CHAPTER 5

Sales Activities—the Drivers of Sales Performance

THE MISSING METRICS ON THE WALL

As the 306 metrics slowly found their rightful places on our own war room wall, we were eventually left with only the numbers that can truly be managed. Of course, these were measures of Sales Activities. Compared to Business Results or Sales Objectives, these metrics are extremely cooperative because they measure the things that a sales force actually does. Pursuing leads, planning for sales calls, visiting prospects, strategizing opportunities, and managing customer relationships are the day-to-day activities that are done in pursuit of Sales Objectives and Business Results. Perform these tasks efficiently and effectively, and achieving your quota is a breeze. Fumble around and misplace your effort, and any goal feels like a stretch. Plainly stated, these things are important.

Imagine our disappointment, then, to find that more than 80% of our 306 numbers were already pinned to other walls. That means that only 17% of the metrics in our study were intended to measure the Sales Activities that actually determine sales success or failure. So while these activities are critically important to every organization, it appears that measuring the quality and quantity of them is not.

Let us reiterate that these are all of the things that a sales force actually does. No one “does” revenue or product mix, but everyone makes sales calls. All of what the sales force does resides in this bucket, yet more than 80% of what management chooses to measure resides elsewhere. Hmm. If a goal of management is to gain greater control over sales force behaviors, then it would seem we had uncovered a very large problem.

You’ve probably heard the old management adage that “what gets measured gets done.” Ironically, it appears that in most sales forces, what gets done doesn’t get measured. As you might expect, we’ve questioned many sales leaders over the years on why this is the case, and there are two primary reasons that they typically offer in response. One concerns their ability to collect credible data, and another regards their desire to use it. While we can appreciate their objections, we find that they both are fading in relevance.

The first objection we encounter when we push clients to report more Sales Activity metrics is that activity-level data is difficult to collect, and this is somewhat true. While information such as a customer’s purchasing history can be easily extracted from a company’s financial reporting system, information about a sales rep’s activities typically cannot. Capturing this type of data often requires some manual intervention, including the need for reps to enter information themselves.

Not only do many managers not want their reps spending time on data entry, nearly as many will tell you that they don’t trust the information that their sales reps provide. To us, these arguments are remnants of a bygone era when information technology was not pervasive and salespeople were lone rangers. When we hear sales reps ask, “Would you rather me be in front of a computer or in front of a customer?” we respond, “Both.” And when we hear a manager say, “My reps just lie about their call volumes when they put them into the system,” we say, “Then fire them.” In the twenty-first century, people interact with electronic devices constantly, and salespeople are expected to be professionals. If management wants activity-level data to help it manage its sales force, then it needs to set the expectation and then make it happen. We work with many organizations where this is the case, and they have better managers because of it.

The second objection that we often hear is that managers don’t even want activity-level data on their salespeople. Here, the argument goes that they don’t wish to give the appearance of micromanaging their sellers. A curious instance of this sentiment occurred several years ago when we were researching the sales management practices of several top sales forces in the United States.1 One head of sales explained to us quite apologetically that his company regretfully collected and reported activity-level metrics. He confided, “Yeah, we do collect a lot of data on our salespeople’s activities. I guess we’re just kind of old-school in that way.”

We would contend that collecting activity-level metrics is not old-school whatsoever—we think it is new school. And we would argue that tracking salespeople’s activities won’t lead to micro-management—it will lead to proactive management. Technology has enabled us to collect these metrics in less intrusive ways, and our new sales management framework will enable us to use the data in a more sophisticated manner. Going forward, we hope that all war room walls will have a fair representation of Sales Activity metrics, since managing those numbers is what aligns sales force behaviors with desired outcomes. Whether old or new, that’s the school for us.

SALES PROCESSES, YOU SAY?

Clearly we believe that measuring Sales Activities is a key ingredient to better sales management. However, reporting data on salespeople’s doings is not sufficient to exercise control over a sales force’s performance. To truly exert influence over Sales Objectives and Business Results, sales managers must not only receive relevant data, they must know what to do with it. They therefore need a way to organize a sales force’s activities into a coherent operating system with predictable inputs and outputs. They need a set of formal business processes.

As we discussed earlier in this book, other business functions like manufacturing or finance are typically managed with a higher level of rigor than the sales force. In large part, this is because other corporate functions have formal business processes in place that allow for consistent execution and robust measurement of their daily activities. This visibility into the gears and pulleys of a workforce is required in order to exercise control and continuously improve. In the absence of standardized processes to enable active management, sales leadership often finds itself in the war room attempting to herd cats rather than direct soldiers. Sales managers have unmanageable chaos rather than command over their troops.

This point was colorfully illustrated by a conversation we once had with a senior executive of a $400 million software company whose revenues had stalled. He was frustrated by his company’s inability to improve its sales force’s productivity, so he approached us for advice. Our initial conversation contained an exchange that went something like this:

Vantage Point Performance: So you have a little more than 250 salespeople in the field?

Discouraged Senior Executive: That’s right.

VPP: And what exactly do they do?

Executive: They find new customers for our software.

VPP: How do they find new customers?

Executive: You know. They prospect in their territories and then try to close whatever deals that they uncover.

VPP: And how do they do that? I’m trying to understand the processes they follow, so I can get a better sense of where the problem might be.

Executive: I don’t know what processes they follow—you’d have to ask them.

VPP: You don’t have any kind of standard sales processes for your sales force to follow?

Executive: No. It’s up to the salespeople to find new business any way they can. That’s their job.

(Pause)

VPP: So you have 250 people in the field selling in potentially 250 different ways?

Executive: Potentially, yes.

VPP: How different are the customers they sell to? Do they all buy from you in a similar way?

Executive: Sure. Given the technical nature of our products, we end up selling to pretty much the same type of customer. Their buying patterns are probably very similar.

VPP: So do you think there might be a “best” way to go about selling to those customers?

Executive: I’m sure there is, but I don’t know what it would be. That’s why we have the sales force … to figure that out.

VPP: Well, OK, but if you have no standard sales process, then how can you measure how successful your salespeople are at doing whatever it is that they do?

Executive: Well, of course, we know how much they each sell.

But that’s about it.

VPP: How long is the average sales cycle?

Executive: Around six months or so, on average.

VPP: And you don’t measure anything that they do for the six months leading up to a sale?

Executive: No, not that I’m aware of.

(Longer pause)

VPP: So, you have 250 salespeople, with no formal sales process, doing something (you don’t know what) to your customers over a six-month period, and you have no metrics to track and improve the effectiveness of their selling activities?

Executive: That pretty much sums it up. I’m sensing from your question that you think that’s a problem?

VPP: Well, if your burning issue is an inability to proactively improve your sales force’s performance, I’d say that is the problem.

Executive: Hmm. I’ve never really thought of it that way. You’re probably onto something, though.

Like many, this senior executive knew very little about what his sales force actually did from day to day. His VP of sales had to-date employed the management-by-results approach of offering his sales reps very high commissions and then “getting out of the way to let them do their job.” Unfortunately, that strategy backfired when revenue growth slowed. Without formal sales processes and measurements in place, he had little visibility into his sales force’s activities and even less control over them. It is a very frustrating place for an executive to be.

This conversation took place many years ago, and most sales leaders today know that formal sales processes are required for effective management. However, the term sales process is still a very murky concept for most. During our careers, we have heard the term sales process used in as many different ways as one can imagine. And that single fact points to a fundamental challenge of controlling sales performance: we don’t have a common framework or a common language to manage the Sales Activities that drive sales performance. We need a better understanding of the fundamental business processes that are at work within every sales force.

It’s worth noting that several people advised us during the writing of this book not to use the term sales process. They warned that process is a dangerous word that could confuse readers, since each company defines its sales processes in its own way. And that is the precise reason that this book is needed. Every sales force should customize its sales processes to the way it does business, but it should not be responsible for defining what sales processes are. There should be a common discipline within the field of sales for how things work. Further, that discipline should be taught to sales managers just like generally accepted accounting principles are taught to accountants and total quality management is taught to engineers. Without it, sales managers are forced to make it up as they go along. Every single time.

Therefore, we felt that to truly crack the sales management code, we had to wrestle this issue to the ground. It was not enough to merely identify that Sales Activities are the most basic levers for controlling a sales force—we had to discover how those levers fit into manageable sales processes. We had to figure out how sales managers could organize and direct their sales-people’s activities to predictably influence all the other metrics on the wall. If we could do that, we would have done something meaningful. If not, the sales force would remain a collection of seemingly unrelated activities, and the chaos would persist.

THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF CONTROL

We braced ourselves for the expectedly arduous task of definitively identifying the fundamental processes at work in every sales force. Given the fact that it had never been done before, we assumed that we would struggle mightily to tease out distinct sales processes that would encompass all of the remaining metrics on our wall. Surprisingly, the task proved to be quite easy.

