CHAPTER 8

Managing with Processes and Numbers

NOW IT’S TIME TO MANAGE

So now you have formal processes in place with the appropriate tools to support them. You also have carefully selected Activities, Objectives, and Results with associated quantitative targets. You even have crafty reports that shed light on your A-O-R metrics. You’ve got what you need. Now it’s time to manage.

We previously made the claim that the job of the frontline sales manager is the most diverse of any role in a company—part marketer, part CFO, part IT director, part trainer, part coach, and parts of many other functions as well. For our purposes, though, we are concerned with how a sales manager uses metrics to manage his sales reps. Therefore, we’re going to take a slender slice of the manager’s day and illustrate it in depth. While the other slices are significant pieces of the role, we think that managers can exert the most influence over sales performance during focused interactions with their salespeople.

Recall that not all salespeople are alike. Most organizations have different selling roles that are designed to accomplish different things. Some sellers are charged with mining vast territories for leads, while others are asked to maximize the long-term value of a single account. Some make hundreds of outbound phone calls each month, while others conduct only a few face-to-face meetings a week. The nature of selling roles varies, and so do the activities that each role undertakes.

We also discussed at length how the day-to-day activities of an individual selling role determine which formal sales process they require: different activities, different process. When the right sales process is implemented, it’s congruent with the seller’s world and allows for the effective measurement and management of her activities. Therefore, within the same sales force, there might be several distinct processes at play across different selling roles.

Why do we need to revisit this point when addressing the role of a sales manager? Because there’s a subtle but very powerful implication for a sales manager who oversees different roles with different processes:

![]() You must manage different sales processes differently.

You must manage different sales processes differently. ![]()

This statement might seem obvious when you read it, but it’s a fact that is overlooked by many sales forces. Remember the conversation we shared about the enlightened sales manager whose leadership team was requesting irrelevant sales metrics on the volume of calls his account managers made? He understood that different sales roles needed different sales processes and metrics, but his peers and his sales leadership did not. They were busy trying to manage the number of calls that the company’s other account managers made. The desire is strong to manage everyone in the same way, because we tend to crave simplicity. But sales management is anything but simple.

And if a sales manager supervises several different roles, then the challenge is multiplied. The manager must measure and manage one sales process for one selling role, and another for another. And potentially another for another. It’s easy to understand why managers often fall back on a single management approach. It can get a little hectic trying to manage many processes with an appropriate level of distinction.

Accordingly, the way you would integrate a Sales Objective into an Account Management process will differ from how you’d integrate it into a Call Management process. The fundamental purpose is the same—to provide guidance and measure progress toward the Sales Objective. However, the conversations might vary greatly, one more strategic, and one more tactical. And the supporting tools would undoubtedly differ, one an account plan, and the other a call plan. There are many ways that the management of one process differs from the management of another, so let’s then examine how you would practically use A-O-R metrics to manage different types of sales processes.

MANAGING CALL MANAGERS

![]() If you manage a sales role that conducts a low to moderate number of unique, high-impact sales calls, you should probably have a Call Management process in place. Such a process will help your salespeople be more deliberate about how they prepare for and conduct high-risk conversations with prospects and customers. And it will provide a venue for managers to coach and develop the skills of their salespeople.

If you manage a sales role that conducts a low to moderate number of unique, high-impact sales calls, you should probably have a Call Management process in place. Such a process will help your salespeople be more deliberate about how they prepare for and conduct high-risk conversations with prospects and customers. And it will provide a venue for managers to coach and develop the skills of their salespeople.

When a sales manager works with a seller to plan for an upcoming sales call, the manager also has the opportunity to ensure that the salesperson’s Activities are aligned with the Objectives that are the preferred path to the company’s Results. Here is where the management rubber hits the selling road: when a salesperson is preparing to have an actual conversation with the customer and the sales manager directly influences the seller’s behavior. From the very beginning of this book, we have alluded to a manager’s ability to exert control over sales performance. Let us share an example of that actually happening.

One of our clients had a problem. The company manufactured two distinct product lines to offer its customers, one high-priced premium product and another low-priced basic product. When a sales rep encountered a prospect with sophisticated needs, the buyer would gladly pay the premium price to gain the additional functionality. And when a sales rep encountered a prospect with very basic needs, the buyer would happily accept the less functional product with a much lower price. No problems there.

The problem was that there was a third type of buyer in the marketplace. These buyers wanted midrange functionality at a midrange price, and they could neither use the more basic product nor afford the premium offering. When a sales rep encountered one of these buyers, she had no choice but to discount the price of the premium product or else lose the sale. This discounting put so much pressure on the company’s profit margins that it chose to acquire a competitor whose flagship product was perfectly suited to the mid-tier customer. It could sell this “new” product at a mid-tier price point and still defend its profit margins. Ah, sweet relief.

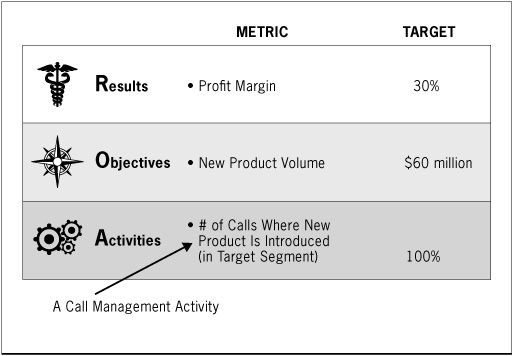

However, this new product could not sell itself. It would have to be sold through the client’s existing sales force, so behaviors in the field would have to change. Salespeople could no longer take the easy way out by discounting the high-end product—they would have to learn to sell the midrange offering, which required a push (and an occasional shove) by their sales managers. So to achieve their Result of maintaining a 30% Gross Profit Margin, the company’s leadership set an Objective to sell $60 million of the new product in the following year. And to accomplish that, they planned to propose the midrange product in 100% of their sales calls on mid-tier prospects.1 Consequently, they decided to drive all of this change through their existing Call Management process. See Figure 8.1.

