CHAPTER FIFTEEN

Understanding the Implications of a Faulty Employee/Customer Paradigm—Or, Pissing Off the Customer Is a Real Bad Idea

Not long ago, I was coming back to Columbus on America West Airlines after making a speech in Boston. It was late and everybody was grumpy and fed up. Another lousy day of trying to make a living. But I’m talking about the America West cabin crew, not the passengers. The passengers were positively cheery by comparison.

The flight was way behind schedule, of course, and the crew had missed a meal break. They were unhappy and openly venting about how insensitive the airline was to their needs. “Bad day?” I asked one flight attendants who was moving down the aisle, doing her best not to make eye contact that might lead to a request for service. “Awful,” she said. And preceded to tell in detail just how awful it had been. “Funny,” I said when she paused for breath, “I was just reading an America West newspaper ad trumpeting a J.D. Power and Associates survey that designated the airline number one in short-haul frequent travel satisfaction.” The ad, I was informed, was a crock. And I don’t think she meant a crock of dry roasted peanuts.

For once, I held my tongue, which I’m not in the habit of doing when I am dealing with an airline, and customer satisfaction feedback is in order. There’s a United ticket clerk who may still be mulling over the lecture I gave her when she too informed me it was a bad day and, pointing to a nearby group of casually dressed passengers, said, “It really annoys me when tourists expect the same service as business travelers.” I won’t repeat the whole sermon, but I suggested that maybe they had every right to expect service and that perhaps they were hard-working business people who had earned frequent flyer points on her airline for their much-deserved vacations. “They may look like tourists, but they’re still customers,” I reminded her.

So the America West lady got off lightly, but I really should have told her that as a customer I didn’t care to hear about her grievances with her employer even though she may have had legitimate reasons to gripe. I sat there wondering if the pilot was also having a bad day.

I probably would have forgotten the story if I hadn’t experienced a sequel with a far different plotline involving Southwest Airlines. On a subsequent business trip, I was passing through the terminal in Columbus just after most of the outgoing flights had departed. I noticed that the Southwest counter was free of customers and that five clerks were standing there chatting. I couldn’t resist.

I walked over and said, “I’m writing a business book. I’ve been to seminars, read the case studies, and heard all about what a great company Southwest is to work for. I won’t use your names, but tell me—is it?”

In unison the five fairly shouted, “Yes!”

“Why?” I asked

“Because of Herb,” one of the men said, referring to Southwest’s CEO Herb Kelleher. They all nodded in agreement. In turn, the told me how “innovative” he was, “down to earth,” “fun,” and “terrific to work for.” All of them had been employed by other airlines and they contended that none even came close to Southwest as a great place to work. “We love it here,” one woman said, and told me that during the departure rush that had just concluded the airline employees at the adjoining counter had complained about the noise made by Southwest employees and their customers laughing and talking.

For the Red Notebook

Herb Kelleher thinks he’s CEO of Southwest Airlines, but he is actually its people czar. I’m naming my annual People Czar of the Year award “The Herb,” and the first recipient to mark the new century is—Herb.

Poor things! They had to listen to somebody having a good time. And I’m being only half sarcastic. It is too bad, and they’d be smart to shoot off a resume and a job application to Southwest to get in on the fun.

I could hear it at that Southwest counter: “TGIM—Thank God, it’s Monday. I can’t wait to go to work.” Every customer should cock an ear for the same solid-gold sound of satisfied employees. There isn’t a better way to determine whether or not you’re going to be satisfied with the product or the service. I hear it every time I walk into Starbuck’s and Office Max, for instance. The atmosphere is bright and upbeat. There’s almost a hum of electricity. It says to the customer that something special is happening: I’m having a good experience working here, and you’11 have a good experience shopping here.

Value Delivers Value

When Roger Gittines and I were outlining this book, he asked me what I planned to write about customer satisfaction. “The whole book is about customer satisfaction,” I said. And it is.

