Chapter 10. Templates

You’ve learned a lot about template rules—how to create them, how to write patterns that trigger them, and how to generate results from them. You should be familiar with the following concepts about templates:

Template rules attempt to match patterns in a source document. A pattern is a subset of an expression, which is mostly used to match child elements and attributes using the child and attribute axes. (You can also use predicates, plus the

id( )andkey( )functions. You learned about predicates in Chapter 4 and aboutid( )in Chapter 5, and you will learn aboutkey( )in the next chapter.)When a pattern is matched in a source document, the content of the template (called a sequence constructor in XSLT 2.0) is instantiated or written out to the result tree.

When

apply-templatesis used in atemplateelement, it processes the children of the matched pattern, searching for other template rules that match those children.If the

selectattribute is used onapply-templates, it processes the children of the matched pattern that are specifically named in the attribute, searching for template rules that match those nodes so named. Theselectattribute can contain an expression.Built-in templates do behind-the-scenes work in processing nodes that may not be explicitly identified in templates rules, such as text nodes.

This chapter discusses additional issues related to templates,

namely, what template priority is, how to create and call named

templates, how to use parameters with templates using

with-param, what modes are and how to use them

(the mode attribute), and finally some additional

details on built-in templates.

Template Priority

What happens if you have more than one template rule that matches the exact same pattern, or more than one template rule with different patterns that happen to match the exact same nodes? Which template, if any, gets instantiated? Multiple templates matching the same node present a problem. When this happens, an XSLT processor has the option to stop processing and recover from the error, or recover from the error after issuing a warning. The way a processor recovers from conflicting templates is to instantiate only the last template in a stylesheet that matches the pattern. I’ll show you what I mean.

Example 10-1, the document ri.xml in examples/ch10, lists the five counties in the state of Rhode Island in the U.S.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="US-ASCII"?> <state name="Rhode Island"> <county>Bristol</county> <county>Kent</county> <county>Newport</county> <county>Providence</county> <county>Washington</county> </state>

The stylesheet

last.xsl

,

shown in Example 10-2, has two templates that match

the pattern for the state element node, each

producing a different result.

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0" xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform">

<xsl:output method="xml" indent="yes"/>

<xsl:template match="/">

<county state="{state/@name}">

<xsl:apply-templates select="state"/>

</county>

</xsl:template>

<xsl:template match="state">

<xsl:apply-templates select="county"/>

</xsl:template>

<xsl:template match="state">

<xsl:apply-templates select="county[starts-with(.,'K')]"/>

</xsl:template>

<xsl:template match="county">

<name><xsl:apply-templates/></name>

</xsl:template>

</xsl:stylesheet>In order of appearance, the first template that matches

state elements selects all the

county children of state. The

second template that matches state selects only

the county child whose text content starts with

the letter K (using the starts-with(

) function). Both templates invoke the last template, which

matches county elements. Process

ri.xml with last.xsl like

this:

xalan -i 1 ri.xml last.xsl

Because an XSLT processor uses the last template when a match conflict arises, the stylesheet last.xsl produces this output:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<county state="Rhode Island">

<name>Kent</name>

</county>Only the state node containing

Kent is instantiated because that is what the last

template matching state instructed the processor

to do.

Tip

Notice that the encoding for the document is UTF-8

even though the source document has an encoding of

US-ASCII. To change the encoding

US-ASCII in the output, you’d

have to add an encoding attribute with a value of

US-ASCII to the output element.

Now in contrast, if you apply last.xsl to ri.xml with Instant Saxon, as follows:

saxon ri.xml last.xsl

you will see the following error report:

Recoverable error Ambiguous rule match for /state[1] Matches both "state" on line 14 of file:/C:/LearningXSLT/examples/ch08/last.xsl and "state" on line 10 of file:/C:/LearningXSLT/examples/ch08/last.xsl <?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?> <county state="Rhode Island"> <name>Kent</name> </county>

An XSLT processor is not required to report multiple templates matching one template rule, but processors may report such an error and may recover from the error. Either way, the processor must either stop or recover from the error by applying the last template that matches the rule. (See the last paragraph in Section 5.5 of the XSLT specification.)