FIGURE 8.1 A-O-R Metrics: Call Management Example

We happened to be working with this company at the time, coaching its sales managers. Therefore, we were able to observe many interactions between the managers and their reps, some of which were good, and some of which were bad. The best ones tended to follow a storyline something like this:

Sales Manager: So, Phil, what calls do you have coming up this week?

Phil: Well, I have several pretty standard meetings with my existing customers, but there’s one prospecting call that’ll be particularly interesting. It’s probably worth chatting about, in fact.

Manager: What kind of company is it?

Phil: It’s a pretty new player in the market, so I don’t think you’d know it. But its operation is pretty similar to Ye Old Company, which I think you do know pretty well.

Manager: Sure, Ye Old was a customer of mine way back when I was in your shoes. So what are your objectives for the call?

Phil: Well, I’ve met with its people once before, and they agreed to let me come back to give them a product demonstration. My objectives are, one, to impress them with the demo and, two, to get them to order a small number of units. Once they see how superior our product is, they’ll be begging us for more.

Manager: Sounds reasonable. So which product are you going to demo for them?

Phil: The old standby—our super-expensive, super-functional product line.

Manager: Hmm. I seem to recall that Ye Old Company didn’t have needs quite that sophisticated. You said they were similar to Ye Old, didn’t you?

Phil: Yes. You know how it will go. They’ll love the product but not the price, so they’ll end up negotiating a pretty good deal for themselves. It’s a win-win.

Manager: Well hold on. We have the new not-so-expensive, not-so-functional product that would probably be perfect for them. Did you consider that?

Phil: Sure. But giving them the high-end product at a midrange price is a slam dunk. I’ll have them closed by the end of the month.

Manager: It may be a slam dunk, but recall our commitments for the year. We’ve got to sell $60 million in the new product line, and we promised to propose the product to 100% of our mid-sized prospects. How are we going to meet those numbers and get our rewards if we start to veer off course?

Phil: Yeah, I get your point. The not-so-expensive product line is probably the best fit, though not the easiest sell.

Manager: Then let’s spend some time planning how you’re going to turn this product into a slam dunk during the call.

Phil: Sure thing. Let’s do it.

Conversations like this illustrate how a Call Management process can lead to altered behaviors in the field. They also reveal how powerful metrics are in focusing a sales force. In the absence of a formal Call Management process, this seller would have continued down the path of least resistance and discounted the high-end product. And without A-O-R metrics as guideposts, the manager’s argument would not have been so convincing. Processes and metrics are a powerful combination.

Note that Call Management activities are a very tactical affair. Ideally, this manager and rep would go on to plan specific questions to ask, objections to anticipate, and other very detailed actions. If you manage call managers, then you’ll appreciate the granularity of this conversation. You have to be prepared and willing to dive into the particulars of a salesperson’s sales call and align his behaviors with the outcomes you both want. In a sales force, there are strategies, and then there are tactics. Call Management is all about aligning the two from a tactical perspective. Let’s now examine an Opportunity Management process to see how it differs.

MANAGING OPPORTUNITY MANAGERS

![]() If you manage a sales role that has to navigate complex, multistage sales cycles, then you should probably have an Opportunity Management process in effect. Such a process will help your salespeople examine the competitive landscape, qualify the opportunity, form a strategic approach, engage the necessary resources, and manage a project plan to win the deal. For salespeople who pursue fewer, larger deals, Opportunity Management is often a must-have sales process.

If you manage a sales role that has to navigate complex, multistage sales cycles, then you should probably have an Opportunity Management process in effect. Such a process will help your salespeople examine the competitive landscape, qualify the opportunity, form a strategic approach, engage the necessary resources, and manage a project plan to win the deal. For salespeople who pursue fewer, larger deals, Opportunity Management is often a must-have sales process.

As with Call Management, Opportunity Management activities are an ideal venue for a sales manager to ensure that her seller’s Activities are pointed toward her stated Objectives. In addition to improving the seller’s chances of winning the opportunities (an Objective of Sales Force Capability), the early stages of a pursuit can also be very powerful in guiding salespeople to the right types of deals (Customer Focus and Product Focus). As we all know, chasing the wrong deals can consume an enormous amount of time and yield frustratingly little return. To illustrate how Opportunity Management can help avoid such wasted effort, let us share an example from a past client.

This particular client didn’t necessarily have a problem—it simply wanted to grow its revenues. While working with the client to elevate its sales managers’ ability to coach their reps, we made some very interesting observations. First, its sales reps were winning on average about 36% of the deals that they put into their pipelines, which is not too bad considering the number of formidable competitors in their marketplace. But one sales manager’s team was winning 70%, twice the Close Rate of the rest of the sales force. Even more fascinating, we noted that the average size of his team’s pipeline was 25% smaller than that of its peers. Finally, his team conducted nearly 50% more prospecting sales calls than the rest of the sales force, and it accordingly produced almost 50% more in revenue. More sales calls, higher Close Rates, more revenue, yet a smaller pipeline. We had to investigate.

We followed this sales manager around for a day in an attempt to isolate the source of his magical pipeline management abilities, and it didn’t take long to find the secret sauce. After watching the manager meet with several of his reps to review the opportunities in their pipeline, a pattern of behavior became apparent. The conversations during these meetings were all some version of this:

Superstar Sales Manager: So, Rachel, tell me what you uncovered this week.

Rachel: This week I found three new opportunities that I think are pretty good. Let me walk you through them.

Manager: Great.

Rachel: The first is with a company we’ve done business with in the past. We know the key buyers really well, and their current need is right in our product sweet spot. I looked into it, and the company has a solid credit rating and is looking to make this purchase before the end of the quarter. All the stars seem to be aligned on this one.

Manager: So you think this is a pretty qualified opportunity then?

Rachel: I can’t imagine any deal being more qualified than this.

Manager: OK, then you should probably go ahead and put it into your pipeline.

Rachel: Great. So the next opportunity is a little less defined. We’ve done business with this company too, but our primary contact there has since left the company. It’s definitely in the market to buy, and our products are probably the best suited for it. I just have to vet it a little more. I have a meeting at the company next week to meet the new folks.

Manager: OK. Then let’s leave that one out of the pipeline until we have more information. Let’s revisit it after your meeting.

