CHAPTER 9

Selling New Ideas

I never want to invent anything I can’t sell.

Thomas Edison

Sure, innovation is critical, but

it doesn’t amount to anything unless the

rest of the world does something with it.

Douglas Engelbart, inventor of the computer mouse

An innovation, by its nature, is something different. It requires getting used to. It requires a little “hand holding” to get the user “up and running.” Somebody has to help it “catch on.” And that somebody is the innovator.

Innovation has always been about selling ideas. Innovators throughout history have willingly and ably embraced the need to sell their ideas to a skeptical world.

Thomas Edison didn’t just develop direct current electricity. He trained a team of salespeople to go door-to-door demonstrating the advantages of lighting your home with electric lights. To lessen the consumer’s perceived risk, Edison promised prospective customers that if they weren’t completely satisfied, he would remove the wiring and reinstall kerosene lamps at no charge.

166Walter Chrysler was frozen out by General Motors and Ford from exhibiting his maiden car, the Chrysler Six, at the industry’s annual exhibition. Undaunted, he quickly rented the lobby of the New York hotel where most attendees would be staying and exhibited his automobile there, creating even more attention for his launch.

Selling Strategies for the Global Economy

Innovation in the era of change, competition, and complexity requires that you and your firm master a sophisticated, multifaceted set of selling skills that are needed both internally and externally to build the buy-in and get the idea happening in the real world.

Internally, this means the idea’s sponsors, led by a champion, who in turn leads a cross-functional team, are successful in getting it funded, approved, and accepted. They gain buy-in from all internal players in the organization and from suppliers, alliance partners, distributors, and channel partners, who have the power to assist or kill the idea, depending on their support. Most importantly, gaining internal buy-in means gaining continuing support from senior managers (and fellow senior managers, if you are part of senior management) in the organization to support and fund the idea and otherwise help it along.

Externally, building the buy-in means gaining acceptance for the idea in the marketplace such that it sells. Decision makers decide on it. Purchasing directors purchase. Customers buy it. It produces top- and bottom-line revenue growth.

Are you ready to perform this final act necessary for successful innovation? This chapter will help you build upon the competencies you and your firm already have in this area. But be forewarned: Far from being a mere afterthought or something that, once the idea is ready for launch, can be thrown over the wall to the sales team, selling an innovation is actually critical to the idea’s success. Developing the skills of selling ideas, both internally and externally, must be viewed as a vital part of a firm’s embedded, systematic innovation process. It must become everyone’s responsibility. It must become part of the discipline of innovation. And it must be seen as a vital part of a comprehensive approach to driving growth through innovation.

167

The Bottleneck Clogging the Pipeline, or Why Selling Ideas Is a Growing Challenge

Fast-forward to the future for just a moment and imagine your company having integrated and embedded an innovation strategy into its operating processes. Congratulations! You did it! Your company has become super-adept at organization and you can launch major innovations every couple of months.

The next question becomes: Could your customers possibly handle that rate of innovation coming at them? The probable answer: no. The innovation pipeline doesn’t do you any good if it bottlenecks at the customer end. If new products and services emerge faster than customers can absorb, you don’t get top-line growth; you get failure.

Any innovation process must necessarily concern itself with the issue of customer acceptance. How long does it take all your various customers, channel partners, gatekeepers, and end-users to integrate your new products and services? To amortize the costs? To find the time to learn how to use your new ideas? And what can you do at the beginning of the pipeline to accelerate the customer’s ability to derive value from your ideas at the end of the pipeline?

The growing reality is that there are simply too many ideas—albeit, incremental improvements and line extensions—chasing consumers with finite resources, and a finite ability or motivation to adopt them all.

Here’s why:

- The customer’s basic needs have been met. In developed countries, at least, basic problems have been solved by existing products, or so the consumer thinks. Thus, future innovations from your company will arise from seeking out unarticulated needs and will increasingly demand that you build the market for that idea because, for customers to derive benefits, behavior change on their part is required.

- Customers face overchoice. The Consumer Electronics Association estimates that more devices will have been launched from 1998 to 2003 than during the entire previous history of the industry. Kellogg’s Eggo waffles come in 16 flavors. Procter & Gamble markets 72 varieties of Pantene hair care treatments. Kimberly-Clark’s Kleenex tissue comes 168in nine varieties. S.C. Johnson’s Ziploc garbage bags offer twist, drawstring, or handle ties. The result of such a proliferation is to produce a condition in consumers commonly called overchoice, a term coined by futurist Alvin Toffl er in his 1970 book, Future Shock.