It is nearly impossible to consistently deliver value to the customer if the employee is not deriving meaningful value from the work experience. In their book, First, Break All The Rules: What the World’s Greatest Managers Do Differently, Marcus Buckingham and Curt Coffman report on a 1997 survey of employee satisfaction at a national chain of three hundred retail stores. The results were tallied up and compared store to store, and then tracked against profits at each outlet. Those in the top 25 percent of the survey ended the year 14 percent higher than the targeted figure in the individual store’s budget. Those who finished in the bottom 25 percent undershot their profit target by 30 percent. Even more startling, the employee retention ratio between the two groups was such that in total those in the bottom 25 percent lost a thousand more employees than did the top 25 percent. The wasted training costs came out to almost $30 million.

Buckingham and Coffman conclude that the disparity was caused by an inconsistent culture, but that the good news was the company was “blessed with truly exemplary managers” in the stores that turned in high employee satisfaction numbers:

These managers had built productive businesses by engaging the talents and passions of their people. In their quest to attract productive employees, the company could…find out what their newly highlighted cadre of brilliant managers was doing and then build their company culture around this blueprint.1

Rewind: “engaging the talents and passions of their people.” I couldn’t have said it any better myself.

A Little Dissatisfaction Goes a Long Way

There is a formula that estimates that every disgruntled customer tells an average of twelve other people about the experience. That’s a lot of damage for starters. But if I had an employee dissatisfaction problem among my two thousand person salesforce to the tune of just 10 percent, with each of them contacting five customers a day, the damage potential would be hair-raising. Do the numbers: Two thousand reps, with a 10 percent dissatisfaction rate, contacting five customers each day over a five-day work week could directly sour five thousand customers, who then spread the word to sixty thousand others. That’s just one week! If the malcontents were as eloquent as the America West flight attendant, and if they gave each of five customers a day as negative an experience, we’d be looking at nearly a quarter million people who have gained a poor opinion of the operation a month. Next month it could another 240,000, and on, and on, and on until my administrative assistant buzzes me:

“Frank, your mother called.”

“Put her through.”

“No, she hung up after telling me how much she hates our company.”

In reality, those numbers wouldn’t accumulate as rapidly. Word of mouth spreads slowly and the negative impact dissipates as it moves away from the original dissatisfied customer. But it’s interesting to note, in 1994, Southwest Airlines estimated that just five customers per flight—3 million out of a total of 40 million customers—meant the difference between profit and loss for the company. Consider how much daily customer contact a single flight attendant has. Somebody like Ms. Sunshine at America West would have single-handedly put Southwest into chapter eleven. Pissing off the customer is a real bad idea.2

Sarcom’s Peter Rogers told me that his company’s policy on customer satisfaction is that “everyone owns the account.” That makes sense as insurance against handcuffing a valuable customer to someone who might be having too many bad days in a row. But the best insurance of all is to stay on top of employee satisfaction.

You don’t really need to pay for formal surveys. Keep asking them how they feel about their job. Listen and take action to correct the problems. Buckingham and Coffman—they are part of the Gallup organization—asked twelve good questions in their survey. You might take a look at their book for the wording. But I’ll give you a one question survey to be answered with one word followed by a brief essay.

Is this company a great place to work?

Yes or no. Please explain why.

Taking a Meter Reading

When I did my interviews of the coaching staff at the University of Dayton, I kept hearing the same two phrases over and over again—“there are no limits” and “there is no ceiling.” Limitless opportunity is a powerful employee satisfier. Jane Fichem, vice president for human resource development at Bass Hotels and Resorts says that, in general, lack of opportunity is one of the most frequently cited reasons that employees give for leaving their jobs and going elsewhere.3

And here’s a good survey question: “Are you satisfied with the opportunities for advancement and career development that we offer in this company?” In addition, another couple of questions occurred to me during my conversation with Jane Fichum, who reported that the principal complaint from those who quit is, “I didn’t get any feedback on how I was doing. My boss never established what I was expected of me.” You’re probably already writing the questions in your red notebook:

- Are you satisfied that your manager has told you explicitly what he or she expects from you?

