’s...? rather than a homogenization of them.” | ||

| --THOMAS FRIEDMAN | ||