- Customers have upgrade fatigue. Computer manufacturers and software makers are “struggling to deliver meaningful-enough innovations to keep users regularly upgrading their PCs and programs,” reports the Wall Street Journal. “My people tell me there has not been a compelling reason to go to [Microsoft’s new version] for our business requirements,” one corporate purchasing official was quoted as saying. It isn’t just the computer or software industries that are affected.

- Customers resist the costs of planned obsolescence. Early adopters in the software and hardware arenas have lured customers all too often onto a cynical cycle of planned obsolescence by developers. Customers see that other industries are attempting to play the same game, and they are voting with their pocketbooks, trying to stop the game before it gets too far. Purchasing the DVD player means that your library of VHS movies is suddenly rendered obsolete, as well as your VCR. As more and more offerings are brought forth that make ever more fatuous claims, the vast middle of adopters becomes more and more skeptical by the day.

Seven Strategies for Selling New Ideas

Count on new ideas facing greater customer scrutiny and resistance, the newer and more unfamiliar they are. The days when you could build a better mousetrap and customers would beat a path to your door are over.

Given these changing realities, emphasis these days must be given to the skills and techniques of selling new ideas. Let’s look at seven strategies for selling new ideas:

Selling Strategy 1: Make everyone an idea evangelist.

Guy Kawasaki’s business card at Apple Computer said simply, “evangelist.” It was Kawasaki’s job to talk up Apple’s new products to the media and to appear at trade shows such as Comdex and Apple’s own annual gathering of its users and developers and create good feelings.

169Selling New Ideas

- Make everyone an idea evangelist.

- Focus on the customer’s mean time to payback.

- Make it safe for customers to experiment.

- Sell conceptually.

- Build markets for your products and services.

- Convert the early adopters and gatekeepers first.

- Be persistent.

Anybody who ever hopes to be effective as an innovator would do well to emulate Kawasaki’s style. The word evangelist might conjure an image of drawling preachers bringing sinners to repentance, but it is their devotion to their mission that perhaps caused those in the Innovation Movement to adopt the term, for they must gain converts. In our interviews with innovation initiative leaders in the Innovation Vanguard firms studied for this book, these leaders clearly show the need to “build the buy-in” lest the initiative fail. Innovation-adept firms not only take selling seriously, they “unleash the inner evangelist” in everyone, realizing that everything has to be sold.

- Evangelists master the art of persuasion. They know how to use the right message with the right audience at the right time. They work on communications skills and on energizing their briefings, descriptions, board reports. They join organizations like Toastmasters to improve their speaking skills. Evangelists know how to craft their messages so that people pay attention.

- Evangelists focus on benefits, not features. Benefits are what every salesperson learns to focus on, addressing the issue of “what’s in it for me?” Not how the idea will work, not its features, but what it will do for those it is planned to bring added value to. Will it create additional customer satisfaction because it brings about greater speed or convenience? Will it reduce costs without reducing customer delight? Will the idea raise employee morale or make the workplace a little more fun? Will it increase safety, aid efficiency?

- 170Evangelists use skeptical thinkers to get the bugs out of their pitch. While positive thinkers and possibility thinkers are prone to like your idea no matter how far-fetched, they can actually lead you astray. They’ll tell you that it’s a great idea regardless of the flaws. But when you seek out skeptical thinkers, you’re bound to get another perspective on your idea.

- Evangelists help others visualize new ideas. Once you’ve done your homework and have isolated the benefits, you’re ready to get feedback on your idea. Start with friends, teammates, mentors and other people whom you trust to be forthright but sympathetic.

The key thing you want to do is help them to see your vision for what could be. You want to draw a picture, create PowerPoint slides, anything that is visual and provides a common reference point other than just the talking head. The more others can feel, taste, touch, and see the idea represented, as if it’s already a reality, already operational, the greater your selling success. Effective communication is half the battle. People don’t like to admit that they “don’t get it,” that they don’t understand your idea, that it’s too complicated. But as every evangelist knows, if people don’t understand, they don’t buy. - Evangelists speak the language of the people they are selling to. How you “sell” an idea depends to a great extent to whom you’re selling it. If you’re making a pitch to senior management about an idea management funding committee, that’s a different sales job than presenting an idea to your team. It’s a different sales job if you’ve been invited to present an idea to the board of directors. Effective evangelists find out as much as they can about the thinking styles of those they are pitching. If you have a mix of people, such as marketing, sales, human resources, finance, information technology and other specializations, you’ll need to incorporate various devices to satisfy each member of the group.