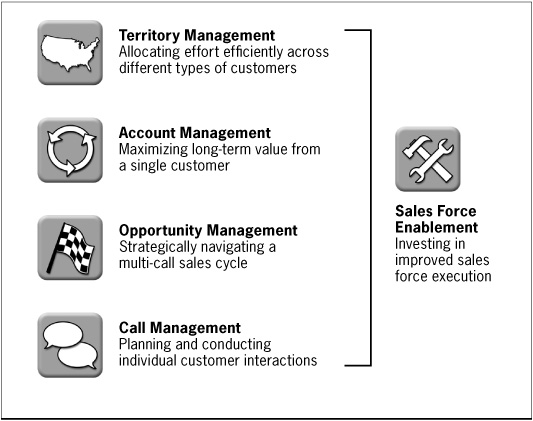

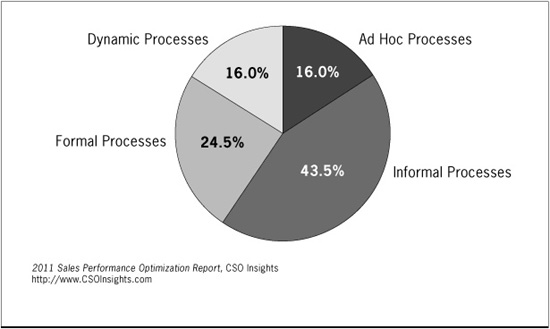

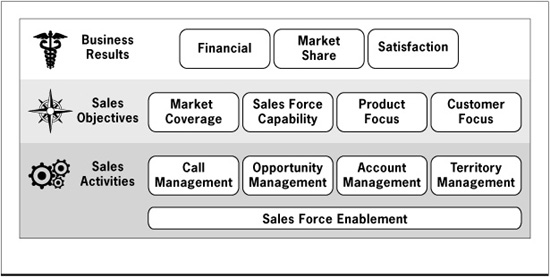

Each of these remaining metrics was collected by sales management to make sure that some type of selling activity was taking place. And if the activities were important enough to measure, then each of them most certainly pointed toward the achievement of a very specific goal. Therefore, to identify the nature of each specific sales process, we simply had to determine the desired outcome of each activity. Within minutes, we had shuffled the remaining numbers on our wall into five separate processes—four for the sales rep’s activities and one for sales management’s (see Figure 5.1). We had extracted from the metrics the fundamental building blocks for gaining control over a sales force. The code had finally cracked, and we were on the cusp of mapping once and for all the sales force’s DNA.

FIGURE 5.1 Building Blocks of Control over Sales Performance: The Fundamental Sales Processes

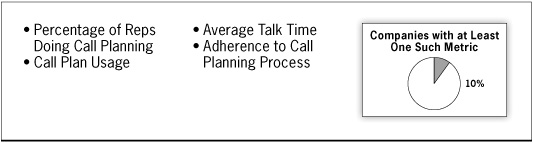

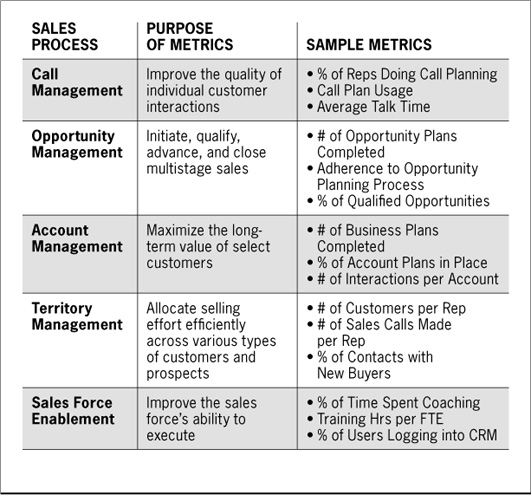

First, we found measures of activity that were directed toward effective Call Management. These metrics, such as Percentage of Reps Doing Call Planning and Call Plan Usage, are intended to ensure that sales calls or meetings are conducted effectively. In our study, navigating an individual sales call was the most elemental form of sales process.

If you string together several sales calls in pursuit of a single deal, then you will need to employ the second type of sales process we observed, Opportunity Management. Metrics that measure Opportunity Management, such as Opportunity Plan Usage or Adherence to Opportunity Planning Process, make certain that salespeople are thoughtfully pursuing individual deals.

If you find that you are pursuing multiple deals over time with a single customer, then you might choose to engage in our third sales process, Account Management. Account Management metrics such as Percentage of Account Plans Complete or Number of Interactions per Account measure the sales rep’s effort in retaining and growing existing customer relationships.

And finally for the salesperson, if you target many customers and have to allocate your time efficiently across them, then you are engaging in Territory Management. Measures such as Number of Calls Made or Number of Meetings per Customer Type track sellers’ efforts to call on the right customers in the right quantity.

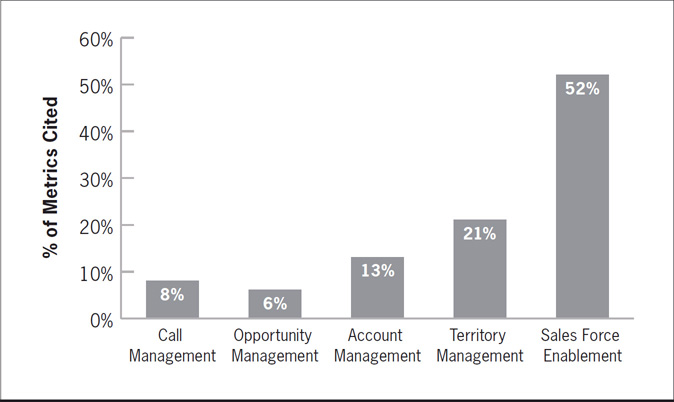

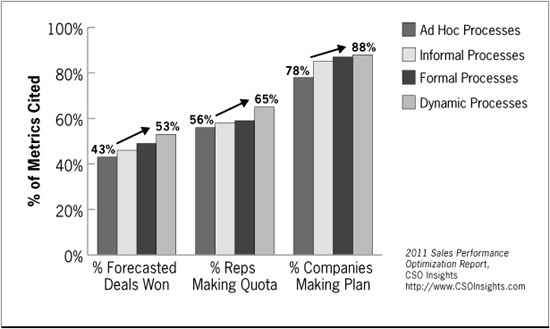

We also found several types of metrics that were used to gauge how well sales management is preparing its sales force to succeed. We called them collectively the Sales Force Enablement process, and they include numbers such as Percentage of Time Spent Coaching and Training Investment per FTE.2 These varied measures help to focus sales management on developing and supporting the capabilities of its sellers. Sales Force Enablement metrics were by far the most common Sales Activity measure found in our study (see Figure 5.2).

FIGURE 5.2 Prevalence of Sales Activities by Process

Remarkably, all of the Sales Activity metrics on our wall fell neatly into one of these five sales processes. When we stepped back and looked at the categories we had formed, we marveled at the simplicity. These truly are the most fundamental things that a salesperson does: make sales calls to win opportunities to gain customers within their territories. And sales managers enable those efforts by equipping and developing their sellers. That’s it, the skeleton of a sales force. A marvel of simplicity.

Sure, there’s plenty of other stuff going on in the sales force, but these are the fundamentals, the basic processes that drive sales performance. By pushing and prodding these five sets of activities, sales leaders can influence all of the higher-level metrics in our sales management framework. These are the numbers that can be changed at will by sales managers, and doing so gives them the power to accomplish any Sales Objective or Business Result they desire. These five processes are the building blocks of control over a sales force.

Just like “discovering” that you can’t manage revenue, this discovery was a bit of a brick-meet-forehead moment. Of course this is what the sales force is trying to do. Of course these are the things we should measure if we want to proactively manage a sales force’s performance. But then again, if it’s so obvious, why weren’t there more of these metrics on our wall?

Despite the relative scarcity of Sales Activity metrics in our study, these five processes are the levers and pulleys that control a sales force. They are essential mechanisms of sales management. So we will spend a good deal of time exploring the five processes that encompass our Sales Activities. We will also share observations on the metrics, tools, and common issues that typically relate to each.

To sales force generals, this chapter might seem a little like boot camp. These are the fundamentals of hand-to-hand combat, and any experienced salesperson has participated in all of these processes to some degree. However, gaining a crisp and comprehensive understanding of each will enable you to direct the battles on the field with greater insight and impact. After we detail these final pieces of sales management code, we will explore how to assemble a unique management system to decorate your own war room walls.

Call Management

![]() No doubt, making sales calls is the most essential task of the salesperson. Whether face-to-face, over the telephone, or even through some electronic means, direct interactions between a seller and a buyer are at the core of every salesperson’s role. For that matter, they are the very reason that a company needs a sales force. If an organization made no sales calls, it would need no salespeople. So if a company has a sales force, you can bet it’s making calls.

