12. Organizing What You Find

Are you this type? You go to the grocery store. You’re a whiz at doing the shopping, finding all the bargains, and reading all the nutritional labels. But when you get home, the groceries end up sitting on the counter forever because you never quite get around to putting them away.

This chapter is for you.

The most intricate set of information traps in the world will not help you if you’re not able to put your hands on the information you need, and organize the information you find in a compelling way. In this chapter, we’re going to look at strategies—lots of different strategies—for putting your information together and saving it. And because most of these strategies involve setting up client software on a single computer, we’re going to start with a really basic, portable strategy. From there, we’ll look at computer-based organizing solutions as well as Web-based solutions.

A Very Simple, Portable Strategy

Most of this chapter is going to cover software that you install on a single computer. That’ll suit most people but not be particularly useful to those folks who have to move around between computers or check information traps in several different places. There are Web-based options as well, but for reasons of access or security you may not want to use those. The strategy I’m going to outline here is really step one—a ground-level option to help you get started. Later we’ll get into more involved options.

The beauty of using a text editor

The most basic, extremely simple organizer is just a text editor. Its big pro is that plain ASCII text files are compatible with just about everything (and they stay compatible—ten years from now you will still be able to find a text editor for your ASCII files). Furthermore you can fit a lot of information in an ASCII file, and such files are very portable. The big disadvantage is that they only store text—they don’t store multimedia, and they don’t store fancy formatting (though they will store HTML files; you’ll just see the formatting tags instead of the formatting itself).

Text files are how I do most of my initial information organizing. I use a program called UltraEdit; it’s available at ultraedit.com. (In fact, I’m using it to write this chapter right now!) It allows you to open several different text files at a time. What I normally do is create one file for whatever I’m working on at the moment, leave it open, and toss in information as I find it. That way I know that everything I need is in one file at any particular time, and from there I can write up a Web page, a report, or an e-mail, and copy-and-paste it where it needs to go.

The ability to copy-and-paste my text and not have to worry about formatting weirdness is the primary reason I use this method of organizing information instead of setting up a Microsoft Word file or some other program that uses non-ASCII formatting.

And text files are usually small because, well, they’re just text. And even when you have a big text file they’re usually manageable. I’ve thrown multi-megabyte files at UltraEdit and they’ve been handled fine. When I need to take text files somewhere, I put them on a flash drive (a very small portable hard drive; you often see them on keychains or lanyards). I can carry them knowing I don’t have to worry about special configuration files or whether or not a different computer has a particular program. (If worse comes to worst, Firefox will open a text file!)

UltraEdit isn’t free; it costs $39.95. But if you want to try something a little less expensive, there are lots of free text editors available, including EditPad Lite (editpadpro.com/editpadlite.html), NoteTab Light (notetab.com/ntl.php), Cream (cream.sourceforge.net), and Metapad (liquidninja.com/metapad/).

Another portable option: wikis

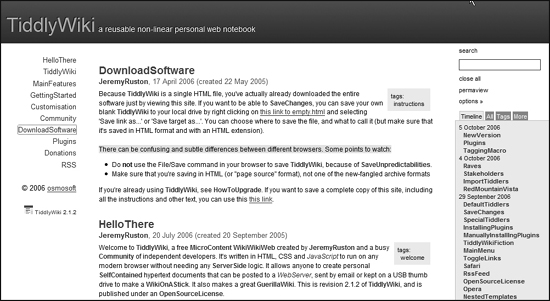

The ability to toss a text file on a flash drive and head out the door makes keeping data text-based very useful to me. But there are other portable information options as well. There are wikis, which are structures that allow groups of people to add content collaboratively. (You can get more detail about wikis and their history at en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wiki.) Can you imagine if something like that was portable? TiddlyWiki, also known as WikiOnAStick, is available at tiddlywiki.com. It allows you to set up a wiki that’s portable on a Flash drive, and which you can open and edit in a browser. In fact, the instant you open the TiddlyWiki home page, you’ve downloaded the software (Figure 13.1).

Figure 13.1. TiddlyWiki allows you to create outlines of information and carry them on a flash drive. Acquiring it is as simple as visiting the home page.

Maybe you’re not sure about what browsers will be available on a computer when you get to where you’re going. In that case you may want to also put Portable Firefox (portableapps.com/apps/internet/firefox_portable) on your flash drive. Portable Firefox is a version of Firefox designed to be as portable as possible. It takes your cookies, bookmarks, and other browser information with you as you move around.

If you don’t want to use client-based software, or at least software that you can’t put on a flash drive and carry with you, your organizing options are going to be limited to what you can find on the Web, which may carry with it security and privacy implications. You won’t have to worry about being around your computer all the time, but how you can manipulate your data will be limited.

Let’s look at options beyond simplicity now, starting with more extensive client-side software options.