Think about the personality style of the person or persons you’ll be presenting your idea to. Are they analytical, mavericks? Do they tend to be more comfortable with changing the system or perfecting it? Analytical persons need the data and numbers that make the case for your idea. If your audience is more “big picture” oriented, don’t bog them down with too many arcane details. They realize all these things have to be worked out. Instead,

171

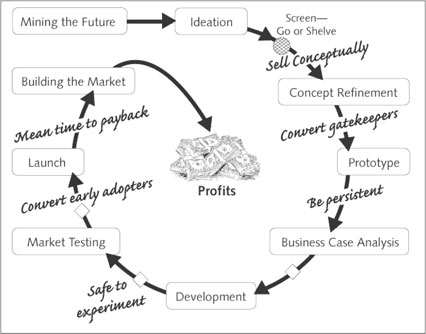

Figure 7. Idea to Implementation in Your Company. Selling ideas internally and externally is important at every stage.

make sure you demonstrate how the idea is in alignment with the firm’s growth targets, how it utilizes the firm’s core competencies. Use their hot button words. No matter who the audience is, be crystal clear in the way you describe your ideas so that nobody gets left behind in all the complexity. Remember: People must buy you before they’ll ever buy your idea.

Selling Strategy 2: Focus on the customer’s mean time to payback.

As companies focus on driving growth through innovation, they often concern themselves with mean time to payback: How long before we see a return on our investment in this new product, service, or market? Innovation adept firms focus instead on their customer’s mean time to payback. What they ask is: How long will it take their customer to begin enjoying the benefits of their investment in the new product or service?

172Not all products or services have a high mean time to payback implicit with their adoption. Purchasing Gillette’s Fusion razor and learning how to use it takes the consumer only a few minutes. Trying a new type of cold cereal, ditto. Purchasing a new car, same thing.

But consider the following products and the changes required by the customer to enjoy the benefits promised:

- Whirlpool’s Personal Valet is a cabinet-sized clothes refresher that removes odors and wrinkles using a chemical formula developed by Procter & Gamble. To be successful, Whirlpool must sell consumers an appliance they have never heard about, and they must learn a new approach to garment care. The valet will not remove stains, but it will take out wrinkles and deodorize clothes in 15-30 minutes.

- Although USA Today enjoyed phenomenal circulation growth and popularity among readers during its initial years of operation, advertisers were slow to accept the paper, since it was the first general interest daily newspaper that was sold nationally.

- Ralston Purina’s Secondnature is a new-to-the-world product: a house-training system for pet owners of dogs under 20 pounds.

- Autonation attempted to provide consumers with used-car superstores. The only problem: in quickly rolling out the concept without adequate testing, executives failed to see that used-car shoppers liked purchasing locally and didn’t want to drive far from home to shop.

Webvan’s Faulty Assumptions

Indeed, miscalculations at Webvan brought about its demise. In its brief, unhappy existence, the one thing that online grocer Webvan did not lack was boldness. The Foster City, California company grocery delivery company soon thereafter opened operations in ten metropolitan areas in the United States, raised $800 million in capital, and built a huge $40 million warehouse in Oakland, California, the first of many, as it inked a billion dollar contract to build 25 more across the country.

The size of seven football fields, the Oakland facility immediately became the world’s most advanced food factory, moving the equivalent stock of 17 supermarkets along miles of conveyor highways studded with scanners 173to track and direct every wine bottle and box of cereal. Nine massive carousels each moved 5,000 bins of products into place automatically for easy stocking.

Like many a failed idea, Webvan’s underlying assumptions—”build it and they will come”—turned out to be false. Yes, there were customers who valued the convenience of not having to go to the grocery store, but they did not sign up in nearly the numbers that Webvan needed to justify investments.

In retrospect, one of the key assumptions that Webvan’s designers apparently failed to understand was consumer behavior. For many shoppers, delegating the intimate task of foraging for food wasn’t something large numbers of them were willing to do at the drop of a hat. Squeezing fruit and eyeing just the right cut of pork loin involved making choices that they apparently didn’t believe could be turned over to others. “This isn’t like book purchasing,” one of many analysts was quoted as saying, “to get people to change their behavior on something this important to their lives is very difficult.”

