INTRODUCTION

Ben’s Story: Zoe’s History Lesson

Before we get into what great salespeople do, I’d like to share a story about my daughter Zoe, one that brought new meaning to the work Mike and I are doing.

Last January, my wife and I attended a midyear parent-teacher conference. Zoe was in sixth grade, and we were expecting the usual—a glowing report. But this meeting was different. I could tell there was a problem from the moment we sat down with Zoe’s teacher.

“Zoe is struggling in history,” she said. She explained that Zoe’s test scores had dropped. Maybe it was Zoe’s comprehension, or maybe it was her recall—the teacher couldn’t be sure. The news hit me like a punch in the stomach. Something was wrong with my little girl, and the teacher couldn’t even tell me what it was. On top of that, I’d always loved history, and I wanted it to be a subject my kids loved, too.

That night, I asked Zoe about history. She said she hated having to remember stupid names, dates, and facts. “Why do I need to know what happened to a bunch of old men 200 years ago?” she asked.

They’d just finished studying colonial American history, so I asked her what she’d learned about the Revolution.

“They signed the Declaration of Independence,” she said.

“What did that mean?”

“I don’t remember,” she said.

Over the next few weeks, I asked some of Zoe’s friends about history, and they all felt the same way she did. I just didn’t get it. I remembered history lessons as being full of exciting stories about interesting people. To this day, I still remember learning about Paul Revere in grade school.

Paul was born to a French immigrant father who came to the new colonies when he was 13. Paul’s mother was a New England socialite from an established Boston area family. As a young boy, Paul loved working as an apprentice to his father, a silversmith. His dad was known as the best engraver around, and Paul wanted to be just like him. He instilled in Paul an entrepreneurial ethic: “Make something of yourself.”

Paul also greatly admired his mother and her community activism. The family went to church every Sunday and discussed politics, business, and religion at dinner every night. No subject was out of bounds. Paul soon began to form his own views on important subjects of the day, particularly the Church of England.

When Paul was 17, his father died. Paul was doubly crushed. He wanted to take over the silversmith business, but according to English law, he was too young. With few options, he enlisted in the Provincial Army to fight in the French and Indian War. During the war, Paul experienced tyranny and oppression firsthand. He emerged from the army an independent thinker who was not afraid to challenge the status quo and fight for what he believed was right.

Because I connected with Paul’s story, I never had any trouble understanding and remembering the related historic events: the Boston Tea Party, the colonies voting to reject British rule and adopt the Declaration of Independence, the “shot heard around the world,” and of course Paul’s famous ride (“The British are coming, the British are coming!”). But when I tried telling Zoe the story, hoping to spark her interest, she just gave me a funny look.

“Dad,” she said, “that’s not how we learn history.”

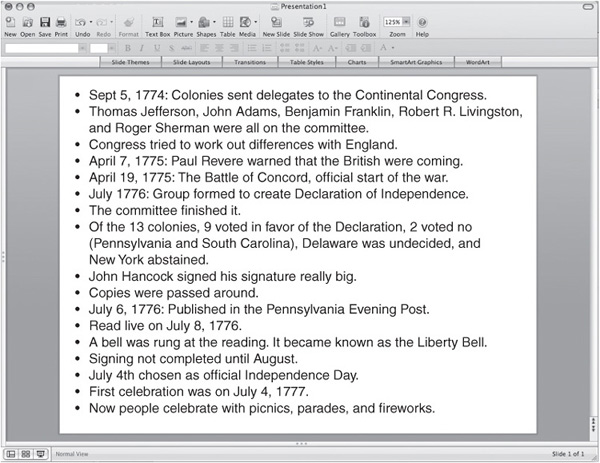

That’s when I remembered seeing the new Smart Board in her classroom during the parent-teacher conference. Smart Boards are “interactive whiteboards” that have begun replacing traditional chalkboards in a lot of American classrooms, and all of the classes in Zoe’s school had gotten them at the beginning of the year. Among other things, Smart Boards allow teachers to present their lessons in the form of PowerPoint presentations. Figure I.1 on the following page shows the PowerPoint slide Zoe’s teacher used in her lesson about the Declaration of Independence.

You can see the difference between the ways Zoe and I learned history: All she got was what happened. I got the what and the why. Of course, Zoe isn’t the only student to suffer this sort of “teaching,” and the problem isn’t confined to our educational system. The same thing is happening every day in corporate America. We try to educate our salespeople by burying them in an avalanche of facts and figures. Then they go out into the field and do the same thing to customers. It’s little surprise so few of those customers buy in. They don’t like it any more than Zoe did.

Figure I.1 The PowerPoint Slide Zoe’s Teacher Used in Her Lesson About the Declaration of Independence

Why Did We Write This Book?