The priority Attribute

Now compare last.xsl with priority.xsl , which is a very similar stylesheet shown in Example 10-3.

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0" xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform">

<xsl:output method="xml" indent="yes"/>

<xsl:template match="/">

<county state="{state/@name}">

<xsl:apply-templates select="state"/>

</county>

</xsl:template>

<xsl:template match="state" priority="2">

<xsl:apply-templates select="county"/>

</xsl:template>

<xsl:template match="state" priority="1">

<xsl:apply-templates select="county[starts-with(.,'K')]"/>

</xsl:template>

<xsl:template match="county">

<name><xsl:apply-templates/></name>

</xsl:template>

</xsl:stylesheet>The only difference between last.xsl and

priority.xsl is that the two templates matching

state elements each have

priority attributes. The

priority attribute can explicitly set which of two

or more conflicting templates gets used first. The higher the value

of the priority attribute, the higher the priority

of the template; in other words, a template with a priority of

2 trumps a template with a priority of

1.

When applied to ri.xml, priority.xsl produces the following output:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?> <county state="Rhode Island"> <name>Bristol</name> <name>Kent</name> <name>Newport</name> <name>Providence</name> <name>Washington</name> </county>

The template with a priority of 2 is invoked (the

first template of the two that matches state), but

the template with the priority of 1 is not.

Trivially, using the priority attribute can allow

you to switch templates on and off, which can be useful for testing.

More formally, however, the priority

attribute’s reason for being is to help distinguish

the patterns that match the same node but use different patterns.

Example 10-4, same.xsl, shows

you an example of this.

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0" xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform">

<xsl:output method="xml" indent="yes"/>

<xsl:template match="/">

<county state="{state/@name}">

<xsl:apply-templates select="state"/>

</county>

</xsl:template>

<xsl:template match="state">

<xsl:apply-templates select="county"/>

</xsl:template>

<xsl:template match="county[starts-with(.,'K')]">

<first-match><xsl:apply-templates/></first-match>

</xsl:template>

<xsl:template match="county[2]">

<last-match><xsl:apply-templates/></last-match>

</xsl:template>

<xsl:template match="county">

<name><xsl:apply-templates/></name>

</xsl:template>

</xsl:stylesheet>The template rule matching

county[starts-with(.,'K')] and the one matching

county[2] both match the same node

count, but each uses a different pattern (in that

each uses a different predicate) to identify the node. This results

in a recoverable error.

As with last.xsl, when ri.xml is processed with same.xsl:

xalan -i 1 ri.xml same.xsl

Xalan recovers from the error silently by using the last matching rule:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<county state="Rhode Island">

<name>Bristol</name>

<last-match>Kent</last-match>

<name>Newport</name>

<name>Providence</name>

<name>Washington</name>

</county>When ri.xml is processed with Instant Saxon, using:

saxon ri.xml same.xsl

it issues a warning about the error before recovering and using the last template rule:

Recoverable error

Ambiguous rule match for /state[1]/county[2]

Matches both "county[2]" on line 18 of file:/C:/LearningXSLT/examples/ch10/same.xsl

and "county[starts-with(.,'K')]" on line 14 of file:/C:/LearningXSLT/examples/ch10/same.xsl

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<county state="Rhode Island">

<name>Bristol</name>

<last-match>Kent</last-match>

<name>Newport</name>

<name>Providence</name>

<name>Washington</name>

</county>

prior.xsl, as shown in Example 10-5, changes the priority of these conflicting

rules by using the priority attribute.