Webvan isn’t alone in needing to study the amount of change an idea will require to be accepted and used by customers. Most innovations require customers to make a change, and ascertaining their willingness should be determined early in the idea’s development. Training your dog to use Ralston Purina’s Secondnature litter box takes time. Integrating General Electric’s new speed cooker, Advantium, into your kitchen usually requires the added expense and hassle of hiring an electrician to install 220 volts. Integrating shortened cooking times for items ranging from baked potatoes to roasts requires adaptations in your cooking style. Converting to grocery shopping via an online grocer is supposed to free up your time but takes time learning the new way.

Inertia is a huge force, as the time and trouble to switch vendors, banks, or insurance provider means that customers will overlook or forgive all sorts of customer service slights, despite the billions spent on advertising to convince customers that they will be better off once they have begun to use your product or service. Add to this prevailing attitude the customer’s creeping cynicism about what the payoff will actually be in terms of enhancing their quality of life. How much better off will your life be once you have Internet access in your car? While people often become early adopters for status reasons, how much do they really need to enhance their self-esteem in this manner?

174Selling Strategy 3: Make it safe for customers to experiment.

An innovation, as we’ve said, offers a different value proposition to the buyer that says, “the way you’re solving your problem today is not as good as the way you could be solving that problem.” But it also suggests to customers that they trade the security and safety of the way they solve their problem today with a new way that has potential dangers. It suggests, in other words, that they take a risk, a leap from the known to the unknown. That’s why it’s essential to put yourself in your customers’ shoes and ease their discomfort with risk-taking. True innovators:

- Promise safe experimentation. How can you make reversibility a way to get people to experiment with your idea? The age-old “money back guarantee” is certainly one way, but what about others?

- Use familiar terms. Early automakers used the term “horseless carriage” to get people to convert to the automobile. Thomas Edison, when he was attempting to convert people to using his electric lights, used familiar terms, and called them lamps.

- Encourage free trial. Starbucks often gives out samples of new beverages. Art Fry and his team at 3M gave out Post-it Notes to administrative assistants to encourage people to try the newfangled product. Give people reassurance that they can easily go back to the old way of doing things if they don’t like your new way. This lowers their resistance, and hopefully the results they achieve with your new way more than make up for the costs of shifting to your new way of doing things so they don’t wish to go back.

- Make purchasing easier. As we saw in Chapter 7, breakthrough products often come with enabling benefits that make them affordable. Cyrus McCormick sold his harvesting machine to farmers on credit—a strategy innovation that allowed thousands of farmers to pay him off over time.

Selling Strategy 4: Sell conceptually.

No matter how obvious the benefits, few ideas gain easy acceptance. You’ll experience resistance, and sometimes you may not be able to tell exactly 175where it’s coming from, internally or externally. You’ll encounter problems that you never could have foreseen. The market will react totally differently from what you or anyone on your team expected. So the experienced innovator knows to expect the unexpected and expect to have to continue to overcome objections, sell skeptics, and deal with the unexpected.

In the early 70s, GE Medical began a project to develop Computerized Axial Tomography, CAT scan technology for short. To get feedback from lead customers, the company invited 11 of the country’s leading radiologists to the Bahamas for a seven-day focus group. GE’s product developers wanted these potential adopters to help them determine possible applications for their product. These radiologists turned out to be extremely skeptical. “A small, niche opportunity,” was their uniform conclusion.

To its credit, the GE team pressed on, and in 1975, with its development effort well underway, they again sought the input of radiologists in an attempt to determine how many hospitals were likely to buy CT systems. Tom Lambert, responsible for marketing the new product, recalls the radiologists’ reaction:

“I’d say, ‘This [CT] machine will to do this and this.’ Their first question would be, ‘How much resolution does it have?’ And when I told them it had one-tenth of what they were using at the time, that was the end of the story. It took me several months to figure out what the problem was. Their view was, ‘I’ve been taught this way in medical school and this is how you do it. It’s always been done that way, always will be done that way. It works fine.’ They recognized their problems as being adequately addressed by available technology, so they didn’t see a need for a new technology and wondered why I was wasting their time.”

As it turned out, that wasn’t the end of it. General Electric’s CT machines became a highly successful breakthrough product for GE Medical but not until the team learned to sell conceptually.