- Are you satisfied with the amount of feedback you are receiving on your job performance?

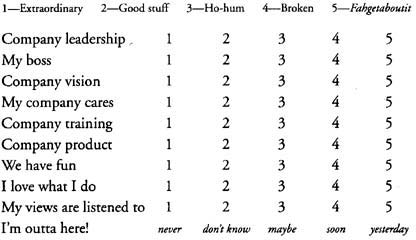

If you combine these questions with the Pride Quotient Test in chapter 3, it will make for an effective survey. Or use the ho-hum meter:

TO: All Employees

SUBJECT: Employee satisfaction, the Ho-Hum Meter

Please fill out the following chart, circling 1 to 5. No names. No repercussions.

Anything that draws threes, fours, and fives from more than 10 percent of the workforce is a barrier that needs to be cut down immediately. Then, start delivering the message: “There are no limits.”

Staying out of the Penalty Box

If you are a manager, try this. Choose the name of someone who works for you. Go the file and pull out his or her personal development plan. You’ve got two minutes. I’ll wait.

Doc P’s Truth Serum is served. Did you not bother to get up and look in the file because you knew that a personal career development plan wouldn’t be there? Or did you look and come up blank?

Now-To

Work with each team member to draft a personal career development plan.

Or, if there are plans on file, review them, evaluate progress to date, and update them.

If there are no plans on file or the ones that are there are outdated, the penalty is that you’re going to have to go back and reread the book from the beginning. People-ology is not breaking out all over. Among other things, there is a fundamental communications problem. People are not being asked what they want and expect from the relationship. Or if they are being asked, nobody’s listening and helping them to achieve their dreams. The highlights of a personal career development should be part of the employee performance contract that is reviewed monthly.

Say it—“Monthly.”

I know: There’s no time. But the time you save by escaping from the misunderstandings and lack of productivity that comes from not doing monthly reviews will more than cover the initial squeeze that you may feel.

Back up the contract up with a second, more detailed document that will take an employee five, ten, or even twenty years into his or her career. I’m not so sure that the conventional wisdom is so wonderful that we’ve got to get used to being job-hoppers. If it’s truly a great place to work, I want my gold watch, thank you.

Now-To

Establish career development plans for all your people.

Encouraging Mentor Mania

Mentors are another antidote to employee dissatisfaction. It’s better to have a unhappy team member crying on a mentors shoulder than venting with a customer. Mentors offer solace, support, second opinions, and kicks in the butt when necessary. And that last function is an important one. Sometimes it’s the only way to learn. Coaching is fine, and I’m all for consensus building and the Socratic method, but sometimes more forceful communications techniques are required.

Bill Duffy, remember him? He was my football coach at Brooklyn Prep. One day at J.V. practice I was particularly inept. Inept? I was horrible. We were running our pass offense against the second team’s defense. I was throwing interception after interception. After each play, the quarterback was supposed to leave the huddle and consult with the coach about what would happen next. Coach Duffy would patiently explain what I was doing wrong. After several more interceptions, and as I turned to go back to talk to him, Coach Duffy yelled, “Don’t turn around, Frank. Stay right there. Don’t talk to me. You stink!” Reflexively, I kept turning toward him. “No, you stink. Stay there. I don’t want to talk to you.” The other kids in the huddle had all they could do to keep from laughing out loud.

My game instantly improved a thousand percent.

I call this the “Needle.” Leaders have to be willing to use the needle when all else fails, but use it judiciously, deliberately, and without intended malice. Also, as much as a I loved Coach Duffy, use the needle one-on-one so as not to embarrass anyone publicly. Or, use it in a group setting without aiming it an individual.

