CHAPTER 2

Earth Is No Longer the Center of the Universe

There is only one thing more powerful than all the armies in the world; that is an idea whose time has come.

—Victor Hugo

The Geocentric Model

Understanding how we decide to act is really a story of technology. Technology changes paradigms. People once believed Earth was the center of the universe and all other objects orbited around it. Aristotle’s geocentric model served as the predominant cosmological paradigm into the sixteenth century.

There were many good reasons to believe all heavenly bodies circled our planet. The geocentric model was “state of the art” for its time. Astrological observations suggested that the stars, our sun, and all known planets revolved around Earth each day, making Earth the center of that system. The second common notion supporting the geocentric model was that Earth does not seem to move. To an earth-bound observer, our planet appears grounded, solid, stable. What better hypothesis could anyone have come up with, other than Earth was the center of the universe? There was no other explanation.

The first big challenge to the geocentric model came along in the sixteenth century. With the advent of the telescope, Copernicus observed new phenomena, such as instances of moons orbiting other planets. To the majority of people at the time, however, the evidence was not strong enough to change their beliefs.

In 1609, further advancements in technology enabled Galileo to seriously challenge the geocentric paradigm. He was able to see the moons of Jupiter orbiting the planet. However, the evidence was still not great enough to change most people’s minds. It took one more year before the tipping point arrived. In that one defining year, as technological advances further improved the telescope, Galileo was able to observe additional planets in orbit around a greater body, just as he had observed with the moons of Jupiter. This was enough evidence to finally dispel the prevailing state-of-the-art model. Through disruptive technology, the world’s leading cosmological paradigm was turned on its head: Earth was no longer the center of the universe.

Logic Is No Longer the Center of the Sales Universe

Since ancient civilizations, people have been attempting to understand how our minds work and how we decide to act. Aristotle declared that reason, logic, and rational thought are at the center of our decision-making processes. He believed that emotion wreaks havoc on our otherwise logical behavior. Other influential thinkers ascribed a more significant role to emotion, but they lacked the technological tools to substantiate their theories. As a result, the realm of emotion, intuition, and “gut feel” went unexplained for centuries. Meanwhile, the paradigm of logic and reason became the basis for the study of influence and persuasion and found its way into twentieth-and early twenty-first-century paradigms of selling.

Just as Aristotle lacked a telescope that could reveal the true nature of the universe, he lacked a “telescope” into the brain that could reveal the true nature of human behavior. Even during most of the twentieth century, the brain was largely a mystery. Since the mid-1990s, however, advances in technology have given scientists the capability to monitor brain processes in real time. With the advent of technologies such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), brain scanning, and other digital brain imaging technologies, a new era has emerged in the neurosciences.

Recent observations have completely reshaped our beliefs about what motivates us to act and how we make decisions (e.g., when and how to change and whom to trust) and respond to stimuli. It’s a classic case of disruptive new technologies changing a paradigm. We now have a new understanding of influence, persuasion, and selling. We are reminded that Earth is not the center of the universe, and that logic and reason, it turns out, are not at the center of our decision-making processes.

Mike’s Story: The “Solution Sale”

When I was first asked to be a sales trainer in 1976 for Xerox Computer Services, my paradigm of selling was based primarily on logic and reason. I defined selling as the process of helping someone solve a problem using our products. At the time, I was the number-one salesperson in the company, and how I “solved someone’s problem” was the only way I could explain what differentiated me from the rest of the sales force. I agreed to move into the role of trainer because I saw it as a way to help others.

My paradigm of selling was also shaped by my work with behavioral researcher Neil Rackham in 1979. Revenue production at Xerox, as at most companies, was highly disproportionate, so Xerox hired Rackham to study what the top 20 percent of salespeople were doing so we could teach it to the mediocre masses. This study was called the SPIN project.

Rackham conducted the study by recording the behaviors of both buyers and sellers in 1,500 sales calls made by the top 20 percent of Xerox sellers. We focused on what was observable at the time, given the technology of the time: the types of questions those top sellers were asking.

After poring over the data, all of the people on the SPIN project team, including me, arrived at a linear, logic-oriented, questioning approach. The paradigm held that for a buyer to cooperate with a salesperson, the salesperson had to learn how to ask a series of questions that would lead the buyer to see that the seller’s offering was the solution to the buyer’s problem. The B2B sales training and productivity industry was born.