Marketing an innovation, both internally and externally, depends on convincing people to adopt a new idea, but more importantly it demands that they change. Adoption of your idea is a learning process. It is undertaken either because it is required of the individual—by one’s company manager, say, or voluntarily, based on a complex set of beliefs, feelings, motives, and motivations, from “desire to impress others” to “not wanting to appear behind the times.”

176But such resistance is to be expected with truly new ways of doing things, no matter what the promised benefits, no matter the strength of the proffered value proposition.

Selling Strategy 5: Build markets for your products and services.

Developing new markets can sometimes be a slow, tedious process, yet when you do build a market, you are more apt to own that market. The impediments to building new markets are well established: customers are not anxious to substitute a new, unknown solution for one that is tried and true. They perceive the risks, correctly or incorrectly, as being too great.

Sometimes companies must learn this lesson the hard way, as was the case at DuPont. Working at DuPont’s experimental station in Wilmington, Delaware, chemist Stephanie Kwolek developed a mixture of liquid crystal polymers that performed like nothing she and her colleagues had ever seen. “We had it tested for strength and stiffness, and when the properties came back, we were amazed they were so high,” Kwolek told one interviewer. The new fiber had a tensile strength modulus of 450. Nylon, by contrast, has 55. It was five times stronger than steel.

Kwolek’s 1971 patent, co-held with Paul Morgan, was for a fiber DuPont named Kevlar. It revolutionized the synthetics industry and made billions of dollars for DuPont. Today Kevlar is everywhere—in police vests, army helmets, tennis rackets, mooring lines for cruise ships, skis, trawling nets, golf clubs, and racing sails. Kevlar gloves protect the hands of fishermen, auto workers, motorcyclists, gardeners, and oyster shuckers. Loggers wear Kevlar chainsaw chaps, and heads of state often wear Kevlar vests and raincoats. Embassies decorate with Kevlar curtains that can shield occupants. But breakthrough status was long in coming, because, former insiders say, DuPont was stuck in the “build it and they will come” paradigm. When DuPont invented nylon, Dacron, Teflon, and many other fibers, that’s exactly what had always happened. Nylon stockings went on the market in 1940, and women stood in line overnight outside their local hosiery shops so they could be the first to own a pair. Nylon made silk stockings all but obsolete and demand soared for the new material. But Kevlar customers didn’t come.

One of the initial new applications for Kevlar was supposed to be the tire industry. The future looked bright, so bright that Kevlar’s champions 177convinced senior management to build the first commercial plant, capable of making 45 million pounds of the fiber a year. But soon after construction started, tire manufacturers chose steel. Kevlar was too expensive, they concluded, and besides, car owners were attracted to the phrase “steel-belted radials.”

After tire makers turned Kevlar down, DuPont was dumbstruck. “Kevlar was the answer,” recalls a marketing manager for the fiber, “but we didn’t know for what.” Having never had to go out and build the market for its innovations, Kevlar floundered. The disjointed paradigm to find uses for the new products took over a decade and $900 million in capital expenditures to pull it off.

A disorganized search for uses involved numerous missteps and missed opportunities. Instead of DuPont seeing a possible use for its fiber being protective vests for police officers, it was the other way around. A crusader for lifesaving devices from the National Institute of Justice made that connection. The vests became so popular that some policemen, and even their wives, bought them with their own money when the departments didn’t have the funds. And instead of DuPont seeing a possible use for Kevlar in the military, it was the U.S. Army shopping for a fiber to replace nylon in flak jackets that came calling.

Belatedly, DuPont’s management saw the need to reinvent its market-building process. Market niches in protective vests and racing tires was fine, but tons of new applications were needed to justify the huge investment and to build Kevlar into a breakthrough that would drive significant top-line growth. Before, market-building skills at engineering had been piecemeal at best, but Kevlar was a turning point. DuPont realized the value of building the market, rather than waiting for the market to develop. The Kevlar group organized classes to learn how to sell ideas and then fanned out to call on potential users.

DuPont learned that the more innovative the product or service, the more likely it is that you must build a market for your offering. And to do that, the more essential it is to have a plan for building the market, even though your plan will have to be altered time and again. What markets will you penetrate first? How will you convert customers? How much time will it take?