Organizing Information on a Single Machine

If you’re going to be doing all your work on a single machine, the advantage is that you’re going to be doing all your work on a single machine. And that means you can can “pull back” from the idea of just organizing the information that you’re gathering and focus on a bigger idea—indexing the contents of an entire machine! From there you can “zoom down” to organizing information on a project level.

It wasn’t too long ago that trying to search an entire computer was very tedious. Windows offers tools that allow you to do it but they’re slow and sometimes the search results don’t give you the information you need.

But now Web-based search engines have begun offering tools that allow you to index the contents of your computer (though not all contents—more about that shortly). These programs go through your computer rather like a search engine “spider” goes through a Web site, and builds up an index of your computer’s contents. They then allow you to search the content by keyword, getting results that sometimes include a preview of the item, when it was created, and so on. The search engine technology offered by these indexers allows you to do deeper and faster searching on your computer than you can usually do with the Windows search utility. We’ll take a look at three of the search engine desktop searchers here, from Ask, Google, and Yahoo.

Search-engine indexers for your computer

Warning! These indexers are, for the most part, Windows-only. I suspect that as the Apple brand has gotten very popular (thanks to the iPod, iTunes, and other Applesque innovations), we’ll be seeing a greater effort to support those folks who use a Mac. Watch the offerings from the search engines to see if they take the lead in offering Mac support for their products.

Ask Desktop

Ask Desktop (sp.ask.com/docs/desktop/) requires Windows 2000 with SP3 or Windows XP on a computer with at least 500MHz and 128 MB RAM minimum.

Once you’ve installed Ask Desktop, as with any other indexer, you’ll have to wait for it to finish indexing your computer before you make the most of it. When you first install it, Ask will open a browser window and show that it’s indexing your computer, along with a notification of the last files indexed and how many files total have been indexed. How long the indexing takes depends on how large your hard drive is and how good your computer’s processor is. My experience is that it usually takes an hour or so. Ask keeps refreshing the number of files that you have indexed.

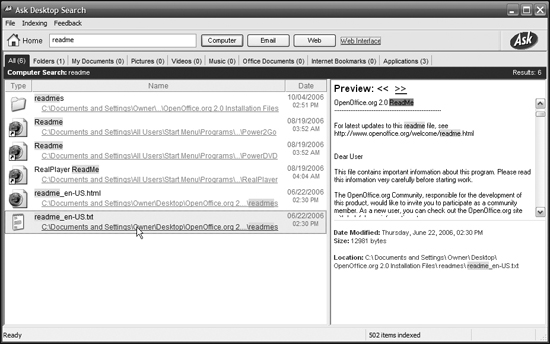

Once your hard drive is indexed, you can search within your browser, or you can open up the client interface. (I prefer the client interface, as it gives me access to the preferences for the program, allows me to download the latest version, and lets me set the indexing speed for slow or fast.) Searching is by simple keyword; you can search the computer, the Web, or your e-mail (Outlook or Outlook Express e-mail). When you run a search, your results will be divided up into tabs (Figure 13.2).

Figure 13.2. The Ask Desktop Search breaks up search results across several different categories.

Some types of files can be previewed in the right pane. The first tab will have all the results, but the other tabs will be divided into folders, pictures, applications, and so on. On the left of the screen will be results, while on the right is summary information about each file as you click on it. Some files, like audio and graphics files, will actually preview in the right side of the screen (sounds will play, you’ll get a thumbnail of images, and so on). Double-click on the filename to open the file itself.

Ask Desktop supports Microsoft Office versions 2000 and higher (this is what Ask claims, but I found that the Desktop Search also indexed files made with Office 97), Outlook, Outlook Express, PDF and ZIP files, image files (.jpg, .gif, and .png), music files (.mp3, .wma, and .wav), video files (.mpg and .wmv), several comment formats, HTML, and TXT files.

Ask does not offer esoteric file format indexing; it’s actually pretty limited in what it does index. On the other hand, Ask has a small file footprint and won’t put a strain on a slower computer. If you have an older computer and you want to index documents that are mostly from Microsoft applications, start here.

Google Desktop

Google Desktop (desktop.google.com) requires Windows XP or Windows 2000 SP 3+.

It just happens to have a desktop search engine, and also offers “gadgets” for desktop information, as well as the ability to index the contents of your GMail account. Because of this, you’ll have to supply a little bit of additional information when you start up the application; you’ll need to specify whether you want to index your GMail information (assuming you have GMail) as well as whether you want to get Google “Gadget” content (little programs that you can set up on your desktop) and whether you want to use Google as your default search engine in Internet Explorer.

You’ll also have to specify whether you want usage information to go to Google or not. Google uses the information you send it to personalize the kind of information that displays in the sidebar, but if you have privacy issues, you can choose not to send information to Google (and thus disable some of the advanced features).

