CHAPTER 4

Our Brains on Story

We make sense of the events of our lives through stories.

—Daniel J. Siegel, M.D., author of Mindsight

The Barriers

We tend to put up barriers to people trying to influence us, and for good reason. It’s a natural defense mechanism. We do it to protect ourselves.

At the start of our Story Leaders workshops, we ask participants—usually a group of salespeople—to name the professions they trust the least. “Politicians!” is almost always the first answer, usually followed by “Salespeople!” And then, like clockwork, everyone in the room starts to laugh.

As salespeople, we know how difficult it is to build trust. Most of us have had bad experiences with salespeople ourselves. We know the uncomfortable feeling of being “sold to,” the feeling of someone trying to use us for their own financial gain.

Once the laughter dies down, we ask, “Why?” Why do people have negative stereotypes about salespeople and politicians? We hear the same answers again and again: “Because they’re manipulative.” “Because they’re in it only for themselves.” “Because they try to get me to do what they want me to do.” “Because they’re slimy and dishonest.”

Then we ask participants how they arrived at these perceptions. The obvious answer is past experience: all of the politicians we’ve seen embroiled in scandal, double-talking, reneging on campaign promises; all of the salespeople who’ve ever tried to sell us.

It’s a harsh reality for those of us in sales. Getting people to believe in us is difficult enough. Getting people to change when they’re predisposed to distrust us is even harder.

Reactive or Receptive?

Imagine walking into an electronics store to buy a DVD player. You’ve done a little homework and you more or less know what you want. Within 10 seconds, before you even find your aisle, a salesperson approaches and asks, “Can I help you, ma’am?”

Your automatic reply? “No, thanks, I’m just looking.”

It’s the kind of answer we give even when we’re not just looking, even when we could use a little help. It’s a natural defense against someone trying to influence us.

The reason for this automatic reply is revealed in the science of the mind. When our limbic area senses a threat, it sends a message to the reactive brain: “What do I need to do to be safe?” When the threat is great enough, we either go to fight or flight. At that point, our most primitive brain, the survival brain, kicks in and takes control.

For lesser threats, the message is processed by the side of the neocortex that reacts to danger: the left brain. The left brain can analyze the threat and determine how to deal with it. When we as sellers approach buyers, we are, by definition, activating the reactive side of their brains. When we lead with messages that make people feel like they’re being “sold to” or that simply threaten their paradigms or dogmas, the reactive mind instinctually kicks into gear.

Think of the last time you had a heated political debate with someone. Can you recall the unpleasant visceral reaction of having your deeply held beliefs challenged? And it’s not just contrary ideas that trigger your left brain. New ideas in general are met with resistance because we perceive them as trying to influence us to change.

But what if sellers could activate the right side of the brain, the receptive side?

The right side of the neocortex is responsible for the kinds of responses we want to trigger in others: “This feels good.” “I am safe.” “I am open to this.” “I want to hear more.” “This person [or idea] is not a threat to me.”

Mike’s Story: Sales Associate

I spent my first three years at Xerox Computer Services working in customer support. When my manager asked me to go into sales, I said no. He finally convinced me to do so, but only under one condition: I could keep my help-desk base salary, and if after six months I wanted to go back to the help desk, he would save a spot for me. I was given new business cards that said “sales associate.” Right away, buyers started reacting differently to me. They seemed wary. It dawned on me that my new title was part of the problem. After a couple of weeks, I went back to my old business cards, the ones that said “customer support.” Sure enough, buyers started treating me like they used to. I was back to being someone who was there to help them, not sell them.

Ben’s Story: A Good Story Is the Antidote

Not long ago, I was in New York leading a Story Leaders workshop for Oracle. After one of the sessions, a salesperson and workshop student, Nic, invited me to the second annual Oracle Financial Services Forum, an event geared toward Wall Street CIOs. Oracle’s president, Mark Hurd, was giving a breakfast keynote speech on the future of IT in financial services, particularly mobile technologies. About 80 executives were seated at tables on the main floor of the auditorium. More people filled the balcony, including many vendors and Oracle employees who wanted to hear what their president had to say.

All eyes turned to Mark when he arrived. After a few greetings, he strode to the podium, took his place behind the lectern, directed his assistant to load his PowerPoint presentation, and began discussing slides—slide after slide after slide.