Many “variation on a theme” sales methodologies can be traced to the original methodologies—SPIN Selling, Solution Selling, Consultative Selling, CustomerCentric Selling, and so on—all of which were based on helping a buyer use reason and logic to solve a problem, and which include a logic-oriented “value proposition” in order to help a buyer justify a decision. Our global definition of selling was based on the belief that decision making was primarily linear, logical, and rational.

This paradigm discounted the value of emotional connection. At the time, we had no way of even articulating how any two individuals connected emotionally. I had a hunch that people made emotional decisions and then justified those decisions later using logic and value. A basic principle of my early training methodology, Solution Selling, stated: “People make emotional decisions for logical reasons.” However, none of us in the industry knew how to explain what an emotional decision really was, much less how to influence one on purpose. The best theory I could muster at the time was that the buyer would want to buy from the seller who created the best vision of using his or her product. Our paradigm of selling was based on the science of the time. We couldn’t look inside buyers’ and sellers’ hearts and minds; all we could do was study their external behaviors and draw our conclusions accordingly. That was the state of the art.

What we didn’t focus on during the SPIN project was how the top sellers connected with buyers before they started asking their questions. Back then, we used terms like “woo,” “mojo,” and “gift of gab.” However, we had no scientific evidence that something deliberate and replicable was happening. It was just “magic.” In fact, Xerox convinced me that emotional connection (what they called “rapport”) is the unique chemistry between two people, and no two combinations are the same. I took that as gospel and trusted it for years. I believe the rest of the industry did too. My gut still told me that people make emotional decisions and then support those decisions after the fact with logic. I just had no model to support my gut feeling, no evidence to prove it, so I just didn’t deal with it.

And so the old paradigm remained intact. We modeled what we could research and explain. It wasn’t until new technologies came along—technologies that allowed us to “see” inside the brain—that we finally had our own version of Galileo’s telescope, one that forced us to completely reevaluate our logic-based sales paradigm.

The New Science of the Brain

Technology over the past 15 years has seriously undermined our old understanding of decision making, persuasion, influence, and change. For the first time in history, neuroscientists are able to see into the source of what was previously unexplainable: how our minds actually work.

Breakthroughs in the field of neuroscience have revealed that our decisions are not solely based on logic—not even close. In fact, decision-making processes are much more complex and use a highly integrated system throughout our entire bodies. We are not the machines of reason and logic that we previously thought we were. As Richard Restak, author of several books about the brain, states, “We are not thinking machines, we are feeling machines that think.”

We have learned that it is important to better understand our internal systems: how we work, how we respond to outside stimuli, how we learn, how we recall experiences, and, ultimately, what activates what parts of our internal systems when we interact with others.

It’s useful to make a distinction between the brain and the mind. For simplicity, we will define the brain as “the organ of thought and neural coordination” and the mind as “the process that regulates the flow of energy and information throughout our bodies.”

A quick overview of this new understanding of the mind includes four aspects of the brain that are relevant to understanding how people change:

1. The three-part structure

2. Right and left hemispheres

3. Neuroplasticity

4. Mirror neurons

“But I’m a Salesperson, Not a Brain Scientist”

We promise not to get too sciencey. What follows is just a quick primer, some fundamental concepts about the brain that we’ll return to again and again in subsequent chapters. Once you grasp these basic concepts, you’ll begin to understand how and why people decide to change, how the brain goes from “here’s where I am today” to “here’s something new I want to try.” Possessing that knowledge will give you a major advantage as an influencer.

The Three-Part Structure

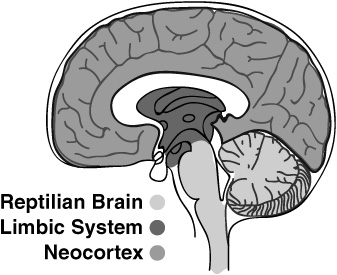

According to neuroscientist Paul D. MacLean, the brain developed in three stages (see Figure 2.1) over the course of human evolution, resulting in a “triune” structure (i.e., consisting of three parts). First came the reptilian (survival) brain, then the limbic (emotional) brain, then the neocortex (thinking) brain. Today, that’s the same order in which our brains develop in the womb.

Figure 2.1 The Evolution-Designed Brain

The reptilian (survival) brain is the most primitive brain structure, making up the part of the brain that originally dominated the forebrains of reptiles and birds. Every species with a central nervous system has this structure. The survival brain regulates basic survival functions such as breathing and blood flow as well as instinctual behaviors related to aggression, dominance, territoriality, ritual displays, and the “fight or flight” decision in response to danger. When you instinctively swerve to miss an oncoming car in your lane, that’s the highly evolved survival brain in action. You don’t stop to think, you don’t weigh the options, you don’t consider pros and cons—you react.