Rachel: Sure. This final lead is also with a company we’ve done business with, Stay Aweigh, Inc.

Manager: Argh. I remember Stay Aweigh. We did something small with it last year. It was a nightmare.

Rachel: Yes, I heard about that from someone else. It sounds like it was difficult to deal with.

Manager: Oh, it was terrible. Stay Aweigh brought in eight bidders and pitted us against each other for this small piece of business. Then it made us go through two rounds of presentations to reduce it to five and then three competitors. We had to give its buyers sealed bids and everything. We eventually won the deal, but I’d never want to go through that again.

Rachel: Wow. I don’t think I want to go through that either.

Manager: Well, I’m not telling you not to pursue the opportunity, but you’d better see how big the deal is and how many competitors it has at the table. Regardless, please don’t put it into the pipeline until you’ve qualified it a little better.

Rachel: No problem. I’ll just put the first lead into the system and then wait until I have more info on the other two.

Manager: Good job. Let me know what you find out.

From this dialogue, you can easily see the source of his pipeline management wizardry. Unlike the other managers who were only discussing deals with their reps when they were late in the sales cycle and near closing, he was helping his reps qualify (and more often than not, disqualify) new leads at the front end of the sales cycle before they went into the CRM tool. By doing so, he was keeping bad deals out of the pipeline entirely, which is why his team’s Close Rate was so high. And since his sellers weren’t wasting their time taking bad deals too far into the sales cycle, they had time to make more prospecting calls and find more good opportunities to pursue. A simple but significant lesson in pipeline management is to keep out the junk.

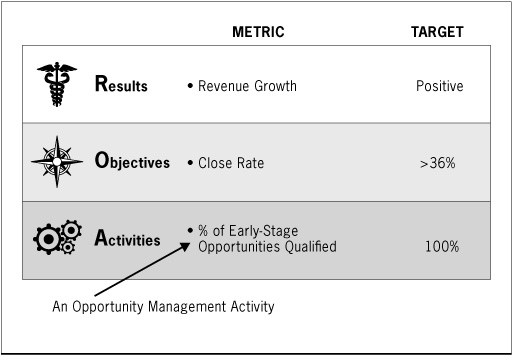

With this best practice revealed, the company set into motion some A-O-R–type changes. To achieve positive Revenue Growth, it chose to improve a measure of Sales Force Capability, its 36% Close Rate. It did so by formalizing a new “prospecting meeting” during which each manager would help his reps meticulously qualify all new opportunities before they got into the pipeline. This new Activity of qualifying early-stage deals was welcomed by all, and the additional revenue soon followed (see Figure 8.2).

FIGURE 8.2 A-O-R Metrics: Opportunity Management Example

This example illustrates not only the power of good Opportunity Management, but it also highlights the difference between managing call managers and managing opportunity managers. Call Management is extremely tactical, while Opportunity Management is more strategic. It’s possible for the same manager to do both. In fact, both are required to practice effective pipeline management. However, managers have to toggle their mind-set from strategy to tactics, which is sometimes more difficult than you might expect. Two different processes, two different management tasks.

MANAGING ACCOUNT MANAGERS

![]() Account Management takes the discussion to an even higher level of thinking. Of course, this is only a relevant process if your salespeople are tasked with maximizing the long-term value of important customers. Recall that Account Management activities help salespeople to align their business needs with those of the customer and to engage in the critical activities that will build mutual value between the organizations. If a handful of accounts represent a large portion of your business, then you can’t afford to leave anything to chance. Where major customers are concerned, surprises are a very dangerous thing.

Account Management takes the discussion to an even higher level of thinking. Of course, this is only a relevant process if your salespeople are tasked with maximizing the long-term value of important customers. Recall that Account Management activities help salespeople to align their business needs with those of the customer and to engage in the critical activities that will build mutual value between the organizations. If a handful of accounts represent a large portion of your business, then you can’t afford to leave anything to chance. Where major customers are concerned, surprises are a very dangerous thing.

Sales managers will then want to be involved in their sales-people’s Account Management activities for at least two reasons. First, managers need to make certain their account managers are truly aligning their own needs with those of their customer. It’s all too easy for a seller to obsess over what he wants from the relationship and to unintentionally ignore the customer’s business objectives. In a long-term business relationship, keeping the two companies’ agendas in strategic harmony is a mission-critical task.

At the same time, your company still has its own Objectives and Results to achieve. A manager should therefore tune in regularly to ensure that the salesperson is not only aligned with the customer’s needs but also that his Activities are driving toward your own company’s goals. It’s a wonderful strategy to put your customers’ interests first, but you’d better have your own in a close-second position.

One of our clients demonstrated an excellent example of good Account Management that’s worth sharing. The company’s primary business was to provide industrial customers with leasing agreements for heavy equipment like tractors and bulldozers. The company would purchase the equipment directly from the manufacturer and then lease it to its customers for a specified term, typically two to five years. When the lease would expire, the company’s sales force would attempt to renew the contract based on the depreciated value of the equipment. A pretty good business, when the price of the equipment and your own financing are in line.

But the company came under pressure to increase its profit margins, so it conducted an in-depth analysis to identify new sources of profitability. It discovered that given current market conditions, it would actually be more profitable if the salespeople could convince their customers to purchase the equipment from them when the lease term expired rather than renewing the lease for an additional two to five years. This was a pretty interesting finding that could make a large near-term impact, since the equipment leases are constantly expiring. Now the client just needed to change the sales force’s behaviors to take advantage of the new strategy.

Since the company maintained relationships with very large customers, they already had a very structured Account Management process in place. The sales managers therefore scheduled meetings with their reps to launch this new initiative. The conversations went something like this:

Sales Manager: So, Anna, you’ve probably heard about our new strategy for equipment that is coming off-lease.

Anna: Yes, I understand that certain types of equipment we’re going to want to sell to the customers rather than trying to renew their leases.

Manager: That’s right. So what we need to do is take a look at all of your accounts to identify which customers have equipment that would qualify for sale and when their leases are due to expire.

