“What is wrong is a style of life which is presented to be better, when it is directed towards having rather than being. | ||

| --POPE JOHN PAUL II (1920-2005) | ||

TO PARAPHRASE STEVE MANN, the eye is the largest bandwidth pipe into the human brain, and graphic designers spend their days designing what goes in.[79] When you leverage that power in order to deceive people, then those cleverly crafted messages and images become lies. We have a responsibility to not exploit this power.

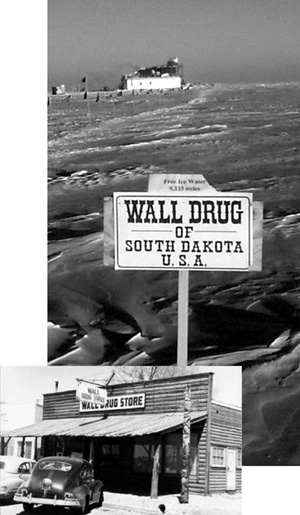

Are branding and advertising, by their very natures, misleading? Not at all. Most advertising is truthful. I love clever branding and advertising. Great advertising can drive down prices, support healthy competition, promote innovation, and even entertain. Advertising is part of human culture and has been helping people get information they can use to choose products, ideas, and actions ever since the first “Cave For Rent” sign went up. I’m even oddly nostalgically charmed in discovering yet another Wall Drug sign. The drug store in Wall, South Dakota, spends around $400,000 a year on billboards that run for thousands of miles on American interstates.

Top: Wall Drug sign at the South Pole: free ice water, just 9,333 miles Bottom: Wall Drug Store, 1949

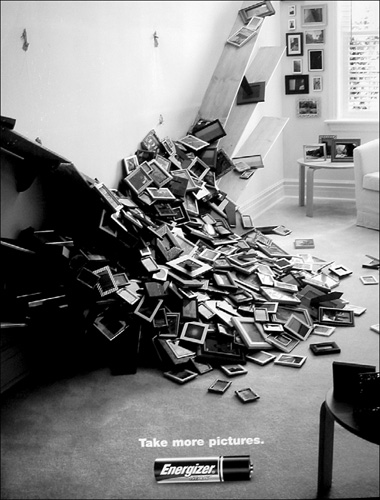

Beirut’s Walid Azzi presented this clever ad as an example of how to promote a sexy product using imagery in a sophisticated way. As publisher of ArabAd, the Arab world’s largest industry journal, he knows his audience: we were in a conference hall in Bahrain, where culture forbids exploitative images of women.

A picture can speak louder than words, and thoughts completed by the viewer will often linger longer than those that are spelled out

Certification of the International Wool Secretariat, designed by Francesco Seraglio in 1964

The Morton Salt girl

800 to 3,000 percent markup

There are wonderful examples of effective and positive branding of worthwhile organizations, products, and ideas. Since 1863, international brands such as the Red Cross have served society: everywhere you go, people know they can run to such humanitarian symbols when they need help, food, or emergency shelter.

The Woolmark is a very useful brand: it tells me that the jacket I’m thinking to buy is made of wool, and guaranteed to a certain level of quality.

Morton Salt’s delightfully clever slogan distinguishes its product as the one that will pour even when humidity is high. Clear, helpful, and memorable.[80]

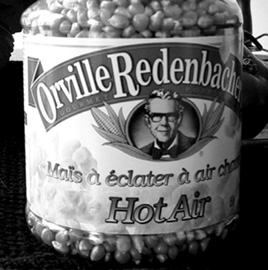

Orville Redenbacher took the commodity of popping corn, which costs little to produce, and found success in the huge gap between the cost of the product and the perceived value in making it pop slightly larger. I have no qualms with him figuring out a way to make more than a 1000 percent markup while encouraging us all to consume more fiber. But was Orville dreamed up by some clever ad agency? No: Orville really existed. Born in Indiana in 1907, he grew his first corn at 12 and it put him through college. Later he developed light and fluffy hybrids, before peacefully popping off in his Jacuzzi in 1995.

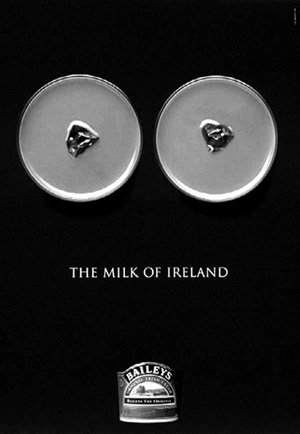

Now consider this bottle of the world’s top-selling liquor.[81] How old do you figure the Baileys Original Irish Cream recipe is? The Celtic imagery of the label gives the sense of a tradition going back perhaps hundreds of years.