Building markets for your products and services is the essence of innovation. Sometimes in the midst of obstacles you will wonder why you are going 178to all the trouble. Then, it is important to keep in mind the adage: no pain, no gain. Remember, when you build a market, so long as you keep on innovating and don’t rest on your laurels, you are more likely to own the lion’s share of that market.

Selling Strategy 6: Convert the early adopters and gatekeepers first.

Consider how the market developed for pocket calculators in the 1970s. Scientists and engineers were the early adopters of this product—it had clear advantages over the slide rule and log table—and they could easily justify the hefty price tags on early calculators. But even in these specialized markets, acceptance of calculators didn’t happen overnight. No doubt some engineers determined to ignore these new devices.

Buyers learn about new products and services from a wide variety of sources, of which advertising is said to be one of the least credible. Most credible? Testimonials from respected friends, colleagues, and coworkers who speak from personal experience. Indeed, peer pressure to “try it, you’ll like it,” is often at the top of lists of why people, following on the heels of the early adopters, decide to change. The desire not to appear “behind the times” is one reason consumers vote for the new way. Who are the gatekeepers that control and influence acceptance of your idea? It depends.

Selling Strategy 7: Be persistent.

The 3M team responsible for launching Post-it Notes was growing desperate. Senior management was threatening to kill the product as a loser. The product was out there in a few stores, but nobody was buying it. Getting retailers to stock the product was proving to be nearly impossible. Retailers didn’t understand the product, their customers weren’t clamoring for them, and who needed these silly little stacks of paper when you could just use scratch paper? What to do?

“Richmond,” someone suggested. And so Nicholson and Ramey took suitcases of the little sticky pads to the business district of Richmond, Virginia handing them out to passersby. It was a turning point. People started sticking them everywhere, finding all sorts of uses for them, and they began asking for them at retail stores. The rest, as they say, is innovation history. Post-it 179Notes have brought additional billions to 3M’s top and bottom line and became a sort of icon of this final ingredient of the innovation process.

How Colgate’s Total Dethroned Crest and Became America’s Top Toothpaste

In its first month of being launched in the North American market, Colgate-Palmolive’s Total toothpaste unseated long-reigning Crest to become the best-selling product in its category. Industry observers were universal in their praise of the product, which was called the biggest advance in oral care since fluoride was added to toothpaste in the 1950s. But they were even more lavish in praising Total’s launch, calling it one of the most spectacularly successful selling jobs in consumer product history. What Total did—the steps it took—provides us with important insights into selling new products and services in the global economy and driving top- and bottom-line growth accordingly.

Behind every breakthrough idea, there is a team of people whose passion, commitment, and selling savvy is unsurpassed. Two-hundred-person Team Total had one additional advantage: the leadership of veteran product manager Jack Haber. Brandweek once described Haber as a “discreetly ponytailed mensch, who seems to transcend the stereotype of a typical buttoned-up, high-powered executive, whose charm makes the impossible seem doable, even effortless, even a task as monumental as taking a blast at the reigning king of oral care.”

Unseating Crest was hardly a slam-dunk. The product’s development had been expensive and suffered a lengthy delay as the federal Food and Drug Administration weighed approval. Haber and his team had asked for and received $120 million for the introduction alone, making it the most expensive product launch in Colgate’s history.

Over the previous decade, the U.S. oral care market had been deluged with line extensions and incremental improvements. Consumers were jaded by endless claims for pastes that whitened, eradicated tartar, controlled bad breath, and aided in gum care. But through it all, Crest was barely bruised, steadily holding the number-one position since it pioneered fluoride 35 years before, just as baby boomers were getting their first molars. That turned out to be Crest’s vulnerable spot. Crest’s brand managers had apparently begun to believe their product, having withstood attacks from a slew of competitors, would always remain number one.

180What would it take to get those boomer consumers to look past the “look ma, no cavities” history with Crest and switch brands? Total’s bold answer: new benefits and a product that truly added new value.

Like Crest’s fluoride, Total contained a revolutionary new ingredient, Triclosan, a highly soluble antibiotic that with two daily brushings provided round-the-clock protection against gingivitis, plaque, cavities, tartar and bad breath. Total’s developers had discovered a way to bind Triclosan to teeth. (Patents for this unique bonding process guarantee Colgate exclusivity until 2008.)

After extensive reviews of Colgate’s clinical data, the FDA allowed Total to make first-ever claims for protection against gingivitis and plaque. These new benefits gave the product’s marketers unique bragging rights, but would consumers listen? With all the competitors’ line extensions and gimmickry in the category, launching the product would need a unique approach to convince consumers that this one was not just another pseudoinnovation, but was truly new and truly improved.