After just a few minutes of Mark talking about Oracle’s position in the marketplace, Oracle’s mobility offerings, and so forth, Nic asked me to look across the room. I realized that almost no one was looking at Mark. The CIOs had their BlackBerrys and iPhones out, checking e-mail, eating breakfast, and so on. Nic and I were amazed. Here was Mark, the president of one of the world’s largest companies, a man with a commanding presence, and hardly anyone in the room was giving him their full attention. It was almost as if Mark weren’t even there.

Just then, Mark looked up from his slides and said, “A couple of weeks ago, I was in the car with my daughter, driving to the San Francisco airport, trying to check the status of my flight on my cell phone. I couldn’t find it, and I was running out of patience. So my daughter says, ‘Just relax, Dad.’ Then she got out her iPhone and had the information I needed in about 30 seconds.”

The story was short, personal, and to the point. Mark was saying that mobile devices are the future of communication because they’ve already been embraced by younger generations. But it wasn’t the point of his story that got me so much as the effect of it. The moment he began, everyone in the room, without exception, turned their attention to Mark. The CIOs set aside their BlackBerrys, put down their knives and forks, and listened. And even when Mark returned to his slides, the audience stayed engaged, right through to the end of his presentation. People asked questions and took notes, and one of the CIOs even told a similar story about his teenaged daughter.

Once Upon a Time

What happened during Mark Hurd’s speech was no surprise. Our minds are wired to respond to a story. It’s intrinsic to who we are and how our brains function. As humans, we are natural story learners, storytellers, and story listeners.

Ever notice how the words once upon a time can calm a child? At bedtime, they’re like magic. The child instantly relaxes. And the next night, without fail, the child asks, “Can you tell me another story?”

Stories have a similarly soothing effect on adults. When we hear “once upon a time” or “Can I tell you a story?” we nonconsciously tell ourselves, “Oh, it’s just a story. I don’t have to do anything or decide anything. I can just listen and enjoy.” But at the same time we relax, we also focus and pay attention, because we are story learners, biologically wired to survive by learning through narrative. Our nonconscious mind is saying, “It’s just a story,” but it’s also saying, “I’d better pay attention, I might learn something.” This is the power of a story.

Facts, figures, lists, and statistics require us to do heavy mental lifting—left-brain work. Give the left brain some information, and it will immediately want details. Give the left brain those details, and it will immediately want more information. The left brain is constantly fighting to find answers. It has a low tolerance for gray areas. But give the left brain too much information—say, too many slides—and you might lose a listener’s interest altogether.

By contrast, the right brain sees the big picture; it thinks in images, pictures, and stories. For this reason, story is an antidote to the critical left brain, offering a pathway around the barriers that we put up against people trying to influence us. Stories activate our limbic brain—our emotional center—because they contain the language of emotion. They also activate our sensory perception system, where all of our senses are kinesthetically connected. We experience a story in sensory terms in our imagination—we see it, we hear it, we smell it, we taste it, and we feel it.

We know from brain research that stories activate the right brain, but we also know it from experience. Simply put, stories feel good. On a visceral level, we are inclined to feel engaged with someone the moment that person says, “Hey, that reminds me of something that happened yesterday . . .”

Deciding to change isn’t simply about logic, however much we’d like to believe so. It would be more accurate to say that we make decisions based on feelings, and then we use logic after the fact to justify our decisions. In relaxing the left brain and opening up the emotional right brain, stories cater to the part of the brain that decides to trust, to act—the part that says, “I’m going to change.”

Can you imagine a better frame of mind to cultivate in a buyer? Making the decision to listen to someone, to change, or to buy is ultimately a right-brain activity. Stories just feel good to people. Since Mike and I started asking our customers, “Can I tell you a story?” neither of us has been turned down yet.

95,000 Years of Storytelling

Back when we first started teaching Story Leaders, we were talking about the power of story with Derek, an anthropologist friend of ours. Derek told us about a recent family vacation to Australia. While he was there, everyone, including his tour guide, kept telling him, “You have to take your family to Ayers Rock.” Ayers Rock, known as Uluru to the aboriginal people, is a massive sandstone formation. Australia’s most famous natural landmark, it is a sacred site to the Aborigines. Derek wanted to go, but Uluru is in the middle of a vast desert in the center of the continent, and it was midsummer, a blazing 105 degrees. The desert hardly seemed like a good destination for a family with young kids.