800 to 3,000 percent markup

Today, the Baileys myth is sold in over 130 countries

In truth, the Baileys recipe was invented in a London boardroom in 1974, when a glut on the Irish milk market ran up against the puzzle of how to get young women to drink 80-proof whiskey.[82] The Baileys “family name” was taken from a hotel visible from the office window. Today, the Baileys myth is sold in over 130 countries. The milk used for Baileys accounts for over four percent of Ireland’s total milk production.

Marketers often seek ways of engaging their audiences on a deeply subconscious level, by linking invented images with trusted reference points in their audience’s memories.

How powerful is this kind of activity? Bruce Brown, a brilliant Scottish design professor, currently pro-vice chancellor at University of Brighton, taught me to think of graphic design as “designing memories.”[83] Newsprint may only carry an advertisement for 24 hours before it lands in the recycling bin; however, if the designer has succeeded, the images and ideas conveyed linger in our minds, lurking, waiting to leap into our consciousness when the correct mix of desire and opportunity intersect.

As psychologist Howard Gardner points out, the basic unit of human thought is the symbol. Of all the animals, humans are the symbol-makers. Many symbols (and remember that words are also symbols) are designed to deceive as well as to inform. Symbols are the building blocks of reason and of memory, so it is unethical to intentionally insert misleading symbols... and cruel, since our memories retain such symbols long past the point that we have classified their intended meanings as unreasonable. It is also well understood that people expose themselves selectively to facts that don’t support their first impressions.

Our ability to recognize and trust symbols can be a matter of life and death – ask any color-blind driver approaching a red traffic light. And we are naturally inclined to trust all images, because until very recently in the long history of animals, the only untrustable images were in puddles and mirages.

So how persistent are the memories created by brand advertising? Here’s a powerful example of the extent to which images can linger. In 1981, a false rumor surfaced linking Procter & Gamble’s trademark logo to Satanism. After four years of frustration trying to quell the rumor, the corporation removed the symbol from all packaging. Five years further along, in 1990, Procter & Gamble was still receiving 350 calls a day asking about the logo’s demonic past.[84]

Procter & Gamble logo, pre-1985

Here’s a more unsettling example of the persistence and influence of manufactured memories:

Tragically, the Nazi party and its use of the swastika represents perhaps the most effective branding campaign of the 20th century.

Hitler’s party repurposed this famous symbol. The swastika has been used for thousands of years by various cultures. Sadly, none of them chose to trademark it.

Though this simple arrangement of the two crossed squiggles represents a regime that met its demise in the 1940s, its ability to make many in Western culture wince persists today. A symbol that meant little in the West a hundred years ago was permanently infused with much meaning by an intentional exercise in identity branding and association.

Storefront, Beijing, China

So what is the potential power, destructive or otherwise, of the memorized symbols and the ideas associated with them that are left behind in people’s brains? The 20th century was driven by this persuasiveness of ideas, which resulted in the quickest, most widespread torrent of murder and social upheaval in the history of civilization.[85]

How many died in the past 100 years due to buildings collapsing? Compare that to the tens of millions murdered in the same period due to the carefully orchestrated propagation and perpetuation of evil lies.

Today, in the Developed World, we insist that a certified architect approve plans for all commercial buildings. This is wise: as a society, we recognize the potential danger if buildings like the one you may be in right now falls down. I believe the time will soon come when our civilization matures enough to recognize that visual communicators manufacture misleading memories and those visual lies can be just as dangerous as melted steel.

Except the most powerful, largest lying machines in the world today are not the Nazis or any other political party. Nor is it Al-Qaeda.

In Canada, you only need to take 0.5 percent of the beer market to have a successful brand.[86] You can choose to design packaging that repels most, yet as long as it appeals to a niche it will succeed. So what stops a designer from helping a microbrewery put a swastika on a beer label, knowing that they could sell over 0.5 percent on shock value alone? (Clearly the example is extreme, however our globalized wine stores now sell imported labels with names such as “Fat Bastard” and “Cat’s Pee,” which use a calmer version of the same mechanism.)