Example: “Fred, five years ago you would have had this done by now. I think you’re slowing down. But that’s okay, it happens to the best of us.”

Fred will be hugely miffed. And the deal will get wrapped up in a flash.

Example: “I brought this with me today (hold up a gas can)—this team is running on empty.”

The team will be hugely miffed. And their energy levels will zoom.

Example: “Frank, are you going to give us the same old shtick today?”

When Ron Nelson, one of my managers, needled me that way prior to a team meeting he had asked me to address, I responded by delivering a exhortation that made Gen. George Patton and Shakespeare’s Henry V seem like tongue-tied wimps—or so it seems to me upon modest reflection.

Most people know when they’re being needled and don’t let it bother them deeply. But there’s enough of a jab to motivate.

Even the golf pro at my country club uses the needle. We were out one day working on my hopeless swing and testing the new set of clubs he had sold me. It was hot, we were sweating, and I was not making progress. If anything, I was getting worse, not better. “It’s this new driver,” I said lamely.

That did it. Vic crossed his arms and stood back. “No, Frank, your problem is loft,” he snapped.

“Loft?”

“Yeah, L-O-F-T: Lack of F—ing Talent.”

That hurt! But in this case, the needle hasn’t worked yet. When it comes to golf, loft is still a problem. But every time I tee up, I hear Vic say, “Frank, your problem is loft,” and I try my damnedest to hit the ball long and straight.

Finding the Missing Message

There is something missing in this chapter on employee satisfaction and how it impacts on the customer. I wonder what it is? Help me with this. We’ve been working on pride and passion and talent. No problem there. The ho-hum meter goes after vision, training, caring, and so on. Manager mistakes—that’s taken care of. Career development is covered. Buckingham and Coffman’s survey even asked if the employee has a best friend at work. Good idea. What’s missing?

From somewhere just south of Yipsalanti, Michigan, I can detect the distant sound of a reader screaming. “Money, you idiot!”

Oh, yeah. Money. Like sex, we think about money all the time but don’t like to admit it out loud.

Stop Whining—and Start Winning’s dirty secret about money is that you get what you pay for. I’m sorry that it comes in the form of such a clanking cliché, but those are the breaks. Every dollar that is paid in the form of compensation bears a message in addition to “In God We Trust.” Usually it’s not just one but several messages, ranging from “We expect you to show up for work at nine o’clock in the morning,” “Be part of the team,” “Make Mr. and Mrs. Bliven very, very pleased to be doing business with us” to “By the way don’t screw up.”

There’s nothing wrong with those four messages, but 44 messages, or 444, get to be a problem. Which one is the most important? Where do I start? In what order do I tackle them? There is message overload; we don’t know what we’re getting paid to do. And it makes for a lot of conscious or unconscious dissatisfaction.

The quickest and easiest way to sort this out is to hire a consulting group. Most of us have horror stories about consultants, and so do I. But with a well-defined mission and careful controls and inspection, consultants can bring value to the table. I found that to be the case with the Alexander Group, a business consulting firm that specializes in compensation plans. I know it sounds like a advertisement that’s out of place in a book dedicated to a balanced, unbiased, and unopinionated presentation of scholarly research—and it would be in a book of that sort. My mission is to tell you about what works. These guys work. I’ve hired the Alexander Group in the past and the firm did a great job of helping design a world-class compensation package.

One reason for my high customer satisfaction was consultant Mark Donnolo. He’s the one who explained to me how important it is to identify and deliver the message that is explicitly and implicitly part of compensation. Donnolo does a lot of work with sales organizations that tend to use some form of a variable-pay plan—that is, sales commissions. But I think variable-plans—bonuses and incentives—are the only way to go for business organizations. Hell, any organization, for that matter. Pay the priest or preacher based on how he’s managed to increase the size of the congregation, and the school principal according to how test scores have improved.