Once you have answered these questions, Google starts indexing your hard drive (giving you an estimate for how long it will take) and displays your sidebar, which includes things like photos, news, weather, and a little scratch pad where you can save notes. If you want more, there are literally hundreds of Google Desktop Gadgets available at desktop.google.com/plugins/. By default, Google Desktop will only index items when your computer is idle. You may choose to start indexing immediately, but it could slow down your computer.

Google Desktop’s search search is rock simple because—surprise!—it looks just like Google’s regular Web search! Google Desktop’s search runs inside your browser (Figure 13.3).

Figure 13.3. Google Desktop’s search looks just like Google’s regular search.

Searching is by keyword, and the search results look as Googly as the search page. Search results show the name of the file and its location (and a snippet if Google can index that file), as well as when it was indexed and an option to open the folder in which the file resides. You can sort your results by relevance or date (since Google’s indexing your desktop, it can determine the file dates of items). All items are presented by default in the search results, but you can also choose to see only e-mails, files, Web history, chats, or other files.

There may be a little additional information depending on the type of file being returned in the results. Image files have thumbnails in the search results, while text files have caches.

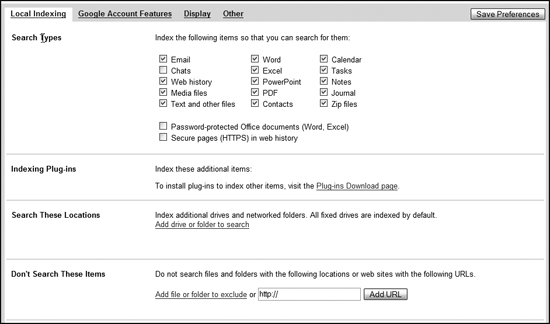

You can use Google Desktop as just a simple search, but you do have some other options that you can see in the preferences. The Desktop Preferences link is next to the query box on the Google Desktop home page (Figure 13.4).

Figure 13.4. Control what’s being indexed via Google Desktop’s preferences.

Preferences are set up in tabs and include specifying which file types you want to index and whether you want to add any other filetypes for indexing. (Google has a subset of its gadget page at desktop.google.com/plugins/c/index/all.html?hl=en that will give you access to lots of additional indexing plug-ins, from Belkasoft’s ICQ plug-in for GDS Pro to Larry’s Help File indexer.)

You can also add or remove files and folders from your indexing, as well as encrypt your index and data files (though this will impact your computer’s performance). Finally you can choose to have your desktop’s indexed files available for search across several desktops. Because Google stores your files on its servers, you can search your files via your Google account from no matter where you are. This has serious privacy and security implications; think carefully before you decide to do this.

Google Desktop supports a variety of formats including Microsoft Office, MSN and AOL Instant Messenger, Google Talk, PDF, music, images, and ZIP files. In addition Google, as previously mentioned, also offers dozens of plug-ins for searching more obscure file types.

Google Desktop not only offers lots of plug-ins for extreme flexibility, it also offers the ability to index across computers, if you do your trapping from more than one place. However, this ability comes with some privacy and security risk, as your data files will be stored away from your computer. Think carefully about using it.

Yahoo Desktop

Yahoo Desktop (desktop.yahoo.com) requires Windows XP or Windows 2000 SP 3+.

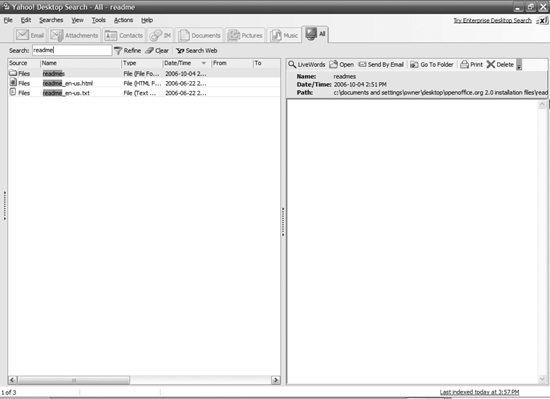

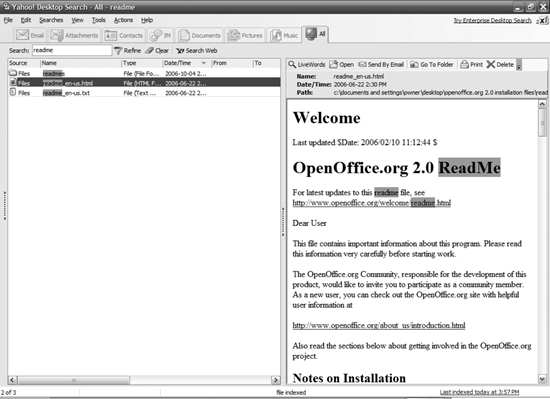

When you download Yahoo Desktop, you not only get the application, you also get the Yahoo Toolbar, which is an installation option when you first install the program. When the program has been completely installed, you also have the option of logging in with your Yahoo account so that Yahoo can index your Yahoo Messenger conversations and Yahoo address book contacts. If you don’t have a Yahoo account or don’t want to share that information, just click Cancel. When you first launch Yahoo Desktop, you get the should-be-familiar-by-now search on the left and preview on the right (Figure 13.5).