Whether the lingering visual memories are the sexuality of Internet pornography or the idealized images of beauty that convince Colombian 14-year-old girls to ask for breast implant surgery for their quinceaños (the traditional Catholic 15th birthday coming-of-age party)[87] – whether it’s Brazilian peasant women in Amazonia buying Avon cosmetics rather than food[88] or the violence of Saturday morning cartoons – the design of memorable imagery is powerful weaponry.

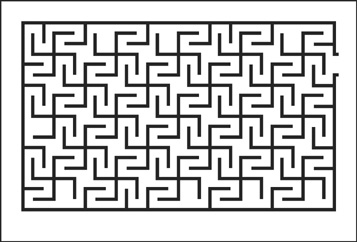

The same symbolism can be used as a force of good: swastikas in this ad by anti-Nazi group Exit attract neo-Nazi youth to Exit’s strategy that helps European kids out of a maze of hate

The answer lies in where we will draw the line of what is acceptable, and how soon. If the market is left to draw the line, then the integrity of the design profession will also likely be called into question (and rightfully so). Better that the profession establishes a higher standard than what prevailing social morality will tolerate.

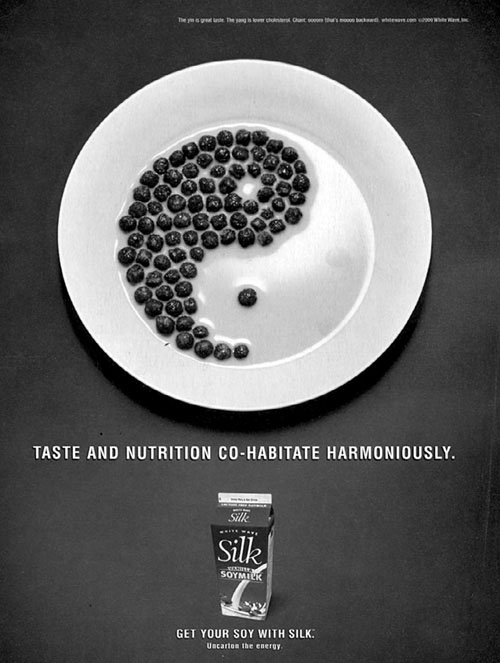

Who gives permission to a soy milk advertiser to use one of the most sacred symbols of Eastern religion to have us reverse our breakfast habits? There is an irony when large corporations, typically the biggest fans of trademark law, rip off the meaning of a symbol that has been built up over thousands of years of cultural activity.

I wonder if it would be different if a Christian cross was used to sell cereal. How long until someone recognizes the power and potential leverage of that symbol? Perhaps someone already has.

Selling soy milk by selling out the sacred

In the midst of the riot (and more than 100 deaths) around the publishing of cartoons depicting the prophet Muhammad in a Danish newspaper, I was asked by a Canadian reporter if I thought Jyllands-Posten had the right to publish those drawings. My response was that they certainly did.[89] But I added this: just because we can do something, doesn’t mean we should. And that is where professional judgment is needed. “Do no harm” is an excellent signpost.

McDonald’s: “Vigorous beef makes you more vigorous”

Mohawk gasoline station sign, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan

If you have been to Western Canada, you’ve likely seen signposts like this one for the Mohawk gasoline station so often that it probably wouldn’t register with you as a caricature of an aboriginal. Would it be different if it proclaimed Jew Gasoline with a clever logo of an ultra-orthodox Jew in a tall black hat and curly sidelocks?

Mohawks are one of many proud First Nations in North America, and though I am certain no one meant any harm when they chose the Mohawk name for a chain of gas stations, any more than intended when sports franchise owners named the Atlanta Braves or the Washington Redskins, it should certainly not be considered acceptable branding.

The transfer of pride from tribe to product in cars named Pontiac is so complete, few recall the roots of this brand. We often isolate what we admire in a group, without really understanding much about them. This unfortunately strengthens myths, while distancing us from the reality. The gap in health and living standards for Canada’s aboriginal peoples compared to other Canadians has consistently widened over the past 50 years.[90] How do we remain so desensitized? Do these simple, shiny images help us push away a truer picture that is more messy to grapple with?

And if it is so with a minority, would you believe me if I told you we are doing a similar injustice to half our population?

“Possible ≠ desirable” | ||

| --TERRY IRWIN | ||