And that’s what I think Donnolo means by a message. What do I expect? How much is it worth? How much do I pay to get it? Who do I pay to deliver it? Answer those four questions and you are on the way to having a message. You’re not quite there yet, though. Before you pay, you have to ensure that the organization can play.

“You can’t do compensation,” Donnolo says, “if you don’t have the organization designed correctly. So if you have a flawed sales operation in terms of how it’s designed and how it aligns to the markets, the compensation plan is not going to work correctly. You’ve got to understand the job, and you’ve got to understand their objectives first of all.”

I get it. “You, you, and you go sell this stuff” is not much of a message and not much of organizational design. What I also got from Mark Donnolo is confirmation that structuring compensation requires rigorous analysis before the package is finalized and while it’s in service. This is not a subject that can be handled casually or in a one-size-fits-all manner.

It comes down to the questions I’ve asked again and again throughout the book:

- What do we want?

- What do we do to get it?

- How do we know that we’re getting it?

The compensation message and the message have to align. If 100 percent employee/customer satisfaction is the message that has to be translated into dollar terms in the compensation plan in order for the two messages to square up. You pay for what you get.

Mark Donnollo says it without resorting to a single cliché:

You’ve got to keep the message very simple because the reason you design a compensation plan is that a variable-pay plan is not intended to pay people lots of money. It is because you want to communicate a message. And if you don’t want to communicate a message, you’d probably just pay them base salary because it’s a lot simpler to administer. But if you’re going to have pay-for-performance, you want to keep the message very clear. So you want to say go out and sell, get revenue, or get profitability, or sell certain products, or sell to certain markets.4

My reading of this is that too many companies don’t know what message they’re sending with compensation, and if they did know it would turn out to be a garbled contradictory message that undercuts the results and hurts employee moral.

“Don’t ask for one thing, and pay me for another” is the lament. Or, “If it is so damned important, why aren’t they paying me for it?”

Now-To

Find out what you’re paying for. What’s the money message that’s being sent?

Pay for what you want. Pay for what you get. But this doesn’t mean to serve what Donnolo calls a “buffet” of compensation: Do this for $1,000 extra, do that for $500, maybe this for $1,500…that’ll take too long. I’ll go for $500, it’s quicker and easier. Incentives must be focused and significant in terms of what they contribute to the individual’s overall income.

Another key point: The size of the incentive must relate to how much influence the person has on the objective. Don’t load people up with incentives that they have no way of earning. Conversely, withholding incentives from someone who’s in a position to directly achieve the desired outcome is also foolish. In sales, management is often fond of imposing “top stops,” which curtail commissions once they hit a certain amount. To me, top stops are insane. What’s the message? Stop selling. And the response from the sales team is, “Top stop? I will stop.”

The playwright George Bernard Shaw said, “Lack of money is the root of all evil.” I say, lack of a smart money message is a dumb way to do business.

Compensating a Soccer Dad

In the final analysis, employee satisfaction is all about compensation. Southwest Airlines issues two kinds of paychecks, one that can be taken to the bank and cashed, and another that comes in the form of pride and professional respect. Effective leaders recognize the need for both. Maybe I sound naive—but I’ll risk it: Money, no matter how much of it there is, never compensates and never fills the void that’s left when prides dies.

My daughter gets the last word on satisfaction and compensation in this chapter. The two of us were on our way to a soccer game one Saturday morning. Alle was in the middle of the backseat. Sports is not one of her big things, but she’s fast on her feet and well coordinated. I was giving her coaching about how to handle the game, stuff like “stay on the ball” and “keep your head up.” Advice Manchester United would pay me big bucks to deliver to their stars. I was rattling on the way I do with her brother before a big game until I heard a sigh. “Dad,” I looked into the rearview mirror that framed her gorgeous eyes, “you know, it’s really not that big a deal.”

She was right. Racking up the points, going for the numbers isn’t such a big deal. I took a deep breath, exhaled slowly, and took another look at the mirror to admire those bright eyes again, and felt very satisfied indeed.