Figure 13.5. Yahoo uses a client application instead of a browser and filters to search for keywords.

Unlike the other two desktop indexers, Yahoo Desktop has a client interface and doesn’t work through the browser. Furthermore, Yahoo Desktop defaults to showing just results from your e-mail. You’ll have to view the All tab, furthest to the right on the results page, to see all your results. Otherwise, the Yahoo Desktop results page is excellent, showing Microsoft Office documents in preview mode and even playing multimedia (Figure 13.6).

Figure 13.6. Yahoo Desktop previews a variety of documents excellently, including HTML.

A handy Refine button lets you easily narrow down searches further by a variety of factors, including date/time, size, and path. I found both the searching and the indexing to be very quick; you can increase the speed and effectiveness of the indexing by choosing Tools > Options from the main menu and then choosing Indexing Priority from the Options screen. While you’re here, you can also choose some other options for indexing and searching with Yahoo Desktop.

Yahoo supports several different kinds of files, including Outlook, Outlook Express, Thunderbird, Microsoft Office, PDF, and, of course, plain text and HTML files.

Yahoo also has a free downloadable expansion pack that allows indexing of an additional 300 file types. You can download the pack and get a full list of the additional file types at desktop.yahoo.com/filetypes.

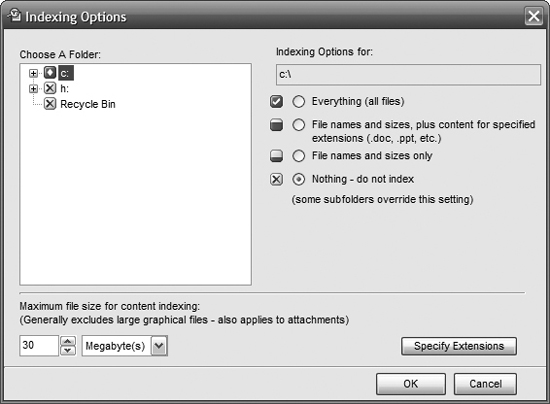

You’ll want to spend some time in the preferences menu that I mentioned above. It was here that I had to do a little additional tweaking. For example, I had to set as a preference that media files (such as music files) would play automatically in the preview pane. Without doing this, I would have to launch them manually every time I found a music file. Yahoo Desktop Search also has a More Indexing option that shows you exactly how much is going to be indexed on each folder of your hard drive (Figure 13.7).

Figure 13.7. Be sure to check the indexing options to see what Yahoo Desktop is actually getting in its index.

Yahoo Desktop seems to not index the contents of your Program Files directory by default. If you’ve installed programs in that folder, and the information generated by the programs is also kept in that directory, you want to make sure that at least specific subfolders within the program folder are being indexed. This is doubly important if you have programs there that are critical to your information trapping.

Also, be sure to check the default indexing for e-mail clients. It appears that Yahoo Desktop does not index e-mail by default. If you’re sharing a computer or have security/privacy concerns, this is probably a good thing. However, if you have a computer to yourself and you’re doing a lot of collaborative searching that’s coordinated by e-mail, you definitely want to make sure it’s being indexed!

Fleshing Out Client-Side Options

Computer-level search engines are a good start when you want to make the information on your machine findable. But from there you actually need to organize the information relevant to your topic, and computer-level search engines are not going to help you stash away the stuff that you find while you’re browsing the Web. For that you need an information organizer. I’ve got three for you to look at: Net Snippets, Surfulater, and Onfolio.

What these programs do, for the most part, is work with your browser. As you’re browsing you might find a story you find interesting, or some text, or a page. These information organizers allow you to take what you come across and put it into a format that makes it easy to organize. They range from free to over $100, and they all have a bit of a learning curve. If you use Internet Explorer, you’ll have no problem using any of these offerings. If you use Firefox, you should be able to use them with no trouble, but you might have to install extensions. However, if you use Opera you’re probably out of luck: I found that, for the most part, these programs were not Opera-compatible.

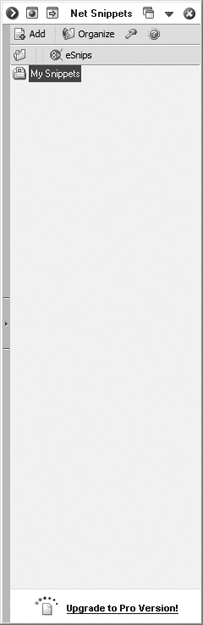

Net Snippets

Net Snippets (netsnippets.com) comes in a free and a couple of paid versions, and works with Firefox and Internet Explorer. If you want to use Net Snippets with Mozilla or Firefox, you’ll have to install a Net Snippets button, which you can learn more about at netsnippets.com/mozilla/install.asp. Once you’ve installed Net Snippets (and the button if you’re using Firefox), you’ll see a little Net Snippets button on your toolbar. Click it and you’ll get a little sidebar next to your browser (Figure 13.8).

