CHAPTER 6

Building the Foundation for Control

THE BUILDING BLOCKS

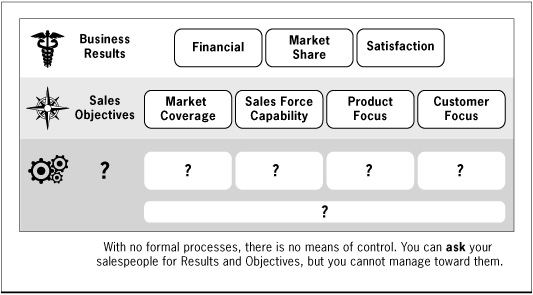

We’ve made the point that sales processes are the building blocks of control over sales force performance. Since you can only truly manage your salespeople’s activities, you must achieve your Sales Objectives and Business Results by implementing formal processes that you can tactically direct and measure. With process rigor, you can manage the territories, accounts, opportunities, and calls that lead to successful sales outcomes. Without process rigor, you are asking for the outcomes but leaving the critical tactics to chance.

This latter state of affairs is what faced senior executives at the $400 million software company we discussed in the previous chapter. The company’s VP of sales had put rich incentives in place for his salespeople and then let them run free to sell as they wished. This “management by results” approach worked just fine when the market was growing wildly, but it crippled management’s ability to control its sales force when the joy ride came to an end. When the managers ultimately needed the levers and pulleys to control sales performance, they found that their hands were empty.

The software company’s leadership soon came to the conclusion that “management by results” was not the best strategy. “Management of activities” is a much more satisfying way for executives to live their lives. Therefore, they went down the path of implementing formal sales processes to gain control of their sales performance. Starting with a blank page, they designed new sales processes that defined the way they wanted their salespeople to sell. Despite the fact that the company had already grown into a sizeable corporate entity, leadership returned to the most basic of decisions—what do we want our salespeople to do?

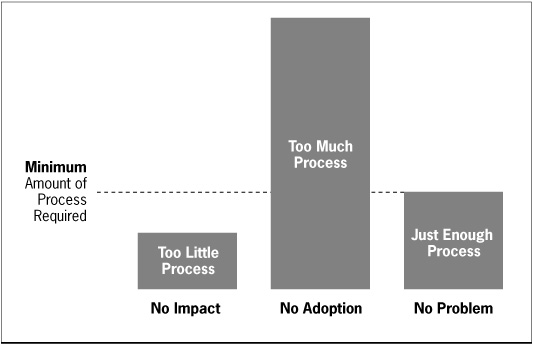

This is the kind of back-to-basics exercise that must be conducted before you can progress to the more advanced task of architecting a system of metrics that will allow you to attain your desired Business Results. To fully avail yourself of the newly cracked sales management code, you must first put in place the formal processes that will enable you to proficiently measure and manage your Sales Activities. Even if you already have a formal process in place, we encourage you to review your current state of affairs to make certain you’re working from a solid foundation. Until the levers and pulleys are in place for you to control the selling effort, you will necessarily remain in a management-by-results quandary (see Figure 6.1).

FIGURE 6.1 Sales Processes: The Building Blocks of Control

With increasing frequency, executives are coming to us for these exact reasons—either to implement formal sales processes for the first time or to reexamine their existing processes and make them more potent. This tells us that sales has finally turned the corner toward a structured management discipline and leaders are now reaching for the levers and pulleys to take control of their sales forces. And as we work with them to explore their companies’ process needs, they invariably ask a question that has been posed to us many times: “Which sales process is best for our company?”

WHICH SALES PROCESS IS BEST FOR OUR COMPANY?

It seems to be a reasonable question. If we know all of the facts about our company, how hard can it be to choose a process that will best fit our sales force? Unfortunately, it’s not only hard to answer this common question, it is impossible. And the reason the question is impossible to answer is because it’s the wrong question to ask. Let us share another client experience that will illustrate why this is the case.

One of our own repeat customers once asked us to help redesign the company’s training curriculum for frontline sales managers. Leadership had decided that the company’s existing training modules were too generic (which they were), and it wanted to build something more focused on the way its sales force actually sells. More specifically, it wanted to move away from teaching generalized coaching skills and focus all of its manager training on the actual activities of its salespeople. The company’s executives felt this would prepare their managers to provide more relevant coaching in the field and to reinforce specific behaviors that were known to be important. From our perspective, they had formed a brilliant plan. So far, so good.

But they went on to say that they thought the challenge of coaching salespeople would be easier if all of their sellers used a common sales methodology. This would promote uniformity across their company—both in their overall sales approach and the management of their salespeople. Therefore, they wanted us to help them develop a single sales process that they could deploy across their entire organization. A single sales process, for their entire organization. Unknowingly, they had just ruined their previously stellar plan. So far, not so good.

They’d effectively asked us the question, Which sales process is best for our company? To understand why this was a bad question to ask, consider that this is a multibillion-dollar global conglomerate with dozens of sales forces selling dozens of different products to thousands of different customers. Even within a single sales force, they might have several different types of salespeople, each doing different things. For example, one of their sales forces includes geographic sales reps who manage territories, lead generators who manage cold calls, as well as strategic account managers who manage major customers. How could they ever design a single sales process that would be relevant for every salesperson in this sales force—let alone the entire company? They couldn’t. It would be impossible. No single sales process could help them manage all of their various selling roles, because each role has its own unique activities that are driving toward unique goals. This is why it’s almost always futile to ask which sales process is best for a company.

Unless the company has only one sales role and all of its sellers do exactly the same things, no common sales process will do the job. The right question to ask when you are selecting a sales process is, Which process is right for this specific role in my sales force? Not what is right for your entire company—just for a single role. This is an extremely critical point to understand as you begin to implement or redesign your formal sales processes:

![]() The specific sales processes you need in your sales force are determined by the nature of each individual selling role.

The specific sales processes you need in your sales force are determined by the nature of each individual selling role. ![]()

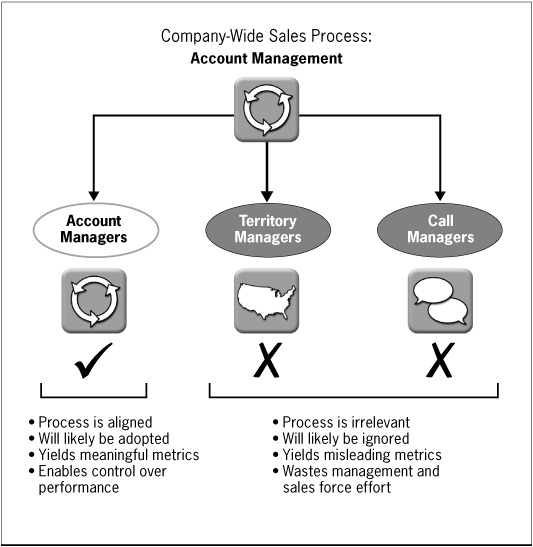

This might appear to be a game of semantics, differentiating between a company’s sales force and its individual selling roles, but it is anything but that. What good would a company-wide Account Management process do for a salesperson making 50 outbound lead-generation phone calls each day? None. And what good would a company-wide Territory Management process do for a strategic account manager who has only one assigned account? None. Yet how many times do you think companies deploy Account Management processes across every role in their sales force? Many. And how often does sales management try to track the time allocation of its major account managers? Often. These are all well-intentioned management errors but errors nonetheless.