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0" xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform">

<xsl:output method="xml" indent="yes"/>

<xsl:template match="/">

<county state="{state/@name}">

<xsl:apply-templates select="state"/>

</county>

</xsl:template>

<xsl:template match="state">

<xsl:apply-templates select="county"/>

</xsl:template>

<xsl:template match="county[starts-with(.,'K')]" priority="2">

<first-match><xsl:apply-templates/></first-match>

</xsl:template>

<xsl:template match="county[2]" priority="1">

<last-match><xsl:apply-templates/></last-match>

</xsl:template>

<xsl:template match="county">

<name><xsl:apply-templates/></name>

</xsl:template>

</xsl:stylesheet>Process it with:

saxon ri.xml prior.xsl

and the error is avoided:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<county state="Rhode Island">

<name>Bristol</name>

<first-match>Kent</first-match>

<name>Newport</name>

<name>Providence</name>

<name>Washington</name>

</county>The template matching county[starts-with(.,'K')]

is instantiated because it has a priority of

2 while the one matching

county[2] is not because it has a lower

priority value (1).

Another feature that affects template priority is import

precedence. Using the top-level XSLT element

import, you can import other stylesheets into a

given stylesheet. Import precedence is determined by the order in

which stylesheets are imported, which has an influence over template

priority. This topic is explored in Chapter 13.

Tip

The XSLT specification spells out the default priorities—what

template has priority over another by default with no

priority attribute—in Section 5.5. In

general, the more specific the pattern, the higher its priority. For

example, county[1] has a higher default priority

than county because it is more specific.

Calling a Named Template

It’s possible to have

templates in a stylesheet that don’t overtly match

any node pattern: you can invoke such templates by name. You assign a

template a name by giving it a

name attribute. In fact, if a

template

element does not use a

match attribute, it must have a

name attribute instead (though it is also

permissible for a template to have both match and

name attributes).

The call-template

instruction element has one required

attribute, also called name. The value of the

name attribute on a

call-template element must match the value of a

name attribute on a template

element. It’s an error to have more than one

template with the same name.

When you want to instantiate a named template, ring it up with a

call-template element. The advantage of calling

named templates is that you can instantiate them on demand rather

than only when a given pattern is encountered in a source tree. Also,

the context does not change when you call a template by name. Calling

a template is similar to calling a function or method in a

programming language such as C or Java, but without a return value.

Example 10-6 is a stylesheet that uses the

call-template element named

call.xsl

.

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0" xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform"> <xsl:output method="text"/> <xsl:template match="state"> Counties of <xsl:value-of select="@name"/>: <xsl:call-template name="nl"/> <xsl:apply-templates select="county"/> </xsl:template> <xsl:template match="county"> <xsl:text> - </xsl:text> <xsl:value-of select="."/> <xsl:call-template name="nl"/> </xsl:template> <xsl:template name="nl"> <xsl:text> </xsl:text> </xsl:template> </xsl:stylesheet>

In call.xsl, the template named

nl (short for newline)

contains a text element that holds a decimal

character reference for a single linefeed character

( ). The other two templates in the

stylesheet call the nl template to insert on

demand a single linefeed into the result tree. When applied to

ri.xml with:

xalan ri.xml call.xsl

this stylesheet produces:

Counties of Rhode Island: - Bristol - Kent - Newport - Providence - Washington

Using the name and match Attributes Together

A template

element can have both a

name and a match attribute at

the same time. This does not happen often, but you might want to do

this because you could instantiate a template upon finding a pattern,

or you could call the template when desired. I’ll

give you an example of how this works.

Look at the following similar XML documents in Examples 10-7 and 10-8. These documents show the estimated populations of the respective states, by county, as of July 1, 2001. (This information was garnered from the United States Census Bureau web site, http://www.census.gov.) The first is Example 10-7, delaware.xml .

<?xml version="1.0"?> <state name="Delaware"> <description>July 1, 2001 population estimates<description> <from>U.S. Census Bureau</from> <url>http://www.census.gov</url> <county name="Kent"> <population>129066</population> </county> <county name="New Castle"> <population>505829</population> </county> <county name="Sussex"> <population>161270</population> </county> </state>

The second document is rhodeisland.xml , shown in Example 10-8.