No doubt, making sales calls is the most essential task of the salesperson. Whether face-to-face, over the telephone, or even through some electronic means, direct interactions between a seller and a buyer are at the core of every salesperson’s role. For that matter, they are the very reason that a company needs a sales force. If an organization made no sales calls, it would need no salespeople. So if a company has a sales force, you can bet it’s making calls.

The nature of a sales call can vary greatly, though, ranging from an inbound phone call to an off-site customer retreat. The frequency of sales calls can also vary wildly—a retail sales rep may participate in dozens of “calls” each day, while a strategic account manager may only make a dozen face-to-face sales calls in a year. Regardless of the nature or frequency, the quality of the seller-buyer interaction will determine whether or not a sale is made. Do the right things during a sales call, and the sale will move forward. Do the wrong things, and the sale will come to an abrupt and unwelcomed end. Therefore, companies often engage in activities to improve the quality of their sales calls. These activities comprise a Call Management process.

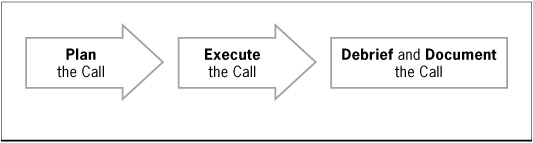

The Activities. Call Management is a vital process for many salespeople. Of course, managing a sales call really comes down to careful planning, execution, and reflection on the part of the seller, and sales managers can play a very valuable role in helping their salespeople navigate these elemental sales activities. Unfortunately, managers cannot manage the outcomes of a call—successful call outcomes are Sales Objectives, since they require agreement from the buyer. But a sales manager can heavily influence the outcomes of sales calls by guiding the salesperson through the process.

Foremost in the process, sales reps must prepare for the call. A thorough call-planning exercise forces salespeople to set clear objectives for the call, plan what they intend to do, anticipate what the buyer might do in response, and identify alternative actions in case things deviate from the plan. This straightforward activity can have a dramatic impact on the quality of the sales call and the likelihood of a successful outcome.

Second, salespeople must execute the call. This is the main event of selling. While there are many factors that affect the ultimate outcome of a sale, nothing is more significant than a seller’s direct interactions with the buyer. This is the salesperson’s best chance to uncover key information and to influence the buyer’s thinking in a robust, iterative dialogue. During every call, a seller can dramatically improve or decrease her likelihood of winning the deal. This is why thorough call preparation is so very important. You’ve got to know what you’re doing. See Figure 5.3.

FIGURE 5.3 A Basic Call Management Process

This brings us to the final Call Management activity, which is to debrief the call. During a post-call debriefing session, the sales manager and rep document the call outcomes and discuss the good, bad, and ugly of what took place. Whether or not he accompanied his salesperson on the call, the manager should help the seller reflect on her own performance and critically evaluate her decisions and actions. A call debrief can be one of the most powerful developmental activities for a salesperson, particularly under the guidance of a skilled coach.

The Metrics. Most of the Call Management metrics we observed were focused on pre-call planning activities. Commonly, these are measures that track whether salespeople are adhering to a call planning methodology or using their call planning tools. In our study, we observed a handful of these measures, like Adherence to Call Planning Process and Call Plan Usage (see Figure 5.4). These metrics can be collected in a variety of ways, including sales force surveys, sales manager observations, and reports that are generated from the planning tools themselves.

FIGURE 5.4 ![]() Sales Activity Metrics in Our Study: Call Management

Sales Activity Metrics in Our Study: Call Management

It is possible to track performance in the other stages of the Call Management process, too. In-call metrics might include Number of Questions Asked, Sales Rep Talk Time, or other measures of salesperson behavior during the call. Metrics such as these are best obtained by observing sales reps in action, and they can provide great insights into the skills and practices of a seller.

Metrics can also be reported on post-call activities such as coaching and completing documentation. Measures like Percentage of Calls with Debrief or Number of Calls Logged in CRM can ensure that these important tasks are occurring. Again, manual intervention is required to capture these numbers, but if Call Management is a critical activity for your sales force, then it is worth the investment of time to know that you’re maximizing the value of each and every sales call.

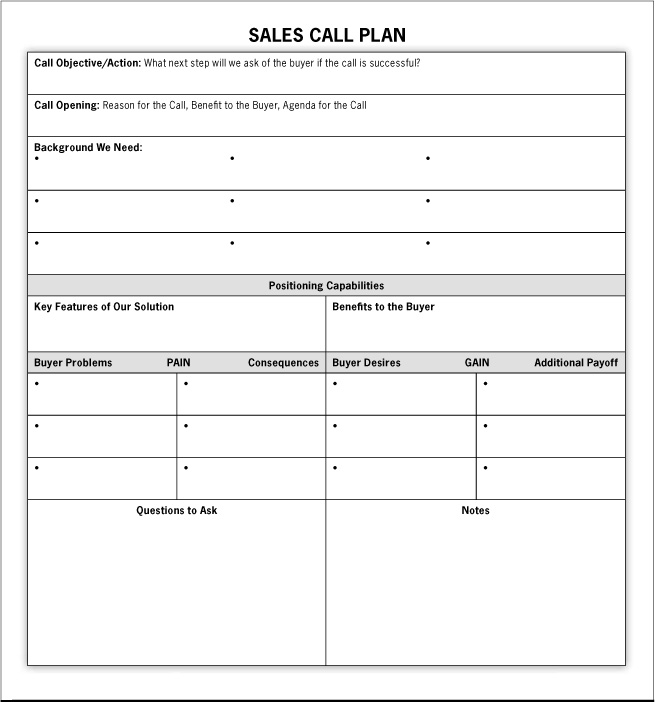

The Tools. The primary tool to support Call Management is, of course, the call plan. Call plans take salespeople through a structured and thorough approach to preparing for an upcoming sales call (see Figure 5.5). Call plans help reps conduct an effective customer interaction by forcing them to consider questions like these:

FIGURE 5.5 A Sample Call Planning Tool

![]() What are the call objectives?

What are the call objectives?

![]() What are the customer’s likely needs?

What are the customer’s likely needs?

![]() What information does the seller want to learn?

What information does the seller want to learn?

![]() What questions should the seller ask?

What questions should the seller ask?

![]() Which products or services should the seller and the customer discuss?

Which products or services should the seller and the customer discuss?

![]() What objections might arise?

What objections might arise?

Increasingly, call plans are integrated into a company’s CRM tool, though they can be just as effective on paper or in a desktop publishing application. We find that too often people obsess over the format or medium for their sales force’s call plans. The truth is, the point of call planning is not to create a plan. The only reason to create a call plan is to ensure that the planning took place. You simply want to make certain that the salesperson thoughtfully prepared for the call before it took place. Simply stated: the plan means nothing, but the planning means everything.

Common Issues. The most common question we get when working with clients to implement call planning processes, tools, and metrics is, When should a salesperson take the time to plan a sales call? Our first reaction is that a seller should never call on a customer without some level of forethought—even if it’s just to consider why the salesperson is there, why the buyer should care, and what the seller hopes to accomplish.

However, formal call planning is much more time-intensive than just considering a few basic questions. Depending on the volume of calls a salesperson makes, it’s often impractical for him to formally plan every call he makes on every prospect or customer. Doing so could consume days out of his week. Therefore, we tell our clients this:

![]() Formal call planning should be done only when it is needed.

Formal call planning should be done only when it is needed. ![]()

Our advice is to use a call planning process when a call is particularly important or somehow high-risk. Many routine sales calls don’t warrant the extra effort that formal planning requires, and forcing reps to complete a plan when it’s a low-value exercise transforms planning into administration. Sales managers need to set expectations with their salespeople as to when and how call planning should take place. Then, of course, they should measure the process to ensure that it’s happening.

A second issue that we often need to address with clients surrounds who is involved in the call planning process.

![]() Call planning should involve both the salesperson and his manager.

Call planning should involve both the salesperson and his manager. ![]()

Too often, call planning is considered the salesperson’s sole responsibility, and his manager’s only involvement is enforcing compliance with the process. “Did you do a call plan?” “Yep.” “Great.” While this is efficient for the manager, it misses two opportunities to leverage the Call Management process into higher performance and improved capability.

First, when managers work with their salespeople to develop call plans, the quality of the plan is almost always better. Beyond the fact that “two heads are better than one,” the manager’s own selling experience can help the seller identify holes in his preparation or flaws in his reasoning. Improved call outcomes result from a collaborative planning effort.

Second, the call planning process is a perfect opportunity for developmental coaching. It provides a structured and safe environment for a manager to assess his salespeople’s critical thinking skills and coach them to increased capability. Over time, collaborative planning not only leads to better calls, it leads to a better sales force.