This can be another brick-meet-forehead moment for sales leaders—that different selling roles require different sales processes. Which formal processes you deploy should be determined by the nature of each distinct role in your sales force. If you choose the right processes, what you are attempting to measure and manage will align naturally with the activities of your sellers. If you choose the wrong sales processes, the numbers on your war room walls will produce nothing but noise. And that noise will be screams from the battlefield where your sales force is being asked to do unnatural things.

From the perspective of salespeople in the field, being measured and managed in ways that don’t align with their known world is exceedingly frustrating. It not only causes them to resent being made to follow misaligned processes, it raises suspicions that leadership isn’t in tune with the reality on the ground. We once interviewed a sales manager who demonstrated symptoms of such a frustrating situation.

Vantage Point Performance: So, tell me a little bit about what your salespeople do. What are their primary activities?

Frustrated Sales Manager: Well, they’re basically account managers. Each of them is assigned to one of our major customers, and they’re responsible for structuring the business relationship between our two companies and then ensuring that things operate smoothly throughout the year. They troubleshoot a lot and generally make sure that their accounts are happy.

VPP: Sounds pretty straightforward. And how do you know if they’re doing a good job? How do you measure their success?

Manager: We have a performance report that’s generated from our CRM tool. At the beginning of each month, it’s sent to both the senior leadership team and me.

VPP: And what are the key metrics on the report that you find most useful?

Manager: Me? None of them. The numbers on the report aren’t that relevant for me or my salespeople. They’re really just for the leadership team to see.

VPP: I’m not sure I understand.

Manager: The numbers on the report are things like Volume of Sales Calls Made, Length of Sales Cycle, and a bunch of other stuff that doesn’t really apply to my group. They might be relevant for some of the other sales groups that have territory managers or whatever, but they don’t help me manage my people any better.

VPP: Then why do you report a bunch of numbers that aren’t relevant to your salespeople?

Manager: Our leadership team wants to have a single set of metrics that they can use to track our company’s performance. I suspect that for most of our sales forces, these metrics work just fine. But my folks don’t need to make hundreds of sales calls, and they don’t really have sales cycles in the traditional sense. So I collect my own set of metrics that I keep in a separate spreadsheet.

VPP: You have your own sales metrics that you use to Manage Your Sales Force?

Manager: Yes.

VPP: Wouldn’t your leadership team be interested to see the metrics that are actually important to your team’s success?

Manager: No. I’ve asked them about it several times, but they seem intent on managing the entire sales force the same way. Honestly, I don’t think they really understand what goes on in my group, since it’s so unlike the other parts of the organization—which is a little ironic, since a high percentage of our overall revenue comes through my team. I guess as long as the top-line number looks good, they don’t really care about the other metrics. Regardless, I have the metrics I need to manage my salespeople, and they have a handful of meaningless reports.

This sales manager inherently understood that different selling roles follow different sales processes, and consequently they require different performance metrics to manage them effectively. Meanwhile, the leadership team unintentionally demonstrated that attempting to measure and manage salespeople with a set of irrelevant metrics creates noise on the war room wall and discontent in the field. In this case, the company was lucky to have an enlightened manager who took it upon himself to measure and manage his team appropriately. Unfortunately, not all companies are this lucky.

As this example illustrates, companies don’t need sales processes; individual selling roles do. Attempting to manage an entire sales force in a uniform fashion neglects the unique activities of each sales role and diminishes management’s effectiveness. His team needed an Account Management process—not the Territory Management process that was being used by his peer groups. So he abandoned the “company” sales process and effectively implemented his own. OK, not necessarily a tragedy. But it is a tragedy that his leadership team was in a war room somewhere staring at useless data on their wall. They had no visibility into the actual inner workings of his sales force, and they certainly had no control over his team’s sales performance. Lots of data, no control.

So when someone asks, “Which sales process is best for our company?” he is asking the wrong question. The first question to ask when you begin to build or rebuild the foundation of your sales force is:

![]() Which distinct selling roles are at work in our sales force?

Which distinct selling roles are at work in our sales force? ![]()

Answering this question will allow you to identify the nature of each selling role and to pinpoint the activities that drive success in each. With the roles and activities clearly defined, you can then turn to the more tactical question:

![]() What is the best sales process to measure and manage each of my selling roles?

What is the best sales process to measure and manage each of my selling roles? ![]()

Answering this question will allow you to select the right sales processes to take control of your sales force’s performance. Failing to answer this question will lead to two predictable situations—neither of which you will want to endure (see Figure 6.2).

FIGURE 6.2 The Impact of Selecting the Right (or Wrong) Sales Processes

The first thing that predictably happens when a mismatched process is forced onto a selling role is exactly what happened in the previous example—it will be ignored. So often when we hear executives grumble about low process adoption by their sellers, we discover that an irrelevant process has been dropped on top of a helpless sales role. Even if a territory manager wanted to use an Account Management process, he’d struggle to make it work. The struggle is usually fairly short, though, and the territory manager will minimize the process to the point of abandonment. It’s often not the salesperson’s fault that the process isn’t being used. It’s just the wrong process.

The second predictable consequence of an errant process implementation is that management will begin to exert effort trying to force compliance by the sellers. We’ve seen management spend an insane amount of time trying to train, deploy, retrain, and redeploy sales processes and supporting tools that will never be adopted—not because the training or deployment was botched, but because it botched the process selection. Implementing a formal sales process is not a trivial endeavor, and the greater the initial investment, the more intensely management wants it to pay off. It fights the battle with great energy, but the battle was lost before it began.

We once witnessed a tragic instance when both of these consequences were suffered by a well-intentioned management team. The company began its tragedy by implementing a Call Management process that it was convinced was needed by its territory sales reps. Unfortunately, the reps found no value in the process and immediately disregarded it. Realizing that the process implementation was a failure, the management team regrouped to assess what had gone wrong. Rather than reaching the proper conclusion that they had deployed an inappropriate process, they determined that the manual call planning activities were too burdensome on the reps, so they needed to automate the process within their CRM tool. Thus began an IT development project that would cost several hundred thousand dollars. Six months later, still no usage by the sales reps. Big investment, no adoption. Even bigger investment, still no adoption. All brought about by a fundamentally mismatched sales process.

In short, don’t make the classic mistake of foisting formal processes on your sales force without vetting the individual selling roles and their critical Sales Activities. If you get a sales process implementation wrong, you could suffer through the mistake for years to come. But if you get it right, you’ll enjoy a degree of control that will not only be evident in the war room, it will also be evident in the field. You will have a perfectly aligned sales management model.

Identifying Your Sales Roles

Your first step on the path to control is therefore to clearly delineate the various selling roles that reside within your organization. This is usually a relatively simple task, since distinct roles frequently have different titles and reporting relationships from one another. However, this is not always the case—particularly in companies that have merged or acquired other companies in the past. There can be a jumble of dotted lines and ambiguous titles that disguise the true nature of the selling roles. In those cases, you must look beyond the job title and org chart to assess what the sellers actually do.