Approximately two hundred million years ago, when the first mammals appeared, the limbic (emotional) brain evolved. Surrounding the survival brain like a doughnut, the limbic system gave mammals a unique capability—to feel. The emotional brain is what separates mammals from other species and gives them the ability to evaluate their conditions: “Is this good or bad?” As such, it’s the primary part of the brain that motivates our actions (and even our reasoning and thought) and gives us the ability to learn, remember, adapt, and change. It’s the limbic brain that draws us to what feels good and repels us from what doesn’t. The limbic brain is believed to be responsible for motivation and emotion.

Like the limbic brain, the neocortex (thinking) brain is also found uniquely in mammals, but it is massively larger, proportionately, in humans than in other mammals. It’s what makes humans distinctly different from all other species. The newest and least evolved part of the brain, the neocortex forms the outer layer and confers the ability for language, abstraction, planning, perception, and the capacity to recombine facts to form ideas. In short, the neocortex gives humans the unique advantage of advanced thought. But with this newest part of the brain comes a disadvantage, too: we can think too much.

The Brain’s Operating System

Aristotle put forth the idea of “proportionality,” proclaiming that our emotions are in equal and direct proportion to our reason. It was a compelling idea for its time, but just as technology eventually showed us that Earth is not the center of the universe, technology has also revealed that reason and emotion are not equals at the center of our internal universe. In fact, our emotions drive our reason.

As author and success coach Tony Robbins told the audience during his presentation at the 2006 TED conference, “I believe that the invisible force of internal drive, activated, is the most important thing in the world. . . . I believe emotion is the force of life.”

Neuroscientists would concur. Thanks to new technologies, scientists have been able to map the brain’s neural pathways, the specific routes by which information travels inside our heads. One important fact they’ve learned is that information flows from the inside out—from the survival brain, to the emotional brain, to the thinking brain. Since the emotional brain gets information before the thinking brain, it is capable of functioning independently of the neocortex, subconsciously, without cognitive thought. This makes sense, in evolutionary terms, because the emotional brain was there long before the thinking brain.

In his seminal book Emotional Intelligence, Daniel Goleman describes the limbic (emotional) system as the brain’s first responder. All sensory information goes there first. The limbic system processes the information and sends its response to the thinking brain, which then produces its own response. The brain, therefore, produces an emotional response before it produces a cognitive one.

The limbic system is like the operating system on your computer. All of the rest of your “software”—your thinking brain—sits atop this operating system (figuratively and literally) and is dependent upon it. You might say that our emotions have a mind of their own. Our rationality relies on our emotions. We’re hard-wired to feel first, think second.

In cases where sensory information carries little or no emotional weight, the thinking brain can assume a dominant role. But in cases where strong emotions are involved, the limbic system plays the main role in our behavior. The more intense an emotion, the more dominant the limbic system’s response.

In the world of selling, the subject of emotional connection has always been considered off limits, too touchy-feely. No more. Now that we know emotion is what drives people to do what they do—what drives buyers to buy—it’s a subject we can’t afford not to focus on. Logic and reason, while still factors in a buyer’s decision, are more likely to figure in after the fact, as a means of justifying a decision driven by emotion.

Like Dating a StairMaster

In the opening scene of The Social Network, Harvard student and future Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg (played by Jesse Eisenberg) sits at a small table in a crowded bar with his girlfriend from Boston University, Erica (Rooney Mara). Zuckerberg is obsessed with getting into one of the exclusive Harvard final clubs. He gives Erica a highly detailed, highly logical explanation of why it’s so important for him to do so. And then he logically asserts that she should be grateful to be his girlfriend. He tells her that if he gets in, he’ll be taking her to events and gatherings, and she’ll be meeting people she wouldn’t normally meet.

“What is that supposed to mean?” she says.

“Wait. Settle down.”

“What is it supposed to mean?” Erica says. “I’m going back to my dorm.”

“Wait,” says Zuckerberg. “Is this real?”

“Yes.”

“Then I apologize.”

But Erica has had enough of his logical, calculating, insulting behavior. She keeps telling him she’s leaving to go study. He repeatedly tells her she doesn’t have to study.

“Why do you keep saying I don’t have to study?” she finally says, exasperated.

“Because you go to B.U.,” Zuckerberg says. “Want to get some food?”

“It’s exhausting,” she says. “Going out with you is like dating a StairMaster. I think we should just be friends.”