<?xml version="1.0"?> <state name="Rhode Island"> <description>July 1, 2001 population estimates<description> <from>U.S. Census Bureau</from> <url>http://www.census.gov</url> <county name="Bristol"> <population>51173</population> </county> <county name="Kent"> <population>169224</population> </county> <county name="Newport"> <population>85218</population> </county> <county name="Providence"> <population>627314</population> </county> <county name="Washington"> <population>125991</population> </county> </state>

The stylesheet in Example 10-9,

both.xsl, employs a template that uses both the

match and name attributes.

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0" xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform"> <xsl:output method="text"/> <xsl:template match="state"> <xsl:call-template name="nl"/> <xsl:text>Counties of </xsl:text> <xsl:value-of select="@name"/> <xsl:call-template name="nl"/> <xsl:text>Description: </xsl:text> <xsl:value-of select="description"/> <xsl:call-template name="nl"/> <xsl:text>Source: </xsl:text> <xsl:value-of select="from"/> <xsl:call-template name="nl"/> <xsl:text>URL: </xsl:text> <xsl:value-of select="url"/> <xsl:call-template name="nl"/> <xsl:apply-templates select="county"/> <xsl:text>Estimated state population: </xsl:text> <xsl:value-of select="sum(county/population)"/> <xsl:call-template name="nl"/> </xsl:template> <xsl:template match="county"> <xsl:text> - </xsl:text> <xsl:value-of select="@name"/> <xsl:text>: </xsl:text> <xsl:value-of select="population"/> <xsl:apply-templates select="population"/> </xsl:template> <xsl:template match="population" name="nl"> <xsl:text> </xsl:text> </xsl:template> </xsl:stylesheet>

This stylesheet creates a simple text report when used to process

documents such as delaware.xml and

rhodeisland.xml. As part of the report, it also

sums the content of population nodes using the

XPath function sum( ).

Like call.xsl, this stylesheet also has a

template named nl. The difference is that the

template also matches on population nodes. This

means that the template is invoked both when a

population element is processed (see

apply-templates in the template that matches

county) and directly by

call-template.

The following example processes delaware.xml and rhodeisland.xml with both.xsl using xsltproc, an XSLT processor written in C and based on the C libraries libxslt and libxml2. It runs in a Unix environment such as Linux or—as I use it—as part of Cygwin on Windows. This processor is available for download from http://xmlsoft.org or as part of the Cygwin distribution available at http://www.cygwin.com.

I’m showing you xsltproc because it allows you to process one or more XML documents against a stylesheet at one time. Here is the command line:

xsltproc both.xsl delaware.xml rhodeisland.xml

The stylesheet comes first, followed by a list of XML documents that you want to process. The outcome of this command is:

Counties of Delaware Description: July 1, 2001 population estimates Source: U.S. Census Bureau URL: http://www.census.gov - Kent: 129066 - New Castle: 505829 - Sussex: 161270 Estimated state population: 796165 Counties of Rhode Island Description: July 1, 2001 population estimates Source: U.S. Census Bureau URL: http://www.census.gov - Bristol: 51173 - Kent: 169224 - Newport: 85218 - Providence: 627314 - Washington: 125991 Estimated state population: 1058920

Looking back at the stylesheet, notice where the

nl template is invoked directly with multiple

instances of call-template. After the stylesheet

processes the name and population data of each county by invoking the

template that matches county nodes, it then

applies templates for population nodes, inserting

a linefeed after each node.

Using Templates with Parameters

For the purposes of XSLT, a

parameter is a name that can be bound to a value and then later

referenced by name. You learned about this in Chapter 7. You can use the

with-param

element as a child element of either

apply-templates or

call-template to pass a parameter into a template.