Building Buy-in Among Gatekeepers First

Upon winning FDA approval, the key question then became how to rise above the chatter of competing claims and communicate Total’s unique benefits to harried U.S. consumers? Colgate-Palmolive’s research indicated that two out of three consumers believed that a “fresh, clean mouth” was one of the top reasons for buying a particular toothpaste brand. But that hardly unearthed an unarticulated need that Total could latch onto.

To gain their attention, the Total Team felt they needed to change consumer awareness, making them aware that hidden problems such as gum disease, gingivitis, and plaque were bigger threats to their well-being, as they got older, than cavity protection. As their approach to selling Total took hold, the team hit on the “long-lasting protection” theme as the new formula’s unique selling proposition and the sales campaign began to take shape from there.

Television advertising came only after preparing the industry’s gatekeepers, namely dentists. Colgate dispatched, via overnight courier, 30 million samples of Total to dentists’ offices around the country. They spent $20 million informing dentists of the product’s therapeutic benefits, answering their questions, informing them of how Colgate developers had relied on leading dental schools to discover a way to bond Triclosan to teeth and how it was 181clinically proven to fight gingivitis. It was the only paste cleared to make such claims by the FDA.

That done, the team turned its attention to the distribution channel. “The whole process for Total was different,” recalls Lou Mignone, vice president of U.S. sales. “We did pre-planning with senior merchandising executives at the major retailers and worked with them on timing the introduction and getting the product to market as efficiently as possible.”

The team also coordinated the distribution process for the trade, bypassing warehouses and sending individual cases to stores, which ensured all retailers had their shipments within a week, versus the usual five to eight weeks. Then and only then did the team turn to television. One television spot showed a hurried young executive going through his busy day, as the sound of brushing follows him everywhere. “Now there’s a toothpaste so advanced,” observed the voiceover, “it even works when you’re not brushing.”

In my interview with the product’s champion, Jack Haber described a moment when he was sure that Team Total had come up with not only a breakthrough product but a breakthrough selling strategy as well. “At a dinner the night before a big sales meeting, before any speeches were given, everyone was so happy and so pumped we could have concluded the meeting then. I never saw such electricity in a room before and it translated because the marketing group had it, sales had it, R&D had it, buyers had it, retailers had it, and I just knew then that in a matter of a few weeks, consumers would have it too. We were all celebrating.”

Developing New Approaches to Selling Ideas

As Team Total surely knows, discovery and invention of a new product or service are not nearly enough. To derive growth from innovation, you have to build the buy-in for your idea, sometimes one customer at a time. You have to go out and knock on doors, and find people who can use your product. These days, as computer mouse inventor Douglas Engelbart put it, the biggest challenge isn’t how to innovate a better mousetrap, it’s how to get people to adopt your better mousetrap. Here are some key questions to ponder as you reflect on the ideas in this chapter.

- How good an evangelist are you? How have your persuasive skills and abilities been improving over the past, say, five years? How quickly and effectively do you identify the benefits and the value-added to be 182 derived by the customer? And to your subordinates, channel partners, and others on the management team?

- How effective has your firm been in recent years in launching products, services, and internal changes that require employee buy-in? What learning needed to take place? What assumptions proved invalid and what will you do differently next time?

- Thinking about an idea you had recently, who were the stakeholders you needed to convince to accept your idea? How effective were you in utilizing the skills outlined in this chapter?

- How does the sharing of best practices take place in your company in this all-important arena of selling new ideas? Are teams giving enough attention to this final, vital phase that is so critical to successful innovation?

There’s no question that successfully selling new ideas is the essential, capstone skill of innovation-adept companies and idea champions. In the public’s imagination, the act of selling often gets confused with hucksterism, manipulation, and unsavory practices. But as every sales and marketing professional knows, nothing happens until the sale is made, the customer hands over his or her hard-earned money and buys your new idea that good things start happening.

After you’ve pondered the questions posed above and throughout this chapter, consider this: It’s often the front-end of innovation that is considered fuzzy. But after working with numerous companies to improve their innovation processes, I often find that the real fuzziness lies at this, the back end of the process, and it needs major revamping such that selling ideas becomes a stepping stone rather than a stumbling block to driving growth.