Figure 13.8. Start your information gathering with Net Snippets’ sidebar.

Here you can create a set of folders to organize your content (which I recommend if you’re covering several different topics). If you want to add the contents of a page you’re viewing, right-click on the page you want and choose Add Page to Net Snippets. You’ll get a popup window where you can specify the importance of the save, make notes, and modify the page to a certain extent by removing formatting, converting to text-only, and so on (Figure 13.9). Once you’re finished, you save the page to Net Snippets.

Figure 13.9. Once you “snip” an item, you can set its importance and add notes.

This is a useful tool, but you do have to use it—if you only save half your pages you’re going to end up frustrated. Net Snippets does allow you to do keyword searching as well as look at the pages you saved within the last 7 or 30 days.

There is a free version of Net Snippets and two pay versions; standard for $79.95 and professional for $129.95. You can get more information about the different versions of Net Snippets at netsnippets.com/compare.htm.

Surfulater

Surfulater (surfulater.com) is also available for Firefox and IE. Once you’ve installed it, and installed the extension for Firefox if necessary, you’ll see that you get a lot of functionality just from the right-click menu while you’re browsing.

As you’re browsing, you may find some information you want to keep. Right-click in the body of the page you want to keep, and you’ll get options to save the page, to save the article plus the page, or to just add the article. When you’ve done that you’ll get a window that shows you what you’ve saved. Note that if you highlight text on the page before you choose an article to save, you’ll end up with a lot more information saved in Surfulater (Figure 13.10).

Figure 13.10. If you highlight text before saving an item, Surfulater will grab more text.

If you look at the left side of the screen you’ll see that Surfulater saves its pages in an outline format. You can set up several different folders and organize the information you want that way. If you’re monitoring and gathering a lot of information on several different topics this is pretty much critical; while you can search Surfulater by keyword, organizing your materials at the onset makes it easy to browse as well.

Surfulater costs $35 but a free trial version is available.

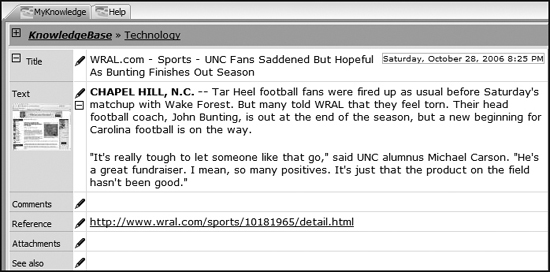

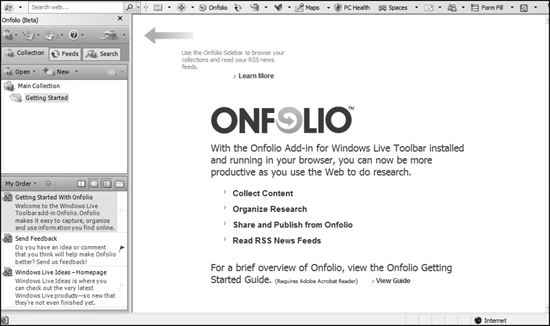

Onfolio

Onfolio (onfolio.com) used to be an independent company, but in 2006 it was purchased by Microsoft and is now a free download that’s incorporated with the Windows Live Toolbar.

To use Onfolio, you’ll have to install the Windows Live Toolbar (available at toolbar.live.com/) and then install the Onfolio button (which you can get at onfolio.com).

Onfolio is accessible from the browser in two ways. you can right-click and get the option to save a page or a site to Onfolio, or you can click on the Onfolio button in your Windows Live Toolbar. Onfolio launches as a browser sidebar (Figure 13.11).

Figure 13.11. Onfolio is part of the Windows Live Toolbar (above) but launches in a sidebar (left).