There are an infinite number of ways to define selling roles, and we will not try to characterize every possible distinction. Here, common sense should prevail. But here are some typical reasons that sales roles are separated:

Different Customer Focus

![]() New vs. existing customers

New vs. existing customers

![]() Large vs. small accounts

Large vs. small accounts

![]() High-priority vs. low-priority targets

High-priority vs. low-priority targets

![]() Executive vs. low-level buyers

Executive vs. low-level buyers

Different Product Focus

![]() High- vs. low-tech products

High- vs. low-tech products

![]() Stand-alone vs. bundled products

Stand-alone vs. bundled products

Different Buying/Selling Processes

![]() Consultative vs. transactional sales

Consultative vs. transactional sales

![]() Long vs. short sales cycles

Long vs. short sales cycles

![]() Government vs. corporate buyers

Government vs. corporate buyers

Different Role in the Sales Cycle

![]() Lead generation vs. opportunity follow-up

Lead generation vs. opportunity follow-up

![]() Opportunity managers vs. subject matter experts

Opportunity managers vs. subject matter experts

Whatever the drivers of role distinction in your organization, you must ask yourself, What do these people actually do? What are their objectives, and what are their critical day-to-day selling activities? For example, two people with different titles who are both charged with canvassing a moderate number of existing customers may actually fit into a single “role” for the purposes of sales process selection. One client of ours had acquired numerous companies over the course of a decade, and it claimed to have more than 100 different roles in its sales force. We’ll admit that there were probably 100 different titles on their business cards, but the actual number of distinct roles in play was fewer by an order of magnitude.

Alternatively, two people with the same title may really represent different roles. If one “account manager” makes hundreds of outbound phone calls per month, while another conducts only a handful of face-to-face meetings, we’d have to conclude that these are distinct roles engaged in quite different day-to-day activities. Therefore, we would distinguish between the two when determining which sales processes would be most appropriate to measure and manage their performance.

Regardless of nominal titles and organizational relationships, you need to assess which distinct selling roles reside in your organization before you can proceed to process matchmaking. Companies don’t need sales processes—individual selling roles do. If you try to layer the same process on top of sellers with different tasks before them, at least one of the groups will end up resenting the process and potentially you, as well. Either way, you’ll have made no forward progress toward a more manageable sales force.

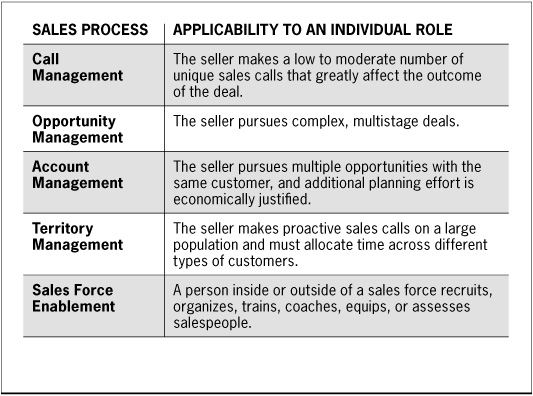

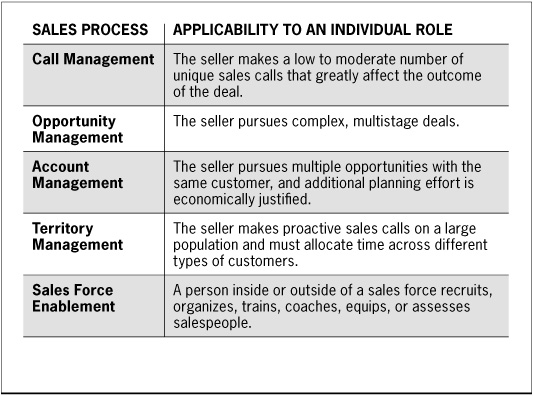

Who Needs a Process?

Once you have identified the nature of the roles in your sales force, the next step is to select the specific sales processes that are most appropriate for each. In the previous chapter, we shared how categorizing the Sales Activity numbers on our war room wall had revealed five discrete sales processes. By examining the metrics and what they were intended to measure, we were also able to deduce the key activities and goals of each process. As we considered these activities and goals in even greater depth, we were able to identify the context in which these processes are the most useful. We will now explore these situations, because if you understand the contextual value of each sales process, it will become apparent to you which of the processes your selling roles require.

![]() Call Management. Remember that a Call Management process is intended to improve the quality of individual customer interactions through the thoughtful planning of a sales call. This helps a salesperson preview the upcoming interaction, identify desired outcomes, anticipate the conversation, and generally plan for any contingencies that might be reasonably predicted. While Call Management demands a higher investment in call preparation, the extra effort pays off when the seller is able to safely maneuver the inevitable zigs and zags of live contact with a customer.

Call Management. Remember that a Call Management process is intended to improve the quality of individual customer interactions through the thoughtful planning of a sales call. This helps a salesperson preview the upcoming interaction, identify desired outcomes, anticipate the conversation, and generally plan for any contingencies that might be reasonably predicted. While Call Management demands a higher investment in call preparation, the extra effort pays off when the seller is able to safely maneuver the inevitable zigs and zags of live contact with a customer.

At its heart, call planning is about gaining control of a potentially messy situation. It’s about anticipating the expected and the unexpected things that could occur during the call and then preparing yourself to handle them both tactically and emotionally. It is about charting the course that you want to take during the call and then trying to remove as much uncertainty and risk as possible. It enables you to proceed confidently but with a healthy dose of caution.

So to understand when Call Management would be an appropriate sales process, we asked ourselves, What type of sales call would warrant such caution on the part of the seller? The obvious answer is a call for which a negative outcome will have a meaningful and unwanted consequence on the sale. There must be some gravity to the sales call, or else a salesperson could leave the outcome to chance and save herself the extra effort of planning. So foremost, Call Management is a relevant sales process if:

![]() A single sales call can greatly affect the outcome of the sale.

A single sales call can greatly affect the outcome of the sale. ![]()

But wait a minute. Aren’t all sales calls important? If a call isn’t important, then why make it? The truth is, many selling roles are not filled with potentially lethal customer interactions. It’s not that their roles aren’t high-pressure, but many sellers’ day-to-day activities have a high service component or a “stay in front of the customer” mission. Salespeople such as these often have large territories of customers where ongoing relationships take precedence over individual interactions. In sales roles such as these, not every call is a do-or-die situation. These sales-people certainly add value to the customer relationships, but the majority of their activities are relatively low-risk.

In other cases, one bad sales call can kill the deal. This is particularly true for prospecting calls, when a poor outcome typically means that the entire opportunity is dead on arrival. Another example of a high-risk sales call would be one in which you are delivering your final proposal to a major prospect, a situation probably worthy of a little preparation. There are many types of calls that warrant extra precaution, and these are situations in which call planning is an especially good idea.

Another type of interaction that is a candidate for Call Management is a call with a high degree of uncertainty as to how the conversation will unfold. If all of a seller’s calls are very routine with a well-worn agenda, then no preparation is needed. Nearly every call will happen precisely as expected. However, when a call could potentially take many different turns, call planning helps the sales rep anticipate the unexpected—primarily the unpredictable behavior of a customer. Therefore, Call Management is also relevant if:

![]() The content of sales calls is highly variable, and the customer’s behavior is uncertain.

The content of sales calls is highly variable, and the customer’s behavior is uncertain. ![]()

But isn’t every sales call different? If every call were alike, wouldn’t you need an actor rather than a salesperson? Of course every sales call is unique, but to differing degrees. Nearly every salesperson has some calls that they would consider “routine”—the types of calls that they have made many times and are basically the same discussion again and again. A sales rep who makes 100 prospecting calls per week is probably using a similar approach in most of his calls. Not every call will follow the same path, but most of them will. And a territory sales rep who does product demonstrations may give the exact same presentation to every customer. Will the audience respond differently from one instance to the next? Maybe. Will these salespeople need to spend an hour planning for each rote presentation? Maybe not.