For example, a template could be invoked several times, each time

with a different parameter value, thus changing what happens when the

template is invoked. Watch what happens when a stylesheet calls a

template with four different parameter values.

Example 10-10, yukon.xml, lists cities in Canada’s Yukon Territory.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?> <province name="Yukon Territory"> <city>Beaver Creek</city> <city>Carcross</city> <city>Carmacks</city> <city>Dawson</city> <city>Faro</city> <city>Haines Junction</city> <city>Mayo</city> <city>Ross River</city> <city>Teslin</city> <city>Watson Lake</city> <city>Whitehorse</city> </province>

The stylesheet in Example 10-11,

yukon.xsl, processes

yukon.xml with each instance of

call-template passing a different value for the

parameter nl.

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0" xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform"> <xsl:output method="text"/> <xsl:template match="province"> <xsl:text>Yukon Territory Cities</xsl:text> <xsl:call-template name="nl"> <xsl:with-param name="nl" select="' '"/> </xsl:call-template> <xsl:apply-templates select="city"/> </xsl:template> <xsl:template match="city"> <xsl:text> -> </xsl:text> <xsl:value-of select="."/> <xsl:call-template name="nl"> <xsl:with-param name="nl" select="' '"/> </xsl:call-template> </xsl:template> <xsl:template match="city[.='Dawson']"> <xsl:text> -> </xsl:text> <xsl:value-of select="."/> <xsl:call-template name="nl"> <xsl:with-param name="nl" select="' (second largest city in the Yukon) '"/> </xsl:call-template> </xsl:template> <xsl:template match="city[.='Whitehorse']"> <xsl:text> -> </xsl:text> <xsl:value-of select="."/> <xsl:call-template name="nl"> <xsl:with-param name="nl" select="' (largest city in the Yukon) '"/> </xsl:call-template> </xsl:template> <xsl:template name="nl"> <xsl:param name="nl"/> <xsl:value-of select="$nl"/> </xsl:template> </xsl:stylesheet>

When you apply yukon.xsl to yukon.xml with:

xalan yukon.xml yukon.xsl

you produce this result:

Yukon Territory Cities -> Beaver Creek -> Carcross -> Carmacks -> Dawson (second largest city in the Yukon) -> Faro -> Haines Junction -> Mayo -> Ross River -> Teslin -> Watson Lake -> Whitehorse (largest city in the Yukon)

When the first template is invoked, it inserts the heading text

Yukon

Territory

Cities and then calls the template named

nl with the parameter nl

containing a value of two linefeed character references. (In XSLT,

there are no name conflicts between the names of templates and the

names of parameters or variables.)

As each instance of city is encountered in the

source, the stylesheet invokes the template that matches

city, each time with the parameter

nl containing only one linefeed. However, when

the stylesheet finds city nodes that contain the

text nodes Dawson or

Whitehorse, it calls the template with distinct

parameter values for nl—a line of text

followed by a linefeed.

You could produce the same results as yukon.xsl

without using with-param; however,

yukon.xsl illustrates how to use

with-param

. You can read more about

with-param in Section 11.6 of the XSLT

specification.

Tip

You can also use with-param as a child of

apply-templates, as demonstrated in the stylesheet

with-param.xsl, explained in Chapter 7. Nevertheless, with-param

is more commonly used with

call-template.

Modes

You already know what happens when more than one template matches an identical pattern—a conflict arises that may be overcome by template priority. There is also another workaround for template pattern conflicts: modes. Modes are useful when a stylesheet needs to visit a given node many times with varying results, such as when producing a table of contents or a list of authorities, to name a few examples.

The mode attribute is an optional attribute for

both the template and

apply-templates elements. If you modify these

elements each with a matching mode attribute and

value, you can match identical patterns with templates, without

generating an error. Following is an example of how it works.