Anna: Well, let’s start with BuildCo. It has about 50 machines under lease, but it looks like only 20 of them are the types of equipment that we’d now want to sell rather than lease. And only 10 of those are coming due within the next six months. The other 10 leases don’t expire for another three years. I guess this will be the same for all my accounts. There’ll be a subset of their equipment that we’ll want to try to sell, and those leases will be expiring at staggered intervals. So I won’t be able to just go out and do this all at once. I’ll have to plan my approach carefully over time.

Manager: Yes, that’ll be the case for everyone. It’s gonna take some detailed planning so that nothing falls through the cracks.

Anna: I tell you what. Let me go through all of my accounts and identify the equipment that we can target to sell in the next 12 months. Then we can review that list together and update whichever account plans need amending.

Manager: Good idea. And so you know, we’d like to try and sell 25% of all eligible equipment as it comes off-lease. To do so, I’d suggest that you schedule meetings with your eligible accounts 120 days before their leases are to come due. That should give you enough time to sell them on the idea and execute all the paperwork.

Anna: Sounds good. Can we reconvene next week to go through the plans for each account?

Manager: Yep. Talk to you then.

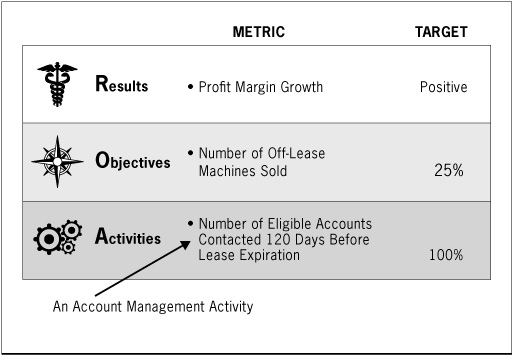

Again, this company was able to quickly shift its strategic direction because it had formal processes in place that enabled proactive management of its sales force (see Figure 8.3). When leadership chose to increase its company’s Profits by shifting its Product Focus—basically, selling machines rather than selling leases—it leaned on its Account Management process to create the desired outcomes. If the sales force contacted all of its eligible customers 120 days before their leases expired, it felt that it could predictably sell a certain number of machines, which would in turn boost profitability. And it did. Good management led to good Results.

FIGURE 8.3 A-O-R Metrics: Account Management Example

Note that this interaction between the sales manager and the rep was even further removed from Call Management than the Opportunity Management discussion. This was a conversation at a very strategic level that would help the sales force uncover new opportunities that would ultimately require call planning, but Account Management activities look further into the future. They are a kind of “meta” discussion that typically takes place with less frequency than Opportunity and Call Management activities. Yet again, we see a different management cadence for a different management task. And yet again, the manager was able to directly influence sales rep behaviors by using specific metrics.

MANAGING TERRITORY MANAGERS

![]() If you manage a sales role that has to allocate its time among different types of prospects or customers, then you should probably have a Territory Management process in place. Such a process will help your salespeople prioritize their targets, design their call patterns, and execute their sales calls in the most efficient fashion. In the world of time-constrained selling, Territory Management can make certain that your sales force’s effort is being used in the most highly leveraged way.

If you manage a sales role that has to allocate its time among different types of prospects or customers, then you should probably have a Territory Management process in place. Such a process will help your salespeople prioritize their targets, design their call patterns, and execute their sales calls in the most efficient fashion. In the world of time-constrained selling, Territory Management can make certain that your sales force’s effort is being used in the most highly leveraged way.

We noted before that much of the upfront analysis in a Territory Management process is often performed by resources other than the frontline salesperson—sales managers, sales operations, marketers, or others. But at some point in the process, it becomes the salesperson’s job to arrange her travel or call schedule and hit the ground selling. This is when the sales manager should engage to keep the salesperson on the right patch of ground. There are many forces that can drag a salesperson off the recommended path—fire-fighting, friendships, comfort, or convenience—so the manager needs to help guide the sellers to the right doors.

We have a client that was once a classic Account Management shop. It had historically received more than 80% of its revenue from long-term client relationships, and the other 20% just fell into its waiting arms because of the brand’s strength in the marketplace. It had world-class account managers, with all of the processes, tools, metrics, and training in place to predictably retain and grow its customer relationships. Then came a recession.

Suddenly, its major customers were going out of business daily, and its customers that remained were shrinking, not growing. Things were bad and getting worse. Plan A was no longer a sustainable go-to-market strategy. The company needed a good plan B before its doors were the ones with locks on them. There was only one thing to do: get more customers.

However, prospecting was not this sales force’s thing. Its salespeople were accustomed to visiting their existing customers at regular intervals, and their prospecting skills were rusty—if they ever shined at all. As we now know, when changes in behavior are needed, sales processes are your friend. So this company’s management team made a new friend, the Territory Management process.

They implemented a properly rigorous series of activities to identify and prioritize prospective customers, and the leads were distributed to the sales force in a highly systemic manner. They even created Activity-level metrics to watch the prospecting surge from the war room, including a measure that tracked the number of prospecting calls each salesperson made. Everything was in place for a world-class prospecting effort, except that their salespeople didn’t want to prospect.

Not only was it an unfamiliar activity for the account managers, it wasn’t particularly fun. The management team realized that their salespeople weren’t exactly suited to the task, but they couldn’t replace their entire sales force with master prospectors, nor did they want to. They expected that the economy would eventually return with their Account Management process in tow, so they decided to utilize the key lever for sales force change—the frontline managers. Thus began a series of weekly conversations between the salespeople and their managers that went like this.

Sales Manager: So Nick, what do you have on the docket this week?

Nick: (Handing the manager a new spreadsheet with his intended customer visits for the week) Well, I’m headed downtown this afternoon and tomorrow, and then north of the city on Tuesday. I’ll hit the other suburbs on Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday. It’s a routine that I like to try to follow during the first week of each month.

Manager: Hmm. The names on this sheet look pretty familiar.

Nick: Well, they are. They’re my most important customers. I want to see all of them at least once every 30 days, so I usually just go ahead and knock it out at the first of the month.

Manager: Well, I’m a little concerned that your Number of Prospecting Calls won’t come in where it needs to be at the end of the month. With this new customer acquisition strategy, we really need to pour on the prospecting. Do you think you might need to consider changing your call pattern?