But then there are calls that can go in many possible directions. If the prospect or customer is relatively unknown to the seller, the salesperson might need to invest a lot of time beforehand researching the customer and anticipating its needs. Or if a strategic account manager meets with her customer’s executive team only a few times a year, then the conversation is likely to be rich and cover many different topics. This is another situation in which thorough preparation can help the salesperson anticipate the zigs and zags of an uncontrolled interaction. The more varied the content of the call and the less certain the customer’s behavior, the more appropriate Call Management becomes.

One final factor that affects the relevance of Call Management activities is highlighted by the example just given of a seller who makes 100 outbound calls per week. In this case, there is the practical matter that a salesperson making such a high volume of calls cannot realistically plan for all of them, or even many of them. Call planning is a time-consuming activity that can only be employed when the potential payoff exceeds the known cost. Therefore Call Management is also most appropriate if:

![]() The sales role makes a low to moderate number of sales calls.

The sales role makes a low to moderate number of sales calls. ![]()

But what is a “moderate” number of calls? Five in a week? Twenty? Fifty? Clearly there is no right answer—to an extent, it’s all relative. But if a salesperson is asked to create call plans for too many calls, it won’t be long before the exercise becomes administrative and loses its value. Don’t let that happen.

Of course, there is an inverse relationship between the volume of planning a salesperson can do and the level of effort that is put into each planning session. We would argue that a salesperson should never pick up a phone or walk through a door without at least posing a few critical questions to himself, such as, What is my objective? How am I going to open the conversation? and What is the buyer’s motivation to speak with me? But as far as formal call planning sessions go, we’ve seen Call Management have the greatest impact with salespeople who deliberately plan for a few calls each week. If they try to do many more, they become full-time planners rather than full-time sellers. So judgment must be used on the part of sales leadership as to how realistic extensive Call Management is for a particular selling role.

![]() Opportunity Management. An Opportunity Management process is intended to help sellers strategically pursue and win deals that involve complex buying behavior. They force a salesperson to take inventory of all the factors that could influence the deal, like the buying process, its participants, the competitors, and other contextual details. Once the landscape is known, the seller then devises an approach to win the opportunity and executes her plan of attack.

Opportunity Management. An Opportunity Management process is intended to help sellers strategically pursue and win deals that involve complex buying behavior. They force a salesperson to take inventory of all the factors that could influence the deal, like the buying process, its participants, the competitors, and other contextual details. Once the landscape is known, the seller then devises an approach to win the opportunity and executes her plan of attack.

The situation in which a selling role would need to engage in Opportunity Management activities is probably the most apparent of all five sales processes. Opportunities are deals that entail multiple customer interactions before they can be won, as opposed to sales that can be made with a single sales call. Opportunities also frequently involve multiple stakeholders in the buyer’s organization that have different roles in the process and differing agendas. All of this puts pressure on the salesperson to be deliberate in his treatment of the pursuit. Therefore, an Opportunity Management process is relevant if:

![]() The sales role pursues complex, multistage deals.

The sales role pursues complex, multistage deals. ![]()

Again, it’s fairly evident when this is the case. Does the typical sale for the salesperson require multiple sales calls over time? Then the role is a pretty good candidate for Opportunity Management activities. It’s really that simple. But we have a few observations that we should share before we move on.

By definition, an opportunity is an individual pursuit that has a discrete beginning, middle, and end. It pops onto the salesperson’s radar screen as a lead and then proceeds through milestones on a linear path toward an inevitable “win” or “loss.” This is not to be confused with Account Management, for which a salesperson may make many, many calls on a single account in an attempt to sustain an ongoing stream of business. We have known companies to confuse Opportunity and Account Management activities because they can look very similar—a salesperson making multiple calls on various stakeholders in a buying organization. But Opportunity Management is only relevant if the activities surround distinct deals, not ongoing relationships.

That being said, the pursuit of a new “account” can actually be a situation that employs Opportunity Management. For instance, we work with many sales forces whose primary objective is to recruit new customers into long-term relationships. An example would be a product manufacturer that tries to recruit new retail chains to carry its products. Often it will have two separate sales forces—one to sign up the retail chains and another to manage the ongoing relationships. The first sales force is pursuing opportunities, because its sellers are engaged in multistage “sales” that proceed from a lead to a close. An Opportunity Management process would suit them just fine. The second sales force is managing accounts, because its sellers are engaged in retaining and growing existing customers. An Account Management process would be appropriate for them. Despite the fact that the first sales force is chasing “accounts,” its activities look exactly like a sales force that is chasing individual deals. Here an Opportunity Management process will enable better selling.

Finally, unlike Call Management activities that can often only be conducted for a fraction of a salesperson’s calls, sellers frequently have the capacity to apply Opportunity Management activities to all of their deal pursuits. Practically, the level of effort required for opportunity planning is somewhat self-regulated because a seller can only pursue so many deals at once. And the fewer deals she has, the more important Opportunity Management becomes.

![]() Account Management. An Account Management process is used to maximize the long-term value of selected customers. It helps you to align your company’s goals with those of your customer and to find compelling ways to strengthen your business relationship. Recall that the key Account Management activities are assessing your customer’s needs, aligning your goals with theirs, developing an action plan to create mutual value, and executing the items in the plan. Beyond just planning what you want to get from your key customers, a good Account Management process helps you determine what you must give them in return.

Account Management. An Account Management process is used to maximize the long-term value of selected customers. It helps you to align your company’s goals with those of your customer and to find compelling ways to strengthen your business relationship. Recall that the key Account Management activities are assessing your customer’s needs, aligning your goals with theirs, developing an action plan to create mutual value, and executing the items in the plan. Beyond just planning what you want to get from your key customers, a good Account Management process helps you determine what you must give them in return.

So in what situation would an Account Management process be appropriate for a given selling role? That is, who would want to invest an additional level of effort in bolstering certain customer relationships? Obviously, this process would be irrelevant for a salesperson who did not call on existing customers. By definition, Account Management activities are focused on customers with ongoing relationships that lead to repeated purchases over time. Therefore, an Account Management process is relevant if:

![]() The seller pursues multiple opportunities over time with the same customer.

The seller pursues multiple opportunities over time with the same customer. ![]()

Many salespeople never see a repeat customer. In some cases, their role is defined as such—they are “hunters” who are exclusively focused on acquiring new customers for their companies. If there are additional opportunities to pursue after the initial sale, other sales roles in their organization will take ownership of the account. In other instances, a company may not have the product breadth to up-sell or cross-sell to its customers. Its salespeople make one sale to a prospect and then move on as a practical reality. Either way, these roles would have no use for an Account Management process.

On the other hand, many salespeople engage the same customers again and again in attempts to sell, resell, cross-sell, and up-sell additional products and services into those accounts. Their customers and prospects are the very same targets, and leveraging their existing relationships is their primary go-to-market strategy. In situations like these in which the salesperson’s role is to retain and grow an established base of customers, Account Management activities are highly pertinent.

But the fact that a sales role calls on existing customers is not sufficient to justify a full-blown Account Management process. Proactively managing customer relationships requires a meaningful investment on the part of the selling organization. Salespeople can spend days, weeks, or even months developing and executing a robust account plan. Therefore, Account Management activities are only warranted if:

![]() There is an economic justification for the additional level of effort.