In summary, Call Management is one of the most elemental ways that sales managers can exert control over the performance of their salespeople. By influencing the quality and the content of their sales force’s calls, managers can achieve specific Sales Objectives by guiding the behaviors of their reps in the field. In the absence of deliberate Call Management, sales reps will make critical decisions in the midst of battle. With a formal Call Management process, the battle plans will be drawn with a little more care.

Opportunity Management

![]() Most sales are not completed in a single customer interaction and require many sales calls before the sale is finally closed. Sales that involve multiple calls across different stages of a customer’s buying process might require an additional layer of sales process to navigate the opportunity successfully. In addition to managing the individual sales calls, it’s wise for salespeople to think deliberately about how they approach the end-to-end selling effort. This process is called Opportunity Management.

Most sales are not completed in a single customer interaction and require many sales calls before the sale is finally closed. Sales that involve multiple calls across different stages of a customer’s buying process might require an additional layer of sales process to navigate the opportunity successfully. In addition to managing the individual sales calls, it’s wise for salespeople to think deliberately about how they approach the end-to-end selling effort. This process is called Opportunity Management.

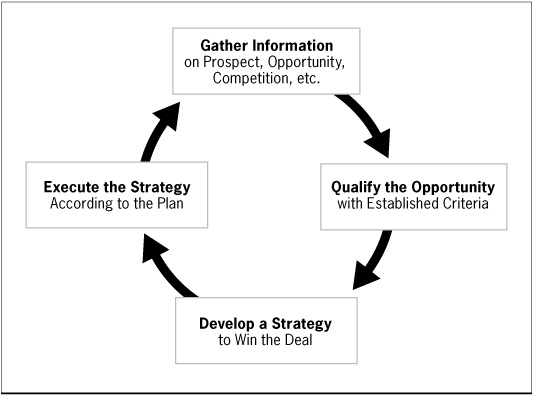

The Activities. Opportunity Management is a group of activities that helps a seller examine, qualify, strategize, and execute a single multistage sales pursuit. Like Call Management, there are both conceptual and tactical elements to Opportunity Management. But unlike managing individual calls, managing opportunities requires wider and longer-range vision, since there are more moving parts to consider in a complex sales cycle.

First the salesperson must gather information that is needed to fully assess the opportunity in the context of the customer, the seller’s organization, the competition, and other environmental factors. This information can come from online services, conversations with the customer, annual reports, records of previous customer interactions, industry publications, marketplace gossip, and just about any other source of information that one can imagine. Until full information is known about the opportunity and its surrounding circumstances, good planning cannot take place.

Once sufficient information has been gathered, the seller must qualify the opportunity to ensure that it’s worth pursuit. This should be done by judging the opportunity against clearly defined criteria that will steer your sales force toward deals that align with your company’s go-to-market strategy. If formal criteria are in place, your sales force will become expert collectors of highly desirable leads. If formal criteria are not in place, your salespeople will spin their wheels pursuing unwinnable or undesirable deals. Many sellers struggle to disqualify bad opportunities, and it shows in the bleak percentage of deals that actually win.

Next the salesperson must form a strategy to shepherd the opportunity successfully from beginning to end. This involves deciding how to align her company’s selling activities with the different stages and different participants in the customer’s buying process. Additionally, the seller has to determine how to best position her company’s products or services against those of the competition. With a coherent strategy in place, the salesperson can close a deal efficiently and effectively. Without a coherent plan, the seller can resemble a pinball being bounced around by every unanticipated discovery. No one wants to be a pinball.

Of course, your organization must then execute the strategy according to the plan. We say that your entire organization must execute because resources from anywhere inside a company can be engaged in an opportunity pursuit. In addition to the salesperson, there might be resources from engineering, marketing, finance, or other departments carrying out tasks in an opportunity plan. Even external resources such as other customers or industry luminaries are frequently involved in winning a complex opportunity. As with all winning strategies, accurate execution is crucial.

Unlike a Call Management process that has a discrete beginning and end, Opportunity Management is a circular process (see Figure 5.6). Once an organization begins to execute its plan, more information will come to light that could require a course correction in the strategy or even disqualify the opportunity altogether. Opportunity Management is iterative and should be expected to evolve as the sale progresses. Round and round the process goes, until someone makes a sale.

FIGURE 5.6 A Basic Opportunity Management Process

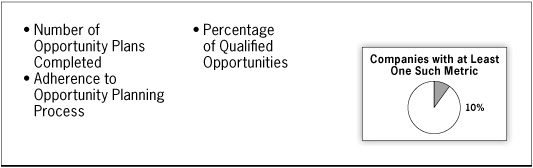

The Metrics. As with Call Management, the Opportunity Management metrics on our wall were mostly intended to measure compliance with the process. These were measures like Number of Opportunity Plans Completed or Adherence to Opportunity Planning Process. Also like Call Management, these metrics can be collected through sales force surveys, sales manager observations, or reports that are generated from the Opportunity Management tools themselves.

Disappointingly, very few companies in our study collected metrics on the activities associated with Opportunity Management (see Figure 5.7). However, the variety of metrics that could be reported is only limited by the nature of your sales process. One company in our research did track the percentage of opportunities that had been qualified by the sales force. We’ve known other sales forces that chose to measure things like the number of opportunities during which engineers, executives, or other company personnel accompanied their frontline sellers on sales calls because they felt it increased their chances of winning deals. We’ve also seen sales forces track the number of times certain products were proposed or certain types of buyers were contacted in an effort to shift focus among different products or customers. If it’s an important activity in pursuit of an opportunity, it can be tracked and reported in some fashion.

FIGURE 5.7 ![]() Sales Activity Metrics in Our Study: Opportunity Management

Sales Activity Metrics in Our Study: Opportunity Management

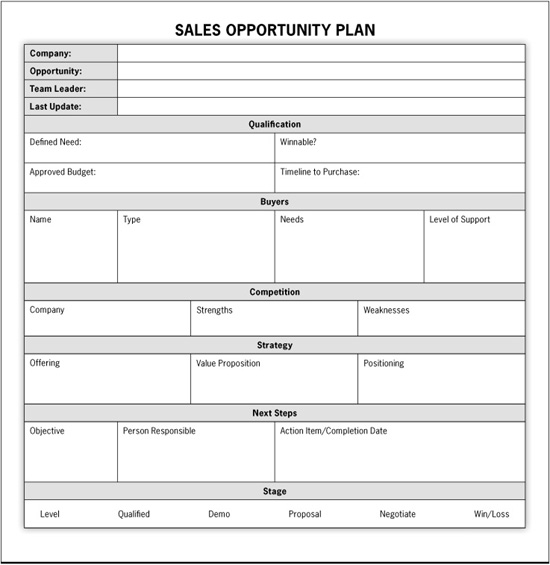

The Tools. The primary tool to support the Opportunity Management process is the opportunity plan. The format and contents of an opportunity plan should be customized to fit the way your sales force sells, but it is commonly designed to help salespeople thoughtfully answer opportunity-related questions like these:

![]() What is the nature of the opportunity?

What is the nature of the opportunity?

![]() Is the opportunity qualified?

Is the opportunity qualified?

![]() Who are the participants in the buying process?

Who are the participants in the buying process?

![]() What is important to them?

What is important to them?

![]() Who is the competition?

Who is the competition?

![]() What are our competitive strengths and weaknesses?

What are our competitive strengths and weaknesses?

![]() What will we offer the customers and why?

What will we offer the customers and why?

![]() What must we do to win?

What must we do to win?

![]() What are the steps in the sale?

What are the steps in the sale?

![]() Who should be involved in the sales process?

Who should be involved in the sales process?

![]() Where are their responsibilities?

Where are their responsibilities?

Like any planning tool, opportunity plans encourage structured thinking and make certain that all angles have been considered (see Figure 5.8). They can also serve as project plans for a deal pursuit team to organize its activities and track their completion. And of course, opportunity planning sessions provide an excellent venue for sales managers to coach their reps. When done collaboratively, the quality and impact of opportunity planning is greatly increased.

FIGURE 5.8 A Sample Opportunity Planning Tool

Other Opportunity Management tools are those that assist a seller in doing background research. During an opportunity pursuit, much information is needed as inputs to the process—information on the industry, company, buyers, competitors, marketplace, and so on. Useful tools for doing such research include external sources like online information services or networking tools, as well as internal sources like company intranets, CRM applications, or financial systems. Accurate and ample information enables good decision-making throughout the Opportunity Management process.

Common Issues. For a moment we’ll overlook the glaringly obvious issue that Opportunity Management, like Call Management, is being measured by so few companies. (Though it’s mind-boggling to consider that every sales force in the world makes sales calls and most pursue multistage deals, but these make-or-break activities are largely being left to chance in the field.) Instead, we’ll focus on the ironic fact that many leadership teams stand in their war rooms staring at shriveling pipelines, but their walls are missing the data that would help them drive pipeline growth. This is why:

![]() Opportunity and Call Management are the processes used to manage a sales pipeline.