Nick: Well, I can’t ignore my best customers. Probably 75% of my incentive compensation is on that sheet of paper.

Manager: I’m not proposing that you ignore your customers, but we have some pretty specific targets for prospecting calls, as you know—16 each month per rep. And it’s a pretty visible number right now. Don’t you think you should sprinkle in some prospecting calls this week? Particularly downtown, where the density of targets is so high?

Nick: Well, I could, but who would you have me take off that list in your hand?

Manager: Well, the question is who would you take off the list to free up some time for an additional day prospecting downtown?

Nick: If I had to, I’d take off the smaller customers in the suburbs, but I’ll be driving right by them. For instance, when I visit Mega Company on Wednesday, Mini Co. and Micro Inc. are practically across the street. Even though they’re not buying a lot from us now, they’ve been our customers for decades. I think they deserve a 10-minute call.

Manager: I can’t dispute that, but it’s an issue of priority. Our priorities have shifted this year, for obvious reasons, and you’d agree that new customers are the only way we’re going to hit our quotas for the foreseeable future.

Nick: Yes, I do agree with that. I just feel like I need to get these current customers out of the way before I start making calls on people I don’t even know.

Manager: OK. Then just help me understand how you’re going to make your target of 16 prospecting calls this month if you make no prospecting calls this week.

Nick: I’ll just have to hunker down and prospect hard for the rest of the month.

Manager: That would probably work if you had no unexpected drags on your time, like a shipment coming up short or some other fire to fight.

Nick: Well, that’s not gonna happen. Something always comes up. (Pause) OK. You’re probably right. I’ll skip the smaller customers this week and try to spend some more time prospecting downtown. If I get all my 16 calls done early, then I’ll visit the smaller customers at the end of the month.

Manager: Sounds like a good plan. Then let’s talk about who should be your top prospects downtown.

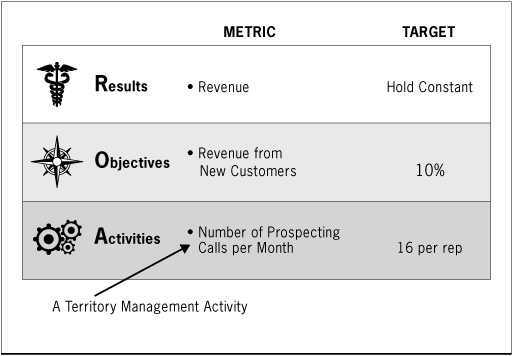

In this example, the company was trying to defend its Revenue by acquiring new customers. It was an unnatural act for its account managers to suddenly engage in prospecting Activities, but it’s what was required to achieve the desired Objective and Result. See Figure 8.4. A Territory Management process became the vehicle for changing sales force behaviors in the field. And again, having quantified A-O-R targets gave managers a mechanism to focus their sellers. In the absence of this process and metrics, the sales force would have stayed on its comfortable course, and the Revenue would have never come. With them, management was able to exert a level of control over their sales performance during a time that it was desperately needed.

FIGURE 8.4 A-O-R Metrics: Territory Management Example

AND SALES FORCE ENABLEMENT

![]() Though sales managers don’t “manage” Sales Force Enablement in the same way they manage salespeople in the other sales processes, Enablement activities like training provide support to the sales force that greatly influences certain Objectives and Results. Sales Force Enablement activities should therefore be proactively measured and managed in the same fashion as the other sales processes that are more seller-centric.

Though sales managers don’t “manage” Sales Force Enablement in the same way they manage salespeople in the other sales processes, Enablement activities like training provide support to the sales force that greatly influences certain Objectives and Results. Sales Force Enablement activities should therefore be proactively measured and managed in the same fashion as the other sales processes that are more seller-centric.

In our example of Opportunity Management earlier in this chapter, we discussed a company that implemented a new “prospecting meeting” as a mechanism to better qualify deals early in the sales cycle. A savvy reader might have detected not only the new Opportunity Management activity of early stage qualification but also a new Sales Force Enablement activity: an additional coaching interaction between the sellers and their managers. This drove toward the stated Objective of increasing sales rep Close Rates on the way to increased Revenue.

This company’s sales leadership of course wanted numbers on its war room wall to ensure that the opportunity-coaching Activities were taking place as planned. And the plan in this case was for every manager to conduct a prospecting meeting with each of his sales reps at least every two weeks. The company then encountered the classic management challenge, collecting dependable Activity-level data on those meetings.

After batting around several manual and automated ways to collect information on the new coaching interaction, company executives eventually decided to deploy a periodic survey to the sales reps. Surveying the sellers would not only allow management to ask whether the meetings were taking place, it would also allow them to inquire about the quality of the coaching they were receiving. They didn’t just want their managers coaching their sales reps. They wanted to know that it was valuable to the rep.

And thus, a new Sales Force Enablement metrics was created, though it wouldn’t come from their traditional reporting system. Someone would have to “write” it on the wall, but it would be there nonetheless. This demonstrates how powerful metrics can be in not only changing sales reps’ behavior but also sales management’s.

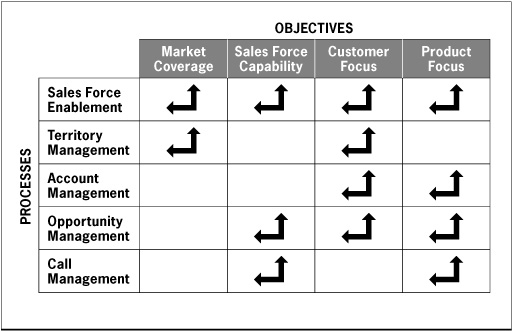

WHICH PROCESS FOR WHICH OBJECTIVE?

There is one final point that we need to make regarding the use of Sales Processes to influence Sales Objectives. You might have sensed as you walked through the previous examples that some Processes are more suited to accomplish certain Objectives than others. For instance, Call Management is a process perfectly suited to improve your Sales Force Capability, since it will tend to increase Conversion Rates and other metrics that are affected by better selling. However, engaging in Call Management activities—such as planning, conducting, and debriefing sales calls—will not increase your Market Coverage. Call Management is about improving the quality of customer interactions, not the quantity.