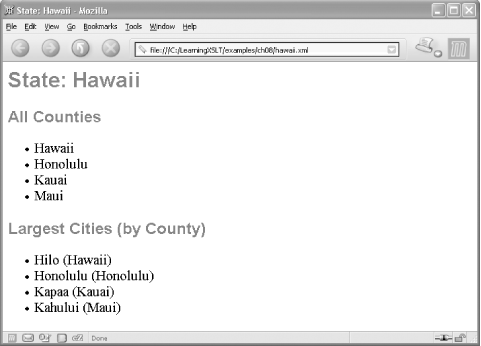

Example 10-12, the document hawaii.xml, lists each of the counties in the state of Hawaii in the U.S., along with the largest city in each county.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?> <?xml-stylesheet href="mode.xsl" type="text/xsl"?> <us> <state name="Hawaii"> <county name="Hawaii"> <city class="largest">Hilo</city> </county> <county name="Honolulu"> <city class="largest">Honolulu</city> </county> <county name="Kauai"> <city class="largest">Kapaa</city> </county> <county name="Maui"> <city class="largest">Kahului</city> </county> </state> </us>

Using an XML stylesheet PI, the document references the stylesheet mode.xsl, shown in Example 10-13, which produces HTML output.

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0" xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform">

<xsl:output method="html"/>

<xsl:template match="us/state">

<html>

<head>

<title>State: <xsl:value-of select="@name"/></title>

<style type="text/css">

h1, h2 {font-family: sans-serif;color: blue}

ul {font-size: 16pt}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<h1>State: <xsl:value-of select="@name"/></h1>

<h2>All Counties</h2>

<ul><xsl:apply-templates select="county" mode="county"/></ul>

<h2>Largest Cities (by County)</h2>

<ul><xsl:apply-templates select="county" mode="city"/></ul>

</body>

</html>

</xsl:template>

<xsl:template match="county" mode="county">

<li><xsl:value-of select="@name"/></li>

</xsl:template>

<xsl:template match="county" mode="city">

<li>

<xsl:value-of select="city"/> (<xsl:value-of select="@name"/>)

</li>

</xsl:template>

</xsl:stylesheet>There are two templates in this stylesheet that match

county elements. Because each of the two is

invoked in a different mode, no conflict occurs. In the first

template in the stylesheet, there are two instances of the

apply-templates element, each matching the

county pattern and each with a

mode attribute that has a unique value (one has a

value of county, the other

city). There are no name conflicts in XSLT between

the values of match and mode

attributes.

Later in the stylesheet, there are two templates that also have

mode attributes, matching the values used earlier

(county and city). In order to

work, the value of mode on a

template element must match the value of

mode in one or more instances of

apply-templates.

The outcome of applying mode.xsl to hawaii.xml in Mozilla is shown in Figure 10-1.

There are several paragraphs about modes in Section 5.7 of the XSLT specification.

Built-in Template Rules

XSLT processors have a feature known as built-in template rules . The built-in template rules were discussed in various places earlier in the book. Because of the built-in templates, an XSLT processor will process nodes in a source document, even though there are no explicit, matching template rules present in the stylesheet used to process the source document.

To illustrate how built-in templates work, here is a ridiculously simple example. The source document mammals.xml , shown in Example 10-14, lists a few mammals that are native to North America.

<?xml version="1.0"?> <mammals locale="North America"> <mammal>American Bison</mammal> <mammal>American black bear</mammal> <mammal>Bighorn sheep</mammal> <mammal>Bobcat</mammal> <mammal>Common gray fox</mammal> <mammal>Cougar</mammal> <mammal>Coyote</mammal> <mammal>Gray wolf</mammal> <mammal>Mule deer</mammal> <mammal>Pronghorn</mammal> <mammal>White-tailed deer</mammal> </mammals>

The rather boring stylesheet blank.xsl has only one line and no template rules:

<stylesheet version="1.0" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform"/>

When you process mammals.xml with this stylesheet:

xalan mammals.xml blank.xsl

Xalan finds no explicit templates for the element nodes in mammals.xml, so the built-in template rules kick in, producing the following result:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?> American Bison American black bear Bighorn sheep Bobcat Common gray fox Cougar Coyote Gray wolf Mule deer Pronghorn White-tailed deer

The built-in rules processed the root node, the element nodes, and all the text nodes that it found in mammals.xml. If you use an explicit template for just one of the nodes, that node will be processed with that template, but all the other nodes will be processed with the built-in templates.