We set out to demystify what great salespeople do.

We began this journey primarily for ourselves, to improve how we sell. Sales is the only career the two of us have ever known. And we wrote this book to share what we’ve discovered along this journey—how we can all better influence change in the world.

Here’s what we have always known about selling:

People decide who to buy from as much as what to buy.

People prefer to do business with people like themselves.

Selling is a social endeavor involving interpersonal relationships.

A person’s effectiveness as a communicator has a direct impact on his or her effectiveness selling.

The best salespeople communicate in a way that gets people to share information about themselves; fosters openness to new ideas; and inspires others to take action (i.e., to buy).

What we didn’t know was what makes the best salespeople such effective communicators. Was it personality, intelligence, persistence, experience, background, or just plain luck? Was it an inherent gift, or could it be learned and taught?

We’ve been training salespeople for a combined 40 years. For most of that time, our definition of selling has been some variation of “helping people solve problems.” The definition was based on the belief that the decision to “buy” is like problem solving, logical and rational.

At the time we got into the sales enablement industry, empirical industry research had established that what distinguished successful sellers from less successful ones was questions: the best sellers asked their customers questions. Lots of questions. So for our Solution Selling and CustomerCentric Selling workshops, we taught salespeople to ask buyers a series of logic-oriented questions designed to lead the buyer to conclude the seller’s product was the logical, right answer.

As it turns out, a lot of our basic assumptions were wrong. People are not logical and rational when making the decision to buy. Furthermore, asking buyers questions—at least the kinds of questions we were training salespeople to ask— is not an effective means of connection or persuasion. In fact, the way we conditioned salespeople to ask questions has proven to be often counterproductive.

It also turns out that a lot of the early sales industry research had misinterpreted what the most influential salespeople were actually doing. They weren’t just asking buyers questions; they were establishing emotional connections, building what we used to call “rapport.” They were doing things that weren’t being taught in our training or anyone else’s.

In the introduction to his bestselling book Solution Selling (1994), Mike wrote, “Superior sellers (I call them Eagles) have intuitive relationship building skills; they empathically listen, they establish sincerity early in the sales call, and they establish a high level of confidence with their buyer.” These skills—relationship building, empathic listening, and so forth—were not addressed any further in the book because, frankly, we didn’t know what else to say about it. To our knowledge, they weren’t teachable skills. Either you had the gift or you didn’t.

Nearly two decades after the publication of Solution Selling, the sales profession hasn’t changed much. Other professions have evolved and moved forward, but we’re still doing things the same way we did 20 years ago, and it’s still not working.

When we first began training salespeople, we used to talk about the “80/20 rule”: in most companies, 20 percent of the salespeople brought in 80 percent of the business, while the other 80 percent of salespeople fought over the scraps. Only a few salespeople were able to develop mutual trust and respect with customers. Only a few were able to reach the high level of connection that fosters collaboration, the reciprocal sharing of ideas and beliefs that can move people to change.

If the prevailing sales models worked, you’d expect a shift away from the 80/20 rule over the years as more sellers improved and took a bigger slice of the pie. In fact, it’s gotten worse. Recent research shows that the gap between the best sellers and the rest of the pack has actually widened. This is an especially hard pill for us to swallow, because we’re the ones who created the paradigm.

So why aren’t we as a profession getting better at what we do? What’s holding us back? And why haven’t we been pursuing these questions more aggressively? It’s ironic: somewhere along the line, a profession whose prevailing model is based on questions stopped asking questions about itself.

So we did it. We began challenging our own beliefs, starting with, “Is there a better way?” This led to more and more questions, a domino effect, and soon we found ourselves in fields of study that had been previously off limits to us—fields that explored the mysteries of communication that we’d written off as unteachable because they fell outside the purview of our models and industry research.

What we soon learned was that we should have been looking for answers outside the sales productivity industry all along. People in other disciplines already understood a lot more about sales than professional salespeople did. Our research led us to an entirely new definition of selling. Selling isn’t about “solving problems” or “providing solutions.” Selling is influencing change—influencing people to change. This definition is based on a greater understanding of how we decide to trust some people and not others, how we decide to take a leap of faith and try something new, how we decide to buy or not to buy.

In this book, we share our stories and our findings, drawing on our decades of personal selling experience and synthesizing research from a wide range of disciplines including neuroscience, psychology, sociology, anthropology, and others. We pull it all together into a field-tested framework developed in our Story Leaders workshops. It’s a book for sales professionals and for anyone else—executives, politicians, teachers, attorneys, consultants, parents, and so on—whose work involves influencing others, whether you’re “selling” products, services, ideas, advice, or beliefs.

By demystifying what great salespeople do, we believe we ourselves have learned to better influence change, develop deeper relationships with our customers, and find greater meaning in selling.