We sensed these relationships, too, as we originally attempted to define the linkages between the three levels of sales metrics. In the same way that we put “The Question” to each of the metrics at the beginning of our research project, we posed a different question to each of these five processes:

![]() Can this process directly affect each Sales Objective?

Can this process directly affect each Sales Objective? ![]()

And so it went:

Call Management process. Can you directly affect the Objective of increased Sales Force Capability? Of course you can. Better Call Management will help move to more deals through the sales pipeline.

Opportunity Management process. Can you directly affect the Objective of increased Sales Force Capability? Yes, you can too. This process will unquestionably help salespeople win more deals, since it often helps them successfully shepherd opportunities through the sales cycle.

Unlike our extended labor with the individual sales metrics, there were thankfully much fewer than 306 questions to ask this time around. However, the questions were equally as difficult to answer in some cases. For instance:

Territory Management process. Can you directly affect the Objective of increased Sales Force Capability? Well, sure. If you reallocate your sales force’s prospecting calls toward more qualified prospects, then sales reps should win more deals. It would seem that smarter Territory Management will drive Sales Force Capability metrics like Conversion Rate. So Territory Management must affect Sales Force Capability. But wait. Steering the sales force toward more receptive prospects is actually affecting the Sales Objective of Customer Focus, not Sales Force Capability. Territory Management won’t make the sellers any more capable; it will just put them in front of more susceptible prospects. So Territory Management might indirectly affect Conversion Rates, but only by shifting Customer Focus. Tricky, tricky.

This is a very important insight as it pertains to influencing sales performance by managing sales processes:

![]() To achieve certain Sales Objectives, you have to manage certain sales processes.

To achieve certain Sales Objectives, you have to manage certain sales processes. ![]()

Let’s take each Sales Objective in turn and see which processes can be managed in order to influence each of them directly.

Market Coverage

These metrics are intended to show how much selling effort is available to deploy against your targeted customers. Measures of Market Coverage, such as Number of Total Selling Hours or Percentage of Customers Contacted, reveal whether your sales force is capable of covering its territories with a sufficient level of intensity. Clearly those can be directly affected by managing Territory Management activities like adjusting the frequency of your sales reps’ calls. Your capacity to cover the market can also be influenced through Sales Force Enablement activities like recruiting and hiring. So both Territory Management and Sales Force Enablement processes are two good candidates to affect Market Coverage.

However, proactively managing your Calls, Opportunities, or Accounts will not increase your Market Coverage. It will make the selling effort more effective once you’re engaged with a prospect, but it won’t enable your sales force to call on any more customers. Those three processes are therefore poor candidates for affecting your Market Coverage.

Sales Force Capability

These metrics, on the other hand, are all about the effectiveness of a sales force in getting deals to closure. With this Sales Objective, processes like Call and Opportunity Management will unquestionably help you to move more deals through the pipeline and improve metrics like Close Rates. And Sales Force Enablement activities, such as training and coaching, will also surely boost your salespeople’s capability. So Sales Force Capability can be predictably improved by managing your calls and opportunities and by engaging in enablement activities.

Account Management, though, will not necessarily help you advance and close more individual deals. It may help you uncover more opportunities in your existing accounts, but it won’t increase your chances of winning them once you’re engaged. Account Management is focused on the big picture, realizing the greatest value from long-term customer relationships. Territory Management, on the other hand, is about winnowing an overwhelming number of prospects into a manageable group of targets. It helps salespeople focus on those customers that might provide the good deals. Account and Territory Management processes will both help you identify new opportunities, but they won’t increase the likelihood of your winning a specific deal. Not a good lever for Sales Force Capability metrics.

Customer Focus

Metrics of Customer Focus shine a light on your sales force’s ability to acquire, retain, and grow your ideal customers. As you might expect, Territory Management can be quite useful in this regard, allowing you to direct your salespeople toward the types of prospects you want to acquire. And when it comes to retaining and growing existing customers, Account Management is probably the most powerful process of all. Opportunity Management is even an excellent means to focus your sales force on certain types of customers, because you can use it to qualify (and disqualify) new prospects entering the pipeline. Of course, Sales Force Enablement will help you with this Objective by allowing you to train and equip your salespeople to do all of the above.

The only process that can’t help you improve your Customer Focus is Call Management. This is because you never need to engage in Call Management activities until after you’ve made the decision to call on that particular customer. Trying to plan a call in order to focus on a certain type customer would be like trying to plan a trip in order to select a destination. The execution would come before the strategy. Once you select a customer to target, Call Management would be an extremely useful process. But beforehand, it’s completely useless.2

Product Focus

This final Sales Objective uses metrics to reveal whether the sales force is selling your preferred types of products. As we saw in a previous example, good Call Management can nudge a salesperson to promote a particular product during an upcoming sales call. Opportunity Management can accomplish the very same thing, but during the course of a multistage sales cycle. Account Management activities can also drive sales of preferred products by helping reps form strategies to insert them into existing accounts. And to promote a new product, you might need to conduct product training, which is a mainstay Sales Force Enablement activity.

The only process that is ineffective in focusing your sales force on a specified product is Territory Management. But wait. If you launch a new product that’s designed for a unique type of customer, wouldn’t redeploying the sales force toward that customer base help you sell the new product? Yes it would. But again, that is directly influencing your Customer Focus, not your Product Focus. The two may go hand-in-hand, but simply managing your territory differently will not inherently lead to different product sales. Tricky, tricky. So to accomplish specific Sales Objectives, you should manage certain sales processes. Figure 8.5 summarizes the relationships between the two.

FIGURE 8.5 Certain Sales Processes Drive Specific Objectives

Note that Sale Force Enablement will always be there for you, regardless of which Sales Objective you choose to emphasize. Training, coaching, and equipping your salespeople for success are universally valuable activities. You do need to be purposeful, though, to ensure that your enablement activities are in direct support of your current Sales Objectives. For example, training your salespeople to conduct better sales calls might not be the smartest choice if your primary Objective for the year is to target different customers. You might make a bigger impact by training them to manage their territories. So while Sales Force Enablement might always be a good idea, you need to make certain that you’ve selected the most high-leverage enablement activities for the particular point in time.