There is an economic justification for the additional level of effort. ![]()

Plenty of salespeople call on existing customers but need not engage in formal Account Management processes. A classic example would be a territory sales rep who calls on hundreds of different customers during the course of a year. Each of her individual customers contributes a small amount of economic value, but in sum her territory yields a sizable profit. Sales roles like these target existing customers exclusively, but “managing” their individual relationships would not be worth the incremental effort required. These are efficiency-driven roles, and customer visit frequency takes precedent over customer intimacy.

However, when a salesperson services only a few customers or his profits are highly concentrated in a small number of accounts, it’s well worth the investment of resources to ensure that these customers are nurtured and fed. The economic impact of losing an account could be felt across an organization, and the opportunity for growth with these customers is often great. Aligning your company’s goals with theirs and paying close attention to the relationship is a wise thing to do. An Account Management process is the perfect fit for sales roles that find themselves with these types of customers.

![]() Territory Management. A Territory Management process is intended to help salespeople allocate their time most efficiently across a large group of assorted customers and prospects. By forcing sellers to prioritize their customers and execute their call patterns accordingly, this set of activities makes certain that your sales force’s effort is directed at your preferred types of customers. Unlike the three previously discussed processes that boost salesperson effectiveness, Territory Management activities help drive organizational efficiency.

Territory Management. A Territory Management process is intended to help salespeople allocate their time most efficiently across a large group of assorted customers and prospects. By forcing sellers to prioritize their customers and execute their call patterns accordingly, this set of activities makes certain that your sales force’s effort is directed at your preferred types of customers. Unlike the three previously discussed processes that boost salesperson effectiveness, Territory Management activities help drive organizational efficiency.

What type of sales role, though, would not benefit from using a Territory Management process? Couldn’t every salesperson profit from more efficient allocation of sales calls? No, not really. Believe it or not, many salespeople are not in control of their calling patterns. Some receive inbound phone calls, and others are given leads on which they follow up. They don’t choose when and where to focus their effort, because their effort is focused by design. Therefore, a Territory Management process is only relevant if:

![]() The sales role makes proactive outbound sales calls.

The sales role makes proactive outbound sales calls. ![]()

For Territory Management activities to have relevance for a salesperson, she must be in control of her own schedule. If the seller is receiving sales calls rather than proactively making them, then the concept of prioritizing her effort is rendered useless. Or if the person is primarily in a supporting role, such as a subject matter expert, she may be called upon only as needed by the frontline sellers. There are actually plenty of roles in sales forces that are reactive in their stance. For these roles, Territory Management is an unnecessary exercise.

Of course, most salespeople do manage their own schedules and allocate their own effort, so does that mean that every salesperson who is in control of his own calendar should employ Territory Management activities? No, it doesn’t. Since Territory Management is a process for allocating effort, it’s only valuable if a salesperson has too little time to fully service all of her assigned accounts. If a rep can comfortably lavish attention on all of her accounts, she wouldn’t need to ration her effort. Therefore, Territory Management activities are most relevant if:

![]() The seller is assigned too many customers to fully engage them all.

The seller is assigned too many customers to fully engage them all. ![]()

A major account manager may be responsible for only a handful of customers, or even a single account. If so, she will be able to invest whatever effort is necessary to maximize the value of each customer. However, if a salesperson is assigned 200 accounts, there is an implicit expectation that she will attend to some of those customers with a greater intensity than others. In this case, Territory Management is a necessary endeavor if any of the accounts are to be served sufficiently. Without a deliberate plan for how the seller will allocate her time most appropriately, all of the accounts will likely be underserved.

There is one final condition that must be met for a Territory Management process to be most meaningful. At its best, Territory Management is not only about making as many sales calls as possible—it’s about making the right types of calls on the prospects and customers with the highest potential value. This, of course, assumes not only that you’ve identified your high-value customers but also that you want to attend to them disproportionately. Consequently, Territory Management is particularly valuable if:

![]() You want to treat different types of customers differently.

You want to treat different types of customers differently. ![]()

If all of your prospects and customers have equal value in your company’s eyes, then a Territory Management process would be an unnecessary level of rigor in forming your call patterns. You wouldn’t need to emphasize one group of customers over another, so you could simply design your salespeople’s territories such that they have enough time to call on all of their targets with your preferred frequency. Therefore, Territory Management activities are only worthwhile if you want to discriminate among different types of customers and over-allocate your effort toward those that are most desirable.

![]() Sales Force Enablement. Sales Force Enablement activities are intended to increase the sales force’s ability to execute the previous four processes. But unlike Call, Opportunity, Account, and Territory Management activities, Sales Force Enablement is a collection of management decisions that are primarily the domain of sales leadership. Whether it pertains to recruiting, organizing, training, coaching, equipping, or assessing salespeople, management must decide how to invest its resources to make the biggest impact on sales force performance.

Sales Force Enablement. Sales Force Enablement activities are intended to increase the sales force’s ability to execute the previous four processes. But unlike Call, Opportunity, Account, and Territory Management activities, Sales Force Enablement is a collection of management decisions that are primarily the domain of sales leadership. Whether it pertains to recruiting, organizing, training, coaching, equipping, or assessing salespeople, management must decide how to invest its resources to make the biggest impact on sales force performance.

Also unlike the other sales processes, Sales Force Enablement is compulsory. You don’t look at sales management and ask, “Should it be enabling the sales force?” It is unquestionably the role of every sales manager to enable better execution by the sales force. However, the breadth of the Sales Force Enablement activities is great, and responsibilities for each could be distributed across several different roles in an organization, even business functions outside of sales like human resources or finance. So rather than asking in what situation Sales Force Enablement activities would be relevant for your sales force, the real question to ask is:

![]() Which roles should be responsible for performing these specific activities?

Which roles should be responsible for performing these specific activities? ![]()

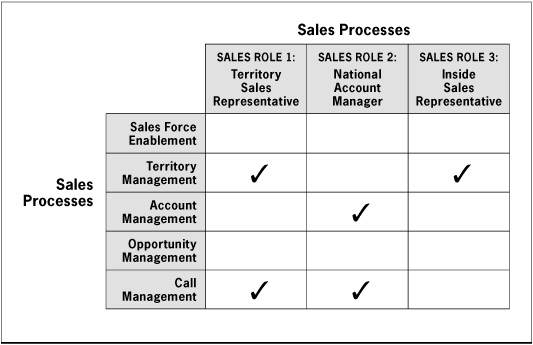

We will not attempt to answer this question because it can only be answered in the context of your own organization (see Figure 6.3). Depending on how your company is structured and where the competencies reside, responsibility for these activities could belong directly in your field sales force, in a sales operations group, in another business function, or even with an external partner completely outside of your company. The goal is to find the most qualified resources for the specific Sales Force Enablement activity in question.

FIGURE 6.3 The Relevance of Particular Sales Processes to Different Selling Roles

If your human resources department doesn’t recruit the best salespeople, then don’t let it recruit for you. If your corporate training group doesn’t have the best sales trainers, then don’t let it train. If your sales managers aren’t the best coaches, then give us a call. Sales Force Enablement activities are too critical to a sales force’s performance to have them reside in a place of convenience. You need to identify the most capable resources to enable your sales force and then point them toward very specific outcomes. With focused effort by best-in-class resources, your sales force’s ability to execute its key activities can increase dramatically.

Process-Role Matchmaking

Now that you have your sales roles clearly delineated and some guidelines for which sales processes could be relevant for each, it’s time to play matchmaker. As you might have concluded reading through the preceding paragraphs, picking the right processes for each selling role is not always a straightforward feat. Often, there is more than one process that aligns with a particular sales-person’s job description. Unless your sales roles are very narrowly defined (which is not a bad thing), you will find that their daily activities capture elements of multiple sales processes.