Opportunity and Call Management are the processes used to manage a sales pipeline. ![]()

And as we mentioned before, we had loads of “Sales Pipeline” numbers on our wall before we recategorized them as Business Results or Sales Objectives. These metrics chronicled in great detail the size of a pipeline, the shape of a pipeline, and how capable a sales force is at moving deals through it. However, there were no pipeline numbers that got shuttled to the Sales Activity space.

That’s because there is no distinct pipeline management process. The sales pipeline is actually aggregated data on a sales force’s opportunities and calls. Milestones along a sales opportunity are the backbone of a pipeline, and successful sales calls are how opportunities advance through the sales cycle. Therefore, the closest you can get to managing your sales pipeline is to manage your salespeople’s opportunities and calls.

In short, Opportunity Management and Call Management are pipeline management, and the only way to proactively improve your pipeline is to formalize these two processes and track their associated metrics. Otherwise, your pipeline management processes will remain ad hoc in nature and, even worse, invisible to you. These numbers should be on war room walls, right beside the higher-level pipeline metrics that many executives can’t live without.

A second issue we observe regarding Opportunity Management is a tendency to develop opportunity plans that are far too complex. The goal of an opportunity plan is to ensure that structured thinking and planning is taking place on important deals.

![]() The goal is not to document all possible information about an opportunity.

The goal is not to document all possible information about an opportunity. ![]()

We often see companies treat opportunity plans as a comprehensive database of information on every aspect of an opportunity. The plan can be pages long and include data so tangential to the core opportunity that it looks more like a corporate biography than a plan to pursue a single deal. Leadership is prone to defend such monumental documents by saying, “If this salesperson died tomorrow, I’d want anyone in the sales force to be able to pick up this plan and finish the deal.” Interesting.

While it’s exceedingly unlikely that salespeople will start dropping dead en masse, we do understand management’s craving for visibility into important opportunities. The challenge is this: the more burdensome planning becomes, the less compliant sales reps will be to the process. Our advice is to keep Opportunity Management activities as streamlined as possible and focused on the task of enabling better selling. A greater level of process and rigor will almost always elevate salespeople’s performance, but too much rigor can kill them. Remember: the plan means nothing—the planning means everything.

Account Management

![]() If Peter Drucker was correct that the most basic purpose of a business is to create a customer, then there is a higher purpose that he forgot to mention: to create a repeat customer. Customers who purchase from you repeatedly over time not only provide an ongoing stream of revenue, but the cost of sale to existing customers is often substantially lower than that of faceless prospects. Any way you look at it, repeat customers fall squarely into the category of Things a Company Wants to Have.

If Peter Drucker was correct that the most basic purpose of a business is to create a customer, then there is a higher purpose that he forgot to mention: to create a repeat customer. Customers who purchase from you repeatedly over time not only provide an ongoing stream of revenue, but the cost of sale to existing customers is often substantially lower than that of faceless prospects. Any way you look at it, repeat customers fall squarely into the category of Things a Company Wants to Have.

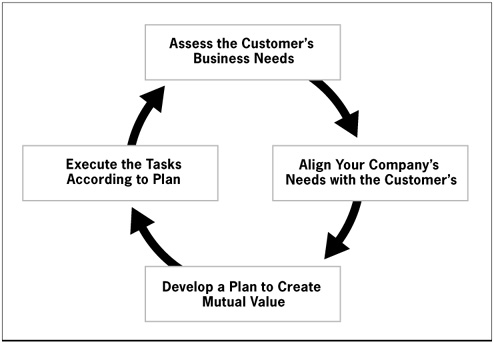

If your company receives a high proportion of its revenues from a concentrated number of loyal customers, then you need to be very deliberate about how you handle those critical relationships. There is a particular set of activities that can prove very useful in helping your organization retain and grow those existing relationships. Collectively, they’re known as an Account Management process (see Figure 5.9).

FIGURE 5.9 A Basic Account Management Process

The Activities. The ultimate goal of Account Management is to maximize the long-term value of a select group of customers. Whether these customers are the biggest, most profitable, or otherwise strategically important, they warrant additional attention from the seller’s company in order to increase loyalty and profits. Account Management activities essentially tailor a company’s go-to-market strategy to each chosen customer through careful analysis, planning, and execution at the individual account level.

The first activity in a good Account Management process is to assess your customer’s business needs. By understanding your customer’s long-range strategy and short-term objectives, you can not only align your products and services with its top-of-mind issues, you can also look for innovative ways to help your customer further its own business objectives. Research shows that customers highly value suppliers that have an innovative eye and proactively bring new ideas to their customers.3 This can only happen if you invest the time to assess your customer’s business deeply.

Once the customer’s needs are known, you must develop an account strategy that will align your company’s needs with the needs of your customer. Clearly your company will have its own agenda for the account—increasing Share of Wallet, introducing a new product line, expanding into other parts of its organization, or some other Sales Objective that will yield better Business Results. However, your agenda can only be accomplished if it in some way supports the customer’s agenda. A winning account strategy will consider both sides of the relationship and find strategic alignment between your organizations’ goals.

Of course, that winning strategy can only be brought to life if you develop a plan outlining the required tasks. The planning effort should be led by the salesperson, but it could include people from across the seller’s organization. In addition to the salesperson’s manager, account planning often engages other sellers who assist with cross-selling, operational staff who improve customer service levels, external partners who provide related services, executives who engage the customer at higher levels, or any other people who must play a role in achieving your goals for the account.

Finally, there’s the pesky chore of flawlessly executing the plan. Account Management is very much a team sport, and in this case, the salesperson is the coach. Not only must your seller diagram the plays in the account plan, she must ensure that her teammates are performing as expected. It can be challenging for a salesperson to coordinate resources that are not accountable to her, but the seller must find a way to rally the necessary troops. It’s the salesperson who is ultimately accountable to her customer … and to her manager … and to her quota. So she is the one who has to make it happen.

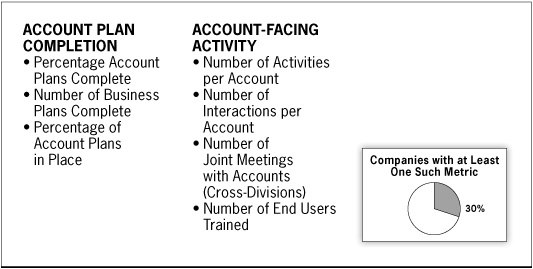

The Metrics. The Account Management metrics we saw on our wall fell into one of two categories. Like Call Management and Opportunity Management, there were numbers that were intended to drive compliance with the planning process. In the case of Account Management, all of these metrics assured that planning was taking place by assuring that the plans were in place. Measures like Percentage of Account Plans in Place or Number of Business Plans Completed were reported, as you might expect.

The second group of numbers was focused on tracking interactions between the company and its customers (see Figure 5.10). Metrics like Number of Activities per Account and Number of Joint Meetings with Accounts reveal not only the intensity of customer relationships but also the nature of their interactions. Depending on your go-to-market strategy or the contents of your account plans, you could track a metric for nearly any customer-facing activity.

FIGURE 5.10 ![]() Sales Activity Metrics in Our Study: Account Management

Sales Activity Metrics in Our Study: Account Management

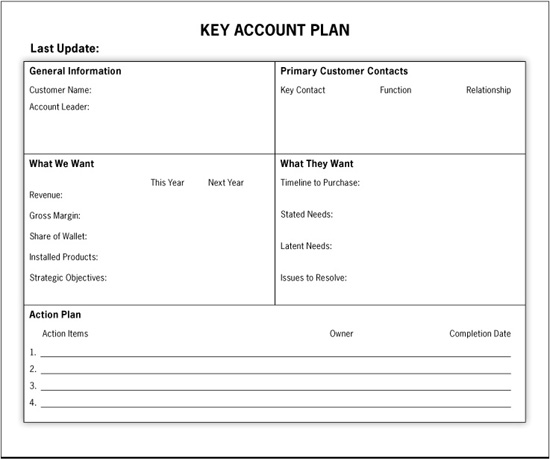

The Tools. As you can see from the first group of metrics, an account plan is the key tool for Account Management activities. Account plans can range in size from a page to a small book, depending on the level of detail that an account plan captures. Regardless of the plan’s size, the tools are used to take a salesperson or the account team through a structured process of setting account objectives and planning how to achieve them. Questions that are commonly asked include these:

![]() What are the customer’s strategic initiatives?

What are the customer’s strategic initiatives?

![]() How can we help the customer accomplish them?

How can we help the customer accomplish them?

![]() What do we want to get from this account?

What do we want to get from this account?

![]() What will we have to give them to get it?

What will we have to give them to get it?

