A documentary begins with an idea and the desire to communicate it to an audience. In this it is little different from the starting point of a fiction film. But the idea which begins a documentary is usually subtly different from the starting point of a fiction. Both arise from the real world—else there would be no contact point with the audience. But where the fiction film-maker turns inward to explore his or her internal world, putting imagined characters into an invented situation and following the consequences, the documentarist devotes him- or herself to the external world, the real world as we are forced to call it.

Both forms tell stories with which their creators hope to say something about life, the world and the human condition, but the documentary film-maker chooses a medium which, while less costly and easier to realize, is harder to excel in. Though there are vastly more workmanlike documentaries made than feature films, and many more good ones, great documentaries are as rare as, perhaps rarer than, great feature films. Both forms, like all films other than animations, depend on capturing a record of events which really happened in front of the camera. Here the two media divide. The fiction film-maker commands a world into existence to show to the audience. The documentarist must extract a world from the reality of life.

Believability is one of the judgements made about fiction. The fictional story must persuade its audience that the events could really have happened, that the characters could really have existed. Everybody knows that reality is sometimes just too unlikely to be convincing. Truth may not really very often be stranger than fiction, but it is frequently much less immediately convincing. Yet the documentary comes with a guarantee, not necessarily of truth, but of being grounded in reality. A documentary’s authority depends on the explicit claim that what the film shows represents or corresponds to something in the real world. Though in fact the history of documentary is littered with examples of the faked and the phoney, the documentarist who cheats on the promise to present reality forfeits everything.

Audiences take the documentarist’s honesty for granted. However, as they have become more discriminating over the years, viewers are perfectly well aware that film-makers only show a carefully selected part of the picture—the part that suits their argument. But though partiality is accepted, inconclusiveness is not. The documentarist’s work is judged not so much on its content, but on its argument—how the content was presented. In the professional jargon: ‘does the story stand up?’

In a feature film, story is everything. If there is an overt moral pay-off or a philosophical conclusion, that is a bonus; a fiction can do without them quite well enough. The audience responds to the way the story elements are handled and brought to a conclusion. But a documentary, because it makes a claim for reality, will inevitably do more than tell a story. Since the story is taken from reality its audience cannot but come to some judgement about it.

Much fiction is intended as entertainment and teaches us little. When fiction moves us, it is because something in its imaginary world corresponds to something in our real one; it takes considerable artistry by the fiction film-maker to persuade us to make the match. First we have to put the material through a complicated mental transfer from the film world to our own. In the case of a documentary production, the relationship between what is shown on screen and the reality which it records is not as simple as it may seem, but the distance between the two is nothing like as far as it is in fiction.

What is shown on the screen in a documentary are extracts from reality, presented in different ways, chosen to point up some meaning, some pattern in the real world. It could be a pattern of events, a pattern of relationships, a pattern of personalities, a pattern of facts. It may be expressly presented as a narrative, or by description, or by explanation. The aim of the documentary is to persuade the audience to see the same pattern as the film-maker. In this, the documentarist is engaged in a task which is absolutely fundamental to human understanding.

‘Which is how we see the world,’ said the surrealist painter René Magritte, in a lecture explaining his painting La Condition Humaine. ‘We see it as being outside ourselves even though it is only a mental representation of what we experience on the inside.’1

All living creatures depend on the ability of their nervous systems, no matter how primitive, to impose order and meaning on the chaos of sensation. All are equipped with some kind of mechanism for pattern recognition. Even the simplest and most primitive living things, viruses and bacteria, are equipped to recognize, among the tohu bohu of the sub-microscopic world, the molecular patterns which spell substrate or food. More advanced creatures, including ourselves, depend on discriminating meaningful patterns from out of the apparently random signals constantly stimulating our senses. That is how we living creatures survive. But it is our brains that construct the images, not our eyes; our brains and not our ears that recreate for us the sounds we recognize; our brains not our eyes which build for us the image of friend’s face or a yellow rush-woven chair, our brains not our ears which create in our minds the sound of a busker’s violin above the traffic noise.

Discrimination begins early in life. The youngest baby is already primed to recognize the pattern of sight, sound, smell, taste and feel that means mother. Experiments have shown that such recognition even survives transmission by television. As we mature, our pattern recognition ability develops. We learn to read and write in words, sentences, paragraphs—patterns which become so tightly associated with our language that we cannot write without hearing the words inside our heads or speak the words without being affected by the way we write them. As functioning adults all our perceptions depend on the processing and matching of vast numbers of these memory patterns, the kind which lead us to recognize cousin Bill in the street from two hundred yards away by something about the way he walks.

So programmed are we to detect pattern in our environment that we almost invariably succeed—it is almost impossible not to see pattern even where there truly is none. Wherever and whenever human beings have looked up at the stars, they have seen patterns; though the patterns result from no more than chance lines of sight. But different people have seen different patterns, and the same pattern has been interpreted in many different ways. A cluster of seven points in the night sky have been seen as a Plough, as a Wain (wagon), as a Great Bear, even as a Big Dipper (ladle). Each image as valid as the next, but none expresses a real celestial relationship (Fig. 3.1).

Fig. 3.1 Seven stars can be seen as a plough, a wain, bear or a dipper.