For instance, you may have a role in your sales force that is responsible for prospecting within a region (Territory Management) and then pursuing the multistage deals that are uncovered (Opportunity Management). In another case, you may have sellers responsible for servicing dozens of small customers (Territory Management) as well as maintaining a handful of strategic accounts (Account Management). And in either case, the nature of their sales calls may warrant Call Management activities. It’s easy to see how a salesperson’s day-to-day activities can be reflected in more than one sales process, and you might need to employ more than one process to measure and manage them effectively.

To assess which processes you should have in your own sales force, create a chart like the one in Figure 6.4. This will help you identify your individual selling roles and take inventory of the formal processes that might be relevant to each. This example comes from a past client of ours that we took through a similar exercise.

FIGURE 6.4 Sales Process to Sales Role Map

The most prevalent role in our client’s sales force was the territory sales rep, who was responsible for canvassing particular geographic territories. Territory sales reps contacted both small and large customers with varying frequency, and their calls on the larger accounts were highly varied interactions that required careful planning to conduct effectively. Therefore, Territory and Call Management were deemed necessary for this role.

Our client also had a national account manager role who was responsible for growing relationships with large accounts strategically important to the company. The interactions with these accounts took place at very high levels in the customers’ organizations, so extensive preparation was required for each sales call. Therefore, Account and Call Management processes were considered highly relevant for this particular role.

Finally, the sales force had inside sales reps that made outbound calls for both prospecting and customer service purposes. With a database of several thousand customers and prospects, it was important for the inside sales reps to focus their attention on their highest-priority targets. Consequently, Territory Management activities were a must. However, the content of the phone calls was typically scripted, so Call Management was less relevant for this role than for the Territory Sales Rep or National Account Manager.

Most people we take through this process-role matchmaking exercise will have one of two reactions. The first reaction is, “Well, it looks like my sales processes are all messed up.” For example, a company with identical roles to this client might have implemented a Call Management process across its entire sales force, which would be irrelevant for its inside sales reps. And the client might be missing Territory and Account Management processes, which would hinder its ability to measure and manage its territory and account managers. In cases like these, there’s an obvious mismatch between the nature of the selling roles and the sales processes in place.

The second reaction we hear is, “You know, it looks like my sales roles are all messed up.” This can occur when people realize the complexity of what they are asking their salespeople to do. Regardless of which formal sales processes the company has in place, this matchmaking exercise can reveal the breadth of activities that are designed into individual selling roles. For instance, we know a sales force with a single role that was accountable for generating leads by phone, servicing large numbers of small customers in the field, and managing a group of key strategic partnerships. Examining the role from a process-driven perspective led managers to say, “Wow. We are asking these people to do so much, it’s unlikely that they’re doing any of it as well as possible. Maybe we should split this job into two or three different roles, so our salespeople can do fewer things with greater focus.” To which we responded, “That might be a good idea.”

Whether you discover that your sales processes are mis-aligned or your selling roles are ill-defined, it’s rare that we find sales forces with perfect harmony between the two. Salespeople’s responsibilities and formal sales processes often change over time, so they can slowly drift apart. Given that reality, it’s smart to take a periodic look at what your salespeople are actually doing and which processes you have in place to manage them. Again, when the wrong processes are imposed on a sales force, it not only causes a sense of frustration in the field, it causes a lack of control in the war room. Putting the right levers and pulleys in place is a crucial step along the path to proactively managing your sales force’s performance.

Too Much of a Good Thing

When you finish mapping your relevant sales processes to your individual selling roles, you may look down to find that a single role does have three, four, or all five sales processes selected.1 In fact, most roles in your sales force are likely to have multiple processes in play unless you’ve defined the roles very narrowly. So if you do have complex roles that demand layers of sales process, is it wise or even reasonable to impose such rigor on a sales force? Will too much of a good thing turn your building blocks into a suffocating procedural nightmare? We think not.

Foremost, this matchmaking exercise may have uncovered an opportunity to simplify the roles in your sales force. If your salespeople are being asked to do too much, it’s quite possible that they’re really doing too little. We were once conducting a public workshop where we asked the attendees to map these processes to their existing roles, and one sales manager declared, “When I get back to the office next week, the first thing I’m going to do is to reassign half of the activities that my salespeople currently have in their job description. I can now see that they need to be focused on executing one sales process to the highest degree rather than half-executing several.” Brick-meet-forehead moments like this are more common than you might think, and we expect that most salespeople welcome the simplified life.

Generally speaking, we see a trend toward sales forces having a greater number of more specialized selling roles. Management long ago began to separate “hunters” from “farmers,” but the number of boxes on the frontline org chart continues to grow. From industry specialists, to product experts, to sellers who serve niche markets, the roles we find in sales forces are becoming more diverse in nature and more narrow in scope. This not only makes the seller’s tasks easier to master, it also reduces the management challenge of hiring, developing, measuring, and compensating complex roles.

However, some selling roles are inherently multifaceted and incapable of being simplified without compromising their efficiency or effectiveness. In these cases, you can attempt to prioritize the relevant processes and eliminate any that aren’t critical to the role. You would do this by establishing the strategic importance of each selected process, as well as its impact on your ability to adequately measure and manage those salespeople.

For instance, you may have a role in your sales force that’s primarily focused on servicing your largest customers. An Account Management process would be critical. Those same sellers may also maintain a smattering of small accounts that they call on periodically because they’ve done so historically and it requires relatively little effort. At first glance, Territory Management activities could be desirable for this role—the sellers are allocating their time across different types of customers. But after deeper consideration, you might ascertain that these small accounts matter very little to the bottom line of your company, and the threat of their monopolizing your account managers’ time is low. In this instance, you could decide that Territory Management wouldn’t be worth the investment of resources, since it would have little impact on your Business Results or your ability to manage the role. Life simplified.

Alas, you will often have roles in your sales force that cannot be simplified by peeling away layers of sales process. Multiple processes may be required in order for sellers to sell productively and for you to manage proactively. In these cases, ignoring Territory Management would put your sales force at risk for misallocated effort, neglecting Account Management would threaten a large portion of your business, and disregarding Call Management would hinder your team’s effectiveness. There’s little else you can do except to find a way to implement the formal sales processes in the least intrusive fashion.

But there is hope that you and your salespeople can maintain sanity in a process-heavy environment. As a practical reality, each of the sales processes operates with a different cadence and consumes resources in different ways. For example, Call Management activities are most likely a weekly occurrence for sales roles that engage in that process. But Account Management activities are more episodic, commonly revisited quarterly or monthly.2 And the highly analytic Territory Management tasks of prioritizing customers and designing call patterns can be performed somewhat infrequently by management, sales operations, or even marketing. All sales processes have implications for the day-to-day activities of a sales force, but they don’t all impose day-to-day demands on its time.

We work with many sales forces that have several formal sales processes deployed in the field. It is neither impossible nor impractical to do so once you’ve determined which sales processes will help you attain your Business Results more predictably and manage your salespeople more productively. When you know which processes need to be in place, the question you face is no longer, Should I implement formal sales processes? The question becomes, How do I implement processes that yield the greatest organizational benefit with the least disruption to my sales force? Then you can set about the task of “rightsizing” your formal sales processes.