Beyond Sales Force Enablement as a universal lever of sales performance, you need to become a little selective about which processes you choose to manage. For instance, if you want to increase your Market Coverage, then you might also want to lean on your Territory Management process. Or if you want to improve your Sales Force Capability, then you could do so through your Call and Opportunity Management activities. Should you decide to suddenly shift your Customer Focus, then Opportunity, Account, and Territory Management processes would each be potential levers for you to pull. And if your Product Focus needs to change, you could steer your sales force accordingly though your Call, Opportunity, or Account Management activities.

This chart shown in Figure 8.5 is a handy little tool that illustrates the relationships between certain Sales Processes and certain Sales Objectives. After identifying the Objective across the top that you want to influence, you can select a process along the left-hand side that’s a viable option for managing that change. It’s about as color-by-numbers as sales management gets. It might not be easy to achieve your Objective. As we’ve discussed, change management is hard. But it’s no longer a mystery of what you need to do. We’ll take a challenge over a mystery every time.

THE TREASURE MAP

We only half-jokingly refer to this Process-Objective matrix as a treasure map for sales management. If the treasure you’re seeking is to sell a new product line, then this map will tell you how to find it. And if next year’s treasure is to increase your win rate on deals, then this map can point you there, too. No matter what your Sales Objective becomes, there’s a direct path to get there from here. You just need to be clear about your destination, and this chart will illuminate the way.

But instead of a treasure map, many executives who see this chart view it as a trail of broken dreams. They look at it and reflect on all of the Sales Objectives they never fully achieved because they weren’t pulling on the right levers in their sales force. They’d wanted deeper customer penetration, but their sales force didn’t have an Account Management process. Or they’d wanted to get more deals through their pipeline, but they didn’t have an Opportunity Management process. They had identified their desired Business Results and even isolated some Sales Objectives. They just didn’t take it down to the field level, making them war room generals with no control over the battle.

If you couldn’t before, you should now be able to appreciate how these five sales processes are the levers and pulleys to control sales force performance. Depending on which Objective you want to accomplish, there are a few places on this treasure map where you know you can apply focused effort to directly influence the outcome. Want greater Market Coverage? You know you have two ways to accomplish it. Want increased Sales Force Capability? You know you have three. More Customer Focus or Product Focus? You have the privilege of four. If there’s a will, there are several specific ways.

So this treasure map is the final piece of the sales management code you need to gain control of your sales force’s performance. If you want to proactively Manage Your Sales Force toward your ultimate goals, then you have a reasonably straightforward series of tasks to execute:

1. Carefully define the Business Results you want.

2. Identify (through thoughtful analysis) the Sales Objectives that will most easily lead you to those Results.

3. Select a process or processes that can directly influence your Objectives.

4. Choose specific Activities within those processes that you can manage on a day-to-day basis.

5. Make certain that you have quantified targets for all of your chosen Results, Objectives, and Activities.

6. Manage.

Whether you are a chief sales officer or a frontline sales manager, this path to greater control is the same. As a practical reality, you may have to share responsibility for some of these tasks with others across your organization—senior executives, marketers, and others frequently contribute to the selection of an organization’s specific Results, Objectives, and Activities. But regardless of who owns the individual tasks, the overall plan is the same. Plan from the top to the bottom, and then manage from the bottom to the top. Finally, this is how you “work” the numbers on your own war room wall.

AN ADVANCED DEGREE: SELECTING A-O-Rs FOR THE INDIVIDUAL SELLER

We will close this chapter with a word about choosing Activity, Objective, and Result metrics for an individual salesperson. A single set of A-O-R metrics can certainly be deployed to an entire sales force, and that is how we’ve treated them in this book. In a sales force with many people in the same selling role, this is a perfect way to measure and manage their effort. If you want all of your salespeople doing similar things to achieve the same outcomes, there is no better way to set expectations and report progress than to provide a common set of performance metrics.

However, many organizations don’t have the luxury of a sales force in which all of their salespeople perform identical tasks. Even within the same role, different salespeople may operate in very different day-to-day environments. In these cases, applying a single set of A-O-R metrics across the sales force may be problematic or even counterproductive. Consequently, A-O-R metrics must often be formulated at the individual level. Let us give you an example from recent a conversation with a client.

We were meeting with the head of sales for a global manufacturer to discuss the sales manager coaching program we were developing for his team. He manages a relatively sophisticated organization that sets clear expectations for its salespeople at both the Result and Objective levels. Its desired Business Result is always the same—Revenue Growth—but it tracks lots of Sales Objectives. Among the most prominent are Customer Focus numbers like New Customer Acquisition, Customer Retention, and Share of Wallet, because their customers are fickle and tend to change suppliers. Given the variety of Sales Objectives he had on his war room wall, we were questioning the head of sales about his priorities to determine which Sales Activities our coaching program should emphasize. His response was not uncommon, but it carried with it some substantial implications for his sales managers. He told us this:

Look, the top priority is to make our Revenue goal. That’s how we’re all ultimately measured, and that’s what the CEO expects me to produce. Now, do I really care if those sales come from a new prospect or an existing customer? Sure, we have targets for that, but the reality is that those particular numbers will vary by territory. Some reps have newer territories with lots of untapped prospects, while others have more mature territories where we’re already highly penetrated. It’ll have to be up to their sales managers to determine the best strategy for each rep. In order to make their quotas, some will need to target new prospects, and others will need to work on their current customer base. Regardless, they have to find a way to hit their quotas. That’s the number that matters to me.

This sales leader’s comments will ring true to many reading the passage. The ultimate goal is always the Business Result, in this case, Revenue Growth. The Sales Objectives, however, are less strictly enforced, as long as the revenue number materializes throughout the year. But the reason that the Customer Focus Objectives are less important to this sales leader is not because he’s indifferent. In fact, he later shared with us a rather strong desire to acquire new customers. The reason the Customer Focus numbers are more fluid for him is that the most realistic path to Revenue Growth varies by rep. The differing customer demographics within each territory demand it. Some reps will succeed by acquiring new customers, while others will need to mine their existing accounts. He therefore leaves it to his managers in the field to identify the best Customer Focus Objectives for their reps.