The anthropologist in Derek couldn’t resist, though. After driving across the desert for several hours, he and his family were rewarded with a stunning sight, an island of sandstone rising more than 1,100 feet from the barren desert floor, with a circumference of almost six miles. But the exterior of Uluru wasn’t what amazed them most. Inside the mountain are rooms. Aboriginal settlers used the rock as their home base more than 10,000 years ago. On the walls of these rooms are paintings that tell stories of danger, survival, medicine, the seasons, hunting, spices, and so on. In essence, these were classrooms, where aboriginal culture was passed down through the generations by way of visual stories—stories that are still there one hundred centuries later.

Derek told us that stories have been the primary means of conveying ideas since humans developed language some 95,000 years ago. They appear not only at Uluru but in the remnants of all ancient civilizations, including the Egyptian pyramids and Mayan ruins. As long as we’ve been communicating with each other, we’ve been telling stories, one way or another. As a species, we evolved as storytellers.

Brad Kerr’s Story: A Family Tradition

I attended a Story Leaders workshop in August 2010. As the sales director of a large IT company, I was eager to improve my own sales effectiveness. At the same time, I was pretty skeptical. I got what Mike and Ben were saying about vulnerability and empathy and all that, but I didn’t think it would fly at my company. It took my three-year-old son and five-year-old daughter to change my mind.

My first night home after the workshop, I sat down to dinner with my family and started asking my kids the usual questions: “What did you do today?” “Who did you play with?” “Did you have fun at school?” My son, Jack, was already too busy with his meatloaf to answer, and my daughter, Natalie, gave me the usual one-word replies: “Play.” “Lauren.” “Yes.” Then we proceeded to eat in silence. It wasn’t the first time I’d been disappointed that my kids wouldn’t open up more. But this time, listening to the scrape of their forks, I thought back to the workshop and realized what the problem was: questions! I was doing no better with my kids than a salesman who interrogates his customers.

So I tried something new. I said, “Anybody want to hear a story?”

Immediately, Jack and Natalie looked up from their dinner. “Yes.”

So I told them about my week in San Diego—meeting new people, going to dinner with my boss. It wasn’t the most exciting story, but I remembered what I’d learned in the workshop and showed some vulnerability. “Daddy wasn’t the best golf player,” I said. And then I passed the torch. “So Natalie, what’s been going on with you?”

Without missing a beat, she started telling me about school, how they were farming ants and how she and Lauren had played princesses on the playground while the boys were playing policeman. I couldn’t believe how forthcoming she was. Then Jack jumped in with a story too. My wife shot me a look of disbelief. All I could do was smile.

Storytelling at dinner is a family tradition now. As soon as we sit down, one of the kids will say, “Raise your hand if you have a story.” And we all raise our hands. Jack prides himself on telling the longest stories and will warn us beforehand: “This is going to be a long one!” Natalie loves to hear stories about Mommy and Daddy when we were kids. And my wife and I love hearing and telling stories, too. As I write this, I’m thinking about dinner tonight, when I’ll tell them the story of how their story will be shared in a book forever.

Ben’s Story: Zoe’s History Lesson, Part Two

Remember the story of Zoe and her disdain for history, which I told in the Introduction? I’m happy to report that the problem didn’t last. The next semester, Zoe’s class studied Greek mythology, and this time the teacher didn’t use a PowerPoint presentation on the Smart Board. Instead, she broke the class into groups and gave them a two-month assignment to study one of the myths and then perform it as a play for the rest of the class. The play was the final exam. Zoe got an A. Given the chance to learn through a story, she turned the corner in history class.

Story Learners

Dr. Jerome Bruner, one of the fathers of cognitive psychology, studied the profound effects of story on children. He observed that as early as the age of two, we are thinking and communicating in story. His research showed that babies organize their ideas in story, everything from “not more” to “I want.” In the 1980s, his hypothesis led to a larger study that monitored and recorded the pre-language sounds of babies alone in their cribs. A group of linguists and psychologists at Harvard concluded that the sounds constituted attempts at storytelling. The findings ended up in a book, Narratives from the Crib.