“I don’t want friends,” Zuckerberg says.

“I was just being polite,” Erica says. “I have no intention of being friends with you.” She takes a deep breath. “Look, you are probably going to be a very successful computer person. But you’re going to go through life thinking that girls don’t like you because you’re a nerd. And I want you to know from the bottom of my heart that that won’t be true. It’ll be because you’re an asshole.”

Right Brain, Left Brain

Zuckerberg, as he’s portrayed in the movie, functions on a purely intellectual level. He’s clearly brilliant, but his mind seems disconnected from his heart. He wants a girlfriend, but he’s incapable of establishing a real emotional connection with the girl sitting right across the table from him. He has all the right answers, but he can’t open his mouth without saying something insensitive. He has zero social cognition, zero empathy, zero relationship skills. He comes off as rude and cold.

But whereas Erica sees Zuckerberg’s behavior as a personal failing, a neuroscientist might see it as a matter of left brain versus right brain. (It’s time for a little more science.) The neocortex—the thinking brain—is separated into two halves, or hemispheres. The brain architectures, types of cells, types of neurotransmitters, and receptor subtypes are all distributed between the two hemispheres in a markedly asymmetric fashion. As a result, the two hemispheres perform different functions and are responsible for processing different kinds of information. Think of the two halves as parallel but different processors; they give the human brain the ability to process information more effectively and exponentially faster.

The left hemisphere is primarily concerned with linear reasoning functions of language such as grammar and word production; numerical computation (exact calculation, numerical comparison, estimation); and direct fact retrieval. The left brain is analytical, logical, and rational. It thinks in literal terms and loves to solve problems and label things. It’s the side of the brain that craves information. Give it some information, and it’ll want more information about the information it just got.

The right hemisphere, on the other hand, is said to be the creative and emotional side of the human brain. It is primarily concerned with the holistic reasoning functions of language such as intonation and emphasis; approximate calculations and estimations; as well as pragmatic and contextual understanding (i.e., “common sense”).* The right brain thinks in pictures, images, and metaphors. It has the capacity to visualize and conceptualize. Social cognition resides in the right brain as well. All autobiographical memories are stored on the right. “Our right hemisphere gives us a more direct sense of the whole body, our waves and tides of emotions, and the pictures of lived experience that make up our autobiographical memory,” writes Daniel Seigel in Mindsight. “The right brain is the seat of our emotional and social selves.” The right brain is also directly connected to the limbic system and to the central nervous system—to all of our senses. As Jill Bolte Tayler puts it in My Stroke of Insight, “We are all kinesthetically connected through our right sides.”

The left brain says “no” because it becomes paralyzed from too little or too much information. The right brain says “yes” because it can imagine the possibilities and use intuition to fill in gray areas. We make decisions primarily with our right brain. Think of the college you attended, the car you drive, the home you bought, the significant other you chose to spend your life with, the names of your children, the political party you favor. If these were all logical, left-brain decisions, all of us—or at least all of us in similar circumstances—would drive the same car, the one that gets us from point a to point b most affordably and efficiently. There would be one right car, the logical choice. We’d also belong to the same political party, live in the same neighborhood in the same kind of house, marry the same kinds of men or women, and have the same number of children with the same names. Because there would be one right answer.

Of course, we don’t live our lives by logic. Every day, we make subjective decisions based on intuition, emotion, and the experiential memory that resides on an autobiographical shelf of the right brain.

But as salespeople, we’ve been taught to help buyers make a decision using logic. We’ve been taught to help them solve problems. It’s little wonder that at some point in the buy cycle, buyers often get paralyzed and decide to maintain the status quo. Up until now, we haven’t been speaking to their right brains. We haven’t reached their emotional centers, the place where decisions are actually made. We’ve been selling like computers, not people. Can you imagine having Mark Zuckerberg sell to you?

What Kind of Brain Are You?

In our Story Leaders workshops, we train a lot of salespeople with engineering backgrounds, people whose job it is to sell to other engineers. And a lot of them tell us, “I’m a left-brainer.” Which is to say, their right brains are telling them they’re left brainers.

That you have to be one or the other is a myth. Research shows that while one side is dominant at any point in time, both the left and right hemispheres operate simultaneously, all the time, in all of us. Sometimes, however, as a result of understimulation or underdevelopment, one side can become disproportionately dominant. Such is the case with the Mark Zuckerberg character in The Social Network. He’s so left brain that he can barely connect with another human being. But the good news for the Zuckerbergs of the world is that they can change. Science has shown that, even in adults, the brain retains its plasticity.