There’s no inherent problem with delegating this strategic decision to the frontline managers, but there are some inherent challenges. The first challenge is that each sales manager must do the analysis to decide which Objective makes the most sense for each of his sales reps, to acquire new customers or to increase penetration within their existing accounts. In reality, most of the reps will probably end up choosing to do a little of both, which could potentially lead to a loss of focus. But let’s assume for a moment that their sales managers are thoughtful and able to help their salespeople select good, crisp Customer Focus Objectives.

The second challenge is that the managers will need to set quantitative targets for each sales rep’s chosen Objective. Again, we’ll assume that the sales managers are skilled enough to select proper targets for New Customer Acquisition and increased Share of Wallet, but the managers now have the tedious duty of tracking Customer Focus metrics that vary from rep to rep. This is not an insurmountable task. It simply means that the managers and reps must be diligent about documenting all of their decisions and tracking performance. The real challenges, though, come at the Sales Activity level.

Each sales manager will likely have reps pursuing different Sales Objectives, which means that the reps should probably be managed using different sales processes. For those reps who are pursuing a new customer acquisition strategy, a Territory Management process would be quite useful in helping them target the most high-potential prospects. Allocating their time efficiently across their territories will be critical to success.

On the other hand, those reps who are executing an account penetration strategy should almost certainly employ an Account Management process. This will help them formulate strategies to increase their Share of Wallet with each of their selected accounts. And of course, the manager will need to set specific metrics at the Activity level for both groups of reps.

Allowing the managers and reps to choose their own Sales Objectives has complicated the manager’s world substantially. If the company had been able to communicate a single set of A-O-Rs across the sales force, the managers could have focused their effort more easily on making sure that those metrics were met by their reps. However, that wasn’t practical, given the variable composition of the salespeople’s territories. The responsibility for selecting the right Objectives and Activities to accomplish the stated Result fell to the frontline sales managers.

You’ll probably recognize that this is not an unusual scenario. Executives frequently set company-wide financial targets and then leave it to the field to identify the best Objectives and Activities to get there. Doing so can lead to a menagerie of go-to-market strategies that causes the lack of focus that this book is intended to eradicate. However, it’s not necessarily undesirable to have managers in charge of their own A-O-R metrics.

Allowing A-O-R metrics to be developed in the field can actually be a smart management strategy. In companies like the one we just described, giving this responsibility to the managers will ensure that each sales rep has a set of metrics that’s both relevant and achievable. Metrics that are irrelevant and unachievable are highly de-motivating, so there’s a strong appeal to selecting the metrics as close to the ground as possible. But there is one large caveat to this strategy:

![]() The sales managers must be highly skilled with the A-O-R framework.

The sales managers must be highly skilled with the A-O-R framework. ![]()

When sales managers are skilled in the theory and practice of A-O-Rs, they are able to set distinct sets of metrics at the individual level that remain in alignment with your higher-order organizational goals. What’s wanted at the top of the organization is adeptly driven from the bottom. But when managers are not as skilled in using metrics to manage, the sales force can veer off course by design and abandon its strategic focus, which is not what you want to see if you’re the one standing in the war room.

But sacrificing uniformity across the sales force for the sake of local management is often a good trade. In companies that have a clear understanding of the organization’s overall goals and whose sales managers know how to use metrics to manage their reps’ Activities toward those goals, managers become an even more powerful lever for improved sales performance. They have the ability to guide their salespeople purposefully and then course-correct when the market signals trouble. There’s little (if anything) in a sales force that is more magnificent than a talented sales manager, unless it’s an entire team of them.

So whether you select a single set of A-O-R metrics for your whole sales force or you empower your managers to steer for themselves, developing the skills and knowledge to keep your organization in alignment is key. We’ve all known sales forces that lacked management rigor, and the battlefield is not a safe place for them to be. A sales force that has a good battle plan and knows how to execute will be victorious every time, and a tight framework of metrics that drives the right behaviors is the best battle plan we know. Teach your sales force to manage with metrics, and the world will be yours for the taking.

STATUS CHECK

As we neared the end of our journey, we began to consider how frontline sales managers would actually manage their salespeople using the processes and metrics our research revealed. As we asserted earlier, a sales manager’s role is incredibly diverse, so there are probably countless ways that the concepts in this book could affect them. However, we chose to shine a light on what we believe is the most high-impact part of a manager’s job—conducting purposeful conversations with her sales reps.

Recalling that each selling role must employ a sales process that’s relevant to its unique Sales Activities, we chose to examine the management task by sales process. It became apparent that the nature of these manager-seller conversations should vary depending on the particular process that the manager is trying to manage. For example, if your reps engage primarily in Call Management activities, then you will integrate your A-O-R metrics into the context of their call planning. But if other reps engage in Account Management activities, then you’ll incorporate those metrics into a more strategic account planning session. Each process is distinct from the other, and the manner in which you use metrics to influence your salespeople’s behaviors will differ accordingly.

We also discovered that certain sales processes are capable of influencing certain Sales Objectives. For instance, a Territory Management process is perfectly suited to help you influence an Objective like Customer Focus, but it’s useless in affecting measures of Sales Force Capability. And while Opportunity Management activities are great for increasing Sales Force Capability, they will not make an impact on your Market Coverage. Therefore, depending on which Sales Objectives you are trying to achieve, you must manage toward them by directing a relevant sales process. Trying to achieve a Sales Objective by managing the wrong process will be a frustrating waste of effort.

Finally, we discussed the practicality of allowing the field sellers to select their own A-O-R metrics. A theme of this book is that leadership can gain more control over sales performance by providing clear guidance on the Activities, Objectives, and Results that it expects. However, there are sales forces for which variability in local demographics makes uniform management a suboptimal approach. In situations like this, it’s perfectly acceptable to let frontline managers customize their salespeople’s metrics, but you must make certain that your managers are skilled enough with the A-O-R framework to keep all of their sellers pointed toward the organization’s overall goals. Otherwise, the sales force will degenerate from a focused strategic weapon into a collection of individuals executing their own go-to-market strategies, which is probably not what you want.