![]() Who are the key stakeholders at the account?

Who are the key stakeholders at the account?

![]() Do they consider us friend or foe?

Do they consider us friend or foe?

![]() What do we need to do in the next month, quarter, year, or longer?

What do we need to do in the next month, quarter, year, or longer?

![]() Who from our organization must be involved?

Who from our organization must be involved?

![]() What must they specifically do and when?

What must they specifically do and when?

The list of potential questions could literally go on forever. Account plans can include information such as customer financial data, past purchasing history, incumbent competitors, issues between the two organizations, industry dynamics, and anything else that the seller’s company thinks is important or somehow interesting (see Figure 5.11). Practically, the length to which account plans can go is sometimes limited by the number of accounts the organization deems plan-worthy. If each salesperson is planning for 20 customers, then clearly the account plans must be rudimentary. However, if 20 people inside the selling organization are dedicated to a single large account, then it might require a book-sized document to hold information required for each of the many stakeholders.

FIGURE 5.11 A Sample Account Planning Tool

Of course, discretion is advised. We’ve time and again examined clients’ account plans only to find pages of extraneous data. We always ask them, “What are those random pieces of information doing in there?” And the answer is always the same: “Because one person thought we needed it.” As with any type of planning tool, there is merit in keeping things simple.

Common Issues. Companies that are heavily engaged in Account Management will tell you how important the process is to retaining and growing key accounts. And if the majority of your profits come from a small number of customers, it is nothing short of a necessity. But even in organizations that view Account Management as a mission-critical process, we still find two widespread behaviors that diminish the value of their sales forces’ efforts.

The first misbehavior is treating Account Management like an annual event. Many, many companies invest lots of time in account planning toward the end of the calendar year, only to let their account plans sit on the shelf like an annual report. The work that went into them was solid, and the action plans would have a great impact on the targeted accounts, if the plans were ever executed.

Like Opportunity Management, Account Management is an iterative process. Though the heavy planning takes place at a defined interval (most commonly once a year), the activities are ongoing, and the account plan is a living document. If the plans are not used as operational guidelines for the account and updated frequently, they are little more than annual intermissions of strategic thinking separated by long expanses of random actions. If Account Management is important to your organization, then do it. If not, then do not. But don’t find yourself in the middle ground of investing moderate effort with zero return.

The second Account Management misbehavior is failing to involve customers in the process. To some, this may seem like an outlandish proposition. Why ever would you involve a customer in your account planning activities? Because that’s the only way to gain strategic alignment between the two organizations and maximize the mutual benefit of the relationship. Let us give you an example of when neglecting this fact wasted a lot of one company’s resources.

We were recently examining the Account Management processes of a major corporation, and its executives were explaining to us the tensions between its sales force and one of its largest customers. The customer had been with the company for more than a decade and was generating more than $100 million in revenue each year. The company had an entire team of salespeople and customer service reps dedicated to this single customer—however, things were not good.

Company Sales Executive: For a number of reasons, our relationship with this account has really soured over the last couple of years.

Vantage Point Performance: What have you done to try to mend the wounds?

Executive: Well, you know that this major account doesn’t actually consume the product that we sell them—they bundle it with their own products and resell it to their customers as a packaged solution. The end customer knows us by name but doesn’t purchase directly from us.

VPP: Yes. We understand. Your product is used by your major account’s customers.

Executive: Right. So this year we launched a huge initiative to get to know our customer’s customers—the ones who actually use our product. The reasoning was that if we could improve the end users’ experience with our product, then it would also improve their experience with our major account’s products. Our major account had complained about the end users’ experience in the past, so it made a lot of sense.

VPP: And how is it going?

Executive: It’s a disaster.

VPP: Why?

Executive: The major account said it didn’t want us to do it.

VPP: What do you mean, it didn’t want you do to it?

Executive: Their leadership team said that there were other operational issues they wanted us to focus on instead.

VPP: But, weren’t they the ones who asked you to get to know their customers?

Executive: No. They didn’t ask us. We just thought it was the right thing to do.

VPP: So, you launched that entire initiative without any input from your major account?

Executive: Yes, and it didn’t help our relationship at all. They are really very upset about the operational issues.

VPP: Didn’t that come out in your account planning discussions with them at the end of last year?

Executive: No. We don’t typically involve customers in our planning processes.

VPP: Why not? Wouldn’t involving them in the process have prevented you from wasting a lot of time and money this year?

Executive: Yeah. Probably. That’s perhaps something we should consider doing in the future.

VPP: I’d say that’s definitely something to consider.

Failing to include its major customer in their Account Management activities not only caused our client to waste lots of resources on an unwanted initiative, it distracted executives from making operational improvements that would have helped to heal their fractured relationship. You can only align your sales force’s efforts with your customers’ objectives if you collaborate during account planning activities. If nothing else, it might be something to consider.

Territory Management

![]() With rare exception, salespeople are responsible for selling to more than a single customer. In fact, sales reps will frequently have a database with hundreds of prospects and customers that they contact on a routine basis. Whether organized by geography, industry, size, or some other corporate characteristic, most salespeople are assigned a defined group of target customers. This group of targets is commonly referred to as a sales territory.

With rare exception, salespeople are responsible for selling to more than a single customer. In fact, sales reps will frequently have a database with hundreds of prospects and customers that they contact on a routine basis. Whether organized by geography, industry, size, or some other corporate characteristic, most salespeople are assigned a defined group of target customers. This group of targets is commonly referred to as a sales territory.

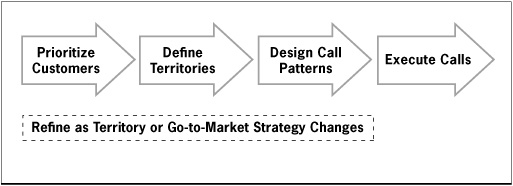

Anyone who has ever owned a sales territory can attest that there is never enough time to fully serve all of these prospects and customers. And even if there were, certain customers deserve more attention than others. Therefore, one of the most important decisions a seller has to make on a daily basis is this: How do I allocate my time across all of the customers in my territory? This process of identifying, prioritizing, and calling on target customers is called Territory Management.

The Activities. While the first three sales processes we explored are designed to increase the effectiveness of a sales-person’s effort, Territory Management is all about efficiency. Stated in more tactical terms, Call, Opportunity, and Account Management processes help your salespeople improve what they do when they are face-to-face with a customer. Territory Management helps sellers get face-to-face with as many qualified customers as possible given their time and resource constraints. If you only have so many hours each day to call on customers, you’d better use them wisely.

The first activity in managing a territory is to prioritize your customers. Without a clear customer hierarchy, all customers look alike to a sales force. Customer prioritization should be determined by your company’s current Customer Focus objectives. Whether the Sales Objective is to win customers in a particular industry, acquire customers that buy certain products, or grow revenue from existing customers, your Customer Focus should determine how you identify high-priority customers. And if your Customer Focus objectives happen to change over time, then so should your Territory Management priorities. You need to know your target before you can hit it.

The second Territory Management activity is to define the territory. Despite the fact the word territory in everyday language refers to a geographic patch of land, in the world of sales, a territory can be virtual. That is, a salesperson could be assigned a territory that is a handful of accounts spread all across the globe. Customers in a territory do not have to be in close proximity to one another; they simply have to be assigned to a rep.

Some companies choose to redefine their sales territories on a periodic basis—say annually. Others do so only as circumstances change—when they hire new salespeople, shift their Customer Focus, or perceive changes in the marketplace. Regardless of how frequently you reconfigure your territories, making sure that the territories are configured properly for each sales rep is a vital step toward good territory management.

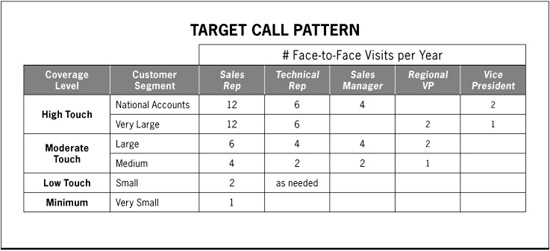

The third activity is to design customer call patterns. These are the tactical plans that communicate the frequency with which certain types of customers are to be called. For instance, if your Customer Focus objective for the year is to acquire new customers, then you might choose to direct more of your sales calls toward prospects than toward existing customers. If your objective happens to change to increasing Share of Wallet with current customers, then your priorities would shift, and you would reallocate those sales calls back toward existing accounts. With this example, you can begin to see how managing Sales Activities so powerfully affects the attainment of specific Sales Objectives.

Finally, your sales force must execute its designated call patterns according to plan. When call patterns are closely followed, the sales force becomes that nimble strategic weapon that can be confidently redirected as circumstances change. But when call patterns break down, the sales force becomes an unguided brute, hitting its target only by luck or providence. An undisciplined sales force not only makes inefficient use of your sales force’s effort, it can also threaten the achievement of your company’s stated Sales Objectives.