In other words, even before we learn language, we use narrative to organize our thoughts and ideas. We think in story. We learn through story. By the time we’re in school, most of us have heard thousands of them—fables, fairy tales, myths, lessons passed down to us from our parents, and so on. And because we’re story learners, they tend to stick with us.

Ben’s Story: The Boy Who Cried Wolf

A couple of years ago, I was in the backyard with my youngest daughter, Abby, when my wife came out and asked if I could help her do some work in the house.

“I’d be happy to,” I said, “but I can’t. My shoulder hurts.”

Abby had the presence of mind to wait until my wife was back inside before she turned to me with a disapproving look. “Dad,” she said, “remember the boy who cried wolf?”

Abby was six years old. It had probably been a year since I’d told her about the boy who cried wolf, but the story—and its lesson—had stuck with her. All I could do was put a finger to my lips and say, “Ssshhh.”

Stages of the Storytelling Process

In George W. Bush’s memoir, Decision Points, the ex-president relates a story about meeting with former Russian president Vladimir Putin. Early in the meeting, Putin was stiff and formal, mainly reading from prepared note cards. Exasperated, President Bush interrupted with a question: “Is it true your mother gave you a cross that you had blessed in Jerusalem?” The question prompted Putin to tell the story of how he almost lost the cross in a house fire, but firemen were able to retrieve it. “I felt the tension drain from the meeting room,” writes Bush, recounting the moment. He then goes on to detail how he and Putin drew closer as Putin was telling the story and how, afterward, they remained more connected. (“I was able to get a sense of his soul,” Bush famously said later. Given their subsequent difficulties, whether Putin “sold” Bush using story remains open to speculation.)

University of North Carolina professor Brian Sturm, who teaches storytelling and folklore, explains that the storytelling process works in seven distinct stages. His model reveals the effects of story on both the listener and teller.

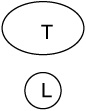

Stage 1

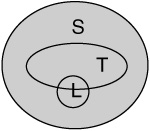

The teller (T) and the listener (L) are engaged in conversation, an “active mode of consciousness.” They are separate and may even be in opposition to or in competition with each other (see Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1 Storytelling Process, Stage 1

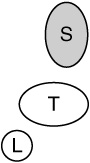

Stage 2

The teller initiates a story (S) with some variation of “once upon a time” or “Can I tell you a story?” The story, as it begins, becomes a third entity in the relationship between the teller and listener (see Figure 4.2).

Figure 4.2 Storytelling Process, Stage 2

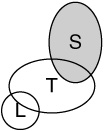

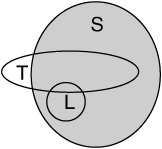

Stage 3

The teller becomes involved. As the story proceeds, the teller gets caught up in the story, reliving or at least reflecting on what is happening in it. At this stage, the listener begins to feel more connected with the teller, because the teller is no longer in opposition or competition but is instead involved in the story (see Figure 4.3).

Figure 4.3 Storytelling Process, Stage 3

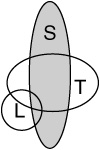

Stage 4

The listener becomes involved in the story. As the story proceeds, the listener begins to relive or reflect on what is happening in the story. The listener and teller begin to share the experience (see Figure 4.4).

Figure 4.4 Storytelling Process, Stage 4

Stage 5

As the story becomes more compelling, the listener and teller become part of the story and therefore more closely connected. Note that both the teller and listener are “inside” the story; the story is bigger than either of them. The story is now the communicating entity, more so than the teller. The teller and listener are equals inside the story experience. Both are in the “story realm,” a passive mode of consciousness or even an altered state of consciousness (see Figure 4.5).

Figure 4.5 Storytelling Process, Stage 5

Stage 6

The teller begins to wrap up the story and withdraw from the story realm (see Figure 4.6).

Figure 4.6 Storytelling Process, Stage 6

Stage 7

All stories have to end. The story is over but still remembered, leaving the listener and teller still connected, in a way that they weren’t connected before the story began (see Figure 4.7).

Figure 4.7 Storytelling Process, Stage 7

Needless to say, this process plays itself out with greater or lesser effectiveness depending upon the storytelling skills of the teller, the listening skills of the listener, and the quality of the story itself. However, it is not at all uncommon for people to be greatly moved or greatly influenced by stories that they hear from strangers. A perfect example of this (in written form) is the bestselling Chicken Soup series of books, which contain collections of personal stories.