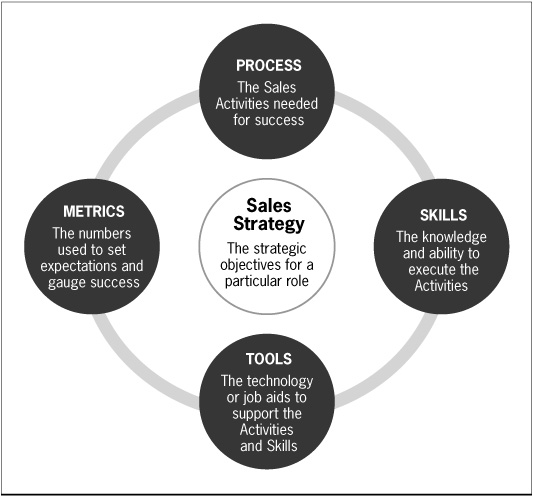

RIGHTSIZING YOUR SALES PROCESS

Implementing a new sales process is no trivial affair. To receive the maximum business impact from the new process, you must approach the implementation effort from an overall change-management perspective. It involves more than just directing the sales force to engage in different types of activities—it also requires you to alter the environment in which the activities take place. Management guru W. Edwards Deming is credited with saying that “A bad system will beat a good person every time,” and nowhere is this more true than in a sales force. If you don’t support your desired behavioral changes with new metrics, tools, and skills to reinforce and measure the change, your sales force will quickly revert to its previous state. Lasting change is hard to affect, and there are substantial organizational costs to properly deploying a formal sales process.

Therefore, it’s critical to determine how much change is actually needed in order to reap the benefits of the new sales process. If you’ve selected the right processes for your individual selling roles, all that stands between you and a highly manageable sales force is the right-sized implementation plan. When we see process implementations fail to deliver their anticipated results, it’s often because the scope or scale of the change effort was miscalculated by management. Let’s examine two ways that formal sales process deployments get botched.

One classic management blunder is to underestimate the amount of change required for a sales force to adopt a new process. Anemic implementation efforts are analogous to pushing your finger into an inflated balloon. The balloon’s shape temporarily complies with your wishes, only to return to its original form once you remove the direct pressure. And so goes the sales force. When too little change-management effort is applied to the sales force, it will comfortably return to business as usual at its first opportunity. In fact, salespeople have told us to our faces that their new sales process was just another “flavor of the week” project to be ignored. They declared that if they avoided the process long enough, it would eventually go away. Balloon, meet finger.

Candidly, management often overestimates its ability to direct changes in its sales force. For example, we’ve known sales leaders to send memos to the field announcing substantial process changes, expecting the new process to be strictly followed by the end of the day. We’ve also known leadership to distribute new call planning tools during regular sales team meetings, expecting them to be dutifully incorporated into the sales reps’ everyday routine. It should come as no surprise that these war room directives failed to take root in the field. Their “change management” efforts yielded zero return on a meager investment.

“Wait a minute,” you might be thinking. “Didn’t I read earlier in this very book that sales managers should be able to direct their sales forces’ activities?” Yes, a fundamental tenet of this book is that sales managers can direct Sales Activities and change all of the numbers on their war room walls, which is absolutely true. But it requires more than the spoken word to alter deeply ingrained behaviors—it requires a more holistic approach to change management. Sustainable changes in behavior are achieved only if the entire system surrounding the salesperson is designed to support and reinforce the desired behaviors. Otherwise, inertia and lack of focus will outlast the change effort, and it will eventually go away.

Ironically, the second way that management can doom a sales process is to overengineer it. Unlike the first situation in which inadequate investment leads to process abandonment, here we witness change efforts that are overly ambitious and attempt to pull salespeople too far away from their natural selling rhythm. Ideally, any sales process you implement would simply put structure and rigor around the activities that your salespeople should already be doing. When a good sales process is deployed, you will often hear comments like, “Yeah, I already do this, but probably not as well as I could,” or “I used to do this all the time, but I kind of got away from it.” These comments show that the salespeople see value in the process because it’s congruent with the way they actually sell. You may still encounter implementation challenges, but they can be overcome with persistent reinforcement.

More difficult challenges are created when the new process or supporting tools complicate the seller’s world beyond what seems reasonable to them. For instance, a salesperson may acknowledge that a Call Management process would help her conduct more effective sales calls, particularly when calling on new prospects. If that’s the case, then you would probably succeed in deploying a process with that specific scope. However, the sales force might reject the process entirely if it was expected to complete formal call plans for every single customer interaction. The process would seem burdensome and perhaps legitimately overbearing.

Another example of overengineering that we frequently observe is a super-sized Account Management process. Again, your sales force may agree that it could do a more thorough job of engaging its top accounts and aligning with its customers’ objectives. If so, it might welcome an Account Management process that forces just a little more structure and rigor in this area. However, a 20-page account plan that requires salespeople to document everything they know about the account would immediately be rejected as a low-value administrative task. And perhaps it would be. If that level of effort is well beyond what sellers perceive as reasonable, then the process will be resented and never usefully adopted.

Of course, we aren’t proposing that a sales force’s unanimous consent is required for leadership to design and implement a sales process. Many unpopular edicts are still good management decisions. Our point is that it’s necessary to find the right level of effort between inadequate change management and process overkill. Either extreme will render an otherwise perfect sales process highly irrelevant to the sales force (see Figure 6.5). It will become yet another flavor-of-the-week project that is ignored until its death.

FIGURE 6.5 Rightsizing Your Sales Process

Our own approach to change management can be best described as comprehensively minimalist. As we just mentioned, we feel very strongly that when you implement a sales “process,” you must also consider the comprehensive system in which the salesperson operates (see Figure 6.6). We always begin by considering the strategy—in this case, how the individual role is defined and what it is intended to accomplish within the context of the larger sales force. We then design the process itself, which is the collection of key selling activities that must be performed. We then examine the tools that are required to support the sales process, as well as the skills that are needed to successfully execute the activities. Finally, we develop a set of metrics that will enable the effective measurement and management of the process. This holistic approach to change management enables sustainable change through multifaceted design, training, and reinforcement.

FIGURE 6.6 A Comprehensive Approach to Change Management

While our approach is comprehensive in scope, we try to deploy the minimal amount of rigor required to accomplish the process’s objective. The scale of an Account Management process for a sales rep with 10 large customers assigned to him would be dramatically smaller than a situation in which 10 salespeople were assigned to a single account. And the Territory Management demands on a salesperson with 50 medium-sized customers could be much less intense than those on a rep with 500 prospects spanning various industries, geographies, and sizes. Overkill and under-kill are equally as deadly when it comes to change management. If the building blocks of control are too big or too small, anything resting on them is at risk. Rightsizing your sales processes and the related implementation effort is critical to successful sales management.

OFF THE SHELF OR OFF THE MARK?

We mentioned that we are often asked, “Which sales process is best for our company?” With almost equal frequency, we field a similar question: “Which sales process is a best practice?” As you know, our response to the first question is that you don’t assign processes to companies—you assign them to individual selling roles. Our answer to the second question is that the best-practice sales process is the one that is right for the role, properly sized, and resides within a system that supports and reinforces it. Probably no surprises there.

But when people pose these two questions to us, they frequently aren’t asking us to choose between the Call, Account, Opportunity, Territory, and Sales Force Enablement processes that our research revealed, because not many people have ever viewed sales processes through this lens. More commonly, they are asking our opinion on the various sales methodologies that can be licensed in the marketplace. These are predefined processes that come fully cooked with discrete sales activities baked right in. Need a Call Management process? Got one right here.