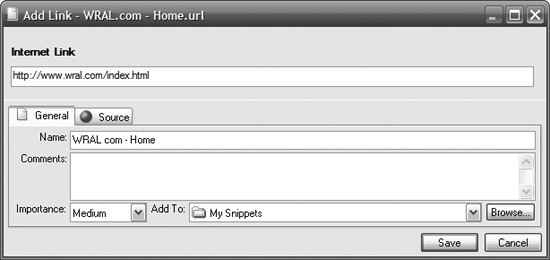

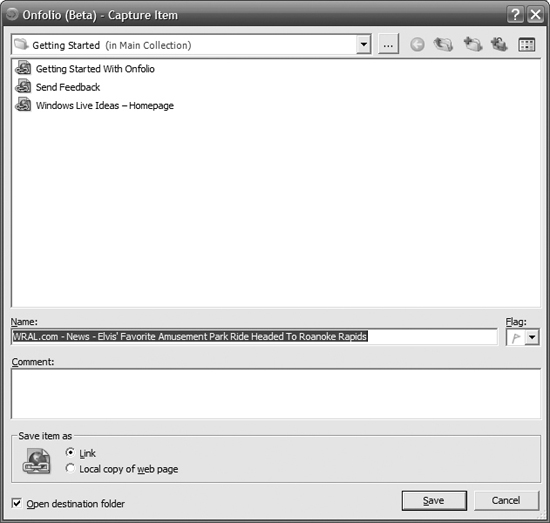

Again, right-clicking brings you a lot of options in Onfolio; when you choose to save pages, you’re given a popup window to enter any notes you want to enter, name the page, and save the page as either a link or as an actual local copy of the page. I save actual pages whenever possible, realizing that there’s no telling how quickly a page might vanish off the Internet. If you have space limitations, however, you might want to limit yourself to saving URLs only (Figure 13.12).

Figure 13.12. Onfolio’s options for saving a page.

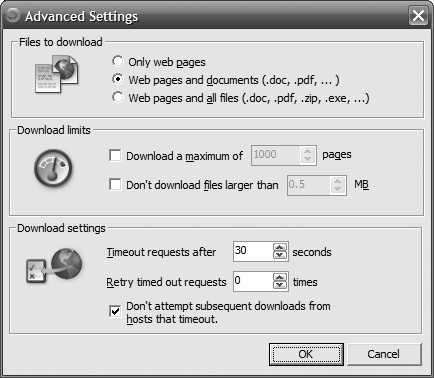

In addition to having the option of saving a single page, you also have the option of saving an entire Web site. Now as you might imagine, this can be a very extensive, not to mention time-consuming, thing to do. My site, ResearchBuzz, has thousands of pages. So when you open the save site dialog you get a window similar to the save page window, but it asks you how many “levels down” you want to save. Be sure to use the “Advanced” dialog, which lets you specify what kind of files you want to download (just Web pages, or PDF files, .doc files, etc.), the maximum number of files you want to download, and how you want Onfolio to respond to timeouts (Figure 13.13).

Figure 13.13. Be sure to use the advanced options if you save an entire site! You’ll want to set limits on how much you download.

Like Surfulater, Onfolio offers the ability to organize your saved materials into folders, and again they’re keyword-searchable. Right-clicking on an item you’ve saved gives you the option to do a variety of things, including flagging the item with one of many colors, editing comments, exporting the contents, or even “blogging” the item you’ve found (Figure 13.14). (You need to configure what blog you use in Onfolio; supported platforms include Blogger, LiveJournal, and TypePad.)

Figure 13.14. Once you’ve saved a page, you can edit it, flag it, even blog it.

I can’t imagine too many scenarios where you’d want to save the entire contents of a Web site. Perhaps if you’re doing competitive intelligence and want to go through a company’s Web site and see what they have, or if you find an online library and find all the contents very relevant and very useful. If you save entire Web sites, be sure to put a maximum page download limit, lest you discover that the site you’re targeting has a secret stash of press releases and you’re going to be downloading for the next two days.

Choosing the best program

Which of these programs do you want to use? If you want something fairly simple to use, try Surfulater. If you’re looking for something that has the capacity to download large files, look into Onfolio. And if you’re looking for something that offers a full package, from getting the information to turning it into a nice report, try Net Snippets.

I’ve presented you with some pretty heavy-duty offerings for client-side information organizing. Software like Onfolio and Net Snippets can take an information-monitoring project all the way from the gathering to the publishing stage. And that’s as it should be; all the information is installed on your computer, pages can be saved in their entirety, and you’re operating from your own “workbench.”

But you may find that a client-based organizing solution is not for you. You want to be able to do your searching across several different computers, or create a place of organization that several different people can access. Unless you’re all in one room together, that’s hard to do from a single computer! In this case, you might want to use Web-based organizing solutions, which I cover next.

Web-Based Organizing Options

The intention of this type of solution is the same as client-based solutions—to help you organize the information you find. But in execution, Web-based solutions are a little different. There may be a limit to how much you can have stored on a site. With your speed of access there may be only so much you want to access at a time. You may have security or privacy concerns.

Like going from plain text files to something really extensive like Onfolio, you have your choice in Web-based solutions, from the really basic to the really extensive. We’ll start with the basic and then get more complex.

When I say simple, I mean simple. I mean what are basically bookmarks online. For just saving a list of URLs and sites, I like using tagging sites like del.icio.us and RawSugar.

Tagging sites

We have discussed tagging earlier in the book. Now let’s look at it briefly from a user perspective as opposed to a researcher perspective.