We apply pattern recognition not only to the input of our sense organs, we automatically look for patterns in all forms of information that enter our heads, even the purely abstract. And as with the stars, it is hard but useful work to distinguish the meaningful pattern from the accidental. The scientist looks for patterns in data; scientific method is then applied to find out if the patterns mean anything. The philosopher seeks out patterns in the world and tries by intellectual argument to establish how significant they are. The politician claims to discover patterns in the realm of society and politics; though not all politicians are keen to test if their observations correspond to any real underlying structure.

It is one thing to see the pattern yourself, it is quite another to cajole someone else into seeing it too. In some cases, a person’s whole self-image and identity can be bound up in the everyday perception of, say, class struggle or God’s handiwork. To persuade the really devout to relinquish the pattern they see in the world in favour of a new one is probably impossible, short of full scale brainwashing—which is the only known technique by which a victim can be forced to abandon long held mental patterns and replace them with new, approved, ones. We all hang on to our own view of things with pretty fierce tenacity. Changing one’s perception is rather like the optical illusion in which one can switch depressions like craters on the moon from looking concave to convex: it takes some effort but once done, the impression sticks (Fig. 3.2). Patterns may at first be quite hard to make out, but once learned they are even harder to forget.

The documentary maker is a seeker and a pointer-out of patterns, often combining scientist, philosopher and politician in different measure, depending on the nature of the film. For the documentarist the patterns are sequences of events, combinations of characters, resonances in behaviour, connections between ideas. The documentary maker’s work is to find ways of showing the audience an original and meaningful way of looking at things. Whatever it is about, whether it be a history of warfare, a video diary of a trip to the seaside, a record of a space mission, a story of an office power struggle, an ecological exploration of the Serengeti, a film is its maker’s way of saying: notice the way that this relates to that and connects to yet something else.

So a documentary film is the result of sieving out from the real world those elements which best point up meaning. It is impossible to include all of them. The film’s maker must select those cues, signs and details which tell the audience most. He or she is aided by the fact that human perception depends on a wide variety of sensory sources and great redundancy of information—the same content comes through to us in many different ways, reinforcing the security of our hold on the image. It is easier to hear someone in a noisy cocktail party if one can see the person’s lips, even if we are not lip-readers; an ambiguous shadow is often resolved into a recognizable shape by its sound.

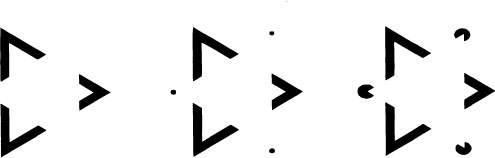

Because of this redundancy, one of the tasks of an artist in any field is to judge which clues are the most potent, the most evocative, and let go those which would merely add support or fill in unneeded detail. The task is not unlike that of the many optical illusions which depend on the brain’s ability to pick up clues and fill in the rest. In a familiar optical illusion the white triangle varies from very indistinct, to clearer when the corners are marked by dots, and even clearer yet when the corner angles are supplied (Fig. 3.4). In no case is it explicitly drawn.

Fig. 3.2 Once seen as concave or convex, the perception is hard to change.

Fig. 3.3 By screwing up the eyes or standing well back, most readers will be able to make sense of this picture.

This optical illusion suggests a role for the artist in any medium. He or she will seek out just those details which enable the audience to supply the rest from their own mental resources. The more the audience contributes to the perception, the more satisfying is the resulting image—seeming to belong to them, rather than seeming an alien view foisted onto them less than willingly. To build up a picture in someone else’s mind is to allow that person to contribute largely to it. So the search is always on to sum up as much as possible of the artist’s argument with the simplest and most economical pointers possible. Give the audience too much, and they may have the feeling that they are being got at.

Great care must be taken to ensure that the details really do contribute to the pattern rather than distract from it. In the effect first demonstrated by Harmon (Fig. 3.3), spurious and irrelevant details—the edges of the blocks of tone—interfere with the brain’s ability to make sense of the pattern. Only by screwing up the eyes or stepping well back so as to make the block edges less distinct, will most readers be readily able to make sense of the picture. This has been called the Abraham Lincon effect. How significant that so little information—hardly more than three hundred and fifty tonal squares—can generate such an immediately recognizable complex image.

Such considerations apply to artists working in all fields. A representational painter or designer depends for his or her success on providing the audience with just enough hints and clues to suggest three-dimensional form. And some cultures emphasize economy and subtlety above almost all other considerations: a Zen ideal is of a complete drawing made by a single stroke or gesture with the drawing brush. As Michael Caine has shown in his movie master classes, the art of the film actor depends largely on giving away only the most highly economical clues about the character’s internal state. The audience is so attuned to reading such signs that anything more than a hint looks like over-acting.

Fig. 3.4 The white triangle varies from indistinct, to clearer when the corners are marked by dots, and even clearer when the angles on the corners are suggested.

The documentarist too is looking for economy and subtlety in presenting his or her vision of the world. One of the most important skills in the film-maker’s repertoire is the ability to recognize which are the most significant, revealing moments, scenes, personalities, objects. And if any one such series of images can contribute pointers, clues and hints to more than one aspect of the overall pattern, then so much the better. Ambiguity is no problem. Allowing, encouraging the audience to make their own mental contribution to the film’s meaning is not to short change them but to give them an active role in making sense of the film’s world. And an activated audience is a satisfied audience, who will almost certainly ascribe to the skill of the film-maker what, in actual fact, they themselves have contributed to the meaning of the work. Sleight of hand? Maybe. But a factor on which the reputations of some of television’s greatest documentarists have been founded.

Note

1 Magritte—La Ligne de la Vie 1938