The stylesheet

built-in.xsl

has only one template, and that template matches only one element

node, the sixth mammal child of

mammals, in mammals.xml:

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0" xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform">

<xsl:output method="text"/>

<xsl:template match="mammals/mammal[6]">

Found <xsl:value-of select="."/>!

</xsl:template>

</xsl:stylesheet>Process mammals.xml with built-in.xsl with:

xalan mammals.xml built-in.xsl

and you will get this output:

American Bison

American black bear

Bighorn sheep

Bobcat

Common gray fox

Found Cougar!

Coyote

Gray wolf

Mule deer

Pronghorn

White-tailed deerWhen the processor encounters the node pattern matched in the

template, it instantiates the template (including whitespace), but it

also applies the built-in rules. You can, in effect, shut off the

built-in rules by matching the unwanted nodes with an empty template

matching mammal, as does

shutoff.xsl

,

shown in Example 10-15.

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0" xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform">

<xsl:output method="text"/>

<xsl:template match="mammals">

<xsl:apply-templates select="mammal"/>

</xsl:template>

<xsl:template match="mammal"/>

<xsl:template match="mammal[6]">

Found <xsl:value-of select="."/>!

</xsl:template>

</xsl:stylesheet>When applied to mammals.xml:

xalan mammals.xml built-in.xsl

the result is just:

Found Cougar!

The difference is that when the processor encounters the first

template, it searches for all templates that match

mammal. Although both templates in the stylesheet

match mammal, they are distinct because only one

has a predicate that matches the sixth mammal node

and instantiates some literal text. The other template instructs the

processor to do nothing with all mammal nodes.

(This does not cause an error because the more specific template that

matches mammal[6] has priority over the template

that matches only mammal.)

Notice the difference in the final stylesheet in this section, cougar.xsl , shown in Example 10-16.

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0" xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform">

<xsl:output method="xml" indent="yes"/>

<xsl:template match="mammals">

<north.american>

<mammal>

<cat><xsl:apply-templates select="mammal[6]"/></cat>

</mammal>

</north.american>

</xsl:template>

</xsl:stylesheet>This single template processes the children of

mammals, but it selects only the sixth

mammal element, in document order, and discards

the others. When processed with mammals.xml,

like this:

xalan -i 1 mammals.xml cougar.xsl

you get the following result:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?> <north.american> <mammal> <cat>Cougar</cat> </mammal> </north.american>

I have mostly shown examples of the built-in rules working with element nodes, text nodes, and the root node. Table 10-1 summarizes what all the behaviors of the built-in template rules are when they encounter each of the seven nodes.

|

Node |

Behavior |

|

Root |

Processes all children |

|

Element |

Processes all children, including the text nodes; the built-in rule for text copies text through |

|

Attribute |

Copies text through |

|

Text |

Copies text through |

|

Comment |

Nothing |

|

Processing-instruction |

Nothing |

|

Namespace |

Nothing |

Section 5.8 of the XSLT specification discusses built-in template rules in greater detail. (Information on North American mammals was taken from the web site of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History at http://web6.si.edu/np_mammals/index.htm.)

Summary

You’ve discovered several new ways to use templates

in this chapter. You learned about template priority, how to call

named templates with call-template, and how to

call or apply templates with parameters. You also learned how to use

modes, and became more aware of built-in templates and what they do

in absence of working templates.

In the next chapter, you will learn what a key is, how to define keys

with the key element, and then how to process

those keys with the key( ) function.