Tagging sites allow you to save pointers to Web sites with both descriptions and tags. And as we’ve seen earlier, if enough people participate in a site that allows tags, then soon you develop a very large and active collection of resources that are searchable by keyword.

Because it is currently the eminent tagging site and because there are so many tools to make using it easier, I’m going to cover del.icio.us here. But I’m going to also mention other tagging sites that you may want to check out.

For all that I love about del.icio.us (del.icio.us/), I can’t stand the name (I can’t seem to stop typing it incorrectly), so as you’ve probably already noticed, I call it Del instead. To use Del, you’ll need to register, which requires a user name, password, and e-mail. Once you’ve confirmed and set up your account, you have a couple of options.

The first option is to take ten minutes or so and try out some keywords, see what other Del users have bookmarked for the keywords in which you’re interested. This will potentially give you some new resources to put in Del, as well as some ideas as to what keywords you should be using to tag your resources.

The second thing you can do is start surfing and dropping things into del.icio.us as you find them. There are a lot of tools available to make this easy.

Del itself offers one at del.icio.us/help/buttons; it’s a bookmarklet to both see your Del bookmarks and to add bookmarks to your Del site. Quick Online Tips has a bunch of alternate bookmarklets that add a little more functionality at quickonlinetips.com/archives/2005/02/absolutely-delicious-complete-tools-collection/.

There are Firefox extensions to make posting to del.icio.us easier at addons.mozilla.org/extensions/moreinfo.php?application=firefox&id=527 and polarhome.com:753/~pwlin05/delic123/. And if you get a little crazy and post so many things to del.icio.us that you lose track of whether you’ve already posted them or not, there’s Familiar Taste, which is a Greasemonkey extension that lets you check to see if you’ve already added an item to your del.icio.us bookmarks. It’s at blackperl.com/javascript/greasemonkey/ft/.

If you’re concerned about keeping your research and your URLs private, Del may not be for you. It’s really designed as a site that aggregates bookmarks and interesting sites. If your overwhelming concern is keeping your bookmarks private, try Boz at sandbox.sourcelabs.com/boz/, which encrypts your bookmarks on your browser.

The following are some other bookmark/tagging sites you might find useful:

• MyBookmarks (mybookmarks.com) is free and gives you the option to make bookmarks publicly available.

• Furl (furl.net), which is brought to you by LookSmart, lets you not only save a link to a page but also a cache of a page. The window for adding a link to your archive includes the option to rate the page as well as mark it private and to assign to it one of several categories.

• Yahoo’s Bookmarks (bookmarks.yahoo.com/config/set_bookmark) is good for people who already have a Yahoo account and don’t want to do more than manage and keep a set of bookmarks online. It’s not heavy-duty, doesn’t offer a lot of tagging and saving features like some of the other utilities in this chapter, but it’s a good basic bookmark manager, especially if you’re already using Yahoo Directory to start with.

• Simpy (simpy.com) looks similar to del.icio.us, but offers a pull-down menu to specify whether an entered bookmark is public or private. You also have the option of sending a link to other people at the time you’re adding it to your directory of bookmarks. Simpy also allows you to sync the bookmarks in its service with del.icio.us.

• RawSugar (rawsugar.com) is a tagging resource like del.icio.us, but is rather newer. In addition to the tagging option, RawSugar users can see the latest links added to the site and do regular Web searching via Google in addition to the tag searching of RawSugar’s archives. (If you search for something that isn’t found at RawSugar, it automatically reruns the search using Google.)

The sites I just mentioned here are basic bookmark/tagging sites. But we can get a little more extensive than that, by looking at Web-based resources that are designed to act more like a research partner for you. If you tend to move around between several different computers and you don’t have much in the line of security concerns, online organizing resources can be very useful as they’re accessible all the time and from anywhere. They come in several different flavors, from page keepers to free-form databases to wikis. We’ll look at several different examples.

Extensive Web-based organizing sites

Maybe you want something that’s more extensive than just bookmarks, but you want to be able to access it from any computer. In that case you might want to consider a Web-based organizing site. These sites offer the ability to extensively organize information yet access it from any computer. Most of them have a bit of a learning curve, though, so be prepared to invest some time in getting used to them.

eSnips

eSnips (esnips.com) is a service of Net Snippets, which we covered earlier in this chapter. The differences are that the service is online, and you get 1GB of space to hold the snips of information from the Web or from your computer that you want to save.

Registration is free. Once you’ve confirmed your registration, you’re invited to download an eSnips toolbar (which works in Internet Explorer, Firefox, and Netscape). You can also get an extension for Firefox. The eSnips toolbar “floats” on your desktop, giving you a quick way to save snippets you find to your online eSnips account. If you want to save lots of “bits” of information and are less interested in whole pages and sites, eSnips is quite useful.

OnlineHomeBase

OnlineHomeBase (onlinehomebase.com) is a “free-form” information keeper. Instead of having to figure out how you’ll bookmark something, or structure it so it fits into an existing infrastructure, you can use Online-HomeBase to create collections of free-form information, in addition to organizing the people who need the information.