It is worth reiterating that Territory Management is subject to constant refinement. As market dynamics or Sales Objectives change, you should reengineer your territories and redesign your call patterns (see Figure 5.12). Particularly if your company has constantly evolving product and customer priorities, we cannot overstate the importance of keeping Territory Management activities aligned with your Sales Objectives. Otherwise, your sales force may be dutifully executing last year’s strategy.

FIGURE 5.12 A Basic Territory Management Process

Also, we should mention that the first three Territory Management activities are often performed by the organization for the salesperson. Defining territories, prioritizing customers, and even designing call patterns involve a level of analytics and organizational alignment that are perhaps best done by sales management or a sales operations support group. However, the accurate execution of the call pattern is unquestionably the responsibility of the salespeople, and they must be held accountable in order for your market-facing objectives to be met.

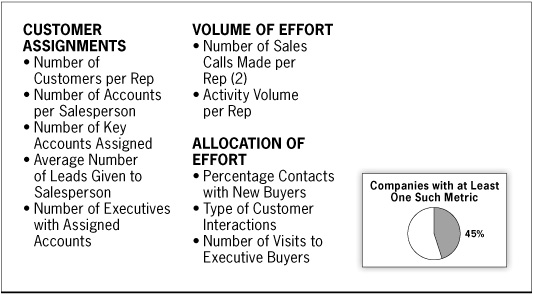

The Metrics. In our research, we noted three distinct types of Territory Management metrics (see Figure 5.13). The first measures activities toward the front of the process—assigning customers and prospects to the sales force. Metrics such as Number of Customers per Rep and Number of Key Accounts Assigned are intended to ensure that customers and prospects are assigned to sales reps in the correct quantity and ratio. Too many customers, too few customers, or unassigned customers can lead to an inefficient selling effort.

FIGURE 5.13 ![]() Sales Activity Metrics in Our Study: Territory Management

Sales Activity Metrics in Our Study: Territory Management

The second type of metric focuses on the volume of effort that salespeople are applying to their territories. Measures such as Number of Calls Made or Activity Volume per Rep represent the most “old-school” of old-school metrics. They reveal how hard your salespeople are running but not in which direction.

The third and final flavor of Territory Management metrics are the type that we find most useful because they reflect the sales force’s allocation of effort across a company’s desired targets. Numbers such as Percentage Contact with New Buyers and Type of Customer Interactions shed light on how salespeople are investing their time across different types of buyers and different types of sales calls. If acquiring new customers is one of your Sales Objectives, then you do not only want to know how many calls your sellers are making—you want to know how many calls they are making on prospects. Metrics like this transform the old school into higher education.

The Tools. Unlike Call, Opportunity, and Account Management activities that are performed continuously in the field, most Territory Management activities are completed on a periodic basis and often by a centralized group. Consequently, a company can afford to spend a lot of time trying to get its Territory Management strategies and tactics correct. And since these decisions lend themselves to in-depth quantitative analysis, very sophisticated analytic tools have been developed to support this process.

Territory definition is probably the most quantitative exercise in the Territory Management process. Ideally, each salesperson’s territory would be perfectly sized to utilize 100% of his available time to call on customers, and his mix of customers and prospects would perfectly mirror your company’s Customer Focus objectives. While some companies simply assign convenient chunks of geography to their salespeople with little regard for the territory’s composition, other companies scrutinize travel time and salesperson availability down to the minute in an attempt to create perfect territories. We’ve worked with companies at both extremes and tend to prefer a more analytic approach, within the boundaries of reason.

The most common tool to use to prioritize customers and design call patterns is the electronic spreadsheet (see Figure 5.14). Since the goal of these activities is to determine which customers are most desirable and how many sales calls can be allocated to each, spreadsheets are useful for the many iterative calculations required to reach agreement on the actual targets and the distribution of salesperson effort. As always, which tool you use is not as important as the deliberate thought that goes into making these critical decisions.

Executing the call patterns is of course a very manual activity. You could say that the tools here are the salesperson’s means of transportation and communication: planes, trains, and automobiles. Phones, computers, and mail. The tools of choice are any means that will get the seller most efficiently in front of her target customers and prospects.

FIGURE 5.14 A Sample Call-Pattern Design Tool

Common Issues. When companies choose to engage in Territory Management, the issues are rarely with the analytics. Sales leadership is more than capable of designing adequate territories and call patterns. The problems arise in the execution of the call patterns, and there are two issues that are particularly meddlesome.

The most disruptive factor in call pattern execution is “fire-fighting.” Despite the best-laid plans for proactive, high-value sales calls, salespeople with assigned accounts are susceptible to becoming full-time troubleshooters for their customers. Even in organizations with dedicated customer support roles, the salesperson is still the primary firefighter in the mind of the customer. And there is always a fire smoldering somewhere.

This problem can only be resolved through self-restraint by both salespeople and their managers. To be practical, some level of customer service is inherent in many selling roles. However, it should be meted out in the bare-minimum quantity and only to high-priority issues. If every customer can send its sales rep in search of a corrected invoice, then sales force call patterns don’t need to be directed toward external customers—they need to be directed at finance, operations, and every other internal corporate function.4

The second issue that destroys the integrity of good Territory Management has been mentioned previously, the hit-your-number-any-way-you-can mentality demonstrated by a lot of management teams. In pursuit of the ultimate Business Results, objectives like Market Coverage and Customer Focus get disregarded by those who perceive a different path to success.

When the generals in the war room order their troops to capture a hill, it’s unacceptable for the troops to capture a valley instead. Even if the leaders on the ground can claim that it’s a bigger plot of land and they incurred fewer casualties, the troops deviated from a strategic plan that was carefully designed to win the overall war. They put the greater outcome at risk in order to achieve an easier near-term objective. That’s why there is a war room in the first place—to make sure that the many individual battles are coordinated and building toward an eventual victory.

If you believe that the wise allocation of sales calls will substantially affect your sales force’s productivity, then you should put the appropriate processes, tools, and metrics in place for effective Territory Management and then make it happen. Communicate your expectations, and inspect that they are being met. As with any sales process, discipline is required to reap big rewards.

Sales Force Enablement

![]() We’ve made the case that management rigor is a key driver of sales force performance. With focused attention on how calls, opportunities, accounts, and territories are managed, sales leadership can steer its teams most directly toward its company’s desired Sales Objectives and Business Results. In other words, sales success is built on sound execution of the right Sales Activities.

We’ve made the case that management rigor is a key driver of sales force performance. With focused attention on how calls, opportunities, accounts, and territories are managed, sales leadership can steer its teams most directly toward its company’s desired Sales Objectives and Business Results. In other words, sales success is built on sound execution of the right Sales Activities.

However, all of these activities are executed by individuals, and the capability of those individuals plays a tremendous role in the soundness of their execution. Although we still encounter unenlightened companies that treat their salespeople as disposable commodities, the vast majority of sales leaders today recognize that highly capable sellers are worth their weight in Business Results. Consequently, they invest heavily in their sales forces to build their capabilities and improve execution in the field. This process of investing in improved sales execution is called Sales Force Enablement.

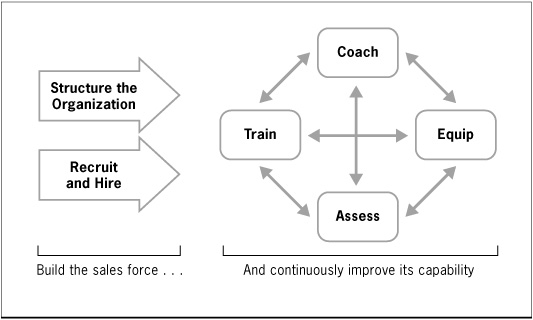

The Activities. As we mentioned in Chapter 4, Sales Force Capability is more than just the skill of the sales force—it also encompasses the greater system in which salespeople operate. This includes the strategies the salespeople employ, the processes they follow, the tools that support their activities, the expectations that are communicated to them, and many other elements that go well beyond the scope of only training to develop skills. Capability basically incorporates every aspect of how a salesperson does her job. Accordingly, Sales Force Enablement includes a variety of tactics that an organization can use to increase its sales force’s ability to execute (see Figure 5.15).

FIGURE 5.15 A Basic Sales-Force Enablement Process

First, management should structure the organization in a way that provides its salespeople with access to the resources they need to perform their jobs efficiently and effectively. If the sales manager plays a pivotal role in your seller’s day-to-day activities, then where you locate your managers and how many reps you assign to each will have a great impact on salesperson performance. Or if your typical sale involves roles such as technical engineers or other specialists, then easy access to those individuals is a must-have for your salespeople. The coordination of internal resources is often required in complex sales, and organization structure can influence it tremendously.