Numerous vendors offer off-the-shelf sales processes for purchase, most commonly different flavors of Call, Account, and Opportunity Management. We ourselves have standardized frameworks that we often use as platforms for highly customized implementation efforts. And in fairness to them all, no process, whether off the shelf or built from scratch, is inherently good or bad. The inherent value of any process is completely contextual.

Earlier, we defined a “best practice” sales process as one that

1. is relevant to the role

2. is properly sized

3. resides within a system that supports and reinforces it

It’s easy to see where any off-the-shelf process might deviate from this formula. Foremost, the relevance of a process to a role is not necessarily a process vendor’s first priority. If the vendor only offers a Call Management process, it’s likely that it will try to sell you a Call Management process. And not necessarily because the vendor is dishonest or deceptive—that’s just its perspective on the world. If you need such a process, then you are on a path to best practice. But if the sales role in question actually manages a vast geographic territory and makes fairly homogenous calls, a Call Management process would be rejected, and your investment would bear no return. When we find irrelevant processes in place, it’s often because of an “I have a hammer, you must be a nail” vendor interaction.

Second, we’ve never met a one-size-fits-all sales process. The importance of deploying the proper level of rigor in a sales process cannot be overstated, and off-the-shelf processes are commonly engineered to the greatest possible degree. It’s not uncommon to find 10-page account plans sitting unused on the shelves of account managers who are tending to 20-plus accounts. There’s no way they’re going to undertake such an effort for dozens of accounts, and they probably shouldn’t. For some sales roles, 10 pages would be just the right amount of account planning effort. For others, 1 or 2 pages might more closely reflect the true need for Account Management rigor. If you’ve ever been a 2-page variety of account manager forced to complete a 10-page account plan (and we have), then you will appreciate the eagerness with which a salesperson will abandon the process.

Finally, it’s extremely difficult to integrate a prepackaged sales process into a complex selling environment. Recall that a process needs to be supported by associated training, tools, and metrics to have any chance at sustainability. Many process vendors will include training and tools that wrap around their specific process, but the alien process/training/tool bundle is usually too detached from the rest of the seller’s world to find its place in her day-to-day activities. The process will feel clunky and awkward in the field, and the body will reject the unfamiliar transplant. Of the three conditions that we propose for a best-practice sales process, this is the least likely to be satisfied by an off-the-shelf product.

In brief, off-the-shelf sales processes can be perfectly on target with the needs of a particular selling role, sometimes. They can also miss the mark by so much that they are less than worth-less—they are a drag on sales force productivity. Whether you choose to build or buy your formal sales processes, you must make sure that they are the right size and shape for your particular roles and that they are integrated into a comprehensive change management framework. Only then will you have the right building blocks in place to effectively measure and proactively Manage Your Sales Force.

DOES THAT ALSO COME IN GRAY?

There’s one final point that we need to make about the nature of sales processes, and it’s that there are many different varieties of each. That is, you can buy or build many different types of Call, Opportunity, Account, and Territory Management processes, depending on what your salespeople are trying to accomplish. The key is to understand the underlying methodology of each variation and select the flavor of process that’s appropriate to your task. Let us use the Call Management process to illustrate this, since it’s one of the most widely used sales processes.

All Call Management processes are intended to accomplish the same thing—to increase the quality of an individual customer interaction. However, salespeople make different types of sales calls, and the particulars of a Call Management process should mirror the particulars of the call that it’s being used to improve. For example, the goal of a sales call early in the sales cycle is usually to uncover a customer’s needs and motivate him to take action. In these calls, a Call Management methodology that’s designed to explore a prospect’s situation or build perceived pain would be extremely valuable.

However, once the customer has acknowledged his need and proceeded deeper into the buying process, a Call Management methodology that’s focused on exploring needs and building pain becomes irrelevant. A Call Management methodology that emphasizes “gain” would be a better choice, since the seller’s task later in the sales cycle is to paint a pretty picture of the prospect’s future—not to continue building dissatisfaction and discomfort for the buyer.

An even more specific type of Call Management process would be one that’s used to prepare a seller for an upcoming negotiation. The goal of that customer interaction is neither to build pain nor to project gain, but to reach a mutually beneficial agreement on a particular issue like the purchase price or some other characteristic of the deal. In that situation, a Call Management methodology that is designed to help the seller prepare for the give and take of negotiation would be the most valuable framework.

In all three of these examples, we are discussing Call Management processes. One is used to expose pain, one to magnify gain, and another to negotiate the finer points of a deal. Though these distinctions may seem subtle, they can have a huge impact on the potency of your sales process. We’ve witnessed many salespeople still churning up pain deep into a long sales cycle, just because that’s what their Call Management methodology instructed them to do. Conversations like that not only frustrate the seller, they also confuse the buyer. Neither outcome is desirable.

So once you’ve identified a process that you need for a particular role in your sales force, your process selection venture is not yet complete. You also need to examine the precise selling tasks of the role and find a process methodology that’s right for the job. Choosing a sales process is not always a black-and-white decision—every sales process comes in several shades of gray.

STATUS CHECK

As we began to consider how a leader would use the new sales management code to increase control over sales performance, we put a sharp eye on the highly manageable Sales Activities and the five formal processes that encompass them all. These processes are the fundamental building blocks of control over your sales force because they provide your managers with the tactical gears and levers they need to effect behavioral change in the sales force. In the absence of formal sales processes, management’s task is reduced to asking for desired Objectives and Results without the means to influence them. With sales processes, managers actually have something to manage.

We then explored the relevance of each sales process to any given sales force and concluded that relevant processes can only be determined by examining the actual activities of individual selling roles. Our insight: the nature of each role determines which processes should be deployed in your sales force. Choosing the right sales process is actually an exercise of matchmaking your individual roles with the five sales processes. This act of selecting the right processes is the key step to gaining adoption by your salespeople. See Figure 6.7.

FIGURE 6.7 The Relevance of Particular Sales Processes to Different Selling Roles

In addition to selecting the right processes for each role, our experience has shown that there are two other conditions for the successful deployment of a formal sales process. One condition is that the process must be sized appropriately for the role. If a process is too rigorous for the day-to-day activities of your salespeople, then it will be ignored and eventually abandoned. If it’s too little process, then its overall impact will be limited. Therefore, it’s wise to ascertain the minimum level of rigor required to enable better measurement and management of the role.

The second condition is that the process must be surrounded by the other components of a holistic change management system if the impact of a new sales process is to be sustained. Notably, the process needs to be supported by the right training, tools, and metrics to integrate the new process into the daily workflow of your salespeople. Otherwise, inertia will pull the sales force’s behaviors back into a well-worn rut.

We also shared our observations regarding off-the-shelf sales processes. While they can be a perfect fit with little alteration, their prepackaged form can violate our tenets of a best-practice sales process—that is, that they are relevant, right-sized, and supported by complementary components of the overall system. Management discretion is advised when choosing whether to build or buy its formal sales processes. A single miscalculation can lead to disaster.

And finally, we highlighted the fact that not all Call, Opportunity, Account, and Territory Management processes are identical to one another. There are different varieties of each process that are intended to support different tasks. Once you identify that you need a certain process in your sales force, you must further verify that the particular process methodology aligns with your salespeople’s needs. Otherwise, your process will produce suboptimal outcomes.

With a comfortable grasp of the building blocks required at the Sales Activity level of our sales management framework, we turned our attention to identifying how you would select and align all of the vital metrics from the top to the bottom of your organization. Business Results and Sales Objectives, here we come.