Old Dogs Can Learn New Tricks

For a long time, everyone believed sales was a left-brain game. Today that view is being challenged more and more. In A Whole New Mind: Why Right-Brainers Will Rule the Future, Daniel Pink posits that the future of global business belongs not to the left-brainers but to people with highly developed right-brain skills.

But when we focus on right-brain skills in our workshops, senior sales executives are often skeptical. “You can’t teach an old dog new tricks,” they say. It’s an objection based on the belief that we lose the ability to learn as we get older. Thankfully, it’s also a myth.

Science has established that plasticity in the brain is a constant throughout our lives. “Plasticity” refers to the brain’s ability to change and grow by making new synaptic connections to form new thoughts and ideas. Experience is what drives these changes in the brain. In the past 10 years or so, scientists have come to understand that we are constantly shaping our brain structure with every new experience. While it’s true that this process occurs more rapidly in children, it nevertheless continues into adulthood.

It’s this simple: we have new experiences; the brain makes new connections; new memories are formed. The brain constantly changes, grows, learns. Even in the old dogs among us.

One key factor in this process is the emotional weight of our experiences. Memories are formed in the limbic area, the emotional brain. The stronger the emotion associated with an experience, the better we remember it. If you’re studying for a test, for instance, you’re far more likely to remember the material if you have an emotional reaction to it, if you feel something. In the long run, we tend to remember more clearly the way an experience made us feel rather than the facts and details associated with that experience.

Monkey See, Monkey Do

Human beings, it turns out, are genetically wired to be empathetic.

When we see someone smile, we are inclined to smile ourselves. When we see someone suffering, we are inclined to feel their pain. And we all know what happens when we see someone yawn.

In the past 20 years, neuroscientists have discovered a physical basis for empathy. The brain is made up of tens of billions of cells called “neurons,” a special cell that sends electrochemical signals to other neurons. Studies show that some of these neurons have mirroring behaviors. A “mirror neuron” is a neuron that fires both when an animal acts with intent and when the animal observes the same action being performed with intent by another. It essentially “mirrors” the behavior of the other, as though the observer itself were acting.

Intent is important because it arises from the brain’s emotional center. If you pick up a glass of water because you’re thirsty, you’re likely to trigger mirror neurons in your dinner partner’s brain. But if you act without intent—if you simply pick up the glass and put it down—you’re unlikely to trigger mirror neurons. For the same reason, a fake yawn is much less likely to be mirrored than a real one. The degree of intent (i.e., emotion) is also important. The stronger the observed intent, the stronger the mirroring. Watching a waiter perform the Heimlich maneuver on a choking restaurant patron will produce a much stronger mirroring effect than watching your coworker perform the Heimlich on a dummy in a training session.

Mirror neurons were discovered by scientists studying macaque monkeys in the early 1990s. The scientists implanted devices in the monkeys’ brains so they could observe neurons “lighting up.” When JoJo the monkey watched another monkey eat a banana, for instance, the same neurons fired in JoJo’s brain as when JoJo himself ate a banana. (Today, brain imaging devices allow scientists to make such observations noninvasively.)

Subsequently, mirror neurons have been discovered in humans as well. Their existence in humans essentially means that we have the power to be emotionally contagious. We can create a sense of well-being in others, just as we can create unhappiness or pain. As Mark Ghoulston writes in Just Listen: Discover the Secret to Getting Through to Absolutely Anyone, “We constantly mirror the world.”

Later in the book, we’ll discuss the important role that mirror neurons can play in sales, particularly with regard to storytelling and empathetic listening.

Solving a Problem Is Not the Answer

So ends our quick primer on recent developments in neuroscience.

Obviously, we’ve barely scratched the surface. For the purposes of this book, though, all you need to know are the three-part structure of the brain, the right and left hemispheres, plasticity, and mirror neurons. These are the key concepts that have reshaped our understanding of selling by demystifying how people decide to act and, by extension, how buyers decide to buy. All along we believed that the decision to buy was a linear, logical one when in fact it is primarily an emotional one, governed by the limbic system and the right brain. By knowing this, we have a greater insight into what great salespeople are doing. We know that attempting to “solve a buyer’s problem” isn’t the full story. In fact, it’s only a small part of the story.

The new discoveries in the sciences have shifted our paradigm of selling. Decision making is not a problem-solving process, so neither should be the business of selling. In the pages that follow, we present a new model of selling based on a new understanding of how people really decide to change.