Second, you must recruit and hire salespeople to staff your organization appropriately. If your sales force is chock-full of talented sellers, then the burden on every other Sales Enablement activity is reduced. But if your sales force is ladened with mediocrity, you will have to invest heavily to elevate sales performance. We should note that recruiting and hiring not only has a direct impact on the objective of Sales Force Capability but also on Market Coverage. Having the right number of skilled salespeople onboard makes a manager’s world a much happier place.

Clearly, you need to train your sales force to develop the skills and knowledge necessary to capably execute its Sales Activities. Training is the most widely used means of Sales Force Enablement, and it is a very efficient way to fill capability gaps that are common across a sales force. Training is so deeply embedded in the sales culture that it really requires little explanation.

Another way to develop your salespeople’s skills and knowledge is to coach them individually. Whereas training is designed to instill common knowledge across a sales force, coaching is used to build a salesperson’s abilities based on her unique development needs. As Sales Force Enablement activities go, this is the most value-added of them all. Unfortunately, it’s also the most time-intensive for a manager, so it must be done in a deliberate and thoughtful way.

You also must equip your salespeople with tools or job aids that support their selling activities. From sales presentations, to proposal templates, to communication devices, and a vast assortment of other documents and gadgets, salespeople have more tools in their hands today than ever before. Organizations have discovered that equipping their sales forces with relevant tools is a high-leverage investment that promotes consistent execution across an organization.

The final Sales Force Enablement activity found in our research is to assess the sales force. Sales force assessment can be done in many different ways using many different tools and methodologies. We prefer to use a combination of assessments to get several perspectives on potential issues—both at the individual and organizational levels. However you go about it, assessing the capability of your sales force has broad implications for how you approach the other enablement activities.

As you might have concluded, the Sales Force Enablement “process” is really a collection of ongoing activities. Some activities such as coaching should be done on a never-ending basis, though few companies coach enough. Others, such as restructuring the sales organization, can be done episodically, though we know companies that scramble their org charts almost daily. These activities are also highly interrelated; for instance, you could train someone on how to use a new sales tool and then reinforce that skill with coaching. The greater point is that there is a selection of Sales Activities in which sales management can make deliberate investments to achieve specific Sales Objectives.

To give an example, if you set an objective for the year to increase your Percentage of Proposals Won, there are several Sales Enablement activities that you could use as levers:

![]() Recruit and hire dedicated proposal writers to review and edit all proposals.

Recruit and hire dedicated proposal writers to review and edit all proposals.

![]() Structure your team so that each region has its own proposal writer.

Structure your team so that each region has its own proposal writer.

![]() Equip your sales force with proposal templates for different types of products or customers.

Equip your sales force with proposal templates for different types of products or customers.

![]() Train your salespeople on how to use the templates.

Train your salespeople on how to use the templates.

![]() Coach them through the development of several proposals.

Coach them through the development of several proposals.

![]() Assess their proposal writing skills at regular intervals.

Assess their proposal writing skills at regular intervals.

![]() Refine all of the above based on your results.

Refine all of the above based on your results.

If you took an approach like this, it would seem impossible for you not to make progress toward your objective. And there are probably dozens of other activities that you could also undertake requiring varying levels of investment. But you can see how a robust Sales Force Enablement effort that is focused on a specific Sales Objective will have a predictable and profound impact on your sales force’s performance.

It’s worth mentioning that Sales Force Enablement activities are not the sole domain of the sales force. While they are typically overseen by sales management, they can also be owned or supported by human resources, information technology, or other corporate functions with the appropriate competencies. In fact, many of these activities can be outsourced, as we do a fair amount of assessing, training, and coaching sales forces for our clients. Regardless of who carries out the activities, sales management should be responsible for setting the Sales Force Enablement agenda and then measuring its outcomes.

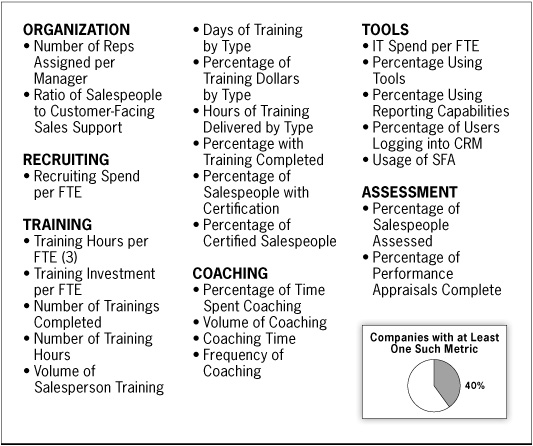

The Metrics. Of all the Sales Activities numbers on our wall, Sales Force Enablement metrics were the most prevalent by far—representing more than 50% of the activity-level measures. Since the metrics themselves revealed the activities we just described, we of course observed metrics that aligned with each activity (see Figure 5.16).

FIGURE 5.16 ![]() Sales Activity Metrics in Our Study: Sales Force Enablement

Sales Activity Metrics in Our Study: Sales Force Enablement

With regard to organization structure, we found metrics such as Manager Span of Control and Ratio of Salespeople to Sales Support. These measures show whether staffing levels are in balance among various resources for the salesperson. By providing sellers with adequate oversight and support, leadership helps its reps function at full capacity.

We witnessed only one hiring metric study, which was Recruiting Spend per FTE. However, we have known companies that track things like Number of Recruiting Events Held, Number of Candidates Interviewed, and other measures of recruiting activity to make sure their pipeline of potential employees remains full.

Roughly half of the Sales Force Enablement numbers on the wall were intended to measure some aspect of sales training. Metrics like Training Hours per FTE show the volume of training taking place, while numbers like Days of Training by Type put a finer lens on the precise types of skills that are being emphasized. A final type of training metric like Percentage of Certified Salespeople demonstrates that the sellers had completed a formal training program. It is clear from our research that leadership is very focused on monitoring its training investment.

We were pleased to find several coaching metrics in the mix, such as Percentage of Time Spent Coaching and Frequency of Coaching. As we mentioned previously, companies are increasingly expecting their sales managers to engage in active coaching. Measures such as these not only indicate that coaching is taking place, but they also force an organization to deliberately define what, why, when, where, and how it wants coaching to take place.

We were also encouraged to discover metrics on sales tools. Numbers such as IT Spend per FTE measure the level of investment a company is making in its supporting infrastructure, and metrics such as Percentage of Users Logging into SFA reveal whether or not the investment is being leveraged by the sales force. As we provide greater insight into the effective use of metrics, we hope that numbers like these gain in prominence.

The final type of Sales Force Enablement metric we encountered was pointed toward assessing the sales force. Measures like Percentage of Salespeople Assessed and Percentage of Performance Appraisals Complete can give management confidence that the sales force is at least aware of its own capability. Performance assessments are also essential to any ongoing continuous improvement efforts.

The Issues. The Sales Enablement activities that a company could potentially undertake are so diverse that we could write a separate book on the issues associated with this process. But let us highlight one that is particularly widespread and leads many companies to waste massive amounts of time and money. It is the ready-fire-aim approach that companies frequently take when deploying new Sales Enablement initiatives.

Any meaningful Sales Force Enablement program requires a large investment of company resources, and implementing real change can be very disruptive to a sales force. You would expect, then, that companies would be extremely careful to identify, analyze, and prioritize their sales improvement alternatives before making such consequential commitments on behalf of their sales forces. However, we know few companies that do a thorough job of assessing their sales forces’ needs before charging into expensive change efforts that yield questionable returns on their investment. Such decisions are routinely made based on anecdote, inertia, or convenience, with predictably lackluster outcomes.

For instance, a company once asked us to help it redesign its sales processes as part of a larger sales-force automation project. Leadership was adamant that it needed an expensive new CRM tool, despite the fact that its sales force loved the company’s existing system, and it had no major functional deficiencies. When we quizzed the leadership team on why it wanted the new CRM application, the leaders responded, “Well, this one is getting pretty old, and it’s no longer best-practice.” Whether or not that was true, we saw several other problems with its sales force that could have been fixed for a much smaller investment and with a much greater return. But the team had not assessed its Sales Force Enablement alternatives—it simply decided to replace the CRM tool. We don’t know how these leaders got the itch, but they scratched it without looking at other more serious wounds.

A second example is one that we encounter repeatedly: the launching of a major sales training program without any analysis of the sales force’s true enablement needs. We’ve talked more than one company out of conducting training that they approached us to facilitate because it was obvious to us that it wouldn’t produce the results they were expecting. In some cases, we felt they had selected the wrong type of training, but in others, we determined that their issue wasn’t even a deficiency of skill. They really needed better processes, tools, or other systemic contributors to sales performance. Training is often the easiest place to go for a Sales Enablement initiative, but it is not always the right destination. Though training your sales force on irrelevant skills probably won’t harm your salespeople, it sure will waste their time. And your money.