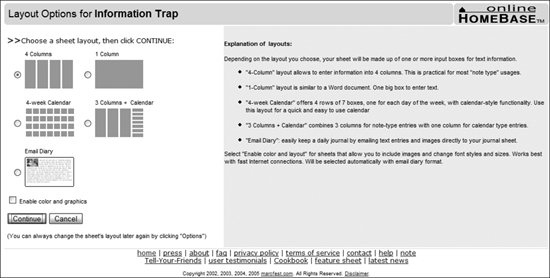

OnlineHomeBase is a subscription service costing $2.95 a month, but a free 14-day trial is available. Once you’ve registered, you’ll be taken on a quick tour. Take the tour; it’s worth it. You’ll then have the option to create your new HomeBase; you have several different layout options, including three columns with a calendar and even a daily diary which you update by sending e-mail (Figure 13.15).

Figure 13.15. OnlineHomeBase gives you several different layout and formatting options.

The HomeBase consists of two large parts; an online calendar and an online notepad. Don’t be put off by the word “notepad”; you can actually upload images and links into the notepad. (Note that some of this functionality works best with Internet Explorer.) There’s also a calendar where you can put events and reminders. If you don’t mind using a little geeky formatting (a couple of semicolons) you can actually e-mail yourself reminders of events. With a little more text formatting you can e-mail other people reminders of events, and actually get reminders on your cell phone.

OnlineHomeBase is not the ideal solution if you’re a) married to Opera or another more obscure browser; b) needing a start-to-finish infrastructure for keeping your information and developing your reports; or c) concerned about having to do a little text-formatting geekery. But if you’re in a small group of people and you want a basic tool for collaboration, and a tool would come in handy, this is useful. And it’s very inexpensive. Note that the service does include only 10MB of online storage, which nowadays is pretty paltry. Don’t choose this service if you’re going to upload a lot of graphics and files that’ll eat up that space!

TWiki

No no, not the little robot from Buck Rogers. TWiki (twiki.org) is a wiki developed for sharing information between a group of people across an enterprise.

As an information-organizing solution, this is probably the largest and most complex thing I’m going to mention in this chapter. It’s actually a free, open source software solution that’s being used on many corporate sites (the Web site lists a variety of clients that use it, including Yahoo, Motorola, and Disney. For obvious reasons most of these sites use TWiki behind a corporate firewall). Since the whole point of a wiki is that it’s editable by any member of a team that’s using it, this is great when you have large groups of people working together on an information-gathering project.

Furthermore, TWiki has been extended by a large set of plug-ins, including a calendar and access to databases and RSS feeds. While this software is free, it will require a huge investment in time and training to make the most of it for a project. If you need an enterprise-size solution for your information gathering or organizing, I urge you to try TWiki. Independent researchers and those working in small groups in the same place will likely find it overkill.

Backflip

Backflip (backflip.com) is another information manager that’s more about gathering and managing pages than it is about gathering and managing small bits of information. Like many of the other resources mentioned in this book, it’s a free service. Unlike some of the other resources mentioned in this book, it’s not designed to share bookmarks. Backflip bookmarks are private by default; this is idea for a solo researcher who doesn’t want to share his or her bookmarks even inadvertently.

When you’ve registered, you’ll have the option of importing your bookmarks as well as generating some general-level folders for organizing your bookmarks. For the information trapper who wants to use these tools to organize a few different topics, most of these folders probably aren’t necessary.

There are also other ways to view your pages as well, including looking at your most popular pages as well as your most recently added pages. Backflip has a bevy of tools that you can add to your browser to make “backflipping” pages easily; however, if your browsing isn’t proving very inspirational, you can also check out pages that are being backflipped often, as well as the contents of publicly available folders (remember, Backflip bookmarks are private by default, but there is an option to make them public).

This chapter has covered just some of the solutions you can use to gather, share, and organize your information. There are lots more. To find more resources to experiment with, try searching Google or Yahoo for online bookmark managers or information organizers.

Sticking to a Strategy

The most important thing is to have some kind of strategy for how you’re going to accumulate your information (and share it if you’re working within a group). Maybe you’ll settle on something simple, like the multiple-tab text editor that I use. Or maybe you need to work with several different people across a huge company, and you need an elaborate solution like TWiki. No matter what you finally choose, stick with it for at least a month. It takes that amount of time to develop a habit to save the information as you trap it. Don’t say to yourself, “I’ll find this later,” or “I’ll remember where this is.” I promise you: you won’t. Trap as you go. (For what it’s worth, I have to remind myself of this all the time too!)

Accumulating and organizing the information you find is only the second step in your three-part process. The first part is to find and monitor the information. The second part is to accumulate and organize it, and the third part is to reuse and republish it, which we’ll look at in the next chapter.